In the 18th century, women were not supposed to discuss politics. Or write about them. But Mercy Otis Warren (1728-1814) defied those conventions to become the nation’s only woman to write a history of the American Revolution. Married to James Warren of Plymouth, Massachusetts, the mother of five sons, she never intended to become a political commentator. In summers she tended to her garden and wrote nature poetry at the Warrens’ cottage on the Eel River; in winters she entertained friends at the family’s larger home on Court Street.

Then, the unthinkable happened. In early September 1769, a messenger arrived on horseback announcing that her oldest brother James Otis, Jr. or “Jemmy” had been assaulted by British officers in Boston. The injuries to his head were serious; so deep, “you could lay a finger in it,” observed the horrified young barrister, John Adams.

After Mercy rushed to his side, Jemmy recovered but was sadly changed. No longer was he the brilliant attorney who challenged the British government’s oppressive writs of assistance in court and declared “taxation without representation” was illegal. Now, he was mentally unstable, unable to continue his campaign with the Sons of Liberty protest of British oppression.

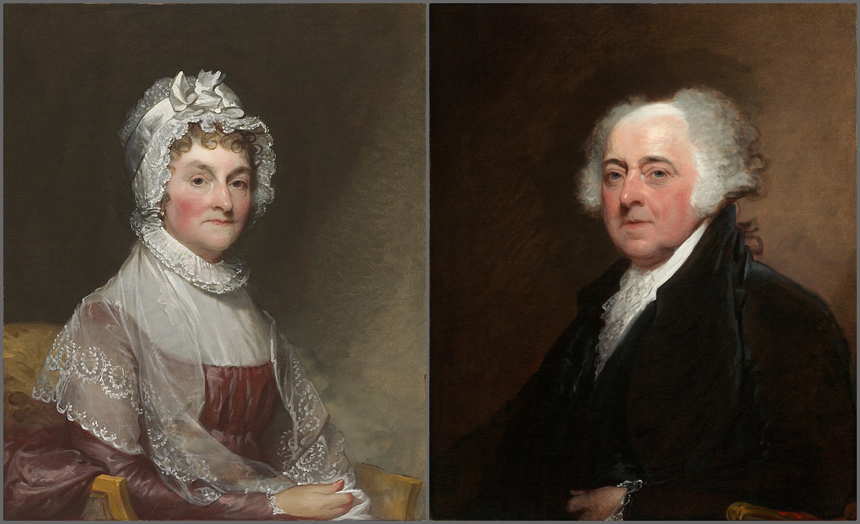

Meanwhile, correspondence from influential members of Parliament and other supportive Whigs piled up on Jemmy’s desk. The well-educated Mercy felt obliged to answer those letters, but even then did not plan to publicize her animosity in print. As a conventional colonial wife, she and her husband James were already hosting meetings for the Sons of Liberty at their Plymouth home while she sat listening in the chimney corner. But during those meetings their friend John Adams became so impressed with Mercy’s intelligence that he urged her to write for publication.

Initially she rejected his invitation until John’s wife, Abigail, persuaded her to write about the December 13, 1773, Boston Tea Party. The result was Mercy’s neo-classical poem, “The Squabble of the Sea Nymphs” or the Sacrifice of the Tuscaroroes. Following the publication of her poem, other events — including the British occupation of Boston, the closing of the harbor, and a recent discovery of Governor Thomas Hutchinson’s hostility towards the colony — inspired Mercy to write three satirical plays. The Adulateur in 1773 followed by The Defeat in 1774 were so popular that they were mentioned in the Boston Gazette, but because she was a woman her name did not appear. The third and most blistering of the plays was The Group, published in 1775. “I do not think it has sufficient merit for the public eye,” Mercy timidly confessed to James after showing him a draft. “Perhaps it might even be best to suppress it.”

She had good reason to be afraid, for the play skewered Hutchinson and the court-ordered councilors who had replaced locally elected officials. John Adams was so excited by the play that he rushed sections of it into publication in January 1775. By April 3, Boston’s patriotic printers Edes and Gil were advertising a full pamphlet edition. Sixteen days later the British attacked the patriots at Lexington and Concord.

Whatever effect Mercy’s writing had enlisting support for the Revolution was soon tempered by fears of safety for herself and her family. After James returned from his duties with the Provincial Congress, she rode with him to warn Rhode Island’s Sons of Liberty of the British attack, then packed up her sons and prepared to leave Plymouth. “I am still in a state of suspense Mercy wrote a friend, “[S]till uncertain whether I shall continue in my own pleasant habitation or whether in the few days I shall… seek a retreat in the wilderness.” Later, when the Provincial Congress moved its headquarters to Watertown, Mercy rode from Plymouth to Watertown where she served as James’s secretary and reported to John Adams about the course of the war. Impressed by her reportage, John urged her to write a history of the American Revolution.

Dutifully, Mercy made notes, interviewed patriots, and asked her friend Abigail for newspaper accounts. Since John was attending the Continental Congress in Philadelphia and James lived in Watertown, Mercy and Abigail consoled each other for living as independent wives and mothers.

On March 17, 1776, after 11,000 redcoats and Tories evacuated Boston, General George Washington asked James, then paymaster general of the Continental Army, to serve as the major general of Massachusetts and join the campaign as it moved south. James refused, claiming his health “could not support the fatigue” of active duty because he had just recovered from two illnesses. Privately, he had conceded to Mercy’s pleas to remain in Massachusetts. Active duty, his nervous wife insisted, would not only threaten his health but fill her with anguish. The mere thought of it was “a dagger in my bosom!” Consequently, he remained in the war-torn city of Boston and served as one of the directors of the Navy Board.

During her long separations from James, Mercy began writing her history. The challenge of the project, the death of friends, and the disruptions caused by the Revolution worried her so much that she suffered from “nervous headaches.” One of the disruptions was a smallpox epidemic, which led her, James, and Abigail to seek immunization.

Inoculation in the 1700s wasn’t as reliable or safe as it is today: A physician extracted pus from a victim of the disease and scratched it into an arm or leg of a well person. A milder form of the disease followed, after which most people survived and obtained lifetime immunity. While James and Abigail recovered, Mercy suffered for weeks from “faintings and langor.” Even after she was well, her eyesight was never the same, posing another obstacle to her completion of the history. But she continued her work in the 1770s and ’80s and past the end of the war.

The 1780s was a heady decade that saw a national craze for imported goods and clothes from England and the rise of social pretensions. These developments shocked the Warrens, as they contradicted the patriotic ideals of thrift, honesty, and brotherhood. In 1787, when a draft of the new Constitution was circulated to the states for ratification, Mercy consequently felt she had to protest. Her pamphlet, “Observations on the New Constitution, and on the Federal and State Conventions,” pleaded for the return of patriotic ideals and critiqued the Constitution for ignoring the rights of individuals and states.

Bylined as “A Columbia Patriot, Sic Transit Gloria Americana [Thus Passes American Glory],” Mercy’s pamphlet also faulted the rights of Congressional delegates to decide their salaries and that the Constitution neglected to mention rotation of political officers and important restrictions upon their terms of service. Moreover, the electoral college was “nearly tantamount to the exclusion of the voice of the people.” These and other lapses, Mercy insisted, could be included in a Bill of Rights. On February 6, 1788, when Massachusetts ratified the Constitution, many of her suggestions were anonymously attached to that document, which became the model for the Bill of Rights.

Across the ocean, British women writers were now publishing their works in their own names. Among them was social reformer Elizabeth Montagu and Mary Wollstonecraft, author of the feminist pamphlet “A Vindication of the Rights of Men.” In 1792, Mercy decided to use her byline for the first time in her collection, Poems, Dramatic and Miscellaneous.

By then her favorite son Winslow had died, her eyesight was failing, and the new Federalist policies of the government so distressed her that she lost interest in publishing her history. But at the turn of the 19th century, two events changed that. The first was the 1800 presidential election of Thomas Jefferson, who limited government spending and other federalist policies in favor of individual rights. The second was her oldest son James’s offer to serve as her secretary and prepare her history for publication.

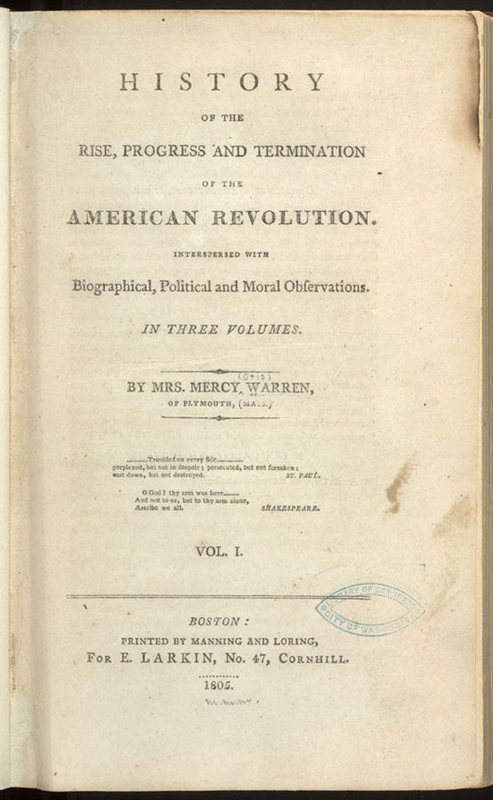

“Though in its infantile state, the young republic of America exhibits the happiest prospect,” septuagenarian Mercy declared on the last page of History of the Rise, Progress and Termination of the American Revolution. On December 21, 1805, she and James signed an agreement with Boston publisher Ebenezer Larkin to publish 1,500 copies of the book in three volumes. She sent copies to friends, former President John Adams, and President Thomas Jefferson, the last of whom ordered several for his cabinet. But after an initial flurry of congratulations, the book received little attention.

Especially disquieting was silence from her former mentor, John Adams. It was not until July 11, 1807, that the former president wrote Mercy that “in the spirit of friendship, that you may have an opportunity in the same spirit to correct” certain mistakes. Chief among his objections were Mercy’s words that “his prejudices and his passions were sometimes too strong for his sagacity and judgment.” Adams’s letter then continued to defend his deeds and accused Mercy of neglecting them. Stunned, she retorted that her history was “composed with impartiality, to state facts correctly and to draw characters with truth and candor.” After all, she added, quoting from John’s letter of March 1775, “the faithful historian delineates characters truly, let the censure fall where it will.”

A verbal duel commenced, one in which Mercy defended her book against her former mentor’s belief that she’d written a scathing analysis of his character. During that summer, Adams sent Mercy nine additional angry letters. Mercy replied with five letters of her own, assuring Adams that if she misrepresented him, she would correct them if there was a second edition. She then announced that she was ending their correspondence. “History is not the province of the ladies,” John later grumbled to his friend, Elbridge Gerry.

Five years later, John sent Mercy a note nostalgically recalling their early efforts to support a Revolution. Relieved that they were renewing their old friendship, she replied that she was especially “satisfied…to receive letters from a gentleman…with the same flow of esteem friendship and confidence which used to drop profusely from his pen.”

Those memories and her subsequent correspondence with John may have inspired Mercy to let history know about her work. On August 4, 1813, she asked John Adams to ride to the Boston Athenaeum and claim her ownership of her most important play, The Group. Two weeks later, John traveled to Boston and scrawled on that plagiarized copy in the Athenaeum, “This Play was written by Mercy Otis Warren,” and signed it as President John Adams.

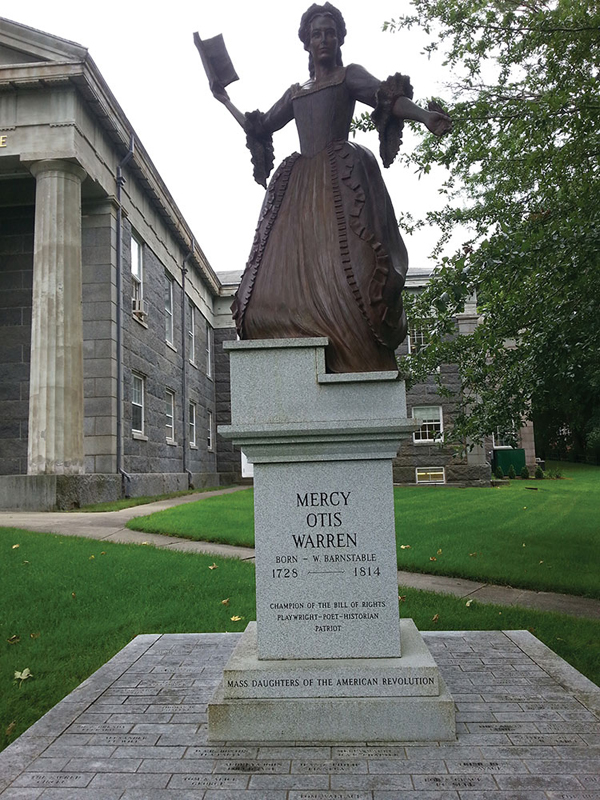

On October 19, 1814, Mercy Otis Warren died at age 86. Historians forgot about her for nearly 200 years, but recent feminist scholarship has established Warren as one of America’s most admirable Founding Mothers. Since 2001, her statue has stood at the front of the Barnstable, Massachusetts Superior Courthouse. A year later, the annual Mercy Otis Warren Award was established to honor a woman who has contributed outstanding volunteer service to Cape Cod. On March 1, 2024, The Mercy Otis Warren Society LLC was established in Plymouth to honor the town’s most remarkable Revolutionary-era woman.

“The people may again be reminded, that the elective franchise is in their own hands; that it ought not to be abused, either for personal gratification, of the indulgence of partisan acrimony,” Mercy wrote in her history. Two-hundred-ten years after her death, her words are as current today as they when first written; they seal her place in history as one of America’s most prescient Founding Mothers.

Nancy Rubin Stuart often writes about women and social history. She is the author of The Muse of the Revolution: The Secret Pen of Mercy Otis Warren and the Founding of a Nation. Visit nancyrubinstuart.com

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

She really was a wonderful woman indeed, Nancy. One that overcame monumental hardships mentally, emotionally, psychologically, socially and physically. Her endurance and perseverance with all of these obstacles is nothing short of astounding.

The fact Mercy lived until almost age 86 over 200 years ago is very unusual in itself (woman or man), much less with all she had to go through. Her suffering from nervous headaches is very understandable, and there wasn’t much that could be done back then.

I’m glad she was immunized from smallpox but her eyesight was diminished afterwards which was so critical. Honestly though, she may have died prematurely without having had it. I’d like to read one of her books, too. The 18th century style and some words might throw me off a bit here and there, but not enough not to understand it. I love that century’s speaking style (and the 19th), so it will be a labor of love to read what she had to say directly. The statue of Mercy at the bottom is very beautiful, regal and commanding. It really captures her essence.

I’d love to find a book by this wonderful woman. Great story!!