The Saturday Evening Post knows a thing or two about documenting big events across the decades. This magazine reported on the Civil War and the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad. It’s documented historical milemarkers like emancipation, suffrage, and Obergefell v. Hodges. And each time the calendar turns, we, like all of you, wonder what will be the next era-defining event will be. With that in mind, here’s a look at the events that have defined each decade in the United States since 1900. Here in part 1, we start with the first three decades of the 1900s.

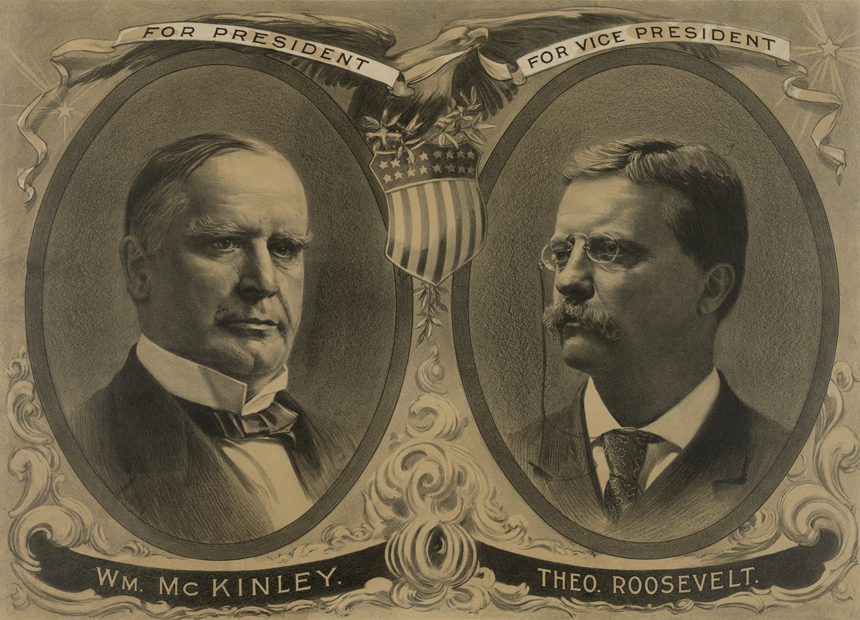

1900s: McKinley Assassinated; Teddy Roosevelt Becomes President

The assassinations of Presidents Lincoln and Kennedy loom large in the national consciousness, but it’s frequently overlooked that two other presidents were felled by assailants. In 1881, 20th president James A. Garfield died of a combination of infection and illness brought on by being shot weeks earlier. Twenty years later, William McKinley was gunned down at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York, shot twice by an anarchist assassin. McKinley actually lived several more days, even showing signs of improvement. However, gangrene set in and he died on September 14, 1901. Vice President Theodore Roosevelt was sworn in as president.

Roosevelt had already cut a famous public figure. His résumé to that point read like a novel. He’d been the governor of New York, assistant secretary of the Navy, a New York state assemblyman, and president of the New York City Board of Police Commissioners. In the military, he had ascended to the rank of colonel and was celebrated as a national hero for his role in the Battle of San Juan Hill during the Spanish-American War. Across his two terms as president, he would be a force. Not only was he the youngest president to take office (at 42), but he also blazed a trail in conservation (the engine behind the creation of national parks), championed the anti-trust battle, and fought for food and medicine policies that protected citizens. On top of that, his administration saw the beginning of construction on the Panama Canal and he won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1906 for the role he played in ending the Russo-Japanese War. Factor in that he has one of the most popular toys in history named after him (the Teddy Bear) and that he once finished a speech after being shot, it’s easy to see what a transformative figure he was in the 1900s and beyond.

1910s: Titanic Sinks

In their collection, Our Dumb Century, parody publication The Onion marked April 16, 1912, with the headline, “World’s Largest Metaphor Hits Ice-Berg.” While it’s obviously darkly funny as a punchline, it’s true that the story of Titanic sits at the intersection of a number of issues; it somehow manages to be emblematic of incompetence, hubris, and class struggle all at once. The hubris, of course, comes from the White Star Line’s labelling of their new liner as “unsinkable” (which is essentially an invitation for The Fates to say, “Watch this”).

Multiple feature films, TV movies, and documentaries have thoroughly established how the events of April 15 played out; suffice it to say that a good many mistakes were made and that priorities were placed on getting the more well-to-do passengers into the insufficient number of lifeboats ahead of the less wealthy passengers in steerage. Even The Saturday Evening Post weighed in on questions of blame at the time. It remains one of the most famous disasters in history, perhaps all the more compelling because of the ways it might have been avoided.

If one bright spot emerged from the story, it was the ascendance of the public profile of Molly Brown. Born and married poor, Brown became wealthy when her miner husband struck it rich; Brown became a philanthropist and well-known socialite. She’d been in Europe and only booked her passage on Titanic because it was the fastest way to get back home (her grandson had taken ill). As everything went to hell on the ship, Brown strenuously fought to get as many people onto the lifeboats as they could fit, even incurring the wrath of some of the ship’s crew. When the RMS Carpathia began rescuing survivors, Brown rallied other first-class passengers to make sure that the survivors from the so-called lower classes also had their needs met. Her record of charity and good works after the disaster is frankly staggering, including doing so much to help rebuild France after World War I that she received the French Legion of Honor in 1932.

1920s: The 19th Amendment

As much as a few modern pundits may want to undo it, one of the biggest steps forward for the United States was the 19th Amendment to the supreme law of the land, the Constitution of the United States. The text reads:

The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.

Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

Short and to the point, the 19th codified the right of women to vote. Ratification and certification of the Amendment in August of 1920 immediately made it possible for 26 million women to exercise their right. However, non-white women faced other obstacles placed by states (notably discriminatory practices in the South, such as literacy tests that targeted not only Black women, but other women of color). However, the addition of millions of citizens to the voting pool did have an impact, and the Suffrage movement would pave the way for increased opportunities for women in education and the workforce while laying the groundwork for expanded fights for women’s rights and civil rights.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

dear Editor:

I need to amend my earlier notes on the interview with Jacqueline “Peaches” Cruthers about the visit of

President Roosevelt at the ball game between the NYC team and the St. Louis team.

The soda drink he drank at the ballgame was Dr. Pepper, not Pepsi…close but no cigar.

The hot dog bun was new at the fair, as was the hamburger bun, and Dr. Pepper was being promoted.

Cracker Jack was NOT new, but, a new promotional cover for the box was being touted.

A L L flavors of ice cream was NOT new, but the cone was that President Teddy used in between hand fulls of Cracker Jack,

Folks seeing the President having a snack,; the President thus set a standard for A L L future baseball events to the

very present, Incidentally, some folks deny that “Toad Hall”, matches a home in Lakefield, and, yet Mrs Cruthers hosed an event in 2001 and she carefully showed how the description of Toad Hall in the children’s book matched exactly “Reydon Manor” in Lakefield…..every detail matches,

She held this comparison as a fund raiser for the Village’s Historically Society……I have a number of photos of

Laurance Grahame and the Fair Board-Committee.

Thanks for allowing me to amend the previous note……I’m sorry I slopped up on that.

BTW: because of Laurance Grahame acting as the President’s envoy, manage get nearly 80% of the displayed products were Canadian made, although it would be American owners, such as Quaker Oats for example.

Thanks.

Gord Young

Petrborough ON {still not in the 51st State]

Dear Editor:

Two important events happened while Teddy Roosevelt was New York Governor and President.

As Governor, he tied A L L major funding to libraries, from villages to New York City to use the Dewey Decimal System. To get money, the libraries had to have the Dewey in place, first as Braille help, along the spines of books, and, then in general use.

When Morris Michtim went to Oyster Bay, to ask Teddy’s permission to use his nickname for the toy bear he wished to market for the Christmas season, Teddy tied the permission to a royalty that Michtim had to pay towards a children’s outdoor program then being started by the New York State Parks Commission. The idea was put forward by Laurance H. Grahame, then sort of acting press secretary to Roosevelt. At Oyster By was Grahame’s cousin Kenneth Grahame, the children’s author more famously known for the book “Wind in the Willows”.

Mitchim was sort of outnumber, but, acceded to the request. The amount of royalty on those bears has never been determined, or, the amount raised to the children’s outdoor education, is also not known, but, it was a 5 year deal.

This information came from Laurance Grahame’s great grandaughter in an interview 20 years.

Laurance Grahame was then appointed as Scretary to the 1904 St. Louis Fair by Roosevelt as Roosevelt’s place on the board.

During the Fair, Roosevelt came to see the New York baseball team play the St. Louis team.

Almost always hungry, Roosevelt wanted something to eat.

Thus began the tradition of a hot dogs and Pepsi, and at the second game, the tradition of a hamburger and Pepsi.

Cracker Jack became “dessert”.

Years later of course, beer became the norm.