This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

During his September 30 address to a gathering of generals and other military officers at Quantico, President Donald Trump argued for an expansion of his controversial use of the military and other federal forces in American cities. “They’re very unsafe places,” he said of cities like Chicago, New York, San Francisco, and more, “and we’re going to straighten them out one by one. And that is going to be a major part for some of the people in this room. That’s a war, too. It’s a war from within.” And indeed, earlier that day a massive, destructive ICE raid on a Chicago apartment building had exemplified how such a federal government war on American cities and communities is already underway.

There are a number of historical precedents for such military attacks on American communities. In one of my most recent columns I argued that the controversial use of the National Guard in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina foreshadowed current events. In this October 2021 column I highlighted the use of aerial assaults on striking mine workers in 1920s West Virginia, one of a number of military responses to labor activism across American history. And in this January 2021 column I traced the multiple layers of the brutal 1921 Tulsa massacre, which included bombs dropped from the air on an American community.

Each of those events offers lessons for 2025 America. But it is another military-style attack on an American community, one that took place forty years ago, that represents the most direct predecessor to assaults like ICE’s in Chicago. The May 1985 police bombing of a Philadelphia neighborhood, known as the MOVE bombing due to the rationale for the destructive attack, lays bare the horrific and inevitable tragedies whenever we wage war from within.

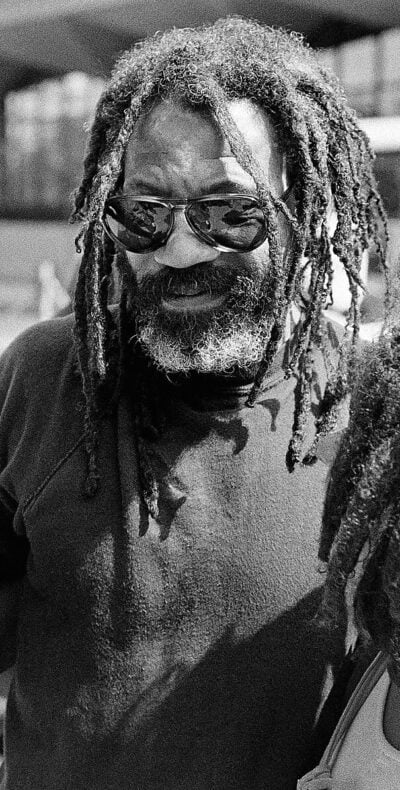

The community organization known as MOVE was founded in 1973 by a charismatic West Philadelphia activist known as John Africa. Born Vincent Leapheart, Africa was a Korean War vet who had been working as a neighborhood handyman for years when he developed the philosophical and spiritual ideas that became the basis for MOVE. The name was not an acronym but an indication of a collective desire to change and grow, one that the members reflected by (among other steps) moving together into a multi-home complex in the city’s Powelton Village neighborhood.

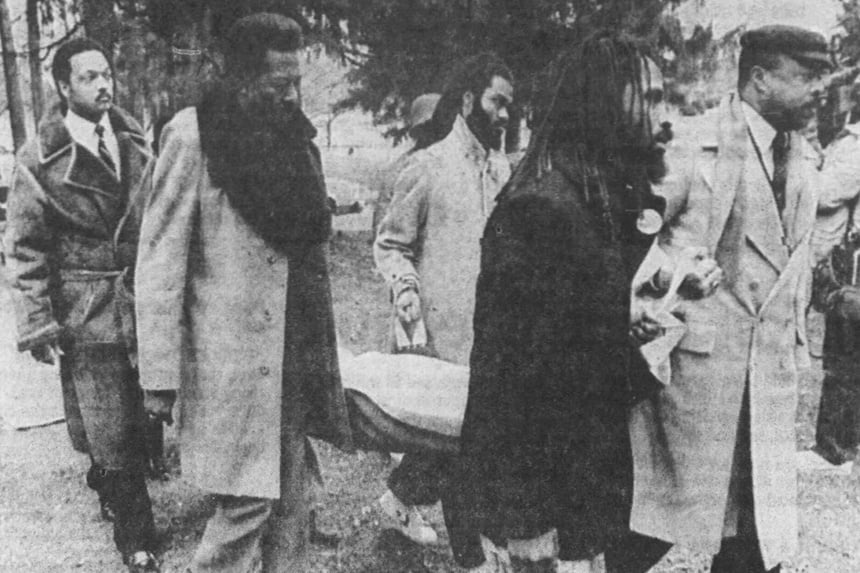

MOVE’s alternative lifestyle, conflicts with neighbors and other Philadelphians, and resistance to authority led to a number of charged encounters over the years with the police and city officials. The most violent was Mayor Frank Rizzo’s attempted eviction of the community’s members (including many children) in August 1978, which quickly spiraled into a confrontation between MOVE members and law enforcement officers. Many shots were fired and veteran police officer James Ramp was killed, although by whom remains in dispute; MOVE leaders claimed that they did not have functioning firearms and that Ramp was killed by friendly fire. In any case, the MOVE home was razed, the community expelled, and nine MOVE members were convicted of murder and sentenced to decades in prison.

For the next few years, MOVE focused much of its activism on fighting for those incarcerated members. But the organization continued to operate as a community and family as well, and in 1982 its members finally found a new permanent home, a row house owned by John Africa’s sister Louise Leapheart James and located on Osage Avenue in the West Philadelphia neighborhood of Cobbs Creek Park. That neighborhood had long been a historic hub of the city’s Black middle class, and MOVE’s presence there was once again a controversial one.

In May 1985, those tensions once again came to a head. On Mother’s Day, May 12, the city evacuated much of the neighborhood and positioned more than 500 police officers around the MOVE house. The next morning, Police Commissioner Gregore Sambor presented the imminent attack as a response to lawlessness, yelling through a bullhorn, “Attention, MOVE! This is America! You have to abide by the laws of the United States.” But it’s hard to see the military-style assault that followed as an illustration of law and order: The police were armed with machine guns and other heavy weaponry, and according to a subsequent investigation fired “over 10,000 rounds of ammunition in under 90 minutes at a row house containing children.” Multiple tear-gas canisters were also thrown into the house, and when MOVE members did not evacuate (understandably, given the constant barrage), Mayor Wilson Goode authorized the police to drop a two-pound satchel bomb, built with explosives provided in part by the FBI, out of a helicopter and directly onto the house.

Uploaded to YouTube by PBS NewsHour

The combination of the explosion and the fire it started killed 11 MOVE members, including five children; only two members survived, and both were badly burned. But the destruction and tragedy were far more widespread still. Although firefighters were present, they were ordered not to act for more than an hour, ostensibly so the fire could serve as a “tactical weapon” against MOVE. By the time firefighting efforts began they were far too late, and the fire consumed 61 houses, a multi-block radius of this historically Black middle-class neighborhood and community. In their extensive March 1986 report on the tragedy’s causes, the Philadelphia Special Investigation Commission (known as the MOVE Commission) would single out city and law enforcement authorities for their “reckless” and “unconscionable” bombing of the house. But no criminal charges were ever brought, and much of the Osage Avenue neighborhood remains either hastily reassembled or still unreconstructed to this day.

In May 1985 in West Philadelphia, as with every time the authorities have used military-style attacks against American civilians, communities, and cities, there were many factors that led up to the moment and its controversial decisions. But it’s difficult to separate the MOVE bombing from the more overarching and longstanding legacies of official, white supremacist attacks on Black and brown neighborhoods across America, especially those (like Tulsa’s “Black Wall Street”) which embody the community’s hard-fought successes.

What the MOVE bombing ultimately reminds us is that waging war from within is not just unconstitutional and contrary to our collective ideals; it also inevitably produces horrific and enduring tragedies.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now