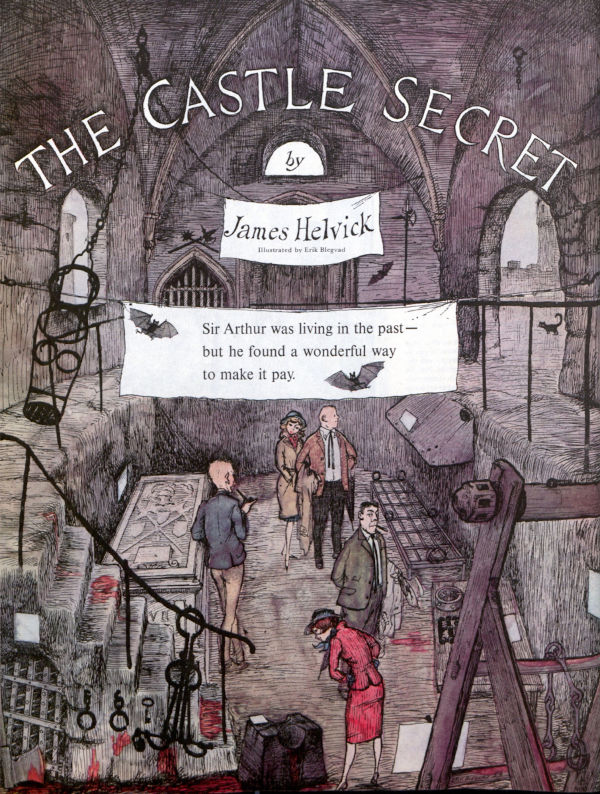

“The Castle Secret” by James Helvick

Claud Cockburn first received acclaim for his work as a journalist in England during the 1930s. He became most famous, however, for his affiliation with the British Communist Party during the Cold War. To avoid unwanted press, Cockburn began writing under the pseudonym James Helvick. He used the name to publish a number of works, including his 1951 novel Beat the Devil and the following story printed in the Post.

Published on October 17, 1959

A couple of ounces of pure, unblended English rain slid off the extended leaves of a wizened oak tree and struck Francis Manning just above the back of his collar.

“To think,” he said, “that that tree has been waiting to do that to me since the time of William the Conqueror.”

Nancy Manning said, “Hush, you’ll disturb the game.”

Francis Manning said, “Did you say game?” He looked at his wife sternly, but she continued to focus on the cricketers. Her expression was one of reverent attention. She was thinking about Sir Arthur Ludd.

Francis thought about him, too, with mingled awe, resentment and censure. He was irritably aware that it was this Ludd who, by remote control, had guided them and their daughter Francesca to the position in which they now found themselves — that is to say, England, inside a ruin, beside a lawn, on a bench, watching a cricket match.

During one of those regularly recurrent pauses — between what are called “overs” — which, as in Oriental music, are the very essence of cricket, Francis Manning said: “I yield to no man in my respect for Sir Arthur Ludd. I accept that he had the highest mind you or anyone else ever saw. I just want to say that there are times when I could wish you had never met him.”

He knew that this remark was unworthy of him, that he should no more criticize Nancy’s relationship with Sir Arthur Ludd than he would attack her for being moved by St. George, Sir Isaac Newton or the Charge of the Light Brigade. No fair-minded man could dare say that it was Sir Arthur Ludd’s fault that he had made such an impression upon Nancy all those years ago in blitztime England, where, by crude overstatements of her age and experience, she had promoted herself a tiny uniformed job ministering to the American Forces at Rainbow Corner and other relief points. Nor could you fault Nancy on account of the deep and lasting emotions aroused in her by this dedicated baronet, wounded at Dunkirk, invalided, an occasional lecturer to troops on technical aspects of warfare. It was in this capacity that he had first met Nancy. But he had also been immediately welcomed to the laboratories and back rooms of the Ministries of Aviation and Supply, where the brightest and most profound of Britain’s technicians were winning the war. Knowledgeable people said he was the brightest and most profound of them all. He also knew the work of the Restoration Dramatists by heart, and for relaxation used to translate them into Aristophanic Greek.

Nancy looked at her husband, saying nothing, for fear of disturbing the hush of the cricket field, but telling him with her beautiful eyes that he had said a coarse and hurtful thing. She had never concealed her feelings about Sir Arthur Ludd. Her memories of him during those months in England were not guilty but ennobling. She had made it clear when she married Francis that she intended to bring these memories along, together with a few pieces of fine furniture and glassware from her old family home in Vermont. Far from cluttering their Manhattan apartment, they would all serve to lend it a note of dignity.

And indeed the wraith of Sir Arthur had in one sense behaved itself unobtrusively. He was rarely spoken of. But one was made sharply aware that from time to time Nancy pursued one train of thought or course of action, rather than another, because she felt it to be in line with the ideals of Ludd. And sometimes when she criticized Francis, and later their daughter Francesca, Francis and Francesca instinctively knew that they must have done something or expressed some thought of a definitely un-Ludd nature.

It was unquestionably “Luddism” — as Francis referred to it when vexed — which had made up Nancy’s mind that this year they would go to England for the summer. At seventeen, Francesca did not seem always apt to appreciate the sort of things Sir Arthur Ludd “stood for.”

He stood for the real England. Not, as Nancy emphasized, that he had been narrow-minded. He had stood, as she recalled, for the real France and the real America too. These were all hard to find. You needed rigorous mental and spiritual training to get to them.

A determined trek to the real England would, Nancy said, do Francesca, and indeed all of them, a world of good. It would lift them, she implied, up toward the Ludd standard. It would be a gesture toward the higher values. Because Francis and Francesca had both chanced to be thinking in terms of Maine, the intervention of the unseen hand of Ludd in their holiday plans seemed particularly irksome.

To Jay Porter, who found himself sitting here damply with the three Mannings watching this cricket, the ghostly presence of Sir Arthur Ludd was even more oppressive. This youth Porter, from Indianapolis, being exposed temporarily to an Oxford education, had latched onto the Mannings while they were viewing Oxford at the end of the summer term. He had rejoiced to find himself at a table with fellow Americans in an overcrowded Oxford restaurant. He rejoiced further to note that one of these fellow citizens was a glorious girl gleaming at him only the table’s breadth away. There was conversation. There were introductions. Parents, in such circumstances, must be accepted as a necessary evil. Jay found the Mannings not evil at all. Yet there were times when he felt that the delightful Mrs. Manning was measuring him with her beautiful eyes against some invisible marking, and finding that he did not measure up.

He mentioned his impression to Francesca. “Probably it’s Ludd,” she said. “Maybe he finds you wanting — in nobility of character, high-mindedness, other-worldliness, strength of purpose, modesty, intellectual genius. Some je ne sais quoi that you don’t happen to have.”

“He’s a liar,” said Jay. “Who is he?”

Francesca explained about Sir Arthur Ludd.

“You don’t even know him?”

“Only mother does,” said Francesca. “But on a spiritual plane I’d say I’m well acquainted with him. I’m familiar with all his little ways.”

“And so it comes to pass,” said Jay, fixing her with burning eyes, “that under the dominance of this myth from the past, you trail about this country suffering experiences sometimes bizarre, sometimes merely horrible, and sometimes both at once, like this. Do you suppose, by the way, that this is the real England?”

“Nothing else was,” said Francesca, wriggling agreeably under the slither of the remaining raindrops over her skin. “People kept telling us ‘this isn’t the real England,’ and then we came to this historic township here with its castle famed in legend, and a cricket match going on and all. And if that isn’t the real England we’ll maybe have to throw in our hand.

“So there we all are,” said Jay, “poor hapless puppets in the hands of Ludd, the sadistic scientist from outer space.”

He sighed, continuing to gaze at Francesca. “You’re not keeping your mind on the game,” she said.

“Like a fish,” he said.

“Me? Like a fish?” Her voice rose to a small shriek. “I like that! Honestly — ”

“Like a fish out of water, I meant,” said Jay hurriedly. “Beautiful, gleaming and wriggling and all in the wrong environment and element.” He peered angrily around at the mackintoshed figures distributed sparsely about the benches.

“Well, mother thinks you’re an undesirable element,” said Francesca. “She feels we didn’t come here to pick up people like you that we could meet by the dozen back home.”

Nancy was turning to shush them again when an intense noise zipped across the playing field like a projectile and seemed to explode at the Mannings’ very feet. The players froze, then stared at the benches on the further side of the field. A moment later the noise was repeated. and this time was distinguishable as human speech.

“Nancy!” was the sound it made; and again, “Hi! Nancy!”

Looked at askance by the players, flaunting a raincoat like a cloak draped from the shoulders of a rowdy sports coat, a bulky figure came straight across the field in a swaggering hobble. From a distance of thirty yards the man began to wave enthusiastically and actually to converse, as though he were talking across the width of a drawing room.

“Nancy, my dear!” he shouted. “Ages since I saw you! What on earth have you been doing with yourself? How’ve you been? Awful lot of ’flu about this year, though mind you the reports may be exaggerated. Nothing to be frightened of.”

By this time he was clumsily hurdling the intervening benches. Members of the Manning party saw looming above them a shoe-leathery face, scarred here and there, it seemed, by a slip of the cobbler’s hand; a Roman nose protruding nobly from it; and eyes both roving and intent with a droop of the left eyelid that made you think of a pirate’s patch.

“Arthur!” said Nancy. “It’s just wonderful to see you. Francis, this is Sir Arthur Ludd. Arthur, this is my husband.”

“Splendid! Splendid!” said Sir Arthur. They started to make room for him on their bench, but he had already hobbled round it and seated himself on the bench immediately behind them.

“No use trying to talk now in this utter discomfort,” he said, leaning forward. “What we’ll do is, we’ll watch this thing for a bit and then we’ll all go and I mean to say as it were.”

Peering around for a moment, Jay saw him extend his legs and throw himself into a semisupine attitude, his arms extended in each direction along the back of the bench.

Francis, Francesca and Jay Porter turned their attention to the game in an awed silence. The personal materialization of Sir Arthur Ludd was as disconcerting as would be a sudden wave and cheery greeting from a symbolic statue on some public building. His presence immediately behind made them all feel that it was their duty to watch England’s national game with an increased semblance of interest.

The ecclesiastical quiet, briefly broken by the eruption of Sir Arthur, had again settled over the field, emphasized rather than shattered by the sound which, Jay was happy to remember, was properly known as the “crack of leather on willow.” The fans maintained an almost eerie silence, commenting on the game chiefly by nods, shakes of the head, and an occasional sigh as of scorn or despair.

“Surely,” whispered Jay to Francesca, “there’s a bit in this piece where someone calls out ‘Play up, and play the game!’ Or have I my facts wrong?”

He had not. At that very moment a hoarse voice shattered the moist peace with an abrupt staccato cry.

“Play up, and play the game!” was its utterance. It ceased, cut off as sharply as it had begun.

Electrified by this noise which came from immediately behind them, the Mannings and Jay Porter looked round. Sir Arthur Ludd was still in his partially recumbent position. His chin had fallen forward to rest on his gaudy tie, the snap brim of his hat almost covered his face. Some of the fans had turned round, too, in irritable curiosity, but there was nothing to connect Sir Arthur with that in spiriting exhortation.

Uneasily the spectators in front of him settled down to appreciate whatever was going on on the pitch. They did not settle for long. The shattering voice came again.

“Jolly well bowled, sir!” it suddenly shouted, “Jolly well bowled!”

Since the bowler was not in action at all at the moment, this piercing piece of applause struck spectators and players alike as painfully irrelevant. All gazed in the direction of Sir Arthur, but it was as though he had never moved. A man sitting next to him gave him an exasperated little nudge, and at the same time moved himself an inch or two away from him on the bench in a gesture of disassociation. Sir Arthur snapped up his chin and pushed his hat back on his head and looked about him with a lofty expression. The people who had been eying him censoriously quickly looked away again. He leaned forward and tapped Francis on the shoulder.

“I don’t know how you feel about it, old boy,” he said, “but it seems to me we’ve seen about enough of this. There’s a bar in the pavilion. Why don’t we all go and so to speak — ”

Nancy’s expression, as Sir Arthur led the way toward a chalet-type wooden building at the end of the field, said that this certainly was going to be a privilege.

“Mother looks,” said Francesca, “as though she was hoping for the best from us and expecting the worst.”

Grimly, Francis braced himself for some high-minded conversation. He felt it his duty to his wife to tell Francesca and Jay to brace themselves for the same. Francesca sighed. Jay Porter looked lovingly at her and glared at the swaggering raincoat ahead of them.

“J’ever hear,” Sir Arthur was saying as they filed into the pavilion, “that story I read somewhere about the man that died suddenly while watching a cricket match? Over three inches of rain had fallen for seven runs, and it was supposed the excitement killed him.” He laughed loudly. A party of Anglo-Englishmen at one end of the small bar displayed disgust at the unseemly jest. Two American airmen at the other end sniggered happily. Sir Arthur rounded on them.

“Just because,” he said sternly, “you people prefer playing rounders with a hard ball, there’s no occasion to sneer at our national game.”

“Well, anyway we paid to see it, didn’t we?” said one of the airmen.

“Not at all,” said Sir Arthur. “You paid to see these magnificent grounds and this historic castle, including its horrific dungeons and the boudoir where Henry VIII possibly made his first pass at Anne Boleyn. And then, today being Saturday, you’ve got the splendid display of cricket at its best thrown in. How much more, may I ask, do you expect for a lousy four shillings and sixpence, with just a very few extras here and there?” The airmen looked at him as unfavorable as did the English party at the other end of the bar.

“J’ever notice,” said Sir Arthur to Nancy, “that something about the game of cricket brings out the worst in everyone? Evil, sour expressions are what we see around a cricket ground. Though mind you,” he added loudly, “it may be of course that only sour and evil people ever go to watch such games.”

“But you were watching, Sir Arthur,” said Francesca. “You were shouting and encouraging them.”

“Wasn’t actually watching,” said Sir Arthur; “just sitting meditating, more or less contemplating my navel. But the crowd likes to hear a cry of ‘Well caught’ or something of the kind from time to time, so I give it them every so often.”

“But why do you come at all if that’s how you feel about it?”

“To make money,” said Sir Arthur. “Ever since I opened the castle grounds to the public I spend every Saturday at least padding about, helping to sort of, as it were. By all means buy us another big drink all round, Manning old man. As I say, it encourages the masses to see the owner in the flesh. People natter about the Duke of Bedford and that three-ring circus or whatever it is he runs at his place, but what I say is where else can you put down a mere four and six pence and be sure of seeing a baronet of ancient lineage and a brilliant scientist to boot?”

He slapped his hand on the bar and looked challengingly around at the company.

“So this is your place?” said Nancy. “I do admire your enterprise, but it must be sad having to sort of hire it out this way. I remember how you used to feel about the family traditions.”

“Comes to that,” said Sir Arthur, “the Ludds have always been in the looting line from way back. Looting and low cunning — that’s how we got the castle in the first place, changing sides at the right moment in the Wars of the Roses. I love to hear the jingle of the cash register behind the bar there, and the merry click of the turnstiles. I love money; don’t you, Manning?”

“Great stuff!” said Manning, in a tone hearty but bewildered.

“And of course the money goes to keeping up your laboratory,” said Nancy. “I read in a magazine somewhere that some o f your researches might ultimately save as many lives as penicillin.”

“Oh, I chisel most of the lab money out of the government,” said Sir Arthur. “Easy enough, you know, if you know where to start chiseling. Thank God, a little title and the old-school tie are still sometimes worth a bit more than honest merit. I spend most of what I make out of this castle racket on strictly personal luxuries — wine, really good cigars, you know, that type of thing.”

“And all the time,” breathed Nancy rather anxiously, “you may be on the verge of something that will save all those billions of lives.”

“Can’t say,” said Sir Arthur. “It’s a tossup. I’m the best man in England in my line, but even so it’s just a tossup. And by George! when one looks around at the citizenry one wonders whether there hasn’t been a bit too much life saving in the past. I intend no personal offense,” he added with an unctious smile at one of the Englishmen who seemed to be on the point of angry protest. “Dear Nancy, how happy I am to see you. Should we all take a little stroll round the place? I like to have a quick look round before closing time.”

Beside a path behind the pavilion an irregular semicircle of large stones was visible in the rank grass. A neatly painted notice said: “Possible site of Druid ring and altar. Here young maidens may have been bound shrieking on a midsummer’s night, and at dawn pitilessly sacrificed to the Sun God.”

“They may, at that,” said Sir Arthur.

“Is there historic evidence for it?” asked Jay.

“Naturally not,” said Sir Arthur. “We are dealing here with the prehistoric.”

Where the path adjoined a well-trodden dirt track a signpost announced: “To the camp for nudists.”

“A small idea I picked up from the Duke of Bedford again,” said Sir Arthur. “The papers were full of his plans for inviting one of the nudist societies to camp on his grounds.”

“I don’t know that I specially want to see a lot of nudists,” said Francesca, as they moved in the direction of the sign.

“You aren’t likely to,” said Sir Arthur. “It’s all right for Bedford down there by the muggy Thames, but I can’t see any society of nudists being fools enough to come up to a chilly rainswept place like this. I don’t want any charges of misrepresentation, and this, as the sign indicates to everyone of average intelligence, is simply a camp available to nudists should they wish to take advantage of it. Do any business today, Tom?” he inquired of an elderly man who was folding a small collapsible chair and preparing to leave his position in front of a low fence, enclosing what seemed to be an extensive copse where the undergrowth grew thick beneath the trees. “Tom,” explained Sir Arthur, “has the binocular concession here. Lets them out at a shilling a time for people who want to get a good view of any nudists there may happen to be.”

“Only six bob today, sir,” said the old man. “There ain’t the interest in the naked human form there used to be. I suppose the movies have damped the ardor, as you might say.”

“But if there aren’t any nudists there anyway?” said Jay.

“In my young days,” said the old man sternly, “we’d have paid our bob just on the off chance.” He looked Jay up and down with sad contempt and ambled away, the binoculars which had been in such poor demand bumping against his hip.

As they approached the castle itself, the last of the bedraggled visitors were leaving, complaining loudly among themselves at the extortionate price they had been asked for tea and buns. “Imagine that,” said Sir Arthur. “Complaining about a few bob extra for tea in such sur- roundings. Some of these people have no historic sense.”

“Rugged-looking old place,” commented Francis Manning.

“You bet it’s rugged,” said Sir Arthur. “I had to pay a gang of workmen a packet to knock it about till it got the proper fifteenth-century tone. Actually, most of it was run up less than a hundred years ago by my great-grandfather when he made a bit of money out of a small coal mine he chanced to find. At that, he forgot battlements. Had to put them on myself. In my opinion to invite the public to a castle that has no battlements is equivalent to obtaining money under false pretenses. It’s the same with dungeons.”

By way of a long winding staircase they descended to the dungeons. Here was black gloom, alleviated only by the faint light from slits high in the walls.

“Mind the rack, my poppet!” Sir Arthur cried in agitation as Nancy bumped against a dimly seen contrivance of poles, rollers and pulleys. “It’s good, but it’s flimsy. I knocked it together myself. And now that all those eager students of the medieval way of life have gone, we might have a little light on the scene.” He snapped a switch, flooding the large circular room with electric light. “When I opened for business,” he said, “believe it or not, this place was scarcely furnished. Not a rack, not a thumbscrew, not a garrote in the place. Terrible condition to leave a dungeon in.” While his visitors surveyed a satisfying array of instruments of torture, each with its notice luridly describing its uses, Sir Arthur approached what seemed to be a stone coffin set against one of the walls. Its top was roughly chiseled with some vaguely heraldic device and the notice beside it said: “Tomb of the first Sir Arthur Ludd circa 1300. Please do not touch.” Sir Arthur drew a key from his pocket, inserted it in a lock cunningly concealed in the heraldry, and threw back the lid.

“In addition to thumbscrews and such,” he said, “another thing I personally expect to find in a cellar is booze. Now what will you so to speak — ”

The supposed tomb of the first Sir Arthur was indeed well stocked both as to quantity and variety of liquor. “Porter, my dear boy,” said Sir Arthur to Jay, pouring whisky lavishly and setting the glasses on a table otherwise occupied only by a number of skulls, “just pull up a couple of coffins from the corner over there, will you, and we’ll make ourselves comfortable.”

Having drained his glass and refilled it, Sir Arthur patted Nancy cozily on the thigh and looked her over admiringly. “Lovely,” he said. “All such changes as can be observed are for the better. You don’t mind” — he turned to Francis — “my making passes at your wife? It isn’t as though I saw her every day.”

Francis also drained his glass and re-filled it. “It seems to me,” he said, his voice rising somewhat, “that you’ve been making passes at my wife for the past eighteen years or so. Furthermore, she has reciprocated your — so far as I am concerned — unwelcome advances. You and your high-mindedness! I could sue you for alienation of respect.”

“What the devil d’you mean?” boomed Sir Arthur, his nose deep in his glass. “Are you aspersing this woman? I could sue you for slander. We may be a second-rate power, but we’ve still got our lawyers.”

Nancy rose suddenly and stood over Sir Arthur, her foot tapping dangerously on the stone floor.

“You’re entertaining us very nicely, Arthur,” she said, “but what about your ideals and higher aspirations that you used to tell me about?”

“Yes, indeed,” interrupted Francesca. “Those ideals and standards of yours have been pushing me around for years.”

“And I, let me tell you,” said Jay Porter, also rising and standing over the baronet, “have suffered the indignity of being looked on as an unworthy squire of this beautiful and innocent girl because the Ludd yardstick says so. You’ve deliberately humiliated me.”

“But I mean as it were sort of,” said Sir Arthur, “I’m a perfectly ordinary sort of a chap.”

“That’s not the way we heard it,” said Francis.

“You wormed yourself into our home as a paragon,” said Francesca. “You caused friction and resentment.”

A mournful voice was heard calling from a long way off at the top of the stairs.

“Have you got the key of the blood cupboard there, Sir Arthur? Execution block needs a new coating. Lot of visitors today and you can’t stop some of them fingering the bloodstains.”

Sir Arthur got to his feet. “Excuse me,” he said. “There’s a special bloodstain I make up in the lab. They must put it on in the evening; otherwise it’s still sticky in the morning. Bit too realistic.”

The visitors stared at one another as the noise of his feet stumped away up the stairs.

“And that plausible rogue,” said Francis after a silence, “has been imposing on us all these years.”

“He’s a genuine scientist,” said Nancy.

“I don’t doubt it. The point is that as a high-minded arbiter of ethical and social behavior he has been an impostor all this time. I told you I wished you had never met him.”

“But I’m so glad I’ve met him again,” said Nancy. “Otherwise he’d have gone on and on forever being a cause of friction. As a common human being he’s harmless.”

“As a common human being,” said Francesca, “he’s sort of nice.”

“Maybe,” said Francis, “but as an ideal he was hell.”

“But he won’t be any more,” said Nancy. “As an ideal I’ve dropped him.”

Francis kissed her warmly.

“In that case, may I yet dare to hope?” said Jay Porter. He kissed Francesca lightly on the cheek.

Sir Arthur came stamping down the stairs. “Had to find the key for him,” he said. “People like blood. Have some more whisky. But wait a minute!” He had an air of sudden recollection.

“Weren’t we just having an awful row?”

“It’s over,” said Francis. “You’ve exploded and we like you better that way.” “Your presence in the flesh has brought happiness and harmony to all” said Jay. “Now that you’re a human being,” said Francesca, “I shall call you uncle.mI think I’ll kiss you.”

“Do that,” said Sir Arthur, “and then I’ll kiss your mother.”

“Meanwhile, I’ll have some more whisky,” said Francis.

“It’s good stuff,” said Sir Arthur. “Been maturing for an awful long time. The only genuine antique on the place.”

Featured image: The visitors surveyed the instruments of torture, each with a notice of luridly describing its uses. (Erik Blegvad, SEPS)

The President and the Bully

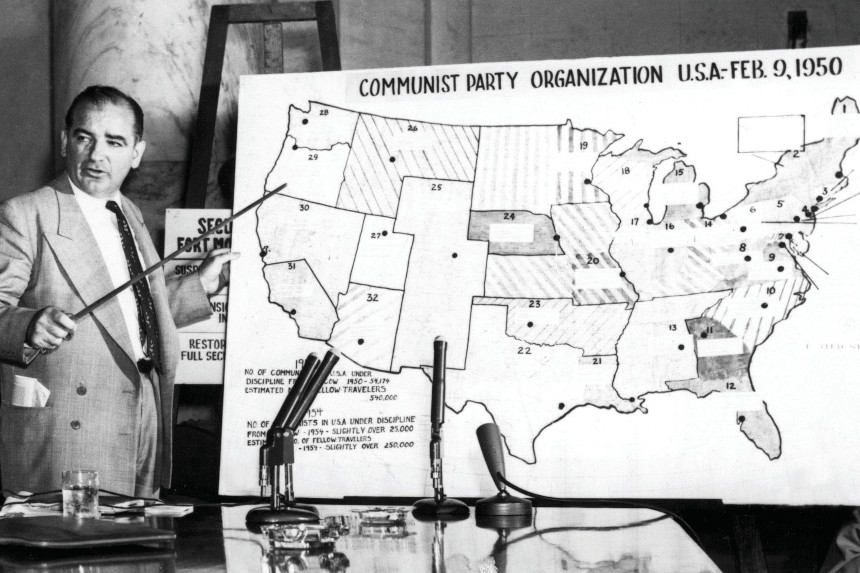

Dwight David Eisenhower was a man of inscrutable contradictions. Our 34th president loved Shakespeare almost as much as he did cowboy novels, and he listened to Beethoven’s “Minuet No. 2” right along with the “Battle Hymn of the Republic.” At the beginning of his presidency, this avatar of the armed services threatened a nuclear strike against North Korea, although by the end he was sounding alarms about the “disastrous rise” of America’s military-industrial complex. Nowhere were those dueling natures more apparent than in his mercurial and at times mystifying approach to the subject of Senator Joe McCarthy.

While Ike told his family and friends that he detested McCarthy and all that he stood for, he vacillated between strategic retreat and frontal assault, seeming uncertain, for once, about the wisest combat strategy. It wasn’t easy for a professional soldier, much less a venerated five-star general, to wage peace. At times, he tried a middle course of behind-the-scenes obstruction. But during the critical first year of his administration, when the Wisconsin senator was at his reckless worst, President Eisenhower pursued a policy of appeasement that infuriated McCarthy haters as much as it delighted the senator himself.

Milton Eisenhower, Dwight’s younger brother and closest confidant, saw up close how McCarthyism and McCarthy bedeviled the commander-in-chief. On the one hand, the president “loathed McCarthy as much as any human being could possibly loathe another, and he didn’t hate many people,” Milton said. On the other hand, his brother knew that hating only had value if acted upon. “I wanted the president, in the strongest possible language, to repudiate him,” said Milton, to “tear McCarthy to pieces.”

Arthur Eisenhower, the oldest sibling and a sober-minded banker, also pushed Little Ike to take on the Wisconsin senator, whom he called “the most dangerous menace to America.” “I think of McCarthy, I automatically think of Hitler,” added Arthur, knowing there was no specter more likely to rouse the former Allied supreme commander to action than that of the Nazi murderer he’d vanquished a decade earlier.

While President Eisenhower listened, he didn’t act. His presidential papers make clear that he was privately fuming at McCarthy, who had vilified his mentor, General George Marshall. But Ike, cautious by instinct and patient by habit, lectured his brothers and his aides that to McCarthy, there was no such thing as bad publicity. Confronting him head-on would just guarantee him more of the spotlight and could make him a martyr. “I developed a practice which, so far as I know, I have never violated,” the president explained in a 1954 letter to a friend. “That practice is to avoid public mention of any name unless it can be done with favorable intent and connotation; reserve all criticism for the private conference; speak only good in public. This is not namby-pamby. It certainly is not Pollyanna-ish. It is just sheer common sense. … The people who want me to stand up and publicly label McCarthy with derogatory titles are the most mistaken people that are dealing with this whole problem, even though in many instances they happen to be my warm friends.”

On another occasion, the warrior-turned-politician confided, “That damn fool Truman created that monster. [McCarthy] didn’t exist until Truman went eyeball-to-eyeball with him. Whenever a president does that with any individual he raises that individual to the president’s level, and Truman was too stupid to understand that.”

So instead, Eisenhower waited, the way he had with D-Day and other great battles during the war in Europe, convinced that McCarthy would do himself in. Ike offered occasional critiques, along with a muted counterpoint to Joe’s raging bravado. “I was raised in a little town of which most of you have never heard. But in the West it is a famous place. It is called Abilene, Kansas,” he said in one of his veiled commentaries, broadcast over national radio and television in November 1953 and, as was his way, not naming the bullying senator. “That town had a code, and I was raised as a boy to prize that code. It was this: Meet anyone face to face with whom you disagree. You could not sneak up on him from behind, or do any damage to him, without suffering the penalty of an outraged citizenry. If you met him face to face and took the same risk he did, you could get away with almost anything, as long as the bullet was in the front.”

Takedowns like that were so veiled that much of America missed Ike’s point, and so tepid that Joe was undeterred. Mainly the president went on with his normal White House routine, while newspapers published so many photographs of Ike swinging golf clubs and casting fishing lines that the public sometimes wondered who was running the government. That uncertainty grew as reporters tried to parse his rambling, garbled answers at press conferences. Was he being rightfully circumspect or was he out of his depth? The verdict at the time was that his was a do-little presidency, a boring and safe aftermath to the wildly eventful Roosevelt and Truman tenures. Ho hum.

Eisenhower outdid Harry Truman in combing the government for security risks and trying to wrest from McCarthy the mantle of top-drawer commie-slayer.

Not so, a lineup of recent Eisenhower biographers tells us. Neither the peace nor the prosperity of the ’50s happened by chance, and the easygoing Ike was doing more than playing golf. His steadying hand was everywhere — ending the Korean War, preserving the New Deal, constructing a nationwide highway network, even taking on Jim Crow segregation by signing, in 1957, the first civil rights law since Reconstruction. The sly presidential fox was misleading Americans on purpose, projecting a grandfatherly calmness that bred public confidence and, not incidentally, helped him outmaneuver adversaries within his own political party. There was no clearer instance of that approach, the president’s defenders say, than his treatment of Senator McCarthy. The seasoned general’s willful silence was a calculated misdirection aimed at ensnaring the runaway senator. Eisenhower wisely “held his fire until McCarthy became open to attack by any right-thinking American,” said Princeton Professor Fred Greenstein, who came up with a name to celebrate that kind of governance by guile: The Hidden Hand.

The Hidden Hand is a convincing way to unravel the riddle of Eisenhower’s surprising successes building highways, expanding Social Security, increasing the minimum wage, and pushing forward on civil rights, but historians have been far too forgiving of the president when it comes to Senator McCarthy. For starters, Eisenhower did more than turn his other cheek. As far back as the 1952 campaign, he signaled his willingness to mollify McCarthy by dropping from a speech in Wisconsin his spirited defense of George Marshall, an about-face that Ike’s pal General Omar Bradley said “turned my stomach.” His aides claimed Eisenhower had to back off for electoral reasons, even though he was on his way to winning 39 of 48 states and would have won in a landslide even without McCarthy’s support or Wisconsin’s electoral votes. Eisenhower advisor and 1948 Republican presidential nominee Thomas Dewey had warned that McCarthy would become his “hair shirt” unless Ike hit him early and hard. Ike said he would, then didn’t. Syndicated columnist Drew Pearson sounded a similar alarm but said, “It was obvious from the questions [Eisenhower] asked that he just did not understand” why the columnist was cautioning him. Instead, according to Pearson, the candidate’s cowardly retrenchment on Marshall tipped off the Neanderthal wing of his party that they could “handle” him. Joe, too, smelled blood in the water.

Attack he did, from the instant Eisenhower moved into 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, with the White House failing to push back. That spring, the administration let McCarthy elbow his way into U.S. foreign policy after the senator unmasked the embarrassing fact that our closest allies were shipping goods to our Korean War enemies. In June, the president stood up to the senator over whether left-leaning tomes should be stripped from the shelves of U.S.-supported libraries around the world, but when McCarthy fired back, Eisenhower retreated. Ike stripped J. Robert Oppenheimer of his security clearance when McCarthy threatened to investigate the nuclear scientist and shunned Senator Margaret Chase Smith once she became Joe’s enemy. White House minions and even cabinet officers got the message. The secretary of state gave McCarthy the widest of berths and a say on security clearances; the attorney general brought no indictments in the wake of reports from two Senate committees lambasting McCarthy; and J. Edgar Hoover acted as though he worked for the senator instead of the attorney general and president.

Even more basic to McCarthy’s success, the president never challenged the senator’s meat-and-potatoes premises: that merely believing in communism was sufficient to pose a peril, and that Soviet subversion threatened the stability and safety of America. Determined not to repeat his predecessor’s presumed failure, Eisenhower even outdid Harry Truman in combing the government for security risks and trying to wrest from McCarthy the mantle of top-drawer commie-slayer. No matter that there were few if any real spies left by the time the general moved into the White House. The upshot was that the Red Scare dragged on longer than it had to. As for the constitutional protection that McCarthy undercut most often, President Eisenhower saw nothing wrong: “I must say I probably share the common reaction if a man has to go to the Fifth Amendment, there must be something he doesn’t want to tell us.” It was more delicate than Joe’s branding witnesses Fifth Amendment Communists, but just barely.

This ranking officer had never liked to wage war unless he was certain he would win. But holding back until the senator self-destructed — which happened in 1954, during the famous Army-McCarthy hearings — meant that, in the meantime, the country would pay a searing toll. The White House stayed silent while McCarthy upended the career of Reed Harris of the International Information Administration and rattled the Harris family to the point that his wife Martha later killed herself. Similar fates befell scores of other federal officials. It was on Eisenhower’s watch and partly thanks to his coattails that McCarthy was elected to an office that allowed him to chair the Senate Subcommittee on Investigations, where he was able to wreak such havoc.

What could and should this president — the second in a row to be stymied by the rabble-rouser from Wisconsin — have done differently?

He ought to have ordered his FBI to plug its leaks to McCarthy, the State Department to stop cowering and backpedaling, and the International Information Agency not to “deshelve” its overseas libraries. Instead, said Martin Merson, who watched it all from a senior perch at the Information Agency, “the president made the mistake in those early days of not believing enough in the people, of feeling that he had to accommodate himself to the so-called practical politicians, to make compromises, to heed the cry of expediency.” But whereas Merson at least listened to the president’s justifications, McCarthy target James Wechsler offered this harsher verdict: McCarthy “was not superman; he was nourished more by the weakness of those who should have resolutely challenged him — most notably Dwight D. Eisenhower — than by any mysterious resources. There must have been many moments when he shook with laughter over the conduct of those he was harassing; surely he must have enjoyed Mr. Eisenhower’s austere refusal to ‘indulge in personalities,’ the craven formula devised early at the White House for the preservation of internal Republican peace and quiet.”

Ironically, the one area where pollsters said Americans doubted their commander-in-chief was his decisiveness — qualms that an iron-fisted response to McCarthy could have put to rest. “At a time when the public would doubtless have welcomed some kind of a statement on McCarthy by the president — either pro or con — he offered nothing,” said John Fenton, then the managing editor of the Gallup Poll. Drew Pearson still hoped he might, telling his diary in November 1953 that “it’s barely possible that Ike will now get off his fat fanny and realize that the chips are down, that he can’t temporize with a would-be dictator.”

Insiders were even more restless. At the same moment Pearson was venting in his journal, C.D. Jackson, Eisenhower’s special assistant on the Cold War, was penning a letter to White House Chief of Staff Sherman Adams. “Listening to Senator McCarthy last night was an exceptionally horrible experience, because it was in effect an open declaration of war on the Republican President of the United States by a Republican Senator,” Jackson wrote in response to McCarthy’s national TV and radio address, in which he charged that the Truman administration had “crawled with communists” and that the Eisenhower administration was only marginally better. “I hope,” Jackson added, “that this flagrant performance will at least serve to open the eyes of some of the president’s advisers who seem to think that the senator is really a good fellow at heart. They remind me of the people who kept saying for so many months that Mao Tse-Tung was just an agrarian reformer.”

At times Ike seemed aware of his own vacillating and doubtful of the Hidden-Hand strategy, as reflected in notes to himself and his counselors. “I continue to believe that the President of the United States cannot afford to name names in opposing procedures, practices, and methods in our government. This applies with special force when the individual concerned enjoys the immunity of a United States Senator,” he wrote in 1953 to a friend who chaired the board of General Mills. “I do not mean that there is no possibility that I shall ever change my mind on this point. I merely mean that as of this moment, I consider that the wisest course of action is to continue to pursue a steady, positive policy in foreign relations, in legal proceedings in cleaning out the insecure and the disloyal, and in all other areas where McCarthy seems to take such a specific and personal interest. My friends on the Hill tell me that of course, among other things, [McCarthy] wants to increase his appeal as an after-dinner speaker and so raise the fees that he charges.”

Other times, unable to tolerate the pain he felt biting his tongue regarding McCarthy, this thin-skinned president looked for scapegoats — Democrats, misguided staffers, or, in this case, the press. “No one has been more insistent and vociferous in urging me to challenge McCarthy than have the people who built him up, namely, writers, editors, and publishers. They have shown some of the earmarks of acting from a guilty conscience — after all, McCarthy and McCarthyism existed a long time before I came to Washington,” he wrote in March 1954 to another businessman-friend. “The area in which all of this really hurts is the adverse effect upon the enactment of the program of legislative action I have recommended. We have sideshows and freaks where we ought to be in the main tent with our attention on the chariot race.”

Two weeks later, in March 1954, he finally said he’d had enough and would tell the world how much he loathed the Wisconsin senator. It was liberating, as his press secretary, James Hagerty, reported in his notes on that day’s staff briefing, where McCarthy once again was topic number one. “I’ve made up my mind you can’t do business with Joe and to hell with any attempt to compromise,” Eisenhower told his assembled aides, not recognizing that he was echoing the sentiments of the predecessor he scorned, Harry Truman. Walking away with Hagerty, Ike added: “Jim. Listen. I’m not going to compromise my ideals and personal beliefs for a few stinking votes. To hell with it.”

At a press conference later that morning the president was asked whether Joe had the right to cross-examine witnesses in hearings called to investigate his own allegedly improper encounters with the U.S. Army. “In America,” Ike answered, “if a man is a party to a dispute, directly or indirectly, he does not sit in judgment on his own case.” It was the president’s most public and direct assault on McCarthy, but it was hardly the break that Ike had promised barely an hour before, or that Milton Eisenhower, C.D. Jackson, and others said was vital to curb a senator whom Jackson called “a killer abroad in the streets.”

The senator was ultimately brought down when the public saw at those Army-McCarthy hearings how reckless and ruthless he was, and to his credit, the president worked behind the scenes to ensure the Army stood fast against the demagogue from Wisconsin. In December 1954, the Senate found its own equivalently elusive backbone, condemning its colleague in a way that amounted to a political death sentence.

Looking back, it’s clear that Senator McCarthy’s reign of terror should never have lasted as long as it did. It’s also clear that President Eisenhower was the one national figure with the patriotic service and popular following who could have neutralized the out-of-control lawmaker. The president’s monthly approval numbers in 1953, at the height of McCarthy’s power, never dropped below 61 percent and topped out at 73 percent, the kind of fawning most leaders can only dream about and that McCarthy never even approached. In 1954, and in 12 of the 19 years between 1950 and 1968, Americans voted Eisenhower their favorite person in the world. And Ike, alone among Americans, had access to unvarnished reports from the FBI, CIA, and loyalty boards of every federal agency, laying out the limits of government treason and the breadth of McCarthy myth-making. He had the power and knew the lies.

But the most powerful general in America’s history, the supreme commander of an Allied force that crushed Adolf Hitler, shrank from confronting a drunken bully. At this milestone moment, rather than a Hidden Hand guiding the country, the Eisenhower waiting game looked more like an Empty Glove.

Larry Tye is the best-selling author of Bobby Kennedy and Satchel. Previously an award-winning reporter and national writer at the Boston Globe, he now runs the Boston-based Health Coverage Fellowship. For more, visit larrytye.com.

Excerpted from Demagogue: The Life and Long Shadow of Senator Joe McCarthy by Larry Tye, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2020

This article is featured in the September/October 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Everett Collection Historical / Alamy Stock Photo

Vintage Ads: Travel in the 1950s

Want to look at all of our ads from the 1950s? Become a member! Members receive 6 issues of The Saturday Evening Post per year plus complete access to our online archive dating back to 1821.

March 3, 1951

(Click to Enlarge)

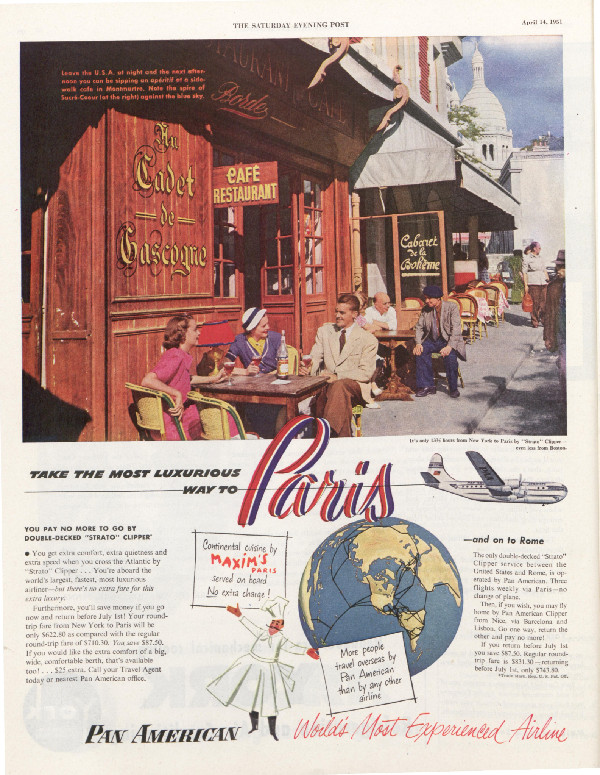

April 14, 1951

(Click to Enlarge)

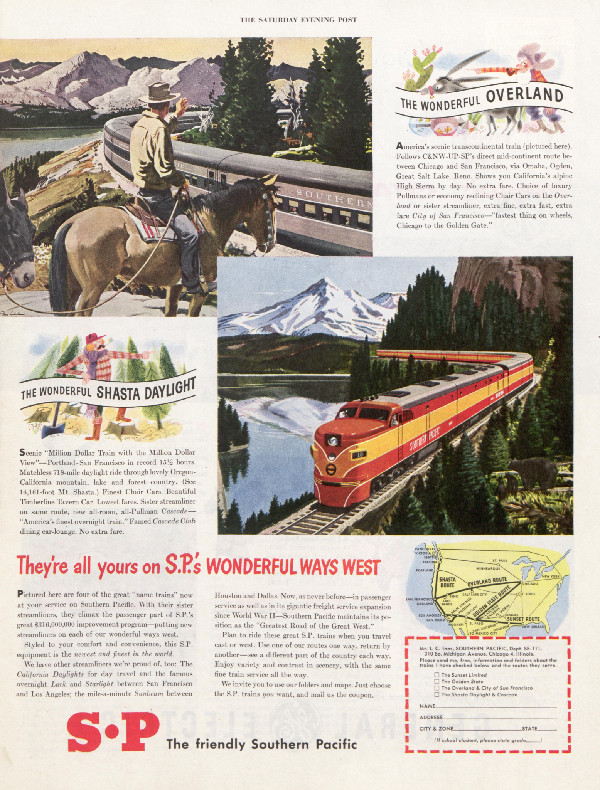

November 25, 1950

(Click to Enlarge)

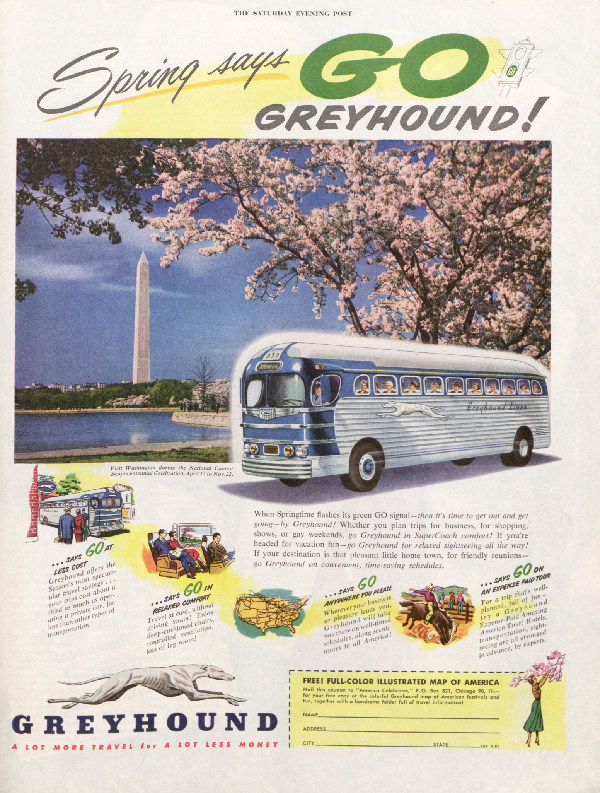

November 18, 1950

(Click to Enlarge)

December 1, 1951

(Click to Enlarge)

July 1, 1950

(Click to Enlarge)

June 24, 1950

(Click to Enlarge)

March 25, 1950

(Click to Enlarge)

March 1, 1952

(Click to Enlarge)

October 6, 1951

(Click to Enlarge)

Want to look at all of our ads from the 1950s? Become a member! Members receive 6 issues of The Saturday Evening Post per year plus complete access to our online archive dating back to 1821.

The Accident of McCarthyism

By the time World War II ended, America had paid a high price to stop men who rose to power through hatred and suspicion.

But then came Senator Joseph McCarthy and, with him, McCarthyism. The word wasn’t his invention. It first appeared in The Christian Science Monitor. It was a movement that created a culture of suspicion and mistrust, turned people against each other, and cost thousands their dignity, their jobs, and even their lives.

It’s all the more astonishing, then, that McCarthyism could almost be considered an accident, according to Larry Tye, author of Demagogue: The Life and Long Shadow of Senator Joe McCarthy.

McCarthy had been elected senator from Wisconsin in 1946. In 1950, his re-election was threatened by past misdeeds catching up with him, including his violation of federal law by running for election while still serving in the armed forces.

His campaign needed a good cause to rally support. One of the top issues of the day was the housing shortage. The construction industry was slow to respond to Americans’ desire to buy a home in the suburbs.

The other issue was communism. Americans had long regarded the communist regime in the Soviet Union with mistrust and fear. No longer allies, the U.S.S.R. and America were entering a long cold war. Nations in eastern Europe were falling under Soviet domination, and the U.S. learned they had stolen our atomic bomb secrets.

Americans wondered why their country seemed to be falling behind the Soviets. Some politicians, like Congressmen Martin Dies, Carroll Reece, and Joe Martin, claimed it was treason by government officials who, they believed, were covertly working for the Soviets.

Republicans won big in the 1946 elections, largely on accusations of communist sympathies among Democrats. President Harry Truman had to show he was taking communist infiltration seriously. He signed an executive order that required millions of federal workers to take a loyalty oath. After 2.5 million employees had been checked, 5,450 went before a hearing and 5,118 were cleared. Of the 332 remaining employees, 102 were fired and the rest appealed their dismissal.

Amidst this atmosphere of suspicion, Senator McCarthy was scheduled to give a Lincoln Day speech to the Republican Women’s Club in Wheeling, West Virginia, on February 9, 1950. According to Tye, he arrived with two speeches in mind; one addressing the housing shortage, the other communists in the U.S. government.

He chose the latter.

When he finished discussing the communist sympathizers in the State Department, he held aloft a piece of paper. According to the Wheeling Intelligencer of February 10, 1950, he said, “I have here in my hand a list of 205 [State Department employees] that were known to the Secretary of State as being members of the Communist Party and who nevertheless are still working and shaping the policy of the State Department.”

Tye states that, according to McCarthy’s executive secretary, there were no names. The paper, she said, was only the notes for his speech.

McCarthy was surprised at the enthusiastic response to his claims. Within a day, 33 newspapers had picked up the story of McCarthy’s list of names. Back in Washington, he repeated his charge but wouldn’t release the names. He claimed he wanted to avoid accusing any innocent parties.

What set McCarthyism apart from other demagogic tactics was this use of imaginary proof. Beginning with that list of names, McCarthy’s campaigns continually referred to confidential information that would expose communists in government — information he never fully shared.

Many reporters, as well as millions of Americans, were dazzled by McCarthy, his accusations, his crusade, and his theatrics. Few were willing to oppose his use of slander, innuendo, and baseless accusation to discredit and, in some cases, ruin men and women in government, for fear of being accused themselves.

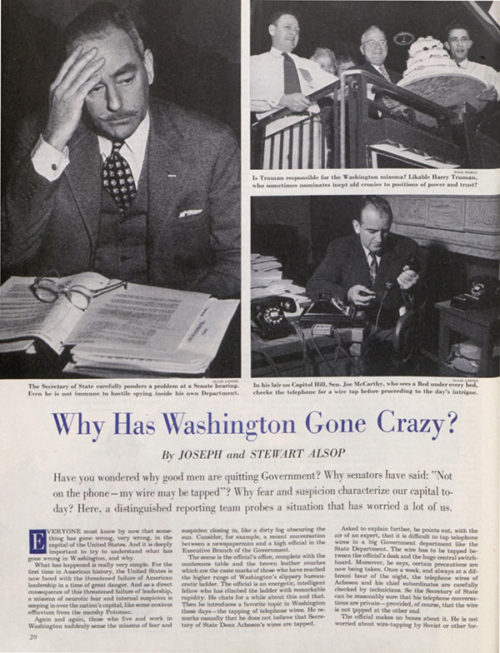

Among McCarthy’s few outspoken critics were Joseph and Stewart Alsop. On July 29, 1950, The Saturday Evening Post published their article, “Why Has Washington Gone Crazy?” They described a visit to McCarthy’s office on Capitol Hill, saying it was “like being transported to the set of one of Hollywood’s minor thrillers.

“McCarthy, despite a creeping baldness and a continual tremor which makes his head shake in a disconcerting fashion, is reasonably well cast as the Hollywood version of a strong-jawed private eye.”

Here the Alsops were hinting at the senator’s drinking problem, which would bring him to an early death.

A visitor is likely to find him with his heavy shoulders hunched forward, a telephone in his huge hands, shouting cryptic instruction to some mysterious ally. “Yeah, yeah. I can listen, but I can’t talk. Get me? Yeah? You really got the goods on the guy?”

The senator glances up to note the effect of this drama on his visitor.

“Yeah? Well, I tell you. Just mention this sort of casual to Number One, and get his reaction. Okay? Okay. I’ll contact you later.”

The drama is heightened by a significant bit of stage business. For as Senator McCarthy talks he sometimes strikes the mouthpiece of his telephone with a pencil. As Washington folklore has it, this is supposed to jar the needle off any concealed listening device.”

If the Alsops were not impressed, many voters were. They rewarded him with fanatical devotion, seeing him as the one, true American fighting communism. They made loyalty to McCarthy their principal measure of other Americans’ loyalty. Nye cites a report by pollster George Gallup: “Even if it were known that McCarthy had killed five innocent children, they would probably go along with him.” At one point, McCarthy was receiving 5,000 pieces of mail every day from supporters, many enclosing generous donations to his cause.

McCarthy could succeed in 20th century America because he claimed to have solid, specific evidence that would place statesmen or politicians at the heart of a vast conspiracy.

Not only could McCarthy make his case from minimal or nonexistent evidence, he could even use the lack of evidence to prove his point. If someone testified before McCarthy’s Permanent Subcommittee on Investigation and refused to answer on the grounds of possible self-incrimination, McCarthy used this non-answer as evidence of the witness’s guilt.

McCarthy had many foes within Washington who pressed him to present his proof of treachery before Congress. McCarthy would always deflect the request, or respond with another accusation. Ultimately this proved his undoing.

In 1954, McCarthy was accusing the U.S. Army of harboring communists. A lawyer representing the army, Joseph Nye Welch, demanded to see the names of 130 communist or subversive workers that McCarthy claimed worked in defense plants, and he wanted it “before sundown.” McCarthy responded by slandering a young lawyer in Welch’s legal firm.

Welch couldn’t believe that McCarthy would assassinate the character of a promising attorney simply to deflect the demand. It was at this moment that Welch declared his famous rejoinder, “Let us not assassinate this lad further, Senator. You’ve done enough. Have you no sense of decency, sir, at long last? Have you left no sense of decency?”

Joseph McCarthy and Joseph Welch exchange words as Welch testifies before McCarthy’s Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations (uploaded to YouTube by AmericanExperiencePBS)

Welch told McCarthy that he would no longer discuss the matter and would not respond to McCarthy’s probing. “If there is a God in Heaven it will do neither you nor your cause any good.” He asked for the next witness and the audience broke into applause.

That same month, when Wyoming Senator Lester Hunt was working to curtail McCarthy’s powers, McCarthy threatened to expose the sex-crime arrest of his son. The Wyoming senator committed suicide.

The two incidents provided the evidence that the Senate could use against him. He was censured in December for abusing his power. A broken man, he died a few months after completing his term.

There was never a question that Soviet spies existed in America. But no solid evidence ever emerged that the treachery was what or where McCarthy claimed.

McCarthyism’s goal was never to root out Soviet agents in government. Rather, it was, as President Truman said, an issue of control, which Truman opposed. He had given in on the call to hunt communist employees in the government, but now he said, “I’m going to tell you how we’re not going to fight communism… We’re not going to try to control what our people read and say and think. In short, we’re not going to end democracy.”

And McCarthyism was never simply about one man. Said journalist Edward R. Murrow, “No man can terrorize a whole nation unless we are his accomplices.”

Featured image: Chief Senate Counsel representing the United States Army Joseph Welch (left) and Senator Joe McCarthy (right), at the Senate Subcommittee on Investigations’ McCarthy-Army hearings, June 9, 1954. (Wikimedia Commons)

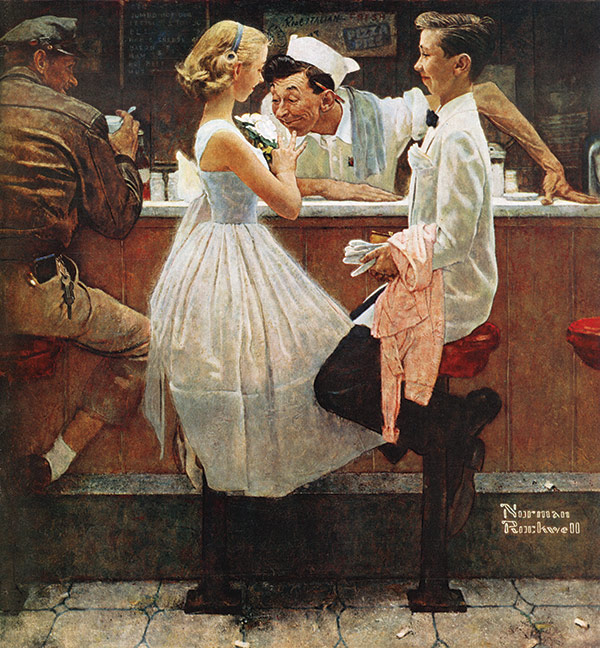

Rockwell Files: After the Prom

Rockwell freely admitted he painted “life as I would like it to be.” But in the case of this cover painting from May 25, 1957, it was no simple matter. It took a masterful sense of staging, lighting, and careful execution to share with viewers his sense of an idealized world.

He starts with the happiness of two young people as they enjoy a night of feeling “grown up.” He emphasizes the magic of the evening by contrasting them against the mundane world of a dingy truck stop.

He draws attention to their youth and innocence by dressing both in gleaming white. And he sets them beneath a beam of light from above that illuminates them and the appreciative cook. They are undisturbed by other customers, and even though Rockwell puts a dirty floor beneath them, they seem set apart from the dark interior in this perfect moment. Rockwell even echoes the viewer’s reaction by adding a bemused truck-driving spectator. Like him, we might observe this unforgettable moment with a smile of recognition, and perhaps recollections of our own.

This article is featured in the January/February 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Norman Rockwell / SEPS

When Elvis Flopped in Vegas

In a town addicted to building things, blowing them up, and then building them all over again, the New Frontier Hotel in 1955 was a fine example of Las Vegas progress. It was originally built in 1942 and called the Last Frontier, the second resort to open on what would become known as the Las Vegas Strip. Like its predecessor, El Rancho Vegas, the Last Frontier was a luxury resort in old Western garb — “The Early West in Modern Splendor,” as its promotional slogan put it.

But as ever more modern and luxurious hotels opened along the Strip, the Last Frontier decided it was time for an update, and in early 1955 the hotel closed down, gave itself a makeover, and reopened as the New Frontier. The old Western-themed showroom was transformed into the spiffy new thousand-seat Venus Room, with five tiered rows of booths and an expansive stage, “with sides running to such length that the whole thing looks like a gigantic cinemascope screen,” in the words of one awed reporter.

The hotel’s grand reopening in April 1955 was something of a disaster. Mario Lanza, the internationally renowned opera singer and movie star, was booked as the opening headliner, but he suffered a meltdown before the show — an attack of stage fright compounded by drinking — and never set foot onstage. After an hour’s delay, the hotel announced that Lanza had laryngitis, and Jimmy Durante appeared as a last-minute replacement. (Too last-minute for Las Vegas Sun columnist Ralph Pearl, who filed his review early to make his deadline and raved about Lanza’s phantom performance. “Seldom in the history of this town,” he wrote, “has a star done a greater show or received a greater standing ovation.”)

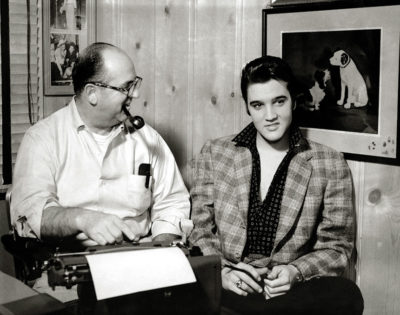

One year later the New Frontier played host to the Las Vegas debut of another, very different performer. He was nervous, too, but he did show up — though many in the audience were probably mystified as to what he was doing there. On April 23, 1956, Elvis Presley came to town.

The 21-year-old rockabilly sensation from Memphis was in the midst of his phenomenal breakthrough year. Elvis Aron Presley recorded his first RCA single, “Heartbreak Hotel,” in January. By April he had the No. 1 record in America; his gyrating TV appearances, on Tommy Dorsey’s variety show and The Milton Berle Show, were the talk of the country; and Paramount Pictures had signed him to a movie contract.

“No check is any good,” said Elvis’s manager Colonel Tom Parker. “They’re testing an atom bomb out there in the desert. What if someone pushed the wrong button?”

Elvis appearing in Vegas was his manager Colonel Tom Parker’s idea, and not a very good one. Elvis’s frenetic rock ’n’ roll performances, which were causing such a sensation in the rest of the country, were hardly geared for a crowd of middle-aged Vegas showgoers. Yet there he was at the New Frontier, touted as “The Atomic-Powered Singer” (in a town where people could watch real atomic tests taking place in the Nevada desert nearby), the “extra added attraction” on a bill headed by Freddy Martin’s orchestra and comedian Shecky Greene. Elvis got paid $15,000 for the two-week gig, and the Colonel asked for it in cash. “No check is any good,” he said. “They’re testing an atom bomb out there in the desert. What if someone pushed the wrong button?”

The audience at the New Frontier must have thought someone had pushed the wrong button. Freddy Martin, whose “sweet music” orchestra was known for its pop versions of classics like Tchaikovsky’s Concerto in B-flat, opened the show with several of his instrumental hits and a medley of songs from the musical Oklahoma! Next came Shecky Greene, a Chicago-born comedian just gaining notoriety for his raucous Vegas lounge act. Elvis was the closing act. Backed by his three-piece rhythm group — guitarist Scotty Moore, bassist Bill Black, and drummer D.J. Fontana — Elvis performed four songs and was onstage for just 12 minutes. The response was polite at best. One high roller sitting at ringside, according to a witness, got up midway through the show, cried “What is all this yelling and noise?” and fled to the casino. The critics weren’t much kinder. “Elvis Presley, coming in on a wing of advance hoopla, doesn’t hit the mark here,” wrote Bill Willard in Variety. “The loud braying of the tunes which rocketed him to the big time is wearing, and the applause comes back edged with a polite sound. For the teenagers, he’s a whiz; for the average Vegas spender, a fizz.” Newsweek said the young rock ’n’ roller was “like a jug of corn liquor at a champagne party.”

For Elvis and his backup group, accustomed to the pandemonium they were causing in concerts across the country, the response was sobering. “For the first time in months we could hear ourselves when we played out of tune,” said Bill Black. “They weren’t my kind of audience,” Elvis would say later. “It was strictly an adult audience. The first night especially I was absolutely scared stiff.”

Shecky Greene got friendly with Elvis during the run and could see that the kid was out of his element — unable to relate to the audience and lacking the stage experience to win them over. He didn’t even dress right. “He came out in a dirty baseball jacket, just shit,” Greene recalled. “I went to Parker and I said, you can’t let him come out on the stage like that.” The Colonel apparently took Greene’s advice; for the rest of the engagement, Elvis and his band wore neat sport jackets, slacks, and bow ties. But after the first night, they no longer closed the show. Shecky Greene did.

By happy chance, a recording of Elvis’s 1956 Vegas show exists — taped by an audience member on the last night of the two-week engagement. Freddy Martin makes a polite, if rather patronizing, introduction, noting that it’s Elvis’s last performance: “We hate to see him go; he’s a fine young lad and a fine talent.” Elvis opens his set with “Heartbreak Hotel” — slower and bluesier than the recorded version, with Elvis playfully changing the lyric to “Heartburn Motel” in the last verse. His patter with the audience is disarmingly modest; Elvis is acutely aware that he’s a fish out of water. “We’ve got a few little songs we’d like to do for you,” he says at the outset, “in our style of singing — if you want to call it singing.” He alludes to the difficulties he’s been having in the engagement: “It’s really been a pleasure being in Las Vegas. We had a pretty hard time — uh, a pretty good time. …” He makes a few awkward, country-boy jokes, asking the orchestra at one point if they know his next song, “Get Out of the Stables, Grandma, You’re Too Old to Be Horsin’ Around.” After three more numbers — “Long Tall Sally,” “Blue Suede Shoes,” and “Money Honey” — it’s over.

Elvis’s only chance to connect with his real audience came on a special Saturday matinee, scheduled by the hotel expressly for the teenagers who weren’t allowed into the casino for the evening shows. For a $1 admission (the proceeds donated to a local Little League baseball program), the kids got a free soft drink and a chance to shower Elvis with the kind of screaming adulation he was getting almost everywhere but in Las Vegas.

“The carnage was terrific,” reported Bob Johnson in the Memphis Press-Scimitar. “They pushed and shoved to get into the 1,000-seat room and several hundred thwarted youngsters buzzed like angry hornets outside. After the show, bedlam! A laughing, shouting, idolatrous mob swarmed him; he fled to the insufficient sanctuary of his suite. The door wouldn’t hold them out. They got his shirt, shredded it. A triumphant girl seized a button, clutched it as though it were a diamond. A squadron of police had to be called in to clear the area.”

The door wouldn’t hold them out. They got his shirt, shredded it. A triumphant girl seized a button, clutched it as though it were a diamond.

A few of the old-timers in Vegas tried to get hip to the new music phenom. “This cat, Presley, is neat, well gassed and has the heart,” wrote Ed Jameson in a tongue-in-cheek column for the Las Vegas Sun titled “A Cat Talks Back.” “His vocal is real and he has yet to go for an open field. He is hep to the motion of sound with a retort that is tremendous. These squares who like to detract their imagined misvalues can only size a note creeping upstairs after dark. This cat can throw ’em downstairs or even out the window. He has it.”

Though it was a tough engagement for him, Elvis enjoyed Las Vegas. He didn’t gamble much, but he checked out other entertainers in town (among them Johnny Ray, the Four Aces, and Liberace), went to the movies, and rode the bumper cars at the Last Frontier Village next door. He kept company with Judy Spreckels, a sugarcane heiress from Los Angeles, and Vampira, the campy TV horror-show host who was appearing in Liberace’s show at the Riviera. An Elvis fan from Albuquerque, Nancy Kozikowski, was on a vacation in Las Vegas with her parents and ran into Elvis several times during her stay — in the hotel lobby, at the restaurant, and one afternoon when he was wandering alone at the Last Frontier Village. “He recognized me and was very nice,” she recalled. “We took pictures in the 25-cent picture booth together and alone. We also made a very funny talking record together. … Elvis was very nice, very gentle, a perfect gentleman.”

Elvis’s first visit to Las Vegas had one unexpected by-product. Among the lounge acts Elvis went to see was Freddie Bell and the Bellboys, a sextet from Philadelphia that did a kind of slicked-up, finger-snapping, nightclub-friendly version of early rock ’n’ roll. (The group had a bit role in the movie Rock Around the Clock, which had just opened in theaters.) One of the highlights of their show was an up-tempo version of “Hound Dog,” a blues number that had been a hit in 1953 for Willie Mae (“Big Mama”) Thornton. Elvis was so taken with Bell’s performance that he began doing the song in his own act and recorded it later that summer. “Hound Dog” became Elvis’s fastest-selling record yet, and his signature hit.

His 1956 Las Vegas engagement is regarded by most Elvis chroniclers as a rare misstep in a year of meteoric success, otherwise orchestrated to perfection by Colonel Parker, the onetime carny promoter and manager of country star Eddy Arnold who became Elvis’s manager and career guru early that year. The Colonel would later defend the booking, saying it gave Elvis a chance to reach a new audience and pointing out that the New Frontier couldn’t have been too disappointed, since the hotel asked him back for a return engagement.

Shecky Greene — who thought Elvis was a “wonderful kid” but turned down an offer from Colonel Parker to tour with Elvis as his opening act, finding the prospect faintly absurd — never quite understood what all the fuss was about. One day he ran into Bing Crosby, who was in Vegas during Elvis’s engagement. “What is the thing about this kid?” Shecky asked the elder statesman of American pop singing. “He’s a nice kid, but …”

“Shecky,” Bing replied, “he’ll be the biggest star in show business.”

Excerpted from Elvis in Vegas: How the King Reinvented the Las Vegas Show by Richard Zoglin. Copyright © 2019 by Richard Zoglin. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Featured image: ScreenProd / Photononstop / Alamy Stock Photo