Considering History: Kamala Harris’s Heritage and the Legacies of Slavery and Sexual Violence

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

In the immediate aftermath of Joe Biden’s selection of Senator Kamala Harris to be his vice presidential running mate, a controversial Newsweek article raised questions of whether Harris, the daughter of two immigrants, would be eligible to serve in that role if elected. The article, authored by a right-wing law professor who had previously run against Harris for the position of California’s Attorney General, doesn’t hold legal water; Harris was born in Oakland and so was, from birth, a United States citizen, as guaranteed by the 14th Amendment. But the article has reignited debates over that Constitutional concept of birthright citizenship, one that President Trump has at various times expressed a desire to do away with.

While Harris’s own citizenship status under that existing law is clear and indisputable (as Newsweek has subsequently admitted), there is another, more genuinely complex part of her heritage and family that has also received renewed attention since the VP announcement. In 2018, Harris’s father Donald, a Jamaican-American immigrant and retired Stanford University economics professor, wrote an article about his Jamaican ancestors in which he argued that he is descended on his father’s side from the infamous 19th century white slave owner Hamilton Brown, who ran one of the island’s largest plantations and was responsible for the importation and enslavement of hundreds of Africans.

Donald Harris’s claims about his relationship to Hamilton Brown have been used by conservative pundits like Dinesh D’Souza and others as a “gotcha” moment, as the basis for arguments that neither Harris nor her supporters can discuss the legacies of slavery and racism since she herself is descended from a white slave owner. But in truth that heritage, which is shared by a significant number of Americans of African descent, reflects one of the most essential and too-often forgotten histories of slavery and the sexual violence that accompanied it. And if we set aside political and partisan concerns, Harris’s story can help us understand those vital histories of slavery, sexual violence, race, and heritage, the legacies of which are certainly still with us in 21st century America.

One of the most consistent and central elements of chattel slavery, as it was practiced throughout the Americas, was the rape of enslaved women by male slave owners. It is difficult if not impossible to ascertain the percentage of enslaved women who were so violated (and thus of enslaved children who were the product of such acts), both because the practice was so ubiquitous and because it was for centuries under-narrated in histories of slavery. The latter trend has been challenged in recent years, as illustrated by historian Rachel Feinstein’s When Rape Was Legal: The Untold History of Sexual Violence During Slavery (2019) among other works.

Another recent trend that has made it more possible to grapple with these histories is the rise of ancestry studies and the corresponding use of DNA analysis to trace heritages. For example, the scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr., a pioneer in the use of such data to analyze individual, familial, and collective ancestries, estimates that “a whopping 35 percent of all African-American men descend from a white male ancestor who fathered a mulatto child sometime in the slavery era, most probably from rape or coerced sexuality.” And since that number reflects 21st century identities and all the other factors that have contributed to them, it likely only scratches the surface of how widespread these practices and their effects were in the era of slavery.

While many of those experiences are unfortunately lost to history, individual case studies can help us engage with the aftermath of sexual violence under slavery. As I highlighted in this July 4th column, the story of Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings offers one particularly prominent such case study. After nearly two centuries of rumors and debate, both DNA analysis and the pioneering work of scholar Annette Gordon-Reed have confirmed that Jefferson did rape and father at least one child (and almost certainly six or more children) with Hemings, one of the enslaved women on his Monticello plantation. Historians have only begun to uncover the complex stories of the descendants of those sexual assaults, enslaved young men and women who, despite their famous father and the promise of freedom that came with that status, still experienced some of the worst of antebellum American slavery and racism.

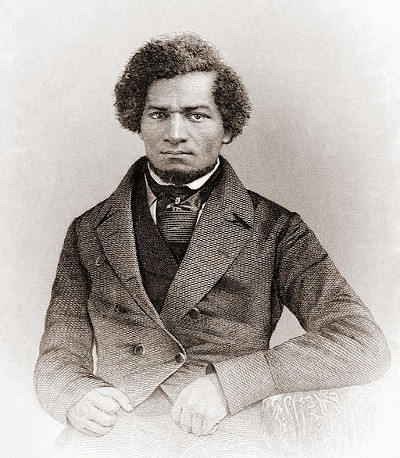

Another of the 19th century’s most famous Americans, Frederick Douglass, experienced life as the child of sexual assault under slavery. In the opening chapter of his 1845 Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Douglass notes his belief that his father, whom he never knew, was the white slave owner of the Maryland plantation onto which he was born. As usual with his autoethnographic works, Douglass uses this personal detail to illuminate social and historical meanings, noting for example that the law making the children of enslaved women themselves slaves “is done too obviously to administer to [slaveowners’] own lusts, and make a gratification of their wicked desires profitable as well as pleasurable; for by this cunning arrangement, the slaveholder, in cases not a few, sustains to his slaves the double relation of master and father.” But Douglass also empathetically notes the potentially painful effects for all involved, from masters having to sell their own children to “one white son” having to “ply the gory lash to his [brother’s] naked back.”

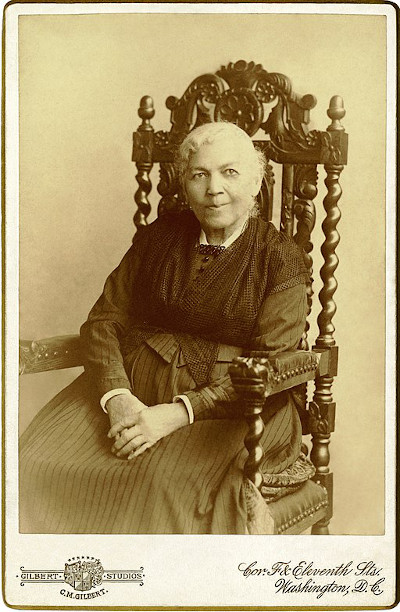

Douglass did not have the chance to know his mother well before her tragic death, so he was unable to write about her perspective. But another prominent personal narrative of slavery, Harriet Jacobs’ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861), captures the experience of enslaved women under the constant threat of sexual violence. As Jacobs puts it in her chapter “The Trials of Girlhood,” “there is no shadow of law to protect her from insult, from violence, or even from death; all these are inflicted by fiends who bear the shape of men…She will become prematurely knowing in evil things. Soon she will learn to tremble when she hears her master’s footfall. She will be compelled to realize that she is no longer a child.” And through her own constant battles with her despicable master Dr. Flint, Jacobs traces how “the influences of slavery had the same effect on me that they had on other young girls; they had made me prematurely knowing, concerning the evil ways of the world.”

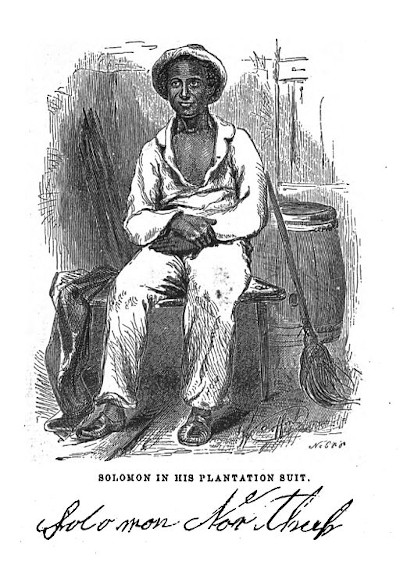

Individuals like Douglass and Jacobs managed to escape the horrors of slavery and publish their stories. But of course the vast majority of both enslaved women raped by their owners and the children of those rapes remained enslaved throughout their lives. We get a glimpse of such experiences in another personal narrative, Solomon Northrup’s Twelve Years a Slave (1853). At the final plantation to which Northrup is taken, he meets Patsey, an enslaved young woman whose beauty and strong will make her a singular focus of her owner Edwin Epps. If not enslaved, Northrup writes, Patsey “would have been chief among ten thousand of her people”; but on the Epps plantation, this impressive young woman becomes instead “the enslaved victim of lust and hate,” with “no comfort in her life.” Although the illegally kidnapped Northup is eventually rescued from the Epps plantation, he can do nothing for Patsey; a tragic reality captured in a culminating scene from the 2012 film adaptation of 12 Years, as Northup (Chiwetel Ejiofor) watches Patsey (Lupita Nyong’o) recede as he rides away from the plantation.

No one can blame Northup in this moment, as there is nothing he can do for Patsey. But for far too long, both our laws and our collective memories likewise abandoned enslaved women like Patsey and their children to sexual violence and its effects. We cannot change the past, but—with heritages like Kamala Harris’s to help guide us—we can remember those histories and consider all that they mean for all Americans.

Featured image: Kim Wilson / Shutterstock

Review: A Most Beautiful Thing — Movies for the Rest of Us with Bill Newcott

A Most Beautiful Thing

⭐ ⭐ ⭐ ⭐

Run Time: 1 hour 35 minutes

Narrator: Common

Director: Mary Mazzio

Now streaming on XFinity VOD; on Peacock September 1; on Amazon Prime October 14.

The best documentaries lull you into thinking they’re taking you for a nice float on a lazy stream — then abruptly suck you into a chasm of Class 5 rapids that have you holding on for dear life.

That’s the kind of ride we get in director Mary Mazzio’s new film, which starts out as the inspiring tale of America’s first all-African-American public high school rowing team — but has much more on its mind than warm feelies.

It’s the 1990s on the West Side of Chicago, where gang violence is tearing apart the student body of Manley High School. Enter a white Chicago businessman named Ken Alpart, who naively convinces administrators that what the school really needs is a rowing team. He puts a sleek crew shell on display in the cafeteria, offers free pizza to anyone who signs up — and waits to see who comes through the door.

What he gets is a random collection of rival gang members, kids barely holding onto their lives, much less their grades. We meet them in the present day: Grown men, now nearly 40, scarred by their harrowing youths. Foremost among them is Arshay Cooper, who recalls for us his daily adventure walking five blocks to school — and having to wear his baseball cap a different way each block, so as not to get jumped by the local street gang.

The guys laugh as they recall their first time sitting in the low, easily-tipped boat — terrified they might end up in the water.

Some were ready to quit before they got started until, as Cooper recalls, he asked them, “How can you deal with gunshots all day long in your neighborhood and you’re scared to sit in a boat?”

From here the narrative seems to be going just as we’ve hoped: On the water, the guys find a peace they’ve never known before. The former sworn enemies become a team. They enter their first competition, fail miserably, but learn from their mistakes. Finally, at the biggest race of the year, they not only earn the respect of other rowers, but they are celebrated by the entire city of Chicago.

It’s an engaging, feel-good story that seems tailor made for a Hollywood remake — you could probably do the casting yourself.

But something seems a little off here: We’re barely halfway through the film’s run time, and the kids are already graduating from high school. They say farewell to their rowing adventure. Everyone goes their separate ways.

Now what?

It is now 2018, and the old teammates have just learned that an assistant coach from their high school days has suddenly died. They gather for the funeral, and Cooper hatches an audacious plan: Why not have a reunion row? It doesn’t take long for everyone to get on board with the idea.

It’s a decision that makes the second half of A Most Beautiful Thing even more inspiring than the first. For one thing, virtually none of the guys is anywhere near rowing shape. For another, it goes without saying none of the kids went on to Ivy League rowing glory; they returned to the ’hood where the familiar litany of misfortune awaited many of them: drugs, crime, poverty, and imprisonment. Skillfully and respectfully, Mazzio unfolds each man’s history, exploring the inner city dynamics that stacked the deck against them from the start (she cites a study that reports children from neighborhoods like these suffer higher rates of PTSD than combat soldiers).

Still, after a rocky start, the old teammates rediscover their rhythm. Cooper — who wrote the book on which this film is based, is a sought-after motivational speaker and has become something of a legend in the rowing community — even enlists Olympic rowing coach Mike Teti to whip them into shape.

But Cooper has more than a rowing reunion in mind. Recalling how the sport brought gang rivals together, he hatches an outrageous notion: Why not invite four members of the Chicago Police Department to row with them?

Now, Mazzio has just spent the last hour or so illustrating the tortured relationship between the cops and the ’hood. At this very moment, one of the guys is wearing an ankle bracelet after a run-in with the law. But they trust Cooper and reluctantly agree, leading to some of the most remarkable scenes of awkwardly effective bridge building you’ll ever see.

Finally, the team decides to enter one last official race, returning to the waters where they found high school glory. By now we’re beyond worrying about whether they’ll win or lose. We’re all friends here.

It’s hard to imagine a more stormy sea than the one this country is navigating right now, but the inspiring men from Manley High School have a couple of lessons for us all: First, don’t assume that everyone who’s not on your side is your enemy. And second, it’s possible to find common cause with just about anyone, even if you have to keep them at oar’s length.

Featured image: Richard Schultz/50 Eggs Films

The First Black U.S. Senator Argued for Integration after the Civil War

Despite a days-long outcry from Democratic senators attempting to block the first African-American member of the U.S. Congress from taking his seat, Hiram Rhodes Revels was finally voted in to the Senate along party lines 150 years ago today.

Revels had been appointed to his seat by Mississippi Republicans, as senators at the time were selected by the state legislature instead of by popular vote. Revels had served as an alderman in Natchez, Mississippi, having settled there after traveling the country as a minister, educator, and chaplain for the Union army. When he arrived in Washington, D.C. to be sworn in, Revels was met with protest from the minority Democrats.

“There was not an inch of standing or sitting room in the galleries, so densely were they packed,” according to The New York Times, “and to say that the interest was intense gives but a faint idea of the feeling which prevailed throughout the entire proceeding.” An atmosphere of fervent argument erupted in the chamber in those few days of deliberation over whether or not to allow the first black senator into the body, but the Times only hints at the insulting, racist language hurled at Revels and his defenders.

The official argument used against Revels was that he had not been a U.S. citizen for the nine years required to be eligible for the U.S. Senate. Even though Revels was born a free man — in 1827 — Democratic senators argued that the Civil Rights Act of 1866 had given the Mississippi alderman only four years of citizenship. Several Republicans held that this was an absurd argument, and that the Senate ought to vote Revels in and begin a new age of representation for African Americans. Democrats accused them of “hollowness and insincerity” for the causes of black men, claiming Republicans were only looking after “partisan considerations.”

In the late afternoon, on February 25th, the vote was taken, and Democrats lost, 48 yays to 8 nays. The Times credited Revels for remaining dignified even though “the abuse which had been poured upon him and on his race during the last two days might well have shaken the nerves of anyone.” He took an oath of office, took his seat, and the Senate was adjourned for the weekend.

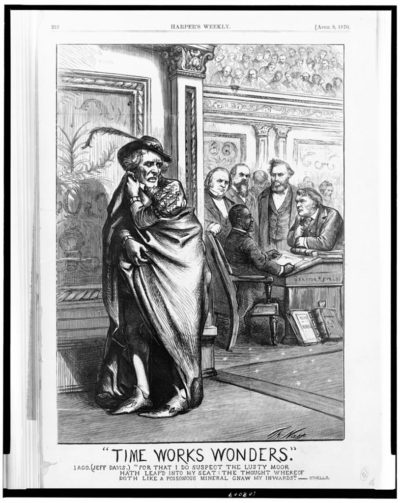

Of the two Mississippi Senate seats filled in that session, one had been most recently occupied by Jefferson Davis, the president of the Confederacy during the Civil War. Harper’s Weekly ran a political cartoon by Thomas Nast that featured Davis as Iago, the traitorous villain of Shakespeare’s Othello, looking on at Revels taking his place in the chamber: “For that I do suspect the lusty moor hath leap’d into my seat: the thought whereof doth like a poisonous mineral gnaw my inwards.”

Revels only served in the U.S. Senate for about a year. Toward the end of his term, on February 8, 1871, Revels sat on the Committee on the District of Columbia as it heard arguments over a clause that would have effectively desegregated D.C. schools. Senator Revels addressed the committee, arguing against an amendment to strike the clause, saying, “If the nation should take a step for the encouragement of this prejudice against the colored race, can they have any ground upon which to predicate a hope that Heaven will smile upon them and prosper them?” He spoke about the oppression of African Americans all over the country that continued because of segregation in housing, church, transportation, and education, and he pleaded his fellow senators to consider how desegregated schools could help to empower African Americans “without one hair upon the head of any white man being harmed.” Unfortunately, his side lost the vote, and school segregation remained lawful in Washington, D.C. until 1954.

Revels was the first in a small wave of black southern congressmen during the Reconstruction Era. A few years after his term, another African American — Blanche Bruce — was elected to the Mississippi Senate. Bruce was able to serve a full term, but Mississippi hasn’t elected an African-American U.S. senator since. In fact, only ten have served in the history of the country.

Featured image: Hiram Revels, the first African American to serve as a U.S. senator. (Library of Congress / Brady Handy Photograph Collection)

Considering History: Remembering the History of Slavery Is Both Necessary and Patriotic

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

Since its August 2019 launch, the New York Times Magazine’s 1619 Project, an initiative that examines the consequences of slavery in the United States, has received many different responses, including pushback and critique, from a wide variety of sources. But over the last few weeks, a new challenge has emerged: the Woodson Center’s 1776 Project, a collaboration between a number of African-American journalists, entrepreneurs, and academics (although it features no historians). As Woodson Center founder and 1776 Project creator Bob Woodson puts it, in a direct rebuke to the 1619 Project’s emphasis on slavery’s enduring legacy, the 1776 Project is intended to “challenge those who assert America is forever defined by past failures.” “We seek,” the project’s mission statement adds, “to offer alternative perspectives that celebrate the progress America has made on delivering her promise of equality and opportunity.”

In other words, the 1776 Project seeks to create an explicit dichotomy between remembering the histories of slavery and moving forward, arguing that focusing on those histories (the 1619 Project’s central goal) makes continuing our shared progress more difficult. The 1776 Project also strives to distinguish between criticisms of America’s past and celebrations of its promise. In this Martin Luther King Day column, I made the case for critical patriotism, which is critiquing America’s failures (past as well as present) in order to move the nation closer to its ideals. Here, I want to make a parallel case for challenging why better remembering our most horrific histories is both necessary and patriotic.

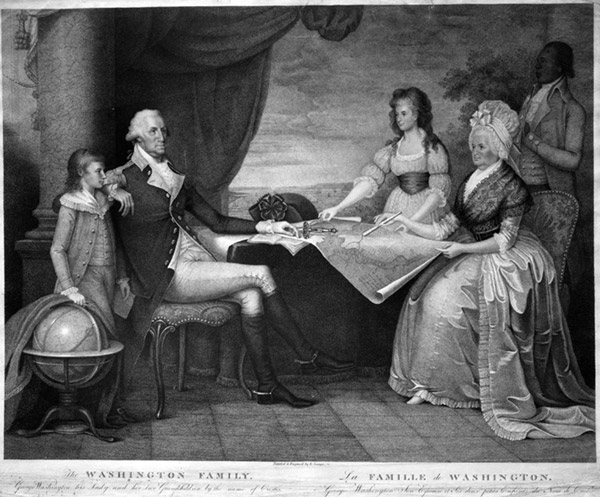

Offering a particularly striking illustration of the defining interconnections between slavery and America’s origins is Founding Father George Washington. It’s not just that Washington was a slave-owner, and thus subject to the same critiques I leveled against his peer Thomas Jefferson. Instead, it’s that in perhaps his most significant role as the nation’s first president, Washington was even more thoroughly defined by his choices within that horrific and destructive system.

Washington was inaugurated and began serving his first presidential term in New York City, the new nation’s capital, in 1789. But the July 1790 Residence Act shifted the capital to Philadelphia for the next ten years, during which time a permanent capital would be constructed in Washington, D.C. When it came to slavery, Pennsylvania was distinct from the rest of the nation, having passed the 1780 Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery, a law which, along with a 1788 Amendment, made it illegal for a non-resident slave-owner to hold slaves for longer than six months (after six months’ residency, any such enslaved people would become free). Washington argued that since he was only in the state due to his presidential role, he should not be subject to that law; but fearing that his slaves would nonetheless be freed, he devised a plan to rotate all slaves back to Virginia just before they reached that six-month threshold, keeping them all enslaved.

At least one of those enslaved African Americans directly resisted that practice, using instead the household’s Philadelphia location to escape from slavery and the Washingtons. That woman, Ona Judge, is the subject of Erica Dunbar’s magisterial book Never Caught: The Washingtons’ Relentless Pursuit of Their Runaway Slave, Ona Judge (2017). As Judge put it in an 1845 interview with the abolitionist New Hampshire newspaper The Granite Freeman, “Whilst they were packing up to go to Virginia, I was packing to go, I didn’t know where; for I knew that if I went back to Virginia, I should never get my liberty.” After Judge escaped, President Washington devoted considerable time and resources to seeking her re-capture and re-enslavement, even refusing an offer (made by Judge through intermediaries) that she would return if she were promised freedom upon the Washingtons’ death. Although she was indeed never caught, she would remain a fugitive throughout her life.

![Runaway Advertisement for Oney Judge, enslaved servant in George Washington's presidential household. The Pennsylvania Gazette, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, May 24, 1796. "Advertisement. ABSCONDED from the houshold [sic] of the President of the United States, ONEY JUDGE, a light mulatto girl, much freckled, with very black eyes and bushy black hair. She is of middle stature, slender, and delicately formed, about 20 years of age. She has many changes of good clothes of all sorts, but they are not sufficiently recollected to be described—As there was no suspicion of her going off, nor no provocation to do so, it is not easy to conjecture whither she has gone, or fully, what her design is;—but as she may attempt to escape by water, all matters of vessels are cautioned against admitting her into them, although it is probable she will attempt to pass as a free woman, and has, it is said, wherewithal to pay her passage. Ten dollars will be paid to any person who will bring her home, if taken in the city, or on board any vessel in the harbour;—and a reasonable additional sum if apprehended at, and brought from a greater distance, and in proportion to the distance. FREDERICK KITT, Steward. May 23 [illegible]."](https://www.saturdayeveningpost.com/wp-content/uploads/satevepost/2020-02-24-Oney_Judge_Runaway_Ad-wikimedia-commons.jpg)

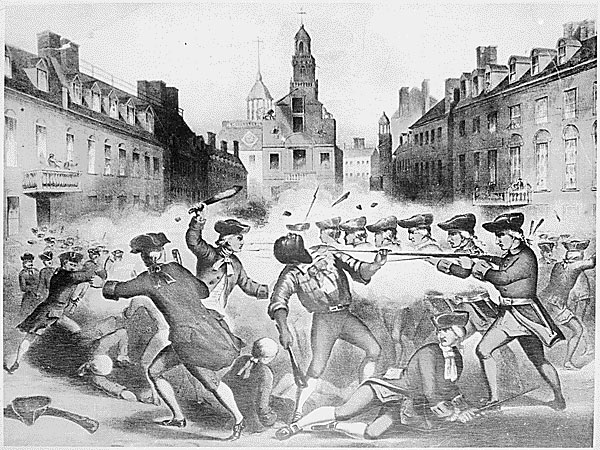

Another American who was fleeing that same system in search of those same ideals happens to be one of the most prominent individuals associated with the origins of the American Revolution and the new nation: Crispus Attucks. Attucks gained fame when he was shot and killed at the March 5, 1770, events that came to be known as the Boston Massacre. Attucks is often described as “the first casualty of the American Revolution.” As we approach the 250th anniversary of the Massacre, it’s worth noting that Attucks’s status as a fugitive slave has been much less consistently highlighted in that famous narrative of this iconic Revolutionary figure.

While some details of Attucks’s life remain hazy, others are clear and historically significant. His father was apparently an enslaved African (Prince Yonger) and his mother (Nancy Attucks) a Native American of the Natick tribe; Nancy may or may not have been enslaved as well, but in any case such a mixed-race child was defined by the colony’s laws in the era of Attucks’s 1720s birth as a “black,” and thus he was enslaved from birth on a Framingham farm. In 1750 the roughly 27-year-old Attucks ran away from slavery, which we know because his master, William Brown, placed an advertisement describing Attucks and seeking his return. Although Brown warned that “all Matters of Vessels and others, are hereby cautioned against concealing or carrying off said Servant on Penalty of Law,” Attucks not only remained a fugitive for the next 20 years but became a sailor as well as a ropemaker at Boston’s seaport.

That role and setting are certainly part of what led Attucks to King’s Street in March 1770, as many of the protesters were sailors. But how much would our narratives of Attucks as a defining member of that pre-Revolutionary protest, as “the first casualty of the American Revolution,” shift if we likewise foregrounded his status as a fugitive slave — as a man who had been born into that world, had escaped it in his quest for liberty, and faced every day after the possibility of being recaptured into that tyrannical system? And how much would our narratives of the Boston Massacre and the Revolution shift as well? At the October 1770 trial of the British soldiers charged with murder, their defense lawyer, future founder and president John Adams, critiqued Attucks’s “mad behavior,” arguing that his “very looks was [sic] enough to terrify any person.” But indeed, Attucks’s actions and identity were neither mad nor terrifying, but representative of both the worst and the best of America, at our founding moment and ever since.

Featured image: National Archives at College Park / Public domain

Considering History: “There’s Time Enough, but None to Spare” — A Black History Month Lesson in Critical Optimism

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

If you’re like me, much of the news has felt pretty close to apocalyptic for some time now, but the first month of 2020 has taken things to another level. The assassination and reprisal that pushed the U.S., Iran, and perhaps the world to the brink of war. The raging Australian wildfires that killed billions of animals, sent smoke as far away as New Zealand, and (along with the seemingly constant Puerto Rican earthquakes) foreshadowed a year of accelerating climate catastrophes. The deadly mega-virus that is sweeping China and Southeast Asia and has led the World Health Organization to declare a global emergency for only the sixth time in its history. The impeachment debates in which a prominent Republican Senator admitted in an extended Twitter thread that the president illicitly sought foreign interference in the 2020 election and illegally covered it up — and then that Senator voted not to have witnesses at the trial.

In light of all these and so many other stories, it can feel difficult, if not downright impossible, to maintain hope for the future. But there’s a corollary concept to the critical patriotism I discussed in my Martin Luther King Day column: critical optimism. This form of optimism, which I defined and advocated as part of my book History and Hope in American Literature: Models of Critical Patriotism (2016), recognizes and engages with the hardest and worst of our world, yet seeks to find reasons for hope nevertheless, not despite those realities but through and beyond them. And as we begin Black History Month, it happens that one of the most critically optimistic texts I know was authored by an African-American author and focuses on an act of racial terrorism: Charles W. Chesnutt’s The Marrow of Tradition (1901), a historical novel inspired by the horrific 1898 Wilmington (North Carolina) white supremacist coup and massacre.

Chesnutt’s life and career themselves modeled critical optimism in response to some of America’s bleakest realities. The grandson of enslaved people and son of two free African Americans who moved their family from North Carolina to Ohio just before the Civil War, Chesnutt chose to return to North Carolina after the war and work as an educator and principal during Reconstruction. Both of his grandfathers were likely white slave owners and he was light-skinned enough to be mistaken for white many times in the course of his life, but Chesnutt consistently and publicly defined himself as African American and dedicated his writing career to (as he wrote in his journals) “exalt my race.” And when editors and publishers sought to pigeon-hole his writing into the late 19th century’s “plantation tradition” genre, he both exploded that genre’s conventions (in his book of “conjure tales”) and wrote socially realistic and politically activist novels that defied such categorizations altogether.

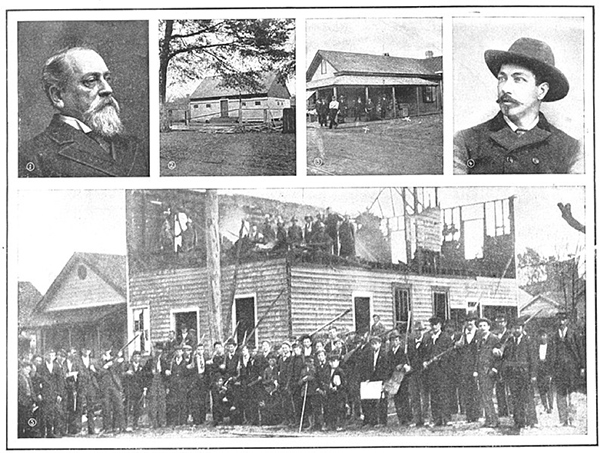

The best of those novels, and one of American culture’s most vital representations of both horrific histories and critical optimism, is The Marrow of Tradition. Chesnutt’s North Carolina roots and life were in Fayetteville, about 90 miles northwest of Wilmington, but he had many relatives and friends in the Wilmington area and knew the city well. As of 1898, Wilmington was one of the few cities in the state (and indeed throughout the South) in which the region’s resurgent white supremacists had not taken power; the city’s mayor and most other elected officials were at the time part of the Fusion Party, a progressive North Carolina political movement that brought together African Americans and radical white allies. White supremacists were frustrated by that state of affairs and angered by a newspaper editorial in which Alexander Manly, the African-American owner and editor of the Wilmington Daily Record (perhaps the only black-owned daily paper in the nation), highlighted the horrific truths of the lynching epidemic. As a result, the white supremecists spent months planning a domestic terrorist attack on the city.

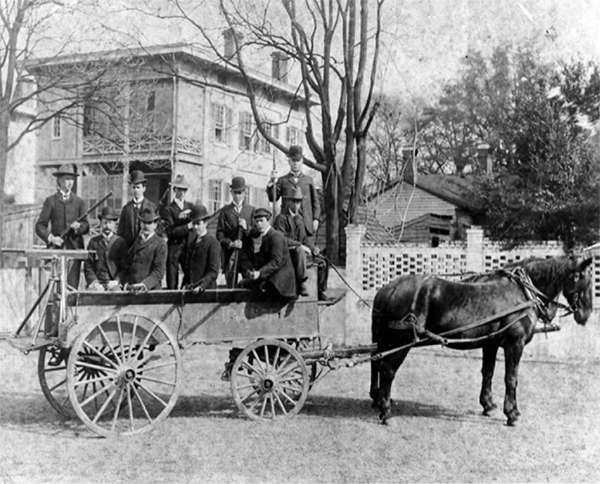

That attack unfolded on election day, November 10th, 1898. It included the only coup d’etat in American history, as the city’s elected officials were violently forced out and replaced by hand-picked white supremacist leaders. It also featured the massacre, an orgy of violence targeting the city’s African-American community. White supremacist militias traveled from around the state to take part in the attacks, bringing with them, among many other weapons, a Gatling gun that rolled through town on a cart firing indiscriminately. By the time the day was done they had burned down the Daily Record and many other buildings, killed hundreds of African-American residents and injured many more, and essentially destroyed the city’s black community for generations. The newly installed white supremacist “Revolutionary Mayor,” Alfred Waddell, would two weeks later write a story for Collier’s Magazine, designating the event a “race riot” and blaming its violence on a mythical African-American mobs and its supporters.

Both those horrific histories and that media misrepresentation inspired Charles Chesnutt to write a novel about the massacre. Set in the fictionalized city of Wellington, Chesnutt’s sweeping historical novel depicts many elements of the late 19th century South and nation, including the aftermath of slavery and the Civil War, the rise of both the KKK and Jim Crow segregation, the lynching epidemic, and life for mixed-race individuals in a society organized so thoroughly around the color line. But the novel builds to a multi-chapter depiction of the massacre and coup, a bracing portrayal that delves into the heart of that day’s violence and ends with one of the bleakest and most biting sentences in American literature. The white supremacist mob has burned down the city’s African American hospital, and Chesnutt’s narrator observes, “The flames soon completed their work, and this handsome structure, … a promise of good things for the future of the city, lay smoldering in ruins, a melancholy witness to the fact that our boasted civilization is but a thin veneer, which cracks and scales off at the first impact of primal passions.”

No line could better sum up the worst of American history, exemplified by Wilmington but present in so many moments. Yet Chesnutt does not end his novel there, and instead creates a pair of final chapters that offers an example of critical optimism in the face of these horrors. Without spoiling all of their details (this is a novel that all Americans should read, now more than ever), I will note that Chesnutt puts two of his central African-American protagonists in a position to exact a small but significant moment of justice and retribution for the day’s and their society’s brutalities, one that they have deeply personal reason to desire. Yet that deserved justice would target a white infant, innocent of all these horrors and a potent symbol of the uncertain future facing the city and the nation. And the two characters choose instead to be closer to the ideals — national, spiritual, human — that their white counterparts have so thoroughly forgotten.

As the novel closes, it seems likely but not inevitable that this moment of critical optimism will succeed, that the infant will live, that a better future than this horrific present remains possible. The novel’s final line is, “There’s time enough, but none to spare.” Here in February 2020, I can’t imagine a more important pair of lessons than those provided by Charles Chesnutt and The Marrow of Tradition: the desperate need to confront the worst of our histories, of what white supremacy has been and done and remains in America; and the equally urgent possibility of seeking a better future, not despite but through and beyond our histories. Now more than ever, we need the critical optimism of this vital American novel.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Considering History: W.E.B. Du Bois and the Urgent Lessons of History

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

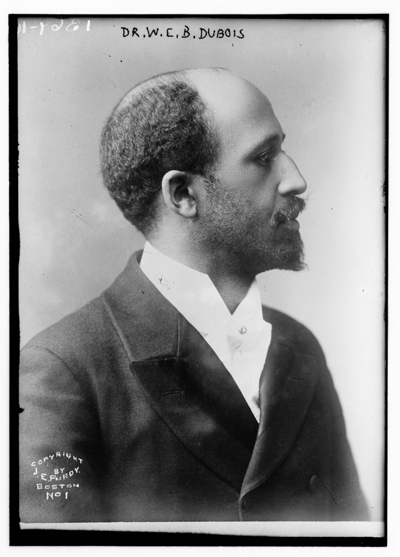

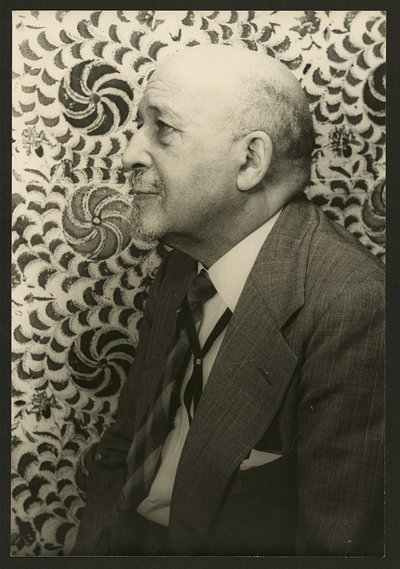

On February 23, 1868, William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts. The only child of mixed-race parents who separated when he was two, Du Bois was raised by his single mother Mary and her parents and family, experiencing this integrated community and school system as one of the town’s only African American residents. He left Great Barrington in 1885 to attend Nashville’s historically black Fisk University, and then pursued further studies at Harvard College, the University of Berlin, and back to Harvard University where he became in 1895 the first African American to receive a PhD (in History). He would spend his remaining seven decades becoming one of America’s and the world’s foremost historians, journalists, educators, writers, activists, and public figures, passing away in Ghana the day before the August 1963 March on Washington.

Those details only scratch the surface of the life, career, and impact of this towering figure, and he rewards further research and reading. But to celebrate the joint occasion of Du Bois’s 151st birthday and the last week of Black History Month, it’s worth taking a step back to consider a few of the many ways that Du Bois’s work and words resonate with our contemporary moment, offering urgent lessons for America and the world in 2019.

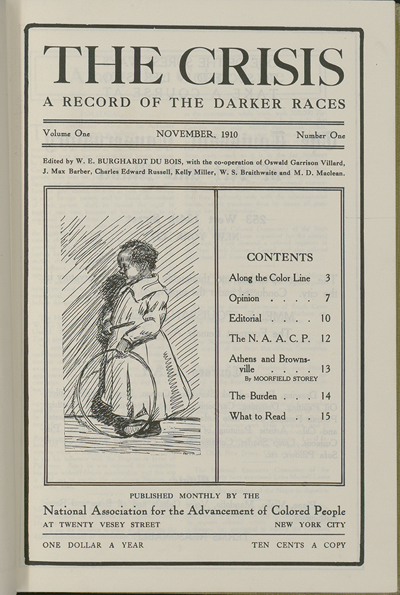

In 1910, Du Bois helped found the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and became its first director of publicity and research. In that role he founded and for many years edited the NAACP’s monthly magazine The Crisis, contributing thoughtful and impassioned editorials on many of the era’s most significant issues. In one such editorial, “Returning Soldiers” (May 1919), Du Bois highlighted the irony of African American World War I veterans returning home to face racist discrimination and violence in the U.S., and advocated for patriotic activism in response to those horrors:

But, by the God of Heaven, we are cowards and jackasses if, now that the war is over, we do not marshal every ounce of our brain and brawn to fight a sterner, longer, more unbending battle against the forces of hell in our own land. We return. We return from fighting. We return fighting. Make way for Democracy! We saved it in France, and by the Great Jehovah, we will save it in the United States of America, or know the reason why.

All too often, the antiracist protests of Colin Kaepernick, #BlackLivesMatter, and their activist peers are framed in opposition to both the military and American patriotic ideals. Yet so many moments in history, from U.S. Colored Troops during the Civil War to Jackie Robinson’s World War II sit-in for military integration, highlight the inescapable interconnections between African American activists, military service, and the nation’s highest ideals and darkest realities. Du Bois’s stirring words help us consider Kaepernick and #BLM as part of this legacy, rather than as critics of it.

In July 1930, Du Bois returned to Great Barrington to give a speech to the Searles High School Alumni Association. He chose to focus on the school’s relationship to the neighboring Housatonic River:

It may be that some thoughtful person saw far beyond the present and grasped the idea that they were putting the institution on what was the natural great highway of the valley. They may have looked forward to the time when parks and boulevards would line the redeemed river; when the best people would not attempt to climb the hills to get away from the valley, but turn about and descend to its gracious invitation; when public buildings and canoes and pleasure boats and swimming children would make the whole valley glad and the river would come into its own again. … With this beginning we may in time clear the river, give the Searles High school its perfect setting. We may even induce the mills (if we can find out who owns them) to stop pouring their refuse into the river, which is merely a habit and not a necessity. … And so I have ventured to call the attention of the graduates of the Searles High School to this bit of philosophy of living in this valley, urging that we should rescue the Housatonic and clean it as we have never in all the years thought before of cleaning it, and seek to restore its ancient beauty; making it the center of a town, of a valley, and perhaps — who knows? — of a new measure of civilized life.

While the environmental movement has evolved significantly over the last few decades, perspectives on environmental activism and justice continue to define this work as separate from our shared human communities and histories. But as Du Bois here reminds his fellow Searles graduates, the story, history, and future of our rivers (and our environment in every sense) are intertwined with those of our schools and our children, our towns and our societies. Such lessons have never been more relevant than in these pivotal remaining years to combat and reverse global climate change.

Despite these and many other diverse and deep interests, however, Du Bois was first and foremost a historian. In 1936 he published his best scholarly work, and one of the most ground-breaking and influential historiographic texts in American history: Black Reconstruction in America: An Essay Toward a History of the Part Which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860–1880. Black Reconstruction influenced both the specific scholarly conversations and the discipline of history in multiple ways, from Du Bois’s archival research process to his challenging and compelling conclusions.

But the book’s stand-out section is its last chapter, “The Propaganda of History,” where Du Bois traces the development (in educational textbooks, academic scholarship, and popular culture) of false and destructive narratives of post-Civil War history. Some of the most damning such narratives were those that depicted African Americans as so ignorant and savage that they thoroughly abused their new freedoms, as illustrated by entirely manufactured images (including a sequence in the 1915 blockbuster film Birth of a Nation) of the first African American elected officials holding raucous and lewd parties on the floors of state legislatures throughout the South. “It is propaganda like this,” Du Bois writes, “that has led men in the past to insist that history is ‘lies agreed upon’; and to point out the danger in such misinformation. It is indeed extremely doubtful if any permanent benefit comes to the world through such action. Nations reel and stagger on their way; they make hideous mistakes; they commit frightful wrongs; they do great and beautiful things. And shall we not best guide humanity by telling the truth about all this, so far as the truth is ascertainable?”

Du Bois’s thorough documentation and debunking of this propagandistic vision of post-Civil War American history is most overtly relevant to our debate over Confederate memorials and memory. Constructed in the early 20th century, the same era in which that Dunning School narrative of Reconstruction was taking hold throughout educational and cultural settings, these Confederate monuments truly represent lies agreed upon, misrepresentations of both the causes and enduring effects of the Civil War and the Confederacy. We have yet to tell the truth about their histories in our collective conversations.

Yet Du Bois’s chapter also makes the case for remembering a nation’s “great and beautiful things,” not in opposition to such dark histories but in direct relationship to them. In the final paragraphs of his magisterial book The Souls of Black Folk (1903), he highlights one such great and beautiful thing: the contribution of African Americans to every stage and element of American identity. There’s no better way to end a commemoration of Du Bois’s birthday and Black History Month than with those stirring concluding worlds: “Our song, our toil, our cheer, and warning have been given to this nation in blood-brotherhood. Are not these gifts worth the giving? Is not this work and striving? Would America have been America without her Negro people?”

Featured image: Library of Congress

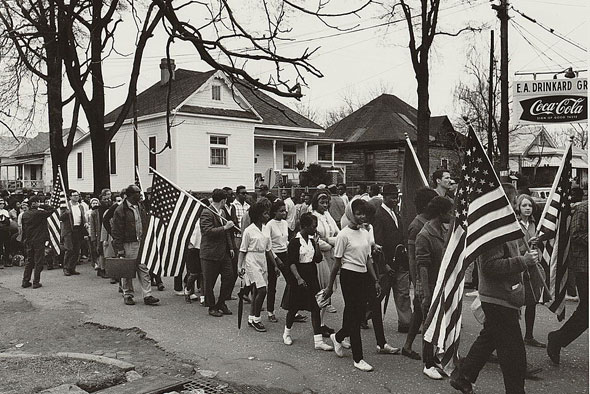

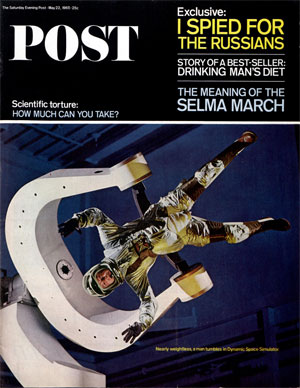

Selma and the Fight to Vote

(Image courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Last year marked a new low for voter participation in a national election. Normally, less than half of America’s voters cast ballots in the midterm elections, but the 2014 turnout was the lowest in 73 years: 36 percent. It would seem that most Americans believe their right to vote isn’t worth the effort to exercise it.

We’ve come a long way in 50 years, when Americans were ready to die just to get their names on the voter rolls — and others were willing to kill to deny them that right.

In the early 1960s, civil rights advocates traveled through the Southern states to encourage African Americans to vote. They believed the ballot would give people the power to throw out racist government officials and elect leaders who would end discrimination.

But they soon discovered that office-holders across the country had installed a number of obstacles to prevent black people from reaching the polling booths. The obstacles proved especially effective in Selma, Alabama, where only 2 percent of black residents were registered to vote.

In March 1965, activists announced they would march from Selma to Montgomery, the state capitol, and demand the state government end voter suppression. They had little hope that Governor George Wallace would change the state’s racist policy, but they knew the national attention from the march would pressure him to respond.

When marchers sets off on Sunday, March 7, the country saw how firmly some white officials opposed voting rights for black people. Sheriff’s deputies fired tear gas into the crowd, then attacked the marchers with whips and clubs. Fifty marchers were hospitalized. The marchers set out again on March 21, led by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and with protection from the National Guard and U.S. Army sent by President Johnson.

On the second day, the marchers passed through Trickem Fork, an impoverished hamlet in Lowndes County, Alabama, that represented much of what the protestors were trying to change. The Saturday Evening Post reporters W. C. Heinz and Bard Lindeman noted, “The Negroes outnumber the whites almost four to one, but until the week before the Freedom March not one Negro voter had been registered in Lowndes County in 65 years.” (“The Meaning of the Selma March: Great Day at Trickem Fork,” May 22, 1965)

Several residents had recently tried to register at the county office. White officials turned them back, saying one of their registrars was sick and they didn’t know where the other one was. Two weeks later, when the residents returned, county officials told them to register at the old jailhouse. One of the residents said, “They had the two tables set up in this room with the gallows on the left. While you’re filling out the paper, one white man is saying. ‘I guess many a guy dropped through there.’ Then another is saying, ‘I wonder if the old thing still works.’”

Another resident, an Army veteran, was told he needed to pass a literacy test. “They gave me hard questions. The first was: ‘What part does the Vice President play in the Senate and the House?’ The second was: ‘What legal and legislative steps would the State of Alabama and the State of Mississippi have to take to combine into one state?’”

Literacy tests were the last resort for state officials who wanted to deny African Americans their right to vote. Ever since Reconstruction ended in the 1870s and federal troops left the South, many white politicians sought to limit black people’s voting. In Mississippi, black voters’ names were removed from the registration polls, then required them to pay poll taxes for two years before they’d be allowed to cast ballots.

African Americans who still expressed an intention to vote might be threatened with losing their jobs. And some cities distributed fliers telling black voters they could not enter a polling station if they’d had any trouble with the law — even something as trivial as a parking ticket — unless they first got approval from their local sheriff.

(Image courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Black voters were denied credit, threatened with eviction or even lynching. If nothing else stopped these voters, there was always the literacy test. White county clerks were allowed to refuse to register anyone they considered “illiterate.”

They might require black registrants to read, and explain, complex passages of state law.* In Alabama, they would ask prospective voters questions about Federal law, as in these examples:

Has the following part of the U.S. Constitution been changed? “Representatives shall be apportioned among the several states according to their respective numbers, counting the whole number of persons in each states, excluding Indians not taxed. (No)

Who pays members of Congress for their services, their home states or the United States? (United States)

At what time of day on January 20 each four years does the term of the president of the United States end? (12 noon)

If a bill is passed by Congress and the President refuses to sign it and does not send it back to Congress in session within the specified period of time, is the bill defeated or does it become law? (It becomes law unless Congress adjourns before the expiration of 10 days.)

The literacy-test questions in Louisiana were more like brain-teasers problems, deliberately phrased to confuse the prospective voters.

In the space below, write the word “noise” backwards and place a dot over what would be its second letter should it have been written forward.

Draw in the space below, a square with a triangle in it, and within that same triangle draw a circle with a black dot in it.

Spell backwards, forwards.

Draw a figure that is square in shape. Divide it in half by drawing a straight line from its northeast corner to its southwest corner, and then divide it once more by drawing a broken line from the middle of its western side to the middle of its eastern side.

Divide a vertical line in two equal parts by bisecting it with a curved horizontal line that is only straight at its spot bisection of the vertical.

As questions on a cocktail napkin, they might have been amusing. But black citizens were required to answer 30 of these questions in 10 minutes without mistakes before they could register to vote.

The insolence of racist government policies may seem extraordinary to us today. Even more extraordinary was the determination of African Americans to overcome these challenges. They were helped in some areas by civil rights activists like members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, who taught them how to beat the trick questions. But these efforts couldn’t have succeeded if the men and women in places like Trickem Fork weren’t determined to overcome the challenges that lay between them and their right to vote.

So it seems surprising that, within the lifetime of the baby boom generation, the right to vote has become so little valued that almost 50 percent of Americans never vote in any major election.