Considering History: Remembering the History of Slavery Is Both Necessary and Patriotic

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

Since its August 2019 launch, the New York Times Magazine’s 1619 Project, an initiative that examines the consequences of slavery in the United States, has received many different responses, including pushback and critique, from a wide variety of sources. But over the last few weeks, a new challenge has emerged: the Woodson Center’s 1776 Project, a collaboration between a number of African-American journalists, entrepreneurs, and academics (although it features no historians). As Woodson Center founder and 1776 Project creator Bob Woodson puts it, in a direct rebuke to the 1619 Project’s emphasis on slavery’s enduring legacy, the 1776 Project is intended to “challenge those who assert America is forever defined by past failures.” “We seek,” the project’s mission statement adds, “to offer alternative perspectives that celebrate the progress America has made on delivering her promise of equality and opportunity.”

In other words, the 1776 Project seeks to create an explicit dichotomy between remembering the histories of slavery and moving forward, arguing that focusing on those histories (the 1619 Project’s central goal) makes continuing our shared progress more difficult. The 1776 Project also strives to distinguish between criticisms of America’s past and celebrations of its promise. In this Martin Luther King Day column, I made the case for critical patriotism, which is critiquing America’s failures (past as well as present) in order to move the nation closer to its ideals. Here, I want to make a parallel case for challenging why better remembering our most horrific histories is both necessary and patriotic.

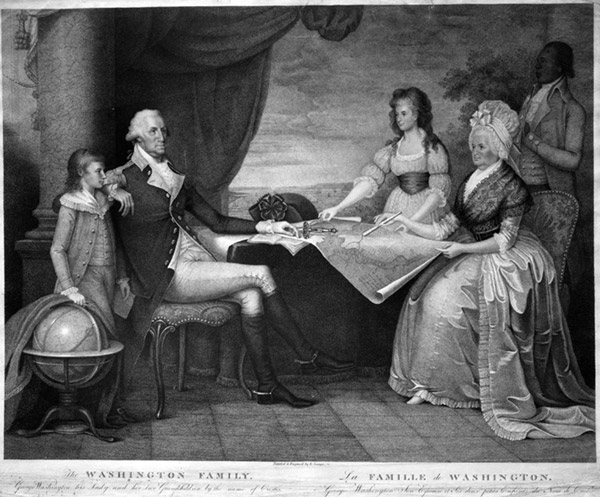

Offering a particularly striking illustration of the defining interconnections between slavery and America’s origins is Founding Father George Washington. It’s not just that Washington was a slave-owner, and thus subject to the same critiques I leveled against his peer Thomas Jefferson. Instead, it’s that in perhaps his most significant role as the nation’s first president, Washington was even more thoroughly defined by his choices within that horrific and destructive system.

Washington was inaugurated and began serving his first presidential term in New York City, the new nation’s capital, in 1789. But the July 1790 Residence Act shifted the capital to Philadelphia for the next ten years, during which time a permanent capital would be constructed in Washington, D.C. When it came to slavery, Pennsylvania was distinct from the rest of the nation, having passed the 1780 Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery, a law which, along with a 1788 Amendment, made it illegal for a non-resident slave-owner to hold slaves for longer than six months (after six months’ residency, any such enslaved people would become free). Washington argued that since he was only in the state due to his presidential role, he should not be subject to that law; but fearing that his slaves would nonetheless be freed, he devised a plan to rotate all slaves back to Virginia just before they reached that six-month threshold, keeping them all enslaved.

At least one of those enslaved African Americans directly resisted that practice, using instead the household’s Philadelphia location to escape from slavery and the Washingtons. That woman, Ona Judge, is the subject of Erica Dunbar’s magisterial book Never Caught: The Washingtons’ Relentless Pursuit of Their Runaway Slave, Ona Judge (2017). As Judge put it in an 1845 interview with the abolitionist New Hampshire newspaper The Granite Freeman, “Whilst they were packing up to go to Virginia, I was packing to go, I didn’t know where; for I knew that if I went back to Virginia, I should never get my liberty.” After Judge escaped, President Washington devoted considerable time and resources to seeking her re-capture and re-enslavement, even refusing an offer (made by Judge through intermediaries) that she would return if she were promised freedom upon the Washingtons’ death. Although she was indeed never caught, she would remain a fugitive throughout her life.

![Runaway Advertisement for Oney Judge, enslaved servant in George Washington's presidential household. The Pennsylvania Gazette, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, May 24, 1796. "Advertisement. ABSCONDED from the houshold [sic] of the President of the United States, ONEY JUDGE, a light mulatto girl, much freckled, with very black eyes and bushy black hair. She is of middle stature, slender, and delicately formed, about 20 years of age. She has many changes of good clothes of all sorts, but they are not sufficiently recollected to be described—As there was no suspicion of her going off, nor no provocation to do so, it is not easy to conjecture whither she has gone, or fully, what her design is;—but as she may attempt to escape by water, all matters of vessels are cautioned against admitting her into them, although it is probable she will attempt to pass as a free woman, and has, it is said, wherewithal to pay her passage. Ten dollars will be paid to any person who will bring her home, if taken in the city, or on board any vessel in the harbour;—and a reasonable additional sum if apprehended at, and brought from a greater distance, and in proportion to the distance. FREDERICK KITT, Steward. May 23 [illegible]."](https://www.saturdayeveningpost.com/wp-content/uploads/satevepost/2020-02-24-Oney_Judge_Runaway_Ad-wikimedia-commons.jpg)

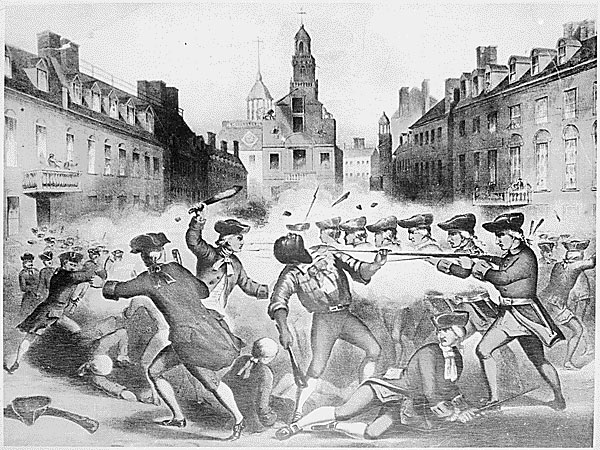

Another American who was fleeing that same system in search of those same ideals happens to be one of the most prominent individuals associated with the origins of the American Revolution and the new nation: Crispus Attucks. Attucks gained fame when he was shot and killed at the March 5, 1770, events that came to be known as the Boston Massacre. Attucks is often described as “the first casualty of the American Revolution.” As we approach the 250th anniversary of the Massacre, it’s worth noting that Attucks’s status as a fugitive slave has been much less consistently highlighted in that famous narrative of this iconic Revolutionary figure.

While some details of Attucks’s life remain hazy, others are clear and historically significant. His father was apparently an enslaved African (Prince Yonger) and his mother (Nancy Attucks) a Native American of the Natick tribe; Nancy may or may not have been enslaved as well, but in any case such a mixed-race child was defined by the colony’s laws in the era of Attucks’s 1720s birth as a “black,” and thus he was enslaved from birth on a Framingham farm. In 1750 the roughly 27-year-old Attucks ran away from slavery, which we know because his master, William Brown, placed an advertisement describing Attucks and seeking his return. Although Brown warned that “all Matters of Vessels and others, are hereby cautioned against concealing or carrying off said Servant on Penalty of Law,” Attucks not only remained a fugitive for the next 20 years but became a sailor as well as a ropemaker at Boston’s seaport.

That role and setting are certainly part of what led Attucks to King’s Street in March 1770, as many of the protesters were sailors. But how much would our narratives of Attucks as a defining member of that pre-Revolutionary protest, as “the first casualty of the American Revolution,” shift if we likewise foregrounded his status as a fugitive slave — as a man who had been born into that world, had escaped it in his quest for liberty, and faced every day after the possibility of being recaptured into that tyrannical system? And how much would our narratives of the Boston Massacre and the Revolution shift as well? At the October 1770 trial of the British soldiers charged with murder, their defense lawyer, future founder and president John Adams, critiqued Attucks’s “mad behavior,” arguing that his “very looks was [sic] enough to terrify any person.” But indeed, Attucks’s actions and identity were neither mad nor terrifying, but representative of both the worst and the best of America, at our founding moment and ever since.

Featured image: National Archives at College Park / Public domain

Considering History: Guns, the Constitution, and Our 21st Century Society

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

One morning early last spring, my younger son and I were in an argument as I drove the boys to their respective schools. The subject was (in hindsight) entirely silly and unnecessary, but we both felt passionately about our positions and weren’t backing down. The argument continued right up until he got out of the car, which meant that (to the best of my recollection) for the only time during that entire school year, we didn’t say “I love you” to each other as he got out. I spent the remainder of the day paralyzed, unable to think about anything other than the possibility of a school shooting and of that angry drop-off being our last interaction.

Guns and gun culture in America have long been fraught and contested topics, subjects that quickly and potently divide us, issues that any public American Studies scholar addresses at his or her peril. I don’t expect to convert anyone to a radically different perspective than their starting point by writing about them here. But as stories of yet another school shooting unfold, I wanted to use my Considering History column to highlight a few histories that are, at the very least, relevant to engaging in these 21st century conversations.

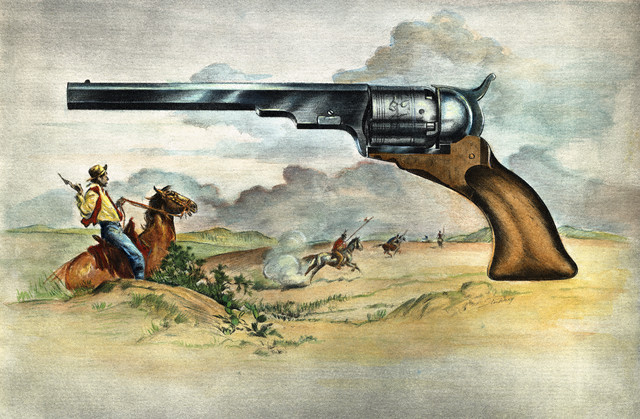

When it comes to scholarly works that trace the foundational, influential presence of gun culture and violence in America, the gold standard remains Richard Slotkin’s trilogy of books about the frontier: Regeneration through Violence: The Mythology of the American Frontier, 1600-1860 (1973); The Fatal Environment: The Myth of the Frontier in the Age of Industrialization (1985); and Gunfighter Nation: The Myth of the Frontier in Twentieth-Century America (1992). Slotkin’s use of “myth” in each subtitle doesn’t mean that he isn’t also tracing historical realities of guns and violence, but rather that his argument across all three projects is that those material realities became the basis of extended mythologies, cultural narratives that associated gun-toting historical figures (from Myles Standish and John Smith to Daniel Boone and Davy Crockett to Wyatt Earp and Annie Oakley) with foundational American values of freedom and independence (among others) — and that in the process turned stories of brutal violence into images of iconic heroism.

That’s all part of America’s story and identity, at every stage. But the Constitution represented something quite different from, and indeed in many ways contrasted to, such myths. The Constitution was an attempt to construct a legal and civic groundwork for the new and evolving nation, one in which its ideals were wedded not to icons but to ideas, not to stories but to structures. And as it did with so many aspects of early American society, the Constitution overtly addressed guns, as part of the Bill of Rights that George Mason and others fought to include in the document before the Constitution could be ratified by the states. The Second Amendment in that Bill of Rights reads in full: “A well-regulated Militia being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms shall not be infringed.”

Less than 30 words, in a complex sentence where the first dependent clause directly modifies the second independent one. Moreover, many of those words, including “well-regulated,” “Militia,” and “Arms,” have ambiguous meanings (individually, in relationship to each other, and in different historical contexts) that have become the source of extended debate. But one thing that the sentence’s grammar makes clear is that this is a collective right, one intrinsically tied — in a moment when the United States did not yet have a standing army, possessed no governmental military force that could defend the nation against foreign enemies — to the ability and indeed the necessity of Americans gathering in groups to help with communal and national “security.”

One important follow-up question, of course, was what that meant for individual Americans outside of such a collective role, and even (perhaps especially) in opposition to the government. The Constitution was silent on such questions, but just two years into his first term as president, George Washington had an occasion to address them. As I traced in this prior Considering History column, the March 1791 Whiskey Rebellion comprised a group of individual, armed Americans standing up against the government and its Constitutional duties. As their armed and violent rebellion grew, Washington organized a federalized militia (as the 1792 Militia Act authorized the federal government to do, spelling out in more detail the role of those militias mentioned in the Second Amendment) and marched west from the capital at Philadelphia, subduing the rebellion without further violence.

Washington’s choices and actions didn’t necessarily reflect the Constitution’s or the amendment’s original intentions, as no subsequent moment necessarily can (nor, indeed, can we know those intentions with any certainty). But they remind us that the well-regulated militias the Second Amendment seeks to guarantee played a central, federal role in this Early Republic period. These collected bodies of armed Americans were an integral part of the nation’s government and defense, one that continued to serve as America’s primary military force until at least the turn of the 19th century. Which is to say, the Constitution’s guarantee of the “right to bear arms” was, like every other element of the Constitution, directly tied to governmental and legal structures, linking individual rights to those collective, national necessities.

Many things have drastically changed in America since the 1780s, including of course the types of guns and weapons that are available to individual Americans (rather than simply for use by our armed forces), and the damage those weapons can do in a terrifyingly short time. Those contexts too must be part of our 21st century conversations, and of our legal and political definitions of “well regulated” and “Arms” at the very least.

But at the same time, some core Constitutional issues remain similar to what they’ve always been. One of them is the Constitution’s emphasis on collective identity and needs, on how “we the people” can “establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defense [and] promote the general Welfare” while still “securing the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity.” I’m not sure any communal experience reflects more clearly our frustrating current distance from those goals than horrific, ubiquitous school shootings. Doing everything we can to end that trend is as Constitutional as it is crucial.

Featured image: Daniel Boone escorting settlers through the Cumberland Gap. Painting by George Caleb Bingham, Washington University in St. Louis, Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum / Wikimedia Commons)

Sharing the Lamp of Experience

“I have but one lamp by which my feet

are guided; and that is the lamp of experience. I know of no way of judging of the future

but by the past.”

—Patrick Henry

These aren’t the most famous lines that Patrick Henry delivered in St. John’s Church on March 23, 1775. But with this speech — better known for his saying “give me liberty or give me death” — America’s founding firebrand invoked the power of history to light the fledgling nation’s way toward a better future.

Henry had captured an essential truth with ancient roots. “Study the past if you would divine the future,” Confucius had said centuries earlier. Today, a paraphrase of that maxim looms large in the heart of our nation’s capital, carved into the bases of two 65-ton statues titled Past and Future — the former, represented in the form of an elder man; the latter, as a youthful woman — seated outside the National Archives on Pennsylvania Avenue.

Understanding our past is no less critical now than it was in Henry’s time to building a better future for America. We would argue, in fact, it is all the more so, given the ever-increasing pace of change in social, political, and cultural affairs and the thick webs of connectivity linking communities and individuals today.

Yet that fundamental knowledge of our nation’s story, of our founding principles and our common national inheritance, is increasingly hard to come by.

This past February, results from a Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation survey revealed that only 4 in 10 Americans — and significantly fewer among those under age 45 — could pass a basic test of American history. Just 15 percent knew when the U.S. Constitution was written. Less than a third could correctly identify three of the original 13 states. Roughly 40 percent thought Benjamin Franklin invented the light bulb.

Sadly, these results were not outliers. Most Americans cannot name the three branches of government, according to findings from the Annenberg Public Policy Center. More than a third cannot name one right guaranteed under the First Amendment.

The news about younger Americans is even more alarming, although not exactly surprising. For years, our national zeal for more technical STEM-centered instruction, coupled with an increasing reliance on standardized testing, has driven social studies out of the classroom. Consequently, kids aren’t learning much of it. The last results of the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) revealed that 29 percent of American eighth-graders demonstrated “below basic” knowledge of U.S. history. Another 53 percent fell into the “basic” knowledge category, with just 18 percent registering “proficient” or better.

Almost three-quarters of those born before World War II considered it “absolutely important” to live in a democratically governed country. Just 30 percent of millennials felt that way.

And the story doesn’t get much better when our young people go on to college. In December 2016, George Washington University in Washington, D.C., announced that history majors are no longer required to take a single course on American history to graduate. This in a university that is named after our first president and located in our nation’s capital.

This begs the question: If the youngest generations of Americans grow up lacking a basic understanding of the past, ignorant and unaware of the essential beliefs which have guided our nation for nearly three centuries, what kind of nation will we be in 10, 20, or even 100 years from now? What kind of leaders will we produce? What kind of nation will we be leaving to future generations of Americans?

Former President Harry S. Truman wrote in his memoirs, “My debt to history is one which cannot be calculated. I know of no other motivation which so accounts for my awakening interest as a young lad in the principles of leadership and government.”

When the last results of the history NAEP were released, Michelle Herczog, then-president of the National Council for the Social Studies, put it another way: “Why is this important? The representative democracy established by our Founding Fathers calls for all members of society to be represented in legislatures, political offices, jury boxes, and voting booths. Unfortunately this vision has yet to be realized. …

“How do we, as a nation, maintain our status in the world if future generations of Americans do not understand our nation’s history, world geography, or civic principles and practices?” she asked.

How, indeed? The simple truth is we cannot.

It doesn’t have to be this way.

Older Americans, however, can help change this narrative — by meeting younger generations at the crossroads of America’s history, up close and in person.

- What better way to understand the foundations of our democracy than to visit Colonial Williamsburg, Independence Hall, the National Archives, Plymouth Rock, the Old North Church, or Ellis Island?

- What better way to understand our presidents than by visiting Mount Vernon, Monticello, Mount Rushmore, or the many presidential homes and libraries across the countryWhat better way to understand the sacrifices ordinary men and women have made over the years to defend our democracy than by visiting Gettysburg, Bunker Hill, Yorktown, Valley Forge, Appomattox, Fort Henry, the Alamo, Pearl Harbor, Little Big Horn Battlefield, the Vietnam Memorial, Arlington National Cemetery, the Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site, or the 9/11 Memorial and Museum?

- What better way to understand how inventors and great inventions have contributed to and changed our culture and way of life than to visit Kitty Hawk, Golden Spike, the Henry Ford Museum, the Kennedy Space Center, Hoover Dam, or the National Air and Space Museum?

- What better way to understand the impact of social movements on our nation and our people than to visit the National Museum of African American History, the National Museum of the American Indian, the National Historical Park in Seneca Falls, the GLBT History Museum in San Francisco, or the Rosa Parks Museum?

- And, what better way to understand the roots of our popular culture than by visiting the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, the Grand Ole Opry, the Autry Museum of the American West, the Cherokee Heritage Center, Fallingwater, or the various film, art, television, radio, and sports museums located throughout the country?

Sharing these experiences is what brings history to life. It helps us understand and appreciate who we are and where we are today. Most importantly, it inspires us to build on that history to create a better and brighter tomorrow for future generations.

In this age of short memories and even shorter attention spans, echo chambers, and tweeting in all caps, there remain thousands of opportunities for older and younger Americans to turn away from the noise and to reconnect with places where Americans fought for our freedom, found their inspirations, shaped our culture, and forged our most precious, guiding principles. By visiting the places where so much has been won, lost, and learned, America’s youth can begin to understand who we are as a people and what kind of future we want to build for ourselves.

Why ask older America to lead this charge? It’s not because everyone over the age of 50 is a scholar of U.S. history. We don’t all remember every word of the Gettysburg Address, and we can’t all recite details about the Louisiana Purchase or the French and Indian War. But many of us did absorb much of our knowledge of America’s story at a time when learning history was a more valued endeavor — in our schools, homes, and culture at large.

Throughout the ages, older people have served as our “keepers of the culture,” as the late Dr. Gene Cohen, a renowned psychiatrist and expert on creativity and aging, has pointed out. Transmitting a lifetime of knowledge and experience from an older person to a younger one can inspire dreams, create careers, spur innovations, and provide a fulfilling life. As our nation struggles to find a common purpose and a national identity, a journey to rediscover our American roots can be a means to our coming together to envision and build a better America for our children and grandchildren, and future generations.

Trekking to hallowed historic ground was once considered equal parts education, recreation, and civic duty. Visitation numbers don’t lie. In decades past, more school groups and families spent considerably more time and resources touring battlefields and presidents’ homes, historic halls of government, history museums, and ancient harbors and farms. It was part of our collective coming-of-age and, as a result, baked into our collective American identity. It was our shared national inheritance.

Consider, by contrast, the experiences of Generation Z, born roughly between 1995 and 2010. Studies show this young generation feels unmoored from our nation’s defining institutions, which they tend not to trust. And like the millennials who preceded them, only a fraction self-identify as “patriotic” (15 percent), in stark comparison to their elders. That’s according to a 2017 study by 747 Insights, a firm specializing in multigenerational research.

Now more than ever, young Americans need the chance to rediscover their country and find their place in its story. They deserve to hold history in their own hands, feel its pulse beneath their feet. At birthplaces, workplaces, and family homes of presidents and generals, artists, activists, and inventors, and the millions of Americans who were enslaved. At sites of military battles and of protests for political and social change.

At these crossroads of past and present, grandparents, great-uncles, aunts, and others can share with younger generations what they have lived and seen of America’s story, what they know and were taught of it themselves, and why it still matters. They can inspire a deeper understanding of — and interest in — our history. And in the process, they may renew and expand their own.

Older Americans share the lamp of experience because they have a burning desire to leave the world a better place than they found it. They also see the value in connecting the generations to build stronger intergenerational relationships. Taking younger family members (or volunteering to accompany other children on school or church trips, for example) to visit historical sites achieves both of these purposes, while helping to rekindle all Americans’ sense of national identity. It not only helps strengthen our connections with one another, it gives younger generations a greater appreciation for our national motto, E Pluribus Unum — out of many, one.

In his book How to Live Forever: The Enduring Power of Connecting the Generations, Marc Freedman points out that “Despite all the negative headlines … surveys reveal an extraordinary degree of mutual respect, most especially between boomers and millennials. And an overwhelming majority of older people say that the opportunity for future generations to prosper is important or very important to achieving America’s promise. We’re witnessing an incipient movement today of older people who are connecting with younger ones, standing up and showing up for the next generation, and resisting the mandate to go off in pursuit of their own second childhood.” So, at a time when there are more Americans over 50 than under 18 for the first time in history, the timing couldn’t be better.

We, too, believe strongly in connections across the generations, and in the power of historic places, because in our respective lines of work we witness their impacts every day. This is a potent formula for change that we feel an urgency to share. For if we do not reverse our collective, downward spiral into historical and cultural amnesia, our nation, and everything for which it has traditionally stood, will pay a very high price.

We believe, in fact, we are seeing the effects already. According to the last World Values Survey results published in the Journal of Democracy, almost three-quarters of those born before World War II considered it “absolutely important” to live in a democratically governed country. Just 30 percent of millennials — those born since 1980 — felt that way. If this is not a long-term threat, we’re not sure what is.

But there is hope. By visiting the past together, we come face to face with America as it was. In so doing we can truly understand how far we have come and imagine still how far we can go. We owe it to our younger generations, and ourselves, to take this journey together.

The possibilities stretch from sea to shining sea, from Ellis Island to Pearl Harbor. Events and movements have unfolded across every part of our landscape that continue to impact our world today. Take your grandchildren to the Susan B. Anthony House in Rochester, New York, and stand in the very room where the suffragette was arrested in 1872, just for casting a vote. Or head south with the family to the restored lunch counter at the original Woolworth’s building in Greensboro, North Carolina, where a 1960 sit-in catalyzed a protest movement across 20 states, involving 70,000 people. Try following the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail, stopping at memorials and museums along the way. As you cross any or all of the nine states and thousands of miles the trail covers, consider together the sheer magnitude of America’s mass relocation of Cherokee and other tribes during the 1830s, its injustice and the devastation it wrought, killing thousands in the process.

These are complex stories, yet they reverberate through time and impact our lives. By going to the source — to see, hear, and touch this history together, where it actually took place — we personalize and deepen our understanding.

Thomas Jefferson believed that an educated citizenry was essential to the preservation of American democracy. He argued that we can’t expect people to fight to preserve American democratic principles if they can’t define what they are. Without historical perspective and knowledge of how people lived, the sacrifices they made for our country, and how our institutions evolved, people have no basis for making rational decisions about the country.

We urge you to share your lamp of experience. It’s a first, important step. We owe it to them, to ourselves, and to future generations to take it — together.

Jo Ann C. Jenkins is CEO of AARP. Mitchell B. Reiss is president and CEO of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

Featured image: Shutterstock.

Considering History: Predatory Men, Vulnerable Women, and Foundational American Texts and Lives

This column by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

Relationships between men and women have dominated our national headlines and conversations for the last few weeks. We’re collectively debating questions of whether “boys will be boys” and what constitutes predatory behavior and sexual assault, and whether girls and women who testify to their experiences are vulnerable victims or manipulative “con” artists. In an extension of the #MeToo moment, we’re engaging with narratives of sex and agency, of ideals and realities of gender and relationships, and of whether and how women can escape or transcend all of these limiting images through their own voice.

While much about this moment feels strikingly new, these debates have been part of America since our founding era. Indeed, two of our first bestselling novels helped construct some of the first such images in popular culture, in two very different ways that parallel more and less sympathetic narratives of women, but ultimately portray them as powerless victims.

British-American writer Susanna (Haswell) Rowson published more than twenty books in the course of her prolific career, but it was Charlotte: A Tale of Truth (1791), that would become the bestselling early American novel. Despite its telling subtitle (partly an attempt to avoid the era’s critiques of fiction as immoral), Charlotte was not based on any one historical figure or story; instead, Rowson built on various contemporary images of sex and seduction to create her portrayal of a beautiful, naive 15-year old girl who was tragically used, abandoned, and destroyed by a predatory man and his privileged allies.

Charlotte’s world features a clear-cut vision of right and wrong, good and evil. From the first moment he sees the innocent Charlotte, the villainous English soldier Montraville sets out to seduce her, with the help of his equally predatory friend Belcour and Charlotte’s elitist teacher Mademoiselle La Rue. Their plot requires them to bring Charlotte to the United States, seemingly a more lawless space where Montraville can get Charlotte pregnant and then abandon her to her fate. That fate includes not just single motherhood and poverty but also defamation, shame, and eventually death, as Charlotte’s introduction to the world of romance and sex entirely destroys her. She is entirely passive but a thoroughgoing victim, not just of one predatory man but of an entire social order (Mademoiselle La Rue is particularly heartless in her consistent refusals to aid Charlotte). Rowson’s amplified the era’s narratives of young women as innocent, even angelic creatures located apart from adult society’s realities and vices, an impossible position for adult women to occupy comfortably.

Another early bestselling novel, Hannah Webster Foster’s anonymously published The Coquette; or, The History of Eliza Wharton (1797), offers a very distinct and much more critical (if certainly still nuanced) depiction of women and sex. Foster’s titular protagonist was based closely on the prominent and scandalous story of Elizabeth Whitman (1752-1788), a Connecticut socialite who was known for her flirtations with various social and literary figures and who, at the age of 36, died after giving birth in a Massachusetts tavern to a stillborn, illegitimate child. As stories of Whitman’s “disappointment” and death circulated throughout New England, minsters and other public figures used it as the occasion for moral lectures about sex and romance, and out of those narratives Foster created her “Novel, Founded on Fact.”

The Coquette creates its story out of letters between its main characters and others in their lives, and as such it does offer a multi-layered perspective and portrayal of its fictional version of Elizabeth Whitman. But while Foster’s Eliza Wharton is still in some ways the victim of a predatory seducer, the immoral Major Peter Sanford, she is also far more of a manipulative contributor to her own tragic fate: Wharton turns down the honest and dedicated affections of Reverend J. Boyer in favor of Sanford’s flirtations. When Sanford eventually leaves her to marry another woman, Wharton continues her affair with him nonetheless, and it is that adulterous relationship that produces the unmarried pregnancy that leads to Wharton’s shame and death. While Wharton is thus likewise destroyed by romance and sex, her “coquettish” personality and desires have made her a more active participant in that arc; in Foster’s narrative, women’s sexuality is at least in part a dangerous thing, one that links them to predatory men and scandalous ends. Since adult women could never quite remain the angelic figures illustrated by Rowson’s Charlotte, such narratives of their fallen and threatening nature became central parts of the period’s images as well.

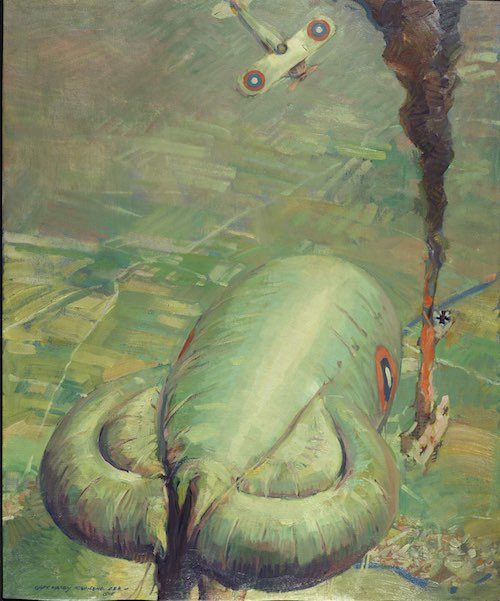

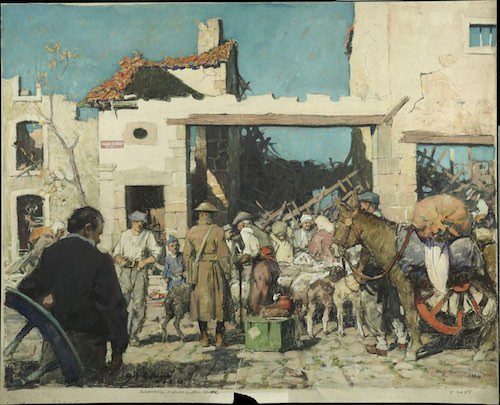

The Art of the Post: Forgotten Art Treasures from World War I

A hundred years ago, a select group of talented artists worked on the front lines of World War I, drawing and painting the human drama of The Great War. They captured the bravery and fear along with the boredom and exhaustion. But after the war ended, their eyewitness art was exhibited just once and then placed in storage at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington. Pictures of the human cost of the war — of flaming aerial combat around observation blimps, of poison gas attacks, of sacrifice and dedication — were quietly filed away in dark drawers where they’ve remained ever since, for the most part unseen and unappreciated by the public.

Now with the hundredth anniversary of America’s entry into World War I, these artworks have been rediscovered and placed on display in a wonderful and fitting exhibition by the Smithsonian, a joint project of the National Air and Space Museum and the National Museum of American History.

Our story begins in 1917, when some of America’s finest illustrators left their comfortable homes and families to work on the front lines of the “war to end all wars.” One of the artists, Harry Townsend, later wrote in his war diary, “I had gotten drunk, as it were, with the future pictorial possibilities in what I saw, and what my imagination saw, in the warfare that was so soon to come.”

Eight artists were chosen to accompany the American Expeditionary Force (AEF). The artists were commissioned as officers and given free rein by both the U.S. and French military authorities to depict everything from war preparations to the terrible toll of combat in the trenches. These “artist soldiers” included Saturday Evening Post illustrators Harry Townsend, Harvey Dunn, Wallace Morgan, William Aylward, and George Harding.

Townsend’s story was not atypical. He grew up in a small farming town in Illinois but was eager to see the larger world. Townsend’s war diary records his excitement about his upcoming adventure with the AEF: “I left New York in a blinding snow, into the submarine zone with its constant alarms, and through it. My trip through London … with an air raid thrown in …. and the nervous excitement of finding myself suddenly in the war zone, for, while one realized at all times the dangers on the sea, one really felt he had arrived when he found himself in the midst of the bursting of enemy bombs and the sight of enemy planes. …”

It didn’t take long for Townsend and his seven fellow artists to witness the effect of those bursting enemy bombs: “Everywhere among the blownup trenches and in the shellholes are pieces of what were once men. Here and there, a whole or a piece of bone; here and there a shoe with a foot still in it.”

Working at an astonishing pace, this team of artists produced approximately 700 works of art. The new exhibition has divided 65 of the best of these works into five categories:

- Engineers go to war

- Life at the front

- The technology of World War I

- The battlefield

- The human cost

Some of these pictures introduced Americans to the new sights and technology of modern warfare, but the exhibition’s curator, Peter Jakab, made clear in an interview that he thought the real contribution of this art was its human perspective. “Paintings by Harvey Dunn, such as The Sentry, Off Duty, and On the Wire exemplify the idea of the exhibition. They depict the soldiers’ war experience in a powerful, in-the-moment way, offering a realistic sense of the fatigue, loneliness, and stress of war. The AEF artists were the first true combat artists, attempting to capture the soldiers’ experiences in varied and intimate ways. The exhibition reminds us that all great, sweeping historical events are made up of the actions and experiences of individuals.”

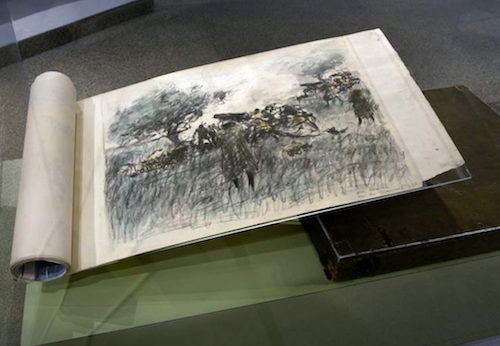

As the “first true combat artists” working in a brand-new kind of war, the resourceful eight were forced to improvise. Often they worked in rain and cold, which created challenges for their artistic ambitions. Yet they found practical solutions, so the quality and the quantity of their art remained quite high. For example, Harvey Dunn designed a protective metal sketch box that doubled as his drawing board and also contained a long roll of paper. This enabled him to continue to work seamlessly in the field.

Often the artists would sketch sights and experiences in the field and then return behind the lines to develop them into fully completed easel paintings. Many of the pictures created in the calm of a studio retained a power and vitality as a result of the artists’ preliminary sketches. Among my favorites was this powerful drawing in charcoal by Harry Townsend.

The talented William Aylward specialized in nautical illustrations for the Post but proved with his work for the AEF that he was an artist of great range and depth.

With World War I, the battle became more accessible to the public through mass communication, so images took on a different role. It is therefore not surprising that war art also changed. Before the artist soldiers of the AEF, official war art depicted war as heroic and romanticized battles. Even the great artist Goya, who privately lamented The Disasters of War in his unpublished series of etchings, continued to paint flattering portraits of pompous generals and aristocrats as brave commanders. But there is nothing false or regal or flattering about the pictures at the Smithsonian exhibition. They are as tough and practical as the Yanks who created them.

The exhibition at the Air and Space Museum has been well received by visitors. Says curator Jakab: “The idea that World War I, an event affecting millions, was fought by individuals, each with their own story, has relevance for today’s conflicts. Unless you have a family member or close friend in the service, it’s easy to think of one soldier as being pretty much like the next. Military families who come through the exhibition recognize and appreciate what this art reveals about the lives of individual soldiers in World War I, and the lesson it provides for our own time.”

The exhibition will be on display through November 11, 2018. For those unable to make the trip to Washington, many of the works, along with the background of the exhibition, can be found on the website for the National Air and Space Museum.

9 Places to Relive American History

These U.S. travel destinations tell the nation’s story through preservation, research, and reenactment. From prehistory to modern times, this is a bucket list for American history buffs.

Hovenweep

Built by ancestral Puebloans between A.D. 1200 and 1300, the towers of Hovenweep are a fascinating display of early masonry located at the border of Colorado and Utah, about 25 miles from the Four Corners. Hiking trails in the park offer views of the ruins as well as the canyons surrounding the Cajon Mesa. Hovenweep’s remoteness also yields brilliant stargazing opportunities from the onsite tent camp.

https://www.nps.gov/hove/index.htm

Minute Man Park

A wealth of American history lies in this National Historic Park that stretches from Concord to Lexington, Massachusetts. The five-mile Battle Road Trail leads visitors through various sites of the first battle of the American Revolution, and at the North Bridge you can relive “the shot heard ’round the world.” The Wayside, a preserved Colonial home, housed authors Louisa May Alcott, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Margaret Sidney throughout the 19th century, and Henry David Thoreau’s Walden Pond is located just south of the site.

https://www.nps.gov/mima/index.htm

Hamilton Grange

Alexander Hamilton’s Harlem home was moved twice before landing in its current spot in Saint Nicholas Park in Manhattan. The controversial Founding Father completed the home in 1802 on his 32-acre estate in upper Manhattan. Hamilton Grange tells the story of Hamilton’s self-made career and influential vision of industry. The recent restoration of the mansion was completed, inside and out, to replicate Alexander Hamilton’s original furnishings and landscaping.

https://www.nps.gov/hagr/index.htm

Homestead National Monument

Abraham Lincoln’s Homestead Act of 1862 provided 270 million acres of free land to Americans eager to start a life out West. The Homestead National Monument was established by Franklin D. Roosevelt in southeast Nebraska to commemorate the impact of Lincoln’s law on the economic and cultural development of the West. The site features 211 acres of prairie and woodlands preserved to represent the plains before settlement. You can tour an 1867 cabin and the Freeman School, a one-room schoolhouse that served students from 1872 to 1967.

https://www.nps.gov/home/index.htm

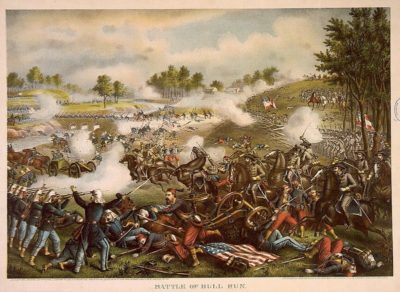

Manassas National Battlefield Park

The First Battle of Bull Run, the start of the Civil War, took place on the well-preserved grounds of Manassas National Battlefield Park. Civil War history buffs can experience reenactments and cannon-firing at this site just 25 miles from Washington D.C. Antietam, Harpers Ferry, and Fredericksburg battlefields are a short drive from Manassas as well.

https://www.nps.gov/mana/index.htm

Henry Ford Museum

The largest museum complex in the country houses a plethora of artifacts from American history, particularly from the Industrial Revolution. Thomas Edison’s laboratory, JFK’s presidential limousine, and the bus on which Rosa Parks took a stand all reside at the museum’s campus in Dearborn, Michigan. Most notable is the museum’s collection of cars that spans the history of automobiles in the United States.

New Orleans Jazz National Historical Park

Located in Louis Armstrong Park just blocks away from the French Quarter, the New Orleans Jazz National Historical Park is a new kind of national park that offers programs and tours to educate visitors on the birthplace of jazz. Rangers guide groups through jazz walks of the city as well as interactive demonstrations. The park also offers free concerts at a venue in the French Quarter.

https://www.nps.gov/jazz/index.htm

Birmingham Civil Rights Institute

The BCRI strives to act as a “living memorial” to the civil rights story of Birmingham, Alabama. Dramatic and interactive exhibits depict the civil rights movement in Birmingham as a necessity for understanding present and future human rights, as well as the past. The museum is situated in downtown Birmingham, close to other key sites from the Birmingham movement.

http://www.bcri.org/index.html

USS Midway

From 1945 to 1992 the USS Midway was an active aircraft carrier, but now the vessel rests in San Diego as a museum ship. Guided tours, flight simulators, and 29 restored aircraft from World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and Operation Desert Storm are aboard the massive carrier.

House Detective: Finding History in Your Home

Like the 250-year-old house from Ipswich in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, your home has a story to tell and a place in history. Whether you own your house, rent it, or live in an apartment, you and your family can become house detectives and discover the history of your home.

1. Start at home. The best source about your home is the building itself, and everyone in the family can join in this part of the investigation. Look at the separate parts of the building—roof, walls, chimneys, doors, windows, and foundation. Note what materials they are made of and how the different parts are joined to one another. Try to distinguish original materials from later additions.

Look at the style of the house, too, inside and out (and use the books listed on the back panel of this brochure to help identify building styles and materials). The style of a building is a clue to its age—but not proof. In some parts of the country, a building style stays popular longer than in others. Keep careful notes and take pictures. The clues you record will be useful later on in your investigation.

2. Go to the courthouse, or wherever deed records are kept in your community. Using deed records, you can create a chronological list of all of the owners of a piece of property. The list you compile will be the backbone of your home’s history.

Ask for the index to deeds by buyer. Start with the deed to the present owner. Note the seller’s name and the legal description of the property. Then use the index to find the seller’s deed to the same piece of property and note whom the seller bought it from. Work your way back through the deeds to the original owner, make a copy of each deed, and keep track of the page and volume numbers. A sharp increase in the value of the property could mean a building was added to it.

3. Look at other public records, especially if you find gaps in the deed records. Sometimes property passes from one owner to another through a mortgage or a will, and these documents will probably be wherever you found the deeds (or at least nearby).

Mortgage records often contain detailed descriptions of buildings. Wills and other probate records may list one or more of the previous owners, and you can examine the records filed under their names to see if there are any mentions of the property. Local tax records may reveal the dates of additions and improvements to property by a change in its valuation, and maps of property made by surveyors can show a tool shed or a well that no longer exists. Be sure to make photocopies of all the records that you think will be helpful.

Photo courtesy of the National Museum of American History.

City directories often list people’s occupations as well as addresses and can help to establish the dates that a person lived at a particular address. A librarian can also direct you to federal and state census records. They can contain vast amounts of information about households.

A good library or Internet project for children is to create a timeline of American history starting with the approximate construction date of your building. When the kids have completed a simple timeline for the nation, the family can work together to combine it with the timeline for your home and look for connections. You might find a

link between a big event in American history and a small event in your home’s history.

5. Read a map. Your librarian can guide you to city and county maps that may show your building with the owner’s or resident’s name written beside it. Such maps often show the location of old roads and other landmarks that may have disappeared. Insurance maps, especially those produced by the Sanborn Map Co., contain a wealth of information about individual structures, including the materials from which they were built.

6. Look at a picture. Your local library or historical society may have old photographs of your building, or there may be some in your neighbors’ attics. Postcards can be helpful, too. Many towns are represented in nineteenth-century lithographs called “bird’s-eye views,” which sometimes provide an accurate picture of every residence in town. Don’t forget to take a few photographs of your home for the project, or better yet, have children in the family take the photographs or draw pictures of your building.

7. Talk to people. Try to track down former residents or their children. They may be able to help you date changes or tell you stories about their lives in your home. Neighbors can be helpful, too, if they have lived in the neighborhood a long time. The whole family can put together a list of questions to ask the neighbors about your home and neighborhood. While you are talking to them, ask if they have any family pictures that might show your building in the background.

8. Put it all together. When you have finished your research, you will have a stack of written notes, photocopies of documents and maps, and photographs. These are like the pieces of a puzzle. Use them to create a timeline of your home’s past and to write a narrative history. Enlist everyone in the family to help create a scrapbook that weaves together the narrative history, photocopies, drawings, and photographs, and then make enough copies to give your family and friends. Be sure to place a copy in your local historical society or library, so that your home will have a place in history.

9. Is the building you’re living in brand new? Then start your own history of your home. Using some of the steps outlined above, find out what was there before your building was built and why the neighborhood changed. Then take photos of your home and write about your experiences living in it. You will be making history for your family and community.

Further reading. These books to may help in your research:

Barbara J. Howe. Houses and Homes: Exploring Their History.

Nashville, Tennessee: American Association

for State and Local History, 1987.Howard Hugh. How Old Is This House?

New York: Noonday Press, 1989.Sally Light. House Histories: A Guide

to Tracing the Genealogy of Your Home.

Spencertown, New York: Golden Hill Press, 1997.Virginia and Lee McAlester. A Field Guide to American Houses.

New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997.

Visit the “Within These Walls…” website at

http://americanhistory.si.edu/house.

When I Was Young And Charming

The 1929 movie “Cocoanuts” made Groucho Marx a star at age 39. That year he wrote about the changes he’d seen in his two decades as an entertainer. You’d need at least an associate degree in American History to understand most of his references to obscure events and vaudevillians. Still, it’s interesting to see what nostalgia looked like in 1929.

Vaudeville was at the height of its popularity, and three performances a day, with four on Saturday and five on Sunday, was considered a vacation. A week which only called for one split engagement was a rest cure.

The standard vaudeville wage was forty dollars for a single and sixty dollars for a double; quartets were paid $150 and headliners $200.

Theater curtains were rolled on a log, and to be hit by one was sure death. Stage hands changed the sets in full lights and their shirt sleeves, and the proprietor’s daughter always played the piano. That’s how he came to be the proprietor.

The Three Nightingales became the Four Marx Brothers when Brother Arthur joined the act. When he spoke his first lines we realized he was born to be a pantomimist. We laughed indulgently when he said he’d like to take lessons on a harp and our act was called “Fun In Hi Skool.” This spelling was considered to be very comical in those days and, in fact, was the biggest laugh in the act. As I recall it now, it was the only laugh

Art Fischer,a monologist, disturbed our poker game in Champaign, Illinois, by calling Arthur “Harpo”; Leo “Chico”; Herbert “Zeppo”; and me “Groucho.” He was the only kibitzer on record who ever said anything of value.

Our booking agent was one Minnie Palmer and so was our mother.

Railroad fare was two cents a mile, and hotels had a standard rate of six dollars a week, including a midnight supper after the show.

The musical saw had not made its appearance on the vaudeville stage, and every burlesque show had an Irish and a Jew comedian, as well as a rich widow. It was considered quite the thing to have the saxophone player stretch out across the piano, and the violinist was a bust unless he could fiddle behind his back. All good drummers threw their sticks in the air, and the member of the orchestra who played the loudest was made the leader.

Harvard still won football championships… and men who played golf were considered effeminate. Every well-dressed man wore an elk’s tooth for a watch charm, and a fellow who could blow smoke rings was a social success.

It was a swell house that had more than one bathroom There were very few two-car families, but there was always meat on the table. No hot dog was complete without sauerkraut. Liver was given away with each purchase of meat

Chorus girls were picked for weight, not speed, and shop girls work silk stockings only on Sunday.

“Skidoo” was considered a pretty smart crack. Girls blushed when a wise-cracker would say, “Oh, you chicken!”… and only in a terrific windstorm were a girl’s knees visible.

What the country needed was a good three-cent cigar Beer was a nickel a glass… and dinners with candles were unknown except in homes of plumbers.

Half the population had stiff necks from looking at Halley’s Comet, and you could park as long as you liked in Times Square.

Actors spent their spare time in pool rooms, and if anybody had told me that a magazine would pay me to write articles I would have sneered derisively — If I had known what that meant.

Smithsonian: Within These Walls

Through its exhibition, Within These Walls…, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History showcases 200 years of American history as seen from the doorstep of one house that stood from Colonial days through the mid-1960s in Ipswich, Massachusetts. Opened May 16, 2009, the 4,200-square-foot exhibition highlights five ordinary families whose lives within the walls of the house became part of the great changes and events of the nation’s past.

“Ordinary people, living their everyday lives can create extraordinary history,” said Spencer R. Crew, director of the National Museum of American History. “This exhibition will inspire our visitors to look at history in a new way, a history that begins at home,” he added.

The exhibition is sponsored by the National Association of Realtors®. “This truly is a historic event for NAR to be able to bring “Within These Walls…” to millions of visitors, said NAR President Richard A. Mendenhall.

The exhibition’s curatorial team researched nearly 100 occupants who once lived in the house. Their stories show some of the ways Americans have made history in their kitchens and parlors. Inside this house, American Colonists created a new genteel lifestyle, patriots set out to fight the Revolution, and an African-American struggled for freedom. Neighbors came together to end slavery, immigrants made a new home and earned a livelihood, and a woman and her grandson served on the home front during World War II.

For more details, visit the exhibition Web site. Curious about your own home?

Photos courtesy of the National Museum of American History.