Vintage Ad: Bite-Sized Bread Model

In 1942, Quality Bakers of America commissioned artist Ellen Segner to develop an identity for their new Sunbeam Bread. She was a good choice — a well-known illustrator who had painted all the characters in the iconic 1950s Dick and Jane books.

Marilyn Kille remembers modeling for the Miss Sunbeam character when she was 5. She recalls being intimidated by the photographer who kept disappearing beneath the black hood of his studio camera. She was placed on a tall stool and directed to take a slice of bread from a tray on her left. She was to then take one bite from a specified corner and, the photograph taken, let it fall into a trash bin on her right.

She followed the instruction but grew agitated the longer the session continued. Tears welled up in her eyes and soon ran down her face. Everything stopped. When the staff asked her what was wrong, she wouldn’t answer. The photographer decided he had enough photos and called an end to the session.

If you were a child in those years, you might remember being admonished never to waste food; there were “children starving in China,” after all. Taking those warnings to heart, Kille was crying because of the growing pile of discarded bread. She would surely be punished for wasting food and depriving all those hungry Chinese children.

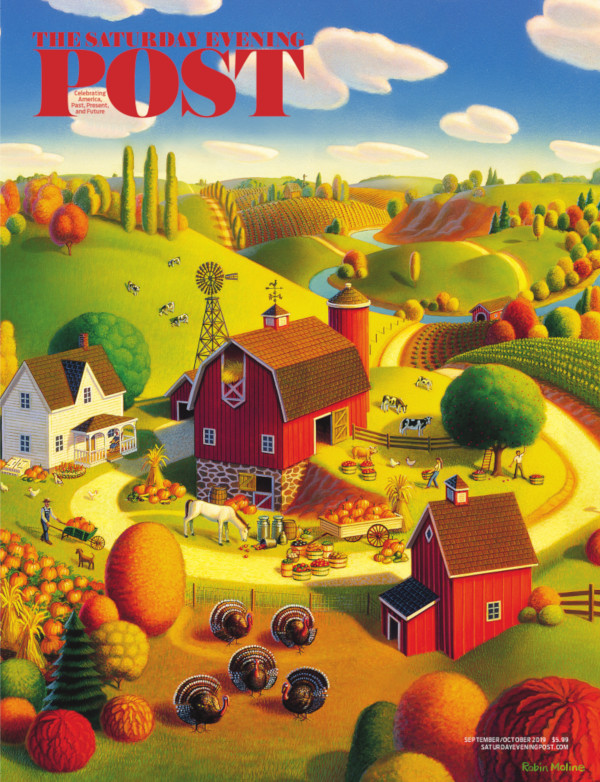

This article is featured in the September/October 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Post Artists: Stevan Dohanos

See all Post Artists Videos.

Featured image: Stevan Dohanos / SEPS

The Art of the Post: The Ornery Illustrator

Read all of art critic David Apatoff’s columns here.

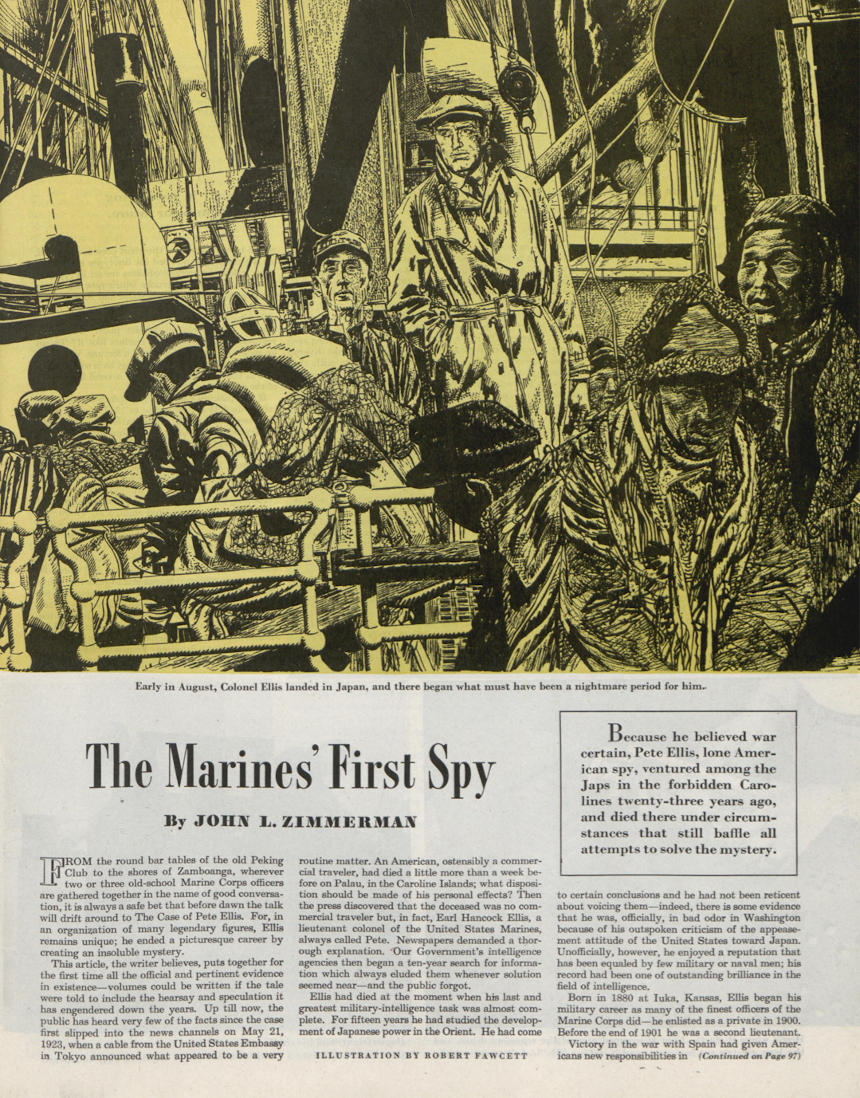

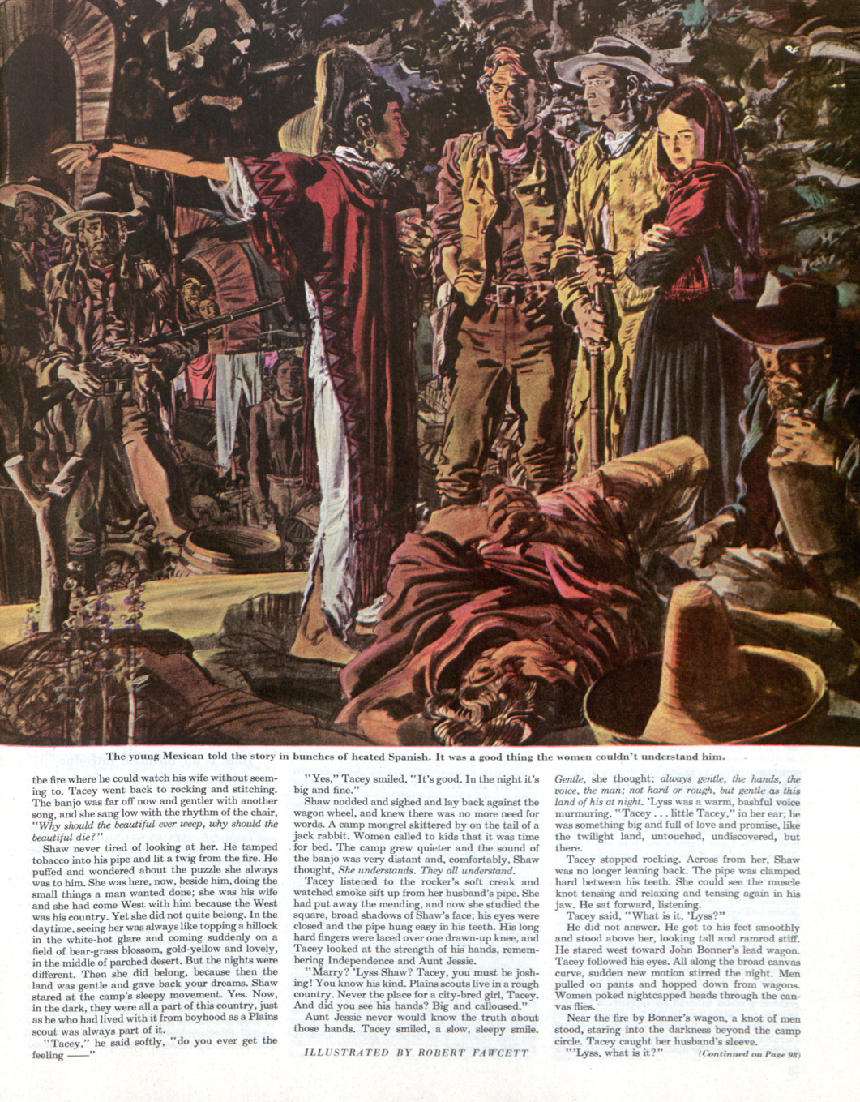

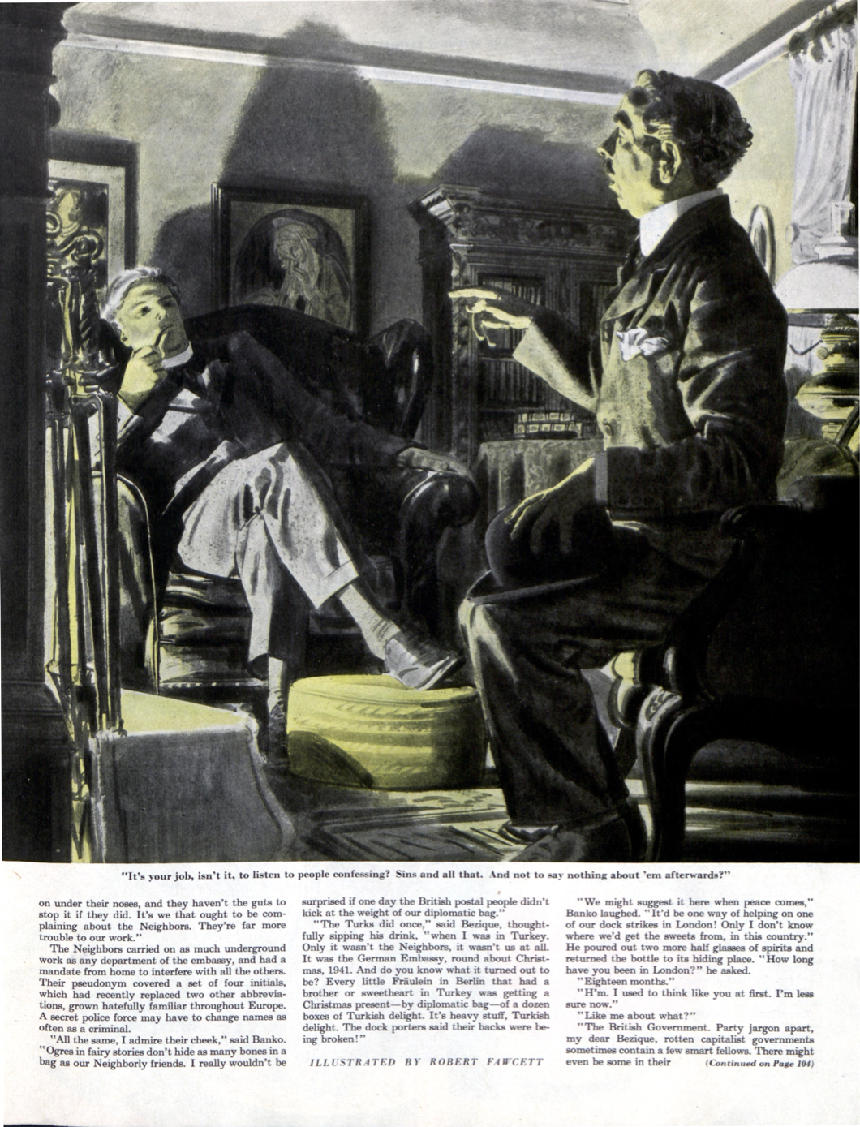

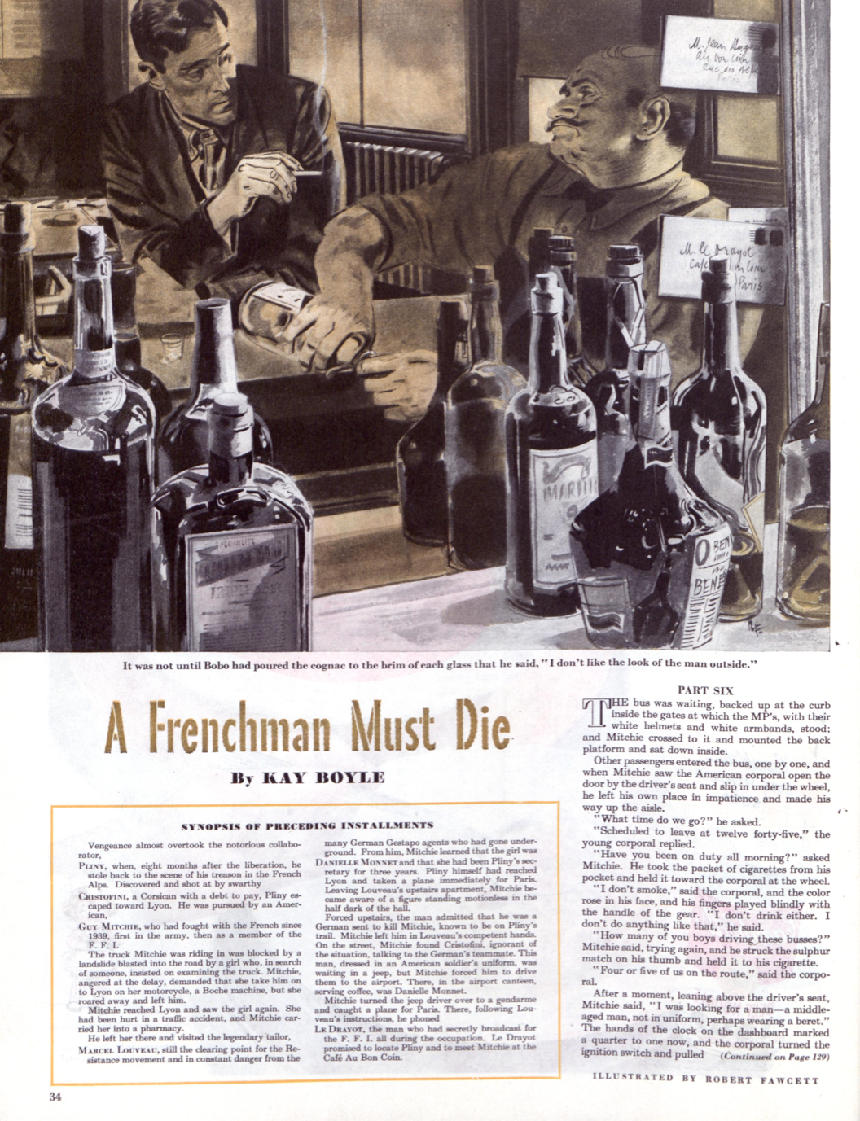

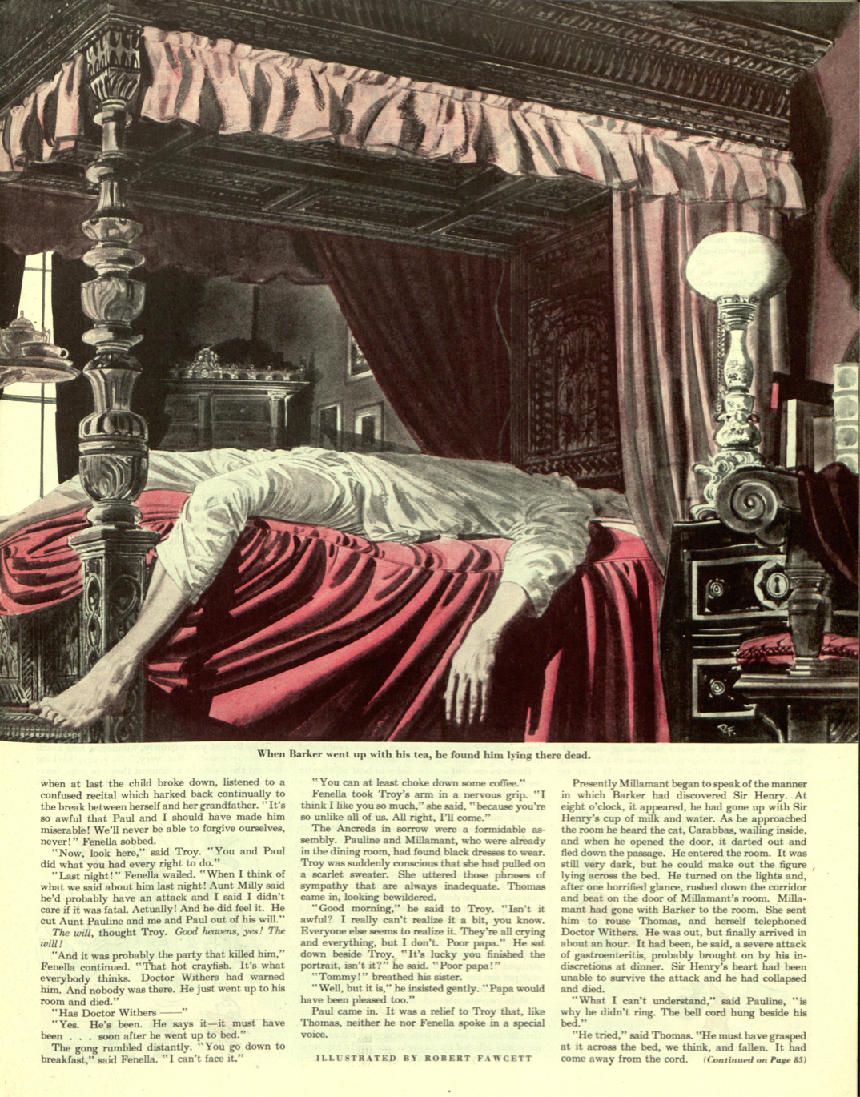

Robert Fawcett illustrated for The Saturday Evening Post in the 1940s and ’50s. He was known as one of the best draftsmen in American illustration…also one of the most prickly.

Fawcett had no patience for diplomacy. Brilliant, opinionated, and candid, he had strong views about everything from art to politics, and was fearless about expressing them, whether people wanted to hear them or not. Friends recalled that he could be quite intimidating.

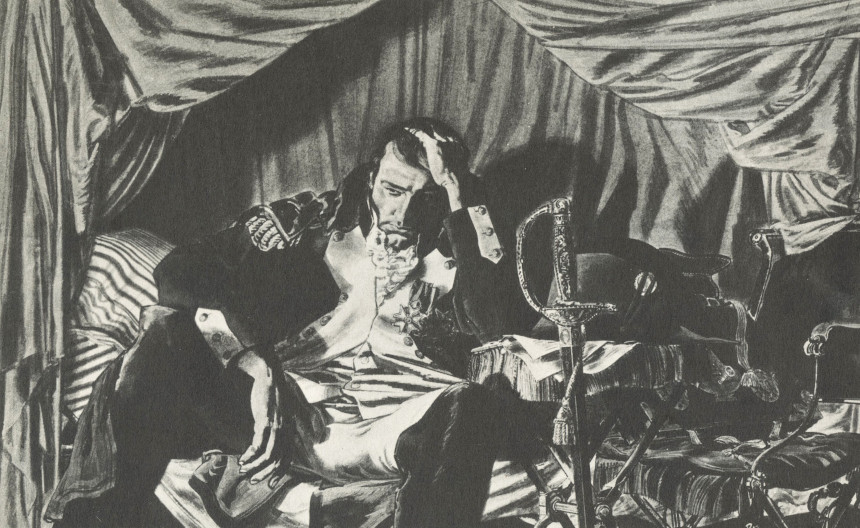

On one occasion, a client instructed Fawcett to revise the face on an illustration of Napoleon. Fawcett refused. He felt the client’s bad idea would diminish his picture, so he kept the picture for himself.

On another occasion, Fawcett turned down a plum assignment to illustrate the hit musical Oklahoma! Fawcett made preliminary sketches, but an art director suggested that Fawcett could improve the image by making the illustration more “theatrical,” putting bright colored shirts on the cowboys and making them more flamboyant. Fawcett replied that he was not interested in working in that style, and suggested that another illustrator would be better suited for the job. He returned the project to the client.

Fawcett would scold politicians, advertisers, publishers, and artists for their low standards or ignorant views. A less talented artist never could have gotten away with such behavior, but everyone had such respect for Fawcett that he never lacked for friends or assignments.

Fawcett was born in 1903. As a boy, he loved to draw and trained in lithography shops, advertising agencies, and commercial art studios — wherever he could find work. His dream was to attend London’s Slade School of Art, which was famous for training several generations of the best draftsmen in England. The school prided itself on stripping away all gimmicks and artifice and focusing on pure drawing skills — exactly what Fawcett wanted.

By the time he was 19, Fawcett had saved enough to pay for two years at Slade. He studied there from 1922 to 1924 and got a tough, old fashioned art education. Fawcett recalled that under the watchful eye of stern teachers, “I did nothing but draw from the model eight hours a day for two years.”

Fawcett returned to the U.S. and began his career as an illustrator. In an era when the popular illustration style was to paint in bright colors, Fawcett — who was color blind — developed his own distinctive methods. He would draw a picture in black ink, and then paint over it with washes of color, which he often had to select by reading the label on the paint tube.

He soon became famous for his eccentric working habits.

Art Director Howard Munce described Fawcett’s technique for creating his own drawing tools: “Bob had a habit of poking around the studios of his friends and finding beat-up brushes that had known better days. The owner was always amused and pleased to give them to him when he showed an interest. Back in his own studio, he’d give the tired discards a shave and a haircut with a sharp blade and refashion them to suit his needs. Mostly he made wedged tips of various angles to serve special functions in his illustrations. In his hand, an old brush would begin a new life. He might use it to stroke in lines, to indicate a complicated bit of rococo molding, or to scumble in a particular texture. But however he used it, it would always leave his unmistakable imprint.”

Similarly, when magic markers were invented Fawcett was among the first professional artists to use them. Most illustrators stayed far away from the strange new medium because they were unpredictable and frustrating. Fawcett seized upon them and converted them into his own customized tools. He would whittle and reshape the felt nibs, or deliberately let them dry out to create a rougher line. He showed how to use the new tools to maximum advantage. The manufacturer of the new pens, Flo-Master, was so delighted when it saw how Fawcett was able to make use of their product that they sent him a lifetime supply. Knowing Fawcett’s reputation for high standards, they made an ad bragging that Fawcett used their markers.

In 1945, Fawcett’s career took a big leap forward when he received his first assignment for the Post, a serial entitled, “Cadmus Henry and the Hand of God.” This initial project was so well received that Fawcett was asked to be a regular contributor and soon graduated to the top of the Post’s pay scale.

A few weeks after his illustrations appeared in the Post, Fawcett was invited to lecture to students at the Society of Illustrators in New York. Fawcett was skeptical. “I’m willing, he responded, “but who wants to hear me?” When word spread that Fawcett was going to speak, the leading illustrators of the day flocked to the hall and crowded out the students. The event became standing room only, with established artists overflowing into the corridor and out the door, straining to hear what Fawcett had to say. He had arrived.

Fawcett’s success didn’t cause him to soften his views one bit. In interviews and in published essays he openly criticized the bad taste of the advertisers who paid for his work and the magazines who published it. In The Annual of American Illustration from the Society of Illustrators (1961), he wrote, “[T]he advertising and publishing fraternities pander to the lowest common denominator or make obeisance to expediency for temporary profit. [These people] will stand revealed in their mediocrity if it continues.” Fawcett said that illustrators needed to play a role in educating the artistic taste of the public, “showing [advertisers and publishers] who now stand as arbiters of the public taste just what that taste can be developed to accept.”

In an interview in American Artist magazine Fawcett acknowledged that illustrators faced powerful pressures to lower their standards. This was primarily because of “the intrusion of the man who pays the bills — the client. His position gives him the right to prefer and to buy mediocre illustration…and he exercises this right with almost unfailing regularity….The artist must know and accept this situation…where a large income is the prime motive.”

But he exhorted his fellow illustrators not to let income be their prime motive: “It should be the aim of every illustrator to withstand the tendency of publications to force his work into a mold, to make him conform to an accepted pattern. This is a difficult thing to do — the financial rewards of conforming are great…. We must be ready to refuse work unless it allows us to conform in some degree to standards that we ourselves set, and the result should add life and character to the printed page….”

When it came to politics, Fawcett was a flaming liberal. He would sometimes start his day writing angry letters to politicians or newspapers, fuming about some social injustice or other. He made his opinions known about schools, zoning, and community affairs. He rejected both the Republican and the Democratic parties because “prejudice, bigotry and fear in the U.S. are not the characteristics of only one party.” He was a lively conversationalist and loved to debate current events, but the wealthiest man in town stopped inviting him over for dinner when Fawcett predicted that his host’s mansion was going to be converted into a retirement home for workers.

Fawcett was not an easy man to live with, but for those who were strong enough to cope he proved a scintillating companion. He lacked much formal education, but his house was a center of cultural activity. He had a strong interest in music and became friends with world famous musicians including Arturo Toscanini and Jascha Heifetz, who visited him at his home. He related music to the abstract designs that were the foundation of his “realistic” pictures. He studied Beethoven’s notebooks and believed that Beethoven’s thematic notations were very similar to an artist’s conceptual sketches: they are both “notations of plastic linear ideas.” Fawcett said that abstract drawing “is probably as close to music as drawing can come.” He claimed that the greatest influence on his illustrations came not from the visual arts but from opera.

Fawcett also kept company with a wide variety of modern artists, such as the English sculptor Jacob Epstein. Original drawings by the abstract sculptor Henry Moore and another friend, the modernist painter Graham Sutherland, hung on his walls. He was also highly regarded by his fellow illustrators even when they didn’t socialize with him. When Fawcett wrote a book about his theories of drawing, Norman Rockwell called it a “great contribution to art as well as illustration.”

Fawcett never became as famous as Rockwell or other well-known illustrators of his day, but that was Fawcett’s peculiar trade off. He believed that an illustrator who wanted to protect his or her abilities had to be prepared to give up some profitable assignments if necessary, and to sacrifice part of his or her popular audience. And if you had to insult a few clients along the way? Well, apparently that was just a bonus.

Featured image: Robert Fawcett / © SEPS

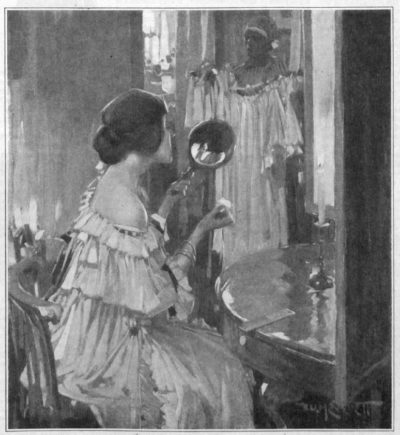

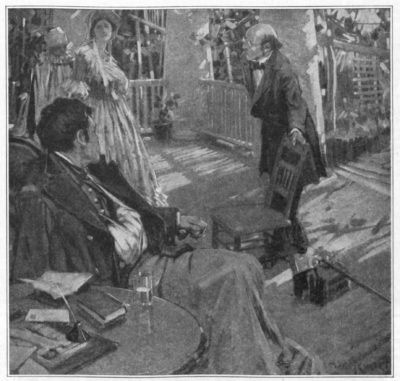

The Art of the Post: The Mystery of Walter Hunt Everett

Read all of art critic David Apatoff’s columns here.

One of the most promising young illustrators ever to work for The Saturday Evening Post was Walter Hunt Everett.

At a very young age, Everett was recognized as immensely gifted, a potential successor to Howard Pyle, the father of American illustration. Some thought his talent rivaled the young Norman Rockwell. But halfway through his career, at the height of his powers, Everett mysteriously dropped from sight. He quietly passed away in 1946, largely forgotten.

In 2014, the Society of Illustrators resurrected Everett’s reputation and elected him to their Hall of Fame based on the first half of a promising career. Illustration expert Kev Ferrara, writing for the Society, enthused: “based on the evidence he left behind, the man was a genius.” Ferrara noted that Everett was “deservedly revered during the Golden age of American illustration,” and concluded that his few remaining paintings showed Everett was “among the most daring and inventive of the great illustrators.”

So what happened?

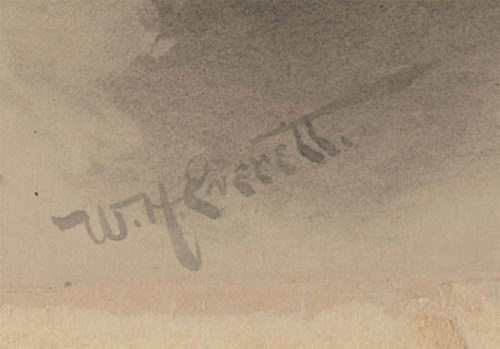

Everett’s childhood revolved around his drawing and painting. He rode a bicycle 30 miles to take art lessons from Pyle, who immediately recognized Everett’s potential. When he graduated from Pyle’s school, Everett drew this elaborate sign as his notice to the world that the young illustrator was open for business:

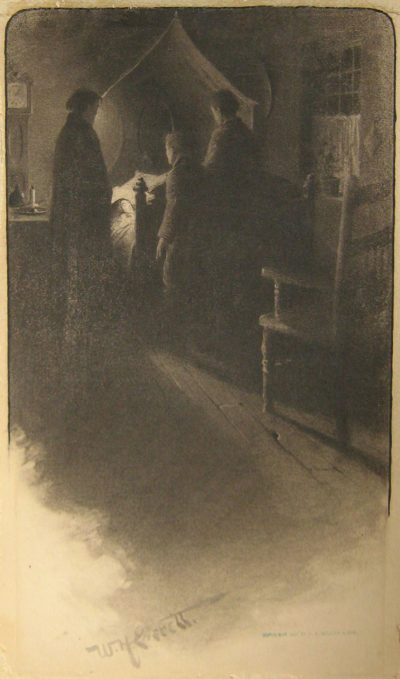

Everett quickly found work for some of the most prestigious illustration markets in the country. For example, at age 20 he drew this beautifully composed picture for Colliers:

Note how Everett put his bold and prideful signature right up front:

By age 30, Everett was a regular artist for The Saturday Evening Post. He painted his first cover in 1910 and served as a regular contributor from 1910 to 1917. Unlike famous Post illustrators such as Rockwell and J.C. Leyendecker, Everett did not paint in a consistent, realistic style. He experimented with vignettes and later with flat patterns and compositions created by light.

©SEPS

Everett was such a perfectionist that he sometimes ignored his deadlines in order to get things right. He spent countless hours mastering his craft, working with paintings, and trimming and reshaping his beloved brushes. He even designed his own easel (which he imported from France). In 1917, he stopped working for the Post’s deadlines to work more intensely on the art that interested him. Around the same time his neglected wife and son finally lost patience with his art obsessions and left him.

Reaching maturity, Everett turned out paintings that were a cross between illustration and fine art:

This painting is a masterpiece of color and light, but Everett worked on it so long that his client didn’t have time to print it in color, so they had to settle for black and white.

Then, in the 1930s at the peak of his career, in what must have been by an act of howling madness, Everett “gathered the bulk of his life’s work,” burned it to ash and disappeared from illustration forever. His family reported that he moved to the small, quiet town of Parker Ford, Pennsylvania where he seems to have spent his remaining years chipping away at stones to make arrowheads. He purportedly made thousands of them.

His family recalled that by this time “he could not care for himself.” There was speculation that he suffered from depression or some other mental disability. His ex-wife returned to his side and nursed him until he finally passed away from emphysema.

Instead of a rich legacy of hundreds of paintings left behind by other Post illustrators such as Rockwell and Leyendecker, Everett left behind a cardboard box full of arrowheads.

Featured image: Cover from October 15, 1904 (©SEPS)

The Art of the Post: The Artist Who Kissed a Painting by Botticelli in the Dark

Read all of art critic David Apatoff’s columns here.

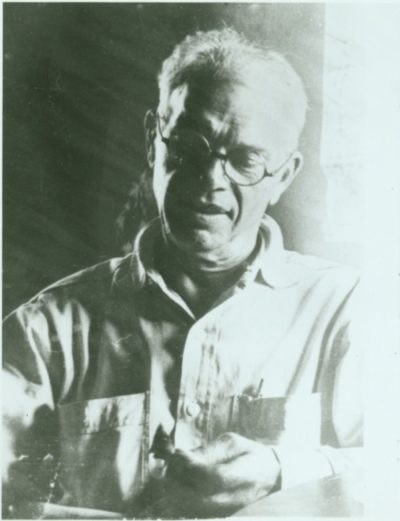

Many of the great artists who worked for The Saturday Evening Post led colorful, interesting lives. One such artist was Stanley Meltzoff, a classically trained artist who worked for the Post between 1956 and 1960.

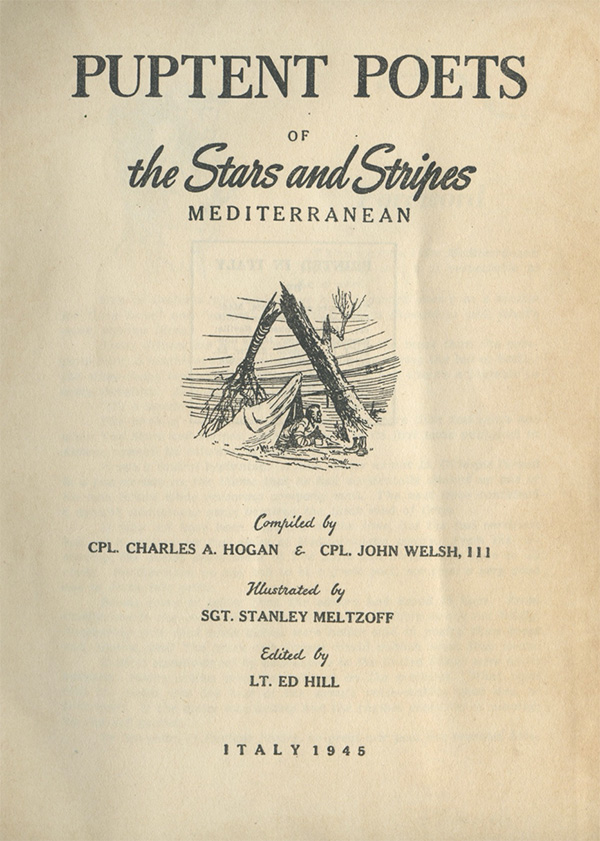

Before World War II, Meltzoff was an art student who traveled in Italy to study the Renaissance painters. When war broke out, it was only natural that the army put Meltzoff’s knowledge of Italy to use in an intelligence unit assisting with the invasion of Italy. Meltzoff was sent to the landing at Anzio, and when the front lines broke open he entered Rome with the first G.I.s. His role included drawing battle maps and Italian locations and translating key Italian phrases for the G.I.s in the army newspaper, Stars and Stripes. Even in the midst of war, Meltzoff was eager to find a way to draw, so he volunteered to illustrate poems that soldiers sent in to Stars and Stripes. These were published in a book entitled Puptent Poets.

Meltzoff spent three years in Italy as the war raged. The greatest art of the Italian Renaissance was in danger of being destroyed in the fighting, so paintings were evacuated from museums and hidden in the countryside. The entire contents of the famed Ufizzi Gallery in Florence were hastily moved to a remote country villa to protect it from bombing.

As Meltzoff recounted in an interview in the forthcoming book, Stanley Meltzoff: Picture Maker, he was driving a jeep along the Arno River in an area being shelled by German and Canadian artillery when he came across an abandoned villa. Later he wrote about what he discovered there:

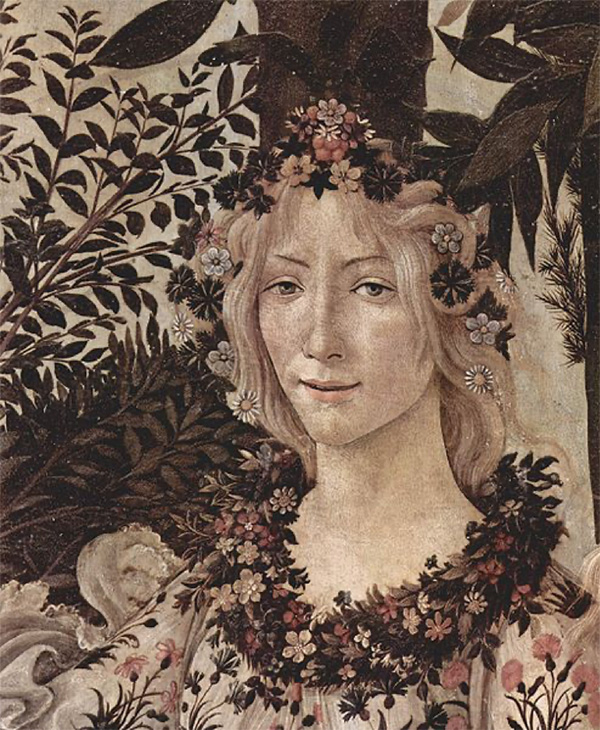

…I saw close up the masterworks I had only known from books. The whole inventory of paintings in the Ufizzi was leaning against the walls of the Sitwell’s villa south of the Arno where they had been tucked away in the countryside in case there might be a battle for Florence… The villa was empty, the room I entered was empty. A rooster was perched on a stack of panels in front of which was the Primavera of Botticelli.

The legendary painting Primavera, about the birth of spring, was created around 1480. It has been described by art historians as “one of the most written about… paintings in the world.” It shows the cold gray wind of March coming in from the right, kidnapping and possessing the beautiful nymph Chloris. The wind marries Chloris and she transforms into the deity Flora, the goddess of spring, the eternal bearer of life. We see Flora here scattering the rose petals of spring on the ground.

Meltzoff stood transfixed in the dim light, staring at the painting.

Flora, life size, was scattering her flowers. As in my dreams I stepped up and kissed my ideal of beauty full on the lips…

Meltzoff survived the war. Like the goddess of spring he experienced a rebirth, a career he called his “happy period” painting beautiful oil painting illustrations for The Saturday Evening Post, Life, and other top magazines.

He went on to a distinguished career as a gallery painter, enjoying a long, lucrative career as a painter and an author before he finally passed away in 2006.

But it’s clear that his youthful kiss in the dark with his ideal of beauty remained fixed in his mind. Just as Botticelli painted the Birth of Spring later in life, Meltzoff painted his own Birth of Autumn.

Like many of the illustrators who once worked for the Post, Meltzoff’s work has been rediscovered by a new generation of art lovers. A new book about his art and career, Stanley Meltzoff: Picture Maker, is available from Illustrated Press.

Featured image: Primavera by Sandro Botticelli (Uffizi Museum, Wikimedia Commons)

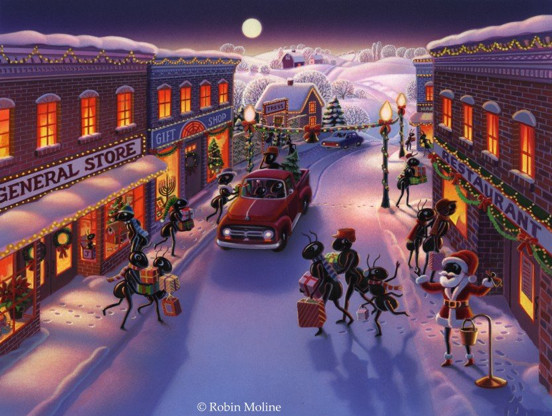

An Interview with Our September/October 2019 Cover Artist Robin Moline

Saturday Evening Post: Can you tell us more about what inspired you to paint the image that appears on the September/October 2019 cover of The Saturday Evening Post?

Moline: This painting was originally commissioned for tapestry art, but I decided to go ahead and create an image that I could also sell for prints and as a stock image. So I basically went to town, put myself into the scene and tried to imagine what the look and the feel of that kind of day would be. The painting had to tell the story and transport the viewer there too.

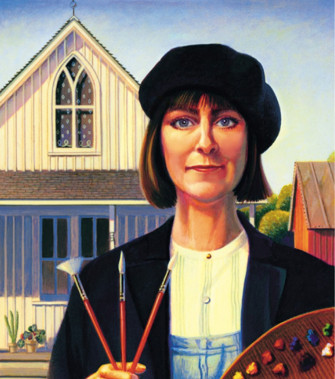

Post: You describe your style as “a surreal look with an often folksy twist.” Many of your illustrations pay homage to or are reminiscent of Grant Wood. I would describe them as “Grant Wood on acid.” What attracts you to that style of illustration?

Moline: I have heard my artwork described like that before. I’d like to think that I take Regionalism imagery and that folksy style and amplify the colors to make my artwork have a more contemporary feel. What attracted to me to this style is hard to say. I suppose first I always enjoyed painting landscapes from an early age and often they were of rural subject matter of places I’d been and farms I visited. When I first saw Grant Wood’s work I felt a connection maybe because they felt familiar and maybe because I always wanted to be in his paintings. I eventually bought a Grant Wood art book, studied it a lot, and decided I wanted to try to paint like that myself. So I did and eventually it has become what you see today.

Post: Who else are you inspired by?

Moline: There are other Regionalist artists’ work I also really love. Marvin Cone’s sensual landscapes of that same area in Iowa are spectacular. The color and movement in John Steuart Curry and Thomas Hart Benton’s work I always find inspirational. Other non-Regionalist artists that stand out are the whimsy, detail, and subject matter of Charles Wysocki paintings. Some of my early favorites were the surrealist Artists Henri Rousseau, René Magritte and Salvador Dalí and the romantic look and thermal colors palette of Maxfield Parrish. I of course enjoy a wide range of artists going back to other centuries as well. While on my honeymoon back in 1980 I saw Botticelli’s large scale paintings and was in total awe. Recently while in Italy I saw again the work of Pinturicchio and his mythological scenes and detail in Sienna’s Duomo; I could have looked at that artwork all day long. Of course there are plenty of other artists to draw inspiration from including many peers but the above stand out in the top tier.

Post: What media do you typically work in?

Moline: My traditional style is I paint on illustration board. I generally do an acrylic airbrushed underpainting then go in with fine tiny acrylic brushes to finesse the art and add detail and texture.

Post: How did you get started in your illustration career?

Moline: I pretty much decided to freelance right out of my college years at The Minneapolis College of Art & Design. I was lucky to start out when I did. There was a lot of local work and I was able to get a representative early on. In the ’90’s after I had established a more consistent style and fine-tuned my skills, I then looked for a national representative and broadened my field.

Post: How is painting for yourself different from painting for a client?

Moline: I do enjoy both. I love the challenge of working with a client and the problem solving involved, whether it be a book or magazine cover, an editorial, a poster, map, or product design. I always love seeing the end result when a client is involved because I am working with other creatives and my work gets to be woven into a bigger picture. I also don’t mind a deadline; of course the longer ones are more welcome. When I work on a painting for myself it’s hard to know when to stop, and that can be a problem. Also when I have a set client there is incentive to get the artwork done because I get paid sooner. So that’s a big motivation as trite as that might sound. Of course painting for myself I only have myself to please and I can experiment and not have a client expecting that specific look they are after based on seeing previous work.

Post: What is your favorite thing about being an artist?

Moline: Honestly being my own boss and working out of my home and not dealing with a commute is the best. Working with so many wonderful creative people I’ve met along the way and that there is always a challenge and rarely a dull moment. Being an artist has made me grateful that I have a way to express myself and that it has allowed me to expand my imagination. Hopefully through my work I can move others emotionally and intellectually and to be able to share some of my inner world and imagination.

Post: What’s the most fun thing you’ve painted?

Moline: That’s a hard one to pick over the 40 years of painting. So I’ll give you a few that achieved a few levels of satisfaction. The Farmer’s Market Stamp project stands out…I loved the art director and I had a luxurious long deadline. It was first thought that I’d be doing some of my signature landscapes, but in the end I was painting every kind of fruit, vegetable, food, and plant you might find at a neighborhood farmer’s market. It was definitely a job that evolved over time, but I enjoyed the whole process and it also included a trip for the unveiling ceremony in Washington, D.C.

As far as landscape art goes I was lucky to work with HOK architects/engineering in the early ’90’s and did some big projects with them. The second was mural art for the new John Deere Pavilion in Moline, Illinois. The actual painting is a bit of a blur — the deadline was pretty fast considering the amount of painting involved, but the end results still please me to this day. I also fondly look back at an ongoing series I did for a high profile marketing group out in Hollywood called the Ant Farm. I created a group of ant characters for them that were pretty busy and active doing fun things mostly taking place out in L.A. Again, the clients were great to work with, too.

Post: What advice would you give to aspiring artists?

Moline: Patience and practice above all. You are not going to know your full potential, hidden talents, or fine tune your artwork right away. That takes time. Your artwork, as life itself, is an evolving process…and a gradual unveiling of yourself and your story. Don’t be afraid to experiment with different mediums and subject matter. You will make mistakes and you might disappoint those you work with now and then but you will learn from that. Don’t fear those periods of time when you don’t feel an ounce of creativity surfacing. When that happens, it will take time to observe and reflect and do whatever else you are being pulled toward…travel, read, relax and pick it up again when you are reenergized and the creative tap starts flowing again. Whatever you do don’t compare your work to others… if you are enjoying what it is you do and are growing as an artist, that is number one. Also accept that not everyone is going to like your art. Some will be critical, but if you love your work and you find a niche and even a few people love what you do as well, then you’ve made it. At that point smile and pat yourself on the back!

Post: Is there anything else you’d like Saturday Evening Post readers to know about your work?

Moline: Looking back on my career, a day that tickled me the most was when I was Googling some of Grant Wood’s work, my image came up and someone had mistaken it as his. Just last year I was asked to do a show down at the American Gothic House in Eldon, Iowa. That was another highlight of my career — to be standing in front of that house that had been parodied endlessly, and that my work that was on display inside was inspired by my favorite muse. I’ve told numerous people before that in fun I like to call myself Robin Wood. I think it has a nice ring.

To find out more about Robin and her work, visit robin-moline.pixels.com/.

Featured image: Robin Moline / SEPS.

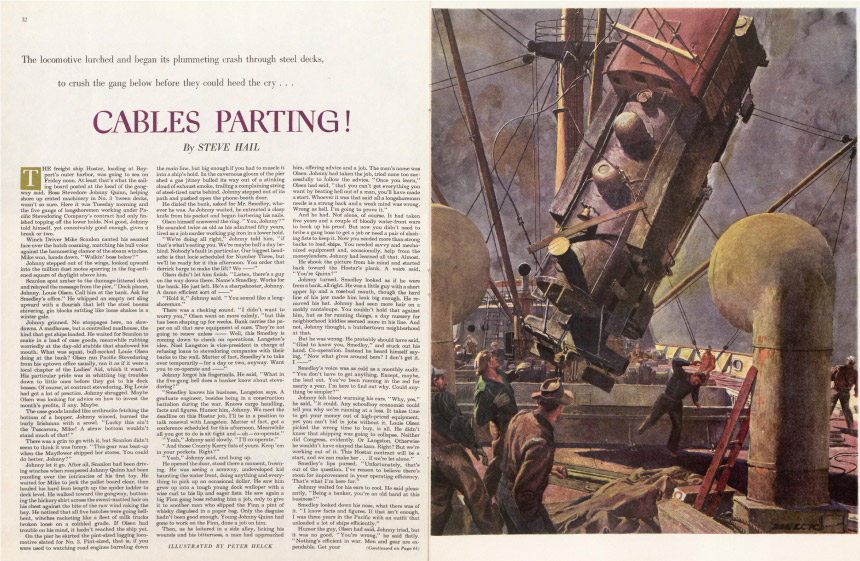

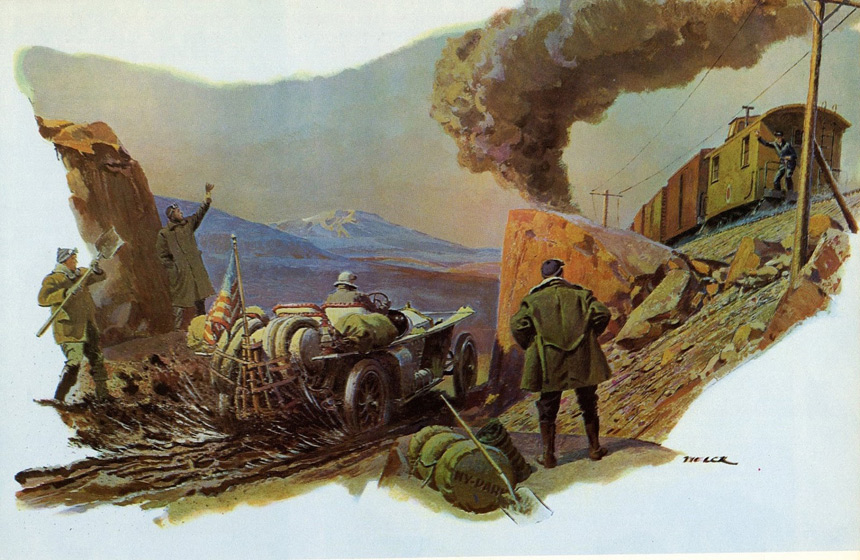

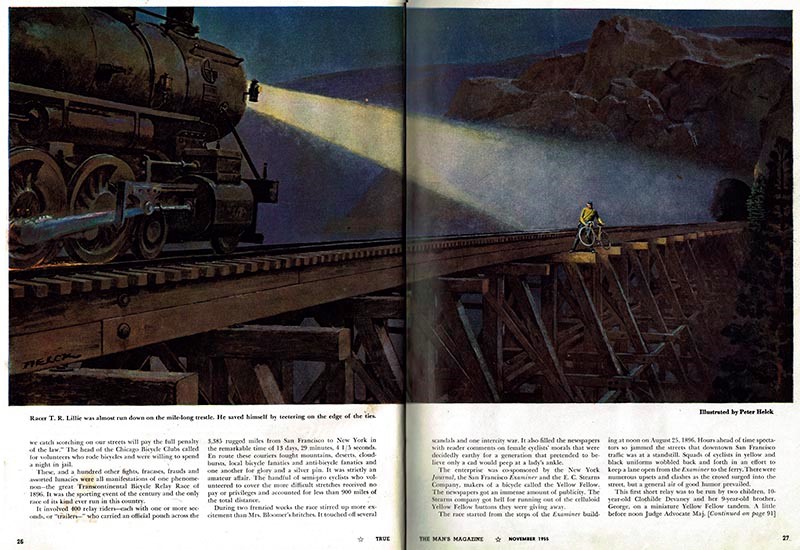

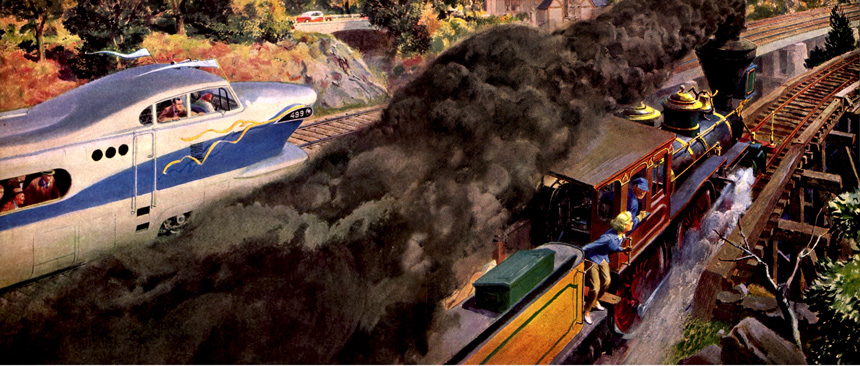

The Art of the Post: The Artist Who Loved Trains

Read all of art critic David Apatoff’s columns here.

Some artists specialize in painting landscapes. Some focus on painting portraits. Peter Helck painted trains.

Helck found as much excitement and inspiration in trains as other artists found in love stories. An article about Helck in American Artist magazine said, “he paints [railroads] with authenticity and with a dramatic power which expresses the romantic appeal these things have for him. He is passionately fond of locomotives; they are frequent subjects of his canvases.” Helck put it more bluntly: “[I’ve been] wacky over steam locomotives all my life.”

Helck was born in New York City in 1893. By the time he was 10 years old, he was spending his allowance each week on the model trains at Coney Island. His first art jobs were working for the art departments of local stores. As his reputation grew, he graduated to illustrating for magazines such as The Saturday Evening Post. Publishers spotted his special talent for painting machinery and industrial equipment, so when an assignment called for a picture of machines such as trains or old cars, Helck became the first artist they called.

At age 30, Helck moved to a large farm in Boston Corners, about 100 miles north of New York City. On his farm he had room to store his growing collection of battered old cars and tractors. When he wasn’t painting, he enjoyed working on them in his barn.

One of Helck’s favorite things about illustrating trains was that he occasionally wrangled permission to ride in the engine cab of real trains, sketching details and getting a sense for the experience. While illustrating the story “Thundering Rails” for the Post (March 27, 1948) Helck was able to ride in the engine cab of a train to Albany, New York.

He recalled breathlessly, “I got to work in an atmosphere gloriously dense with soot and smoke and generously affording the dramatic night lighting effects of which I never tire.” Of course, sometimes he forgot to ask permission. More than once he was kicked out of a train cab for trespassing.

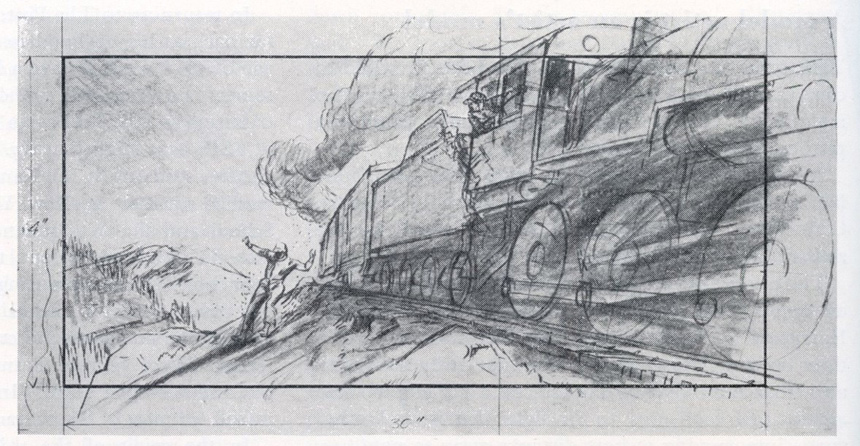

He also ran into trouble because he sometimes made the train, not the people, the star of his painting. As you can see from the following preliminary sketches for the story, “Screaming Wheels,” (The Saturday Evening Post, February 19, 1949) Helck started out by giving the starring role to the train, leaving a only a minor role for the human (who was supposed to be the center of the story).

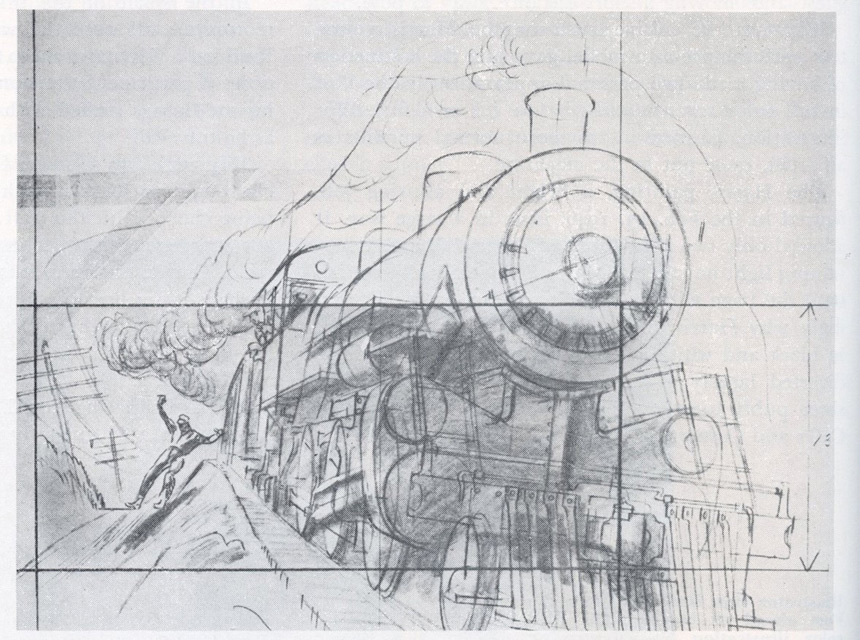

In the next drawing, Helck was nudged into increasing the importance of the man jumping off the train. Still, the train remained too prominent, so you can see how Helck cropped his beloved train to diminish its role even further.

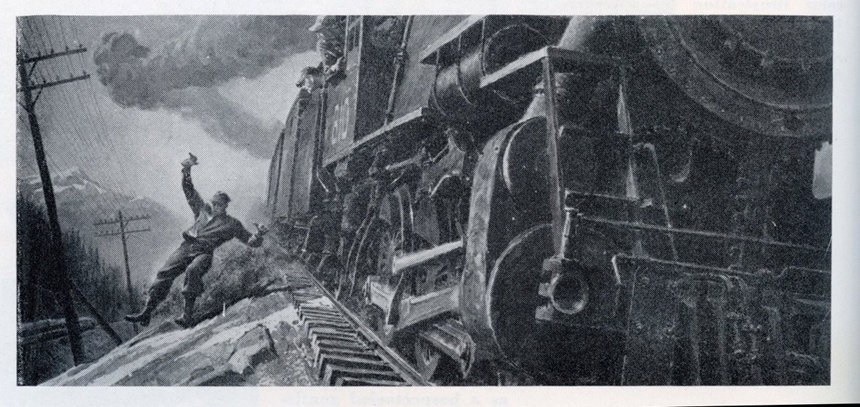

Here is the final version as it appeared in The Post, with the train veering off to the side and the man in the central role.

For another assignment, Helck painted a locomotive with smoke belching from the smokestack. When he delivered his finished painting, a junior account executive didn’t care for the dirty smoke, so he rejected the painting. He instructed Helck to take it back and paint a cleaner version minus all the smoke. However, when the art director saw the cleaner version, he was livid. He called Helck and asked him to restore the smoke, grumbling, “I was out of the office, sick, and that so-and-so went over my head. If I send it back will you put the guts in it again?”

Because Helck understood trains from top to bottom, he was even able to imagine how a falling locomotive would look. Obviously, no one could suspend a massive locomotive mid-air for Helck to paint, but he could project one in his mind. What other illustrator could pull off such a feat?

Most artistic traditions have been shaped over thousands of years. Artists in ancient Greece and Rome studied the human body and developed conventions that were passed down by artists through the ages. Renaissance painters made great strides in learning how to paint fabric and metal surfaces. Hundreds of generations have explored different approaches to painting the human face.

But trains were different. Trains were still relatively new when Helck was born, so he could not rely on generations of artistic solutions. Artists were still shaping the basic traditions for painting the speed, power, smoke, and other features of a locomotive. Helck’s love and enthusiasm for trains made him well suited for inventing and popularizing their images.

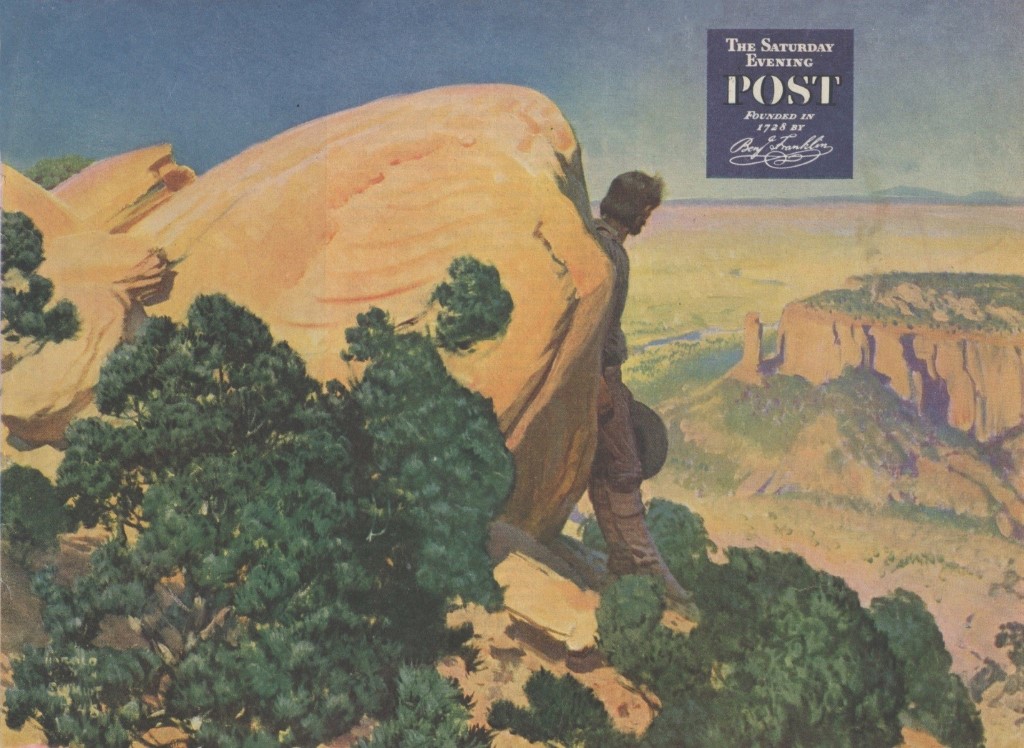

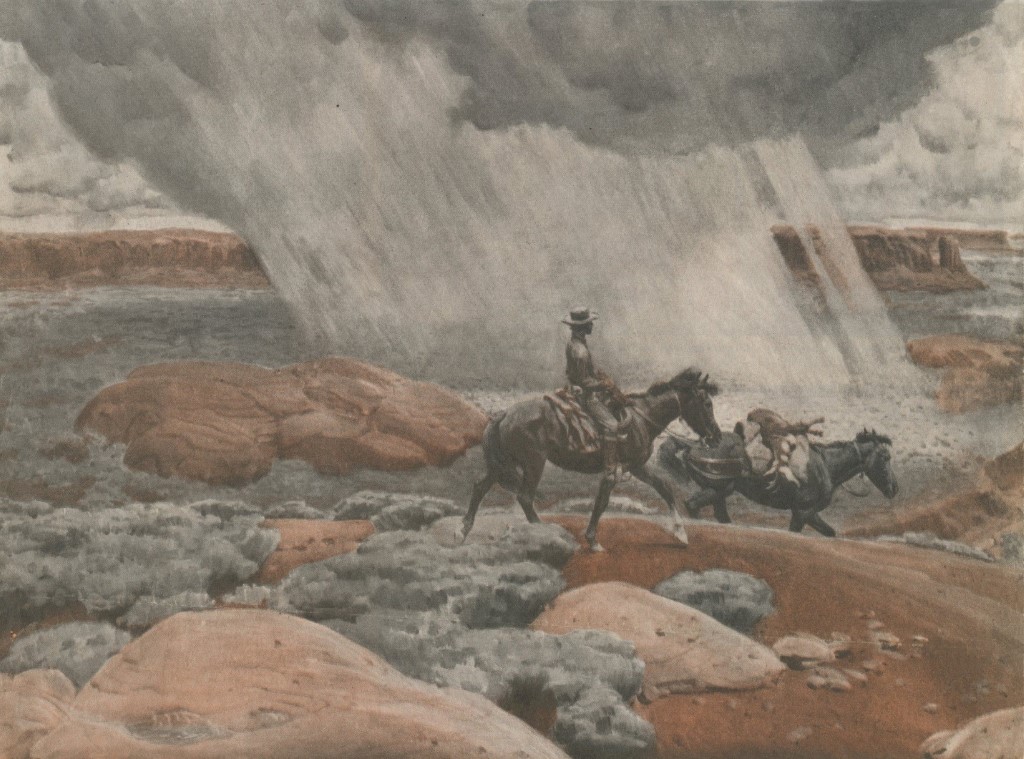

The Art of the Post: The Genuine Cowboy Artist

Read all of art critic David Apatoff’s columns here.

Cowboy stories were always popular with readers of The Saturday Evening Post. Several different artists were called upon to imagine the wild west for these stories, but none painted the old west as authentically as the great Harold von Schmidt.

Von Schmidt was a “leather-skinned Westerner with a lean, tanned face, a Will Rogers cowlick and eyes that seem to be focused on the horizon,” as described in his monograph from the Institute of Commercial Art. He was born in rural California in 1893, and, after being orphaned at age five, spent his early years exploring what he called “the last of the old west.” He recalled, “I had more freedom than most boys—the freedom of being forgotten…. Tactful forgetting is a fine thing for children. Being on their own gives them the initiative to succeed in a land of free enterprise.”

On his way to succeeding, von Schmidt worked as a cowhand, a lumberjack, a mule driver and a construction worker on a dam. He went down to the Mexican border where he met Pancho Villa’s ragged bandits. He learned about cattle and horses the hard way, as a working cowboy on long trail drives.

He also broke his neck twice, as well as half a dozen other bones, and dislocated his shoulder. On the good side, he once had lunch with the real Buffalo Bill.

Von Schmidt loved to draw and often kept a sketchbook with him. One day he met the famous western artist Maynard Dixon. Von Schmidt blurted out, “I’m trying to paint. I like the things you do.” Dixon did not give art lessons, but he was looking for a model and a studio assistant. He hired von Schmidt, and they soon formed a bond that changed the direction of von Schmidt’s life.

Dixon was impressed when he saw von Schmidt’s artwork. He said, “They’re a good deal better than I was doing at your age.” He spent a year coaching von Schmidt on how to improve his work.

In 1924 von Schmidt moved to New York in the hope of becoming a professional illustrator. He took his western artifacts and his ten gallon hat with him. In New York he met his wife, raised a family and became a highly successful illustrator.

For decades he was one of the lead illustrators for the Post. He painted a wide variety of subjects, but he was most famous for his illustrations of the old west. His pictures had an authenticity that you could not get from sitting in an art school; it was the kind of authenticity that you acquire from being thrown off a horse and landing on the hard ground.

He went on to become the president of the Society of Illustrators, vice president of the Artists’ Guild, and a founding member of the Famous Artists School. In 1959, he was elected to the Society of Illustrators’ Hall of Fame.

Later in life, after von Schmidt had moved to a large home in a prosperous Connecticut suburb, he looked around and remembered, “Once, I said to Maynard Dixon, who did so much for me, ‘Maynard, I’ll probably never have any money. How can I repay you?’ Dixon answered, ‘You can paint fine pictures and pass the word along.’” Von Schmidt tried to honor that standard throughout his career.