Horror for the Whole Family: Halloween Books for All Ages

Halloween is upon us once again. Last year, the Post looked at the question, “What’s the right horror film for the whole family?” And while staying in for movies is still an excellent choice for this spooky season, especially with the pandemic still present, films aren’t your only choice for eerie entertainment. So the new question becomes, “What are the right horror reads for the whole family?”

Every family’s view of content is different, and every family has a different standard for when it’s okay for the kids to indulge in scary fare. What we have here are some baseline recommendations, standout books that you might check out as starters, along with some appropriate ages. Again, your own idea of what’s appropriate and when may vary, but that’s why comment sections were created.

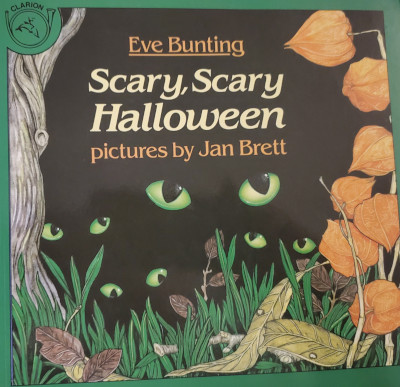

1.The Littles (9 and under): Scary, Scary Halloween by Eve Bunting and Jan Brett (1988)

Halloween-themed picture books abound, with lots of great, funny reads like Goblin Walk, but this one is a superlative effort from two huge talents. Eve Bunting has more than 250 books to her credit; she moves as easily from fiction to non-fiction as she does from picture books to novels. Jan Brett has been writing and drawing books for kids since the 1970s, and she’s received effusive praise for her lovely, intricate art. Scary, Scary Halloween brings them together in a delightful way, with rhyming verse and outstanding visual renditions of a scary Halloween night. An unseen narrator talks of monsters stalking through the neighborhood before the story takes not one, but two, surprise twists. It’s a great one to read to the little ones, and to have them read back to you as they get bigger.

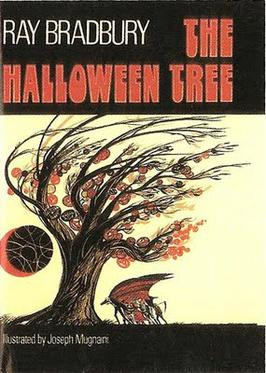

2. Kids to Tweens: The Halloween Tree by Ray Bradbury (1972)

Let’s be clear: Ray Bradbury’s The Halloween Tree is for EVERYONE, but it serves this particular demographic extremely well. Bradbury is, of course, one of the most exalted names in science fiction and fantasy, but he might also be the King of Halloween. His loving and nuanced takes on the holiday cause his name to appear repeatedly (and deservedly) on this list. The Halloween Tree is a touching story about friendship that also delves into the history of the holiday and its antecedent, Samhain. After a boy named Pipkin disappears, eight of his friends come together with the strange Mr. Moundshroud to travel through time to find their friend; along the way, they learn about the traditions of the Greeks, Romans, and Celts, visit medieval France, and witness what happens at Mexico’s Day of the Dead celebration. When the cost of saving Pipkin becomes clear, his friends come together for their friend in a moving finale.

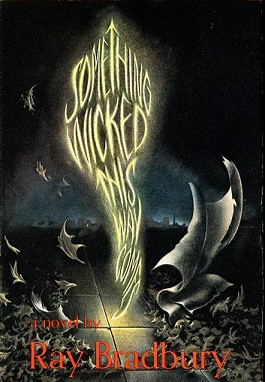

3. Teens: Something Wicked This Way Comes by Ray Bradbury (1962)

Today’s teens have access to a steady diet of horror material in both print and film; between libraries and streaming services, there’s not a lot that they haven’t already seen. That’s what makes Something Wicked This Way Comes special, in a way, because they might not have seen it. Bradbury’s 1962 masterpiece is all about the transition from youth to adulthood, while also baking in the regrets of age. When a strange carnival arrives in Green Town, Illinois on October 23, 13-year-old best friends Will Halloway (born one minute before midnight on October 30) and Jim Nightshade (born one minute after on October 31) are drawn into its orbit. At first, only Will and Jim seem aware of the unnatural events unfolding from the Cooger & Dark’s Pandemonium Shadow Show, but they find an unexpected ally in Will’s 54-year-old father. You can smell the autumn air in Bradbury’s rich descriptions of the season. The story, by turns wistful and terrifying, is one of the gold standards of dark fantasy. Teens can easily identify with the protagonists, as one of the primary forces in their own lives is the pull of adulthood.

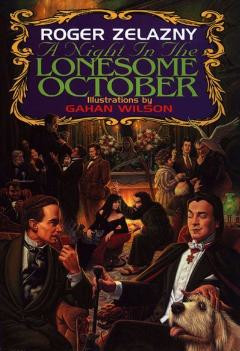

4. Adults: A Night in the Lonesome October by Roger Zelazney (1993) and October Dreams: A Celebration of Halloween (edited by Richard Chizmar and Robert Morrish, 2000)

A Night in the Lonesome October (not to be confused with Night in the Lonesome October by Richard Laymon, which is great in its own right) is creepy, funny, delightful, and demented. Zelazney was the celebrated writer of the bestselling The Chronicles of Amber series and dozens of other works; he won the Hugo Award six times and the Nebula three. 1993’s ANITLO was one his favorites of his own work; it was also his last novel, as he died in 1995. But what a great final statement it is. After an introduction, the 31 remaining chapters each take place on one day in October leading to Halloween in late 1800s London. The story is told from the point of view of Snuff, the canine companion and magical familiar of one Jack the Ripper. However, Jack is actually trying to save the world in a story that involves (either directly or by clever parody) the Lovecraft mythos, Dracula, Sherlock Holmes, the Wolf Man, the Frankenstein Monster, Rasputin, and more. The book is by turns haunting and hilarious, with Snuff and the other familiars alternately trying to help their masters save or destroy the world. Surprise alliances and betrayals abound, and it’s a real feat of imagination.

On the darker side, the 2000 anthology October Dreams: A Celebration of Halloween is simply one of the best collections about Halloween ever put to print. Collecting short stories along with non-fiction Halloween reminiscences by a murderer’s row of talent, the book includes the likes of Bradbury, Dean Koontz, Poppy Z. Brite, Christopher Golden, Jack Ketchum, Gahan Wilson, Richard Laymon, Dennis Etchison, Ramsey Campbell, Peter Straub, and many more. At over 650 pages, it’s a slab of fiendish goodness.

5. The Adult History Buff: Halloween: The History of America’s Darkest Holiday by David J. Skal (2016)

An October surprise bonus category! Yes, The Halloween Tree digs into the roots of the holiday, but this is a phenomenal book by one of the most authoritative writers on horror. Skal has written essential non-fiction like The Monster Show: A Cultural History of Horror, Hollywood Gothic, and Something in the Blood: The Untold Story of Bram Stoker, the Man Who Wrote Dracula. Here, he turns his keen insights to Halloween itself. Skal’s real talent lies in engaging a topic on both the macro and micro level, juxtaposing how that topic impacts the culture as a whole while also using laser-precise examples to show just how deeply that impact runs. Skal’s examination runs the gamut from the early Celtic days to a present where we (in non-pandemic years) spend about $9 billion celebrating the holiday.

6. Grandparents: Ghost Story by Peter Straub (1979)

This one goes off theme just a tiny bit, but bear with it. Yes, Ghost Story takes place across multiple time periods with one of the most climactic sequences occurring during a blizzard. But it is one of the grand champions of scary storytelling, and the initial protagonists are a group of older gentlemen and one gentleman’s wife. With many mature main characters and Straub’s deep appreciation for the canon and history of American horror (references to Nathaniel Hawthorne and Donald Wandrei abound, and nods are clearly made to George Romero and Straub’s pal Stephen King), Straub crafts a particularly literary story that thrives on human emotion. There is some really dark stuff, but there are also seeds of hope, especially when the older men reach out to two other protagonists (one much younger) to help them navigate the terror that has them under siege.

And there you have it: like the film list, it’s a list to get you started (and to start discussions). Enjoy this very strange season, get lost in the books that you intend to read, and maybe, just maybe, leave a light on.

Featured image: Marsan / Shutterstock

20 Years Later, Stephen King’s On Writing Remains a Career High

It’s frankly impossible to overstate the influence of Stephen King on American popular culture. Sure, we all know that he’s the King of Horror and that he’s sold over 350 million books and that his work is regularly adapted into film and television and comics. His impact and influence hasn’t just been exerted on the field of horror and fantasy, but on so-called “literary” writers like Victor LaValle, Sherman Alexie, Karen Russell, and Haruki Murakami. With more than 60 novels, five non-fiction works, and over 200 short stories to his credit, it might also be impossible to select the quintessential King book. However, if you had to pick the work that says the most about King himself, it’s almost certainly On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft. Part origin story, part how-to manual, and part harrowing depiction of King’s recovery from a near-fatal accident, the widely praised book is celebrating its 20th anniversary with a new edition that includes contributions from his sons, the writers Joe Hill and Owen King. Now, in the week of King’s 73rd birthday, here’s a look at what makes On Writing an Entertainment Weekly New Classic, a Time Top 100 Nonfiction book, and The Cleveland Plain Dealer’s “best book about writing, period.”

Stephen King presents a wide-ranging talk about writing (Uploaded to YouTube by Politics and Prose)

The first major section of the book is called C.V. (the abbreviation for curriculum vitae, which is a look at one’s body of work). In this first of two extensive autobiographical passages, King deals comprehensively with his difficult youth, his discovery of his passion for writing, falling in love with wife (the novelist Tabitha King), breaking through with Carrie, his early fame, and his subsequent battle with alcoholism and substance abuse (which was extensive enough to require an intervention; King notes that he doesn’t remember writing all of Cujo). Each story is a block in the foundation of King’s voice. You gain an understanding of many of the levers that move his prodigious output. King also notes the self-involvement (or even obsession) that writers can fall prey to and relates the story of two desks that he’s used for writing, allowing it to become a metaphor for one simple idea: “Life isn’t a support system for art. It’s the other way around.”

The backbone of what you might call the instructional part of the text is the middle, with section names like “What Writing Is,” “Toolbox,” and “On Writing.” The thing that really separates On Writing from other how-to books about the field is King’s approach. While there’s a degree of “this is how you do it,” King readily admits throughout that, more or less, “this is how I do it,” noting frequently that the specifics of process change for each writer. He’s not giving you step-by-step Ikea instructions; he’s giving you a route while acknowledging that there are still many other routes that will get you to the destination. His tone is one of encouragement, but also one of caution; King believes that talent is an unteachable intangible, but he also believes in craft and improvement. That’s part of what makes the “Toolbox” section critical, in that he emphasizes the tools that all writers should have, particularly vocabulary, grammar, and style.

Stephen King talks about his writing process (Uploaded to YouTube by Bangor Daily News)

The middle portion of the book draws much attention from critics because of its plain-spoken approach. King simultaneously demystifies that process of writing while also attributing some of the success of it to “magic.” But King seems to impart that you don’t get to magic without knowing the tools, and that’s important. Writers need to read, they need time to form, and they need to work. King isn’t King just because of his fame or money or output, it’s because he works. Every day, the Sun comes up, babies are born, and Stephen King is writing something. There’s optimism in his instruction, almost an “if I can do it, you can do it” kind of humbleness, even as he points out that this stuff isn’t as easy as he makes it look. He’s not teaching you how to become a brand name, but he’s teaching you about the discipline.

“On Living: A Postscript” sees King dealing with the accident that nearly killed him in 1999. As he was out for a walk, King was struck by a van driven by a distracted driver. He suffered grave injuries; among them, his leg was broken in nine places, his knee was basically split, his right hip was fractured, he had four broken ribs, and his spine was “chipped in eight places.” As terrible as that sounds (and it was terrible), King somehow landed in the perfect spot after the impact threw him several feet through the air. If he had deviated in course to the left or right, he likely would have suffered fatal traumatic head injury due to rocks or railing. As it was, he was in the hospital for three weeks and went through multiple surgeries to address his injuries. King then confronted something else that was harrowing in its own right: getting back to a writing routine after that, something that Tabitha King played a crucial role in achieving. Obviously, King succeeded, but the difficulty that he had is palpable on the page.

Stephen and Owen King talk about collaborating (Uploaded to YouTube by Good Morning America)

In the anniversary edition, King’s sons offer contributions. Joe Hill has built his own bestselling brand in the horror genre with novels, comics, and short stories, while also seeing film and television adaptations of his work, notably Locke & Key and NOS4A2. Owen King is also a prolific writer of novels, short stories, and articles who in 2017 co-wrote the novel Sleeping Beauties with his father. Hill’s contribution is his transcript of a talk with his father at Porter Square Books from 2019, while Owen King’s piece reprints his article “Recording Audiobooks For My Dad, Stephen King” from the New Yorker site. Both segments add insight to the process that bring some extra color to the book overall. There’s also an updated “Reading List” from King himself, packed with books that he simply thinks that writers should read, which contains items perhaps expected (Golding’s Lord of the Flies, Conrad’s Heart of Darkness) and unexpected (Anne Proulx’s The Shipping News, Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited).

As a writer, King’s impact is immeasurable. Heavily awarded over time, King can count a National Book Foundation Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters, a World Fantasy Award for Life Achievement, and a National Medal of Arts among his accolades. On Writing is certainly a departure from expectations, but it remains thoroughly King. It’s considered a high-water mark for a book of its type because articulates big ideas in a way that anyone can understand, and it offers encouragement in a discouraging profession (and world). King insists that all writers need to read; On Writing remains a great place to start.

Featured image: George Koroneos / Shutterstock

Top 10 New Books for Fall

Fiction

Migrations

by Charlotte McConaghy

Franny goes to the ends of the earth tracking the last migratory pattern of birds and will stop at nothing to find them, and herself. This novel moves back and forth in time as she runs both away from her past and straight toward it.

(Flatiron Books)

Sweet Sorrow

by David Nicholls

Charlie Lewis is in a dark place, but that doesn’t explain why the 16-year-old joins a theater troupe putting on Romeo and Juliet. Told in flashbacks by his adult self, the secret, and a tantalizing love story, slowly unfolds.

(Houghton Mifflin Harcourt)

The Wife Who Knew Too Much

The Wife Who Knew Too Much

by Michele Campbell

A fast-paced, frothy thriller set among the rich and not-so-rich in the Hamptons. Filled with twists and turns, social scandals, and a killer, this novel is a perfect, gripping page-turner.

(St. Martin’s Press)

Luster

by Raven Leilani

This debut novel tells the story of a 29-year-old Black woman who gets involved with an older, married white man. As the plot zigs and zags, this deeply funny and wry book investigates race, art, and identity.

(Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

The Evening and the Morning

by Ken Follett

Set in England at the dawn of the Middle Ages, this prequel to Follett’s bestselling The Pillars of the Earth is an addictive tale of rivalry and ambition, love and hate.

(Viking)

Nonfiction

Caste

by Isabel Wilkerson

Using individual stories to lay out her expansive and historical argument — that we aren’t just divided by race, but by caste — Wilkerson reaches back into history to confront painful truths. This book is nothing short of an awakening.

(Random House)

Wandering in Strange Lands

by Morgan Jerkins

The author of This Will Be My Undoing sets out to find her family’s roots. In so doing, she paints a larger portrait of African American displacement and disen- franchisement during the Great Migration and its effects on her.

(Harper)

The Journalist

by Jerry A. Rose and Lucy Rose Fischer

This memoir gives readers a view into the early days of the Vietnam War from one of the first reporters who covered it — from being caught in firefights to scooping news stories to dodging the secret police.

(SparkPress)

What Can I Do?

by Jane Fonda

In a memoir that functions as a call to action, Fonda takes readers on her journey of activism, including her conversations with scientists and regional community organizers that led to Fire Drill Friday, her weekly climate change demonstrations.

(Penguin)

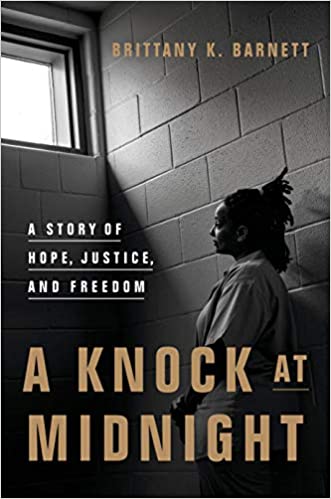

A Knock at Midnight

by Brittany K. Barnett

This vital and deeply personal memoir follows a young Black woman who becomes a lawyer to fight for people unfairly incarcerated for minor drug charges and faces a justice system all too happy to throw people’s lives away.

(Crown)

This article is featured in the September/October 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Prostorina / Shutterstock

Six Things You Didn’t Know About To Kill a Mockingbird

Harper Lee’s classic novel To Kill a Mockingbird went on sale 60 years ago this week. The two-part structure of the novel deals with the Alabama childhood of Jean Louise “Scout” Finch and the challenging case taken on by her lawyer father, Atticus. It’s one of the most widely-read books in the United States and a staple of middle and high school curricula. In honor of the six decades that the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel has been a cultural touchstone, here are six things you didn’t know about To Kill a Mockingbird, its writer, and the award-winning film.

1. The First Draft Is an Entirely Different Book

Lee lived in New York City in the 1950s, working in reservations for British Overseas Airways. Her childhood friend, the writer Truman Capote (more on him later), connected her with an agent in 1956. Lee’s friends supported her for a year so that she could write her book; the novel, Go Set a Watchman, sold to the publisher J. B. Lippincott Company. Editor Tay Hohoff felt the book had promise but also that it needed more work. For over two –and –a half years, she worked with Lee to transform Watchman into the book that would be To Kill a Mockingbird. In a twist that could only happen for a book as famous as Mockingbird, that first draft, Go Set a Watchman, was released as its own book in 2015. HarperCollins, who published Watchman, faced harsh criticism from several quarters for marketing that positioned the book like a sequel rather than a first draft; they drew additional fire for the perception that Lee had been manipulated into allowing the release just a few weeks after the death of her primary caregiver, her sister Alice.

2. Harper Lee, Truman Capote, and Kansas

Truman Capote wasn’t just Lee’s childhood friend; he was the inspiration for the character Dill in Mockingbird. In 1959, as Lee waited for the publication of the novel the following year, she went with Capote to Kansas on a research trip. Capote was pursuing an article on the murder of a farming family, the Clutters. The article eventually grew into Capote’s seminal work, the 1966 book In Cold Blood. Over the years, that trip has taken on an almost mythic status in the literary world. It’s been depicted in two films: Infamous, based on George Plimpton’s book Truman Capote: In Which Various Friends, Enemies, Acquaintances, and Detractors Recall His Turbulent Career and starring Toby Jones as Capote and Sandra Bullock as Lee; and Capote, based on Gerald Clarke’s biography of the same name and starring Phillip Seymour Hoffman and Catherine Keener. The trip was also depicted in the acclaimed graphic novel Capote in Kansas by writer Ande Parks and artist Chris Samnee.

3. Lee Received Presidential Material

Harper Lee Receives the Presidential Medal of Freedom. (Uploaded to YouTube by C-SPAN)

It’s not unusual for writers to be awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom or the National Medal of Arts. It’s very unusual to receive both on the strength of one book. For 55 years, Lee had only one novel published (and some argue the validity of Watchman as a novel at all, given its odd draft status). However, it’s a tribute to the impact of the book that Lee received the Medal of Freedom from George W. Bush in 2007 and the Medal of Arts from Barrack Obama in 2010.

4. The Novel Continues to Face Challenges

Despite the novel’s iconic status, it remains one of the most challenged by various groups that want it removed from school curricula or public libraries. It was the seventh most-challenged book as recently as 2017, according to the American Library Association. As early as 1966, the book received challenges on the basis of content related to rape. Despite the anti-racism messaging prevalent in the book, it’s been challenged for containing racial epithets. Mockingbird also draws fire for its inclusion of profanity not related to race.

5. Atticus Finch Set a High Bar

The trailer for To Kill a Mockingbird. (Uploaded to YouTube by Movieclips Classic Trailers)

Atticus Finch has been praised as a both a literary hero and, as portrayed by Gregory Peck, a hero of film as well. Peck won an Academy Award for his work in the 1962 film. The American Film Institute’s 2003 list, “100 Heroes & Villains” named Finch as the greatest hero in American movies. In 1993, DC Comics writer and artist Dan Jurgens used a scene in Superman #81 to cement the notion that the adaptation of the novel is Clark Kent’s (and therefore Superman’s) favorite movie. Over time, some writers have questioned the lionization of Finch, mainly noting that he takes on a racist in the courtroom, but does little to take on the racism endemic in their hometown.

6. The Mystery of Boo Radley

The mysterious nature of Boo Radley in the novel and film has made him something of a cult character and a shorthand reference for an unseen figure in a narrative. The role of Radley marked the film debut of celebrated actor Robert Duvall, who has since been nominated for seven Academy Awards (winning one for Best Actor in Tender Mercies). British band The Boo Radleys took their name from the Finch’s neighbor. And Bruce Hornsby’s song “Sneaking Up on Boo Radley” is about the events of the novel related to the character.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Coming Around Again: The Longest Running (and Longest Gaps Between) Hits

To say that 2020 has been an odd year would be an understatement on the order of “The Beatles were mildly popular.” One of the places that the strangeness of our lockdown year has been reflected has been at the movies. With regular theaters closed, drive-ins surged, frequently playing older films. That resulted in the unusual case of 1993’s Jurassic Park hitting the top of the box office again in June. That phenomenon leads to the following questions: what are the biggest gaps between chart toppers, whether at the box office, the record charts, or elsewhere, and what are the film and TV series that have stuck around the longest?

1. When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth

Jurassic Park stomped to #1 for three weeks upon its initial release in 1993. On June 22nd, lifted by drive-ins, the film took the top spot again 27 years after its original ride. Gone with the Wind remains the all-time box office champion if you adjust for inflation, and the 1939 film had three official re-releases (1989, 1998, 2019), but none of them cracked the #1 spot.

2. Cockroaches and Cher

There’s an old joke that goes that if there’s ever a nuclear war, all that’s left will be cockroaches and Cher. While that’s a loving, tongue-in-cheek tribute to the star’s longevity and resiliency, it also has a ring of truth to it where the charts are concerned. Cher hit #1 for the first time in August of 1965 with her then-husband Sonny Bono on their classic “I Got You Babe.” After a continuous run of hits throughout the rest of the 1960s, the 1970s (with three solo #1s), the 1980s, and the 1990s, Cher took “Believe” to #1 in March of 1998. That’s an amazing 33-year-and-seven-month gap between her first #1 and her most recent #1.

Other prodigious gaps between first and most recent #1s have been held by George Harrison (23 years and 11 months between “I Want to Hold Your Hand” as a Beatle in 1964 and “Got My Mind Set on You” in 1988), The Beach Boys (24 years and 5 months between “I Get Around” and “Kokomo”), Elton John (24 years and 8 months between “Crocodile Rock” and “Candle in the Wind 1997”) and Michael Jackson (25 years and 8 months between “I Want You Back” with The Jackson 5 and “You Are Not Alone”).

3. His Name is Series, Longest-Running Series

While the overall continuity of the James Bond series is in question, everyone generally treats the films as if they’re part of an ongoing mega-series. It’s the third-highest grossing franchise in movie history, behind only the Marvel Cinematic Universe and Star Wars. But the biggest weapon that Q never designed is Bond’s insane longevity. The first film, Dr. No, was released in October of 1962. If No Time to Die keeps its adjusted November 20, 2020 release date, then that will be 58 years and one month between the first and most recent installments of the series.

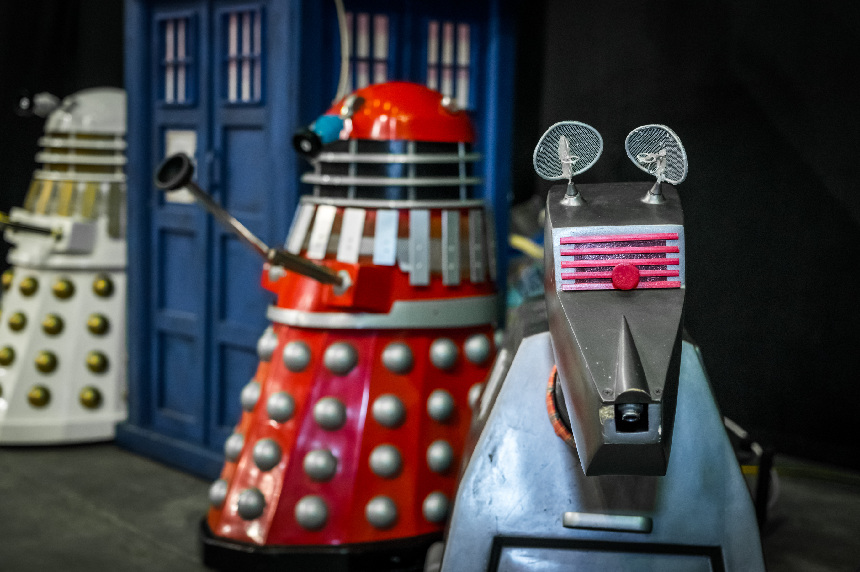

4. Call The Doctor!

Another British favorite that will seemingly go on forever is Doctor Who. There’s no question about Who continuity; everything is fair game, particularly when your main character is a regenerating Time Lord that is simply the same character in a new form with each re-casting. The Doctor’s first adventure aired in 1963. The original series ran uninterrupted until 1989. A TV film aired in 1996. The series restarted in earnest in 2005 and has been running ever since. The most recent season ended in March of this year. While the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic has put production dates everywhere in question, a special, “Revolution of the Daleks,” should air around the holidays, and the next season is generally expected to air beginning in 2021. If you simply use today as the metric for how long the single continuity of Doctor Who has been running, that’s 57 years of adventures in space and time.

5. Hang on, Marshal Dillon; Detective Benson Is Here

For many years, the issue of the longest-running drama on prime time American television wasn’t a question. That was Gunsmoke, which ran from 1955 to 1975. In 2019, that record was passed by Law & Order: Special Victims Unit, which started in 1999 and is ongoing at present; in fact, NBC has already given it a blanket renewal through a 24th season. The longest-running prime-time program overall is animated comedy The Simpsons, which launched in 1989 and is still running.

On the daytime side, the Guiding Light still holds the record for longest running daytime drama with 57 years on the books at its 2009 sign-off. That record will fall to General Hospital in the very near future. Had it not been for the interruption in production brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic, GH would have passed it this summer. At the moment, a hard pass date can’t be established until production resumes.

6. Seriously, I Was Writing the Whole Time

Some writers seem to function at an inhuman level of output. For every George R.R. Martin, who takes years between A Game of Thrones installments, you have his pal Stephen King, who has averaged 1.4 novels a year since 1974 (plus 11 short story collections, 19 screenplays and five nonfiction works). Then you have the entirely opposite end of the spectrum where dwell writers that have a literal lifetime between their first and second novels. The big winner there is Harper Lee; 55 years passed between the release of To Kill a Mockingbird and Go Set a Watchman. On the technical level, the issue of what to call Watchman exactly is the subject of some debate; yes, it’s a novel, but it’s also really the first draft of what would become Mockingbird.

If you’re looking for the longest gap between an original novel and its sequel, then King might hold the record. It’s true that 59 years passed between the publication of Upton Sinclair’s King Coal and the follow-up The Coal War. However, Sinclair finished the sequel in 1917; the publisher didn’t want to put it out and it sat until 1976, eight years after Sinclair’s passing. King’s gap comes between the 1977 publication of The Shining and its sequel, 2013’s Doctor Sleep, which hit stores 36 years later.

7. Another Day in the 87th Precinct

When it comes to the longest-running series of novels, there are quite a few qualifiers involved. Some novels are franchises given over to other writers, or are based on characters owned by companies rather than individuals. That might account for characters like Doc Savage or Remo Williams/The Destroyer, that have hundreds of novels under their fictional belts. Then you get into series, like Terry Pratchett’s Discworld, with 40 books, or Agatha Christie’s 38 books centered on Hercule Poirot, or the exploits of Rex Stout’s Nero Wolfe in 49 books. Erle Stanley Gardner produced 82 Perry Mason mysteries between 1933 and 1973.

But the longest sustained series by one author appears to be the 87th Precinct series of novels by Ed McBain, which is the pseudonym of Evan Hunter. Between 1956 and 2005, McBain put out 54 novels that take place in one overarching continuity. Set in the city of Isola, a fictional analogue of New York City, the novels follow the cases of the Precinct, most of which involve Detective 2nd Grade Steve Carella.

It seems appropriate to give a mention here to Sue Grafton. From 1982 to 2017, she published “The Alphabet Mysteries,” a series featuring her detective Kinsey Millhone. The books were designed to be a series of 26, one for each letter of the alphabet (A is for Alibi, etc.). The series ran for 35 years. Unfortunately, Grafton passed away in 2017 before beginning the planned Z is for Zero. As opposed to writers like Robert Jordan, who worked with others to see that his Wheel of Time series would be completed after his death, Grafton disdained the idea of having a ghostwriter finish the series. In the Facebook post that announced her mother’s passing, Grafton’s daughter Jamie wrote, “Many of you also know that she was adamant that her books would never be turned into movies or TV shows, and in that same vein, she would never allow a ghost writer to write in her name. Because of all of those things, and out of the deep abiding love and respect for our dear sweet Sue, as far as we in the family are concerned, the alphabet now ends at Y.”

Featured image: Shutterstock

When Someone You Love Is Behind Bars

For many Americans, the crisis of mass incarceration is a daily encumbrance. These are the children, wives, boyfriends, grandmothers, nephews, and friends of the 2.3 million people who are locked up in the United States. Journalist Sylvia A. Harvey has spent time with family members of incarcerated people — having been a family member of one herself — and her recent book, The Shadow System: Mass Incarceration and the American Family, tells their stories in intimate detail.

Although many in this country still look at full prisons and see criminals rightly serving their sentence, Harvey maintains, as many others have, that the price we pay for so much incarceration can be tracked through generations of wrecked communities. She writes:

When people are incarcerated, we as a society rarely consider the lives — and the people — left behind. But their former lives don’t simply vanish. For their children, those prisoners remain parents. The collateral effects of mass incarceration cut through the immediate fabric first, then penetrate the entire extended family for generations. The most fragile of those impacted are the children.

If you’ve never met someone affected by America’s prison system, Harvey believes you should read her book. In our interview, she paints a picture of what life can look like when someone you love is behind bars. The costs, financially and emotionally, of the highest incarceration rate in the world are paid heavily by the families of the disproportionately black and poor prison population. Harvey says that this isn’t inevitable, and that the patchwork of policies and programs around the country often point to what works better, if only we can find the political will to act on it.

The Saturday Evening Post: In your book, you write about how you’ve been affected personally by incarceration. Can you talk about that?

Sylvia A. Harvey: Yeah, I experienced parental incarceration from my father for about 27 years in different California prisons. What’s been important for me, having that experience, is being able to utilize that to see what’s happening around the country to 2.3 million families, people who are directly impacted now. My father spent 27 years in prison, and that’s been significantly helpful in thinking about how policies need to change and how families are being impacted.

SEP: How did you find the families whose stories you featured in this book?

Harvey: That was actually a task. What I started to do was to call organizations from each state that was of interest for some reason. So, I picked Mississippi because of what’s happening there in terms of race relations. It is not a progressive state, so to speak. So, to look at incarceration and its impact on families in a conservative state, in a place like that, it meant calling any organizations that worked with families impacted by that. There weren’t very many programs, so it was difficult. So then I called local churches, local organizations. It was literally looking at what kinds of organizations were in place at the grassroots level.

Florida was a little bit easier because they had more organizations that worked with this demographic. I started to go along on some of the visits they had in Florida with the Children of Inmates program, going along on some of those trips and sitting in the visiting room. From doing some of that preliminary reporting, I was able to determine which families were most suitable for the book.

SEP: Could you give a rundown of the three families you covered in The Shadow System?

Harvey: In Miami, I looked at a young man, a young black man, who has a murder conviction. So, what does that mean for a young person in Miami to have this kind of conviction, and what does that mean for his daughter? In Jackson, Mississippi, now we have a family where the father has been incarcerated for 39 years. So, what does it look like to have a life sentence and to have served almost 40 years of that sentence? Being able to look back on how that manifests in his family, his three children who are all black boys. In Louisville, Kentucky, I was focusing on returning citizens, and predominately white women who were impacted by the opioid epidemic, as they returned home. So, looking at issues across the country with different demographics.

SEP: What surprised you about how other people who have been affected by incarceration live and cope with that?

Harvey: I think, the availability of resources. So, in different states you have different resources. That was — I wouldn’t say shocking — but why I decided to write the book in this way, to focus on states that are not represented often, the states we don’t really think about. It was surprising for me to see exactly how incarceration manifests. Like, how you could serve as much time as the man in Mississippi did and be able to look at other states where they’re releasing people.

I was surprised by the difference in legislation, the difference in sentencing, and the difference in resources. In Jackson, there weren’t very many resources, but if you go to Miami, there’s this program where they’re literally taking these children and their families all over the state to visit their parents in prison four times a year. This is a resource that is state-funded, so why doesn’t that exist in other parts of the country? There’s a disparity in resources available, disparity in sentencing, disparity in visitation, depending on where you are in the country.

SEP: How did visitation differ from case to case, and what does that process look like?

Harvey: In the book, my focus is on family visitation. So, family visitation was something that was taking place in Jackson, Mississippi. Family visits in that state were three to five nights, where you could literally go on prison grounds in a small apartment or trailer that’s sort of set up to mimic the idea of being home. That’s the kind of visitation I focused on because it’s obviously the most progressive visitation, and I wanted people to be able to look at that and see what that means. It means these families are able to go and feel like they’re at home again. The mother who has three children and a husband who’s been incarcerated for 39 years is able to continue to build with her partner by having these visits. That’s pretty significant. I think it’s important to be able to look at that and see what that means, what that feels like, and why it no longer exists in some states but still exists in others.

SEP: What does visitation look like in other places where they don’t have those types of programs?

Harvey: It really depends, so in some states you’ll have visitation that is behind the plexiglass, no contact, and in some places you’ll have video visits. A lot of jails are turning to video visits only, which means you’re going to the jail facility but only using video. Some visits allow contact, but it’s limited contact, so you go to the jail or prison and, for the first, maybe 15 seconds, you’re able to greet the person, give them a hug or kiss or whatever, but there’s a limitation on the physical contact you can have. Some facilities will allow you to maybe hold hands but nothing more than that. It really differs from state to state, city to city, jail to prison, it’s a broad spectrum of what can and cannot take place.

SEP: You write about the people in Kentucky who have been affected by the opioid epidemic. Can you talk about how that crisis has been handled differently than drug epidemics of the past?

Harvey: Yeah, I would say that the 1980s war on drugs — all of that legislation — literally ensured that people of color were under attack. From that alone, they were overrepresented in jails and prisons. The Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 was something that really put racial minorities in a chokehold. The thinking of criminality, the idea of looking at it as something people were doing and not something happening to people. We weren’t thinking about it in the context of a health crisis. And now, we’re looking at the opioid epidemic as a health crisis. Like, “how do we fix this? How do we help people?” That was not the narrative when we had the war on drugs during the crack epidemic. It was “let’s lock all of these people up,” and I think that’s been a huge distinction.

SEP: How have companies been profiting off the increase in incarceration?

Harvey: Financial exploitation of families by the prison industry is huge. We see that in phone calls, e-mails, videos, these are all services that we on the outside are able to access quite easily. That is not the reality for people who are incarcerated. They have to pay a really high rate for these things. In Jackson, one of the families paid $6.99 for her video call that was 15 minutes. What does that mean for those families to pay that every time they want to interact with their incarcerated loved one? In some counties, it’s up to 25 dollars for a 15-minute phone call. That exists. It’s a huge industry. The going rate for hundreds of counties is 15 to 18 dollars for a 15-minute phone call. Some of these costly rates are driven up hundreds of millions of dollars by concession fees. We would call them “kickbacks.” The phone companies are paying local and state prison systems in exchange for these exclusive contracts. So, as long as they’re getting this kickback, why give them free or cheap ways to communicate?

And on top of that, we also have commissary. This is like the prison retail market. So, inside these prisons, people still need access to things. If you get a small bar of soap or if you get limited food during lunchtime or dinner, you order extra from the commissary. It’s not always that the commissary is significantly higher, but it’s high when we think about the prisoners who are paying for this. If you make four dollars a day and then you have to pay four dollars for a fungal cream, then that is exorbitant for you. Families spent $1.8 billion on commissary in a year most recently, and that’s a lot of money for families to spend. [Prison Policy Initiative found that American families spent $2.9 billion on commissary and phone calls yearly in 2017.]

I think as long as that is happening, then families will be exploited. We have to think about why it is that we can charge that. We say, to a degree, that “they can’t have cell phones” because “we don’t know what they would do with these cell phones,” but a lot of this is just financial exploitation. Private companies have found a number of ways of making sure it’s profitable. These families want to stay in touch, and if they have to go in debt trying to, that’s what you do.

SEP: Who do you think should be reading your book?

Harvey: I would say, people who are not familiar with the concept of mass incarceration and how it is impacting this country; not only people who already care about incarceration. Everyone who wants to be informed and be good citizens should be reading this book. As humans, we need to be thinking about what our country is doing, in terms of policy, that is impacting specific demographics. We need to be thinking about why it’s impacting black, brown, and poor people at such a high rate, and what that says about how we feel about those people. It needs to be read far beyond the advocates, far beyond the reformists, far beyond the directly impacted, but by those who are not familiar with what is happening but should be. We can’t continue to allow willful ignorance; I think everybody needs to demand that we have an equitable system in this country. Everyone should be reading it, and especially those who aren’t familiar with how morally bankrupt our system is.

It’s easy to give out statistics, like, “hey, 2.3 million people are incarcerated, 555,000 of those people are locked up pre-trial, which means they can’t go home because they don’t have the money,” but if you haven’t had a friend or family member face that, then you don’t understand that. So it’s easy to say that, but what does that mean? What does that look like? If I tell you a story about a young man who faces this and what that means for him, then we’re like “huh, that that’s how that works.” So I think it’s important to use narrative and storytelling to illustrate how policy is impacting people. That way, we’re able to connect to the person and understand the policy behind that.

SEP: Speaking of pre-trial, you write quite a bit about people serving long prison sentences, but we have seen jailing in the short-term increase a lot in this country, especially in rural areas.

Harvey: In Louisville, a lot of the women I interviewed were actually from eastern Kentucky. So, it’s very rural, and there’s not a lot of access to rehabilitation programs or drug or alcohol treatment that goes beyond the seven days, so they were jailed and then released to this program, The Healing Place, that allowed them to have a longer stay to really deal with this drug or alcohol issue. One of the young women in the book served 18 days, and the 18 days she served in jail impacted her heavily because while she was in jail, her children were put into foster care. Once this woman got out of jail, she figured she’d pick up her kids, but you can’t just pick up your kids once they’re in the child welfare system. She spent less than a month in jail, but once she got out she had this huge battle ahead of her, because we’re looking at the Adoption and Safe Families Act, and how it impacts families of people who are incarcerated. So, she was now up against this clock. So they gave her a case plan saying she had to complete a drug and alcohol treatment program, get a job, make visits once a week. But with the treatment program she was in, she couldn’t leave for extended periods of time to make her visits. She was in violation of her case plan because of her treatment program. So there was this conflict between whether the Department of Human Services was considering what it means for this woman and people like her who are in these kinds of programs that have a lot of stipulations and limitations, because you’re supposed to be focusing on your recovery.

So, here’s a woman who — in less than one month — her life was turned upside down because her children were taken away from her. That could accelerate her addiction, and she could lose her house, her car, her job, and then she doesn’t have anything. So, it doesn’t have to be 20 years in prison. You could be in jail for a week and lose your job. A lot of people are living paycheck to paycheck, so there’s really just one step away from their lives falling apart. One step away from no car, one step away from homelessness.

SEP: What have you been seeing in jails and prisons with the recent pandemic? Some outlets have covered the lack of response in these facilities, and the kind of crisis that could create.

Harvey: I saw that in a jail where there were more than 600 cases, they were literally writing on their windows “help us,” like, “we matter too,” crying out to the public that even if they are in there and convicted of a crime, they don’t deserve to die there because the proper precautions haven’t been taken to make sure they’re not at a greater risk to contract this virus. And we’ve seen people contracting and dying from this virus in federal prisons. There was a man who had served 44 years and he was due out this year, and he just died from COVID-19 behind bars. All of the people who work in these facilities do come back to their communities. So if you don’t think that incarcerated persons are important or valuable or that their health should be considered, think about the people who work in these facilities. This is a public health threat. Some local governments are suspending jail times for low-level violations, or reducing arrests for minor offenses. Some places are releasing pre-trial detainees. We are seeing some things happening, but it’s not happening quick enough.

Featured image: Photo by Rayon Richards.

How Social Distancing Can Help Us Rethink Our Gatherings

Gatherings around the world are cancelled or postponed: Concerts, conferences, religious services, birthday parties, yoga classes, the Olympics, funerals. Almost all instances of people in proximity to one another have suddenly evaporated in the U.S. as many of us have been isolating in our homes.

While the COVID-19 pandemic has altered daily life for most everyone, Priya Parker thinks it has created an opportunity for us to reexamine the ways we connect with one another.

Parker is a trained conflict resolution facilitator who started using a process called “sustained dialogue” at University of Virginia to facilitate meaningful conversations and connections across racial and ethnic barriers. As a biracial woman, she noticed a lack of understanding around race on campus, and she decided to do something about it.

In 2018, Parker published The Art of Gathering, a book that calls on us to reconsider the gatherings we plan and attend, from celebrations to meetings to mass events to dinner parties. Parker’s book offers a new way of determining how we should shape these gatherings into meaningful experiences instead of routine events. She writes that “We spend our lives gathering … and we spend much of that time in uninspiring, underwhelming moments that fail to capture us, change us in any way, or connect us to one another.” Parker believes that we can change this, though, even — and maybe especially — in a time of global crisis.

Her new podcast, Together Apart, produced with The New York Times, tells the stories of people navigating our new reality in their own attempts to gather safely and .

In our interview with her, Parker shared her philosophy of getting people together, socially distanced or otherwise.

SEP: You talk in your book about our “ritualized gatherings” and how they’ve been repeated so much over time that we’re attached to the forms of our gatherings even after they no longer reflect our values. What are we doing wrong when we gather?

Priya Parker: We skip over asking what the purpose is. So, we skip too quickly to form. If we’re hosting a baby shower, we assume it has to look a certain way and skip to buying or making the baby games. I wrote about the New York Times “Page One Meeting” in the book, which continued for more than 70 years even after it no longer made sense to have the biggest meeting of the day focusing on what goes on page one, since they now had this thing called the home page. Whether it’s a baby shower or an editor’s meeting, the biggest mistake that we make when we gather is to assume that the purpose is obvious.

SEP: To zero in on the purpose of gatherings, you suggest finding a “disputable purpose” and even excluding people if necessary, in the right way. A lot of us are rule-averse and want to at least appear laid back when we’re planning gatherings, so how do you think we can start to embrace rules like this?

Parker: I would differentiate between principles and rules. I think something like “know why you’re gathering” isn’t a rule; it’s a principle. It’s not controlling or uptight to be asking “why are we doing this?” It’s intentional.

But I do, in the book, write about pop-up rules. Something like practicing generous authority. Something we tend to do in our gatherings is “underhost.” In wanting to not seem too controlling or bossy, we kind of do nothing. This is an argument to say that if you’re interested in creating transformative, memorable gatherings, the way to do that is to have a specific purpose and to create a sequence or structure — that can actually be delightful and fun.

If the purpose of a baby shower is to help a couple figure out how they want to parent when they’ve never seen a model for that in either of their families before, having a baby shower with all women and pinning the diaper on the baby is not going to help you fulfill that purpose. Gathering is a form of power and it’s also the way we spend our time. I’m not so much an advocate of rules so much as I am an advocate of not wasting people’s time.

SEP: Let’s say you’re at a terrible gathering. You know it’s terrible, and everyone else does too, but you’re not the host. Is there anything you can do as a non-host to make a gathering better?

Parker: I called this book The Art of Gathering and not The Art of Hosting, in part, because I think guests have a lot of power. I know of this retirement party that happened pre-COVID, and the team of a department was invited to a retirement lunch, and everybody came and sat down and they were chatting. The person who sent out the invitations was planning to bring out a cake and a plaque at the end, but there were like two hours before that, so everyone was just kind of waiting around while nothing happened and it was a little embarrassing for the person being honored. Then, one of the guests stood up and clinked their glass and started a round of toasts and stories. It was a risk, right? But people went along with it. It gave structure, and completely transformed the event. Through their intervention, that guest transformed something that was mundane into something that was meaningful.

Sometimes it isn’t obvious who the host is, like if you’re at a conference or something and you’ve spontaneously come together with whoever you’ve bumped into. You can intervene and say, “I’m here because I’m new to the industry. Would you guys be up for a conversation?” and go around answering an interesting question. You have a lot of power as a guest to shape an outcome. Part of it is saying “there is a beautiful conversation that could happen here. How do we have it?”

SEP: I think it’s a little more common these days to come across the idea of introvertedness or social anxiety, and some people say they don’t like to be in gatherings or that they don’t like to be around strangers. But you say in your book that “everyone has the ability to gather well.” Does that run counter to the idea of introvertedness?

Parker: One of the things I found interesting writing this was that I interviewed over 100 people for this book who people described as transformative gatherers — in all different fields, a rabbi, a choir conductor, a hockey coach, a photographer — and many of them identified as introverts or sufferers of social anxiety. One of the things I found, at least anecdotally, is that often introverts — people who don’t like to go to gatherings — are some of the best gatherers. This is because they’re creating the gatherings they wish existed.

When you’re designing experiences for other people, I think it’s almost dangerous to rely on a very charismatic personality to lift the group and carry it through something. When you create thoughtful structure, you don’t actually have to do very much once people arrive. I actually think that often when people don’t like going to gatherings, they’re on to something. They don’t like them when they’re really awkward and they aren’t guided with care. They don’t like gatherings where you have to keep introducing yourself or try to prove your worth. It’s exhausting. But there is another way to do this, and, in my experience, introverts and others who are on the outside of communities are really amazing, thoughtful gatherers.

SEP: When it comes to family and friends with really polarizing politics (I think everyone thinks about this around Thanksgiving for some reason), a lot of strategies go around for gathering people like this and keeping conflict at bay. How would you approach gathering people where politics differ and maybe even values differ as well?

Parker: I think first, again, is know the purpose. Is the purpose to engage in politics? Or to have a good time? If you’re trying to interstitch a community and they’re divided on politics, as a conflict resolution facilitator, one of the things you know is that there are different tools for different conflicts. It may make sense to avoid conversation as a centerpiece of your gathering. It may make sense to do it in a sports league or volunteer together. There are a lot of ways to build relationships, and things that allow people to see different sides of each other are going to help to build that community.

When you’re bringing together people who are different, don’t try to make them the same; try to complicate each side. Krista Tippett said “We assume a monolith of the other that we know not to be true of our own side.” So we think “all evangelical Christians … ” or “all white women …” or “all Muslims … ” whereas we know that there’s so much difference even within our own families.

If you’re going to go for it, my suggestion is to ground a conversation around stories, not opinions. Or, don’t focus on conversation and find a meaningful activity that allows people to show different sides of themselves. People could think, oh wow, he is just as competitive as I am, or, she’s also superstitious. We all have different sides to ourselves, so part of loosening that knot isn’t to focus on stamping out the differences but to bring out the complications of each side because they have something in common.

SEP: I find it ironic that you’re book about gathering has just come out in paperback while we’re all social distancing.

Parker: It is an ironic time to deeply understand gatherings when the world is ungathering.

SEP: But you do have this podcast called Together Apart, so I want to know some innovative or inspirational ways you’ve seen people connecting during this pandemic.

Parker: People are finding really beautiful ways to gather even with social distancing. In this week’s episode, which was on birthdays, an aunt and her nephew organized a birthday party in a parking lot for all of the neighbors and asked them to park their cars in a circle and blare pop music and honk as the birthday boy was going to drive through. It was totally amazing to have a release of joy when people are cooped up in their houses, but in a safe way. One interesting thing I’ve been getting a lot of notes on is people living in neighborhoods all over the country who don’t know their neighbors, and all of the sudden, Facebook neighbor groups are popping up saying, “drinks on the lawn, 12 feet apart, 5 p.m.”

One powerful thing we’ve been seeing online is people whose gathering is unique to this time and wouldn’t make much sense in other times. D-Nice, this D.J. in Miami, started spinning sets three weeks ago, and some of his dance parties are 100,000 people. Michelle Obama stopped by, Bernie Sanders, Mark Zuckerberg stopped by, but it was literally open to everybody. It was a strange combination, that I think is difficult in in-person gatherings, of elite and deeply democratic while allowing these psychological V.I.P.s through the door. It reminded me of a quote from Studio 54 when Andy Warhol was criticized for the red rope, and he said “It’s a dictatorship at the door so that it can be a democracy on the dancefloor.” I think D-Nice is this fascinating example of being a democracy at the door and a democracy on the dancefloor.

There are virtual choirs, collective spin classes and knitting classes, Alcoholics Anonymous, happy hours, and everything in between. And I think families are trying to figure out how we can be together apart in a way that’s safe but still specifically marks a moment in our lives.

SEP: Do you think this is a good time to reconnect with old friends?

Parker: Absolutely. This is a massive, generational, global interruption, and it’s a painful one. It makes us pause and think, who do I love? What have I not been doing when I was overbusy? Beyond the question of reconnecting with old friends, it’s really a good time to reconnect with how you want to live. Part of that is who you want to be part of that life.

SEP: What do you hope people take away from your book?

Parker: My deepest hope is that people pause, at work or home or in the public square, and think more intentionally about how we do things together, and then have the courage and the permission to go invent that new way of being.

Featured image: Shutterstock

10 Literary Classics Turn 50

As hard as it might be to believe, 1970 was 50 years ago. It was the decade of Watergate, the end of America’s involvement in Vietnam, the expansion of the women’s movement, and the rise of the gay rights movement. Environmental concerns moved to the forefront. The era of cable expansion would begin in television, and music would welcome genres like hip-hop, punk, and disco. In literature, 1970 would see the release of a number of print classics. Here are 10 beloved novels that made their debut 50 years ago.

1. Deliverance – James Dickey

Regularly placing on lists of the great books of the 20th century, Deliverance is a harrowing novel of a canoe trip gone horribly wrong. Adapted into John Boorman’s equally disturbing 1972 film, the book charts the journey of four city men who find themselves in the midst of unforeseen danger and moral crises in the Georgia wilderness. It’s the rare book that is praised for both its beauty and its unflinching brutality.

2. Love Story – Erich Segal

At 41 weeks on the The New York Times best seller list, Love Story was far and away one of the most popular books released in 1970. Though tragedy is telegraphed from the opening line of the book, the titular romance between a rich boy and a poor girl captivated readers. Made into a Oscar-nominated movie before the year was out, Love Story remains a pop culture constant.

3. Islands in the Stream – Ernest Hemingway

Though not regarded quite as highly as some of his earlier work, Islands in the Stream earned enormous recognition as the author’s first posthumous release. It was one of a remarkable 332 works that his fourth wife and widow Mary Hemingway found after his death. Written in three sections, the book deals with the life of a painter named Thomas Hudson, with each segment examining a key series of events across Hudson’s life.

4. This Perfect Day – Ira Levin

In his nonfiction examination of the horror genre, Danse Macabre, Stephen King likened Ira Levin to the Swiss watchmaker of suspense, noting that his novels are such perfect constructions of plot and intent that you can’t remove a single piece without damaging their effect. Levin is of course widely known for Rosemary’s Baby, The Boys from Brazil, and The Stepford Wives, but This Perfect Day is also classic Levin. While his most well-known novels take place in a recognizable modern America with a crucial twist here and there, This Perfect Day is fully embraced science fiction, a dystopian work in the vein of 1984 or Brave New World. The book suggests a world run by a single computer with a populace that’s continually drugged to stay happy; of course, the carefully regimented world hides a secret about what’s actually in control.

5. The Bluest Eye – Toni Morrison

Eventual Pulitzer and Nobel Prize winner Morrison was already a groundbreaker before her own work was published. Working for Random House in the ’60s, she was the first black woman to be a senior editor in the fiction department. Her debut novel, The Bluest Eye, firmly established the painfully honest way in which she would tackle racism throughout her literary career. Today, the book is widely included in reading lists for college literature classes and high school AP programs, though its inclusion has frequently been challenged by peopledisapproving of its explicit content.

6 Ringworld – Larry Niven

Larry Niven has been one of the leading voices in science fiction for decades, and one of his most famous and significant works appeared in 1970. Ringworld is a crucial and significant part of his Known Space continuity, generating nearly a dozen sequels and prequels itself. The action of Ringworld centers around a crew journeying to investigate a huge ringed construct that’s supporting life. The character Speaker-to-Animals is a Kzin, a member of the cat-like Kzinti race that Niven first introduced in his short stories and that have appeared in a number of his works; they also exist in the Star Trek universe, first appearing in Star Trek: The Animated Series when it adapted one of Niven’s stories. The Ring structure was an important influence on the Halo gaming franchise. Ringworld won the science-fiction “triple crown” of the Hugo, Nebula, and Locus Awards.

7. The Crystal Cave – Mary Stewart

One of the most important modern retellings of the Arthur legend, Mary Stewart’s The Crystal Cave focuses on the youth of Merlin. Stewart would eventually write four more books in the cycle, using Merlin as the point-of-view character for Arthur’s reign. The Crystal Cave itself was a bestseller and an important element in the wave of fantasy novels that would gain popularity through the decade. Her positioning of Merlin as a POV character and instigator of events has filtered into popular culture, with films like Excalibur using similar tones of characterization.

8. The Naked Face – Sidney Sheldon

Sidney Sheldon’s resume is loaded with classics. He won an Oscar for his screenplay of The Bachelor and the Bobby-Soxer in 1947 and a Tony for the musical Redhead in 1959. Sheldon produced and wrote The Patty Duke Show and created and wrote I Dream of Jeannie. With stage and both large and small screens firmly in his grasp, Sheldon published his first novel in 1970. He promptly received a Best First Novel nomination by the Mystery Writers of America. The page-turner about a psychoanalyst who becomes a suspect in a string of murders was adapted for film three times in three different countries: the U.S., Ukraine, and India.

9. Nine Princes in Amber – Roger Zelazny

Roger Zelazny was firmly established as a top-notch writer of fantasy and science fiction with two Hugos and two Nebulas to his credit by the time that he put out Nine Princes in Amber, the first book in his Chronicles of Amber series. The tale of a battling family struggling across multiple realities grew into a series of 10 novels published over the course of 21 years. Zelazny is considered one of the leaders of the New Wave of science fiction and fantasy; write Neil Gaiman, creator of The Sandman and Good Omens, among others, considers Zelazny a huge influence on his work.

10. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West – Dee Brown

Dee Brown grew up with a love of history and a particular interest in the American West. He became a writer and a librarian, serving in the librarian capacity for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the U.S. Department of War during World War II, and as the agriculture librarian for the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Throughout his career, Brown wrote constantly, publishing both novels and nonfiction. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee was his eleventh history book, but it’s easily his most famous. It deals honestly with how the United States government treated native tribes during Westward Expansion, casting a harsh light on the government’s frequent efforts to eradicate the people and their culture.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Cartoons: Author! Author!

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

January 24, 1953

Roland Coe

November 29, 1952

Locke

September 13, 1952

Doris Matthews

April 28, 1951

Goldstein

February 7, 1953

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Top Ten New Reads for Spring

Fiction

Apeirogon

Apeirogon

by Colum McCann

Two fathers, one Palestinian and one Israeli, have both lost their daughters to violence. Their lives intertwine as they attempt to use their grief as a weapon for peace.

(Random House)

The Mirror & the Light

The Mirror & the Light

by Hilary Mantel

This third installment of the much-ballyhooed Wolf Hall trilogy details the downfall and grisly end of Thomas Cromwell, Henry VIII’s infamous chief minister.

(Henry Holt)

Saint X

Saint X

by Alexis Schaitkint

Years after her sister was murdered on a family vacation to the Caribbean, Claire forges a bond with a resort employee who was arrested for the crime but released for lack of evidence.

(Celadon Books)

Writers & Lovers

Writers & Lovers

by Lily King

Casey Peabody, a struggling writer who has been utterly undone by the death of her mother, must pilot through some of life’s most profound, confusing, and difficult transitions.

(Grove Press)

The Two Lives of Lydia Bird

The Two Lives of Lydia Bird

by Josie Silver

Just as Lydia forces herself to start dating again after losing her partner of 10 years, she begins living parallel lives, one in the present and one where Freddy is still alive.

(Ballantine)

Nonfiction

The Splendid and the Vile

The Splendid and the Vile

by Erik Larson

Drawing on memoirs, diaries, letters, and recently declassified material, this is a front-row seat to Winston Churchill’s first year as prime minister, when the Germans were closing in on London.

(Crown)

Rust

Rust

by Eliese Colette Goldbach

The author returns to her hometown of Cleveland and takes a job at the steel mill because the paycheck offers a way out of poverty. But, well-educated and bipolar, she’s not your typical steel worker.

(Flatiron Books)

Untamed

Untamed

by Glennon Doyle

In her most personal book yet, the activist and bestselling author shares her story of falling in love, divorcing her husband, marrying her wife, and realizing that the most important voice to listen to is your own.

(The Dial Press)

The Velvet Rope Economy

The Velvet Rope Economy

by Nelson D. Schwartz

A gripping look at how a virtual velvet rope divides Americans in everyday life — from airport security lines to theme parks — creating a friction-free life for the moneyed and a Darwinian struggle for the middle class.

(Doubleday)

Chanel’s Riviera

Chanel’s Riviera

by Anne de Courcy

The Cote d’Azur in 1938 was awash in glamour, with Coco Chanel at its center. But as Nazis swooped in, it was transformed by war, and the city under siege wrought powerful stories of tragedy, sacrifice, and heroism.

(St. Martin’s Press)

This article is featured in the March/April 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock.com

Top Books for Holiday Gift Giving

Fiction

The Starless Sea

The Starless Sea

by Erin Morgenstern

In The Night Circus author’s new novel, a student in Vermont uncovers a book filled with tales of lovelorn prisoners, key collectors, nameless acolytes, and astonishingly, a story from his own childhood.

(Doubleday)

Blue Moon

Blue Moon

by Lee Child

Jack Reacher comes to the aid of an elderly couple under threat from rival gangs, delivering the justice that comes along only once in a blue moon. Early readers are saying this is one of Child’s best.

(Delacorte)

The Confession Club

The Confession Club

by Elizabeth Berg

In this heartwarming, inspiring novel, a monthly dinner party in Mason, Missouri — sparked by a surprising revelation — is renamed the Confession Club, where friends are free to share their secrets.

(Random House)

The Innocents

The Innocents

by Michael Crummey

Orphaned siblings are left to live in an isolated cove on Newfoundland’s northern coast. With little knowledge of the world, they must survive on their wits and any lessons they can recall from their parents.

(Doubleday)

The Revisioners

The Revisioners

by Margaret Wilkerson Sexton

This National Book Award-nominated author’s newest novel explores race, legacy, trust, and hope in the South in chapters that alternate between the 1920s and the present.

(Counterpoint)

Nonfiction

The Man Who Solved the Market

The Man Who Solved the Market

by Gregory Zuckerman

The true story of Jim Simons, a former code breaker who mastered the stock market, averaging annual returns of 66 percent and building his personal worth to $23 billion.

(Portfolio)

The Winter Army

The Winter Army

by Maurice Isserman

The epic story of the U.S. Army’s 10th Mountain Division, who broke Germany’s last line of defense in Italy’s mountains in 1945, spearheading the Allied advance to the Alps.

(Houghton Mifflin Harcourt)

The Great Pretender

The Great Pretender

by Susannah Calahan

The Brain on Fire author investigates a 50-year-old mystery behind a dramatic Stanford experiment that changed the way we view mental health.

(Grand Central Publishing)

Notre-Dame

Notre-Dame

by Ken Follett

The bestselling author reflects on the great cathedral — its history, its influence, and the emotions that gripped him when he learned about the fire that threatened to destroy it.

(Viking)

That Wild Country

That Wild Country

by Mark Kenyon

Part travelogue, part history, That Wild Country takes readers on an intimate tour of our wild public places, examining how they came to be and what the future might hold for them.

(Little A)

This article is featured in the November/December 2019 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock.com

Reckoning with the #MeToo Movement: An Interview with Linda Hirshman

There was a whisper in one of my online communities. “My former manager is on the job market,” one tech woman wrote. “Since he’s leaving the company due to being put on a PIP (personal improvement plan) for his treatment of women and PoC employees, I thought I’d warn people. Here’s his name.”

For most women, the #MeToo movement wasn’t a surprise — except perhaps that so many famous men finally faced the consequences of their actions. Given the dismal gender ratio in many professional fields, and recent reports about abuses in every business from Hollywood to tech firms, preventing sexual harassment is an urgent matter to women. I’ve met few women without a personal story about sexual harassment or sexism.

We have seen several reasons to cheer at the #MeToo movement, as well as heartbreak when we see how little progress has been made. At best, we’re in a time of transition, where previously-accepted behavior now results in someone losing his job.

As is true during any time of change, it’s important to understand where we started, how we got here, and how the past should inform our path forward.

That’s why I so urgently wanted to sit down with Linda Hirshman. Her book, Reckoning: The Epic Battle Against Sexual Abuse and Harassment, lays out the important events in the pursuit of justice for workplace harassment, explains its unresolved legal issues, and compares it to earlier social changes. It’s not just that Hirshman is an experienced lawyer who has argued in front of the Supreme Court, or that she’s a marvelous writer (the sort who makes you stay up past your bedtime to read “just one more chapter”). I wanted Hirshman’s wisdom personally because I learned so much from her earlier book, Victory: The Triumphant Gay Revolution, which chronicles the social history of the LGBTQ movement.

(For transparency: I know Hirshman, though not exceptionally well. She’s a member of my book club, and, it turns out, the exact right person to explain Oscar Wilde’s legal problems in the context of The Picture of Dorian Gray.)

I wanted to find out how the #MeToo movement compared to similar movements to advance human rights; what moved it from the theoretical to the practical? How far away are we from genuine societal change?

As Hirshman writes in Reckoning, “In any social justice movement in America — abolition, racial civil rights, feminism, gay rights — the battle always seems to involve the same three campaigns, although not always in the same order. First, the movement must appeal to the judiciary and the rule of law, so central to American Democracy. Yet the court does ultimately follow the election returns, so the second field of battle is popular politics. Finally, to achieve the first two goals of legal and political change, a movement must, at day’s end, win the air war and change the culture.”

The nature of the cultural part of social change depends on the time and place. “The piece that interested me is the media,” Hirshman says. In the gay revolution, the theater was a key influence. In #MeToo, it’s been the Internet and print media. (You can read a book excerpt from Hishman’s Reckoning, about the feminist Internet, The Revolution will be posted.)

One frequent element of real social change is a backlash, Hirshman explains, once you get close to the tipping point. “You get this weird social change,” she says, as the established culture responds with a pendulum swing to the old ways of doing things. She has a whole chapter about how the establishment culture responded to feminism, and what it took for it to revive.

These events look like a setback, Hirshman says. “But under the surface, social change is accepted. You get a little more of what you need.” The backlash has unpredictable consequences, such as the Clarence Thomas hearings (where Anita Hill’s testimony of sexual harassment was rejected) that led to more women going into office, in what became known as the “Year of the Woman.”

Some men become paranoid in the wake of the movement, scared to interact with women lest they be accused of impropriety. For example, 60% of male managers now say they’re uncomfortable mentoring women. Doesn’t that get in the way of women moving forward?

Hogwash, Hirshman says. Men were already refusing to mentor women, or to fund women in venture capital.

“This is male hysteria,” she says. “It’s punitive. There is no universe in which going to coffee with someone will be mistaken for romantic behavior. Men threatening to stop [meeting with women professionally] are blackmailing uppity women. To say nothing of being illegal according to the civil rights act of 1964.”

There’s nothing wrong with a professional relationship, she points out. But don’t try to date someone when you are in a business relationship, where you can possibly have a career impact on the other person.

“The social power is so heavily in favor of the men that they just shouldn’t [look for a romance at work]. If that means less courtship, so be it.”

Hirshman would like us to keep in mind that social change always happens when there is a crack in the establishment. “The arc of history does not bend towards justice; it more wiggles like a politician who discovers his cell phone has been hacked,” Hirshman says.