Review: Rebuilding Paradise — Movies for the Rest of Us with Bill Newcott

Rebuilding Paradise

⭐ ⭐ ⭐ ⭐

Rating: PG-13

Run Time: 1 hour 35 minutes

Director: Ron Howard

In Theaters July 31, Streaming Soon

An explosion of horrific immediacy launches Ron Howard’s documentary about the aftermath of the 2018 Camp Fire, a wildfire that consumed the town of Paradise, California. Making ingenious use of terrifying phone video footage and anguished audio recordings, Howard recreates the chaotic hours when some 24,000 residents went from dropping their kids at school and getting ready for work to racing for their lives through the very gates of a fiery, smoke-choked hell.

“Are we going to die?” a motorist asks a cop who has just informed her all routes of escape are engulfed. “My house is burning,” a patrolling cop reports as dash-cam footage reveals a ball of fire erupting under a cloud of smoke. “Please, God, help us! The windows are melting!” an unseen driver screams as she rolls uncertainly by the shells of burned-out cars.

And finally, after what seems like an eternity, an escaping family’s camera catches a glimpse of blue sky beyond the cloud of smoke.

“We’re going to make it!” the dad yells triumphantly. From the back seat comes the sound of a little boy crying hysterically.

It’s as powerful a 15 minutes as you’ll ever see open a film; Howard’s domestic answer to Steven Spielberg’s D-Day sequence in Saving Private Ryan — only in this case the cinematographers are ordinary people who had the presence of mind to record for posterity what could have been their final minutes.

Howard’s actual camera crew doesn’t arrive in Paradise until a week or so after the flames have burned themselves out, while the town’s displaced residents are still finding places to stay — sitting shell-shocked on cots in a gymnasium, settling in the basements of distant relatives, camping in tent cities on football fields. Their eyes are empty, their mouths slightly agape in did-this-really-happen disbelief.

But the director isn’t interested in telling a story of hopeless tragedy. With a faith in human resilience that has marked his films from A Beautiful Mind to Apollo 13, Howard seems assured of Paradise’s resurrection even before its resident are. Focusing on a handful of indelible characters, he chronicles their slow realization that even after everything changes, life goes on.

One of them is Steve “Woody” Culleton, himself a story in resurrection, the self-described “former town drunk” who dried out, turned his life around and eventually became mayor. Beloved by his fellow Paradisians, he’s among the first to declare he’ll never leave the town, and even before the ashes have cooled has already drawn up plans to rebuild his home.

We patrol the streets of Paradise — indeed, to a large degree only the streets remain — with local cop Matt Gates, an incredibly cool guy who should be played in the narrative version of this film by Deadpool’s Ryan Reynolds. It is he who witnessed his home collapse in flames while on patrol, but he wonders aloud, “I don’t know if it’s worse to have lost your house or be one of the few whose homes came through it.” In one of the film’s few lighter moments, he gestures to an empty lot he’s passing. “It’s cliché, I know,” he says. “But that used to be the donut shop.”

Another is Superintendent of Schools Michelle John, who despite the fact that some of the town’s school buildings are now smoking rubble, determines Paradise will retain its educational identity, setting up makeshift classrooms in houses, barns, and shopping malls. We meet her devoted husband Phil, who surrenders hereto the endless hours of duty while gently reminding her to eat and sleep. “You’re no good to anyone if you’re sick,” he cautions her as they sit in the living room of a distant cousin who has taken them in. As if to prove to the scorched landscape that Paradise will not be bowed, John vows to hold the high school graduation on the football field — intact after the fire but surrounded by towering dead trees that first need to be brought down (and which FEMA, helpful but a tangle of red tape, resists accomplishing on time).

The story of Paradise’s rebuilding is not a litany of improbable success stories. Many people leave town forever, unable to face the memories of that awful morning. At the moment of her greatest triumph — the football field graduation she dreamed of — John is struck with unspeakable personal tragedy. And even good-natured Officer Gates discovers the personal price a community-wide calamity can inflict when you’re not looking.

But this is a Ron Howard film, and in Paradise he has found the real-life crystallization of what he has proclaimed throughout a life on film: In the end, the human spirit will always rise, quite literally, from the ashes.

Featured image: A home burns as the Camp Fire rages through Paradise, CA on Thursday, Nov. 8, 2018 (Photo by Noah Berger) (provided by Bill Newcott)

Considering History: Baseball, Chinese Americans, and the Worst and Best of America

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

In honor of Asian and Pacific Islander American Heritage Month, PBS is airing this week a compelling and vital new five-part documentary, Asian Americans. This examination of the longstanding, multi-faceted histories of the Asian-American community (across many different nationalities and cultures) could not come at a more important moment, as xenophobic and racist associations of COVID-19 with China have led to a dramatic spike in harassment and hate crimes targeting Asian Americans.

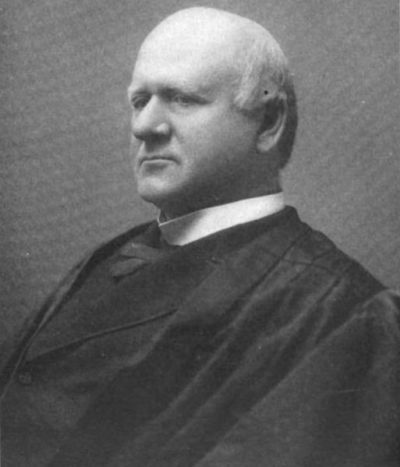

Such prejudice and violence are driven by equally longstanding collective narratives of Asian Americans not only as carriers of disease, but also as fundamentally outside of and foreign to “American” identity. Even a prominently progressive American figure like Supreme Court Justice John Marshall Harlan wrote, as part of his famous dissent to the Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) decision, that Chinese Americans were “a race so different from our own that we do not permit those belonging to it to become citizens of the United States” (contrasting that idea with his support for African-American equality under the law). In a public lecture two years later, he went even further, arguing that “this is a race utterly foreign to us and never will assimilate with us.”

In that late 19th century era of Chinese-American exclusion, such racist and xenophobic sentiments were given voice not only in governmental and legal documents, but also in violent gatherings of white supremacist protesters and agitators. Yet in one of the most prominent sites for these angry and divisive gatherings, a sandlot in California, we can also find a far more inclusive and inspiring vision.

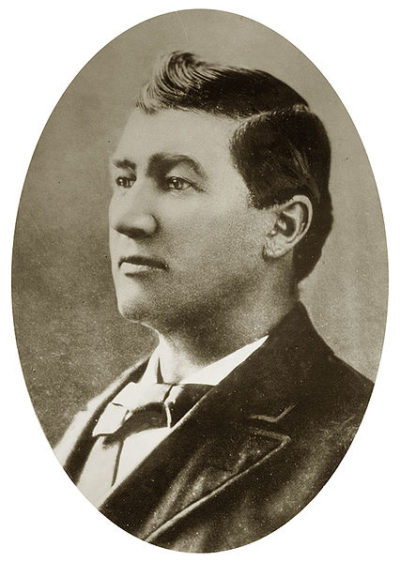

As anti-Chinese sentiment became a dominant social and political perspective in the 1870s, one of its leading proponents was an Irish-American businessman, labor activist, and demagogue named Denis Kearney (1847-1907). Born in County Cork, Ireland, Kearney left home at the age of 11 and sailed the globe for a decade on clipper ships, working his way up from cabin boy to first mate before finally settling in the U.S. in 1868. Over the next decade, he married a fellow Irish immigrant (Mary Ann Leary), started a family, and established a successful delivery business in San Francisco, but it was his evolving labor and anti-immigration activism that would earn him national attention.

Kearney’s activism began with a focus on labor, including specific opposition to a city monopoly on hauling and broader support for workers’ rights; to that end he helped found in 1877 a new political party, the Workingmen’s Party of California. But he became especially famous for his fiery rhetoric, often delivered at an outdoor San Francisco space known as “The Sandlot.” In speeches that often lasted as long as two hours, delivered to thousands of angry workingmen, Kearney attacked opposition politicians, advocated for violence if their demands were not met, and, more and more over time, identified Chinese Americans as the community’s true adversary (leading the era’s anti-Chinese narratives to be frequently called “Kearneyism” and “Sandlotism”).

Kearney’s oratory quickly gained national prominence, and a February 1878 Sandlot speech reprinted in the Indianapolis Times exemplifies his incendiary, violent, and anti-Chinese rhetoric. “Do not believe those who call us savages, rioters, incendiaries, and outlaws. We seek our ends calmly, rationally, at the ballot box,” he argues, but he adds, “We shall arm. We shall meet fraud and falsehood with defiance, and force with force, if need be…We are men, and propose to live like men in this free land, without the contamination of slave labor, or die like men, if need be, in asserting the rights of our race, our country, and our families.” And he concludes, “California must be all American or all Chinese. We are resolved that it shall be American, and are prepared to make it so.”

Kearney ended most of his speeches with the repeated phrase “The Chinese Must Go,” which became likewise a campaign slogan for the Workingmen’s Party of California. Profoundly influenced by these social and political developments, over the next decade-and-a-half Congress would pass the Chinese Exclusion Act and follow-up laws like the Scott and Geary Acts, measures designed not just to limit future Chinese immigration but also to destroy the nation’s existing, sizeable Chinese American community. They did not succeed at doing so, but these laws and policies did drastically affect all Chinese Americans, as illustrated by the story of a baseball team and another California sandlot.

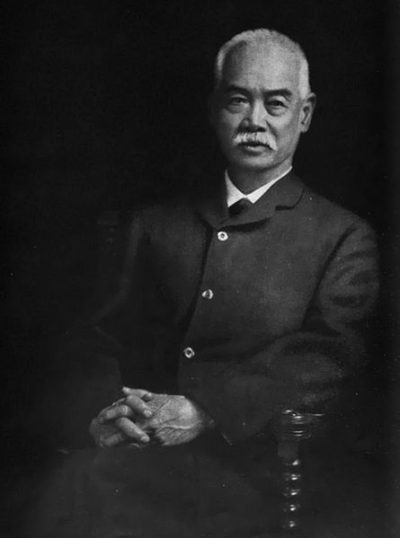

While anti-Chinese sentiment developed across the 1870s, so too did the story of a very different American community, the Hartford (CT) Chinese Educational Mission (CEM). Opened in 1872 by Yung Wing (1828-1912), the Chinese American diplomat, activist, and educator, the CEM brought 120 Chinese young men to the United States to study at New England preparatory schools and colleges, live with American families and communities, and, in Yung’s words from his 1909 autobiography My Life in China and America, “grow in knowledge and stature under New England influence.”

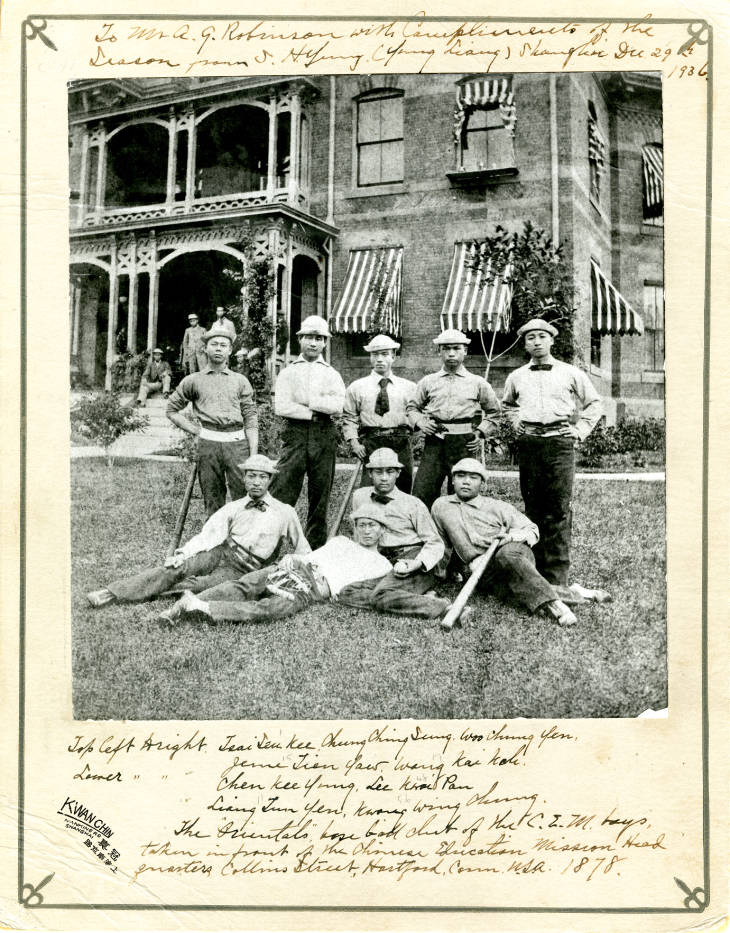

One product of that influence was the Chinese Educational Mission baseball team. Known officially as the Orientals but usually referred to by their preferred name, the Celestials, the team featured CEM students who had been star athletes at Yale (among other college squads). In the mid-1870s the Celestials joined one of the era’s new semi-pro baseball leagues, making quite a name for themselves on that New England regional circuit. In a chapter from his 1939 autobiography, the prominent literary scholar William Lyon Phelps, a high school and Yale classmate of many of the students, describes the team’s strengths and successes at length, noting for example of its star pitcher Wu Yangzeng, that “he was a great pitcher, impossible to hit.”

The period’s rising anti-Chinese sentiment led the U.S. government to break promises to support the Chinese Educational Mission, and in 1881 the school was closed and most of the students forced to leave the U.S. But before they disbanded, the Celestials experienced a final, symbolic moment on a California sandlot. The departing CEM students traveled to San Francisco in the summer of 1881 to take a steamship away from their adopted home and back to China. While they awaited that departure, a local Oakland baseball team challenged the Celestials to a game. It’s unclear whether that challenge represented bad or good sportsmanship, an extension of anti-Chinese sentiment or a brief respite from such divisions and discriminations. In any case, as CEM student Wen Bing Chung would later write, “the Oakland men imagined that they were going to have a walk-over with the Chinese.” But the Celestials rose to this almost unimaginable moment and won their final game by a score of 11–8, per a September 4, 1881, story in the San Francisco Chronicle.

The battle between exclusionary and inclusive definitions of American identity has always been with us, but is never more significant than in times of national emergency and trauma. In such moments, we desperately need to remember the stories captured in the PBS documentary — and embodied by the California sandlots that reflect the worst and best of America, in the late 19th century and in 2020.

Featured image: The baseball players of the Chinese Education Mission, 1878 (Thomas La Fargue Papers, MASC, Washington State University Libraries. Used with permission.)

A Letter from Sacramento, Where Fear Blooms as Flowers Grow

Our front garden hit peak bloom just as the COVID-19 death toll passed 200 in California. As usual, the California golden poppies seized control of the gravel borders along the driveway and, in a brazen move, advanced this spring into the chipped bark meant to provide walking space around the raised planter boxes. Now the last daffodils poke their heads out among the crimson flutter of the Greek poppies. The irises are flaunting wings and beards, each according to its wont, in random pairings around the yard. And the redbud is in full blossom on Mount Robin—the formal name for the mound of native plants my wife has let loose to the south of the front walk.

The garden has staged memorable spring performances before, though always to small audiences. We live four miles south of the State Capitol, well off the beaten path, on an eyebrow street just six houses long, connecting nothing to nowhere. Our hilly neighborhood of ranch houses was built without sidewalks in the early 1950s, when California planners were certain that walking was obsolete.

Weeks ago, back in normal times, only a few familiar souls would wander by. The dog walkers from the next block over. The slight blond teen walking bent, like a peasant woman carrying a bundle of firewood, under a backpack full of textbooks. The mother going to and from the nearby elementary school to retrieve her kids.

I haven’t seen the mother or the teenager since a substitute teacher at the elementary school died of COVID-19 and the schools shut down. But 13 days into the lockdown, as I sit in the garden to read on a sunny afternoon, what was once a trickle of walkers and bicyclists has broadened into a steady stream of people with nowhere else to go.

Many of the faces are new, and they arrive in family groups. The children are frisky and boisterous; the parents who trail them look like they’ve missed their naps. Some couples push baby strollers. Other couples push themselves, striding by fiercely to get the exercise they no longer get at the gym. In a role reversal, there are middle-aged children walking their elderly parents. The daughters tend to walk six feet to the side of the parent, letting them set the pace. The sons tend to lead, getting far out front, then pausing to let the parent shuffle within the prescribed distance before taking off again.

The irony here is that, for me, the social distancing that now fills our street is a social flowering. Coronavirus isn’t my first epidemic. In 1954, I was one of the 38,476 Americans paralyzed by polio.

There are lone walkers, too, talking loudly to their white headphones. One woman gestures with her hands, as if to make the decisive point in what may be a conference call in motion. In a few instances the person ambling up the street is someone we haven’t seen since a school committee meeting or a dinner party sometime in Bill Clinton’s first term.

Often people stop to admire the garden. We talk across the wide bed of Jupiter’s Beard, and I answer the horticultural questions if my wife is busy. The one with the tangerine flowers is mallow, I say, and behind it is the lupine, another native.

The irony here is that, for me, the social distancing that now fills our street is a social flowering. Coronavirus isn’t my first epidemic. In 1954, I was one of the 38,476 Americans paralyzed by polio. Sixty-six years later, in a wheelchair and no longer driving, I don’t get around much anymore. That’s especially true during flu season, when I try to stay away from the contagion. My “weak breathing muscles,” as my brother-in-law, the anesthesiologist, puts it, make me a good candidate to become a statistic again. Before the coronavirus arrived, I was fully trained for the loneliness Olympics, and in these recent early heats I haven’t yet had to break a sweat.

Until three months ago, I thought my 1954 epidemic experience had prepared me for the fear too.

I have only a few memories of those early days: Waking feverishly on the night the poliovirus took hold and then collapsing on the pink tile floor after my father carried me to the bathroom. Lying the next day on a hard table, under bright lights, in a mint-green operating room, to get the spinal tap that would confirm my illness. Being taken to an isolation room where everyone around me was shrouded in gowns and masks; even my parents were allowed no closer than the doorway. I don’t remember being scared. But I don’t doubt that it was fear that etched those memories into my consciousness.

The boy soon put the fear behind him. Today, the man he became isn’t as successful. The fear comes and goes in waves throughout the day. It follows me to bed in the evening, and it greets me in the morning when I open my eyes.

I am not alone in this.

“Did you sleep well?” I ask my wife.

“Yes,” she says, “but I had a dream about the grim reaper coming to the door to sell Girl Scout cookies.”

I do not fear for us. We have been physically distanced from the rest of the world for a month now. The virus is unlikely to breach our garden moat, not even in the guise of a Thin Mint, but I cannot hold out the images and news of the world around us.

I try to keep things in perspective.

You know from your reading, I tell myself soothingly, that folly and cupidity have marked every epidemic. Mom and dad went through the polio epidemics without losing their poise.

You’re right, I reply to myself. But would they have felt the same if people in their time were holding “polio parties”? And my parents probably took some comfort in having a president who was competent enough to organize and execute an invasion to destroy Nazi Germany.

Close the computer, I tell myself. Go to the garden. You’ll find calm and escape there.

Top of Form

So I pick up a book, roll through the front door and down the ramp. It’s warm and the air is thick with the mingled scents of the blossoms. I hear the footsteps of a jogger coming up the street. I look up and see her head emerge above the borage in the planter. She is wearing a mask. It’s the first I’ve seen.

I look over at the Greek poppies. I had it wrong. They aren’t fluttering, they’re trembling. And inside the incandescent red bowls blazing in the sun, there is a shadow.

Originally published at Zocalo Public Square.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Post Travels: Exploring California’s Striking Big Sur

It’s the type of drive road trips are made for. Along California’s central coast, Highway 1 twists and turns its way through Big Sur, awarding those behind the wheel with spectacular views of rugged coastline and sandy beaches. The two-lane road is narrow but as this video shows, leads the way to waterfalls, wildlife, state parks, and unforgettable scenery.

See more Post Travels.

Post Travels: The Beauty of Armstrong Woods

Visitors to the San Francisco Bay Area flock to Muir Woods National Monument by the carload. But for those willing to venture a bit father to the north, Armstrong Woods State Natural Reserve quietly awaits. Located in Sonoma County’s quirky city of Guerneville, there’s no need to reserve parking or book a shuttle. As this video shows, depending on the time of day, you could have the towering grove of redwoods — many growing before the Pilgrims arrived at Plymouth Rock — practically all to yourself.

See more videos at www.SaturdayEveningPost/Video.

Post Travels: Fly Fishing, Ghost Towns, and Hot Creeks at Mammoth Lakes

California has a reputation for its road trip inspiring scenery. Places like Big Sur and Napa Valley are well-known, but scenic rewards await for those willing to venture off the beaten path.

Located in the Sierra Nevada Mountains, impressive snowfall defines its winters, but when warmer temperatures prevail, Mammoth Lakes boasts trails for biking and creeks that make you want to take up fly fishing. Mono Lake is surrounded with limestone towers, and at Bodie State Historic Park you can walk the worn streets of a bona fide gold-mining ghost town. Pictures don’t do it justice, but just might inspire you to get a trip on the calendar.