College of Dreams: Creating a Bright Future for ALL Students

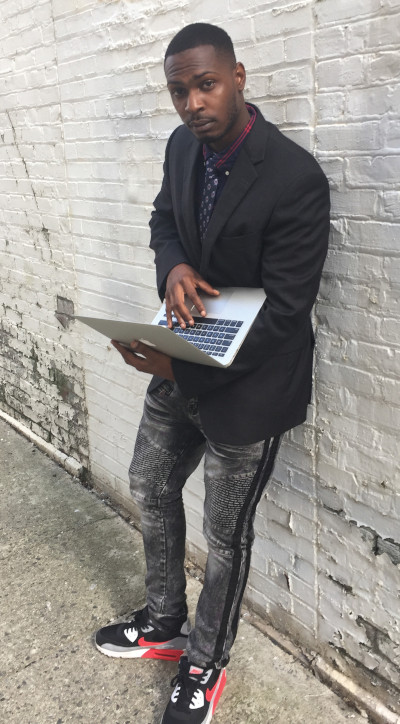

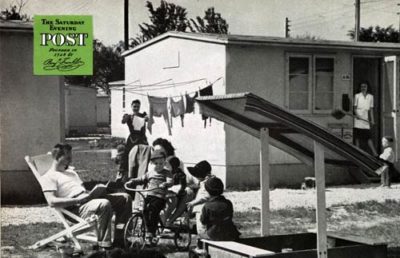

Where Princeton Nelson came from, a college education wasn’t just at the outer edges of possibility, it was beyond imagination. Yet here he was, a proud member of the class of 2018 at Georgia State University, a computer science major with a cap and gown and a more than respectable 3.3 GPA, taking his place at a crowded indoor commencement ceremony along with the Atlanta Fife Band and professors in gowns of many colors and a cascade of balloons in Panther blue and white that tumbled from the ceiling like confetti.

He, too, got to shake hands with the university president, Mark Becker, whose welcoming remarks had invoked “the magical power of thinking big.” He, too, got to hug his fellow graduates, many of them seven or eight years younger than him. He, too, could bask in the pride of his relatives, none more amazed or delighted than the grandmother who had thrown him out as a teenager because he’d been too unruly to handle.

Princeton Nelson came from nothing, and he understood at an early age that it would be up to him to carve a path to something better.

Nelson came from nothing, and he understood at an early age that it would be up to him to carve a path to something better, because nobody else was going to do it for him. Even when he slipped — and he slipped a lot — he knew the choices he made could mean the difference between life and death. He was born in an Iowa prison, the child of two parents convicted of drug dealing at the height of the crack cocaine epidemic.

Mostly, he was raised by his grandmother, Loretta, who did her best to raise Nelson and three siblings on an assembly worker’s salary in a small red house in suburban Chicago. Nelson’s mother was in no state to take him even when she got out of prison. She fell back into the drug underworld and, months after her release, was found shot to death in an abandoned building on Chicago’s South Side.

Loretta moved Princeton and his siblings to Atlanta for a fresh start, but there was little she could do to make up for what he had lost — or never had. By sixth grade, he was attending an institution for children with severe emotional and behavioral problems. His grades yo-yoed, he bounced in and out of special schools, and he barely graduated from high school.

Turning himself around was a long and painful process. For years, he worked in warehouses and smoked weed and gave little thought to where his life was going. Still, he hated the feeling that he was a disappointment to his grandmother. He signed himself up at Atlanta Technical College, thinking at first that he’d train to be a barber. Then it dawned on him that as long as he was taking out loans he’d be better off working toward an academic degree, not just a trade qualification. As it happened, there was a community college, Atlanta Metropolitan, right across the street, and he wandered over one day to enroll as a music major. He’d always enjoyed creating music beats on his grandmother’s computer. Why not see where it could take him?

As he stood in line to register, he noticed a chart listing the professional fields expected to be most in demand in the Atlanta area by 2020, and his eyes fell on the words “computer science.” “What did I have next to me in my grandmother’s house this whole time?” he said. “A computer!” It wasn’t just music beats that he’d created. He’d also worked on MySpace pages and video games, never thinking there could be a future in it. But now, apparently, there was. “It was a flash of light,” he said, “I’m thinking, I’m a computer science major. That’s my calling.”

Nelson’s grades were strong enough to earn him an associate’s degree in computer science in two years. But his life, like that of almost every lower-income college student, remained precarious at best, a constant battle for time and money. When his aunt and uncle bought the house where he and his grandmother were living, one of the first things they did was evict him, saying they were concerned about his pot use and the shortcuts they suspected he was taking to make ends meet. Before he could think of pursuing his studies further, he had to deal with the realities of homelessness. For two weeks he slept on the concrete floor of a bus station so he could bump up his savings from a job flipping burgers and buy himself a car. Once he had his Volkswagen Jetta, he signed on as an Uber driver. Soon he had a third job, as a security guard. Three days a week he stayed in a hotel to enjoy a bed and a hot shower; the other four days he parked overnight at a 24-hour gas station or outside a Kroger’s supermarket where the lights and security cameras made it less likely he’d be robbed, or worse.

He was still homeless when he started at Georgia State in the fall of 2016, but starting in his second year, he joined forces with two of his fellow computer science majors and started designing websites as a side gig. That made him hopeful enough to move out of his car and put all his savings into a deposit for an apartment. It was touch and go at first, because the freelance design work didn’t come in as quickly as hoped, and he had to take a full-time job as a cellphone technician for two weeks to make what he needed for the next month’s rent.

To many eyes, Nelson might not have looked like college material at all. Georgia State, though, was starting to enjoy a national reputation for its pioneering work in retaining and graduating large numbers of students much like him — poor, Black, and struggling to make it as the first in their family to attend college. The university understood his need for extra support. When it became apparent he was depressed because of the financial pressures, he was encouraged to see a campus therapist, the first counselor he’d ever talked to. Twice when his money was running dangerously low, the university awarded him grants to help him reach the finish line.

Academics were never Nelson’s problem. Next to what he’d been through, a challenging course in math or programming held no terrors. Rather, he became fascinated by what it meant to live a normal, middle-class life and was determined to learn how to lead one himself. “I’m always thinking about where I came from. And I still feel like I’m dumb, like I’m still competing with all these college students and falling short.”

While the children of the rich and the very rich continue to enjoy expanding opportunities to pursue a university education, the prospects for everyone else have either stagnated or narrowed dramatically.

It’s a feeling that did not go away even after he graduated and headed toward his first full-time job as a software engineer for Infosys. “That’s the difference between me and those Harvard kids,” he said. “If people like me fail, we’re going to fail our life.”

Nelson was far from the only member of Georgia State’s class of 2018 with a tale of adversity and triumph. Greyson Walldorff, who had been forced to give up an athletic scholarship in his sophomore year because of a concussion, stayed afloat and completed a business degree by starting a landscaping company that grew over time to five employees and more than a hundred clients. Larry Felton Johnson completed a journalism degree on his fourth try, 49 years after he first enrolled, thanks to a state program that offered free tuition to students over the age of 62.

Then there was Savannah Torrance, who had almost dropped out in her freshman year because she was commuting 60 miles each way from her mother’s house, working long shifts at a supermarket, and absolutely hating the chemistry class she thought she needed to build a career in the medical field. Thanks to some timely guidance from Georgia State’s advising center, though, she switched to speech communications, which required no chemistry, won a state merit scholarship she’d narrowly missed out of high school, and was soon thriving both in her studies and as a student orientation leader, university ambassador, and member of the student government association.

Georgia State boasts almost no success story that doesn’t include at least one moment where everything was in danger of crumbling to dust. At a school where close to 60 percent of undergraduates are poor enough to qualify for the federal Pell grant, that is just the nature of things. What is remarkable about Georgia State students is that despite the precariousness of many of their lives, they still graduate in extraordinary numbers. In 2018, more than 7,000 crossed the commencement stage, 5,000 of them to pick up a bachelor’s degree and the rest an associate’s degree from one of the university’s five community college campuses scattered around the Atlanta suburbs. That translated to a six-year graduation rate of close to 60 percent, significantly above the national average.

Georgia State’s achieved a 74 percent increase in the graduation rate over 15 years. This is not just about the lives of a few unusually tenacious and talented individuals. We are talking about a fundamental transformation, a real-time experiment in social mobility that the university has learned to perform consistently, and at scale.

How did Georgia State do it? In the wake of the 2008 recession, a new leadership team at Georgia State, acting out of economic necessity as well as moral conviction, determined that there was nothing inevitable about the failure of students who were poor, or nonwhite, or whose parents had never attended college. Rather, what held them back were barriers erected by the university itself and by the broader academic culture. Georgia State developed data to understand those barriers and to identify the inflection points where students most commonly came to a crossroads between success and failure. For years, Georgia State has graduated more African Americans than any other university in the country — not by tailoring special programs to them but by treating them like everyone else and providing support where they need it, regardless of wealth, or skin color, or any other consideration.

While the children of the rich and the very rich continue to enjoy expanding opportunities to pursue a university education, the prospects for everyone else have either stagnated or narrowed dramatically.

Once, student success was thought to be a simple combination of academic promise and hard work. Now even the pretense of that egalitarianism is gone; it’s all about money and whether your parents went to college. A study by the National Center for Education Statistics from 2000 — when things were better than they have become — found that a student in the top income quartile with at least one college-educated parent had a 68 percent chance of graduating before the age of 26, whereas a student in the bottom quartile whose parents did not go to college had a 9 percent chance.

It’s not that these staggering problems have gone unnoticed. Mostly, institutions have been at a loss to address them. Many prefer to keep their focus elsewhere — on graduate programs, on research, or on cultivating an elite class of undergraduates from that golden upper quartile. Some like to point fingers: at the shortcomings of the K–12 education system, at budget-cutting state legislatures, at a political culture that loves to hate academia and questions why students don’t invest in their own futures instead of relying on the public purse for financial aid. It has become fashionable for elite institutions to brag about the lower-income students they champion and finance, but they do this at a scale entirely dwarfed by a public university like Georgia State, which has three times as many Pell-eligible students as the entire Ivy League.

It has taken more than 20 years to come up with a more durable answer to the problem and to push back against a higher education culture that too often serves the interests of everyone but the students. The first stirrings came at a handful of public universities in Florida, Georgia, Tennessee, and Arizona — states with rapidly growing urban populations and a hunger for economic growth that exceeded any appetite to hold back historically suppressed racial minorities. Why, administrators in these states started asking, should faculty members get to decide when to teach classes if it means students have to wait extra semesters to take courses essential to their majors? Why should students with no family history of negotiating an undergraduate degree have to figure out for themselves which classes to take, in which order?

Starting in the mid-1990s, these campuses rewrote course maps, rethought student advising, grouped freshmen together by subject area, lifted registration holds for petty library fines, and found a variety of other ways to ease the students’ path through the campus bureaucracy.

After 2008, Georgia State was able to take these ideas and turbocharge them with the analytical powers of emerging new data technologies. The incoming president, Mark Becker, was a statistician by training who understood the power of creating successful models and scaling them across tens of thousands of students. His student success guru, Tim Renick, had been a singularly gifted classroom teacher and needed no persuading that lower-income and first-generation students were worth believing in, because he’d seen over and over how they responded to his teaching and thrived.

Renick couldn’t stomach a system that knowingly sold students a bill of goods, inducing them to load themselves up with debt for a degree that at least half of them stood no chance of getting. What started as a moral imperative to graduate large numbers of traditionally underserved students has become a national rallying cry, a challenge to other institutions to ditch the old excuses and follow Georgia State’s lead.

The wonder of Georgia State rests on a simple idea: that if students are good enough to be admitted, they deserve an environment in which they can nurture their talents regardless of personal circumstances.

Georgia State’s pioneering innovations have been written up in The New York Times and discussed with fervor at hundreds of education conferences. Public universities nationally are in broad agreement that the revolution in downtown Atlanta points the way to all their futures. These breakthroughs came about thanks to the interactions of those educators who threw themselves into the work and stuck with it despite long hours and modest compensation, because they couldn’t imagine doing anything more meaningful with their lives; and of course the role played by the students, whose tenacious example and unbreakable will either inspired important changes or exemplified their life-changing benefits or, often, a bit of both.

Andrew Gumbel worked as a foreign correspondent for Reuters and the British newspapers The Guardian and The Independent. He is the author of Down for the Count, Oklahoma City, and Won’t Lose This Dream.

Copyright © 2020 by Andrew Gumbel. This excerpt originally appeared in Won’t Lose This Dream: How an Upstart Urban University Rewrote the Rules of a Broken System, published by The New Press. Reprinted here with permission.

This article is featured in the November/December 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: The future looks bright: GSU has gained a reputation for graduating large numbers of students who are poor, Black, and struggling. (Steve Thackston/staff photographer at Georgia State University)

Learning the Wrong Lesson about Education Reform

Detroit, 1979. U.S. auto companies were being threatened by foreign competition, and the Motor City became a symbol of American industrial decline. Chrysler would be subjected to its first (but not last) government bailout; the Ford Motor Company was about to lose $1 billion for that fiscal year, and at least as much again in 1980; and GM’s profits were expected to plunge by a breathtaking $2.5 billion. Meanwhile, Japanese automakers were gaining market share; Toyota would soon surpass GM as the world’s largest car company. (A similar scenario played out in other industries too, especially consumer electronics and the copier industry.)

Then, as now, the convenient scapegoat was the rank-and-file employees — in Detroit’s case, the unionized workers whose relatively high wages and ostensibly poor work ethic were initially blamed for the automakers’ problems. Only as Japanese wage rates reached parity with those in the United States and Japanese automakers began hiring American workers for their U.S. plants did some Detroit auto executives begin rethinking the narrative of blue-collar failure.

In 1980, an NBC documentary, If Japan Can, Why Can’t We?, served as a wake-up call for American industry. The documentary introduced the methods of a little-known American quality expert by the name of W. Edwards Deming to an American audience. Deming had helped Japanese companies rebuild following World War II, becoming a hero in Japan. Responding to an urgent appeal from the new president of Ford, Deming flew to Detroit and, during the next few years, proceeded to rip the lid off of the prevailing assumptions about the quality problems of U.S. companies. It is a testament to how desperate the auto executives were that they grudgingly embraced Deming’s message, despite the fact that he laid the lion’s share of the blame for quality problems on senior management instead of on labor.

Canned curricula have sucked the joy and creativity — and often the purpose — out of teaching and learning.

Deming was a quintessential outsider. Raised in Wyoming, Deming was trained as an engineer and physicist but became a pioneer in statistical sampling methods. At the peak of his popularity, he worked out of the basement of his modest home in Washington, D.C. At a time when American industry was becoming ever more siloed and finance focused, Deming advocated a collaborative, systems-focused, process-obsessed approach to management. While he was often derided as a mere statistician, Deming made a crucial breakthrough by linking the scientific (in particular, how to understand and manage the statistical variation that erodes the quality of all processes) and the humanistic (an intuitive feel for the organization as a social system and a collaborative, democratic vision of management).

Variation is as ubiquitous as air or water. But a cornerstone of Deming’s teachings was that only the employees closest to a given process can identify the variation that invariably diminishes quality and develop ideas for improving quality. Ordinary employees — not senior management or hired consultants — are in the best position to see the cause-and-effect relationships in each process, Deming argued. The challenge for management is to tap into that knowledge on a consistent basis and to make that knowledge actionable. To do so, management must train its employees to identify problems and develop solutions. Deming argued that management must also shake up the hierarchy (if not eliminate it entirely), drive fear out of the workplace, and foster intrinsic motivation if it is to make the most of employee potential.

What, readers may be wondering, does industrial improvement in the automotive industry have to do with the ongoing controversy and debates surrounding the quality of American education?

Since the beginning of the millennium, the story of education reform has been, in important respects, a business story. That’s how I, a longtime management writer, first got hooked on the subject. And I believe that the corporate-reform industry that is gaining ever-increasing influence on how American schools educate children has largely ignored the successful examples and strategies for improving schools that are hiding in plain sight. These distinct examples together form something of a quiet revolution in education. Even as the generative, systems-oriented ideas were finding their way into companies, inspired by Deming and like-minded management thinkers, some schools and school districts around the country were following suit. They were resisting the mandates, the punitive teacher evaluations, and, in some cases, even the standardized tests and were searching for — and finding — an alternative path.

But too many business reformers came to the education table with their truths: a belief in market competition and quantitative measures. They came with their prejudices — favoring ideas and expertise forged in corporate boardrooms over the knowledge and experience gleaned in the messy trenches of inner-city classrooms. They came with distrust of an education culture that values social justice over more practical considerations like wealth and position. They came with the arrogance that elevated polished, but often mediocre (or worse), technocrats over scruffy but knowledgeable educators. And, most of all, they came with their suspicion — even their hatred — of organized labor and their contempt for ordinary public school teachers.

What has led the mainstream education establishment astray is that it has adopted the wrong lessons from American business. Instead of learning from systems thinkers like Deming about the importance of ordinary employees — not senior management or hired consultants — the education establishment has looked to the top-down, hierarchical world in which employees are directed from above and manipulated with carrot-and-stick incentives.

The man whose ideas have permeated the DNA of American industry and society was Frederick Winslow Taylor, who was hailed by The New York Times as “the man who invented efficiency” — an early-20th-century mechanical engineer whose obsessive rationalism oversold the ability of science to improve productivity; undervalued the creative input of employees, especially hourly workers; and leveled its greatest ire against labor unions.

Taylorism even shaped public education. “[F]or better or for worse, Taylor’s influence ‘extended to all of American education from the elementary schools to the universities,’” writes Robert Kanigel, Taylor’s biographer.

Educational institutions have profoundly different goals and cultures and constituencies than businesses do, which makes them much less suited either to a free market model or to Taylorism. Educators are much more driven by social justice and job security than by money. Good teaching is as much art as science. Good education also is seen, increasingly, as collaborative and interdisciplinary. Last but not least, children are more vulnerable than adult employees or consumers to disruptions of the marketplace.

The Taylorite legacy is responsible for one of the most distorted and counterproductive received truths of the mainstream education-reform movement, one that blames teachers for the lion’s share of the problems that ail schools and has turned teacher bashing into a blood sport.

During the course of researching my book After the Education Wars, I asked dozens of sources — business leaders and education reformers of all stripes — what percentage of teachers they would consider to be “bad teachers.” When I asked Paul Vallas, a standard-bearer of the corporate-reform movement and the former superintendent of both the now all-charter New Orleans schools and the Bridgeport, Connecticut, school system, his answer surprised me: “The vast majority are excellent when provided with the curriculum, instructional models, and supports” they need.

It’s noteworthy that much of education policy over the last 30 years has been directed at identifying, punishing, and expelling a relatively small percentage of poor performers. In the process, the educational establishment has produced a set of policy mandates — including a constantly shifting round of punitive and ill-conceived performance appraisals that were linked to steadily shifting and often ill-conceived standardized tests — as well as canned curricula that have sucked the joy and creativity — and often the purpose — out of teaching and learning. They have not only subjected kids to round after round of testing and mind-numbing lessons; they have also proven deeply demoralizing for teachers — the vast majority of whom are capable educators who want nothing more than to improve their practice.

Instead of nurturing teachers to stay in the profession and improve their practice for the long term, the reform movement has focused on the effort to standardize teaching so that teachers can be easily substituted like widgets on an assembly line. In this context, it’s important to understand that behind the teacher-bashing is another Taylorite mantra that runs at cross-purposes with the aim of fostering an improved teaching corps: A unionized teaching force is a sure route to perdition. Better to maintain a revolving door than risk the possibility that teachers might join a union.

The result has been an unsustainable level of teacher turnover in both traditional public schools and charters — and in many districts, it is the best and most seasoned teachers who wind up throwing in the towel.

Even the conservative American Enterprise Institute recognizes that schools can’t fire (and hire) their way to better results. The total number of college graduates from Barron’s “highly competitive” or “most competitive” colleges is approximately 141,956 annually. If fully 10 percent entered into teaching for a two-year period before moving on to other careers, it would provide just 27,655 educators annually, 6 percent of the 438,914 teachers at work in the nation’s largest school districts (as of 2008). Simply put, schools have no choice but to work with the teachers they’ve got.

Part of the problem is that there has never been a consensus about the nature of the public school “problem.” One theory holds that American education has been “homogenized and diluted,” that it lacks rigor, and that the teaching force is wholly inadequate to the task — “too many” drawn from the bottom of their high school and college classes, too few experts in science and math, and not enough money to attract better candidates. Another theory argues that schools in middle-class and affluent areas are doing just fine, and it is the poor schools that are getting short-changed. Yet another theory argues that the standardized tests that were intended to inject more rigor into education are, instead, “driving instruction away from the development of … skills and thinking abilities increasingly needed” both in the workplace and in academia (emphasis added).

However you define “the problem,” there is little doubt that a global marketplace, one characterized by exponential technological change, and an increasingly diverse democratic society demand an education system that is capable of systematic adaptation and constant improvement. Schools must be able to prepare students both for the jobs of tomorrow and democratic citizenship. Yet, as of this writing, there is a growing realization that many of the remedies that have been touted for the past three decades have at the very least fallen short of these goals and have done little to improve American education overall, especially in the poorest neighborhoods.

For many of the schools that have defied the corporate-reform movement, choice — whether in public schools or charter schools — was focused on giving long-disenfranchised communities a voice in the education of their children. Integration also has been a key objective, as has imparting the values of democracy. The schools and districts that embrace a collaborative approach to continuous improvement take to heart the dictum of John Adams, who declared education to be “necessary for the preservation of their rights and liberties,” declaring that democracy depends “on spreading the opportunities and advantages of education.” Adams enshrined public education into the constitution of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, the first colony to pass a law requiring that children be taught to read and write and to require every town to establish a public school.

By contrast, the corporate education-reform movement has deep anti-democratic roots. For over 30 years, education reformers have focused on the utilitarian concerns of American economic competitiveness and whether schools will produce young people who meet the demands of industry and a global economy. In the process, these reformers have created a boom in the educational testing and technology industry, narrowed curriculum, and eviscerated the teaching of non-tested subjects, especially history and civics.

One of the biggest challenges facing education innovators who try to resist the corporate “reformers” has been striking the right balance between local democratic control and oversight by city, state, or federal governments. This is an ongoing project, but one well worth pursuing. Both the country and one of its greatest companies, General Motors, once thrived under just such a federalist system. While many of our institutions suffer from gridlock and dysfunction today, it is time to renew the struggle to regain the proper balance between central and local control, both in our government and in our schools.

America has entered a dystopian dark age, one fueled by bigotry and a celebration of ignorance. Schools must promote the love of knowledge and intellectual exploration over hate and philistinism. And they must relight the flame of democracy via classroom curricula and their governance structures.

Andrea Gabor has written for The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian, Harvard Business Review, and Fortune, among other publications.

Copyright © 2018 by Andrea Gabor. This excerpt originally appeared in After the Education Wars: How Smart Schools Upend the Business of Reform, published by The New Press, reprinted here with permission.

This article is featured in the September/October 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Roberto Parada / SEP

America’s School Nursing Crisis Came at the Worst Time

On a recent episode of the podcast RN-Mentor, Robin Cogan gave a less-conspicuous perspective on the current push for schools across the country to return to in-person learning: that of a school nurse. “When I look at opening schools,” she said, “and I’ve been very entrenched in it both at the state level and at the local level — it feels to me like we’re doing the biggest social experiment ever without an IRB [institutional review board] … our hypothesis: we are going to have kids and staff that are sick and, God forbid, die.”

Cogan, a Nationally Certified School Nurse from New Jersey, writes the blog Relentless School Nurse, where she’s been sharing useful information as well as stories from school nurses around the country. One has been tasked with providing their own personal protective equipment. Another spoke out against her school’s reopening plan in Georgia and resigned from her position. Cogan’s recent posts have revolved around a central theme: “It Has Taken a Pandemic to Understand the Importance of School Nurses.”

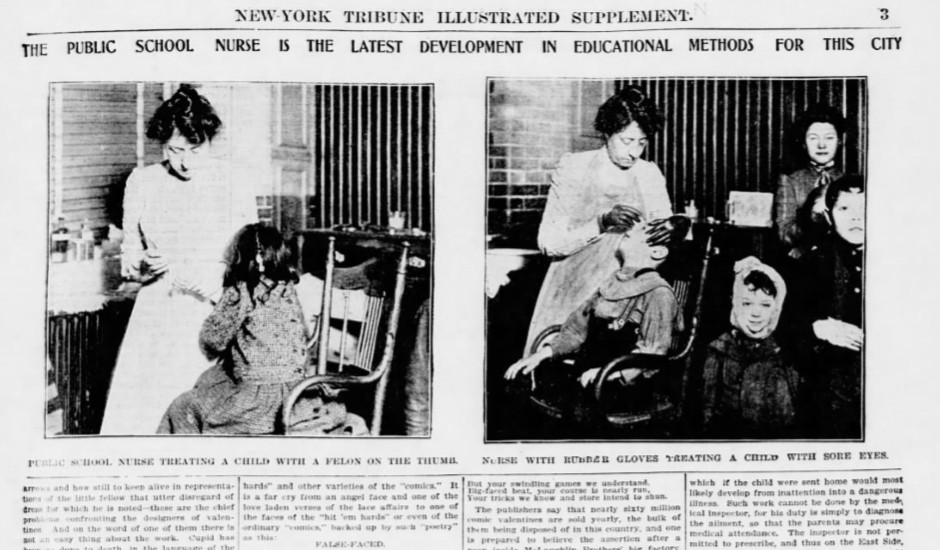

Around a century ago, school districts around the country were just coming to realize the value of adding a nurse to their ranks. In newspapers from Sacramento to Bloomington, Illinois to Washington, D.C., stories applauded school boards for often-unanimous decisions to budget for school nurses.

In 1918, The Charlotte News reproduced an entire paper read by a Miss Stella Tylski at a P.T.A. meeting: “There can be little doubt, that as the work of the nurse becomes better understood, there will be a greater demand all over the world for her services in the schools, for wherever she has made her entry, her value has been recognized.”

At some point in the last 100 years, however, school nurses fell off the list of public school priorities. In recent decades, many school districts have been eliminating qualified school nurse positions. According to a 2017 study from the National Association of School Nurses, less than 40 percent of schools employ a full-time nurse. In the western U.S., it’s only 9.6 percent. Twenty-five percent of American schools don’t even have part-time nurses.

As health considerations have taken center stage in conversations around education, it’s difficult to imagine a responsible plan for returning to school during a deadly pandemic that doesn’t include an on-site medical professional. Yet, for many of the country’s strapped schools, that may seem to be the only option.

Since its inception, school nursing has been predicated on public health.

School nursing in the U.S. began as a sort of experiment. At the turn of the century, when cities were becoming crowded with unsanitary slums that beckoned reform, public schools faced attendance problems stemming from influenza, tuberculosis, and skin conditions like eczema and scabies.

Although the New York Board of Health performed routine medical inspections of the city’s schools — and sent home children with troubling symptoms — there wasn’t a system in place to ensure students would recover properly. In 1902, The Henry Street Settlement, founded and led by nurse Lillian Wald, pioneered a program to place one nurse in four city schools — with around 10,000 students total — for one month.

The nurse was Lina Rogers, and her undertaking was a significant one. She was to perform her nursing duties at each school with makeshift facilities. At one school, she had only a janitorial closet as an office and an old highchair and radiator as examining furniture. At another, she treated students on the playground. “When children found out that they could have treatment daily and remain in school,” she wrote, “‘sore spots’ seemed to crop up over night.” Perhaps most importantly, Rogers made visits to students’ homes to discuss their ailments and treatment with their parents. She found it difficult, but necessary, to demonstrate medical care and explain the importance of hygiene in preventing illness.

At the end of the Henry Street Settlement’s month-long experiment, Rogers was appointed to lead a team of school nurses in the city. The month before she started in schools, the city saw more than 10,000 absences in a month. One year later, the number of absences for the month was 1,101.

Rogers became a chief advocate for school nursing, and cities across the country noted the Henry Street Settlement’s success. In 1908, The Spokane Press, among many others, applauded the New York school nurses for improving their city’s school attendance and “converting the truant into a studious pupil.”

Rogers wrote a textbook in 1917 detailing her work and giving guidance to the nation’s women who were setting out on this new occupation. She found the presence of health professionals in schools to be a vital aspect of public education’s mission to prepare American children for happy and healthy lives, but she recognized the tall order of staking the health of a community on one position. As she visited students’ homes, she found that things other than illness were keeping them from school, such as babysitting, housework, street crime, and neglect. “So the field of vision of the school nurse rapidly widened,” she wrote. “It was easy to see that if the school children were to be given even a fair opportunity of preparation for life’s work and duties, many things in the social life of the homes had to be improved. All the social problems of humanity, problems as old as the world, face the school nurse at the threshold of her work.”

Throughout the postwar years and the Great Society programs of the 1960s, school health programs were expanded to address drug abuse, students with disabilities, and mental health, among other public health inequities. School nurses became iconic fixtures of American schools, tasked with identifying and treating rising chronic illnesses.

But after the recession of 2008, school funding took a hit. Most states cut funding to education, and much of those losses have yet to be fully recovered. Since school nursing programs rely on school budgets — and few states mandate them — they’ve been quietly eliminated, consolidated, or replaced by untrained employees for years. Less than one-third of private schools employ any kind of school nurse at all.

American school nurses still find themselves advocating for public health amid dire circumstances. Most of them are paid less than 51,000 dollars per year, and the prospects of career mobility in the field are stark. A University of Pennsylvania study found that 46 percent of school nurses were dissatisfied with their opportunities for advancement. During the COVID-19 pandemic, however, nurses could be among the most important figures at any school.

In a phone call, the president of the National Association of School Nurses, Laurie Combe, mentioned that the first swine flu outbreak was discovered by a school nurse in 2009: Mary Pappas of Queens, New York. “We have expertise in collaborating with health departments to identify, record, and manage communicable diseases in schools,” she said. “We’re the public health practitioners closest to communities on a daily basis.”

According to Combe, nurses are a vital position in any school. She says they have, in many cases, already been working with schools on emergency operations planning. Throughout this pandemic, school nurses have informed their schools on the safe dissemination of food — to families who rely on free and reduced lunches — and technology and educational materials. They’ve continued to make sure students have access to their health providers and medications, as well.

“When schools don’t have the public health and infection control expertise of school nurses, they’re at risk of mismanaging the proper procedures. They risk mixing well children with those who might be symptomatic of COVID-19,” Combe says. “We know that when school teachers have to direct their time to managing health conditions, there is a loss of instructional time, principals lose administrative time. If students are unnecessarily dismissed, parents may lose wages. There is a cross-sector loss of time and money when there is not a school nurse present.”

Combe says the precautions that schools need to put in place in order to reopen during the pandemic are costly, like facility improvement, personnel, and PPE. The NASN is calling on the federal government to direct 208 billion dollars to support schools’ needs. “If schools are essential to reopen the economy,” she says, “then schools need the same financial support as businesses.”

The question of when it is safe for schools to reopen has different answers for different parts of the country, since schools are experiencing the burden of the virus at varying degrees. Cogan writes, “The bare minimum that we need to safely reopen schools is a stable, low rate of COVID-19 in the community [about 5 percent]; funding for and availability of basic public health precautions … and access to testing for students and school staff.”

In the midst of the most drastic public health crisis of our time, the forgotten heroes of our schools may prove to be an imperative component to our national recovery. If it did “take a pandemic to understand the importance of school nurses,” then perhaps that national lesson will endure this time around.

Featured image: American National Red Cross photograph collection (Library of Congress), July 1921

Teaching in the Time of COVID-19: What Have We E-Learned?

Life in America, and around the world, has changed dramatically in the face of COVID-19, and nowhere is that change more stark than in our institutions of learning. As communities entered into lockdowns and quarantines, educators were suddenly thrown into the position of adapting classroom plans (many of which had been written months in advance or were equipment-dependent) for an uncertain transition into e-learning. As the school year rolls to an end around the country, we gathered first-hand accounts from teachers on the frontlines, who shared the positives and negatives they’ve experienced. In short, what we have learned about e-learning?

Editor’s note: Some names have been changed to honor requests for anonymity. Those entries will be noted with an asterisk.

Dawn Jukes, Elementary Teacher, Indianapolis

Jukes has been teaching kindergarten and elementary school students from a wide variety of backgrounds for 23 years. She taught for the Indianapolis Public School system for 20 of those years.

Jukes: I teach for inner-city Indianapolis and two of my students don’t have WiFi at home, so they haven’t been able to do online e-learning. Out of 23 students, 10 have computers and the ones who don’t, try to do e-learning on phones and tablets. We have made packets twice as a second option. About 80 percent of our students picked up their packets the second time. I do Zoom two to three times a week and I usually have three to six students (out of 23) on it. I even do one evening, because a lot of my parents are still working. I’ve had parents tell me they work till six and have one tablet for three kids to do their e-learning on once she gets home. I send out weekly texts for free food pick-up options. I’ve had a couple parents express to me they’re very thankful. Phalen Leadership Academies (that I’m a part of) even delivers food on Mondays to our families who are in need.

I think my kids who get on my Zoom love seeing each other and having something different to do (I try to find different activities we can do together, or we learn about cities or countries I’ve visited, and talk about what is going on.) PLA also put together an e-learning website for students to use. It has 30 math and 30 ELA lessons per grade. I know some of my students definitely use it. I just wish all of them could.

Mary Ann Abramson, JAG (Jobs for America’s Graduates) Instructor

JAG is a nationwide high school (and in some cases, middle school) program, available in over 30 states. JAG “consists of a comprehensive set of services designed to keep young people in school through graduation and improves their success rates in education and career.” The program emphasizes project-based learning, collaboration, and internships, all of which were dramatically affected by the nationwide pandemic. Mary Ann Abramson is a JAG instructor at the high school level.

Abramson: This has definitely been a learning experience for me. My class model relies heavily on student interaction and input, so not having that at all felt like I was teaching blind. I couldn’t tell how the assignments were going, how much time it was taking students to complete them, or redirect when my instructions may have been misunderstood.

I think the three things that helped me the most through this e-learning pandemic time period are collaboration, self-care, and grace. This experience of trying to conduct school during a pandemic was new for absolutely everyone. Collaborating to share lesson plans, web sites, and stories of what has worked, and not, was helpful. It was truly humbling to see how teachers from across the nation were finding ways to share information and resources. Including students in the process was helpful as well, allowing me to structure assignments that truly met the needs of the students where they were as far as resources and emotional health.

This transitions nicely into my next piece of advice, the importance of self-care. Self-care is such a buzz word, but I found it to be a real lifeline for me and my family. Experiencing this, I made assignments for my students designed around finding a new activity, or revisiting an old one, that they could implement when they were feeling overwhelmed or increasingly upset about the way their school year ended. The feedback from students was very positive, and allowed for a good discussion at our weekly Zoom meeting.

The last one, grace, is something we all need to extend to one another, and ourselves, throughout this whole ordeal. Like I said before, this is new for all of us. Teachers, students, parents, even administrators… we’re all trying to do our best. We’ll come out of this better by working together, taking care of ourselves and granting one another a measure of grace along the way.

Dr. Lori Henson, Instructor, Indiana State University

Dr. Lori Henson is a seasoned journalist and an Instructor of Communication/Journalism. She’s taught in multiple formats, including online instruction, for three colleges over the past 17 years. She’s been with ISU since 2012.

Henson: 1. You can’t prepare for a moment like this.

I teach journalism at Indiana State University. I’m pretty comfortable with online education. My materials are online in a typical semester, and at Indiana State University, we use a course management system that students use to access materials and communicate about course assignments. All this familiarity made me think the transition to online teaching would be relatively seamless, even under the difficult circumstances. What I didn’t expect was how difficult it would be to reimagine how to teach journalism when the central idea of going places and talking to people isn’t possible. I had to work around those limitations by finding online and media content that would be useful and accessible for students and meet the course objectives. All of this done on a tight timeline.

2. Students are not alright.

One of my students is now the primary caregiver for her grandmother who was moved out of her nursing home as a precaution. Another student lost both her grandparents to COVID-19. An untold number of my students are paying their way through college as essential workers at grocery stores, factories, restaurants, warehouses, as delivery drivers, and even healthcare and childcare workers. Many have to fight for time using WiFi at public locations. Adjusting to online course work adds to their stress. When I realized what they would be facing, I determined it was not time to ask them to adapt to new apps, software, or even scheduled streaming meetings. It was not time to add to their workload, or even to their total news consumption about the pandemic. It’s simply not practical or kind.

3. The pandemic is offering an education of its own.

I cannot count the number of heroic acts of kindness, generosity, and public service our students and faculty and staff have initiated in this terrible time. Some of our university’s social work students and faculty are leading a mutual aid group in our community, to get resources to those at risk. Our students and faculty are marshaling their talents and labor toward serving others, researching solutions to all kinds of problems the pandemic presents, and keeping our world moving. Students and educators — in various ways, and with mixed results — are learning to cope, to build community, and to care for their mental and physical health in new ways.

4. We are resilient.

As an academic advisor, I have talked to dozens of students about plans for the months ahead. Almost without exception, students tell me they are bored, getting by, and looking forward to getting back to their classes and social lives. Faculty, thrown by the quick transition to online teaching, are looking forward to time to prepare for fall classes, whatever form they take. We are adapting. We are moving forward. And I believe we all have a new and grateful attitude about how much we mean to each other. We won’t take any of it for granted.

Wayne Stantz*, Community College Instructor

Wayne Stantz* and his wife Anne* both teach for a large community college system in the U.S. They have several decades of combined experience teaching both in the classroom and in several distance formats.

Stantz*: Whether it is college or K-12, class time still needs to be class time — plan your time accordingly and stick to it. It’s very common sense to say we need to follow time management, but in practice, we tend to let it go. Students (and people working) need to schedule time for study and keep that schedule. Our classes moved to a “virtual” environment, where we refer to online as the online distance model, and the virtual model is simulated classes taught through Zoom. Class sessions are held at the originally scheduled times, and these sessions simulate interaction for students with their peers and teachers. It’s important for students to keep to the originally scheduled class sessions, as even though they may not have a face-to-face class, they do have a schedule with time set aside for study and interaction with faculty.

This goes along with the idea that if a student is going to maintain that schedule and come to the virtual class, then engagement is also important. It is great to show up and sit in a Zoom meeting and watch, but if the camera and microphone are never turned on, as far as the teacher is concerned, the student might as well not be there. Teachers also need the student response to what they are saying and showing to guide the lesson. We respond to physical and verbal cues from our students to understand areas of inquiry or misinformation- if we don’t get those cues, we will assume everything we are discussing makes sense and move on to the next element. We may miss important learning moments because we don’t “see” the potential need for more clarity.

What I am saying is it is very easy for students to “ghost” — log into a class, keep the mic/video off, and then go do other things. I compare this to the student who comes to class but doesn’t engage, just sits in the room and looks at their phone/computer/sleeps. I laugh to myself when I hear teachers say, “Well, I never have that happen — I engage all my students.” No, you either bully your students to engage, or you don’t look around your room too often. In every room, there is the potential for students to fall through cracks. I’m not saying it always happens, but the potential is always there. Teachers wonder how do we engage all our students all the time, and now that technology makes it easy to “ghost,” that question is doubly hard.

Since the virtual meeting software records sessions, re-watching recordings of missed sessions has been a boon to students, and as a teacher, I look forward to shifts in teaching models when we return to the classroom. I would love for my “normal” classes to be recorded and be available to students who weren’t in class. The potentials for technology usage and different learning environments to co-exist are being proven in real time, instead of being argued about in curriculum and budget meetings, but I fear we will try to return to the old ways without consideration for the methods we are developing.

I’ve learned to be more flexible with deadlines, and that is saying a lot because I was already flexible with deadlines. Already I took the position of “I don’t know the outside life and issues of my students,” so I while holding them to a standard of expectation, I still gave them some ability to work around that. Now, with some of them being in the health or service industry, not only have their schedules gone out the window, when and how they engage with learning has, too. Numbers and attendance follows the online model more than the F2F (face-to-face) idea. Yet, even that has to be flexible — my F2F students weren’t expecting to take an online course — so the blended version of one (part online, part virtual F2F) is attempting to meet them and the situation head on.

In class, I have extroverts and introverts. The extroverts have to learn a bit of control because they can actually overwhelm the technology (the pacing of “phone” conversation is different than F2F). The introverts actually do well in the course — less direct peer intimidation. This doesn’t mean levels of fear of public speaking or engagement are gone, but the structure is different — there is a removal of the physical space and trappings. This allows them to have control of the environment they are in, to have control of their safety zones. And in that they might draw more comfort and not be overwhelmed by some of the environmental issues of a classroom full of people.

Assignments have to be different — online structured instead of classroom structured. I’m not saying that class activities can’t occur, but when half of your class may be unable to attend because of work, of family sickness, of technology issues, then the idea of having a 20-minute class activity that all participate in goes out the window — student led learning is now the model.

Giant packets of copied materials don’t work — they overwhelm and ultimately the teacher has to ask what did the student learn, and on a practical level, how am I going to get all that work back. I feel bad for my child going through this fake level of learning. He isn’t. He is doing his best to finish each generic assignment. The educational year is lost. I feel bad for the lost potential and wasted time. I suppose there were good intentions in the learning packets, but I’m not sure I see them as much as I see a rushed response to meet expectations.

The lesson I think I’ve learned is that we (America) could have done better. We squandered time and resources, hoarded money and floated false notions of liberty and freedom out of fear of change and selfishness. Teachers and students can’t do our best because there is such broad economic disparity between who has access to support and technology. This limits the ability to take advantage of what can be done. There is obviously poor leadership on all levels — not out of good intentions — I would never mind mistakes out of good intentions.

Helpful strategies for students?

Treat class time (virtual or otherwise) as a scheduled event. Time management is important, and so is learning. Be in your “class” when you signed up for it and treat it as if it is still going on.

Your teacher should still be there to lend support and explain the lesson — just because they sent home a packet, doesn’t mean they are off the hook. Send an email, talk online, but let them know that your learning is important to you and you need help

The hardest lesson for me was that not every assignment is worth breaking yourself for. Some things just don’t need that much stress over. Weigh the expectation and the goal — in the face of 40 equally poorly written assignments, letting go of depth isn’t letting go of learning. (That’s aimed at my child’s current school experience.)

Communication is important- outside of class, your teachers want to know what is going on so they can help you. Keep them up to date. Let them know where you have questions. There aren’t dumb questions.

READ EVERYTHING. Explore the world. Read the news (not just your favorite sources). Know what is going on and why. Ask questions.

Matt Brady, High School Science Teacher and founder of TheScienceOf.org, North Carolina

Matt Brady is a high school science teacher in North Carolina. He’s also the founder of the popular website www.thescienceof.org, which uses pop culture to teach larger scientific principles, and a co-founder of pop culture news site www.newsarama.com. Brady wrote The Science of Rick and Morty: The Unofficial Guide to Earth’s Stupidest Show in 2019.

Brady: I’ve learned again how deep inequality runs. I’ve “lost” students to work as their only, or both parents, have been laid off or live in fear of being laid off, and press their teenager to get a job because “we just don’t know.” And when in the days before we stopped physical school, asking students to participate in a survey about who had a device and WiFi at home wasn’t as thorough as it could have been, and students didn’t understand what it meant. A phone is not a device on which you can do schoolwork. A laptop is. But kids don’t want other kids necessarily to know that they don’t have one. Same with WiFi. You can’t watch hour-long videos for each of your classes on Cricket minutes, or pay-as-you-go plans. And that’s just technology and doesn’t touch food. Or shelter, or a place to go where you won’t get hit whenever someone drinks. As far as inequality goes, we’ve been yelling this for years and years, and this shined a white-hot light on it. Whether we do anything about it is always the question, but having worked in public education for a decade-plus, I fear I already know the answer. Probably just lots of words that make the people saying them feel better about themselves, but very little or no action.

There were, at least for my district, no plans ready for this, and I figure that was the same for many others. That’s…understandable given the tightness of budgets and how “war-rooming” would be a luxury, spending money to talk to consultants and pay staff to speculate about scenarios and how to respond. But if we can level this criticism at the administration, we can level it at every smaller organization that is an essential need: we knew this was coming. There was no plan. There was deferring to authorities, either local or state, who also had no plan. We were all Indiana Jones going after that truck in Raiders of the Lost Ark — we were all just making it up as we went along, and like Indy, we did okay. But…this is going to happen again. We’ll be remembered by history for how we made do on this one. We’ll be judged by history on how well we’ve prepared for the next wave of COVID, the next pandemic, or whatever emergency situation arises that requires long-term off-site learning.

This has reaffirmed that a lot of kids — despite the manic-ness of teenagers on TikTok and others — are not okay with this. Those of us who’ve chosen to stay in daily contact with our students are putting our training in “cries for help” to use and have quickly become experts at the “language” someone uses when they’re in trouble. The words not being said as well as the words being said. The order of the words. A shy student who’s desperately chatty. An e-mail from a student saying, “I quit.” Schools have amazing supports built-in for students, and it guts me that we’ve had to use them pretty much non-stop through all of this.

Related to this, I do have a lot of kids who are putting in the work who will probably admit that the work — the regular expectations of my class, of their math class, and others — have been their lifeline, their crutch to keeping something of a “normal” feel to their days and weeks. Some had issues, some had to bow out to work, and yes, some did ghost us, but overall, they kept at it. They kept learning. The future will be okay, ultimately.

Some kids like this, and respond better to online, at-home learning than in-room, in-school learning. I’ve seen some of my quieter kids, and some with challenging situations, utterly blossom and do some of the best work of their time in my class. For some, the distractions and social pressures of being in school were the issues. I’ve been humbled by how well some of my kids are doing.

Kids need to see that their teachers are vulnerable and that we’re in this together. This was not the time for teachers who get off on being dicks to their students to continue that, just online. I made a point to pull my class together as a community. I wrote a Corona Diary entry every day which was half stuff they needed to do, and have me journaling about the time, how I’m doing, and how I hoped they were doing. We had a class playlist so we can remember this time. I told them about how much Mother’s Day sucked for me since my Mom had passed away in December. I told them that I had up days and down days, and sometimes, all I wanted to do was just lie on my couch with the TV on, not paying attention to it. I held my due dates as flexible and offered them do-overs if their heads weren’t in the game when they had to do the assignment. I told them we’d all see each other again someday soon and laugh and remember this, and tell our stories to each other. And I was looking forward to it.

I learned that the public needed stability in all of this, and early on, some of that stability was provided by stories of “hero teachers” going above and beyond…the three percent or so of teachers who’d been pushed online. Those made people feel good for a while and we all laughed and smiled at teachers visiting students and writing on storm doors, and making cute videos and puppet shows, but then the public got tired of those stories and moved on, which was fine, because more and more of us were seeing those stories and feeling like we sucked if we weren’t doing those things if we didn’t have Pinterest-ready backdrops, lessons, and boards good to go. If our whole class wasn’t on Zoom at the same time or however the super-teachers were being shown to be super-teachers. A lot of us were doing the best we could, and it was nowhere near the story we were being told about “all the teachers.” As teachers, often portrayed as the bad guys and the problem, unless we’re taking a bullet for a student, this moment in the sun was…discomforting. And by the way, there have been some “struggling teacher” stories, but those aren’t as feel-good and don’t make people happy, so they’re kind of buried.

A lot of my kids thanked me for that. For being human with them and to them.

I learned that this was not online teaching. These were not online courses. This was disaster response.

Featured image: Shutterstock

We’ve Been Looking for Carmen Sandiego HOW LONG?

This much we know about Carmen: she’ll ransack Pakistan and run a scam in Scandinavia. It’s much harder to figure out one simple thing: where is she? 35 years ago this week, kids started hunting for that sticky-fingered filcher with a thing for thievery. But did anyone expect that a computer game aimed at teaching geography would spawn multiple sequels, game shows, insanely catchy theme songs, and animated series and specials, including a new one for Netflix? Carmen Sandiego may have criminal tendencies, but she’s a legitimate phenomenon. Let’s crack the case of how Carmen stole the limelight.

Clue #1 – The First Game: The original Where in the World Is Carmen Sandiego? game was developed by Broderbund for all of the popular home computer platforms that were available in the early 1980s; that includes Commodore 64 and the Apple II, which was particularly popular in schools. The initial idea of an adventure for children came from programmer Dane Bingham; his co-workers Gene Portwood and Lauren Elliott joined the project, working on the concept of a game where you catch one criminal at a time. Gary Carlston, the co-founder of Broderbund, had traveled in Europe when he was younger, and suggested integrating geography into the game. They brought in writer Dave Siefkin, and Carlston instructed him to use the World Almanac for reference. Eventually, the story of a rookie detective (the player) tracking down a network of thieves and their elusive leader (the red-hat-wearing Carmen) across 30 countries using geography, pun-heavy clues, and a World Almanac (that came packed with the software) resulted in the original 1985 version of the game.

The game became an immediate hit upon release. Embraced by schools, it managed to do the nearly impossible thing of being a fun mystery while teaching the player as it went along. In the first 10 years, the original title would end up selling four million copies. Magazines like Compute! and Info heaped praise on the game. The Software Publishers Association called it the Best Learning Product of 1985.

Clue #2 – The Game Becomes a Franchise: You don’t have to be ace detective to know that a hit product usually means a hit sequel. In the case of Carmen Sandiego, that one game turned into an entire line of software. Since 1985, more than 20 official games have been released, with some broadening the scope to include history, math, and science. The series has earned over 100 awards throughout its existence.

Clue #3 – The Franchise Switches Identities: In 1991, PBS launched Where in the World Is Carmen Sandiego? as a TV game show. Bright and colorful and combining clues with animated villains, music, and sketch comedy, the show became a huge hit in its own right. Over five seasons and 295 episodes, it pulled in dozens of Daytime Emmy nominations, seven Emmy wins, and a 1992 Peabody Award. Without a doubt, the most memorable element of the show is its criminally catchy theme song, a title number by the vocal group (and program cast members) Rockapella. A spin-off, Where in Time Is Carmen Sandiego? ran for two seasons of 115 episodes following World.

Clue #4: She Made a Move to Saturday Mornings: With the games selling spectacularly well and the game show sailing along, Carmen was next discovered hiding out on Saturday mornings. Where on Earth Is Carmen Sandiego? launched on the Fox Kids block in February of 1994, backed by the support of Fox’s other blockbuster Saturday morning shows, X-Men and Mighty Morphin’ Power Rangers. The titular character was voiced by showbiz legend and EGOT holder Rita Moreno. As the four seasons of the show ran, Carmen turned into more of an antihero than straight-up villain.

Carmen Sandiego: To Steal or Not to Steal runs on Netflix. (Uploaded to YouTube by Netflix Futures)

Clue #5: She’s Back for the Streaming Age: Carmen Sandiego never really had a cultural dormancy period since the character and franchise broke through in the 1980s. Even today, Google and The Learning Company continue to develop gaming content. But the series popped up on the broader cultural radar again last year with the launch of the Netflix animated series, Carmen Sandiego. The modern Carmen (voiced by Gina Rodriguez) is now a Robin Hood type character, outsmarting both the detectives of ACME and the agents of her former criminal organization, V.I.L.E. Characters from every level of the franchise, including the games, the previous animated series, and even the game shows, appear in the series. There have been two complete seasons; on March 10, Netflix debuted a special interactive episode, “To Steal or Not to Steal.”

Today, Carmen Sandiego exists in that sweet spot of being both Gen X nostalgia and a familiar entity to schoolkids. Books, board games, and comics have continued the mission of teaching young people about their word through entertainment. Rumors continue to swirl about possible feature film adaptations, with Sandra Bullock and Jennifer Lopez both having been attached at various points. With the Netflix series set to continue and no real end in sight for the computer games themselves, the answer to “Where is Carmen Sandiego?” is actually pretty easy. She’s here to stay.

Is Your Child’s School Being Unfairly Penalized?

No moral intuition is more hardwired into Americans’ conception of economic justice than equality of opportunity. While some of us may be rich and others poor, we are willing to accept such outcomes as long as everyone has an equal shot at success. The moral legitimacy of the market’s distribution of income rests on a presumption that our system rewards ingenuity, hard work, talent, and risk-taking rather than race, class, family connections, or some other advantage we consider unearned, illegitimate, or unfair.

“In every wise struggle for human betterment, one of the main objects, and often the only object, has been to achieve in large measure equality of opportunity,” declared President Theodore Roosevelt in a speech in Osawatomie, Kansas, in 1910, laying out the “square deal” he believed was due to all Americans.

In a speech later that year, Roosevelt took pains to reassure members of the New Haven Chamber of Commerce that his notion of equal opportunity fit squarely within the context of a market economy. “I know perfectly well that men in a race run at unequal rates of speed. I don’t want the prize to go to the man who is not fast enough to win it on his merits, but I want them to start fair.”

For the first time in American history, the steady march toward greater equality of opportunity seems to be headed in the opposite direction.

Equality of opportunity, of course, taps into the conception Americans have of themselves as a people who fought one war to shake off the tyranny of a British monarchy and aristocracy and another to shake off the chains of slavery, a people who welcomed wave after wave of ambitious immigrants yearning for a better life. Yet there is now a sizable and growing body of evidence that, despite elimination of most legal barriers to equality of opportunity, the luck of which parents you were born to continues to play an outsized role in determining economic success. Whether it’s by way of the genes we inherit (nature) or the circumstances in which we are raised (nurture), the results of this parental lottery are more important than ever in determining our natural capabilities and the degree to which we are able to develop those capabilities and bring them to an increasingly competitive marketplace. Indeed, for the first time in American history, the steady march toward greater equality of opportunity seems to be headed in the opposite direction.

Our education system is no longer serving its historical role of equalizing economic opportunity and increasing social mobility. Rather, it has become an instrument by which children lucky enough to be born into favorable circumstances increase their economic advantage over those who were not.

It was 65 years ago that the Supreme Court, relying largely on evidence and expert opinion from social scientists, ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that sending black children to separate schools was inherently unequal. Now it is time to extend that constitutional principle and declare that it is no longer acceptable to organize and finance public education in a way that segregates poor children in separate schools.

Because of our reliance on local property taxes to fund public schools, and public school systems that organize schools around residential neighborhoods, we have a system that in many places provides less funding, less effective teachers, and worse facilities to poor students who require more resources and better teachers to reach comparable educational goals. Moreover, there is clear evidence from social science research that segregating poor children in the same schools deepens their disadvantage. The only practical way to end this class segregation in education is the same way racial segregation was ended — with a Supreme Court finding that segregating poor students in the same schools denies them the equal protection of the law guaranteed by the Constitution.

As it happens, the Supreme Court explicitly rejected that view in 1973 in a case that few remember today, San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez. In a 5–4 ruling, the Court — which only two decades before, in Brown, had recognized the importance of public education to a democratic society and a child’s success in later life — reversed course and declared that public education was not a fundamental right under the Constitution. It also found that discrimination on the basis of class did not warrant the same strict scrutiny as discrimination on the basis of race. Writing for the majority, Justice Lewis Powell worried that if public education were to be treated as a fundamental right, the Court would find itself on a slippery slope that would also require it to give similar status to housing and medical care.

It is time to revisit those issues. One reason is new evidence from social science studies showing that the socioeconomic characteristics of a child’s classmates are a better predictor of educational achievement than a child’s own socioeconomic background. Another is the change in case law. In the intervening years, there has been a long line of Court decisions striking down affirmative action plans at universities or guaranteeing parents control over their children’s schooling, in which the Court’s conservative majority recognized something that sounds very much like a constitutional right to education. With a series of education reform bills, Congress has also established a strong federal interest in ensuring that all students attain minimal levels of educational achievement, with a particular emphasis on low-performing students and school districts. All of these developments provide a solid legal basis to ask the Court to reconsider the issue and declare that Rodriguez was wrongly decided.

There is nothing sacred about the idea that municipalities and school districts have to have the same boundaries, or that public education needs to be funded primarily through property taxes. To assure equal access to an adequate education, the federal courts could require states to redraw school district boundaries in ways that would end desegregation by class and put rich and poor students in the same school systems. Courts could order states to devise statewide funding formulas that would begin to break the pernicious link between local property values, per-pupil spending, and educational achievement. And judges could even insist that the newly redrawn school districts rely on student choice for school assignments and make extensive use of magnet schools.

I don’t underestimate the political and legal difficulties in bringing about such a radical restructuring of public education. I am old enough to remember the bruising battles over busing, and I am aware that the process of bringing racial integration to public schools has hardly been a smashing success. Class integration would be no less challenging, but it is also no less of a moral imperative.

It is worth recalling that the campaign to overturn the separate but equal doctrine in Plessy v. Ferguson energized a generation of Americans in the 1960s. Overturning Rodriguez and establishing the fundamental right of all children to a decent education could be the legal issue that energizes a new generation eager to ensure that history continues to bend toward justice. It will take patience, persistence, and political courage, but this is the kind of defining moral issue that is worth the effort.

From Can American Capitalism Survive? by Steven Pearlstein, copyright © 2018 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Press.

Featured image: Shutterstock

All the Right Moves: Teaching Chess (and Life) to At-Risk Children

Talk to Orrin Hudson and you’ll hear frequent motivational phrases. “Taking is for losers, giving is for winners,” says Hudson, founder of Be Someone, an organization based in Stone Mountain, Georgia, that teaches chess to at-risk kids. Another favorite for troubled teens: “Think it out, don’t shoot it out. Brains before bullets.” His quip on why failure is part of learning: “Every master was once a disaster.”

As befits a champion chess player — Hudson was the first African American to win the city chess championship in his hometown of Birmingham, Alabama — his sayings are well-calculated. Capturing bishops and knights, to Hudson, is far more than a game. By teaching chess, he’s developing kids’ critical thinking skills and inspiring them to set high goals — to be kings instead of pawns. Every move has consequences, he likes to say, and the loquacious Hudson, a motivational mix of Garry Kasparov, Steve Harvey, and Yoda, has shared that message with roughly 65,000 kids since forming his organization in 2001.

“I’m teaching them that this is a brain game, and you win or lose based on the decisions you make,” says Hudson, author of One Move at a Time: How to Win at Chess and Life. “It’s not where you line up, but where you wind up. Make every move your best move.”

See? There’s those catchy phrases again. It’s no wonder kids respond to his teachings.

“He’s very charismatic,” says Nataki Montgomery, a longtime Be Someone volunteer whose daughter, a Hudson chess disciple, is now an attorney in New York. “He makes it fun. I’ve seen kids that don’t know anything about chess get really engaged.”

At his camps, Hudson starts with an overview of the game. Sometimes he’ll provide instructions using a life-size chessboard; other times he wanders the room, observing and critiquing as kids play. At one camp he played 59 games at once.

“People watch him and they’re drawn in,” says Montgomery. “He’ll say things like, ‘See what he did? Now this is what I’m going to do.’ People are wondering, What’s the next move going to be? And you’re pulled into the game.”

Hudson’s brother first taught him to play when he was a boy in Birmingham. He was one of 13 children raised by an overburdened mom, and the state moved him in and out of foster homes. By age 14, he was committing petty crimes in a gang. “Mostly we were stealing food,” Hudson says. “One day, we were about to break into this truck and the police came. We took off running. And I thought, This is crazy.”

Things changed when he met a chess enthusiast named James Edge.

“He was a white teacher in an all-black high school,” Hudson says. “He taught me chess and purchased me a thick chess book that I read cover to cover. It was the first book I really read. So I started becoming a reader, and started making better grades and doing well.”

By playing chess, Hudson developed discipline, focus, curiosity, and patience. “I owe my life to James Edge,” he says. “He helped me improve my game because he would play me all the time. He would teach me stuff, and I started thinking for myself. Once you do that, good things start to happen. That was a game changer for me.”

After high school, Hudson served in the Air Force as an airplane mechanic and crew chief, and later spent 6 years as a state trooper in Alabama. He was running a used-car business when he saw a news story in 2000 that altered his life. At a Wendy’s restaurant in Queens, New York, five employees were killed, execution-style, during a robbery; two others were shot and left for dead. The criminals stole $2,400. Even though he didn’t know the victims, Hudson couldn’t shake the cruelty and waste.

“Life has value, and to shoot seven people in the head for $2,400, it ripped my heart out,” he says. “It was a turning point in my life. I said, ‘I’m going to create a program and teach people to put brains before bullets. I’m going to teach young people that there’s a better way.’”

He sold his car business, started the nonprofit, and over the past 18 years, Hudson has helped change the lives of numerous Georgia kids. They are students like Cecil Davis, who credits Hudson for his transformation from goof-off to stellar student after attending his chess camps. Or Aaron Porter, a young man who was nearly jailed for attempted murder. “His father was locked up for 16 years, and he came home, and they got in a fight,” says Hudson. “But the judge gave him one more chance to get his life together.” After working with Hudson, Porter won a state chess championship, despite losing his queen during the match.