Rockwell Video Minute: Elect Casey

See all of the videos in our Rockwell Video Minute series.

Featured image: (Norman Rockwell / © SEPS)

The Five Closest U.S. Presidential Elections

In racing, whether horse or auto or foot, they call it a photo finish. That’s a result that’s so close that it’s almost impossible to discern with the naked eye, necessitating careful examination of a still picture to determine the winner. While you can’t resolve an election with a simple photo, history is loaded with contests that have been, at many points, too close to call. Though the rule of law and an orderly transition have been the norms in the United States since its inception, that’s not to say that arriving at a winner hasn’t on occasion been a rocky or contentious ordeal. With that in mind, here are the five closest presidential elections in the history of the United States.

Before digging in, one acknowledgement that you have to make is that the election is decided by the quirk of all quirks, the electoral college. The electoral college’s votes decide the outcome of the election, regardless of the outcome of the popular votes; though most presidential elections have “matched up” in terms of who won both the popular and electoral majorities, there have been five separate occasions when the “winner” lost the popular vote but was nevertheless conferred the presidency by the electoral college. Since the college is the final arbiter of victory, this list will be concerned with the closet elections in terms of the college; if you’re curious about the five closest in terms of the popular vote, those were: Kennedy over Nixon, 1960 (popular margin of 500,000 votes); Garfield over Hancock, 1880 (7,368 votes); Gore over Bush, 2000 (Gore had 500,000 more votes, but lost via the electoral college); Tilden over Hayes, 1876 (if you’re saying you don’t remember a President Tilden, you’re right; Tilden’s 250,000 more popular votes couldn’t tip Hayes’s electoral victory); and John Quincy Adams over Andrew Jackson (just wait).

So then, here are the closest presidential elections in terms of the electoral college.

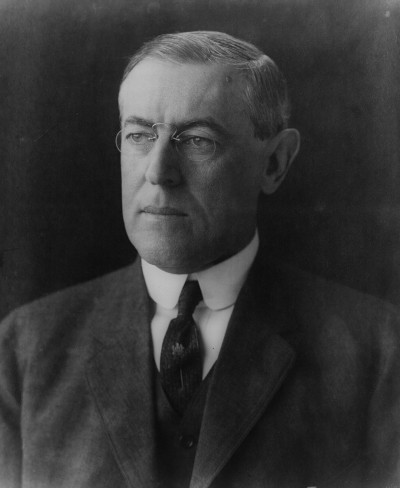

5. Woodrow Wilson vs. Charles Evans Hughes (1916)

Hughes was the former Republican governor of New York and a Supreme Court justice, and Wilson was the incumbent president. Wilson campaigned heavily on the fact that he had thus far kept the U.S. out of World War I. Ultimately, the desire to keep America out of the war proved to be too strong a force for Hughes to overcome. Wilson received 277 electoral votes to Hughes’s 254. In a historic bit of irony, the U.S. was fully immersed in World War I by April of the following year.

4. John Adams vs. Thomas Jefferson (1796)

Adams and Jefferson had a complicated, sometimes fiery, relationship. They were friends in the Continental Congress, served under first president George Washington together (with Adams as vice president and Jefferson as secretary of state), and later became bitter political rivals. Though they eventually mended fences and had years of correspondence with one another before dying on the same day (July 4, 1826), the 1796 election was one of their first heated moments of competition. Washington had the opportunity to run for another (third) term, but opted out. Adams and Jefferson both ran with running mates, but by a quirk of the rules that would later be altered in 1804 by the 12th Amendment, electors of the electoral college could vote for each person separately regardless of running mate, giving Adams 71 votes and Jefferson 68. By the rules as they stood, Adams became president, and his opponent became his vice president.

Honorable Mention: Thomas Jefferson vs. John Adams (1800)

This doesn’t quite count because of its overall strangeness, and it’s a situation that wouldn’t happen again today due to rules updates and the 12th Amendment. In a rematch of 1796, Jefferson and Adams ran against one another. However, this time there were formalized tickets, and Jefferson ran with Aaron Burr, while Adams had Charles Pinckney as his running mate. The rules being what they were, electors could cast votes for the individuals, rather than the ticket, so it ended up that Jefferson and Burr were tied with 73 electoral votes. That led to the election being decided in the House of Representatives, with Alexander Hamilton famously influencing the vote for Jefferson (the events of the election were described, albeit in a somewhat fictionalized manner, in “The Election of 1800” in Hamilton: An American Musical).

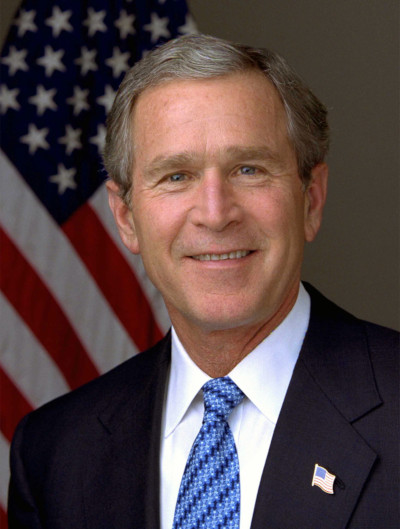

3. George W. Bush vs. Al Gore (2000)

We’ve already established that Gore won the overall popular vote. Of course, it all comes down to the electoral side. At issue was the fate of Florida’s 25 electoral votes, which would be the tipping point for either candidate. Things were so close that Gore called Bush to concede, and then took his concession back. Florida went into a statewide machine recount, as the popular vote would determine the disposition of the electoral vote; Gore also asked for a manual recount in four crucial counties. The Bush campaign sued to stop the recount, which triggered a run of decisions and appeals that went up to the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court ordered the recount stopped by December 12; at the stoppage, Bush was ahead by 537 votes. Florida’s electoral votes went to Bush, and he became president by a margin of 271 to 266.

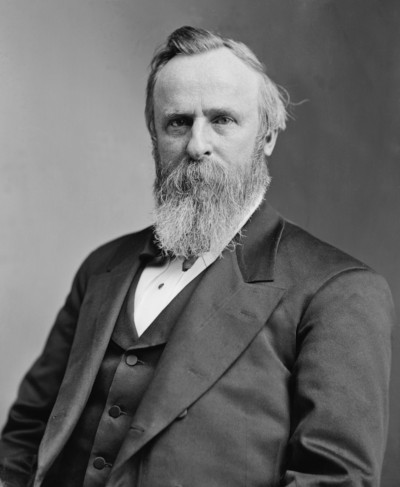

2. Rutherford B. Hayes vs. Samuel Tilden (1876)

This would be the closest election (in fact, the Post once called it the “worst election”) if it weren’t for the unprecedented action that followed in the Number One slot. The initial electoral count showed Tilden ahead of Hayes by a margin of 184 to 165. The 20 votes of Oregon, Florida, South Carolina, and Louisiana remained in dispute, with both sides declaring victory. Wheeling and dealing led to an agreement that’s called the Compromise of 1877; the states offered their electoral votes to Hayes if he would essentially end Reconstruction and withdraw remaining Union troops from the South. The deal was struck, and Hayes defeated Tilden by a single electoral vote, 185 to 184.

1. 1824: John Quincy Adams vs. Andrew Jackson

Going into 1824, there were four proper candidates: Secretary of State (and son of John Adams) John Quincy Adams, Tennessee Senator Andrew Jackson, Secretary of the Treasury William Crawford, and House Speaker from Kentucky, Henry Clay. Vice presidential candidates were voted on separately; in fact, Clay and Jackson would both receive votes in the category. The field of four candidates split the electoral vote; while Jackson initially had the most, he did not have enough for the electoral threshold. The breakdown was Jackson with 99, Adams with 84, Crawford with 41, and Clay with 37. With no majority winner, the decision then went to the House of Representatives, where each state would get one vote agreed upon by their reps. The 12th Amendment limited the field to three, so Clay was out. However, Clay, who hated Jackson, actively worked to get representatives from areas where he earned votes to support Adams. Adams won 13 states, and the presidency; Jackson finished with 7, and Crawford, 4. Jackson was enraged, as he had won the popular vote and the most electoral votes, but still lost. Making matters worse, Adams appointed Clay to secretary of state. Jackson would allege corruption, making it a centerpiece of his campaign; it helped him ride to victory in his rematch with Adams in 1828.

Featured image: andriano.cz / Shutterstock

How Nebraska Farmer Luna Kellie Was Radicalized Before the 1896 Election

In the late 1800s, one Nebraska farmer was beleaguered by an unruly farm, ten children, corrupt bankers, and indifferent politicians. She could have given up. But instead, Luna Kellie did something about it.

For most members of the Nebraska Farmers’ Alliance, a political advocacy group, the work of organizing occurred solely during the Alliances’ meetings and events. Yet for Luna Kellie, the Alliance’s secretary, the work often continued until the wee hours of the morning. As she later wrote in her memoirs, “if I had extra time when others were asleep, I would devote it to writings for the papers.” Kellie’s work for the Farmers’ Alliance eventually drove her to become a leader in the larger populist movement that swept through the U.S. during the 1890s. Yet even as she took on more responsibility, her political life and home life continued to intersect in the same way they had during those late night writing sessions. While Luna Kellie is far from being the most famous of the populist leaders, hers is the story of a woman driven to political action by personal hardship, making it particularly emblematic of the American political climate in the lead up to the pivotal 1896 presidential election.

St. Louis was a crowded town in 1876, and both Kellie and her husband J.T. felt that their dream for a safe and prosperous life was becoming more and more improbable in the industrializing city. So when the couple read a railroad advertisement for cheap homestead mortgages in Nebraska, they jumped at the opportunity. As Kellie wrote, “It seemed to me a great chance to see a beautiful country like the pictures showed and have lots of thrilling adventures.” A new life on the prairie also carried with it the promise of financial stability, a safe home, and a happy family. But in reality, Kellie’s new life was anything but the Little House on the Prairie. Instead, the newly Nebraskan farmer found that her farm’s success and her family’s well-being were at the whims of railroad magnates, cutthroat capitalists, and financiers in faraway states.

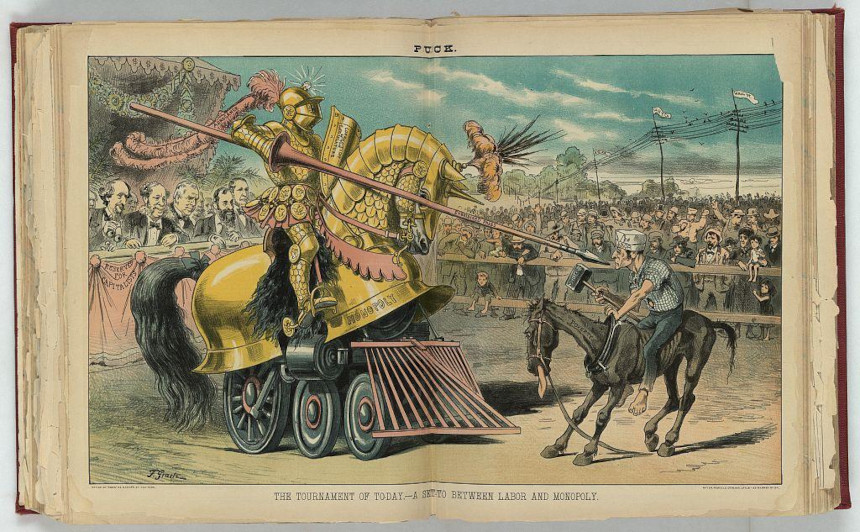

The decades after the Civil War promised a better life. Yet while the end of the 19th century was a time of widespread expansion, it was a time of even more widespread corruption. For freed African Americans, this corruption came in the form of Jim Crow regimes and new systems of oppression. For immigrants, it was political machines and decaying slums. For farmers — such as Kellie — corruption was apparent in the practices of railroads and banks that jockeyed for economic dominance over the vast expanses of the America west.

The end of the 19th century is called the Gilded Age on account of the decadence exhibited by urban capitalists such as Andrew Carnegie and John Rockefeller, yet this same monopolistic impulse extended across the country. Kellie was quick to point out how such corruption was at play in Nebraska, writing that

even after they [the railroads] had made 4 times the necessary ‘expenses’ had they [only] been content with a profit of 1 million a month instead of 2. If they knowing the farmers were raising their stuff for them below cost of production had said we will divide the profit on each haul of wheat and corn each carload of stock with you we would not only [have] been enabled to keep our place and thousands more like us but would have been enabled to live in comfort and out of debt.

One bad harvest was all that stood between most farmers and financial ruin, a fact that hung like a shadow over Kellie and her family. Midwestern homesteads were plagued by environmental hazards, ranging from crop-eating grasshoppers to tornadoes and disease. Kellie experienced all of these trials, with the extra challenge of raising ten children at the same time. Additionally, the mortgage on Kellie’s homestead was handled by an apathetic bank in distant Boston. As the bank continued to raise interest rates, Kellie and her family faced the very real possibility of losing their land entirely. To combat this fear, she began selling vegetables in nearby towns as a source of supplementary income, yet she knew that quick cash was not enough to remedy the challenges her family faced. She had realized that her failure to find success and happiness in Nebraska was the result of an economic system that disempowered prairie farmers for the betterment of railroads, banks, and the bottom line. And so Kellie turned her energy towards organizing.

Farmers around the country were beginning to identify the systematic roots of their poverty (including Kansas farmers who eventually brought their issue to the House of Representatives). However, both major parties were controlled by northern industrialists who had no inclination to support homesteaders. As a result, the populist movement emerged in different pockets throughout the country, eventually coalescing as a third-party option to fight for the livelihood of farmers.

Though it may not have been clear at the time, Kellie was at the forefront of the populist movement in Nebraska. Both she and J.T. were members of the Nebraska Farmers’ Alliance, an organization that held town hall meetings and created literature that offered Nebraska homesteaders a voice in national politics. However, Kellie insisted that “the alliance at this time was not supposed to be political.” Instead, it was simply defending the work and lives of prairie farmers.

Still, Kellie continued to become more involved (much more than her husband) in the Farmers’ Alliance. She was elected as the organization’s secretary and took on the job of editing the Alliance’s newspaper, The Prairie Populist. In the paper, Kellie published biting condemnations of the railroads, bankers, and economic practices that had caused her family so much hardship. Her political awakening also extended beyond the needs of farmers. Kellie’s agency in the Farmers’ Alliance made her increasingly adamant about the need for women’s suffrage, and she soon took on the additional task of traveling to conventions around the country to fight for the vote. As The Scranton Tribune noted of one of her speeches, she “exerted her influence in favor of universal suffrage, undaunted by the fact that she was obliged to carry her baby with her during the long journey.” Kellie took on all of these new responsibilities while continuing to work on the homestead and raise her children, a feat that only strengthened the intensity of her political engagement.

As she traveled, Kellie earned a reputation for her fiery speeches. She was a songster, a type of public speaker who wrote political lyrics to well-known folksongs and would intersperse bits of verse throughout addresses. Luna traveled throughout Nebraska and its bordering states, engaging audiences of like-minded farmers with her urgent, song-infused speeches. The most notable of Kellie’s addresses was her “Stand Up for Nebraska” speech, which featured passionate lyrics about the deplorable practices of business monopolies and the financial security that Nebraska’s land should have provided:

Stand up for Nebraska! and shame upon those

Who fear the extent of their steals to disclose.

Who say that she cannot grow wealth or create;

But must coax foreign capital into the state.

Such insults each friend of the state deeply grieves:

Stand up for Nebraska and banish her thieves.

Through the Farmers’ Alliance, Kellie found her political voice to speak against the “foreign capital” of railroad companies and the larger wealth gap that was present throughout the United States. However, as the populist movement ballooned into a national third party, Kellie was quick to realize that the local roots and honest message of the Farmers’ Alliance was being corrupted. In the lead-up to the 1896 presidential election, the wildly successful populist candidate William Jennings Bryan agreed to combine forces with the Democratic Party and run as their candidate. So-called “fusionists” were in favor of this decision. People like Kellie, who believed that the populist movement’s central mission of helping farmers was being betrayed, did not.

Kellie continued organizing for the Farmers’ Alliance, but her premonitions were partly realized. Bryan lost the 1896 presidential election, and soon thereafter the Populist Party lost steam. It was perhaps the movement’s only chance at success on a national scale, and it was squandered. The community organizing that was the bread and butter of the populist movement faded into obscurity, and soon enough the Nebraska Farmers’ Alliance also disbanded. Kellie continued speaking at conventions and fighting for women’s suffrage, but her political fervor waned.

Kellie continued working on her homestead, and many years later wrote a memoir for her family (which has since been published and serves as the principal source for this article). Quite poetically, she scribed the story of her life on the back of unused Farmers’ Alliance certificates. In its closing pages, Kellie offers a disillusioned soliloquy to the results of her political work. She writes, “And so I never vote [and] did not for years hardly look at a political paper. I feel that nothing is likely to be done to benefit the farming class in my lifetime. So I busy myself with my garden and chickens and have given up all hope of making the world any better.”

It is a heartbreaking sentiment coming from a woman who contributed so much to the populist movement, yet even Kellie’s own words might fail to capture the full scope of her impact. Luna Kellie’s goal was never to have a career in politics; still, she found widespread acclaim as a speaker, writer, and organizer. She was driven to politics by personal hardships, and even though the main cause she fought for may not have found success, she did succeed at giving a voice to the great number of people who faced problems similar to hers.

Featured image: Library of Congress

Too Old to Be President?

Age has been a big factor in this election.

For the first time, two candidates in their 70s are running for the nation’s highest office. And as you’d expect, both parties are claiming the other’s candidate is feeble, disoriented, and making no sense — i.e., too old for the job.

But 70 years doesn’t mean decrepitude as it once did. “Threescore and ten” years was the lifespan the Bible allotted to a human, but today’s 70-year-olds are different. They’re generally healthier, more active, and less mentally impaired than their parents or grandparents were at that age (if they even reached that age). Can an older candidate be less competent because of age? Certainly. But incompetence can be found in candidates of any age.

Perhaps the concern with age issue is really a concern over health: can a 70-year-old endure the stress that comes with the Oval Office?

The chances are good for either candidate because presidents appear to be unusually hardy.

For example, the Republican Party tried to recruit Dwight Eisenhower to be their presidential candidate in 1948. He turned them down, concluding he would be unelectable. They expected Thomas Dewey — the candidate they chose instead — to serve two terms. Which would make Eisenhower 66 years old if he chose to serve in 1956, and the country wouldn’t want someone that old.

But Eisenhower ran in 1951 and won. Three years later, he had a heart attack, but entered the race again in 1955, and won again. After he left the White House, he continued to play a dominant role in the Republican party until he passed away at 78.

Gerald Ford was 61 when he assumed the presidency upon Nixon’s resignation in 1974. He lived 29 years more. Ronald Reagan, aged 69 years at his 1981 inauguration, served two terms and lived 16 years beyond that. George H.W. Bush was 64 when he entered the Oval Office in 1989. He lived another 29 years.

And of course, there’s Jimmy Carter, who was elected at the tender age of 52. Thirty-nine years later, he’s still with us, building homes for Habitat for Humanity.

It’s significant that, of the six presidents who have celebrated their 90th birthday, four — Jimmy Carter, Gerald Ford, Ronald Reagan, and George H.W. Bush — served in the past 50 years.

But the number of decades is just one way to consider age. We can also judge a president’s age relative to the average lifespan of his time.

Up to the 1930s, Americans could think themselves lucky if they reached their 65th birthday. But our lifespan has continually lengthened; since 1920, the average American has gained 25 years of life.

Historians have estimated that, in the centuries preceding the 1800s, the average human lived just 35 years. The number is surprisingly low because it is calculated from the ages of all deaths within a year. Nearly half of these deaths (46 percent) were among children under the age of five, which lowered the average age of mortality for adults.

One researcher has concluded that a more realistic average lifespan of a 20-year-old American in 1800 was 47 years — still not a long life. Which is what makes John Adams so exceptional. Adams became president at the age of 61 — fourteen years beyond his expected lifetime. And he lived 25 years beyond his presidency!

Adams’s son, President John Quincy Adams, lived to 80. Thomas Jefferson reached 83, and James Madison saw his 85th birthday.

Today, the average American lives 78.54 years. But an American male who reaches the age of 65, according to the National Center for Health Statistics, has a good chance of living another 19 years.

Which means either candidate might be likely to live to the age of 84 – or beyond.

It’s possible that presidents in their 70s will be looked on more favorably as the proportion of elders in the population increases. By 2060, a quarter of the U.S. population will be over 65 years and old, and the average American lifespan will have risen from 74 to 85 years.

Children today may live to hear candidates someday complain that their 100-year-old opponents are too old to be president.

Featured image: John Adams, Dwight Eisenhower, and Andrew Jackson, three of the older presidents when they assumed office (Adams: National Gallery of Art; Eisenhower: Wikimedia Commons; Jackson: whitehousehistory.org)

Saturday Evening Post History Minute: The Greatest Political Comeback in American History

Featured image: Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge (Library of Congress)

Are You Barred from the Polls by Obsolete Law?

In this 1960 editorial, the Post urged states to eliminate stringent residency requirements and other rules that disenfranchised voters.

Our ridiculously outdated state voting laws are responsible for a mass disfranchisement of 13 percent of the nation’s total potential voting force.

When these laws were enacted, many of them a century and more ago, we were a less mobile people, and there was perhaps justification for requiring a person to live within the state for one and even two full years before being eligible to vote — as most states still do. But in these days of frequent job transfers and family moves, such waiting periods are far too long.

Similarly there is no valid reason why an otherwise qualified voter should forfeit his ballot simply because he has the misfortune to be incapacitated or must make an urgent business trip on Election Day. Yet most states have no provisions for balloting in such emergency situations. Help must be extended to those voters who want to do their civic duty and can’t.

—“Are You Barred from the Polls by Obsolete Law?,” Editorial, November 12, 1960

This article is featured in the November/October 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Constatin Alajalov / SEPS

Should Uninformed People Be Allowed to Vote?

One of the basic tenets of American government is that all qualified citizens should be able to vote. We trust the American people to make the right choice.

But Americans’ faith in “the people” has been weakened in the past few years. A great division has yawned between the political parties, and it’s not uncommon to hear Americans claim that voters in the other party are just plain ignorant.

There’s no doubt that democratic elections are determined, to a degree, by ill- or uninformed voters — even though our public education system was created to avoid this. A recent poll showed most Americans don’t know basic facts about the Constitution. (A third of respondents couldn’t name a single branch of government or a single right protected by the Bill of Rights.) Even worse, people may be voting based on intentional disinformation.

In our earliest days, Americans limited the vote to a select minority of people deemed as “qualified.” The colonies only allowed men to vote who owned sufficient property and/or belonged to the correct church. After independence, the framers of the Constitution said nothing about who could vote; they left the question up to each state.

All of the new states kept some form of the old colonial restrictions. In New Hampshire, for example, only white males with £50 of personal property could vote. Virginian voters needed 50 acres of vacant land, 25 of cultivated land, and a house measuring 12×12 feet.

These restrictions were intended to create an electorate of presumably educated, responsible men. But the idea clashed with the principle of equality and, in time, voting restrictions eased. But many people were still prevented from voting.

In 1855, Connecticut became the first state to require voters to pass a literacy test. In 1921, New York required new voters to take a test proving they had the equivalent of an eighth-grade education. (About 15 percent flunked.) As late as 1959, the Supreme Court was ruling that such tests didn’t violate the Fourteenth or Fifteenth Amendments.

The problem with literacy tests was that they could be used for political ends. They were used largely to keep African Americans and recent immigrants from voting. At the turn of the century in Mississippi, 60 percent of Black men couldn’t read. But the county clerk was the sole judge of who was literate, and therefore nearly 100 percent of Black voters were denied the right to vote.

Literacy tests persisted until the 1965 Voting Rights Act prohibited the tests in states that had obviously discriminated against Black voters. Not until 1975 were literacy tests finally banned outright by Congress.

Now, almost everyone can vote, but how well-informed is the electorate? Over the years, surveys have tracked the surprisingly low level of voter knowledge. A 2010 survey found a third of respondents couldn’t tell if the Civil War came before or after the War of Independence. And today, one in five adults say they get most of their political news from social media, which often carries deliberate misinformation from domestic or foreign sources.

The chronic need for better educated voters causes an inherent problem in democracies, according to Jennifer Hochschild, professor of government at Harvard. In 2010, she noted all democracies believe informed voters are essential to good government while they continually extend suffrage to greater proportions of their people. But this tends to bring less informed voters into the electorate, which led to her ask, “If democracies need informed voters, how can they thrive while expanding enfranchisement?”

Recently the idea of an epistocracy — government by the knowledgeable — has been making a resurgence. In his book, Against Democracy, Georgetown philosophy professor Jason Brennan justifies the idea by arguing the public has a right to be protected from individuals’ stupid mistakes.

He compares electoral votes to jury votes. If jurors pay no attention during a trial, or assign guilt based on their first impressions, or develop crazy conspiracy theories about the case, or are simply prejudiced against the accused, they’re incapable of rendering an informed verdict. The judge would have the right to declare a mistrial. The same standard should apply to choosing the president.

Brennan says incompetent voters should not exercise power of fellow citizens. If politicians or voters can’t fulfill their civic obligation morally and effectively, they should be barred from office or the voting booth.

His solution would be to test the political knowledge of all voters. Those votes of anyone who passed the test would be counted as two or more votes. Brennan’s test would be drawn up by 500 randomly selected citizens.

Americans might not appreciate people with a better-than-average-knowledge of government having a louder voice in an election. Citizens who’ve enjoyed a privileged life and the benefit of a good education would outweigh the will of the disadvantaged. And voters who don’t pass the test would naturally assume the test-passers were throwing their weight behind the laws and politicians who would benefit themselves.

Fortunately, democracy — even with its ignorant voters — works better than expected. Economist Amartya Sen points out that democracies have the most stable form of government and never have famines. Other researchers have found democracies generally work to avoid conflict and are less likely to wage war with other democracies. They have less civil conflict, less terrorism, and fewer attacks against women.

And, according to Professor Hochschild, voters aren’t as ignorant as they’re presented. They may not know the workings of legislation, but they are knowledgeable on issues that are important to them. In considering an incumbent presidential candidate, they can always ask themselves if they are better or worse off than four years earlier. Experience can fill in gaps in education; voters learn election by election.

Most importantly, unequal representation is contrary to the very foundations of American democracy. As John R. Allen of the Brookings Institution put it, “The United States is grounded upon the idea that individuals are owed the equal opportunity to voice their opinion as we, through our elected officials, chart the course of our nation. This idea is foundational to our American values and informs a great deal about what it means to be a citizen of the United States.”

Democracy isn’t easy; it requires more attention and thought than many are ready to give it. President Kennedy believed voters should be far better informed, since, as he said, “the ignorance of one voter in a democracy impairs the security of all.”

But Winston Churchill was willing to accept democracy, and voters, as they were. After all, he said, “democracy is the worst form of government, except for all those other forms that have been tried.”

Featured image: roibu / Shutterstock

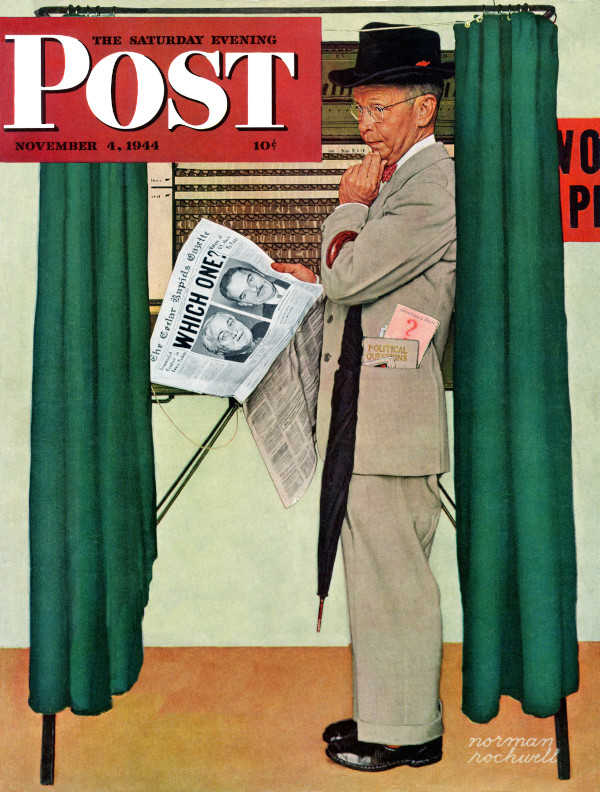

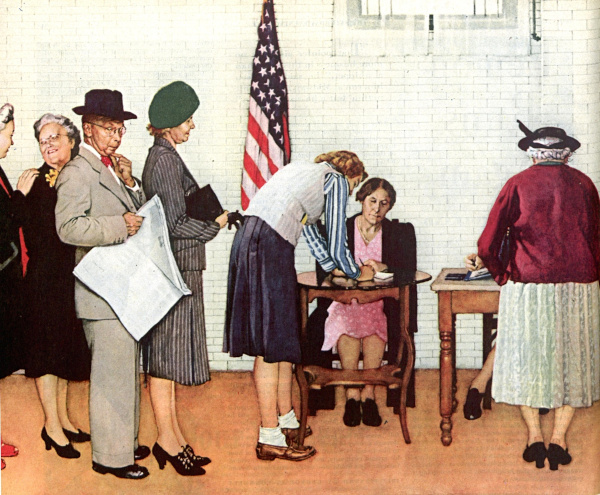

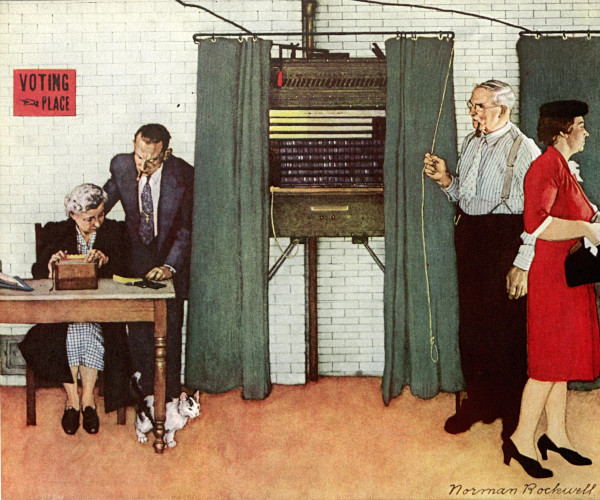

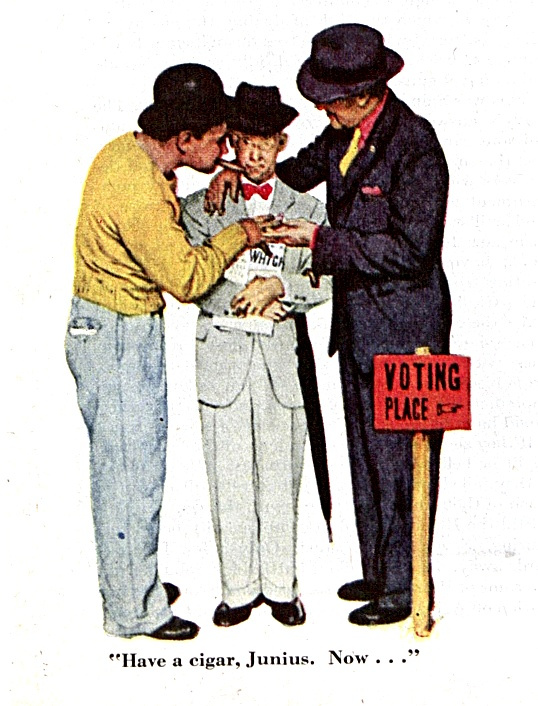

Norman Rockwell Paints America at the Polls

This description and illustrations appeared in the November 4, 1944, issue of the Post.

It would be hard to name anything more thoroughly American than the grand and glorious event which takes place on a certain Tuesday of every fourth November. To portray this national phenomenon, to capture its traditional spirit, we could think of no living artist better equipped with native understanding than Norman Rockwell. In his search for a truly representative background, Rockwell went straight to the heart of America; specifically, to Cedar Rapids, Iowa. By the time his pictorial preview was completed, he had created a new character: The human, likable citizen who adorns these pages and the cover of this Post. We have christened him Junius P. Wimple. You will, we hope, see more of him in Posts to come.

Rockwell, we reasoned, always knows his characters through and through. As Wimple’s creator, he knows how Wimple thinks, feels—and votes. Therefore, why not trick the artist into revealing Wimple’s secret, and thus learn the outcome of the election before it takes place? So we wired Rockwell: “Which one is Wimple voting for?” Promptly, the guileless artist answered by wire, collect: “For the winner.”

Vintage Ads: Elections in Advertising

The Royal Tailors

October 31, 1914

(Click to Enlarge)

While women may have been relieved to hear that they had equal rights when it came to tailored clothing (and that “the greatest designers of women’s clothes have always been men”), they wouldn’t have the right to vote for another six years.

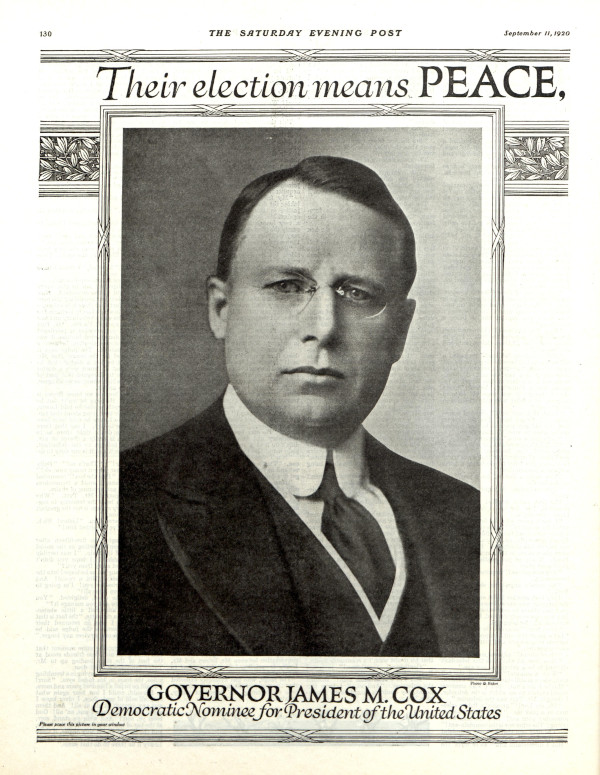

September 11, 1920

(Click to Enlarge)

Presidential candidate James M. Cox ran this full-page advertisement in the Post for the 1920 election, but his Republican competitor Warren G. Harding won in a landslide. Harding’s 26.2 percent victory margin remains the largest popular-vote percentage margin in presidential elections since the re-election of James Monroe in 1820, when Monroe ran unopposed.

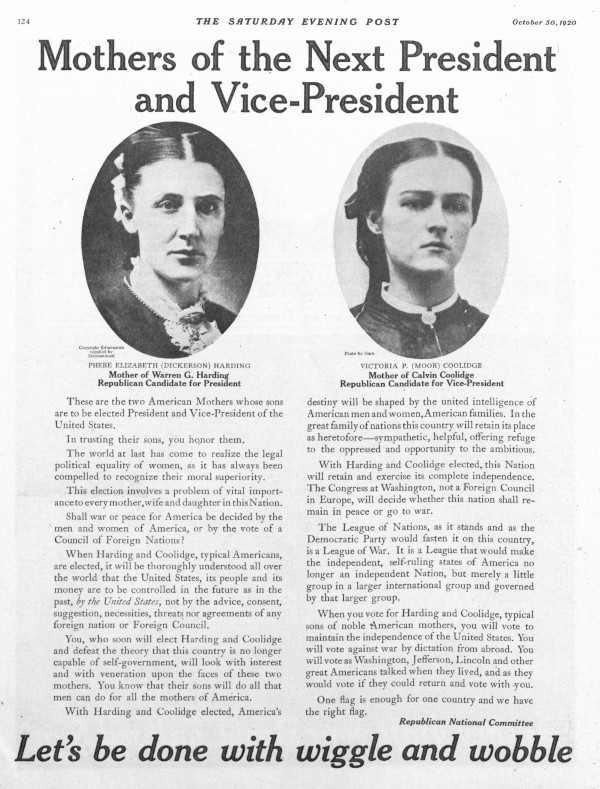

October 30, 1920

(Click to Enlarge)

The Republicans took a different tack in advertising their presidential candidate, featuring the mothers of Harding and vice presidential candidate Calvin Coolidge. Emphasizing their opposition to the League of Nations, the ad promised that “When you vote for Harding and Coolidge, typical sons of noble American mothers, you will vote to maintain the independence of the United States.”

Radiola

October 11, 1924

(Click to Enlarge)

Women had recently won the right to vote, and Radiola promised to keep them informed about political candidates: “Politics was no place for ladies, and what little the women knew about it they gleaned from scraps of the men folks’ talk. Radio has changed it all.”

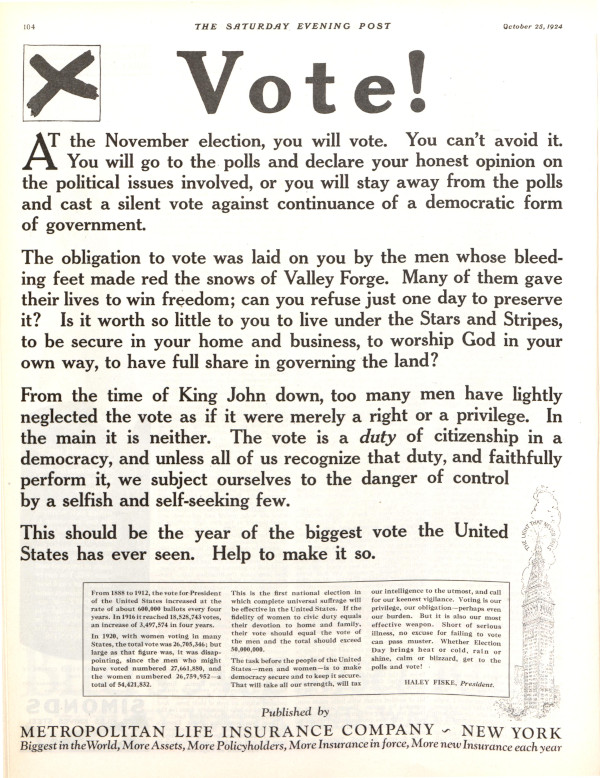

Metropolitan Life Insurance Company

October 25, 1924

(Click to Enlarge)

“The vote is a duty of citizenship in a democracy, and unless all of us recognize that duty, and faithfully perform it, we subject ourselves to the danger of control by a selfish and self-seeking few.”

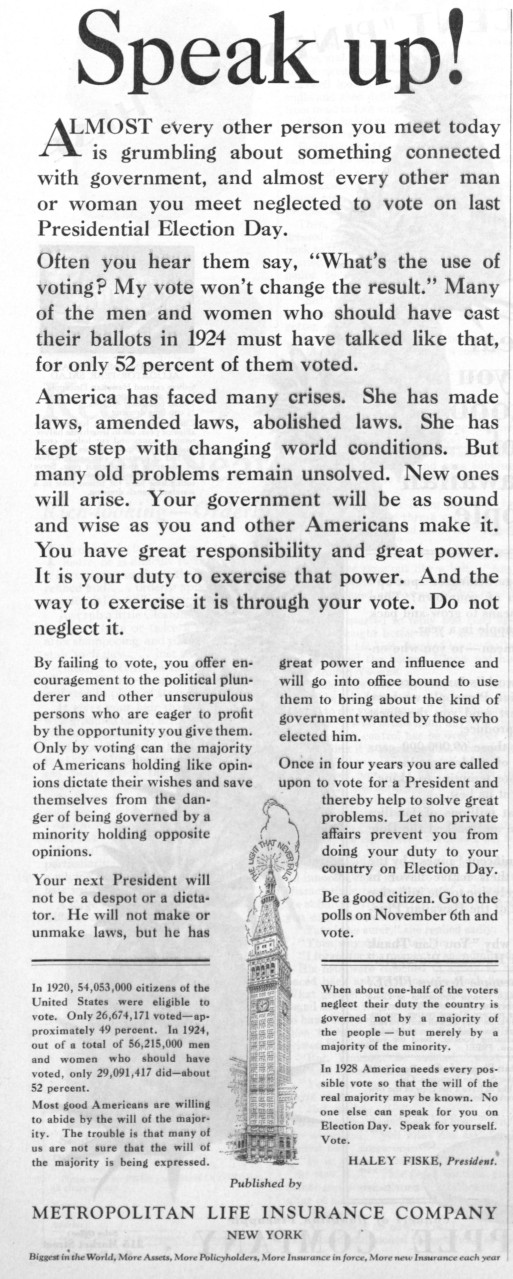

Metropolitan Life Insurance Company

October 27, 1928

“By failing to vote, you offer encouragement to the political plunderer and other unscrupulous persons who are eager to profit by the opportunity you give them.”

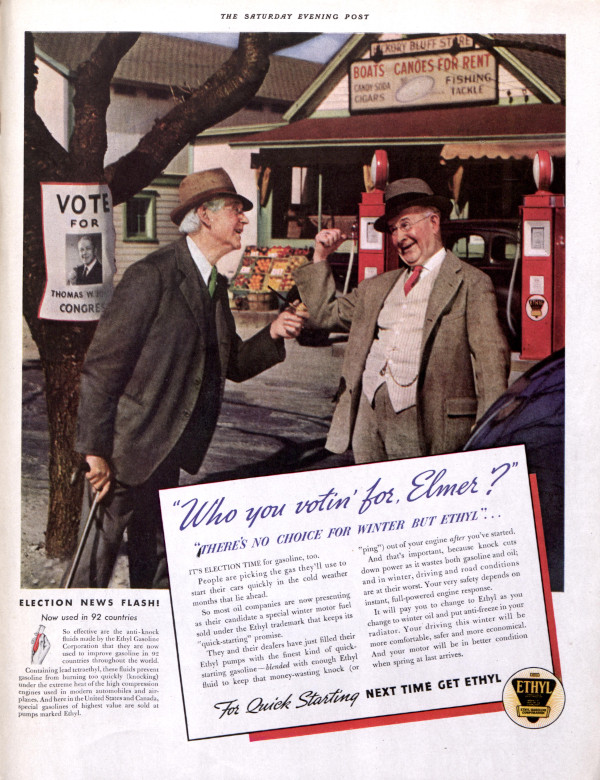

Ethyl Gasoline Corporation

October 31, 1936

(Click to Enlarge)

This ad encouraged consumers to “vote for” Ethyl gasoline to keep the “knock” out of their engines, especially during winter. Ethyl Gasoline Corporation was founded in 1923, a collaboration between GM, Esso, and DuPont to manufacture an additive to make leaded gasoline. Many workers at the plants soon began to suffer from confusion, hallucinations, and even death from lead poisoning. Lead as an additive in gasoline was phased out in the mid-1970s.

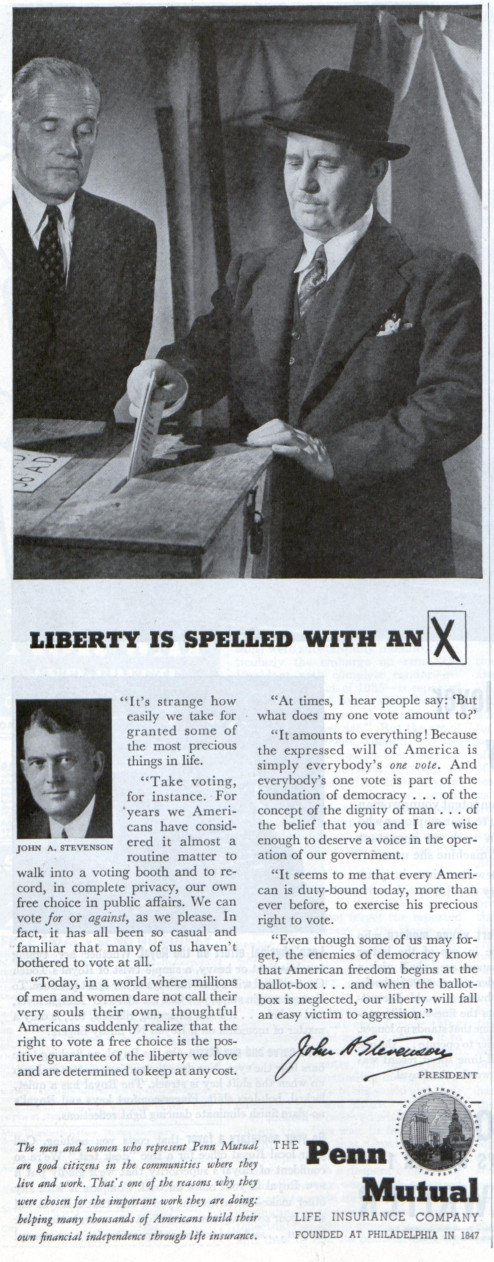

The Penn Mutual Life Insurance Company

November 2, 1940

“Even though some of us may forget, the enemies of democracy know that American freedom begins at the ballot-box . . . and when the ballot-box is neglected, our liberty will fall an easy victim to aggression.”

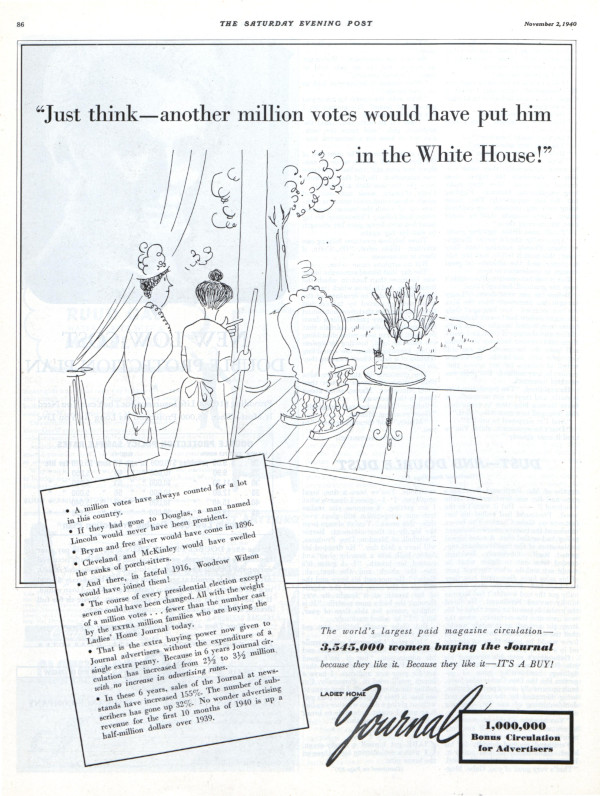

Ladies Home Journal

November 2, 1940

(Click to Enlarge)

The Ladies Home Journal tried to convince prospective advertisers with the rather convoluted argument that because the course of most presidential elections could have been changed with a million votes, the Journal’s million-family increase in circulation should compel them to buy ads.

The Saturday Evening Post

October 31, 1942

(Click to Enlarge)

In the midst of World War II, the Post used a page from its own magazine to encourage people to vote in this mid-term election: “And this year—of all years—let it be a soberly studied vote. A vote for principles—and for the man who will forego considerations of party and political gain in the interests of the national good. A vote for the man in any office, best equipped to face the crucial days ahead—honestly, judiciously, intelligently.”

Rockwell Video Minute: Arguing Politics Over Breakfast

See all of the videos in our Rockwell Video Minute series.

Featured image: Norman Rockwell / SEPS

Cartoons: Election Time

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

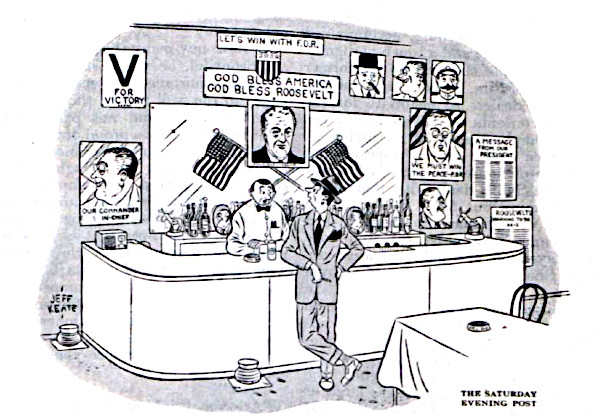

Jeff Keate

October 7, 1944

Bill King

September 13, 1952

Hoff

July 12, 1952

Richter

March 15, 1952

Stan Hunt

December 8, 1951

Clyde Lamb

December 1, 1951

David Pascal

November 5, 1955

Don Tobin

November 4, 1950

Mary Gibson

November 4, 1944

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

In a Word: How We Got to the Polls

Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

All across the country, people will head to the polls without even realizing the repetition (at least historically) in that phrase “head to the polls.”

Middle Low German pol referred to one’s head, but especially the top and back of the head, where the hair grows. This became the Middle English polle (still meaning “head”) around the beginning of the 14th century. So from a historical perspective, “head to the polls” is really “head to the heads.”

Fairly quickly though, synecdoche — the rhetorical device that uses the name of one part of something to refer to the whole thing, like calling your car your “wheels” — took over, and by the mid-14th century, poll was being used to refer to an individual person or animal.

This might bring to mind the idea of taking a headcount; that’s exactly what was happening when shepherds, cowherds, and community organizers took count “by polls”: They were counting heads, one by one.

But people didn’t show up to be counted for no reason. By the 1620s, we find the verb poll meaning not to count heads, but to count votes. And from there, it’s a clear shot to a wider poll-based election vocabulary — including polling place and poll tax — by the 19th century.

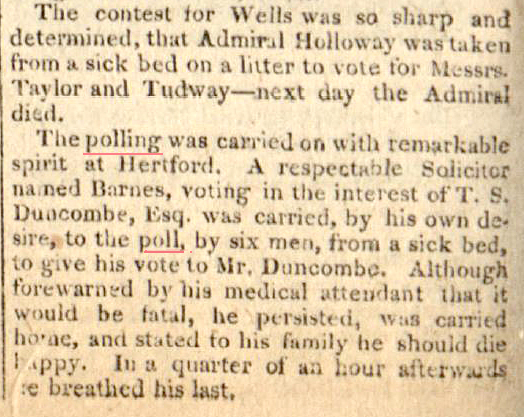

This amazing clip from The Saturday Evening Post of August 19, 1826, finds some men literally dying to vote. In it, we find polling used as a synonym for voting and poll as the place where votes are cast.

The vocabulary that comes into play during elections stems from a wide variety of sometimes surprising etymological sources, some of which I’ve written about before. Check out “What Is a Caucus Anyway?,” “A Candidate as White as Snow,” and “Where Your Ballot Comes From” for a little language trivia you can share with other voters when you poll to the heads — er, head to the polls.

Featured image: Andrey_Popov / Shutterstock

How Much Does Your Vote Weigh?

In 1916, the election was decided by just 3.1 percent of the popular vote.

John F. Kennedy won the presidency by just 0.2 percent.

And in 2000 the presidency was ultimately decided by just 537 votes.

In the next election, you might be among the handful of voters who decides an election.

Theoretically, your vote for the president has the same impact as any of the other 227,000,000 qualified voters in the U.S. And the candidate with the most votes would win.

But the electoral college changes the weight of your vote depending on where you live. And it can give the presidency to the candidate who may have lost the popular vote.

The last time a candidate won popular vote but lost the electoral college vote was 2016, but it wasn’t the only time. It has occurred 5 times before in our history.

When the electoral college was created in 1787, it was originally intended to balance the electoral power so that Americans in sparsely populated areas weren’t outvoted by the people in the cities. At the time, most Americans were living in rural areas; reducing the electoral power of urban voters would have a limited effect.

Today, the urban/rural division in the population is 80/20, but that rural minority has considerable clout in Washington. After the September 11 attacks, for example, Wyoming received seven times as much Homeland-Security money per capita as New York.

Each state has a set number of electoral votes based on its population. With two exceptions — Maine and Nebraska — the candidate who wins the majority of each state’s popular votes is awarded all of the state’s electoral votes. So within your state, your vote has the same weight as any other voter.

But your electoral college impact depends on your state. Wyoming, for instance, with the lowest population (589,000), has three electoral votes. California, with its population of 39,144,818, has 55.

However, the states’ electoral votes aren’t determined by a uniform calculation. Based on 2016’s returns, Wyoming’s electoral votes were drawn from 586,107 residents, or one electoral vote per 195,369 voters. But California’s electoral votes worked out to one electoral vote for 711,723 voters.

You could say that a Wyoming voter had 3.6 times the weight of a California voter.

This is the most extreme example. But if you do the same math to compare the ten most populous and then least populous states, you’ll find their relative electoral weight is a ratio of 1 (most populous) to 2.5 (least populous).

This fact has led to assertions that voters in low-population states have an undue influence in national politics.

But Dale Durran says this isn’t the only distortion of the representative vote. In an article for theconversation.com, the University of Washington mathematics professor found another factor that will affect your vote’s weight.

He divided the total number of America’s electoral votes — 538 — by the 136 million votes cast in 2016 election. The result was the electoral weight of an average vote: one four-millionth of an electoral vote. But this number, as we’ve seen, is altered by the electoral college. And, he finds, it is also altered by the number of ballots cast within a state. Since the electoral votes are fixed for each state, the weight of each ballot diminishes slightly as more ballots are cast.

If you calculate the electoral college weight of each vote with the voter turnout in the state, Wyoming voters still have the greatest weight (2.97), followed the District of Columbia (2.45), and Vermont (2.42). Florida voters had the least weight: 0.78.

Durran illustrates the point with two states — Oklahoma and Oregon — which have the same number of electoral votes. Because fewer Oklahomans cast their ballots (52 percent) than Oregonians (66 percent), an Oklahoma voter had a weight of 1.22 while an Oregon voter has only 0.89.

His analysis shows that your location can raise the weight of your vote, aside from its electoral college value. The impact of these small numbers of votes in battleground states can make a big difference in who gets elected.

Durran identifies five key states where the 2016 race was close. The electoral votes in four of the states —Wisconsin (10 electoral votes), Michigan (16), Pennsylvania (20), and Florida (29) — were decided by just one percent of the votes.

And these were states whose votes had an electoral college weight of less than 0.85. This means, for instance, that fewer than 27,000 Wisconsin voters decided who got their states’ electoral votes.

If you live in one of these states, your vote may not have the same weight in the electoral college as someone from Wyoming or D.C. But Durran’s analysis shows that a relatively small number of people can make a big difference in the outcome of an election.

So if you decide to stay home on election day, you’re not only giving up your vote, but you’re also conferring additional voting power to another voter – one whose interests and values might be at odds with yours. Even if the math shows your vote doesn’t count quite as much as someone’s else, it’s still your country, and your voice, and your chance to make a difference. So vote.

Featured image: hafakot / Shutterstock

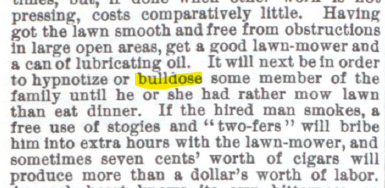

In a Word: The Racist Origins of ‘Bulldozer’

Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

When you see the word bulldozer, you might conjure an image of a large yellow machine with caterpillar treads flattening everything before it with its steel-toothed blade. Or maybe your mind goes back to a smaller Tonka version of this mechanical behemoth that you played with as a child. Taken on its own, with no context, bulldozer might even call to mind some serene bovine scene, perhaps Ferdinand the Bull dozing among the daisies.

How jarring, then, to discover bulldozer’s horrible, violent beginnings.

Bulldozer (originally spelled bulldoser) first appeared in the run-up to the election of 1876. That was the final year of President Ulysses S. Grant’s second term in office, and he had unexpectedly declined to run for a third term. In his place, the Republican party put its support behind Ohio Governor and former U.S. Representative Rutherford B. Hayes, while the Democratic candidate was New York Governor Samuel Tilden.

This was an important election. All the former Confederate states had returned to the Union, post-Civil War Reconstruction was ongoing, and this was the first presidential election in which African-American men could vote for someone who wasn’t Ulysses S. Grant. The outcome of the election of 1876 would shape the future of the South for years to come.

The former slave owners and secessionists in the South knew it, and they weren’t about to sit back and let the North and their former slaves usurp their power and privilege. Despite three new federal laws in 1870 and ’71 designed to protect Black Americans from violence and coercion at the polls, many were bulldosed into silence. Bulldose was a slang term derived from either “a dose fit for a bull” or “a dose of the bull” — the second being a reference to the bullwhip. Bulldosers used physical violence against Black voters either to keep them from the polls or to intimidate them into voting Democratic.

Going into the election, in five states — Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina — a majority of registered voters were African American. One would expect, in a fair election, that the Republican candidate would easily take these states. But after the votes were tallied, Tilden had won the popular vote in Alabama and Mississippi.

The results in the other three states were even more unexpected. After counting had finished, both parties claimed victory in those states. On election night, Tilden was the presumed winner with 184 electoral votes, 19 votes ahead of Hayes and 1 vote away from holding a majority.

The 20 electoral votes of these states (plus Oregon) remained undecided for months as first the two parties and then the two houses of Congress launched separate investigations. Democrats and the Democratic-controlled House committee accused the Republicans of ballot stuffing and coercion. Republicans and the Republican-controlled Senate committee accused the Democrats of the same.

In the end, the presidential election was decided behind closed doors. In what came to be called the Compromise of 1877, the Democrats conceded the remaining electoral votes to the Republicans, making Rutherford Hayes our 19th president, but in return, federal troops were to be removed from the South, essentially ending Reconstruction and returning power to the same men who had controlled the South during the Civil War.

Though violent intimidation at the polls certainly continued, Southern officials found new ways to suppress the Black vote, including Jim Crow laws and grandfather clauses. Bulldosing took on the wider meaning of “to coerce or restrain by use of force,” and it was ripe for a more literal use when large, seemingly unstoppable machines came on the scene.

The machine we think of as a bulldozer was invented in the early 1920s, and by the initial months of the Great Depression, we start to find the term bulldozer in writing, with that Z further obscuring the word’s origins. The violent, racist origin of bulldozer is one reason many people now use the term earth mover to describe these massive machines.

If you’d like to learn more about the election of 1876 — including commentary from the Post while the election results were in flux — read “The Worst Presidential Election in U.S. History.”

Featured image: Andrey Yurlov / Shutterstock

Con Watch: Presidential Election Scams

Steve Weisman is a lawyer, college professor, author, and one of the country’s leading experts in cybersecurity, identity theft, and scams. See Steve’s other Con Watch articles.

The 2020 presidential election is in high gear and has captured the attention of the American public. Of course, anything that the public is interested in becomes an opportunity for scammers to exploit, and the presidential election is no exception. Here are some common election-year scams and how to avoid them.

Robocall Campaign Solicitations

Both former Vice President Joe Biden and President Trump are actively fund raising as we head toward the final days of the campaign. Scammers are making robocalls in which they pose as campaign workers seeking your donations. This particular scam can easily appear legitimate. Caller ID can be tricked through a technique called “spoofing” to make it appear as if the call is coming from a candidate or some political organization, and recordings of the candidate can easily be incorporated into the call to make the call appear more legitimate. Even more significantly, calls from political candidates and other political calls are exempt from the federal Do-Not-Call List, so it is legal for you to get a call from a politician or Political Action Group (PAC) seeking donations even if you are enrolled in the Do-Not-Call List.

How to Avoid this Scam: Whenever you receive a telephone call, you can never be sure as to who is really contacting you, so you should never give personal or financial information to anyone over the phone whom you have not called. If you do wish to contribute to a political campaign, the best way to do this is by going to the candidate’s official website and make your contribution. Scammers can also set up phony websites for the presidential candidates, so make sure that you are going to the candidate’s real website. You can’t trust a Google or other search engines to list the real site first because sophisticated scammers are adept at getting their phony website a high placement in search results. One good way to confirm that a particular website is that of the real candidate or Political Action Committee (PAC) is to use the website whois.com, which will tell you who owns the website you are considering. If it turns out that the website is owned by someone in Russia, it is a pretty good indication that it is a phony website.

Even then, make sure that when you are giving your donation online that the website address begins with https instead of just http. Https indicates that your communication is being encrypted for better security. If you are being asked to contribute to a political organization rather than a candidate, you should definitely do your research to determine the legitimacy of the organization before making a donation. You can check out PACs at the Federal Election Commission or the Center for Responsive Politics.

Email and Text Campaign Solicitation Scams

Political candidates and PACs supporting them may try to contact you through email and text message solicitations, but once again, you can never be sure if the communication is coming from a legitimate source or a scammer.

How to Avoid this Scam: Never click on links in these emails or text messages because the risk of downloading dangerous malware is too great. Instead, if you are inclined to contribute to a particular candidate or PAC, go directly to their website to make your contribution, but again make sure to confirm that you have gone to the real website and not that of a scammer posing as the candidate or PAC.

Registration Scams

Another common election time scam involves a call purportedly from your city or town clerk informing you that you need to re-register or you will be removed from the voting lists. You are then told that you can re-register over the phone merely by providing some personal information, such as your Social Security number. Again, through spoofing, the scammer can manipulate your Caller ID to make the call appear as if it is coming from your city or town clerk.

How to Avoid this Scam: The truth is that your city or town clerk would never call and tell you that you need to re-register. Voter registration is never done by phone. If you have any concerns as to your voter registration status, you can go to your city or town’s website or call your city or town clerk to confirm your status.

Political Poll Scams

Political polls have been a major part of our election process for years. Generally, people are contacted by telephone to answer questions about the candidates and their policies. Because it is so common at this time of year to be called by a political pollster, scammers will pose as pollsters in an effort to trick victims into providing information that can be used for identity theft. Often they will dangle the reward of a gift card or other prize to lure people into participating in the scam poll. Once again spoofing can be used to make the call appear legitimate.

How to Avoid this Scam: Legitimate pollsters do not offer prizes or other compensation for participating in their polls. They also will never ask for personal information such as your Social Security number, credit card number, or banking information. Anyone asking for such information is a scammer and you should hang up immediately.

Featured image: David Carillet / Shutterstock

Considering History: Kamala Harris’s Heritage and the Legacies of Slavery and Sexual Violence

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

In the immediate aftermath of Joe Biden’s selection of Senator Kamala Harris to be his vice presidential running mate, a controversial Newsweek article raised questions of whether Harris, the daughter of two immigrants, would be eligible to serve in that role if elected. The article, authored by a right-wing law professor who had previously run against Harris for the position of California’s Attorney General, doesn’t hold legal water; Harris was born in Oakland and so was, from birth, a United States citizen, as guaranteed by the 14th Amendment. But the article has reignited debates over that Constitutional concept of birthright citizenship, one that President Trump has at various times expressed a desire to do away with.

While Harris’s own citizenship status under that existing law is clear and indisputable (as Newsweek has subsequently admitted), there is another, more genuinely complex part of her heritage and family that has also received renewed attention since the VP announcement. In 2018, Harris’s father Donald, a Jamaican-American immigrant and retired Stanford University economics professor, wrote an article about his Jamaican ancestors in which he argued that he is descended on his father’s side from the infamous 19th century white slave owner Hamilton Brown, who ran one of the island’s largest plantations and was responsible for the importation and enslavement of hundreds of Africans.

Donald Harris’s claims about his relationship to Hamilton Brown have been used by conservative pundits like Dinesh D’Souza and others as a “gotcha” moment, as the basis for arguments that neither Harris nor her supporters can discuss the legacies of slavery and racism since she herself is descended from a white slave owner. But in truth that heritage, which is shared by a significant number of Americans of African descent, reflects one of the most essential and too-often forgotten histories of slavery and the sexual violence that accompanied it. And if we set aside political and partisan concerns, Harris’s story can help us understand those vital histories of slavery, sexual violence, race, and heritage, the legacies of which are certainly still with us in 21st century America.

One of the most consistent and central elements of chattel slavery, as it was practiced throughout the Americas, was the rape of enslaved women by male slave owners. It is difficult if not impossible to ascertain the percentage of enslaved women who were so violated (and thus of enslaved children who were the product of such acts), both because the practice was so ubiquitous and because it was for centuries under-narrated in histories of slavery. The latter trend has been challenged in recent years, as illustrated by historian Rachel Feinstein’s When Rape Was Legal: The Untold History of Sexual Violence During Slavery (2019) among other works.

Another recent trend that has made it more possible to grapple with these histories is the rise of ancestry studies and the corresponding use of DNA analysis to trace heritages. For example, the scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr., a pioneer in the use of such data to analyze individual, familial, and collective ancestries, estimates that “a whopping 35 percent of all African-American men descend from a white male ancestor who fathered a mulatto child sometime in the slavery era, most probably from rape or coerced sexuality.” And since that number reflects 21st century identities and all the other factors that have contributed to them, it likely only scratches the surface of how widespread these practices and their effects were in the era of slavery.

While many of those experiences are unfortunately lost to history, individual case studies can help us engage with the aftermath of sexual violence under slavery. As I highlighted in this July 4th column, the story of Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings offers one particularly prominent such case study. After nearly two centuries of rumors and debate, both DNA analysis and the pioneering work of scholar Annette Gordon-Reed have confirmed that Jefferson did rape and father at least one child (and almost certainly six or more children) with Hemings, one of the enslaved women on his Monticello plantation. Historians have only begun to uncover the complex stories of the descendants of those sexual assaults, enslaved young men and women who, despite their famous father and the promise of freedom that came with that status, still experienced some of the worst of antebellum American slavery and racism.

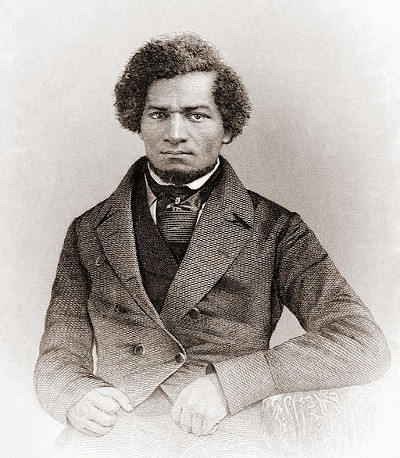

Another of the 19th century’s most famous Americans, Frederick Douglass, experienced life as the child of sexual assault under slavery. In the opening chapter of his 1845 Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Douglass notes his belief that his father, whom he never knew, was the white slave owner of the Maryland plantation onto which he was born. As usual with his autoethnographic works, Douglass uses this personal detail to illuminate social and historical meanings, noting for example that the law making the children of enslaved women themselves slaves “is done too obviously to administer to [slaveowners’] own lusts, and make a gratification of their wicked desires profitable as well as pleasurable; for by this cunning arrangement, the slaveholder, in cases not a few, sustains to his slaves the double relation of master and father.” But Douglass also empathetically notes the potentially painful effects for all involved, from masters having to sell their own children to “one white son” having to “ply the gory lash to his [brother’s] naked back.”

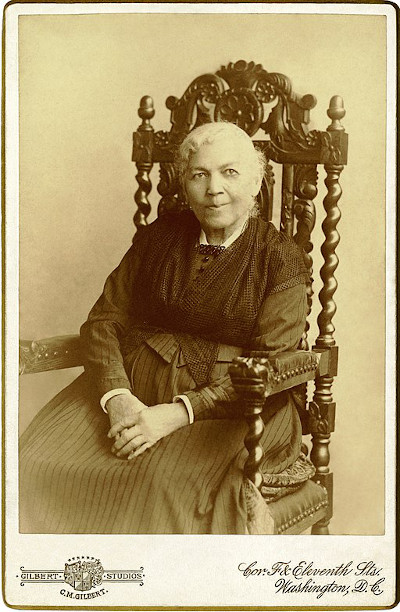

Douglass did not have the chance to know his mother well before her tragic death, so he was unable to write about her perspective. But another prominent personal narrative of slavery, Harriet Jacobs’ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861), captures the experience of enslaved women under the constant threat of sexual violence. As Jacobs puts it in her chapter “The Trials of Girlhood,” “there is no shadow of law to protect her from insult, from violence, or even from death; all these are inflicted by fiends who bear the shape of men…She will become prematurely knowing in evil things. Soon she will learn to tremble when she hears her master’s footfall. She will be compelled to realize that she is no longer a child.” And through her own constant battles with her despicable master Dr. Flint, Jacobs traces how “the influences of slavery had the same effect on me that they had on other young girls; they had made me prematurely knowing, concerning the evil ways of the world.”

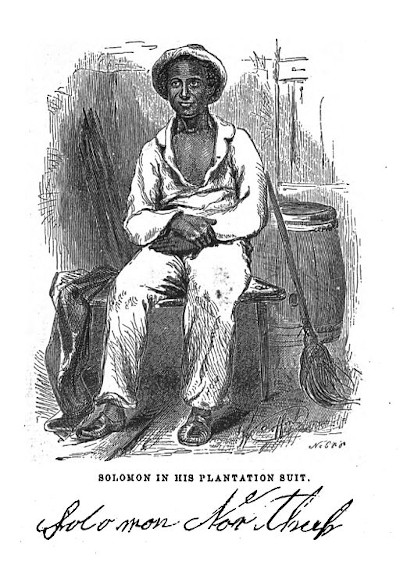

Individuals like Douglass and Jacobs managed to escape the horrors of slavery and publish their stories. But of course the vast majority of both enslaved women raped by their owners and the children of those rapes remained enslaved throughout their lives. We get a glimpse of such experiences in another personal narrative, Solomon Northrup’s Twelve Years a Slave (1853). At the final plantation to which Northrup is taken, he meets Patsey, an enslaved young woman whose beauty and strong will make her a singular focus of her owner Edwin Epps. If not enslaved, Northrup writes, Patsey “would have been chief among ten thousand of her people”; but on the Epps plantation, this impressive young woman becomes instead “the enslaved victim of lust and hate,” with “no comfort in her life.” Although the illegally kidnapped Northup is eventually rescued from the Epps plantation, he can do nothing for Patsey; a tragic reality captured in a culminating scene from the 2012 film adaptation of 12 Years, as Northup (Chiwetel Ejiofor) watches Patsey (Lupita Nyong’o) recede as he rides away from the plantation.

No one can blame Northup in this moment, as there is nothing he can do for Patsey. But for far too long, both our laws and our collective memories likewise abandoned enslaved women like Patsey and their children to sexual violence and its effects. We cannot change the past, but—with heritages like Kamala Harris’s to help guide us—we can remember those histories and consider all that they mean for all Americans.

Featured image: Kim Wilson / Shutterstock