Everything We Thought We Knew About Salt and Health Was Right

Unlike sugar and trans fats, we might accept salt in our food as a human necessity, an ancient mineral that conveniently boosts flavors in bland fare.

But we’ve been fed a line about sodium chloride. That’s what Dr. Michael F. Jacobson claims in his new book Salt Wars: The Battle Over the Biggest Killer in the American Diet.

For decades, Jacobson has worked with the Center for Science in the Public Interest — a group he helped found — to advocate for tighter health regulations on American food, writing a heap of books along the way advising on the science behind nutrition.

It might seem as though scientists just can’t make up their minds about the health effects of a salt-heavy diet, but Jacobson says the conflicting messages are a mix of junk science and industry deception. He argues that science has long confirmed that we consume too much salt, leading to unnecessarily high rates of cardiovascular disease, and his book tracks the half-century-long fight between “Big Salt” and health advocates — like himself — seeking to reduce the stuff in our food. Jacobson says it’s finally time to cut the salt in our food by one-third and act on the facts we’ve known all along.

The Saturday Evening Post: How do you defend the science you put forth in your book? Is there a scientific consensus that sodium consumption is too high?

Michael F. Jacobson: There has long been a consensus that we should reduce sodium intake to reduce the risk of heart attacks and strokes. The consensus is reflected in statements from organizations like the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the World Health Organization, and the American Heart Association. These are not organizations that take risky positions or base their statements on flimsy evidence. Typically, in fact, they wait far too long to tell the public to do one thing or another.

In contrast, the “opposing side” — if you want to put it that way — has a comparative handful of studies that have been criticized for basic flaws from the day they were published. At this point, I hope that the debate over salt has ended. Last year the National Academy of Sciences issued a report that summarily dismissed those contrarian studies as being basically flawed. They dismissed them with a sentence, citing the other evidence that has long been mainstream.

SEP: You write about the “J-shaped curve” — the finding that lower salt intake also results in a high risk of cardiovascular disease — as the basis of a lot of these “contrarian” theories around salt. What do you make of the science behind it?

Jacobson: It’s junk. The PURE studies [Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology], which have been the most widely publicized as showing that consuming less salt could be harmful, are based on taking one urine sample from a number of participants at the beginning of the study. One sample. It’s not even a 24-hour collection, which is the standard for measuring sodium intake. The next assumption they make is that one sample is representative of a person’s lifetime consumption, but it’s not. Maybe that person ate out that day, or maybe they had cancer and were barely eating. People have long criticized that research, but in the last few years two studies completely debunked it.

Last year, the NAS did a report on sodium and cardiovascular disease. They did a meta-analysis of the best studies that involve 24-hour urine collections and found the expected linear relationship. They dismissed the PURE studies and others that found the J-shaped curve, as fatally flawed. I hope that ends the controversy.

A few years ago, Congress said the government shouldn’t take action to reduce sodium until the NAS did a study to look at sodium’s direct relationship to cardiovascular disease. Well, now they have done that study, concluding that lowering sodium is beneficial and not harmful.

SEP: How would you say that news media figures into the controversy around diet science like this?

Jacobson: I don’t understand why health journalists have given unwarranted credence to the PURE studies and their predecessors, because they’re so contrary to what the bulk of the research says. I think they, starting with The Washington Post and The New York Times, have been really irresponsible. Maybe it is an example of “man bites dog” to some extent. I bet editors love those stories that publicize the contrarian view, especially when the researchers are at respected institutions.

In the case of the PURE studies, they’re not tainted with industry funding. Rhetorically, it’s easier to shoot down studies that are funded by the snack food industry or something. But I’m really puzzled, and many other people in the field of hypertension and cardiovascular disease are shocked that those [PURE] researchers continue to get funding for that kind of research, and that respected publishers — like the Lancet or British Medical Journal — accept these studies. They certainly confuse the public.

The same phenomenon has taken place on a whole range of public health issues of great importance. With the lead industry — defending lead in gasoline — it goes back 100 years. Typically, it’s industry either sponsoring the research, or, if the research is independent, then ballyhooing the research that supports their views, saying, now government can’t act until we do studies that may be impossible to do.

With salt, there’s been a “moving of the goalposts.” Thirty years ago, the evidence was clear that increasing sodium intake increased blood pressure, and increased blood pressure then increased the risk of cardiovascular disease. Almost every researcher agreed then that raising salt increased the risk of cardiovascular disease, but after a couple of studies contrarians said that those conclusions couldn’t be coupled, that we had to prove directly, with randomized controlled studies, that raising sodium increases the risk of cardiovascular disease. Those studies are almost impossible to do. A few studies (I mention them in Salt Wars) provide some evidence, but they’re all limited in one way or another. But the American Heart Association and the WHO and others say that that research is totally unnecessary, they are certainly not funding the research, and we have far more evidence than we need to call for policies to reduce salt in the food supply and diet.

The thrust of the bulk of the field is to say, let’s reduce sodium throughout the food supply to “make the healthy choice the easy choice.” There are studies showing that if you start with lower-sodium foods and add salt, you’ll generally end up with less salt than what we see in most of our foods now.

SEP: You’ve been involved in health advocacy for many decades. What have you seen change in industry and policy as far as the American diet is concerned?

Jacobson: With salt, the policy battles began in 1969 when the White House Conference on Food, Nutrition, and Health said that sodium in the food supply should be lowered. At that time, and currently, the Food and Drug Administration considers salt to be “generally recognized as safe,” and could be used in any amount. But on the basis of the existing research back in 1978, we [Center for Science in the Public Interest] petitioned the FDA to adopt regulations to lower sodium, and top researchers supported the petitions.

A few years later, the FDA in the Reagan administration was headed by a hypertension expert, and he said that we should lower sodium by taking a voluntary approach and that if industry didn’t lower sodium, he would mandate it. That commissioner left the agency after two years, and meanwhile industry did next to nothing. Then, CSPI focused on getting sodium labeling on all foods, and we helped get the nutrition labeling law passed, which mandated labeling like the Nutrition Facts labels that list sodium on all packaged foods. So we waited to see whether labeling would reduce sodium intakes, and when I looked at it 10 years later I saw that, no, it didn’t seem to have any effect. Sodium consumption stayed the same. So in 2005 we re-sued the FDA and filed a new petition. By then, the evidence was far greater that sodium boosted blood pressure. But the government did nothing. So we then succeeded in getting Congress to fund the NAS to do a study on how to lower sodium intakes.

In 2010, the NAS published a landmark report saying the FDA should mandate lower sodium levels in the food supply, but the FDA commissioner immediately said they would push again for voluntary reductions. It took a while — six years in fact — for the FDA to come up with voluntary targets for lowering sodium in packaged foods. That was in June 2016, just months before the Obama administration left office, so clearly there was not enough time to finalize those targets.

Four years later, the Trump administration still has done nothing. Absolutely nothing. Although, two years ago, the FDA commissioner Scott Gottlieb — who’s been in the news about COVID-19 — said that reducing sodium is probably the single most important thing the FDA could do in the nutrition world. Unfortunately, he left office a few months later and the FDA did nothing.

It’s been 10 and a half years since the NAS called for mandatory reductions in sodium, and the last time that the CDC looked, in 2016, there had been no change in sodium intake in 30 years. At this point, I think the most we can hope for is the implementation of those voluntary targets. The FDA chose targets that would lower sodium to recommended levels — if all food manufacturers complied, which they won’t — in 10 years. In 10 years, a lot of people are going to be dying unnecessarily.

SEP: What was the Salt Institute? Would you characterize it in the same way that people think of the tobacco lobby or the oil lobby?

Jacobson: Steven Colbert said that the Salt Institute shouldn’t be confused with the Salk Institute, because the Salk Institute cures polio while the Salt Institute cures hams. That got a laugh from the audience [when Jacobson was a guest on Comedy Central’s The Colbert Report in 2010]. The Salt Institute was long a lobbying group set up by salt manufacturers, like Morton Salt and Cargill.

In the book I call it “the mouse that roared.” It was a small organization — five or six staff members and an annual budget of about three million dollars — but they were real tigers when it came to defending salt. Any time people criticized sodium levels in the food supply and recommended changes, the Salt Institute would be out there with vitriolic statements, pamphlets, interviews. They generated a large amount of press that I think contributed significantly to muddying the waters. They made much of that J-shaped curve theory, that reducing sodium dramatically could actually increase the risk of heart disease. But in March of 2019, they abruptly went out of business, and no one, to my knowledge has explained why.

SEP: Since the Salt Institute has disbanded, do you see an opening for salt regulation?

Jacobson: Well, the Salt Institute was never the real powerhouse. The major player was the mainstream food industry, including Kellogg’s, General Mills, McDonald’s — all the big companies, through their trade associations, and especially the Grocery Manufacturers Association. The industry kind of begrudgingly went along with voluntary reduction, but when the FDA proposed action, they nitpicked almost every single number in the FDA’s proposal. The butter and cheese industries wanted their products entirely dropped from the plan. Surprisingly, at the beginning of 2020, the Grocery Manufacturers changed its name [to Consumer Brands Association], changed its focus away from nutrition labeling and nutrition issues in general. The two main lobbying groups essentially withdrew from the playing field.

That certainly should make it easier for the government to take stronger action on sodium. But will it? I don’t know. Many of those big companies will lobby on their own. The snack food industry has SNAC, frozen food companies have the Frozen Food Institute, pickle makers have Pickle Packers International, restaurants are defended by the National Restaurant Association, and the meat industry has the North American Meat Institute. It’s hard to know how the disappearance of those two groups will affect things but making progress won’t be a cakewalk.

Between voluntary and mandatory approaches, the voluntary approach rewards companies that don’t do anything. I talked to one official at Kraft Foods, and he said that Kraft has tried to reduce sodium, but its competitors didn’t, so Kraft felt it had to go back and restore the salt. The advantage of mandatory regulation is that it provides a level playing field for companies that want to do the right thing.

SEP: Looking at the whole scope of the last 50 years or so, what would you say makes it so difficult for the U.S. to make and pass policy regarding dietary health?

Jacobson: It’s the power of industry. But also, much of the public sees a smaller role for government compared to countries in Europe, for example. Here, we have a culture of “rugged individualism.” There’s a feeling that people can lower their sodium intake if they want, a much more voluntary, individual approach.

In contrast, the British government, in the mid-2000s, adopted recommendations to lower sodium and backed that up with a pretty aggressive public education campaign. Then they used the bully pulpit to press industry to lower sodium. Within five years, the UK achieved a 10 to 15 percent reduction in sodium intake, compared to a goal of 33 percent reduction. But after a change in government, the new government lost interest.

Chile, Mexico, Israel, and a couple of other countries have passed laws requiring warning notices on packaging when foods are high in calories, saturated fat, sodium, or sugar. These are put on front labels and are very noticeable. In Chile, the law has been in place long enough to measure some results. There have been a significant number of products that have lower sodium, sugar, or fat content to escape those warning labels. That has been the most effective policy I know of to lower the sodium content in foods and presumably to lower sodium intake.

SEP: Have we seen better health outcomes in Chile as well?

Jacobson: It’s too early to know. Something like cardiovascular disease takes so long to show up. There are also so many other things going on in Chile that come into play.

SEP: Do we see sodium affecting communities differently in the U.S.? For instance, African-American communities?

Jacobson: African Americans seem to be more salt-sensitive than whites. They also have higher rates of hypertension. African-American women have much higher rates of obesity. So, when you couple obesity with hypertension, that’s a formula for cardiovascular disease. But every subgroup of the population ends up with hypertension. By the time Americans are in their 70s and older, 80 to 90 percent have hypertension. That’s why people should lower their sodium intake, lose weight, and avoid too much alcohol, to avoid gradually increasing blood pressure.

SEP: What would a lower sodium diet look like for a lot of people?

Jacobson: Packaged foods and restaurant foods would be lower in sodium. At restaurants, portions would even be smaller. There would be little effect on taste. Let me remind you that no one is saying that industry should eliminate all salt. Rather, it’s lowering salt as much as possible without destroying the taste of the food, and maybe replacing some of the salt with flavorful ingredients.

Using less salt is the cheapest, easiest thing to do. Another way is to replace salt with potassium salt. It doesn’t taste as salty, but it helps counteract the blood pressure-raising effect of a high-sodium diet. Companies can also add more real ingredients and herbs and spices. For home chefs, McCormick, Chef Paul Prudhomme, and Mrs. Dash sell salt-free seasonings. The classic study is the DASH-sodium study. It’s a randomized controlled study — the best you can do — done by researchers at Harvard, Johns Hopkins, and elsewhere. They lowered sodium by one third, from 3,400 mg, the current average daily intake, to 2,300 mg, the recommended intake, and they found that people consuming the 2,300-mg level of sodium liked the food even more than the higher level! So, I think concerns about taste are completely overblown. People quickly get accustomed to less-salty foods.

SEP: What are some personal decisions that people can make to decrease their sodium intake?

Jacobson: Sodium levels in the food supply will not drop to healthy levels instantly, no matter what the FDA does. In the meantime, consumers have to protect their health. When you’re eating processed foods, you should compare labels, because there is wide variation among different brands of the same or similar foods. Swiss cheese has one-fifth or less of the sodium in American cheese, and you can make a perfectly good sandwich with Swiss cheese. For that sandwich, you can also choose a lower-sodium bread. Bread, because we consume so much of it, turns out to be one of the major sources of sodium. You can make lots of modest changes to achieve major reductions in sodium.

We should also be cooking more natural ingredients from scratch. That invariably results in lower-sodium foods, because we’re controlling the salt. The third thing is to eat out less often. Restaurant foods have huge amounts of sodium, especially table-service restaurants like IHOP or Chili’s. That’s partly because the portions are enormous. The more food you eat, the more sodium you consume. From a chef’s point of view, the two magical ingredients are salt and butter. And it’s not just chain restaurants. Chefs have generally not been trained to lower sodium. The best thing you could do is to cook at home from scratch using lower-sodium recipes.

I mentioned how some companies are using potassium salt, and consumers can use it too. Look for “lite salt” at the supermarket. Morton and other companies sell this, and half of the table salt has been replaced by potassium salt, so you automatically cut back when you’re cooking or sprinkle it on your meal.

SEP: Looking back at the last year of presidential debates, moderators always ask a question about the biggest issue facing Americans, and I’ve never heard a candidate say that it’s salt. So, what would you say to people who think we have bigger problems and salt just isn’t that important?

Jacobson: We do have other pressing problems. Tobacco is killing a lot more people than salt. But high-sodium diets are killing tens of thousands of people each year. Health economists and epidemiologists estimate that if we can cut our sodium intake by one-third to one-half, that would prevent 50,000 to 100,000 premature deaths every year. We’re seeing the same thing around the world, where high-sodium diets are causing more than one million deaths a year. I see salty diets as the cause of a pandemic.

We have to deal with COVID-19, that’s the immediate pandemic. High-sodium diets are harmful over a longer time frame. But our society really needs to take these problems seriously even though the deaths are not immediately linked to the cause. An airplane crash kills 300 people and that gets a lot of attention, and it should. But with public health crises, where deaths are less easily associated with the cause, solving the problem is easily postponed, especially when industry stands to gain by not solving the problem. High-salt diets are absolutely something that political leaders need to address.

Featured image: © 2020 The MIT Press, Photo by Chris Kleponis

Getting Good Habits Back on Track During COVID-19

Many of us dropped our resolve during the COVID-19 outbreak. Stuck inside, isolated from friends and family, we ate too much, drank too much, “forgot” to exercise, and let many other good habits slide. What will it take to shed a few pounds, restart your fitness routine, and drop your newly acquired bad habits? Here are tips for getting back on track from clinical psychologist Vaile Wright, Ph.D., of the American Psychological Association:

- Reflect on past victories. Build resolve by recalling ways that you overcame difficult situations in the past. Drawing on those experiences can serve you well in an uncertain future.

- Write it down. Make a list of personal goals and five things that motivate you to achieve each one. Put the list where you will see it.

- Take baby steps. Don’t try to return to your former fitness level overnight, for example. Instead, start small. Focus on exercising

a little the first week. Start working on diet changes the week after. - Overcome resistance. Feel that you’ve lost your motivation? Sleep in workout clothes and, in the morning, roll out of bed and go for a walk. Or join up with a workout buddy or walking partner — a tried and true motivation tactic.

- Deny temptation. This tip is so obvious, it shouldn’t need to be stated, but it’s incredibly effective: Keep trigger foods and drinks out of the house. Toss out the candy; give away that extra case of beer. Then, set rules around when and where to eat and drink.

- Acknowledge the problem. Make a note of the ways that your worries lead you into bad habits, and craft coping skills to help ease anxiety. Hobbies like knitting, baking, or assembling jigsaw puzzles are pleasurable and help regulate runaway emotions.

- Get help if you need it. Seemingly minor bad habits can get worse. It’s absolutely time to see a trained mental health provider when we are unable to care for ourselves because of anxiety, depression, and substance abuse. “We, as humans, are resilient and adaptable. While these adverse times will likely have long-lasting effects, life on the other side can be good: having closer personal relationships, having a better sense of what’s important to you and the world, finding some meaning in what you do. I do think that’s all possible,” adds the expert.

This is adapted from an article featured in the July/August 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock

America’s School Nursing Crisis Came at the Worst Time

On a recent episode of the podcast RN-Mentor, Robin Cogan gave a less-conspicuous perspective on the current push for schools across the country to return to in-person learning: that of a school nurse. “When I look at opening schools,” she said, “and I’ve been very entrenched in it both at the state level and at the local level — it feels to me like we’re doing the biggest social experiment ever without an IRB [institutional review board] … our hypothesis: we are going to have kids and staff that are sick and, God forbid, die.”

Cogan, a Nationally Certified School Nurse from New Jersey, writes the blog Relentless School Nurse, where she’s been sharing useful information as well as stories from school nurses around the country. One has been tasked with providing their own personal protective equipment. Another spoke out against her school’s reopening plan in Georgia and resigned from her position. Cogan’s recent posts have revolved around a central theme: “It Has Taken a Pandemic to Understand the Importance of School Nurses.”

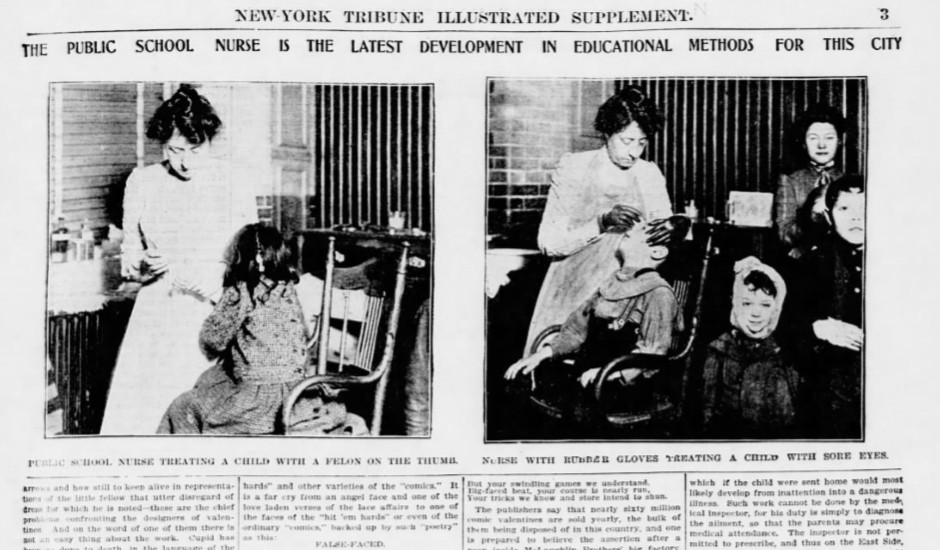

Around a century ago, school districts around the country were just coming to realize the value of adding a nurse to their ranks. In newspapers from Sacramento to Bloomington, Illinois to Washington, D.C., stories applauded school boards for often-unanimous decisions to budget for school nurses.

In 1918, The Charlotte News reproduced an entire paper read by a Miss Stella Tylski at a P.T.A. meeting: “There can be little doubt, that as the work of the nurse becomes better understood, there will be a greater demand all over the world for her services in the schools, for wherever she has made her entry, her value has been recognized.”

At some point in the last 100 years, however, school nurses fell off the list of public school priorities. In recent decades, many school districts have been eliminating qualified school nurse positions. According to a 2017 study from the National Association of School Nurses, less than 40 percent of schools employ a full-time nurse. In the western U.S., it’s only 9.6 percent. Twenty-five percent of American schools don’t even have part-time nurses.

As health considerations have taken center stage in conversations around education, it’s difficult to imagine a responsible plan for returning to school during a deadly pandemic that doesn’t include an on-site medical professional. Yet, for many of the country’s strapped schools, that may seem to be the only option.

Since its inception, school nursing has been predicated on public health.

School nursing in the U.S. began as a sort of experiment. At the turn of the century, when cities were becoming crowded with unsanitary slums that beckoned reform, public schools faced attendance problems stemming from influenza, tuberculosis, and skin conditions like eczema and scabies.

Although the New York Board of Health performed routine medical inspections of the city’s schools — and sent home children with troubling symptoms — there wasn’t a system in place to ensure students would recover properly. In 1902, The Henry Street Settlement, founded and led by nurse Lillian Wald, pioneered a program to place one nurse in four city schools — with around 10,000 students total — for one month.

The nurse was Lina Rogers, and her undertaking was a significant one. She was to perform her nursing duties at each school with makeshift facilities. At one school, she had only a janitorial closet as an office and an old highchair and radiator as examining furniture. At another, she treated students on the playground. “When children found out that they could have treatment daily and remain in school,” she wrote, “‘sore spots’ seemed to crop up over night.” Perhaps most importantly, Rogers made visits to students’ homes to discuss their ailments and treatment with their parents. She found it difficult, but necessary, to demonstrate medical care and explain the importance of hygiene in preventing illness.

At the end of the Henry Street Settlement’s month-long experiment, Rogers was appointed to lead a team of school nurses in the city. The month before she started in schools, the city saw more than 10,000 absences in a month. One year later, the number of absences for the month was 1,101.

Rogers became a chief advocate for school nursing, and cities across the country noted the Henry Street Settlement’s success. In 1908, The Spokane Press, among many others, applauded the New York school nurses for improving their city’s school attendance and “converting the truant into a studious pupil.”

Rogers wrote a textbook in 1917 detailing her work and giving guidance to the nation’s women who were setting out on this new occupation. She found the presence of health professionals in schools to be a vital aspect of public education’s mission to prepare American children for happy and healthy lives, but she recognized the tall order of staking the health of a community on one position. As she visited students’ homes, she found that things other than illness were keeping them from school, such as babysitting, housework, street crime, and neglect. “So the field of vision of the school nurse rapidly widened,” she wrote. “It was easy to see that if the school children were to be given even a fair opportunity of preparation for life’s work and duties, many things in the social life of the homes had to be improved. All the social problems of humanity, problems as old as the world, face the school nurse at the threshold of her work.”

Throughout the postwar years and the Great Society programs of the 1960s, school health programs were expanded to address drug abuse, students with disabilities, and mental health, among other public health inequities. School nurses became iconic fixtures of American schools, tasked with identifying and treating rising chronic illnesses.

But after the recession of 2008, school funding took a hit. Most states cut funding to education, and much of those losses have yet to be fully recovered. Since school nursing programs rely on school budgets — and few states mandate them — they’ve been quietly eliminated, consolidated, or replaced by untrained employees for years. Less than one-third of private schools employ any kind of school nurse at all.

American school nurses still find themselves advocating for public health amid dire circumstances. Most of them are paid less than 51,000 dollars per year, and the prospects of career mobility in the field are stark. A University of Pennsylvania study found that 46 percent of school nurses were dissatisfied with their opportunities for advancement. During the COVID-19 pandemic, however, nurses could be among the most important figures at any school.

In a phone call, the president of the National Association of School Nurses, Laurie Combe, mentioned that the first swine flu outbreak was discovered by a school nurse in 2009: Mary Pappas of Queens, New York. “We have expertise in collaborating with health departments to identify, record, and manage communicable diseases in schools,” she said. “We’re the public health practitioners closest to communities on a daily basis.”

According to Combe, nurses are a vital position in any school. She says they have, in many cases, already been working with schools on emergency operations planning. Throughout this pandemic, school nurses have informed their schools on the safe dissemination of food — to families who rely on free and reduced lunches — and technology and educational materials. They’ve continued to make sure students have access to their health providers and medications, as well.

“When schools don’t have the public health and infection control expertise of school nurses, they’re at risk of mismanaging the proper procedures. They risk mixing well children with those who might be symptomatic of COVID-19,” Combe says. “We know that when school teachers have to direct their time to managing health conditions, there is a loss of instructional time, principals lose administrative time. If students are unnecessarily dismissed, parents may lose wages. There is a cross-sector loss of time and money when there is not a school nurse present.”

Combe says the precautions that schools need to put in place in order to reopen during the pandemic are costly, like facility improvement, personnel, and PPE. The NASN is calling on the federal government to direct 208 billion dollars to support schools’ needs. “If schools are essential to reopen the economy,” she says, “then schools need the same financial support as businesses.”

The question of when it is safe for schools to reopen has different answers for different parts of the country, since schools are experiencing the burden of the virus at varying degrees. Cogan writes, “The bare minimum that we need to safely reopen schools is a stable, low rate of COVID-19 in the community [about 5 percent]; funding for and availability of basic public health precautions … and access to testing for students and school staff.”

In the midst of the most drastic public health crisis of our time, the forgotten heroes of our schools may prove to be an imperative component to our national recovery. If it did “take a pandemic to understand the importance of school nurses,” then perhaps that national lesson will endure this time around.

Featured image: American National Red Cross photograph collection (Library of Congress), July 1921

Ask the Vet: Safer Chew Toys

Question: Baxter, my 5-year-old retriever mix, broke a tooth while gnawing on a bone, and the vet said his enamel was badly worn, probably from chewing on tennis balls. Can you suggest safer chew toys?

Answer: The nylon fuzz on tennis balls damages enamel in two ways: It’s abrasive even when clean, and it picks up dirt that acts like sandpaper on teeth. The lesson: Anything harder than teeth breaks teeth. The list includes natural and nylon bones, dried pig ears, hard plastic chew toys, and even ice cubes. Safe chew toys, the rubber kind, have some “give.” (Kong black toys are good for power chewers.) Offer Baxter a twisted rope toy and some dental chews. Also, increase his physical activity to tire him out before he settles down for a chew.

Ask the Vet is written by veterinarian Lee Pickett, VMD. Send questions to [email protected] and read more at saturdayeveningpost.com/ask-the-vet.

This article is featured in the July/August 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Photology1971 / Shutterstock

In a Word: Splitting Migraine

Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

We’ve all felt the pain of a headache at least once in our lives. I’m thankful, though, that I‘ve never had to suffer through the agony of a migraine, which, I learned this week, usually starts on one side of the head and then spreads until your whole noggin is throbbing.

When ancient Greek physicians started treating patients with migraines, they latched on to that symptom of starting in only half the head and called it hemikrania; that’s the hemi- meaning half (as in hemisphere) plus krania, from the Greek word for skull, kranion. The word entered Late Latin as hemicrania, the second part formed from what is the more well-known medical term for the skull, cranium.

Old French took up this half-a-skull headache word as migraigne or migraine. But where did that first syllable go? The transition makes sense if you know a little French. For most French words that begin with an H — like hôtel, hôpital, Hermès scarves — the H is not pronounced. If hemicrania is said with a silent H, the first syllable of the word now just sounds like “eh,” the nonlexical sound one might make while trying to think of the next thing to say. It wouldn’t take long for that first syllable to be reinterpreted as not part of the word and dropped completely. (In linguistics, this type of word evolution is called metanalysis, and it’s more common than you might think.)

The word was adopted into Middle English around 1400 with a variety of spellings, but over time, two prominent variants emerged. The first is the migraine we know today, which is usually restricted to naming those horrible headaches. But the second spelling, megrim, found multiple, figurative meanings in the language, including the headache, an earache, an unwanted disturbing thought, and general low spirits. Megrims even appeared in this last meaning in James Joyce’s Ulysses, the 1922 novel that has been known to cause headaches in students.

Featured image: Shutterstock

The Problem with the Mindfulness Movement

You leave work late and drive home in rush-hour traffic, listening to a podcast with a climate scientist explaining the gloom-and-doom scenario that awaits us all. When the traffic jam finally breaks up, you get your economy car up to speed, and — Bam! — you hit the pothole you’ve been avoiding for months, piercing a tire. When you finally make it back to the small apartment you pay too much money for, you check your mail to find a bill from your recent hospital visit just shy of your $2,000 deductible. You close yourself into a quiet room and open the Aura app on your smart phone that guides you through a focused breathing meditation to cultivate mindfulness.

Is it working?

Mindfulness, a practice taken from Buddhism, has steadily popularized as a remedy for daily stresses over the last few decades. Big CEOs, therapists, and scientists have testified for the “life-changing” results of looking inward, but some thought leaders say it’s only part of a wider trend of individualizing societal problems.

When I first spoke to Dr. Ronald Purser, he read my puzzled mind, saying “You’re probably thinking I seem awfully anti-capitalist for a management professor.” Purser, a professor of Management at the College of Business at San Francisco State University, is also an ordained Zen Dharma teacher in the Korean Zen Taego Order. He has been publishing papers on management and organizational change through Buddhist or ecological lenses for decades. His most recent book, McMindfulness, is a critique of the rising industry around the practice of mindfulness and its corporate proponents: elites cherry-picking Buddhism to offer cold comfort and reinforce individualism.

The Saturday Evening Post: What is the mindfulness movement?

Purser: It’s not a monolith, but I think, in general, we’ve seen how a therapeutic modality gradually morphed into a capitalist spiritually, as I put it. Mindfulness as a therapeutic intervention started with Jon Kabat-Zinn’s work in 1979. It initially offered an alternative intervention for chronic stress and other maladies, but for many years it was confined to hospitals and clinics. Around 2000 to 2005, it became mainstream. This whole process involved slowly growing scientific interest around mindfulness to garner legitimacy. To offer mindfulness as a medical intervention, it really had to be mystified. What I mean by that, is that the explicit connection of mindfulness practice to any kind of Buddhist sources had to be downplayed. Once it was decontextualized from a Buddhist framework — like teachings on ethics and morality, and so forth — it could gain traction in secular audiences, and then entrepreneurship kicked in.

I think it gained a lot of traction after the financial crisis of 2008 because people were overwhelmed by the stresses and anxieties they were facing. Mindfulness offered a convenient respite, a way to turn away from all of the structural and political challenges of our time.

Post: What’s wrong with people practicing mindfulness? Isn’t it a healthy habit?

Purser: There isn’t anything inherently wrong with using mindfulness to de-stress. The problem isn’t that using mindfulness for stress-reduction doesn’t work — the problem is that it does work! But work in the service of whom and for whose interests? For example, just as there is nothing wrong with treating those suffering from depression, the problem is when the diagnosis and dominant narrative is that depression is nothing but a chemical imbalance in the brain. The pharmaceutical industry has a huge financial stake in maintaining and propagating such a narrative that is based on biological reductionism.

Similarly, the mindfulness industry and its proponents have a vested interest in maintaining a narrow way of framing and explaining stress in our society, which also adheres to a reductionist focus on the individual. Whether explicitly or implicitly, it sends the wrong message that the stresses people experience are just inside their own heads, or that their external resources and social conditions don’t matter. People may find that they could be a lot less stressed if they organized around collective resources — by building community, and engaging more politically in solidarity with others in changing our political and economic systems. It’s not an either/or choice, but the mindfulness apologists have chosen the individual to the downplaying of the social and communal dimensions of mindfulness.

This is partly because mindfulness has been embedded in therapeutic culture. This is what the late critical psychologist David Smail called “magic voluntarism:” de-contextualized individuals alone are held responsible for their stress and anguish, regardless of the social and economic milieu in which their lives are embedded. And mindfulness is now a DIY technique that an isolated individual can perform in order to cope with the challenges of modernity.

Post: Is mindfulness related to positive psychology?

Purser: These self-help techniques, to me, all represent a way of rekindling individualism in our society. The neoliberal ethos is alive and well, so these methodologies don’t meet any resistance when it comes to integrating them into our culture. One of the latest fads is “grit” or “resilience,” it’s this notion that all of our success and happiness are just a matter of turning inward and finding our inner resources. They all subscribe to the idea of the autonomous individual, which is separate from the community. It’s a sort of hyper-individualistic way of legitimizing neoliberalism.

Post: Would you say we are experiencing more stress in the current time period than times past? I’m thinking particularly of the turn of the last century and the many accounts of widespread stress in this country as people moved into cities in large numbers, among the many other societal changes.

Purser: In the book, I chronicle the long history of how we got to the discourse of stress that we’re using now. At the turn of the century, there was that strange diagnosis called neurasthenia which was a bizarre diagnosis reserved primarily for upper classes. It was actually a badge of honor. They saw it as the price you had to pay for progress and industrialization. But, certainly, they were going through something. The diagnosis at the time was different than it is now, but I think there’s a parallel there. In both cases, you see the medical community coming in and overlaying the etiology, basically saying that it’s located in the individual.

But I think that we are more stressed. There are statistics on this. Workplace stress is on the rise, as are stress-related diseases. A World Health Organization study that found around $300 billion a year is lost due to stress at work. Part of my critique is that the cure places the burden of responsibility on individuals.

Post: You’re in San Francisco. What can you say about the practice of mindfulness in Silicon Valley?

Purser: It’s huge. It really took off probably around 2010. Google became a sort of poster child for corporate mindfulness with the publication of Search Inside Yourself by Chade-Meng Tan, a Google engineer. Big conferences, like Wisdom 2.0, are held every year here in San Franscisco. It’s very popular in the Valley, which has always had this kind of spiritual, libertarian character to it. Steve Jobs had a background in Zen. But it’s selectively appropriated to optimize worker engagement. They’ll say it’s a form of “brain hacking.” In the 1960s, LSD was used for consciousness expansion, but now it’s used — via “microdosing” — to become more productive. Similarly, Zen was very anti-establishment and anti-materialistic, and now it’s used as a productivity enhancement tool for corporations.

By focusing only on individual-level stress reduction, these programs don’t take into account the systemic and structural problems in the workplace that are causing the epidemic of stress in the first place. In other words, there is no critical diagnosis of workplace stressors, which are long hours, work/family conflicts, economic insecurity, and lack of health insurance. Paulo Freire, author of Pedagogy of the Oppressed, called these “aspirin practices” because they promise to make the world a better place, but they really don’t change the root causes of stress that people are feeling.

Things like mindfulness seem very benign on the surface, so it’s almost incredulous to call them into question. But the harm is more at the socio-political level, because you’re basically letting corporations off the hook for responsibility of the social pollution they’re dumping on people. It’s not a form of brainwashing, or some conspiratorial thing, but what it does do is deflect attention away from collective ways of organizing to affect structural change.

Post: Do you see any signs of a movement that addresses your criticisms of this kind of individualistic mindfulness?

Purser: There are a lot of people on the fringes thinking about this besides me. I think we’re at a point where we have to come to terms with the idea that focusing on individual psychology and individual-based interventions are just not going to do it anymore. If you look at the ecological crisis, it’s a spiritual crisis. We’re dealing with suffering on such a systemic level that just retreating into our caves is problematic. I understand the need to cope, but the form of suffering that we’re dealing with is institutionalized and collective, not just at the individual level.

I think things can turn very suddenly and unexpectedly. If I were a practitioner of mindfulness in Australia right now, I think I may start considering other approaches. We have a hard time imagining other possibilities because we’ve been subject to this imagination machine of neoliberalism for so long that it’s hard for us to consider alternatives. We might want to turn to a more creative engagement with our own prophetic traditions — like the Judeo-Christian tradition — which account for social justice and oppression. A fundamental teaching in Buddhism is interdependence with all beings and with nature. I think that part of the equation hasn’t been given enough attention.

Purser’s book, McMindfulness, was published in 2019 by Repeater Books. Purser also recommends The Mindful Elite: Mobilizing from the Inside Out by Jaime Kucinskas.

Featured image by Repeater Books

The Role of Dreams in Human Survival

The contents of our dreams have been the subject of study and speculation for as long as humans have slept all over the earth. In Homer’s Iliad, a dream is personified as a messenger sent from Zeus to tell Agamemnon to attack the city of Troy. Shakespeare mused on the possibility of dreams in the afterlife: “in that sleep of death what dreams may come when we have shuffled off this mortal coil, must give us pause.” Freud’s best guess was that our dreams are full of metaphors for penises.

Since dreaming is such a universal human experience, we’ve long figured these nightly hallucinations must have some sort of meaning or utility. The serious study of dreams, or oneirology, is a relatively new field that offers new insights each year for why we dream. Phallic symbols seem to have little to do with it, but some new research is pointing toward our own survival as a reason for dreaming.

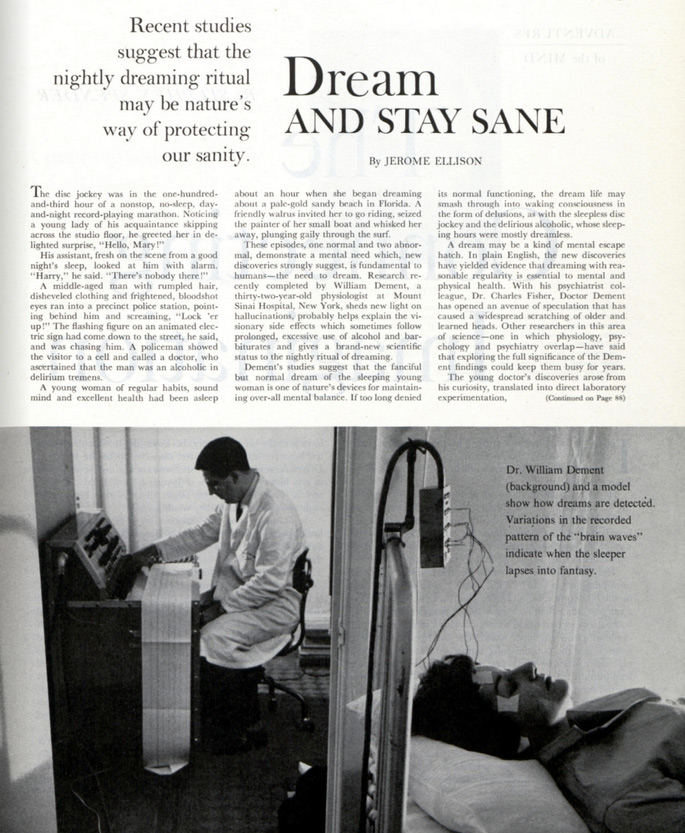

The beginning of the scientific study of dreams can be pinned to the discovery of REM (Rapid Eye Movement) cycles by Nathaniel Kleitman and Eugene Aserinsky in the early 1950s. The Saturday Evening Post focused on the findings of their colleague, William Dement, in a 1961 article called “Dream and Stay Sane.” Dement’s studies asked the important question of “whether a substantial amount of dreaming is in some way a necessary and vital part of our existence.” Dement and his colleagues theorized that the hallucinatory nature of dreams gave the mind a sort of recess each night that could protect it from insanity during the day.

Dr. Joseph De Koninck, emeritus professor of psychology at University of Ottawa, has been studying dreams for much of his career, and he says we’ve come a long way since those early days. While the distinction between the necessity of dreaming and the necessity of REM sleep still remains unclear, studies have since observed dreaming — although it is less common and typically less vivid — in non-REM sleep. A particularly impactful discovery, De Koninck says, was the realization that the frontal lobe is at rest during dreams while other parts of the brain like the amygdala are active. Because the frontal lobe is responsible for functions like judgment and mathematics and the amygdala houses emotions — especially fear — this explains why we find it difficult to plan or think critically in dreams yet experience emotions like joy and fear in abundance.

Those bouts of ecstasy and terror in our sleeping hours could be serving specific functions.

De Koninck was involved in one study, published last year in Consciousness and Cognition, that tested part of a theory of why we have bad dreams, the Threat Simulation Theory. The TST posits that “the function of the virtual reality of dreams is to produce a simulation of threatening events, the sources of which are derived from situations experienced while awake and associated with a strong negative emotional charge.”

The TST was developed in 2000 by Finnish cognitive neuroscientist Antti Revonsuo to give a biological explanation for nightmares. He proposed that our ancestors’ brains adapted to simulate real-life threats in our dreams so that we would be prepared to cope with such dangers in waking life. The 2018 study shows that threat simulation in dreams is more active in traumatized individuals and can even be activated by threatening events and high stress levels in a day preceding a dream.

The theory that our dreams might exist to simulate real-world events as a purposeful function accounts for more than the nightmares. The Social Simulation Theory (SST) is a similar psychological model that looks at social interactions in dreams, from the friendly to the aggressive to the sexual. If dangerous situations in dreams exist to prepare us for such threats in the world, then perhaps the many social encounters we dream up could be adaptive measures to aid our interactions as social beings.

De Koninck points to “Social contents in dreams: An empirical test of the Social Simulation Theory,” forthcoming in Consciousness and Cognition, as the latest example of this sort of research. Previous studies — going as far back as the ’60s — have found that real-world isolation can actually increase the amount of social content in dreams. The 2019 study confirms this, showing the social contents of dreams to be greater than those in concurrent waking life in its participants. It did not back up another tenet of the SST, however, that “dreams selectively choos[e] emotionally close persons as training partners for positive interactions.” In this study, participants’ dream characters were more random than had been observed in past studies.

When I spoke with De Koninck, I shared with him a dream I experienced the previous night that contained both a social and a threatening scenario. In it, I arrived in Juneau, Alaska to attend a distant acquaintance’s wedding and bumped into Dame Judi Dench. We each smoked a cigarette and she expressed her annoyance at the tourists surrounding us. I was too starstruck to say much. Later on, I was in a convenience store when an armed robbery took place. As the assailant approached me, gun drawn, I reached into a cooler and grabbed a can of soda before cowering on the ground.

Did I fail the simulation? I don’t even drink soda.

Perhaps, but the important thing, according to De Koninck and others, like author Alice Robb, is that I actively shared my dream. As inconsequential and boring as they can seem, dreams have proven to be helpful when shared or recorded. In a 1996 experiment, women who were going through divorces experienced positive self-esteem and insight changes after taking part in dream interpretation groups. De Koninck says “Dreams can be a source of self-knowledge that have adaptive value. Keeping a dream journal or sharing your dreams can help you to know yourself better or better adapt to situations.” But this doesn’t mean you should panic over a particularly weird or violent dream. He refers to dreaming as an “open season for the mind,” and says we should approach any interpretation open-mindedly instead of with some sort of a universal method.

What if you believe you don’t dream or — more likely — cannot remember your dreams? You are not necessarily maladaptive if you can’t remember your dreams, but there are ways to improve your dream recall. One is to simply think about dreams and dreaming more when you go to sleep and wake up (this could explain why I remembered so vividly my Alaskan romp with Judi Dench), and try to remember as much as possible when you first arise. Another is to vary the time you wake up. Since most of our dreaming happens in REM sleep, we are more likely to remember a dream if we wake during a REM cycle.

Whether our dreams are nightly firings of random artifacts of the brain or the products of important psychological evolution, they will never fail to terrify and bemuse us. In a brief time, we’ve come to embrace the “open season of the mind” and glean more from it than we could have thought possible. The future of dream research, a field that relies on new technology and mounding data, is promising.

Featured image: Ford Madox Brown: Parisina’s Sleep—Study for Head of Parisina (Wikimedia Commons)

George H.W. Bush: Post Archives Reveal a Handyman of Politics

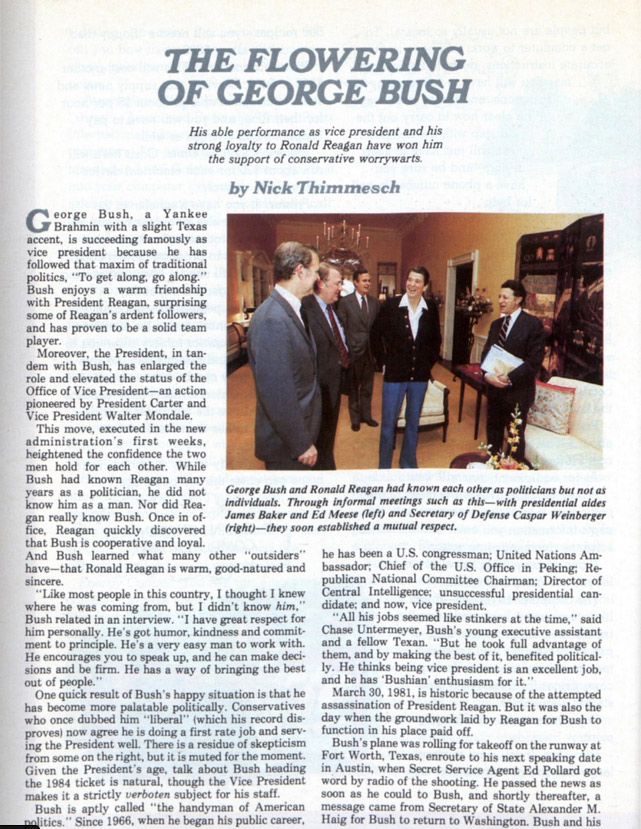

George H.W. Bush will be remembered most for his Presidential term, but the New England-born aristocrat served in many capacities of federal government before becoming the chief executive.

In “The Flowering of George Bush,” the Post covered his rise in a Republican party that was previously reluctant to trust the statesman for his perceived liberal tendencies. He had served as a House representative, U.N. Ambassador, Chief of the U.S. Office in Peking, Republican National Committee Chairman, Director of the C.I.A., and Vice President. “‘All his jobs seemed like stinkers at the time,’ said Chase Untermeyer, Bush’s young executive assistant and a fellow Texan. ‘But he took full advantage of them, and by making the best of it, benefited politically. He thinks being vice president is an excellent job, and he has ‘Bushian’ enthusiasm for it.’”

During the attempted assassination of Reagan in March 1981, Bush demonstrated his loyalty to the President as well as his willingness to rise to whatever the occasion called of him: “Everything went smoothly because the President had laid the groundwork,” Bush said. “It was a judgmental call for me on some occasions. I didn’t want to make it appear as though I was making presidential decisions, although I did have a substantial role.” Bush’s Vice Presidency continued in a larger scope, similarly to Walter Mondale’s before him.

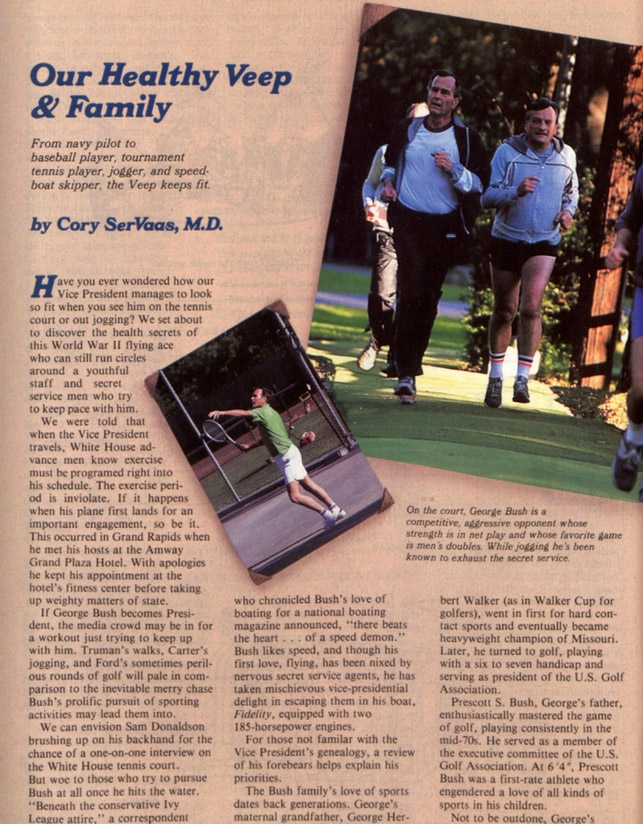

Years later, in 1988, Bush’s health habits were the focus of a feature, “Our Healthy Veep & Family,” by Saturday Evening Post Publisher Cory SerVaas, An avid golfer, runner, baseballer, and tennis player, the Veep was about to win his election when this magazine detailed the exercise habits of Bush Sr. Despite his busy campaign schedule, exercise was non-negotiable for the future President: “The exercise period is inviolate. If it happens when his plane first lands for an important engagement, so be it.” The article also featured a candid interview with his wife, Barbara. Mrs. Bush extoled her husband’s virtues and shared why she wanted to marry him: “I figured anyone who was as nice to his little sister as this young man was would surely make a fine father for our future children.”

Become a subscriber to gain access to all of the issues of The Saturday Evening Post dating back to 1821.