Wit’s End: Get Ready for the Worst. Summer. Ever.

Like a mole emerging, blinking, into the sunlight, the nation is poking its snout into the air, and there is cautious talk of some non-home activities resuming.

But make no mistake: This summer is going to be one of the lamer ones on record. Gone are the carefree days of doing whatever the hell you feel like in July and the barely-remembered schoolyard retort: “You’re not the boss of me.” This year, the local July 4th fireworks extravaganza has been cancelled, and your federal, state, and county government is very much the boss of you. A year ago, acting responsibly meant trying not to hit anyone with your car, but by this summer, 6,000 new rules will govern that slice of American life called “leaving the house.”

Major buzzkills in the summer of 2020 may include:

Shopping. Does your niece have an upcoming birthday? Eager to browse the latest nonfiction releases? Bathroom faucet leaking and you need a . . . thingy from the hardware store? STAY IN YOUR CAR, MAGGOT. Don’t even think about physically entering a shop. “2019 called: They want their sense of entitlement back!” It’s 2020, and here’s the rules: If you phone in advance, specifying the exact item you want and your debit card number, a store employee grateful to have a job at all will text you when it’s available for curbside pickup. Please wear a mask and do not breathe on said employee. Sneezing will result in your immediate arrest. Thanks, come again!

Summer camps. All children’s summer and day camps are cancelled. The public pools are closed, so hopefully you have a rich friend with a pool. (Don’t try to befriend people with swimming pools in 2020. It’s too late, you presumptuous peasant.) Any child trying to climb a public play structure in the summer of 2020 will be hosed down by city workers with a mixture of lye and tap water. Public libraries will remain open between the hours of 1:00 and 2:30 p.m. on Tuesdays, allowing up to ten masked children inside at one time. Once in the library, each child will be relegated to an individual Caring Square, a six-by-six-foot area of carpet, because caring for other people means staying away from them, you grubby little vectors. Now scamper back home to your parents, who are beginning to get the hang of heavy day-drinking.

Travel. Cancelled. Persons attempting to cross state lines in the summer of 2020 will be chased back to their abodes by a masked mob brandishing sticks. In the absence of law enforcement, the mob is authorized to take corrective action against citizens attempting a chill road trip to Sedona or Moab. Anyone on a beach is a de facto “beach bum” subject to a loitering citation. From June through August, you’ll stay in your backyard and like it, you human murder hornet.

Family reunions. If your clan insists on getting together this summer, at least have the decency to exclude Grandma. She’s better off confined to her home, a locked-down nursing facility, or a wise old tree that embodies her spirit as in the movie Pocahontas. While the family matriarch shelters in place, relatives can enjoy her ghostly presence with brand-new Holo-Gram technology, enabling 3-D apparitions of Holo-Gramma, Holo-Grampa, and Holo-Old Lady at Church Back When Church was a Thing. Just don’t try sitting on Holo-Gramma’s lap, kids: She’s nothing but light particles in air!

Nights on the town. Remember when “dinner and a movie” was a cliché? Though not very adventurous, it’s what most people did for fun. This summer, though, conversations may go like this:

“I’m planning to bungee-jump off a rock cliff into an 800-foot gorge out of sheer existential boredom.”

“Yeah, I get that. I really do. Good luck!”

“And if I survive, I’m thinking of going out for dinner and a movie.”

“What? Seriously? Have you thought this through?”

“I just miss being around people, you know? And the new Christopher Nolan film will be in theaters in July —”

“Theaters? I wouldn’t be caught dead in a public movie theater. Do they even take your temperature before you enter?”

“No, I don’t think so. But they’re seating people several feet apart —”

“Wow, I guess I had no idea you were so selfish. What if you’re an asymptomatic carrier and strangers die because you’re ‘tired’ of watching feature films at home? ‘Oh, takeout’s not good enough for me! I’m the King! I get whatever I want, watch me bang my scepter and make bad choices that benefit only myself! Bang! Bang!’ Just wow.”

Personal Grooming. With all the waxing salons closed, plan on seeing a lot of hairy legs, back fur, and other unpleasantness this summer. Look for the 1920’s unisex swimsuit to make a comeback: short, one-piece overalls that cover everything from the neck to mid-thigh. It will be for the best.

Going into June, 2020 continues to be a rough year, but there are things even a national shutdown can’t take away. Long, sunny days, burgeoning gardens, and having our immediate family members around 24/7, literally every second of our lives, are some of the things we can look forward to, as well as hiding in the garage per usual.

And don’t forget to run some medical experiments for the greater good. Germany is kicking butt on the global pandemic scorecard, possibly because beer has anti-viral properties. We will be testing that theory at home this summer. Results to follow.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Wit’s End: Stuck at Home? There’s a Meme for That

Weeks ago, when everyone in my office started working remotely, we began sharing funny memes to keep in touch.

The thinking was that, as lockdown orders swept the nation and anxieties mounted, if a colleague still had the presence of mind to send an amusing, work-appropriate meme, they could probably be trusted with other things.

If, on the other hand, someone “went dark” and texted nothing to the group, or sent a blurry photo of a crying face, or a series of beer emojis, or the phrase “I can’t even,” it was a sign to subtly direct the workflow elsewhere.

Swapping visual jokes about shared experiences – toilet paper shortages, Zoom meetings, children cooped up at home all day – has been good for group morale when we’re miles apart. But a decade ago, few of us would have known what a meme was.

Richard Dawkins, an evolutionary biologist, coined the word “meme” in his 1976 book The Selfish Gene. Just as a gene transmits genetic information, a meme transmits cultural information. Examples of memes were “tunes, ideas, or catch-phrases” that “[leapt] from brain to brain,” wrote Dawkins. A decade later, writer Eloise L. Kinney described memes as “simply put, ideas that catch on.”

In 2020, when people say “meme,” they usually mean a joke, fad, or image that’s circulating on the Internet. According to a source in my household, today’s fifth graders traffic heavily in memes, sharing cat jokes on social media and learning dance moves from TikTok videos.

“The dance that’s trending all over America,” my 11-year-old daughter informed me, “is called The Renegade, where you just fling your arms around meaninglessly.”

That’s a meme.

Now that the nation’s office workers are stuck at home, many of us have seized on memes as a popular art form. Years from now, novels will be written, movies filmed, and music composed about this period in history, but no one can wait for these thoughtful, intricate forms of expression. We need to see our bizarre predicament mirrored back to us, right now, in the form of a doctored photo of Julie Andrews’ Maria from “The Sound of Music” being dragged away from the Bavarian Alps by police officers, with the tagline: “The Hills are closed.”

Indeed, they are. The clever mash-up of a classic reference and a current problem is what makes some memes so appealing. They’re free to all and have a universal feel. In our celebrity-obsessed culture, meme-makers ply their craft in anonymity: Everything that made me laugh today was conceived and executed by some faceless nerd, playing a dangerous game with the law of copyright.

During the last several weeks, we’ve seen “Brady Bunch” memes and memes of Jack Nicholson in “The Shining,” dressed in a bathrobe and leering insanely with a drink in his hand. (The joke was that his character, Jack, seemed to be coping pretty well with isolation.)

We’ve shared memes of dogs hiding after the umpteenth daily walk, and obese cats sprawled on the couch, embodying our “weekend plans.”

There have been “Star Wars” memes (Obi-Wan attempting to remote-teach Luke Skywalker about The Force), and memes based on old sitcoms like “The Office” and “The Golden Girls.”

Then there are random, semi-disturbing images, like the meme I found of a goose with human arms, gesticulating wildly. The tagline quoted the 1985 Aretha Franklin radio hit: “Who’s Zoomin’ Who?”

“Do you do any actual work?” asked my husband at some point.

“Yes! We get a lot done. These funny memes are helping us stay motivated!”

He shrugged and shuffled back to the bedroom where his work laptop was, along with the pretzels, chips, and salsa he now ate in there. We had relaxed the household rules, everyone coping in their own ways. My new shutdown habits were sending memes and taking naps, which suddenly seemed like a pleasant way to live. Why hadn’t we been doing these things all along?

Of course, most things about the national situation weren’t funny. Like everyone else, we were concerned for the sick and elderly, people whose jobs put them at risk, and the millions now out of work. We were helpless to solve these big problems, however, and succumbing to worry and depression would help exactly no one. So it seemed okay – even necessary, perhaps – to find things funny. If America lost its creative, irreverent sense of humor, the terrorist had won.

Hence, The Atlantic’s recent essay: “Yes, Make Coronavirus Jokes.” Writer Tom McTague observed that “as the world hunkers down, . . . there’s been a mass outpouring of gags, memes, funny videos, and general silliness. We might be scared, but we seem determined to carry on laughing.” Shared humor creates feelings of bondedness, acceptance, and community, McTague reported. “If we’re all finding this experience of being forced to stay home funny, it’s reassuring, a form of collective therapy.”

Similarly, Esquire published an essay earlier this month called: “Coronavirus Memes Brought My Dad and I Closer Together.” Sheltering in place far from his aging parents, writer James Stout praised silly memes (like “high-quality clips of people falling over”) for connecting him and his father in laughter on a daily basis. “Maybe it’s a bit of a stretch to think that dogs driving lawnmowers will bring us all together after this is over, but it is genuinely heartwarming to see the internet being used to spread joy,” he wrote.

Now if you’ll excuse me, I’m off to Google “cutting own hair bad idea memes 2020.”

Featured image: Shutterstock

Wit’s End: 10 Ways to Keep the Spark Alive While Sheltering in Place

With many American families temporarily confined to their homes, couples are suddenly spending more time together than ever before. As nerves fray and relationships are tested, here are a few modest suggestions to keep your pandemic romantic.

1. Spend time on your appearance, even though you never leave the house. This crisis may seem like the time to stop wearing undereye concealer or see if you can grow a beard down to your waist. Resist those urges. If you live with another person — or even a sensitive plant, like an orchid — strive to look reasonably attractive, causing your partner to think, “Wow! I’m pretty lucky.” Not, “This disgusting slob is using all my precious toilet paper.”

2. Check in with each other often. Between working remotely, homeschooling, and watching the news, it’s easy to forget to ask your spouse, “So, what have you been up to in the 20 minutes since we saw each other?” The answer may surprise you — “I’ve been curled in a fetal position under my weighted blanket” or “I found an expired can of chili, so I ate it, out of the can” — and bring you closer.

3. Don’t overshare. Though you could announce every random thought to your domestic co-prisoner, this is not recommended. When asked a question, aim for the breezy summary, not the Russian novel.

Compare: “How am I? I . . . I feel like the walls are closing in. The children’s voices are like nails on a chalkboard. I’m experiencing a strange compulsion to drop the cat out of a second-story window to see if it lands on its feet. What, we don’t have a cat? The dog then. Any animal, really.”

With: “Pretty good. You?”

4. Break the rules once in a while. Tap into your inner Rebel Couple, like the outlaws Bonnie and Clyde, and sneak out of the house on a non-urgent day trip. Park the car in an abandoned street and sit in it together, taking in the view. If a police car drives by, duck down in your seats: What you’re doing is now illegal in eight states! Enjoy the frisson of being “bad,” but do not get out of your car. (Seriously, please don’t.) Now drive home again.

5. Serve your spouse a romantic dinner in the privacy of your walk-in closet while the kids watch Frozen 2. Then do whatever comes naturally, like (finally) tidying up the closet. After 1 hour and 43 minutes in there, the house will seem much bigger than before.

6. Renew your wedding vows after updating them for 2020. In a ceremony broadcast to family and friends via Skype, hold hands in the living room and intone:

“I, Brad, promise to honor and cherish you, Melissa, without ever leaving our home because you will not let me go buy groceries, claiming I don’t ‘do it right.’ Please, Melissa, I need to get out of here once in a while. I’m a human being.”

“I, Melissa, promise to stand by you, Brad, in sickness and in health, even if I’m half in the bag because I’ve been drinking wine all day out of sheer boredom. Can you go to Safeway and get more wine? Never mind, I’ll do it.”

7. Cuddle up on the couch and watch movies together. It’s the perfect shelter-in-place date. What could go wrong? Just make sure your film choices aren’t subtly passive-aggressive, like House of Flying Daggers, Unforgiven, and 10 Things I Hate About You.

8. Allow one spouse to move into the basement, where he can work remotely, read books, eat, and sleep without disruption. The remaining spouse can pretend her husband is away on a business trip when she is visited by a rugged stranger like Clint Eastwood, who woos her while photographing the bridges of Madison County. After their torrid affair, the mysterious stranger rambles out of town, i.e., returns to the basement for the next five to seven days. Repeat.

9. Read the bestselling self-help book, Mating in Captivity. Published in 2009 by therapist Esther Perel, this popular book offered a metaphor for the challenge of long-term monogamy. Now revised to account for actual captivity.

10. Try to remember the big picture. Though it feels like you will be stuck at home forever, this too shall pass. And when it does, you may even miss it a little. Oh, you won’t miss your spouse’s insane competitiveness at board games or the loud sounds they make while chewing, but it may make you sad to hear, “I can’t open that pickle jar for you / sew on a button / make you a sandwich / give you a backrub / take the kids outside for twenty minutes. I’d like to help, but I’m back at the office, remember?”

Featured image: Shutterstock

Wit’s End: They’ve Turned the Soundtrack of My Youth into Muzak

Read more from Maya Sinha’s column, Wit’s End.

I was in a department store, shopping for items the Victorians called “unmentionables,” when a 1992 song from the British band The Cure began to play.

From hidden speakers, under the bright retail lights, lead vocalist Robert Smith — a pale Goth in eyeliner, lipstick, and a tangle of ink-black hair — sang the opening bars of “Friday I’m in Love.”

This song was deeply familiar from my high school and college years. Back then, Smith was a romantic figure: a moody, sensitive rebel who fronted an alt-rock band. Though he strove to look three-quarters dead, he would not be caught dead in the women’s underwear section of the flagship store in a suburban mall.

Yet here he was in 2020. A wave of cognitive dissonance crashed over me. Why was the store piping in The Cure, a poignant reminder of my vanished youth? Was nothing sacred?

For Americans born between 1965 and 1980, the generation known as Gen X, this is now a common experience while shopping. We select lettuce from a superstore crisper to the rapturous vocals of Belinda Carlisle in “Heaven Is a Place on Earth” (1987). We try on sensible shoes to the late Dolores O’Riordan of the Cranberries singing “Linger” (1993). Checking our tween into the orthodontist’s office, we’re assailed with INXS’s darkly urgent “Devil Inside” (1987) or REO Speedwagon’s earnest “Keep On Loving You” (1980). We gas up our SUVs to the sound of giddy infatuation in Sting’s “Every Little Thing She Does is Magic” (1981).

Decades later, these 1980s and 1990s pop songs still pack a wallop. In a recent essay, Gen X writer Meghan Daum wrote that she’s stopped listening to four decades of pop music, songs that evoke so many bittersweet memories that she now avoids them “as if avoiding pain.”

These one-time radio hits are powerfully evocative, Daum writes, because music “embeds itself into our emotions, often burrowing far deeper than the memories of the events that spurred those emotions. From there, the songs we love become the half-life of our emotions. They are whatever’s left of whatever was going on at the time.”

For people in their 40s and 50s, pop songs conjure memories of childhood, junior high, high school, summers, friends, significant others, college, jobs, holidays, weddings, divorces, and family events. Just little things like that. No biggie.

But if you’re trying to avoid the pain (or mixed feelings) these songs evoke, too bad: The hits of 1980-1999 are playing on continuous loop at the grocery store, a cavernous building you disconsolately roam four times a week. Good luck buying organic peanut butter without crying, Mom! Have fun picking out dog food while tears of regret and forever-lost chances burn your eyes!

The cruel irony of listening to bouncy pop songs from junior year while tossing headache medicine and nutritional supplements called Change-O-Life into the shopping cart is apparently lost on the corporate overlords who devised this torture. Why have they done this, desecrating our memories by canning our music?

Piping music into public spaces was the brainchild of U.S. Army Major General George O. Squier, a renowned inventor who devised a means of playing phonograph records over electric power lines. In 1934, after radio took off, Squier founded the Muzak Corporation, which piped commercial-free music into hotels and restaurants. “The music itself was newly recorded versions of popular songs, but now produced with purposefully mellow, orchestral arrangements,” historian Peter Blecha wrote in 2012.

Research in the 1940s showed that music could influence behavior, and during World War II, Muzak was used to motivate factory and military workers. In the postwar years, the goal shifted to keeping customers in stores, with “soothing, saccharine sounds being pumped into dentists’ offices, grocery stores, airports, and shopping malls all across the nation and overseas,” Blecha explains.

On their journey to the moon in 1969, Apollo 11 astronauts calmed themselves by listening to Muzak. Back on Earth, however, soporific versions of hit songs became known as “elevator music.” In 2011, Mood Media announced that it had acquired Muzak for $345 million, adding to its portfolio of commercial music services for retailers, hotels, restaurants, gyms, and banks. Now supplying music for 470,000 commercial locations around the globe, the company was “delivering unique experiences to millions of people daily.”

Suddenly, elevator music was out; nostalgic pop playlists were in.

In 2020, music still affects shoppers’ moods, but not necessarily in a good way. We Gen Xers feel vaguely insulted when the soundtracks of our youth are cynically used to sell us things. We are this close to buying everything we need online, having it delivered by drones, and listening to our 1980s playlists when we want to, how we want to, in our own homes!

Retailers should take a page from video game designers, who similarly want to keep players engaged for as long as possible. The Legend of Zelda games have gorgeous, critically acclaimed soundtracks, setting the bar for ambient music that’s enjoyable for people of all ages. Why can’t we have original mood music in stores? (Attention, composition majors! A nation turns its lonely eyes to you.)

Until that day, I’ll have to listen to The Cure while going about my mundane errands, draining the music of all meaning. It makes me want to protest in some small but visible way, perhaps by wearing head-to-toe black, dying my hair with shoe polish, and piercing my earlobe with a nail.

By the time I get out of a store that’s recycled my memories to sell toothpaste and dish soap, I’m feeling a little Goth myself.

Featured image: Robert Smith of The Cure, 1985 (AF archive / Alamy Stock Photo)

“If I Couldn’t Tell These Stories, I Would Die”: Lincoln and Laughter

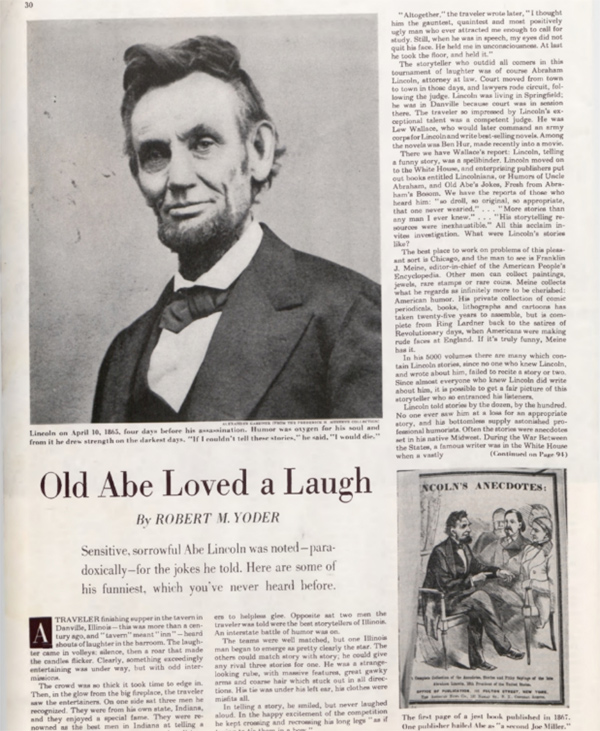

Imagine the unknown Lincoln. Picture the frontier lawyer who stepped onto the national stage — unkempt, gawky, blunt, speaking with a prairie twang in a high voice. And homely. Lord, he was homely.

Lincoln’s contemporaries, seeing him for the first time, might have noticed the same two things that struck Lew Wallace when he first saw Lincoln.

Later in life, Wallace was a best-selling author, a celebrated Union general, and a territorial governor. But in 1851, he was just another attorney who rode the judicial circuit with other lawyers. One evening, just after sundown, he rode into Danville, Illinois, and entered the local tavern. He found it crowded with people attending court business. As he edged his way into the crowd, he heard occasional bursts of laughter over the noise of the bar. Working his way toward the sound, he found that two teams of lawyers from Indiana and Illinois were have a joke-telling contest.

He took particular note of one of the contestants representing Illinois.

He arrested my attention early, partly by his stories, partly by his appearance. Out of the mist of years he comes to me now exactly as he appeared then. His hair was thick, coarse, and defiant; it stood out in every direction. His features were massive, nose long, eyebrows protrusive, mouth large, cheeks hollow, eyes gray and always responsive to the humor. He smiled all the time, but never once did he laugh outright. His hands were large, his arms slender and disproportionately long. His legs were a wonder, particularly when he was in narration; he kept crossing and uncrossing them; sometime it actually seemed he was trying to tie them into a bow-knot. His dress was more than plain; no part of it fit him… Altogether I thought him the gauntest, quaintest, and most positively ugly man.

What was even more memorable to Wallace was Lincoln’s ability to hold a room’s attention — and his apparently bottomless fund of jokes.

About midnight, his competitors were disposed to give in; either their stores were exhausted, or they were tacitly conceding him the crown. From answering them story for story, he gave two or three to their one. At last he took the floor and held it… Such was Abraham Lincoln. And to be perfectly candid, had one stood at my elbow that night in the old tavern and whispered: “Look at him closely. He will one day be president and the savior of his country,” I had laughed at the idea but a little less heartily than I laughed at the man. Afterwards I came to know him better, and then I did not laugh.

Humor was an essential part of Lincoln, and a critical element in his success. As a Congressional candidate, he used it to fire up crowds and put down hecklers. Running for the senate, his humor enabled him to score points off the well known and skilled politician, Stephen Douglas. When, for example, Douglas told a debate crowd that Lincoln was unqualified and unskilled, he added that Lincoln had once run a general store, selling cigars and whiskey. He added, “Mr. Lincoln was a very good bartender.” Lincoln retorted, “Many a time have I stood on one side of the counter… and sold Mr. Douglas whiskey on the other side.”

When Douglas accused Lincoln of being “two faced,” Lincoln shot back, “If I really had two faces, do you think I’d hide behind this one?”

Humor also proved valuable to Lincoln as president. As Robert M. Yoder noted in a 1954 Post article,

If a time-wasting friend lingered too long, Lincoln could disengage himself by telling a story which ended the conversation. He answered questions with stories; he avoided answering by telling stories. If the conversation headed in directions he didn’t like, he could change the subject with a story.

And, as we know now, humor helped Lincoln maintain his sanity.

“If I couldn’t tell these stories,” Lincoln once told a congressman — and gravely—”I would die.” Humor was of tremendous importance to this sensitive and sorrowful man; almost a sort of oxygen for the soul. It offended a good many citizens that Lincoln could joke in times so tragic, but those close to Lincoln understood the emotional process involved. It was jesting-that-I-may-not-weep.

Yoder offered several examples of Lincoln’s jokes. Some are familiar, but the number of unfamiliar stories suggests that Lincoln knew far more jokes than have been recorded.

When a courier appeared at the War Office to announce a major Union victory, the officers were surprised that Lincoln showed no excitement. Lincoln dismissed the courier and cheerfully told the men in the room,

Pay no attention to him… He’s the biggest liar in Washington. He reminds me of an old fisherman I used to know who got such a reputation for stretching the truth that he bought a pair of scales and insisted on weighing every fish in the presence of witnesses. One day a baby was born next door and the doctor borrowed the fisherman’s scales. The baby weighed forty-seven pounds.

Once when he found all his advisers solidly against him, he told this story:

A drunk wandered into a revival meeting and, after mumbling, “Amen,” a few times, fell asleep. As the meeting closed, the preacher cried, “Who are on the Lord’s side?” The congregation stood as one — all except the slumbering drunk. That shout didn’t wake him, but the next one did. “Who are on the devil’s side?” the revivalist cried. That roused the sleeper. Seeing the preacher standing, the drunk rose too. “I didn’t exactly understand the question,” he said warmly, “but I’m with you, parson, to the end.” He looked around at the silent crowd, all seated. “But it seems to me,” said the drunk, “that we’re in a hopeless minority.”

Lincoln’s easy use of humor changed America’s taste in politicians. Previously, Americans had preferred solemn, humorless men with the gravity of Old Testament prophets. We now expect our legislators and presidents to occasionally tell, and laugh at, jokes. We believe a sense of humor reflects a sense of reason and proportion, and an ability to perceive the outrageous.

In many regards, Lincoln was a man ahead of his times. He saw, sooner than most of his contemporaries, what we all recognize: laughter is necessary for keeping our sanity.

Featured image: Library of Congress

Wit’s End: My Punny Valentine

Thirteen years ago this February, my first child was born. In a postpartum sentimental haze, I called him my Valentine’s baby.

Now he is almost a teenager and not quite as cherubic as before. Everyone knows that older kids develop questionable habits, exploring paths that you tried to warn them about, to no avail. They must discover for themselves that certain things — however tempting! — must never be done to excess.

I am speaking, of course, of puns.

Known as the “lowest form of humor,” they are an irresistible draw for seventh graders, who seize upon the chance to be funny and annoying at the same time. Until this year, I thought my son had a sophisticated sense of humor. His dry remarks reflected well on me, I believed. His zany witticisms showed that he came from a creative home!

But that all changed with his class presentation on the religions of Japan, which he proudly described as a pun-heavy monologue called “Tao’s It Going?”

Spurred by the success of this gambit, which made his friends laugh and did not appreciably lower his grade, he started making puns all the time, no better (I’m sorry to say) than “Tao’s it going?”

Some were so ham-handed that I began to doubt he knew what a pun was. The dictionary explains that it is “the use of a word in such a way as to suggest two or more of its meanings or the meaning of another word similar in sound.” But sometimes he would point to my burgundy coat and say, ridiculously, “Are you red-dy to go? Get it? Red-dy?”

“Stop that right now,” I’d snap like Mary Poppins. “What’s the matter with you?”

But the puns, or attempted puns, kept coming.

When we were alone in the car, I tried to impart some knowledge about the responsible use of wordplay. “Sole Desire,” I pointed out, passing a downtown shoe store. “See? That’s a pun. Sole as in shoe, and sole as in only. A lot of businesses have puns for names. A coffee shop named Higher Grounds would be another example.”

After a moment, he piped up: “A Taste of Thigh.”

“What?”

“That place right there. That’s a pun, right?”

“It’s A Taste of Thai! No one would call a restaurant A Taste of Thigh.”

“What if they served, like, pig thighs? Do pigs even have thighs?”

“I don’t know, and I’m not going to think about it.”

He picked up my phone and Googled do pigs have thighs. “They do,” he reported. And around that time, I gave up.

Believe it or not, puns were once considered the mark of the smart set. A good one-quarter of Shakespeare is ribald puns, only one of which I will repeat here. In Romeo and Juliet, one character dies uttering the pun, “Ask for me tomorrow and you shall find me a grave man,” unable to stop making lame jokes because he is bleeding out and probably delirious.

In the Jazz Age, Dorothy Parker was queen of the acerbic pun, like “You can lead a horticulture, but you can’t make her think.” And here’s Oscar Wilde, making fun of a dead German philosopher: “Immanuel doesn’t pun; he Kant.”

In fact, there is something distinctly middle-schoolish about puns, often employed to insult someone, tell racy jokes, or both. Even innocent puns have a disruptive quality: little rebellions against the staid, ordinary use of language.

In Alice in Wonderland, Lewis Carroll’s looking-glass world is full of puns. In “The Mock Turtle’s Story,” for example, the main character explains to Alice:

“When we were little, . . . we went to school in the sea. The master was an old Turtle — we used to call him Tortoise —”

“Why did you call him Tortoise, if he wasn’t one?” Alice asked.

“We called him Tortoise because he taught us,” said the Mock Turtle angrily: “Really you are very dull!”

. . .

“And how many hours a day did you do lessons?” said Alice, in a hurry to change the subject.

“Ten hours the first day,” said the Mock Turtle: “nine the next, and so on.”

“What a curious plan!” exclaimed Alice.

“That’s the reason they’re called lessons,” the Gryphon remarked: “because they lessen from day to day.”

A school report called “Tao’s It Going?” wouldn’t raise an eyebrow in this crowd. (The Tortoise presumably would give it an A.)

No wonder, then, that some middle schoolers have shown a knack for the form. Today’s most familiar pun, often attributed to Mark Twain, was actually coined by eighth grader Florence Kerns. In 1931, Kerns entered a wordplay contest that asked her to use the word denial in a sentence. “Denial river runs through Egypt,” she wrote waggishly, creating the ur-text of the modern version: “Denial ain’t just a river in Egypt.”

In 1934, 14-year-old Margaret Walko placed in a newspaper competition with this gem: “‘Harmony’ times must I tell you to sit down?”

Not to be outdone, in the same contest, 13-year-old Helen Holodak came up with: “Will you ‘wholesome’ of these books for me?”

I know just how their mothers felt.

But in our family’s case, the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree. I can have a needling sense of humor with my son, discussing the Star Wars film The Force Awakens in a Scottish accent (“The Farce Aweekens”) or spontaneously breaking into song (“Mom, please!”). These annoying jokes get him to look up from whatever he’s doing and pay attention to me for a second, reminding him that, even though he’s almost 13, I’m still here. And maybe his silly puns or not-quite-puns around the kitchen do the same.

Though he’s now taller than me, he’ll always be my Valentine’s baby. And come to think of it, he’s kind of a card.

Featured image: freya-photographer / Shutterstock

Wit’s End: Losing Weight with Liz Taylor

In January, many of us pledge to shed excess weight, but as we all know, that’s easier said than done. After my first child was born, I found myself 40 pounds heavier and, after losing half, hit a plateau. The fitness books were filled with hideous prescriptions: counting calories, weighing food, and doing an unpleasant-sounding activity called “reps.”

But I did not want to do any of those things, and the books spooked me. Finally, I stumbled upon one called French Women Don’t Get Fat, by Mireille Guiliano. Its breezy tone assured me that I didn’t have to change my entire personality just to lose weight. A Frenchwoman wouldn’t dream of moving faster than a languid sashay, let alone do “reps.” How absurd!

It was the Francophilic pep talk that I needed, and it got results. But to address the steady upward creep of the scale in my 40s, I need more than the mental image of “being French.”

Enter the American movie star Elizabeth Taylor, one of the most celebrated beauties of all time. Unlike the prototypical Frenchwoman, she did get fat, especially during her marriage to politician John Warner from 1976 to 1982. Stuck at home in Washington, D.C. while Warner worked long hours, Taylor turned to comfort food (and other substances) for solace. “Eating became one of the most pleasant activities I could find to fill the lonely hours and I ate and drank with abandon,” she wrote later.

Taylor was publicly ridiculed for putting on weight in her 40s, but by her 55th birthday was en bonne forme and more glamorous than ever, having “dropped from 180-odd to 122 pounds.” Her 1987 book, Elizabeth Takes Off, tells the story of how she did it and, more importantly, of her extraordinary life. When I saw it in a used bookstore, I pounced on it like a frosted sugar cookie.

Reading the book is like having a vivacious aunt show up at your door, dripping in diamonds, to tell you if she can pull it together, so can you. Born in 1932, Taylor was nine years old when she made her first film, and she spent her childhood working on movie sets. Feisty from the start, in her early teens she told Louis B. Mayer to “go to hell” because she didn’t like the way he spoke to her mother. As a famous young star, she led a sheltered life, guarded by protective parents and studio bosses.

At 17, eager for independence, Taylor entered her first marriage, with seven more to come. Elizabeth Takes Off dwells fondly on her favorite husbands: producer Mike Todd, who died tragically in a plane crash one year after their 1957 wedding; and actor Richard Burton, with whom Taylor shared 11 films and married twice, in 1964 and 1975. She had three children and enjoyed motherhood so much that she adopted a fourth.

“I’ve always admitted that I’m ruled by my passions,” Taylor writes, explaining not just her many marriages but her love of parties, jewelry, and, yes, food. While today’s film actors subsist on soy crumbles and arugula, Liz was a meat-and-potatoes girl who loved burgers, steaks, mashed potatoes, and fries. She once asked a friendly ex-husband to visit her at Dulles Airport during a layover. “And maybe bring some leftover fried chicken. You do have some fried chicken around, don’t you?” Charmed, the ex-husband fried up some chicken and brought it to the airport with a side of fresh corn. And they lived happily ever after.

As she matter-of-factly describes a wild ride of films, marriages, divorces, hospitalizations, and dress fittings, Taylor is a likeable narrator. Despite having owned a giant rock called the Krupp Diamond, she seems an earthy, unpretentious woman with a zest for life. “I confess I love being surrounded by beautiful things and I love being looked after,” she writes (and I confess that I, and every woman strolling the aisles of a Bed, Bath & Beyond, love these things, too).

“When I gained weight, I just bought more clothes,” she writes sensibly. (Nodding.)

When anyone tried to help me, I’d say, ‘Look, I know what I’m doing. I’m going through a phase. I can’t diet until I’m ready, and if you push me, the minute you finish your lecture I will go in and have some hot fudge.’

The minute you finish your lecture, I will go have some hot fudge. I am so using that.

Taylor’s sometimes out-of-control life masked an inner strength, the mental toughness that comes through in her films. After a long run of overeating and other addictive behaviors, she took a hard look in a mirror and didn’t like what she saw. A stint at the Betty Ford Center addressed her alcohol abuse, and with a clear head Taylor realized that she had “been doing a lot of harm to [my] body for an awfully long time . . . . I had actually tossed away my self-respect.”

Husbandless and sober, she came up with her own personal plan for food and exercise. While the first half of Elizabeth Takes Off is autobiography, the second half describes her weight-loss regimen. But first, some general advice: “Get out that full-length mirror,” she instructs in her best bossy-aunt manner. “When you’re trying to diet, it’s no time to play games.” Taylor also advises to “look your best while losing.” She continues:

I know plenty of big ladies who are positively glorious-looking. They may wear a size sixteen or eighteen, but they’re always well groomed, neatly coiffed, and radiantly glamorous. Yet many dieters will throw on anything as long as it’s dark in color. Their philosophy is ‘I’m fat so it doesn’t matter how I look.’ Rubbish. It always matters how you look.

It always matters how you look. Strong words for my drawerful of ratty black yoga pants, Liz! But I hear you.

The diet itself is a curious artifact of the mid-’80s. Breakfast is fruit and whole-wheat toast or a bran muffin; lunches feature low-fat cottage cheese and skinless chicken breasts; and coffee is lightened with “a splash of skim milk.” For someone who liked her hot fudge sundaes, the menu is extremely disciplined, coming in at 1,000-1,200 calories a day. Desserts include a baked apple and something called an orange soufflé, made with “3 tablespoons low-cal margarine,” “2 packets artificial sweetener,” and grated zest.

Even at 30 years’ distance, it’s hard to criticize this diet, though it includes odd items like “barbequed squab” and not one, but two, types of “curried mayonnaise.” If Elizabeth Taylor happily consumed such foods on a tufted divan in her orchid-filled Bel Air estate, with a cabinet of acting awards to her right and an original Renoir to her left, planning her next charity ball on a gold phone, who are we to say Curried Mayonnaise #2 and a tray of raw broccoli is not quite up to par in 2020?

And anyway, you don’t read Elizabeth Takes Off for the recipes. It’s just inspiring to spend 200-plus pages with Aunt Liz, who hastens to add that her low-fat diet allows for occasional “pig-outs,” as she puts it with typical bluntness.

“Guard the assets you were blessed with like a miser,” Taylor instructs, but in the end, she is not unduly obsessed with beauty or weight. “Happily,” she wrote in her 50s, “God made me incredibly resilient and I was able to bounce back. In fact, when someone recently asked me what was my proudest accomplishment, I said with all sincerity: ‘Just being alive.’”

Featured image: Elizabeth Taylor in 1987 (Photo By John Barrett/PHOTOlink.net/MediaPunch/Alamy)

Wit’s End: On Modern Passwords, I’ll Take a Pass

I’ve never gone in for experimental prose. Call me old-fashioned, but I like the basics: structure, coherence, grammar — things like that.

But looking back over my life, I realize I’ve spent countless hours composing edgy, modernist words: random strings of numbers and letters that make a mockery of all meaning. The very sight of them evokes feelings of nihilistic despair.

I’m not trying to be artsy. In fact, I don’t want to make up these words at all. Yet, unless I constantly remember or invent new computer passwords, I am locked out of almost every aspect of my life.

Log into my work laptop? I have to type 52cHeezeball# or no dice.

Pay my kids’ school lunch accounts? 52cHeezeball_@!

Purchase household supplies online? 522CHEezeBALL+++

Check my email? cheezeTOTHEballTOTHEcheezecheezeball_%

Order prints of vacation photos? balmoral*castle(scOTLand)_cheeze?

Watch old sitcoms on streaming video? #princECHARles+cHeeze4ever

Obviously, I can’t remember all these passwords. No one could. When I inevitably forget some random variant of “cheezeball,” I am asked a series of stressful personal questions, a quiz on minor details of my own life:

What was the name of your childhood pet?

Wait, which one? Pass.

Where did you meet your spouse?

Wait, which one? Pass.

What is your father’s mother’s uncle’s middle name?

Um . . . John?

Incorrect! What is your second-favorite food?

Er … tacos, I guess?

Incorrect! Why did William Shakespeare’s last will and testament provide for his wife, Anne Hathaway, to inherit his “second-best bed”? What was Shakespeare implying exactly? Was this some kind of diss to Anne?

Well, scholars disagree —

Incorrect! What is your sun sign in the Zodiac astrological system?

Virgo.

What house is that sign’s ruling planet in right now?

I don’t really keep track of —

You have made too many incorrect guesses. Your account is now locked for suspicious activity. Please contact customer service.

How did we get here? When I was growing up in the 1970s and 1980s, people conducted business in person. If you wanted to buy something, you dragged a squirming child to the store, paid with cash or check, apologized for the mess your child made, and left.

For office work, you rolled a blank page into the electric typewriter and started typing — real sentences with subjects and verbs! Not gibberish.

I first needed a password in college to use the school computer lab. “No problem,” I thought. “I’ll just use ‘cheezeball,’ a simple term I can hold in my fresh young brain.”

But over the decades, passwords horribly multiplied and morphed until we reached the present state, which some have described as a “nightmare.”

That’s a quote from Fernando Corbató, who created the first computer password as a scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the early 1960s. In a 2014 interview with the Wall Street Journal, Corbató — by then a trim, cheerful man of 87 — explained that he was trying to keep researchers from “needlessly nosing around in [each other’s] files.”

But in the 2010s, he said, “I don’t think anybody can possibly remember all the passwords that are issued or set up. That leaves people with two choices. Either you maintain a crib sheet, a mild no-no, or you use some sort of program as a password manager.” Corbató himself kept “three typed pages” of passwords and estimated he had used 150 different ones over the years.

In fact, the use of non-computer passwords dates back to ancient times. One of the earliest recorded passwords was “shibboleth,” a word that makes you sound drunk even when you say it correctly.

In the Old Testament Book of Judges, after two tribes engaged in battle, the winning tribe posted guards at the river so their enemies couldn’t escape. Anyone trying to cross the river was forced to say “shibboleth,” which the tribes pronounced in different ways. One fellow came along and said: “Er . . . sibboleth?” Incorrect! He was promptly slain.

From the beginning, it seems, passwords have been mildly absurd. In 2003, they became more so with the publication of password tips by the National Institute of Standards and Technology. As the Wall Street Journal reported in 2017, the agency “advised people to protect their accounts by inventing awkward new words rife with obscure characters, capital letters and numbers — and to change them regularly.”

These rules were widely adopted by government and corporations, yet the NIST staffer who wrote them, Bill Burr, remarked in 2017: “Much of what I did I now regret.” By then retired and with the benefit of 20/20 hindsight, Burr admitted that constantly-changing passwords, larded with nonsense characters, actually don’t work very well.

Great, now you tell me! When I am neck-deep in the Cheezeball Variations and every function I perform is locked away behind a Cheezeball Wall, or CHeezeWaLL_9$8, because that’s just how I think now.

The most unsettling thing about today’s passwords is that they don’t stand between you and enemy territory or exclusive clubs. Unlike a Roman soldier in 300 B.C., I don’t need a watchword to protect my garrison from barbarian hordes. Unlike in the Prohibition Era, I don’t need a code to get into an underground speakeasy where people are singing “shibboleth” with boozy abandon.

Instead, I need complex passwords to pay the water bill and email my mom. The secret space is my own life, and the codes reside in my own faltering memory. What if, one day, I simply can’t remember “cheezeball”? Is “the cloud” going to recognize me somehow and allow me back into my virtual world? Not likely.

Luckily, there will still be a few who know me without passwords. My husband and kids will not require verification of my identity. My loyal dog will not insist on two-factor authentication.

And when I join the ultimate secret club, I doubt I’ll have to recite random numbers and letters. Passing on will be password-free. I expect it will go something like this:

“Hello, it’s me.”

“Oh, hello! Come on in.”

Featured image: Shutterstock

Fall Out of Favor

I was at the hardware store the other day and overheard a man tell Ed, the manager, that fall was his favorite time of year. Ed, because he’s congenial and likes to keep his customers happy, agreed that fall was a wonderful season, but I could tell he was lying because no one with half a brain likes fall. The glories of summer are past, the drudgeries of winter are looming, and along comes fall, dressed to the nines, promising what she can’t deliver. Fall is the politician pledging to drain the swamp, the alcoholic vowing to turn over a new leaf, the televangelist guaranteeing a miracle. Fall is the carnival barker of seasons, beguiling us one moment, picking our pockets the next.

I was thumbing through my mind recently, recollecting whether anything good has ever happened to me in the fall, and couldn’t think of one thing. I met my wife in the summer and married her two summers later. My sons were born in the winter and summer, my granddaughter in the winter. I’ve been fired twice in my life, both times in the throes of autumn. One October, a semi-truck hauling tofu ran a red light and T-boned me, obliterating my favorite truck, combining in one fell swoop the three things I most despise — semis, tofu, and October.

I once took a test on the internet to find out the month and year of my death based on my health, lifestyle, and age. I hit the Enter button, watched the circle spin at the center of my screen, and then was informed I’ll clock out in 2052, at the age of 92, in the month of October. It didn’t say how I will die, though I’m certain my death will be autumn-related — eaten by a bear accumulating fat for the winter, run over by a distracted leaf-gawker, or sucked into a combine.

Fall is the politician pledging to drain the swamp, the alcoholic vowing to turn over a new leaf, the televangelist guaranteeing a miracle.

I’m not saying fall is without its charms. The leaves are beautiful, once one overlooks their suicidal habit of hurling themselves to the ground and skittering across the earth, clicking like rickety bones. I do enjoy the Laodicean weather, neither hot nor cold, and therefore pleasing to me, if not to God. Then again, fall’s vacillation is troubling, its effort to please everyone, its constant search for the middle ground, to be all things to all people. Say what you will about summer and winter, at least they have the courage of their convictions, even if they kill us with heatstroke or hypothermia.

As I write this, it occurs to me I’m not that fond of winter either, which means half my life, from October to March, is a miserable slog. Fortunately, I like spring and summer twice as much as anyone, so it comes out even in the end.

I recently read a story of a man coming out of a six-month coma. I hope if I’m ever in a coma it starts in early fall and ends just as winter is concluding. My family would be gathered around my bed upon my awakening.

“Don’t you remember anything from the past six months?” my wife would ask.

“Not the first thing,” I would happily report.

It takes a man of resolute courage to so openly scorn a season everyone else admires, but I’m not one to be swayed by public opinion, no matter how strongly the winds of judgment blow.

If I ever have enough money, I’m going to buy a second home in Australia, so that when autumn starts here, I can move there for six months, just when spring is starting.

This article is featured in the September/October 2019 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Taken For A Ride: Around the Midwest on a Triumph Bonneville

In an earlier issue (May/June 2018), I mentioned I would be taking a solo motorcycle trip south along the Mississippi River on my 1974 Triumph Bonneville. Several Post readers wrote asking if they could join me, one of whom was a woman wanting to know whether I was married and if I might like a little company. Apparently, there is nothing like a motorcycle trip to excite the imagination.

I’m pleased to report the trip was a success, though it went nothing like I had planned. When Rod Collester, my friend and a vintage Triumph expert, learned my intentions, he advised me not to ride a 44-year-old motorcycle with an oil leak rivaling the Exxon Valdez halfway across the country. Fortunately, I also own a new Triumph Bonneville that from a hundred yards away looks a lot like my old Triumph Bonneville, which, as we say in Indiana, is close enough for government work, so I rode it instead.

Then two friends, Ned and Mike, heard of my trip and asked if they could come along, and I said yes, even though they ride a Honda and a Harley Davidson. While I never hold someone’s gender, religion, race, national origin, or sexual orientation against them, I have been known to look down my nose at people with so little regard for Triumph motorcycles that they would ride something else. But I swallowed my pride and invited them to join me, provided they refrain from making snide comments about the size of my motorcycle (900cc) compared to theirs (1300 and 1800 ccs). They kept their word for the first hundred miles, and then Ned referred to my bike as a “moped” and Mike laughed so hard he snotted himself.

By some quirk of fate, we left on our trip the same day the tropical cyclone Alberto hit landfall in the Gulf Coast, spawning storms and record rainfall along our intended route. Instead of heading south, we rode northwest 350 miles to Galena, Illinois, where Ulysses S. Grant was living when the Civil War broke out, working as a clerk at his father’s store, a job he despised but took because he was broke. If you ever feel like giving up, it might help to remember that in 1857, Grant pawned his watch to buy Christmas gifts for his family, then 10 years later was a national hero, well on his way to the presidency. (Grant was so virtuous, I can’t help but think that if the motorcycle had been invented then, he would have ridden a Triumph Bonneville.) We spent the night at the DeSoto House Hotel, built in 1855 and named after Hernando De Soto, who was purported to have discovered the Mississippi River on May 8, 1541, much to the surprise of the Native Americans who were already there, many of whom he promptly killed.

In Olney, a storm struck from the northwest, and I prayed it would give birth to a tornado and kill me dead.

The next morning, dodging Alberto’s offspring, we rode south along the Great River Road to Fort Madison, Iowa. If you’ve ever eaten Armour bacon, then in a roundabout way you’ve visited Fort Madison, too, since their processing plant is southwest of town along Highway 61. The scent of meat hangs over the place, a not altogether unpleasant aroma. Every town should be so fortunate to smell like bacon. We stayed the night in a Super 8 motel owned by a man from India who, though unintelligible, was thoroughly helpful. I’m not sure why so many Indians own hotels in America, and I don’t care so long as the rooms are clean and they have a TV channel that shows The Andy Griffith Show and Gunsmoke.

The next day found us in Hannibal, Missouri, the hometown of Mark Twain, which we would never have figured out except for the Mark Twain Hotel, the Mark Twain Restaurant, the Mark Twain Cave, the Mark Twain Antique Shop, the Mark Twain Museum, Mark Twain Avenue, the Mark Twain Boyhood Home, the Mark Twain Memorial Lighthouse, and the Mark Twain Brewing Company, where Mike, against our advice, danced on a table. Continuing southward, we eventually crossed the Mississippi on the Golden Eagle ferry, motored seven pleasant miles across the Brussels peninsula, ferried across the Illinois River, and stayed the night at the Pere Marquette State Park Lodge, built by the Civilian Conservation Corps during the Great Depression. The next time someone tells you the government can’t do anything right, take them to the Pere Marquette State Park Lodge six miles west of Grafton, Illinois, and show them what America did when it had intelligent and visionary leaders.

If on the Judgment Day I am sentenced to hell, I will appeal the verdict by pointing out that I have already been there, on U.S. 50 crossing Illinois from Lebanon to Lawrenceville, an unrelentingly boring stretch of road 119 miles in length that felt like a thousand. In Olney, a storm struck from the northwest, and I prayed it would give birth to a tornado and kill me dead. Alas, I was not so fortunate and entered Indiana at Vincennes, the hometown of my parents and, coincidentally, Ned’s residence while serving as a district superintendent for the United Methodist Church during his years of checkered employment. I asked Ned if he wanted to go off the bypass and ride through town and he said “God, no,” or something to that effect. I could only conclude that when he left Vincennes, he had been asked never to return.

We continued east on U.S. 50 through Amish country down to French Lick, hometown of basketball legend Larry Bird, where we stopped for dinner at the West Baden Hotel and ate grilled cheese sandwiches, the only thing on the menu we could afford. From there, we rode through the countryside to our farmhouse in Young’s Creek, built by my wife’s grandfather, Linus Apple, in 1913 and restored 98 years later by my wife and me before I spent all our money on motorcycles.

The next day found us heading north toward home, a formerly bucolic drive until Indiana’s governor, three governors ago, had the bright idea to turn a perfectly good state highway into an interstate, transforming a two-hour jaunt into a four-hour Sisyphean slog. I rolled into our garage five days and 1,123 miles after our departure and remain, to this day, a jaded and weary man, worn down by the road and my association with two dubious characters. Next year, I am informed, we will tackle the Natchez Trace Parkway through Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee. I can hardly wait.

Philip Gulley is a Quaker pastor and author of 22 books, including the Harmony and Hope series featuring Sam Gardner.

This article appears in the November/December 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Humorists on Humor: Cracking the Code on What Cracks Us Up

World Telegram & Sun Photo by Fred Palumbo/Library of Congress

One of the most popular writers of his day, James Thurber was, to use his own words, a wit, satirist, and humorist. As he explained, “The wit makes fun of other persons; the satirist makes fun of the world; the humorist makes fun of himself.” Named for him, the Thurber Prize for American Humor is awarded annually to recognize the art of humor writing; the 2017 winner will be announced at Caroline’s Comedy Club in New York City on October 2, 2017. The Post invited previous prize winners and finalists to share thoughts on the art of being funny today.

What characterizes modern American humor?

“People talk about the perils of being politically correct, but in a way it’s just the opposite. There’s so much more you can say now than you could 30 years ago. Louis C.K.’s comedy routines are a case in point, but there are writers who push the envelope just as far. What used to be on the edge is now family humor.”

—Calvin Trillin

Novelist, poet, food writer, regular contributor to The New Yorker; author of Quite Enough of Calvin Trillin

“I tend to write political satire. But I decided that American politics have reached the point of being sufficiently self-satirizing, so for my recent book, The Relic Master, I travel backward in time to the year 1517. And you know, I had such a good time doing it I may just stay in the 16th century. And while it’s probably true that a lot of the comic/satirical energy has shifted to TV, there’s still an awful lot of good stuff being written these days.”

—Christopher Buckley

Novelist, essayist, critic, memoirist; author of No Way to Treat a First Lady

“Humor is less filtered now than it used to be, it’s darker, more inappropriate, but at the same time humor with heart reigns supreme. It’s hard to characterize the humor scene today because it’s so diverse. It’s become a conduit for political issues, for social, class, and gender issues. Is it possible ‘funny’ is getting too ‘serious’? People still want to laugh, but they also want a really good story to go along with it.”

—Sloane Crosley

Essayist, novelist; author of I Was Told There’d Be Cake

What qualities does good humor writing have, and can it be learned?

“Essentially, you take an essential truth and twist it, turn something upside down so it’s seen in unexpected ways. That’s the heart of it. Afterward, there are matters of timing and pacing, a rhythm you need to establish. Throw in some elements of storytelling. Build up, push back, build the tension, and finally you hit the mark. I used to think humor couldn’t possibly be learned, but now I absolutely believe it can. ”

—Laurie Notaro

Journalist, novelist; author of The Idiot Girl and the Flaming Tantrum of Death

“I don’t know how Thurber would do these days. His agent would probably tell him he needs to get a sitcom before he can shop his book around.”

—Dan Zevin

“I think you can analyze what makes good humor. And you can sum up techniques of how to make it work. But something like that would end up in the Journal of Structural Engineering. It would be that dull.”

—John Kenney

Novelist, regular contributor to The New Yorker; author of Truth in Advertising

Where does humor come from? Is there a humor impulse?

“I don’t think it’s a humor impulse. It’s a story impulse. After the idea comes to you, you have to think what form it will work best in — a short piece, a novel, the theater, late-night TV show. I’m blessed that I’ve been able to work in all those forms, so I can decide which one works the best. Maybe next I’ll try writing a pamphlet.”

—Alan Zweibel

Screenwriter (Saturday Night Live), playwright, novelist; author of The Other Shulman

Do you find humor comes out of your own experiences?

“Of course, although I had trouble finding anything funny about turning 80. At least I don’t have to take my shoes off at the airport anymore.”

—Calvin Trillin

Do you see any difference in the humor between men and women?

“I think men and women are equally funny, but because men’s experiences are way different from women’s, it makes for a difference in perspective. That makes us different but equal in a number of ways.”

—Laurie Notaro

“Tina Fey and Lena Dunham have both written staggering, laugh-out-loud funny books. Many of the funniest people writing today are women.”

—John Kenney

Do the internet and social media have an impact on contemporary humor?

“I find a lot of cool, interesting voices on the internet that you won’t find anywhere else. You can publish and reach an audience there that you can’t anywhere else. That means that someone in Minnesota who works at a power company can publish short pieces of comedy that people anywhere in the world can find and laugh at. Through the internet, the sky’s the limit as far as creativity.”

—Steve Hely

Screenwriter (30 Rock, The Office); Author of How I Became a Famous Novelist

Would you consider the humor on American television to be literary in its broadest sense?

“Only written humor, written by one person, published on paper, in a book or magazine, is literary humor. TV sitcom scripts, screenplays, blog posts, transcripts of stand-up routines are all fine, but none come close to literary humor. Every so often, a work of literary humor lasts forever. A few pieces by Thurber fall in that category. Ditto S.J. Perelman and Robert Benchley. Roy Blount is a great literary humorist, as are Garrison Keillor and David Sedaris.

—Ian Frazier

Essayist, staff writer at The New Yorker; author of Lamentations of the Father

“From a book-publishing perspective, I think humor writing is in great shape, just as long as you’re a famous TV star. I don’t know how Thurber would do these days. His agent would probably tell him he needs to get a sitcom before he can shop his book around town. Or at least he’d need an Instagram account. He’d probably be taking selfies with his dogs instead of drawing them.”

—Dan Zevin

NPR contributor; author of Dan Gets a Minivan: Life at the Intersection of Dude and Dad

Laugh Lines

On Parenting: “Parenthood is an amazing opportunity to be able to ruin someone from scratch.”

—Jon Stewart

On Social Media: “Getting your news from Twitter is like asking a cat for directions.”

—Andy Borowitz

On Politics: “Politicians and diapers must be changed often, and for the same reason.”

—Mark Twain

On Marriage: “Never marry a man you wouldn’t want to be divorced from.”

—Nora Ephron

On Religion: “Anyone who thinks sitting in church can make you a Christian must also think that sitting in a garage can make you a car.”

—Garrison Keillor

On Taxes: “Tax reform is taking the taxes off things that have been taxed in the past and putting taxes on things that haven’t been taxed before.”

—Art Buchwald

On Women: “Women are wiser than men because they know less and understand more.”

—James Thurber

On Death: “That would be a good thing for them to cut on my tombstone: Wherever she went, including here, it was against her better judgment”

— Dorothy Parker