The Mask Slackers of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic

The orders from many governors and mayors during the current COVID-19 pandemic have been similar: stay at home, leave only for essential trips, no gatherings. The toll of stay-at-home orders on businesses has been severe, sparking small and large protests around the country to open these states and municipalities back up, invoking the infringement on people’s individual liberties.

The last pandemic of similar proportions, the Influenza pandemic of 1918, triggered a comparable patchwork of ordinances and ensuing economic fallout. Some Americans’ reactions a century ago took similar form, particularly a group of fed up San Franciscans who called themselves the “Anti-Mask League.” Although San Francisco saw one of the worst U.S. outbreaks of the pandemic, these dissidents opposed orders from the city’s Board of Health not because of the economic implications, but because they saw it as their right to walk the city maskless. Besides, they didn’t think the things were working anyway.

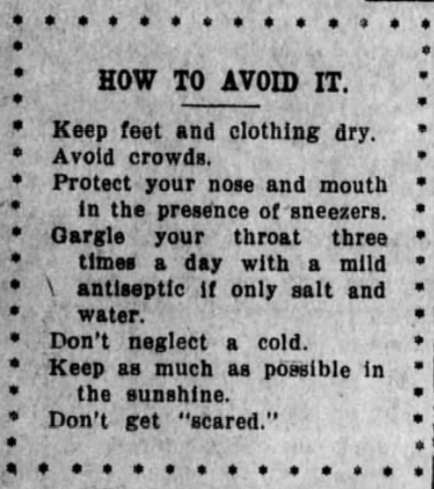

By September of 1918, it was clear that “Spanish influenza” was a serious virus with enormously destructive potential in the U.S. A press release in newspapers on September 25th warned readers to “Avoid crowds” and “Protect your nose and mouth” as well as less explicitly heedable advice like “Keep as much in the sunshine as possible” and “Don’t get ‘scared.’” The message to the public echoed the patriotic tone cultivated during the war: “Only by loyal and intelligent co-operation of the general public can the epidemic of Spanish influenza be prevented from spreading thruout the country and hampering our war work. Do your bit” (J.H. Duckworth). Dr. Gordon Henry Hirschberg made a significant request of Americans a few weeks later that was printed prolifically: “Kissing is another prolific method of infection, and this practice should be stopped except in cases where it is absolutely indispensable to happiness. Kissing between members of the gentle sex can certainly be abolished without hardship.”

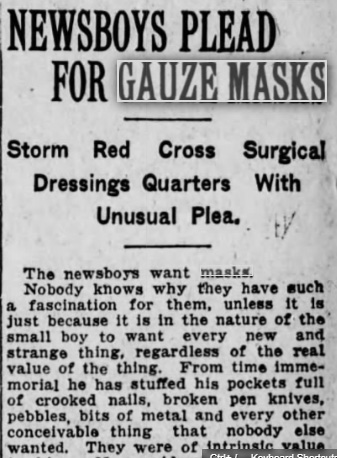

The importance of gauze masks in the anti-flu effort, especially for medical workers, was considered paramount. Leading the effort was the American Red Cross. The organization had grown from a little more than 100 local chapters at the beginning of World War I to almost 4,000 by its end. In October of 1918, the U.S. Surgeon General requested that the American Red Cross “assume charge of supplying all the needed nursing personnel and furnish emergency supplies.” The ARC mobilized nurses and mask-makers across the country, compelling women to get to work sewing gauze masks.

That month, cities began enforcing mask requirements. In Canada, railway passengers were refused admittance without masks. Iron River, Wisconsin — having experienced a bad outbreak — required mask-wearing in public. Tucson and San Diego passed ordinances mandating mask-wearing for store workers, and other cities did the same for barbers and nurses.

On October 17th, San Francisco closed churches, schools, theaters, “cabarets, and merry-go-rounds” to slow the spread of the virus. The city’s Board of Health, led by Dr. William C. Hassler, instituted a mask ordinance. The fine for disobedience was five dollars, which was then given to the Red Cross. Although several cities in California had such ordinances, the rule was never enforced statewide. In San Francisco, 100 people were arrested in October — reported in the news as “mask slackers” — and nine of them were sent to jail. In Stockton, California, one policeman apparently found his own father to be a mask slacker, and he arrested him, according to the Sacramento Bee.

Hassler assured his city that if everyone complied with the tight restrictions they would soon see influenza cases decline, after which they could go about business as usual. Oddly, the Health Officer also reportedly endorsed a massive sing-along in Golden Gate Park in mid-November, saying that as long as everyone wore their masks, it would “be in the nature of an experiment to see what effect music has on the influenza bacillus.” Hassler was also caught without a mask at a boxing match a few days later, maintaining that he must have moved it to smoke a cigar when the photo was snapped. Still, throughout November, San Francisco saw days with zero new cases of the disease, and, on November 21st, they unmasked at noon. Hassler declared the epidemic to be over.

In December, however, cases in San Francisco started to creep back up, and Hassler called for everyone to mask up again. The Board of Supervisors voted against reinstating his ordinance though, on December 19th, one arguing that it was unfair “to the businessmen of San Francisco.” The meeting was described in the Sacramento Bee next to a public service announcement declaring “Spanish Influenza More Deadly than War.”

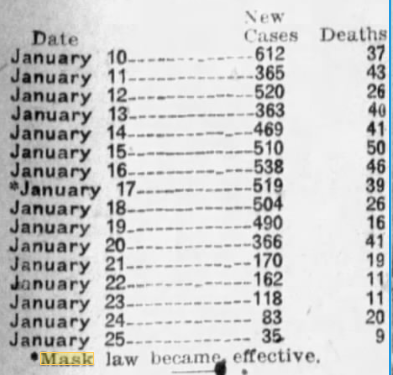

Going into 1919, cases in San Francisco continued to rise. On January 17th, the Board of Supervisors gave in to Hassler’s request, putting the mask requirement back into place. At that meeting, a San Franciscan announced she had organized an Anti-Mask League whose purpose was to “oppose by lawful means the compulsory wearing of masks.”

The Anti-Mask League met that weekend and declared themselves “Sanitary Spartacans.” They claimed the masks were useless and demanded the mayor repeal the ordinance requiring them. The group was led by a Board member and several doctors. The next week they held a meeting at Dreamland Rink, and 2,000 people showed up. They read bulletins from the State Board of Health “showing compulsory mask-wearing to be a failure” and urged attendees to “not submit to the domination of a few politicians and political doctors.” Simultaneously, the number of new cases in San Francisco was dropping each day since the second mask ordinance had been implemented. The League attended a Board meeting and hissed at supporters of the ordinance.

San Franciscans wrote into the Chronicle’s “People’s Safety Valve” section, deriding the ordinance and moaning that “the muzzle is a farce and an outrage against our liberties.” One man claimed his short beard was “the best kind of a mask, as it not only keeps the bronchial tubes in good condition, but it is better than any gauze mask for catching microbes.”

People complained that the Board ought to dedicate itself to cleaning up the city instead of implementing “autocratic” rules. The vocal opposers to the mask ordinance couldn’t believe that nine out of ten San Franciscans supported it, as was reported, since they claimed many people on the streets weren’t wearing them. The Chronicle even questioned the efficacy of face masks in an article, positing that more data would make clearer whether or not they were working.

San Francisco’s numbers continued to drop, though, and come February, the “gauze law” was scrapped. The Anti-Mask League presumably disbanded, having no more measures to oppose. People were free to roam the streets maskless without worrying about fines or arrest, and Hassler touted his rule for creating a 1000 percent decrease in cases over 11 days. Once again, he declared the end of the epidemic in San Francisco.

Featured image: Theater advertisement in the Sacramento Bee, January 1919

Vintage Ads: Selling Health and Hygiene During the 1918 Pandemic

February 22, 1919

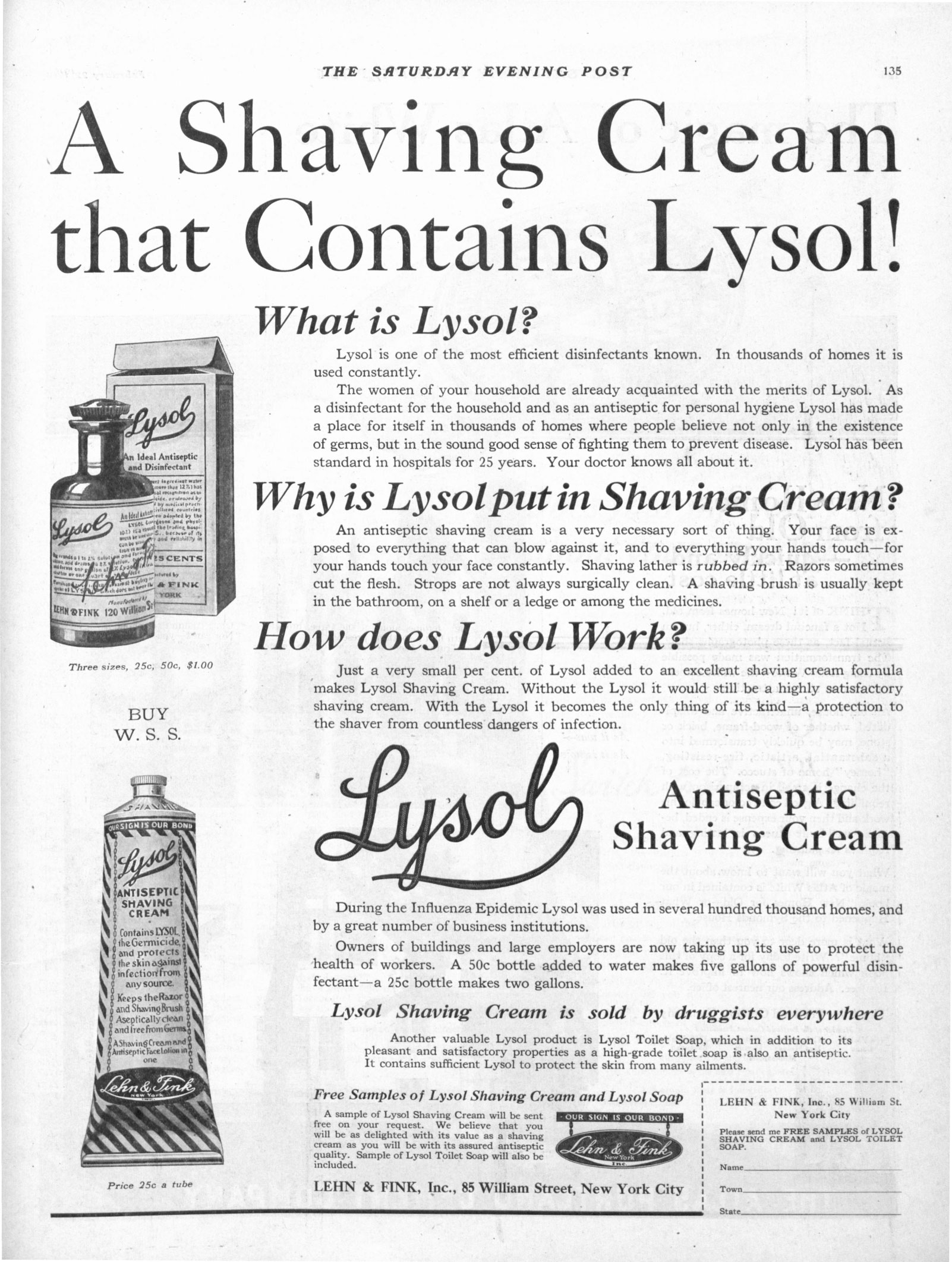

“During the Influenza Epidemic Lysol was used in several hundred thousand homes, and by a great number of business institutions.” (Click to Enlarge)

February 2, 1918

“…has earned its place in the esteem of surgeons, physicians, dentists and public by its own distinctive virtues in preventing infection in wounds and as a lotion, douche, garble, mouthwash and in matter of personal hygiene.” (Click to Enlarge)

February 8, 1919

“High ideals and cheerful service—Toilet and Hygienic Preparations of a purity to satisfy the most exacting standards.” (Click to Enlarge)

February 8, 1919

“Epidemics and typhoid have resulted from the use of unsanitary, wrong-principled water coolers.” (Click to Enlarge)

February 8, 1919

“This pure, white family soap cleanses quickly and with the thoroughness appreciated by particular housewives.” (Click to Enlarge)

December 28, 1928

“Diseased hands, dirty hands, sweaty hands, millions of all kinds of hands grasp the car-strap. And car-straps cannot be kept clean; and they abound with all kinds of disease germs.”

April 20, 1918

“…colds, influenza and grippe are contagious, too. Their germs should be destroyed. So with all germs that lurk in dark places or breed in close rooms. The way to rid the home of them is gaseous fumigation.” (Click to Enlarge)

March 8, 1919

“To combat coughs, influenza and pneumonia, see that the air in your home is not only warmed but that it is AUTOMATICALLY circulated; that it is AUTOMATICALLY moistened; and that it is permanently free from dust, gas and smoke.” (Click to Enlarge)

The Truth About “Swine Flu”

The H1N1 influenza pandemic in 2009 grabbed headlines under the unfortunate moniker “swine flu.” In the ensuing panic, countries banned imports of U.S. pork and American citizens also shunned pork, believing it to be dangerous. Eventually the influenza strain’s formal name, H1N1, took hold, but the term “swine flu” still elicits fear—and confusion—among the public.

So how did the uproar over “swine flu” get started?

Dr. James Lowe, a swine veterinarian at the University of Illinois College of Veterinary Medicine in Urbana, recently offered a brief primer on influenza as well as some background on the 2009 flu outbreak. Food animal veterinarians play an important role in protecting public health by ensuring a safe food supply, but influenza is not a disease that is spread by eating meat, so worries connecting pork and flu are entirely unfounded.

“The virus that causes influenza is genetically unstable, meaning it evolves rapidly,” says Dr. Lowe. “The influenza virus changes so quickly that scientists who develop vaccines must race to try to keep ahead of it.”

Whereas vaccines developed to prevent tetanus and measles remain effective for years because the infective agents that cause these diseases change little, the flu vaccine must be updated every year. Flu shots are designed to protect against a few strains of the influenza virus that are predicted to be common in a given flu season.

“Most mammals and birds are affected by influenza,” says Dr. Lowe. “Scientists categorize influenza A strains according to two proteins found on the surface of the virus: hemagglutinin—hence the “H”—which has 17 variations, and neuraminidase—“N”—with 9 variations. The structure of these proteins differs from strain to strain because of rapid genetic mutation.”

Strains of the influenza virus affect various species differently. For example, people are usually only affected by the H1, H2, and H3 and the N1 and N2 strains. Some of these variations also affect birds and pigs. Strains arising in different species can combine to form novel strains that may affect more than one species.

There are three strains of influenza now circulating in U.S. pigs that also affect people: H1N1, H1N2, and H3N2. The flu is spread primarily by exposure to the virus through coughs and sneezes. It is just as possible for people to give the flu to pigs as it is for pigs to give the flu to people.

Pigs and people experience much the same manifestations of flu: runny noses, cough, and high fevers. The deadly aspect of influenza occurs if it damages the airways, allowing secondary infections to set in.

For people, key strategies for keeping flu-free are washing hands and staying home if infected. For pigs, modern farms have very stringent biosecurity protocols that prevent people from bringing pathogens in or out of the farm.

Although it was called “swine flu,” H1N1 is historically a human flu. It was the culprit in the 1918 pandemic Spanish Flu.

The H1N1 flu outbreak of 2009 originated in Mexico. Ironically the first cases of the 2009 outbreak that affected U.S. pigs were traced to sick farm workers who had contracted the illness from schoolchildren.

Despite dire warnings in the media and a fearful public, the number of U.S. deaths attributed to the pandemic H1N1 outbreak between April 2009 and April 2010 was estimated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to fall between 9,000 and 18,000—well below the 40,000 U.S. deaths attributed to seasonal flu in a typical year.

The influenza virus is a frustrating virus to deal with, even when it is not deadly. It causes major economic losses in people and pigs: people lose productivity and incur medical bills, and pigs don’t grow well so farmers lose income.

The truth is, new strains of the virus will continually appear, and from time to time a new strain will cause more severe illness than is typical. But there is no true “swine flu,” and certainly not one that is guaranteed to be deadly in people.

It is simply the flu, we can all get it, and we all try our best to avoid it.

If you have questions about infectious diseases that pass between people and animals, your local veterinarian can be an excellent resource.

Andrea Lin is an Information Specialist at The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign College of Veterinary Medicine.