Awesome Nuts & Chews

Trish pursed her lips and blew a long, thin plume of cigarette smoke out her bathroom window. She didn’t mind having to hide the smoking. In fact, she was pleased her children had been so brainwashed by the nuns. Cigarettes, booze, blow — it was all the same to them.

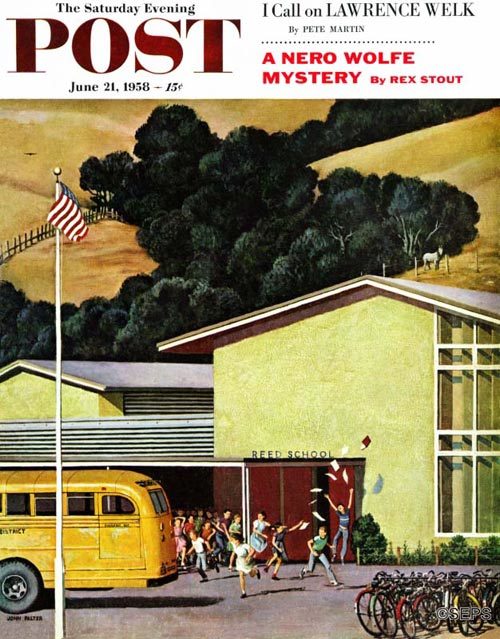

Outside the day was bright and silent, the rural street blanketed with snow. Carly, the baby, was asleep in her crib. John Michael, age 11, and the twins, 8, were out selling holiday candy for their school. She disliked these fundraisers even more than the bake sales and wreath sales. There was something indecent about children selling door-to-door. But her opinion carried no weight. At St. Michaels, the candy sale was a fact of life. Treats & Treasures, Season’s Delights, Holiday Cheer; cheap candy, fancy boxes, the same as she’d once sold.

Mayhem erupted all at once, Carly shrieking to get her out of her crib, the three boys yelling and pounding on the back door. Trish tightened the drawstring of her sweatpants, threw the half smoked cigarette in the toilet and flushed.

She scooped her 2½-year-old daughter up from her crib. Five years after she’d thought she was through having babies, then along came Carly. The thought of having another child horrified her. But Kevin dreamt it would be a girl and told her “God has his ways.”

She changed Carly’s diaper, trotted downstairs with Carly planted on her hip, and opened the door. The boys exploded into the kitchen. Under their woolen caps, they all had the same small diamond-shaped face as Trish, the same dark eyes shot with streaks of green. Carly was fairer, blonder, fleshier, like her father.

“Don’t you dare come any further with those wet snow boots,” said Trish, pining for the next cigarette.

At five-thirty, her husband, Kevin, manager and part owner of the Friendly’s in town, strolled in. When Mork & Mindy ended everyone headed for the dining room table: Kevin at the head, Carly and Sean on one side, John Michael and Lucas on the other. Trish served meatloaf and potatoes swimming in thick brown gravy. The children had plastic cups of milk. Kevin had Mountain Dew; Trish, her bottle of Perrier.

“I don’t want meatloaf. It looks like dog food,” said Lucas.

“It’s delicious,” said Kevin, raising his fork to his mouth. “Your mother is a wonderful cook.” When Trish got up to get the ketchup and white bread, he patted her on the rear end. She turned, ready to scowl, but his round baby-soft face and playful eyes made it impossible for her to be annoyed. The meal progressed with finger pointing and name-calling while Trish doled out the warnings.

“You know my cousin Eddie, the one who lived in Essex?” said Kevin. Kevin had hundreds of cousins. “The one with the earring. He called me. He lives in New York now, got a job at MTV. They’re having some sort of blowout Christmas party and he wants us there. To give him moral support, I guess. Anyway, I said okay.”

“You hate New York, Kevin,” said Trish, unable to ignore a stirring in her blood, a rich soft wanting of her past.

“I figured you’d be thrilled. Kevin smirked. “Hey, wouldn’t it be a hoot if we ran into Ethan?”

“That’s ridiculous, Kevin. There are ten million people in New York.”

“He’s some kind of famous sound engineer, isn’t he?”

She hoped her face wasn’t as red as it felt. Kevin got a kick out of teasing her about her first marriage. The little he knew about the time she’d spent in New York with Ethan titillated him. She suspected he was secretly proud of having a wife with such a thorny past.

“Who’s Ethan?” said Sean.

“Never mind. You have two peas left,” snapped Trish.

“Will you buy some candy from me?” said John Michael, breaking the silence.

“What are you selling?” asked Kevin.

John Michael whipped the brochures out from under his seat.

“And me,” shouted Carly, tipping over her cup of milk onto Lucas.

“Whoa!” shouted Lucas. Kevin sprang up for a dish towel and winked at Trish.

She scanned the brochure absentmindedly. How ironic, that the love pats and winks that first attract you to someone, inevitably become the gestures you dislike the most, thought Trish.

“I’ll take the Awesome Nuts & Chews,” she said with a weary smile.

They’d been married for 12 years. Trish had come back from New York to Wellsboro, devastated by her failed marriage, and there was Kevin, smiling in a doorway. He called her his ex-actress, Trish the Dish. They’d dated in high school. Even then, he didn’t make the earth move, but he was comfortable and dependable. A year after her return, she was married in the blue steeple church where she’d once taken communion. Within five years they had three boys. They moved into a sage green shingled colonial on a windy country road, two miles from her parents, three from his. She drove the station wagon; he, a tomato-red Mazda. Eventually the memories of her days in New York and the late nights got folded away like heavy blankets in spring. She’d packed away Ethan and the divorce until everything from her former life was safely out of sight.

Smoking in the bathroom, Trish mentally flicked through her closet for an outfit. She imagined the floor-to-ceiling windows, tea-lights and top shelf liquor. As the week ground on, the anticipation grew. On the night of the party she shaved her under arms and legs even though Kevin never touched them when they made love. (Five minutes kissing on the mouth, five minutes per breast, and five minutes of rubbing between her legs; he was always on top.) It wasn’t fear but worry that made her keep her resentment of Kevin’s lumpy lovemaking to herself. There were too many more important things at stake. His dignity, her home, their family. She tried on a paisley mini-dress, then a pantsuit with padded shoulders, before settling on a black cocktail dress she’d worn to several cousins’ weddings and her diamond studded cross.

The party was in a loft on Prince Street. Kevin and Trish stood at the open door staring into the darkness. Paper lanterns were strung across the rough wooden beams. Pat Benatar’s voice whined overhead, the sound seeming to emanate directly from the pipes on the exposed ceiling. Yep, thought Trish, Love is a Battlefield.

“Is it safe to go in?’ asked Kevin.

Trish pulled him through the heavy metal door towards two catty-cornered couches piled with coats. Kevin kept his corduroy barn jacket on. Despite the draft rushing in through the casement windows, she laid her scarf and coat onto the heap of clothes. It was when she straightened up that she recognized Ethan sitting on an armchair underneath the row of windows. Her head snapped back towards Kevin. She wanted to look but didn’t dare turn back. She gripped his hand and steered him through the clusters of people towards the back of the room, her heart thudding hard and fast.

“Jeez, it stinks in here,” said Kevin. “Something is killing my eyeballs.” Trish inhaled the pungent Vics Vaporub odor. She led Kevin past a row of chafing dishes on the red and green linen-draped tables to the bar in the corner of the room and asked for a tequila and coke for herself and a Budweiser for Kevin.

“I wonder what that smell was.” said Kevin.

“Poppers,” said Trish, sipping her drink. Kevin’s forehead wrinkled. “Amyl nitrate.”

“Oh,” he said.

Kevin had no idea what she knew or where she’d been before they married. He knew nothing about rooftop parties, the ecstasy, the blow. He thought she left Ethan because of the abortion. Kevin didn’t know Ethan became a different person with each person he met. When Trish became pregnant, four years into their marriage, so much of her love had already been tainted by the booze and dope and their long-standing argument about having a baby. She’d fantasized sticking a pinhole in her diaphragm. Then it happened — the diaphragm failed all by itself. She begged him to keep the baby. He said he would leave her if she didn’t get rid of it. I can’t give you the white picket fence you want, he said. It was when he insisted on the abortion, she realized he was incapable of being an adult.

Trish met Ethan right after she graduated Rosehill College for Women. She’d come to New York with the dream of becoming an actress. The first time she’d spent the night they made love again in the morning and he brought her breakfast in bed, fancy coffee, fresh squeezed juice and a cheesy spinach omelet. She literally skipped across Central Park to get to an audition. She’d never experienced that kind of intensity with anyone, whether they were making love or screaming at each other on the top of their lungs, their passion was absolute.

But she hadn’t known then, that someone who drinks every day and calls it his relaxation, is an alcoholic. One or two was never enough, whether it was Absolut or Tuinols or lines of coke. When Ethan drank, he became another person, loud and self-pitying. He drank the morning he came home from the Lionel Ritchie tour and discovered Trish lying on the couch with warm blood oozing onto the hospital pad between her legs. He hadn’t thought she’d take care of it so quickly. He cried as he drank, saying over and over that he wasn’t good enough for her, banging his head against the wall. It sickened her to watch. She closed her eyes, the cramps bending her in half, reminding her how much she’d wanted that baby. That morning, she let him drink until he blacked out.

“Are you all right?” Kevin said over the blare of Prince’s Little Red Corvette.

“Of course, I’m just checking things out. Another tequila and coke,” she said to the bartender.

“Honey, don’t you think you should slow down?” said Kevin.

“Another, please,” she said, winking at Kevin. “Come on, let’s find Eddie.”

They moved diagonally through the crowd towards the other end of the loft. Trish lit a cigarette. Kevin frowned. A waitress wearing a miniskirt and an MTV Santa cap held out a tray of bacon-wrapped shrimp. Kevin stabbed three with one toothpick. They threaded past a cluster of people getting high, someone held out a joint to Kevin.

“No, thank you,” he said, guiding Trish forward by the waist. “Are all New York parties like this?”

The tequila was starting to mellow her. “Only the good ones,” she said.

Near a side wall, Eddie was holding court. He slapped Kevin on the back and pumped his hand. Trish got an enormous bear hug and a kiss on the lips that lasted just a little too long, reminding her what it was she didn’t like about him. He asked about their kids, the mortgage, the Mazda. Kevin seemed visibly relaxed to be with someone he knew. Trish tossed back her drink and excused herself, Eddie pointing the way to the bathroom.

Out of their view, she lit another cigarette and headed back towards the bar. She was feeling good, but hardly good enough. Tonight she wanted to be a younger version of herself, the hot party girl she hoped she’d been years before when she had married Ethan. And she wanted to glow, for Ethan to know how content she was now.

It wasn’t long before she spotted him again, his back to her, at the opposite end of the food table. Though he no longer had a ponytail, she knew it was him by his short, compact build. His hair was clipped in a crew cut and he wore a tight fitting white T-shirt. A few years ago, she’d found out from a friend she still kept in touch with in New York that he’d given up the drugs and stopped drinking altogether. She also knew from his elderly mother in Albany, whom she still spoke to, that he’d become a health nut. Why not back then, when it would have mattered, she thought.

Trish stared at his back and willed him to turn around, to look at her, still eye-catching, still fun-loving, a mother of four children. A woman glided up to him and slipped her arm around his waist. She was petite and dark haired, like Trish, wearing a sleeveless red dress and thick gold bangles. Trish felt like she’d been hit in the head with a metal swing.

She walked into the bathroom holding her third, or was it her fourth drink? The room reeked of hairspray and smoke. Trish gazed at the women on either side of her, their faces reflected next to her in the mirror, heads tilted up as they painted their eyes. Three other women huddled together by the last sink near the huge window, getting high. Marijuana smoke snaked around her, rising above the stall doors. A woman with a masculine build, pancake makeup and fiery orange hair, turned and handed her a joint. She accepted gratefully, inhaled and closed her eyes. It was potent, smoothing out the heavy alcoholic high.

The first time she’d ever smoked weed was on a date with Kevin. They were both seventeen, parked in his Camaro in a deserted Dairy Queen lot. She remembered the way he carefully removed the tiny forbidden reefer from the baggie and presented it to her in the palm of his hand as if it were a rare, precious jewel. Everything became more. Their tongues in each other’s mouth hotter, the speckled stars brighter, the smell of the summer heat richer. She let him touch her breasts, and they rubbed each other over their clothes, all the while wondering whether she’d fallen in love.

“You all right, honey?” said the woman with the burlesque makeup plucking another joint from her cigarette case.

“I’m good, thank you. Do you think I could possibly buy another one of those from you?” she asked.

She ducked into a stall. The blunt felt natural in her hand. She smoked quickly, leaning against the stall door. An image of the three boys as toddlers crammed together in the bathroom with her flashed through her mind. By now, they would be on their third or fourth Goonies video. Kevin’s sister would be squirting whipped cream on their hot chocolates.

She wandered back into the loft. The air clung to her body. Her arms felt damp, her lips chapped, despite the Barbie pink lipstick. She needed a drink to dull the heightened sense of herself. “Hello again,” said the bartender. The tequila and coke disappeared in two gulps, transforming her into a carefree spirit. She turned and swayed, remembering this same light, dreamy feeling with Ethan, lying in the crook of his shoulder, sipping Dom Perignon, snorting grams at twilight on their rooftop, evenings at the Beacon, Village Vanguard, Arlene’s Grocery, Bowery Ballroom. He got comped for every show in town. She remembered his generosity, the instant parties with dozens of friends radiating around his inexhaustible stash. Making love on satin sheets in executive suites at the Fountainbleau, the Drake, the Wilshire Grand. Ethan used to say he knew when she was about to come because her tongue got cold and her fists tightened against his ribcage. She would never fit into someone that way again, never again come with someone’s face between her legs, never love anyone that much or be hurt that badly.

Now, where is my Kevin, she thought, peering into the oily faces of punk artists, roaming into another room where beams of colored light spun across the floor and a handful of people were dancing.

“Where have you been? I’ve been looking all over for you,” said Kevin, clutching the sleeve of her shrug. “I waited at the door of the ladies room forever.”

“I must have missed you,” she said, smiling at the crazy patterns on the dance floor. The lights made her dizzy, but she liked them.

“What’s the matter with you? You look funny.”

“I’m drunk.”

Eddie bounded his way towards them.

“Oh, there you two are,” he yelled. “Kev, dude, I want you to meet my buddies. This is Roger, the fastest drummer in New York. And this is Ethan, the most awesome soundman in the business. He did the show for Arcade Fire and Billy Joel at the Garden. Kevin and Trish came down from the boonies for our little holiday bash.”

Trish’s face bloomed red. “How the hell are you, Ethan?”

Ethan nodded with a kind of detached cool.

“You know each other?” said Eddie.

“Oh Eth and I go way back. Kevin, this is Ethan, the man you’ve been dying to meet. Ethan. Kevin. Kevin. Ethan.” The girl in the red dress strolled up to Ethan holding two bottles of Tab. “And this must be Suzie, or is it Sherry. Or is it Shirley bringing you a Shirley Temple,” said Trish stiffling a giggle. She snatched the beer bottle out of Kevin’s hand and threw her head back. The beer dribbled down her neck. “Whoops. No point crying over spilled beer, huh Eth?”

“Honey, I think it’s time to go home. It was a great party.” Kevin gripped Trish by the elbow.

“I want to dance,” shouted Trish, twisting away, out onto the dance floor. “Come on Kev, it’s a slow one, just the way you like it.” Be a man, she thought. I want to self-destruct.

Grudgingly he took hold of her. She gave him a wet sloppy kiss. He pulled his face away. Every time you go away, you take a piece of me with you she sang along with the music. But then she had to stop. Her head slumped onto Kevin’s shoulder. Ethan stood like a state trooper watching her. She knew he was watching. She knew she was wrecked. The room spun around Ethan, the colored lights shooting out in all directions, exploding against him and the girl in the red dress. Aren’t I still pretty? Still amazing? she wanted to ask Ethan. The last thing she remembered was throwing up on the door of the Mazda.

Trish awoke in the family room feeling crumbs under the cushion where she’d buried her toes. It was bitter cold and pitch black. Her ears rang, her throat was raw, her head hot and prickly. Gradually familiar shapes emerged from the dawn shadows. Socks. Jeans. Chutes and Ladders. Double Trouble. An empty bowl. She let out a sigh. But the room started turning so she closed her eyes and hugged her purse, which was wet from her saliva.

Carly burst into the room demanding breakfast. Trish staggered into the kitchen.

Life, Cheerios, Raisin Bran, Total, Special K. “Which one?” she mumbled with one eye squinting open. “That one,” said Carly pointing to the Fruit Loops on another counter. Somehow she opened the refrigerator. The gallon of milk shook in Trish’s hand, gushing into and over the bowl as she poured it.

“Mommy you spilled.”

“Shsh. It’s okay, Boo. You can help me clean it later. Go watch Scooby Doo.”

Fighting to keep her eyes open, Trish stumbled out of the kitchen towards the stairs. On the fourth step up her legs gave way and she crawled the rest of the way up. She fell onto the bed where she slept on and off until late afternoon.

When she awoke, she felt shrouded in guilt and, despite the hangover, turned into a cleaning machine, tearing through every room in the house, dusting, sweeping, vacuuming, sponging. She did three loads of laundry, cooked a tuna casserole, baked a loaf of banana bread, and later that night after the kids were in bed, sat on the white rocker in Carly’s room and rocked.

A week later, the candy arrived: three huge cartons of it. Kevin had sold at Friendly’s, Trish to relatives, both hers and his. Everyone gathered together in the family room to sort and label the candy. The toys and games had been neatly stacked on the shelves of the white, laminated wall unit. Not only had Trish dusted underneath the TV and VCR but she’d climbed on a chair to wipe off Kevin’s model cars and the boys’ soccer trophies. Through the sliding glass doors, it was snowing; snow zooming sideways in great sheets, the trees at the edge of the property invisible in the white wind.

“Where are they? Where are the order forms you dumb-butts?” said Sean, rifling through one of the small drawers in the wall unit.

Trish glared at him from the gingham couch where she’d been playing thumbsies with Lucas. “Dumbutts, dumbutts, buttmuts,” mimicked Carly, who was perched on her father’s lap in the chair at the desk.

“Get out of the way. Let me look,” said John Michael.

“Hey, I was sitting there,” Sean said, plopping himself directly on top of Lucas.

“No you weren’t. You were looking.”

“Move over.”

“They’ve got to be there,” said Kevin calmly. “They’ve got to be here somewhere.”

“There’s plenty of room for both of you,” said Trish, rising.

“This is how you were sitting with your legs all spread apart. You’re taking up the whole couch.”

“I was here first.”

“Shut up. I can’t find the forms,” said John Michael.

“I saw papers in the wagon,” said Carly. The twins sprang up and dumped over the wagon full of Barbies and stuffed animals.

“Well they’ve got to be somewhere,” said Kevin again. “How will we know who bought what?”

“Half the people haven’t paid yet,” said Trish. She thought about her cleaning rampage, but she would never have thrown out the order forms. Or would she? “They’ve got to be somewhere!” She went over to John Michael and nudged him aside to search the drawers herself.

“Let’s look upstairs,” said Sean. He popped up, trotted out of the room, but before he reached the doorway, Lucas grabbed his sleeve, yanked him back and took off.

“I find them,” yelled Carly.

Trish felt like strangling Lucas.

“Look, if it comes down to it and we can’t find them, we can always put up a sign in St. Michael’s asking people to come and claim their candy,” said Kevin.

“What if they don’t remember what they bought?” said John Michael.

“What if someone claims they paid and didn’t?” said Trish.

“In Wellsboro?” said Kevin.

He’s so naïve, thought Trish. “Do you have any idea how much money we’ll lose if we don’t find them?”

“I’m making a sign,” he insisted.

“No you aren’t. You are not going to embarrass this family in front of the whole town. We’ll look like idiots,” said Trish. John Michael started yanking records from a shelf. Kevin swiveled around to face Trish. His usually happy eyes were hurt-looking, as if the blue had run out of them.

“Why’d you do it? Why’d you have to ruin everything?”

Trish froze.

“What are you two talking about?” said John Michael.

“I already told you, I wanted to have a good time. That’s all.” She knelt down by the cartons and began removing candy boxes, stacking them in piles.

“A good time? You were shitfaced, Patricia.”

“Make a sign, Dad. You have to do it,” whined John Michael.

“He is not making a sign.”

“Where are those freaking forms,” cried John Michael flinging a record at the pile of boxes.

“Pick that up,” growled Trish.

“It’s okay for you and Daddy to yell and swear and wreck everything. But not me. Right? Right?” he shouted.

“That’s enough. Go to your room.” John Michael stared defiantly at her. “Now,” she shouted.

Trish turned to Kevin. “I can’t explain it,” she said.

“You disappeared and got stinking drunk and God knows what else, and you can’t explain it!”

Carly lay down in the middle of the doorway with her hands clapped over her ears, yelling. “Stop, stop, stop.”

“Not in front of Carly, okay?” said Trish.

“Of course not, honey. Never in front of the children,” said Kevin and stalked out.

They made the children go out in the snow, at least to the people they remembered selling to. Ten boxes went to neighbors and a dozen more went to family members. One night Lucas busted Sean’s lunchbox claiming the forms could have gotten stuck in it. Trish flew into a rage. “He’s your brother and you torture him,” she cried, slapping him hard on the bottom. She rarely hit her children, a pat on the rear every now and then. Having lost control, she was beside herself with shame and remorse. Forty-six boxes of unclaimed candy sat in four neat piles by the sliding glass doors in the family room.

Late that night Carly screamed out. Trish bolted upright. “I’ll go,” she said, throwing on a flannel shirt and racing into Carly’s room. Kevin patted her shoulder tenderly and rolled over.

The shrieking and thrashing didn’t stop, not after Trish bent over the crib to rub her daughter’s back, not after she turned on the overhead light and picked her up and paced the room, gently pressing her damp head against her shoulder, murmuring, “It’s okay Boo, it’s okay,” thinking don’t let it be a night terror like the ones Sean used to have.

Trying to calm her, Trish wandered from room to room on the first floor, balancing Carly on her hip, pointing and peering out each window, soothing her child, wiping her nose and mentioning several times that children around the world were asleep in their beds. Then, without warning, Carly dropped off to sleep. Too exhausted to climb the stairs, holding a limp toddler, she collapsed on the couch in the family room and fell asleep with warm little Carly lying on her chest.

When Trish awoke, the room was bathed in purple-pink light. The TV was on low. Carly sat on a candy box sucking her thumb, hypnotized by the TV.

“I want candy, Mommy.”

“So do I, Boo,” said Trish leaning over to grab a box. She tore off the cellophane and plucked out a peanut butter cup for herself and her daughter. Then another and another and another. Outside, the deck and backyard were covered in snow as fine as baby powder. Simple and white, all the edges gone from the world.

Featured image: Angel McNall Photography / Shutterstock

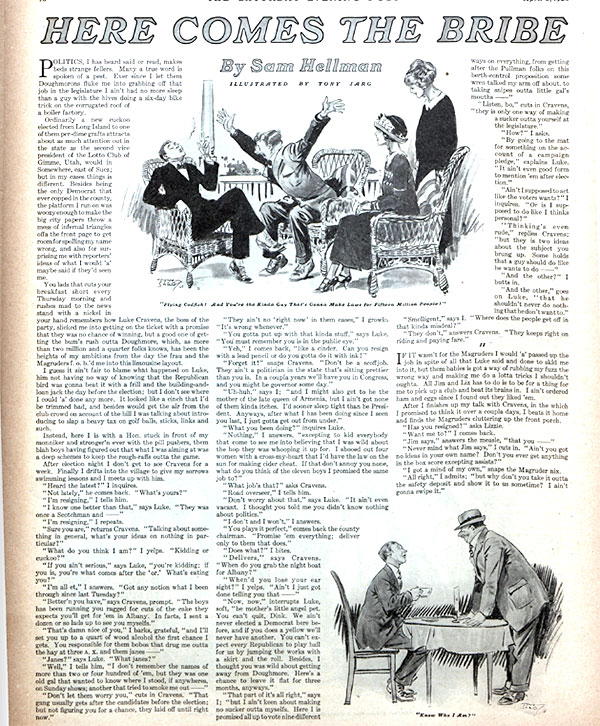

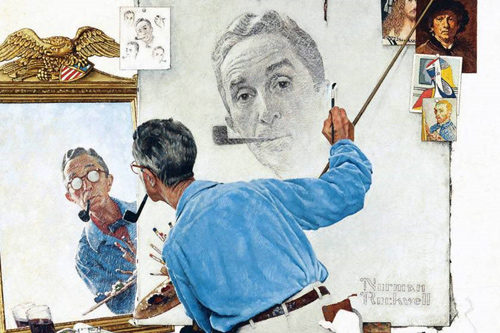

“Here Comes the Bribe” by Sam Hellman

A newspaper reporter and fiction writer with a healthy sense of self-deprecation, Sam Hellman wrote in 1925 that “those who have been reading my stuff will hardly believe that I am a college graduate with an early academic penchant for Greek accusatives and Latin gerundives.” In his humorous stories, witty commoners with crude dialect dress each other down in farcical situations. In spite of his highbrow studies, Hellman observed people and their language while traveling the country after college. In “Here Comes the Bribe,” a scrappy Long Islander accidentally finds success in politics.

Published on April 5, 1924

Politics, I has heard said or read, makes beds strange fellers. Many a true word is spoken of a pest. Ever since I let them Doughmorons fluke me into grabbing off that job in the legislature I ain’t had no more sleep than a guy with the hives doing a six-day bike trick on the corrugated roof of a boiler factory.

Ordinarily a new cuckoo elected from Long Island to one of them per-dime grafts attracts about as much attention out in the state as the second vice president of the Lotto Club of Gimme, Utah, would in Somewhere, east of Suez; but in my cases things is different. Besides being the only Democrat that ever copped in the county, the platform I run on was woozy enough to make the big city papers throw a mess of infernal triangles offa the front page to get room for spelling my name wrong, and also for surprising me with reporters’ ideas of what I would ’a’ maybe said if they’d seen me.

You lads that cuts your breakfast short every Thursday morning and rushes mad to the news stand with a nickel in your hand remembers how Luke Cravens, the boss of the party, slicked me into getting on the ticket with a promise that they was no chance of winning, but a good one of getting the bum’s rush outta Doughmore, which, as more than two million and a quarter folks knows, has been the heights of my ambitions from the day the frau and the Magruders f.o.b.’d me into this limousine layout.

I guess it ain’t fair to blame what happened on Luke, him not having no way of knowing that the Republican bird was gonna beat it with a frill and the building-and-loan jack the day before the election; but I don’t see where I could ’a’ done anymore. It looked like a cinch that I’d be trimmed bad, and besides would get the air from the club crowd on account of the bill I was talking about introducing to slap a heavy tax on golf balls, sticks, links and such.

Instead, here I is with a Hon. stuck in front of my monniker and stronger’n ever with the pill pushers, them blah boys having figured out that what I was aiming at was a deep schemes to keep the rough-raffs outta the game.

After election night I don’t get to see Cravens for a week. Finally, I drifts into the village to give my sorrows swimming lessons and I meets up with him.

“Heard the latest?” I inquires.

“Not lately,” he comes back. “What’s yours?”

“I’m resigning,” I tells him.

“I know one better than that,” says Luke. “They was once a Scotchman and — ”

“I’m resigning,” I repeats.

“Sure you are,” returns Cravens. “Talking about something in general, what’s your ideas on nothing in particular?”

“What do you think I am?” I yelps. “Kidding or cuckoo?”

“If you ain’t serious,” says Luke, “you’re kidding; if you is, you’re what comes after the ‘or.’ What’s eating you?”

“I’m all et,” I answers. “Got any notion what I been through since last Tuesday?”

“Better’n you have,” says Cravens, prompt. “The boys has been running you ragged for cuts of the cake they expects you’ll get for ’em in Albany. In facts, I sent a dozen or so lads up to see you myselfs.”

“That’s damn nice of you,” I barks, grateful, “and I’ll set you up to a quart of wood alcohol the first chance I gets. You responsible for them bobos that drug me outta the hay at three a.m. and them janes — ”

“Janes?” says Luke. “What janes?”

“Well,” I tells him, “I don’t remember the names of more than two or four hundred of ‘em, but they was one old gal that wanted to know where I stood, if anywheres, on Sunday shows; another that tried to smoke me out — ”

“Don’t let them worry you,” cuts in Cravens. “That gang usually gets after the candidates before the election; but not figuring you for a chance, they laid off until right now.”

“They ain’t no ‘right now’ in them cases,” I growls. “It’s wrong whenever.”

“You gotta put up with that kinda stuff,” says Luke. “You must remember you is in the public eye.”

“Yeh,” I comes back, “like a cinder. Can you resign with a lead pencil or do you gotta do it with ink?”

“Forget it!” snaps Cravens. “Don’t be a scoffjob. They ain’t a politician in the state that’s sitting prettier than you is. In a coupla years we’ll have you in Congress, and you might be governor someday.”

“Uh-huh,” says I; “and I might also get to be the mother of the late queen of Armenia, but I ain’t got none of them kinda itches. I’d sooner sleep tight than be President. Anyways, after what I has been doing since I seen you last, I just gotta get out from under.”

“What you been doing?” inquires Luke.

“Nothing,” I answers, “excepting to kid everybody that come to see me into believing that I was wild about the hop they was whooping it up for. I shooed out four women with a cross-my-heart that I’d have the law on the sun for making cider cheat. If that don’t annoy you none, what do you think of the eleven boys I promised the same job to?”

“What job’s that?” asks Cravens.

“Road overseer,” I tells him.

“Don’t worry about that,” says Luke. “It ain’t even vacant. I thought you told me you didn’t know nothing about politics.”

“I don’t and I won’t,” I answers.

“You plays it perfect,” comes back the County chairman. “Promise ’em everything; deliver only to them that does.”

“Does what?” I bites.

“Delivers,” says Cravens. “When do you grab the night boat for Albany?”

“When’d you lose your ear sight?” I yelps. “Ain’t I just got done telling you that — ”

“Now, now,” interrupts Luke, soft, “be mother’s little angel pet. You can’t quit, Dink. We ain’t never elected a Democrat here before, and if you does a yellow we’ll never have another. You can’t expect every Republican to play ball for us by jumping the works with a skirt and the roll. Besides, I thought you was wild about getting away from Doughmore. Here’s a chance to leave it flat for three months, anyways.”

“That part of it’s all right,” says I; “but I ain’t keen about making no sucker outta myselfs. Here I is promised all up to vote nine different ways on everything, from getting after the Pullman folks on this berth-control proposition some wren talked my arm off about, to taking snipes outta little gal’s mouths — ”

“Listen, bo,” cuts in Cravens, “they is only one way of making a sucker outta yourself at the legislature.”

“How?” I asks.

“By going to the mat for something on the account of a campaign pledge,” explains Luke. “It ain’t even good form to mention ’em after election.”

“Ain’t I supposed to act like the voters wants?” I inquires. “Or is I supposed to do like I thinks personal?”

“Thinking’s even rude,” replies Cravens; “but they is two ideas about the subject you brung up. Some holds that a guy should do like he wants to do — ”

“And the other?” I butts in.

“And the other,” goes on Luke, “that he shouldn’t never do nothing that he don’t want to.”

“Smelligent,” says I. “Where does the people get off in that kinda misdeal?”

“They don’t,” answers Cravens. “They keeps right on riding and paying fare.”

II

If it wasn’t for the Magruders I would ’a’ passed up the job in spite of all that Luke said and done to skid me into it, but them babies is got a way of rubbing my fuzz the wrong way and making me do a lotta tricks I shouldn’t oughta. All Jim and Liz has to do is to be for a thing for me to pick up a club and beat its brains in. I ain’t ordered ham and eggs since I found out they liked ’em.

After I finishes up my talk with Cravens, in the which I promised to think it over a couple days, I beats it home and finds the Magruders cluttering up the front porch.

“Has you resigned?” asks Lizzie.

“Want me to?” I comes back.

“Jim says,” answers the measle, “that you — ”

“Never mind what Jim says,” I cuts in. “Ain’t you got no ideas in your own name? Don’t you ever get anything in the box score excepting assists?”

“I got a mind of my own,” snaps the Magruder nix.

“All right,” I admits; “but why don’t you take it outta the safety deposit and show it to us sometime? I ain’t gonna swipe it.”

“I wouldn’t trust a politician,” says Lizzie, cold; “not even with nothing.”

“Is you really gonna take the job?” butts in Jim, quick, to cover up his wife’s fox paws.

“Why not?” I inquires.

“Well,” says he, “it’s a pretty dirty game, ain’t it?”

“Ever play in it?” I wants to know.

“I wouldn’t touch it with a six-foot pole,” he comes back. “They ain’t nobody in politics but a lotta grafters.”

“We once lived in a house,” says I, “where we had a furnace that was always on the bum. One day it got so cold I went downstairs to see what the hell. I found out the janitor was peddling the coal I’d bought and hadn’t taken the ashes out for a month. So I canned him, cleaned the thing out myself and never did have no trouble after that.”

“You should oughta get the kinda furnace we is got,” remarks Lizzie. “Jim says — ”

“The furnace I’m talking about,” I continues, “is a figure in speech.”

“Ours is a Little Diamond Hot Box, ain’t it, Jim?” inquires the sciatica.

“Where’d Lizzie go?” I asks, acting kinda surprised.

“I’m here,” she answers, wide-eyed.

“You’re here, all right,” says I; “but you ain’t there. What I was trying to broadcast,” I goes on, turning to Magruder, “before that frau of yourn turned on the statics, was the idea that if you don’t like dirt you can’t cuss it outta the room; you gotta grab a broom and sweep.”

“I suppose,” sneers Jim, “you’re gonna make politics as clean as a hind tooth, huh?”

“I’ll maybe try,” I answers. “What’ll you do? Stand around while some dip frisks your pockets and bawl out the coppers instead of taking a crack at the crook?”

“Jim ain’t afraid of nothing,” says Lizzie.

“I ain’t afraid of my wife neither,” I shoots back.

“You calling me nothing?” busts out the misses, who ain’t said a word so far.

“Not a thing,” I returns, hasty. “You vote at the last election, Jim?”

“What for?” he comes back. “They don’t count ’em anyways.”

“Well,” says I, “it’s a cinch they don’t count them that ain’t cast. When I gets to Albany — ”

“So you’re going?” interrupts Magruder.

“Yeh,” I tells him. “I kinda feels that I owes that much to prosperity. I’m looking ahead to the time when Dink O’Day Day will be celebrated from Rock Bound, Maine, to Climate, California, and when statutes of me in the parks will be as thick as empty shoe boxes after a church picnic.”

“You’ll look swell in the legislature,” sarcastics Jim. “What do you know about parlor-mantel law?”

“No more’n I know about kitchen-sink law,” I admits; “but it won’t take me more’n a minute and a half to run it down and make it drop from exhaustion.”

“I never seen a guy hate his wife’s husband like you does,” says Magruder. “Ever hear of Roberts’ Rules and Orders?”

“I don’t wear no man’s collars,” I answers, “and that bird Roberts ain’t gonna give me no orders. Anyways, Luke Cravens is the boss of the district. Where does this Roberts boy — ”

“You wouldn’t understand,” cuts in Magruder, “even if you knew. For example, suppose you was to get on the floor of the house — ”

“Who’s gonna put me there?” I yelps. I don’t want you to get no ideas I’m such a stupe as I sounds, but I’m even willing to carry that reputation for the pleasures of razz-jazzing Magruder.

“I mean,” he explains, “if you was making a speech on some bill and a bobo should get up and move that it should be put on the table, what would you do?”

“It all depends,” I answers, “on the way he said it. If he was nice and polite, I’d put it there; but if he tried to rough-bluff me into doing it, I’d leave it just where it was and he’d probably spend the next few minutes picking a inkwell outta his hair.”

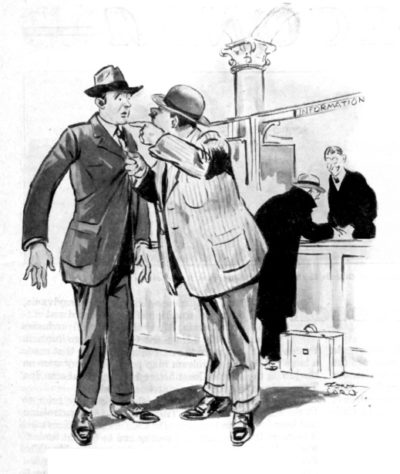

“Flying codfish!” hollers Jim, waving his hands like a yell leader. “And you’re the kinda guy that’s gonna make laws for fifteen million people!”

“That’s what,” says I; “but what do you expects if right thinkers like you won’t take no interest in politics and’d rather play golf than vote?”

“Talking about golf,” comes back Magruder, “is you really gonna introduce that tax bill?”

“I’ll tell the popeyed world I am,” I replies. “A dollar on each ball and five fish on each club.”

“Think you can put over a grab like that?” he asks.

“I wouldn’t be so surprised,” I answers. “When I gets done telling the boys about the terrible housing conditions of the ducks on Long Island on account of the land being drug out from under ’em for golf courses, I expects the tax’ll go with one big sob. D’you know things is so bad on the North Shore that seven and eight ducks is gotta sleep on one rock?”

“I didn’t even know ducks slept on rocks,” remarks Lizzie.

“You should study national science, gal,” I returns. “What’d you suppose they slept on? Credit? Where’d you imagine the expression ‘duck on the rock’ come from?”

“I don’t know,” says she.

“I don’t know the name of the saloon neither,” cuts in Kate, slipping me the glare to sidetrack. “Please stop teasing Lizzie and try and give a imitation of talking sense.”

“Who should I imitate?” I inquires. “Jim?”

“You couldn’t go further and do worse,” suggests the Magruder exposed nerve; and when I starts laughing she goes on, all flustered, “I means, you could go further and do no worse.”

“That’ll be enough,” yelps Jim. “I’ll do my own answering back from now and on. Cutting the kidding cold,” he continues, turning to me, “I thought that golf-tax idea of yourn was to keep the cheap johns from building links around Doughmore and the other swell clubs.”

“Even a natural error like you,” says I, “couldn’t be no wronger. Can you see me pulling chestnuts at a fire for the plutocats around here? I’m a friend of the common people and — ”

“The commoner, the friendlier,” interrupts the frau.

“Maybe,” I admits; “but I promised the duck growers of this district that I’d go to the front for ’em, and a promise and a performance with Dink O’Day is as alike as two peas in a puddle. Experts has tried with instruments and them slow movie cameras to find a difference between ’em, but without no luck. It was funny. Oncet they was studying a promise of mine, and when I told ’em after a coupla hours it was really a regular performance and not no promise a-tall, they just gave up.”

“Doing business with a politician,” remarks Magruder, “I guess they hadda. When you gets to Albany them experts’ll be able to leave their naked eyes at home and still see the difference.”

“What makes you think so?” I inquires.

“Didn’t I hear you tell that Glumph woman you was gonna pass a law to stop all picture shows on Sunday, Wednesday and the nights the Ladies’ Aid met?” asks Jim.

“You did,” I tells him.

“Yeh,” jeers Magruder; “and wasn’t I there when you promised Mildew down at the Tivoli that you’d put the censors on the hummer and fix it so the film folks could do anything they wanted to, within reason and without?”

“Such is the case and the facts in it,” I confesses. “What about it?”

“How you gonna keep both promises?” demands Jim.

“What,” says I, “leaving out present company, could be simpler? I’ll introduce the bill the Glumph frill wants and also the one Mildew’s after.”

“How,” yelps Magruder, “can you be on both sides at oncet?”

“Ah,” I returns, “that’s what makes politics a art. What’s wrong with the way I’m doing? Some of the folks in the county wants this; some others don’t want that. Who’m I to say what’s proper for ’em? I’m just like a waiter in a restaurant. Everybody that comes in asks for something different. I puts in the order. If the chef don’t wanna cook up the mess, whose fault is it? A jane drifts in with her trap all set for a pair of fried wizzle-wumph eggs, sunny side up. Is it my business to tell her they ain’t good for her complexions and try and set her up to a platter of raw ox ears?”

“You mean rare, don’t you?” inquires Lizzie.

“I don’t know no more what you’re talking about than you do,” says Jim; “but how you gonna vote on these different things when its comes to a show-down?”

“O’Day,” I replies, “is far enough down on the roll call for my judgment and my conscience to get together before I has to. I’m gonna introduce everything that anyone wants and let ’em take their chances. Personally, nothing don’t interest me excepting my duck bill, and I shall fight for it with all the powers I has, with faith in the right and — ”

“Oh, hire a hall!” snaps Magruder.

“The Monday Club’s got a dandy place,” says Lizzie. “You can get it for fifty dollars a night; besides, they is still got the decorations up from the Pappa Eta Motza sorority dance.”

III

Me and Cravens goes to Albany together, Luke figuring on introducing me around to the high moguls of the party and seeing that I get started off K.O.

“You’ll be kinda busy getting settled,” says he, “so I has taken a little work off your hands.”

“What work?” I asks.

“Well,” he answers, “I figures they is about eight jobs you’ll get to hand to the boys in the district and I’ve picked ’em for you. Seeing as I got you into this, the leastest I can do is to save you from being bothered. I has even notified the lads we’s named.”

“That’s nice,” says I; “but — ”

“’S all right, Dink,” cuts in Luke. “They ain’t no thanks necessary. It’s maybe taken up some of my time and all that; but when I likes a guy, going to trouble for him’s a pleasure.”

“Yeh,” I returns; “but how about them fifty or sixty birds I promised plums to?”

“Albany,” answers Cravens, prompt, “is quite a town. They is a coupla good hotels, and I knows a restaurant I’ll take you to, where you orders tea and gets what you meant.”

Not caring nothing about them jobs at Doughmore, I don’t chase the subject no further. Anyways, I don’t aim to stay long. My ideas is to stick around the legislature just enough to see what makes the thing tick and maybe pull a stunt or two that’ll get me in bad with the jokes at home, after which me and politics’ll call it a day.

Luke makes me acquainted with a bunch of bobos that is supposed to run the works and winds up by taking me to the mansion to meet the governor. He turns out to be a decent feller.

“I has heard a lot about you,” says he to me.

“I’ve seen your name mentioned, too,” I comes back, not to be undone in courtesies.

“I wanna talk to you someday about taxes,” he goes on. “I understands you has studied ’em deep.”

“Governor,” I replies, “I don’t wanna brag, but if they is anything about taxes I don’t know it musta been sprung the day after tomorrow.”

“That’s fine,” smiles the big chief. “They is causing us a lotta trouble. ‘

“Unwrinkle your brow, gov,” I cuts in. “My golf bill will solve everything.”

“I must look into it,” says he, and me and Cravens beats it.

“I thought,” remarks Luke, “that you canned that tax idea of yourn when the Doughmorons started being for it.”

“No,” I tells him, “I’m going through with it just to prove to them coupon barbers that they give me the wrong rap.”

“Well,” says Cravens, looking at me kinda narrow, “the play might work out good for you at that.”

“You mean,” I asks, “the bill might pass?”

“It’s got as much chance of doing that,” he answers, “as one of them ducks of yourn would have in a scrap with three wildcats, four hyenas and a pair of Australian gluffaws.”

“I don’t get you,” I returns, puzzled.

“No?” smiles Luke. “All right, Rollo, roll your own hoop. If you should want me to cut in later on, you knows where to find me.”

I’m still all up in the air trying to figure out what Cravens’s been driving at when I gets to the hotel by myselfs and runs into Shem Conover, a baby from up in the state that was knocked down to me earlier in the day as a real slicker in jamming stuff through the House.

“I been waiting to see you,” says he. “I wanna little chin-chin.”

“About which?” I inquires.

“That golf-tax bill you’re touting,” he answers. “Need any help?”

“I ain’t so sure I’m going through with it,” I tells him, not liking the bimbo’s looks.

“Who’s been talking to you?” he asks, slipping me the narrow eye like Cravens done.

“What you getting at?” I yelps, getting kinda peeved at the mystery stuff.

“Listen, bo,” says Conover, “and don’t try and gruff me off the lay. If you wanna get any action with that bill of yourn you gotta be sweet to me. I’m chairman of the committee that’s gonna get it, and if you don’t put me in the line-up — ”

“What’ll you do?” I barks.

“I’ll fix it,” he comes back, slow, “so that the chloroform won’t work when you want it to, and when you gets ready to deliver the body you’ll find the livest corpse you ever seen.’

“I’ll sue the Central for this,” says I. “When a lad buys a ducat for Albany they ain’t got no right to dump him off at Matteawan.”

“You’re in Albany, little one,” remarks Conover, cold; “and when you is in Albany you gotta do like the Albanians does. Do I get a hand dealt me?”

“I ain’t gonna introduce the bill,” I growls, “and besides — ”

“Too late,” interrupts Shem. “If you run out on it I’ll have it introduced as a committee measure. The idea’s too cushy to drop. They worked it with patent medicine down in Arkansas and with baking powder out in Missouri, but the golf act’s a new one on the sandbag circuit. Give it a coupla thinks,” he finishes up, and drifts away casual.

I looks around expecting a guy in blue with a bunch of keys to grab him, but nothing like that don’t happen. Dizzy and woozy, I drifts across the street to the restaurant Luke told me about and squats me down.

“What’ll you have?” asks the waiter.

“A cup of tea, God forbid,” says I.

It’s wonderful what a little oolong will do for a lad that gets the kind he means instead of the sort he asks for, and right away I begins to perk up some. But it don’t last long. I’m about to yell for an encore when I looks up to see a feller standing besides me, a stout, surtaxy appearing citizen with a wide grin.

“Know who I am?” he inquires.

“Considering the luck I been in all day,” I answers, “you couldn’t be nothing excepting a revenue agent.”

“My card, Mr. O’Day,” says he, and slips it.

“‘August P. Stevens,’” I reads aloud, and then to myselfs, “‘representing the Universal Outdoor Co.’”

“You cover all that territory by yourselfs?” I asks.

“No,” he comes back; “I’m mostly in Albany and Washington.”

“What do you sell,” I wants to know, “scenery or air?”

“I don’t sell,” he returns, looking me straight in the eyes. “I buy.”

“What?” I asks.

“Different things,” he answers, evasive. “I suppose you know we is one of the largest sporting-goods houses in the world. Naturally, we is interested in your bill to tax golf balls and sticks. Shall I sit down?”

“If your lumbago’ll let you,” I replies; “but you might as well know later than sooner that I’ve heard enough of that bill this afternoon to last me until three weeks after my funeral. I ain’t even sure I’m gonna flip it into the hopper.”

“The boys around here,” says Stevens, “’ll tell you that I’m a square shooter and don’t mince up no words. With me a spade’s a spade and I know how to dig. What do you need to help you make up your mind about that bill?”

“Which way?” I mumbles, fanning for time.

What a zero brain I’d been not to get jerry to that talk of Luke and Conover about sandbags and chloroform and the such!

“Our way, of course,” answers the sportsgoods man. “You forget the golf tax and we’ll not forget you.”

“I see,” says I; “you wanna bribe me not to put the bill in.”

“Oh,” returns Stevens, “you can put it in; but it’ll get sick in the committee room, be operated on and die under the ether. All you gotta do is to let the dead stay dead and get all wound up in something else. You ain’t got a thing to lose. They ain’t no chance of jamming the tax over and — ”

“What do you wanna buy me off for then?” I cuts in.

“Well,” says Stevens, “they is always a outside possibility of anything going through in the last-minute rush. Besides, we don’t wanna have taxes on balls and clubs even discussed.”

“You can’t stop that,” I retorts. “I’m full of it now.”

“Full of what?” he inquires.

“Disgust,” I snaps, and ducks outta the place.

IV

They ain’t no meeting of the legislature the next day, and I runs down to Doughmore, first having wired Cravens that I was coming and for him to meet me. I ain’t one of them holier than thous, but raw work always did get me sore, even in them times when I didn’t ask a dollar bill for references. Luke sees right off that I’m riled.

“Do I look like a grafter?” I asks.

“The light ain’t so good here,” he comes, back, calm. “What makes you doubtful?

I cuts loose and tells him everything that happened to me in Albany after he left. He listens with about as much excitement as I was retailing a bright crack pulled by my third cousin’s infant progeny.

“You don’t seem surprised none,” I remarks at the finish. “Is they all dips up in Albany?”

“No,” replies Luke, “they is about 95 percent honest; but at every session in every legislature they is always a few sandbaggers — guys that push in stick-up bills, not with any hopes of passing ’em, but on it gamble that somebody will get all scared up and buy ’em off. The railroads used to be the prize marks, but — ”

“Say,” I shoots out a yelp, “you ain’t got no ideas that I’m a sandbagger, is you?”

“Well,” returns Cravens, “at first I thought that blah of yours about golf and ducks was just some pretty fun you was having with the Doughmorons; but when it flopped with them and you kept right on yelling tax, even in front of the governor, I begun to get a little suspicious.”

“Honey sweets the Malay’s pants!” I hollers.

“Huh?” inquires Luke.

“That’s Latin,” I explains, “for lads with evil minds that thinks everybody else is got ’em.”

“Evil mind, eh?” says Cravens, kinda peevish. “Any bird that’ll go to the front for a new nuisance tax, when everybody in the country is nearly bent over double carrying the load of ’em they got now is either a stupe or a grafter. And you ain’t so stupish.’

“Damn it,” I barks, “I’ll — ”

“Listen to me,” interrupts Luke. “I ain’t calling you a crook, but what do you expect people’ll think of a bobo in these times that’ll talk up another gouge, and picks out a nice juicy game like golf for the victim?”

“I was only kidding,” I mumbles, feeble;

“I suppose,” admits the chairman; “but like the feller remarked after lugging careless baby six blocks, they is such a thing as carrying a kid too far.”

“It seems to me,” says I, suddenly remembering his stuff in Albany, “you was willing to take your bit.”

“I was,” he answers, cool, “I don’t never throw no spoons away when it’s raining soup.”

“Gosh,” I groans, “I’m in a swell fix. If I don’t introduce that bill now they’ll say I been bought off. If I does, I’ll have to go to the mat for it and keep fighting all the time I’m gonna resign,” I announces, blunt.

“That’ll be the worst yet,” says Cravens “Then they’ll figure you was bought off good and was afraid of a investigation.”

“What shall I do?” I asks.

“Just forget all about it,” advises Luke. “I’ll fix things with Stevens and Conover so nothing’ll ever be mentioned about the golf bill.”

“Sure you can?” I wants to know.

“Certain sure,” says Cravens. “Won’ I the guy that sent ’em to see you?

On the way to the house I meets up with Lizzie. “I just been to the Monday Club,” she tells me. “You still wanna hire a hall?”

“No,” I answers, “not a hall — a hole.”

“A hole?” repeats Lizzie. “What you gonna do with a hole?”

“Crawl in,” says I.

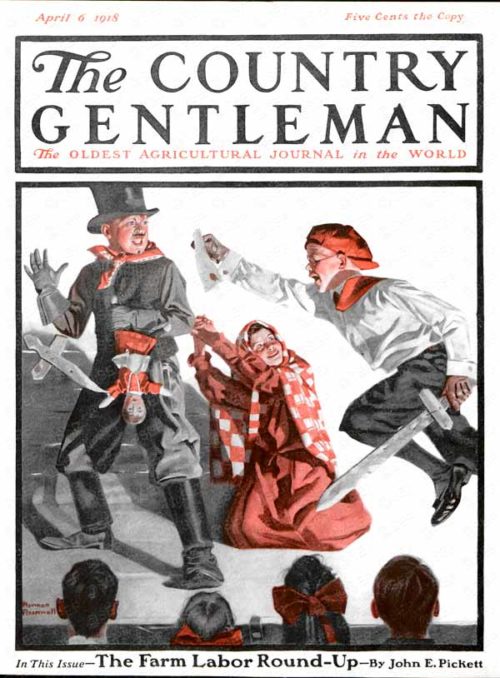

Featured image: “Flying codfish! And you’re the kinda guy that’s gonna make laws for fifteen million people!” (Illustrated by Tony Sarg)

“Home-Brew” by Grace Sartwell Mason

With more than 80 short stories and eight novels, Grace Sartwell Mason’s thematically diverse work found many publications in the period before and after World War I. Though her fiction and criticism has slipped through the cracks of familiarity over the years, her story “Home-Brew,” about the secretive and adventurous family of a budding New York writer, was an O. Henry Award finalist.

Published on August 18, 1923

Content Warning: Racial slurs

“Of course, they’re all dears, my family,” said Alyse; “but as fiction material there is nothing to them; no drama, you know; no color; just nice, ordinary, unimaginative dears. They’re utterly unstimulating. That’s why I can’t live at home, and create. They don’t understand it, poor dears; but what could I possibly find to write about at home?”

She crushed down upon her hair, with its Russian bob, a sad-colored hat of hand-woven stuff, and locked the door of a somewhat crumby room over the Rossetti Hand-Loom Shop, where she worked half time for a half living. A secondhand typewriter accounted for the other half; or, to be quite truthful, for a fraction of the other half. For her father, plain George Todd, helped out when the typewriter failed to provide.

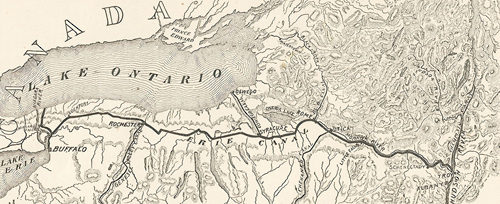

She then betook herself on somewhat reluctant feet to the nearest Subway. For this was her evening at home with her unstimulating family; and though she was fond of them all, her predominating feeling for them was a mixture of amusement, tender tolerance and boredom. Moreover, they lived in Harlem, which was a deplorable wilderness, utterly lacking in atmosphere and a long, long way from the neighborhood of the hand-loom shop.

In the Subway, miraculously impelled through the bowels of the earth, Alyse — or Alice, as she had been christened — refrained from looking at the faces opposite her. The Subway does something curious to faces. It seems to drain all life out of them; it strips from them their defensive masks and exposes the deep and expressive scars of existence. A secret and hidden soul comes out in each Subway face. But Alyse averted her eyes.

“Dear me,” she sighed, “how dull they are! Isn’t there any beauty left in the world?”

Her father and his chum, Wally, were just ahead of her as she came up from the Subway depths. They were wending their way to their respective homes, having come up from downtown together, as was their invariable custom. Alyse gazed at their middle-aged backs without seeing anything unusual about them. Just two plodding men, getting tubby about the waist, with evening papers under their arms, walking along, not saying much. But when they reached George Todd’s door they would look at each other, and the passerby might well have stopped and taken off his hat, as before something rare and soul-satisfying. For here was perfect peace in friendship.

But all they said was: “S’long. See you tonight, ol’ hoss.” Or, “See you t’morrow mornin’, Georgie.”

Alyse had heard the tale of her father’s miraculous reunion with Wally so many times that it meant nothing to her. It seemed that as boys they had lived within two doors of each other in a small New England town, and they had been inseparable. First thing in the morning and last thing at night they were whistling outside each other’s windows; they owned a dog in common; and when George had scarlet fever, Wally nearly died from anxiety. Then, at sixteen, life had borne them in different directions. Wally drifted finally to Alaska and George got a job in New York. For a time they corresponded, but after a while letters began to come back to George marked Not Found, and then in a roundabout way he heard of Wally’s death.

Although George Todd was happily married, with a growing family, he admitted that the world would never seem quite the same to him with Wally out of it. Then came the happening that convinced him there are mysterious and unexplainable things in the world, say what you like. He was coming home from work one night, walking from the Subway rather more slowly than usual and enjoying the spring twilight, when in some strange way his heart stirred. He remembered how on evenings such as this he and Wally used to play a game in which one tossed a ball over the house to the other and gave a peculiar call. The middle-aged George declared that all of a sudden he could hear this call, and wanting to fix it in his memory, he endeavored to imitate it by whistling its rather melancholy intervals.

And at his whistle a man walking in front of him suddenly whirled and stared at him. It was Wally — Wally, with a newspaper in his pocket and a bundle of shirts from the laundry under his arm. He had been living within half a block of George for two years.

When her father told this story to Alyse he always at this point gave her an affectionate poke.

“Now there’s a story for you, Allie. You write up about Wally being washed out to sea and given up for dead and working his way around the world, and finally settling down in Harlem right next door to his old chum. And that about the whistle. What was it made me think of that old call?”

Alyse would explain that it was coincidence, and coincidence was the lowest form of literary life. She was patient about it, but there was nothing stimulating to her creative imagination in Wally and that come-and-find-me voice he had listened to half his life. Still less was she stimulated by her father, George Todd, owner of a feed and grain business of the most eccentric instability. He was a dear, and she loved him; but she hoped as they all sat down to supper that he wouldn’t begin to joke her about her work or offer her the plot for a story.

It was a spring evening and the dining room windows were open to the two lilac bushes which Alyse’s mother had nursed for years in the narrow, sooty backyard. The room was filled with an unreal light, as if the air was full of golden pollen dust. And something else, invisible and palpitant, was in the air of the homely room, something not to be seen but only sensed. Some intense preoccupation a sympathetic eye could have noted in three of the faces around the table.

“Well, well, we’re all dressed up tonight,” said George Todd, unfolding his napkin. “Look at Miggsy, Allie. Won’t she knock somebody’s eye out tonight?”

Alyse looked at her young sister, Mildred, aged sixteen. Mildred blushed, fidgeted, pouted entreatingly at her father. She was a thin little beauty, with a soft cloud of corn-silk hair about her face. In her red mouth desire and wistfulness mingled. Tonight her eyes were stretched and brilliant. She twitched at the table silver and appeared to have no appetite.

“Eat your spinach, dearie.” Her mother’s eyes brooded over her tenderly. “I thought you liked it creamed.”

“I do, but — Goodness, mother, is that clock right? I must fly!”

“But there’s chocolate pudding for dessert, dear.”

“Now, Miggs, finish your dinner. Why be so fidgety?”

Mildred looked in desperation from her father to her mother.

“But I don’t want any dinner, please! I — I have to be there early. Please let me go now, mother.”

She danced from one foot to the other, the secret excitement in her eyes threatening to change to anger. She had spent most of the time since she came home from school that afternoon in front of her mirror, and she was now exquisitely polished, powdered and perfumed. From under the fluff of hair over each ear an earring of blue to match her eyes dangled.

Alyse disapproved of the earrings and of the general effect of Milly tonight. She made a mental note to speak to her mother about letting the child go out so many evenings. But beyond the earrings and the general overstrung and overdressed effect she did not penetrate. She made no attempt to interpret the secret excitement in her young sister’s eyes. The affairs of a girl of sixteen were too inane and foolish to be taken seriously.

At the table when Milly had gone flying up the stairs there remained Alyse, her father and mother, Eddie, twenty-one, and Aunt Jude. Alyse glanced around the table and suppressed a sigh. The monotony of the lives of her family sometimes oppressed her. Take her mother, for instance. She seldom went outside the house except to church or to an occasional motion picture with Wally and George. All day she did housework or looked after Grandma Todd when Aunt Jude was at work. She did not have a cook because of a queer passion for feeding her family herself. But when she had them all there in front of her, ranged around the long table, and she had put onto their plates the well-cooked, savory dishes they liked, she would sit, eating little herself, looking from one to the other with her slightly anxious, tender glances, while gradually an expression of peace and satisfaction stole into her face; and Alyse wondered what her mother was getting out of life.

Take Eddie, also. No one, except perhaps his mother in odd moments, ever got a peep-in at Eddie’s thoughts. Alyse was of the opinion that he didn’t have any. There had been a time when she had tried to bring Eddie out by coaxing him down to her rooms over the hand-loom shop and introducing him to some of the girls she knew. But those clever and voluble maidens had abashed Eddie unspeakably, and Alyse had let him lapse back into his own plodding life. He apparently had no imagination. Soon after he left high school he had gone to work for a seed house downtown — George Todd badly needing help that year with the family expenses — and there he still was. Alyse hadn’t the slightest idea what were his amusements. Saturday and Sunday afternoons he generally disappeared, and when asked what he had been doing, he had been to a ball game or just taking a stroll around. He subscribed to a marine journal, which seemed strange reading for a packer in a seed house.

Take Eddie, also. No one, except perhaps his mother in odd moments, ever got a peep-in at Eddie’s thoughts. Alyse was of the opinion that he didn’t have any. There had been a time when she had tried to bring Eddie out by coaxing him down to her rooms over the hand-loom shop and introducing him to some of the girls she knew. But those clever and voluble maidens had abashed Eddie unspeakably, and Alyse had let him lapse back into his own plodding life. He apparently had no imagination. Soon after he left high school he had gone to work for a seed house downtown — George Todd badly needing help that year with the family expenses — and there he still was. Alyse hadn’t the slightest idea what were his amusements. Saturday and Sunday afternoons he generally disappeared, and when asked what he had been doing, he had been to a ball game or just taking a stroll around. He subscribed to a marine journal, which seemed strange reading for a packer in a seed house.

And there was Aunt Jude. Really, when you considered everything, what had Aunt Jude to live for?

Judith Todd was at that moment preparing a tray for Grandma Todd, who was having one of her faint spells and declined to come down to supper. With her long, slender fingers moving deftly, Judith made the tray inviting with the china she had bought especially for it. She had hurried her own supper so as to have plenty of time for the tray, and she moved from the table to the sideboard with the air of detached and ironic competence she sometimes wore when she was, as Alyse said, spoiling Grandma Todd. She was George Todd’s younger sister, thirty-eight, a spinster with the reputation of having been in her youth very high-spirited, adventure-loving, and moreover with a streak of queerness about her. As, for instance, her ambition to be a sculptor. In those days and in the Todds’ native village a girl might as becomingly have wanted to be a circus rider. It was said there had been some stormy scenes over days wasted in the attic with messy clay. But finally life itself had put a bit between her teeth — life and her mother’s well-timed heart attacks. Her father had failed in business and died, George had married early, and the brunt of taking care of her mother had fallen to Judith.

After a while she had brought her mother to George’s house, which helped George out with expenses and enabled Judith to make a living for herself. It was the nature of her job that convinced Alyse there couldn’t be anything in that old story about Aunt Jude’s having wanted to be an artist. It was such an absurd job. She worked for one of those concerns that produce novelties — favors, table decorations, boudoir dolls — designing many of these silly fripperies, often making them with her own hands. She had remarkable hands.

If she had an ounce of talent, Alyse decided, how could Aunt Jude go on, year after year, squandering herself on these silly and often grotesque objects? Alyse felt that it would have killed her to have so degraded her talent.

But Judith actually appeared to get a certain amount of fun out of the dreadful things. She would bring home samples of her handicraft and bedeck the supper table with tiny fat dolls in wedding veils, droll birds and beasts in colored wax, and so on. And in one of her high moods she could set the family to laughing with a single tweak at one of these grotesqueries. On these occasions a gay and malicious sparkle would come into her dark eyes, and her laugh would be high and reckless, rather like a person who has taken a stiff drink to ease up an ancient misery.

Two evenings a week she went out, no one knew where. Alyse had seen her once at the opera, leaning far out from the highest gallery, a frown between her brows, seeming to watch rather than to listen, with a wild brightness in her dark eyes. The general impression of the family was that these regular evenings away from home had something to do with her work. On these particular evenings there was always a breathless air about her. She would hasten in from the street, and as she climbed the stairs to her mother’s room her face would stiffen as if for conflict. For Grandma Todd resented these evenings.

“Traipsin’ off,” she called it. “Lord knows where. Something will happen to you, coming home alone after ten o’clock. I don’t think you’d better go out tonight, Judith. My heart has been fluttering this afternoon. If I have to lie here worrying all evening I shall probably have a bad spell.”

And then into her daughter’s face would come the expression of a person swimming painfully against the tide. Love and pity had overcome her at every turn of her life, until at last she had almost nothing of herself left, except her freedom for these two evenings. As if the call of them was more imperative even than her long habit of abnegation, she fought for them with a sort of desperation.

Tonight as she arranged her mother’s tray her fine hands trembled a little; she looked more than ever as if she were straining at a leash. There was an unusual color in her face, a sort of flame, which for an instant attracted Alyse’s attention. Aunt Jude, she reflected, must have been almost beautiful when she was younger, before the expression of half-defiant endurance came into her face. Her dark hair was still lovely, with its blue-black shadows. Over her brow was a white lock, which she took no pains to conceal. She wore it rather like a defiant banner, and it went well with a certain gallant air she sometimes had.

As soon as supper was finished the family began to melt away. Wally called for George Todd and they went out. They admitted, grinning, that they were going to an express-company auction of unclaimed packages. It was one of their pet forms of entertainment, and they frequently brought home queer bundles, which they opened with shouts of amusement. Alyse thought they were dears, but rather foolish. She could not guess that when they started out of an evening arm in arm they became boys again, and forgot that life had been a somewhat niggardly affair for them.

A moment later Miggs made a dash for the door, pulling on her long gloves. Her face was flushed and exquisite under her modish hat.

“I’ll have Eddie come around to Jane’s for you, Milly,” her mother called to her.

A shadow of fright and annoyance came over Miggs’ face.

“No, please don’t, mamma. Jane, or somebody, will come home with me. Besides, we — we may go to a movie. Don’t fuss over me, mamma. I’m not a baby.”

Then she darted back into the room, caught her mother’s head in her slim arms, snuggled her little powdered nose into her neck.

“Oh, mamma, I’m all right. I’m just so full of pep tonight I’m — I’m snappy. Don’t you worry, darling.”

And licking her scarlet lips, glancing once more into the mirror of the old-fashioned sideboard, she was off — a hummingbird caught in a mysterious gale.

Then appeared Aunt Jude, her jacket over her arm, the tray in her hands. Her dark eyes were feverishly bright, but her face looked pale and strained. Would they mind just cocking an ear now and then toward mother’s room? She would probably drop off to sleep soon, though she had made up her mind she wouldn’t.

“But I must go tonight,” she said; “just tonight. Perhaps after this I — won’t be going out Tuesday and Thursday evenings.”

She stood still, staring down at the tray she had put on the kitchen table. Then she threw up her head with the familiar defiant movement, made a sound as if of scorn at her own weakness, and shrugging herself into her old blue serge jacket, she, too, darted out into the evening.

Eddie stood by the window. He stooped to look up at the dark blue of the night sky — a gesture habitual with him — fiddled wistfully for a long moment with the shade, and then pulled it down as if resolutely shutting something out. But a moment or two later he took his hat down from the hall rack, muttered to his mother “Be back early,” and slid out the front door, as if suddenly afraid of being late for something.

The house fell silent. Alyse’s mother put a dark-red spread on the dining-room table and placed her darning basket under the light.

“Now this is cozy,” she said happily. “We’ll have time for a nice visit. Tell me about your work, dear. I’ve been hoping maybe you’d feel like coming home to stay as soon as you’d got some material to work on. Of course, I understand,” she added humbly, “you have to have something to inspire you.”

“That’s exactly it, mother. I must know interesting persons. It’s very important to be stimulated. Sometimes I’ve thought that if I could only go to Russia or Austria or some place where there is a sense of crisis, a — a vividness, you know; strife of souls. That’s what I want to study. You see, mother? And, of course, here at home — ”

Her mother sighed.

“I know we’re all pretty ordinary, and nothing much happens, here at home.”

She looked apologetic, as if she realized the family’s limitations and wished she could offer something more interesting to her talented daughter. She dropped the old darning egg into the heel of a sock. The homely house was very quiet.

And a few miles farther south Milly was running breathlessly up the Subway stairs, an eager, half-frightened Proserpine coming up from the bowels of the earth into flowery meadows, into the glare of the electric flowers of Broadway.

And a few blocks north Judith Todd stood in a dark doorway and whispered: “I mustn’t hope for anything. If nothing comes of tonight, I can go on. But, O, God, make something come out right for me at last, at last!”

And Eddie —

At about this moment Eddie’s mother was rolling a pair of his socks into a neat ball. She sighed unconsciously.

“Sometimes it seems to me,” she said, “as if Eddie has never really waked up. I can’t express it the way you would, Alice; but as if he was driving himself — dumb, you know.”

“Doesn’t he like his job?”

“I don’t know. He never says. But sometimes he looks — And then there’s that Haskins girl. I’m afraid he’s let her push him into being engaged. I wish I knew — he’s so silent lately … When he was a little boy he used to lie on the floor by the hour, so happy, drawing pictures of ships.”

Ships! Alyse had never noticed them, but they lay like a fringe about the tall city, slowly rising and falling with the tide, lying there waiting to be unloosed to the seven seas. But Eddie knew they were there. All the miles of wharves he knew, from Sunday and evening rambles, from noon hours when he went without food to stand looking at some lovely visitor from an unknown port. And now at this moment he was making his way as fast as he could to say farewell to one that had become the very core of his heart.

More eagerly and more swiftly than he ever had made his way to the Haskins girl he traveled toward the North River. Just before he reached the corner beyond which he could look down upon the river he felt his heart grow cold with the fear that sometime during the day she may have slipped out to sea. It seemed to him that if she had gone he could not bear it; and yet he told himself that tomorrow night she would not be there; they had begun to ship her cargo.

But when he had rounded the corner, there were her masts against the deep blue of the night sky — five masts, the beauty! He had seen them two weeks before one night when he was leaning over the wall of Riverside Drive, and his heart had leaped. He had made his way down to the wharf alongside which the schooner lay, and stood there studying her, feasting his eyes on her. The tall cliffs of houses towered above her, but she smelled of many cargoes and of the sea. He could imagine her furled canvas slowly shaking out to the breeze, the deck tilting. The mate had come up on deck with his pipe and talked to him over the side.

Next evening Eddie was there again, and the mate invited him on board; he talked about the schooner as a man might about a wife whose very faults he loved. And Eddie had asked him questions which had been storing up in his heart since he was a boy. He could talk to this man Jennings, for they had a passion in common. Evening after evening they leaned over the deck rail or sat in the cabin, smoking and talking, and a deep friendliness developed between them.

Tonight when Eddie came to the edge of the Drive he did not hurry down as usual to the wharf where the schooner was tied up, but stood looking down at her. In his brain there was a misery and a battle. They were working overtime down there, loading the last of a general cargo, and that meant they would take advantage of the first tide. Tomorrow she would be gone, off to the River Plate. He shut his eyes hard and gripped the wall against which he leaned.

Tomorrow he would go downtown as usual in the Subway, and all day long he would be nailing up boxes in the basement of the store, and in the evening he would go around to see Lily Haskins. Under his breath he uttered a sound between a groan and an oath. He felt bewildered when he thought of Lily. He gazed at the five masts against the sky and they were like a shining vision beside which Lily Haskins was but a dull unreality. Was it actually true that he was going to marry, to go on all his life nailing up boxes as if they were his own coffin?

His feet carried him slowly down toward the wharf. He must say goodbye to Jennings, no matter how much he shrank from going on board the schooner again, and as he went down the long stairs he was wondering at the stupidity of his own life. Why hadn’t he talked things over with someone? Perhaps someone else could have told him whether he was really obliged to marry Lily. But he guessed that he had always been dumb. Life had gone on within him, half alseep, in the dust of the packing room, until he and Jennings and the schooner became friends.

And after that he had awakened, but he was still dumb. Perhaps if years ago he had begun to talk about what he wanted to do — But that year when he was eighteen, and making his secret plan to join the Navy, was the year dad’s business was so poor. He couldn’t desert him when he was so hard pressed. Perhaps later, when dad had got on his feet, he might have broken loose, if only he had believed in his dream; if he hadn’t been afraid of being laughed at.

His thoughts went still farther back, to the days when he used to cover immense sheets of paper with pictures of ships, full-rigged, with each detail as correct as he could make it from pictures he had seen.

He remembered looking up one day from his drawing with a sudden vision in his heart and crying out, “When I grow up I’m going to be a sailor!”

And someone, he could not remember who, had laughed. For a long time they called him Yeave-Ho. The door of his heart through which this cry had gone out had closed.

If he had cared less about his dream, the door would not have closed so tightly, perhaps; or if there had been anyone in his world who did not regard the sea as merely a blue blur in a geography.