Theresa Helburn, of the prestigious Theatre Guild group, was seeking just $35,000 more to stage a musical version of Lynn Riggs’s Green Grow the Lilacs in 1942, but it was difficult to convince investors to fund the project. More than 50 people turned her down, possibly because of the group’s failed production of the straight play in 1931. Helburn and her partner Lawrence Langner drummed up the necessary support, however, and opened the musical Away We Go for previews in New Haven, Connecticut.

After some changes to Away We Go — songs were shuffled and unruly onstage pigeons were nixed — the musical in its final form, Oklahoma!, opened 75 years ago on Broadway. The naysayers of the New York theater crowd didn’t just underestimate the show’s potential; they passed up the opportunity to take part in the first Broadway musical smash hit.

Public interest in the show grew exponentially after its Broadway premiere, leading one radio announcer to quip, “Look at that play Oklahoma! A man died last week and left his place in line to his wife. If she dies before she gets her tickets, her place in line goes to an uncle in Baltimore.” Reportedly, the $4.80 tickets were going for as much as $50 on the street.

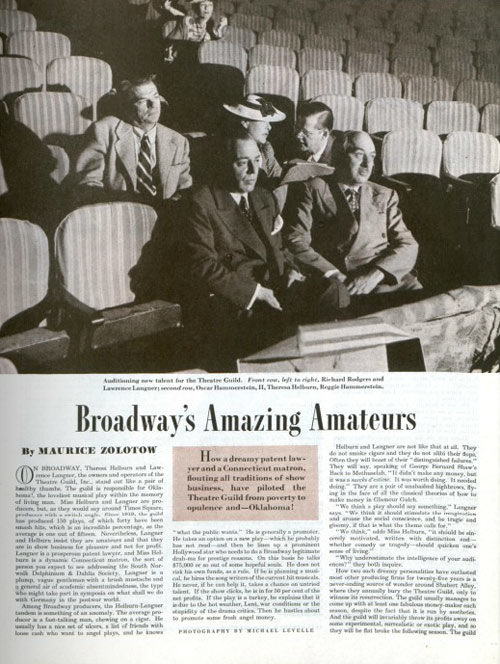

The folksy musical was the first collaboration between composer Richard Rodgers and lyricist Oscar Hammerstein II. It was also among the first ever musicals, as we typically know them today. Oklahoma! told an ambitious story coherently using lyrics, dance, dialogue, and music — a form considered a “book musical.”

Rodgers and Hammerstein would go on to rule Broadway in the postwar years with their saccharine portrayals of romance and morality like South Pacific, The King and I, and The Sound of Music. Stephen Holden wrote of the duo, in The New York Times: “The America of Rodgers and Hammerstein — where the good guys won, love conquered all and progress was taken for granted — was itself a dream, a golden bubble of postwar hope and confidence that evaporated more than it burst.” Before it dissipated, however, the Rodgers and Hammerstein machine altered musical theater, and perhaps all music, for good.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Really good feature Nicholas. I didn’t even think about ‘Oklahoma’ having had origins before the 1955 film, but of course it had to. I really have to thank my parents for taking me to the theater to see re-releases of ‘Oklahoma’, ‘The King and I’ and ‘The Music Man’ to cite 3 examples.

In 1965 at 8, I was old enough to remember ‘The Sound of Music’ when it was new. As a teenager my taste in musicals had changed to rock operas almost exclusively by 1975 when ‘Tommy’ (starring Ann-Margret) came out just a few months after ‘Phantom of the Paradise’. I’d seen both in the theater at the time with friends.

I unwisely tried to return the favor taking my folks to see ‘Tommy’. They didn’t see it as “brilliant and wonderful” as I did, at all. They were in fact upset with the ‘What About the Boy?’ scene and faith healing (Eric Clapton) scene with the large ceramic figure of Marilyn eventually crashing to name two.

Today I still love rock operas, but no more so than the brilliant ‘Oklahoma’ and ‘The Sound of Music’. Both are a kind of antidote to the ugly world we live in now. Some of the seeming silliness in the earlier parts of ‘The Sound of Music’ was a type of antidote to the horrors of World War II that would lie ahead for this family, eventually having them all running for their lives at the end of the film.