The Conspiracy Theory That Spawned a Political Party

Good, Christian American families were whipped into a hysteria over a shadowy, secretive — and possibly even satanic — cabal subverting our nation’s democracy, conspiring against justice, and performing bizarre, blasphemous rituals.

This may sound like a modern, paranoid movement on social media, but it’s actually describing a 200-year-old conspiracy theory in the U.S. that alleged that men in the growing Freemasonry fraternity were engaged in a nefarious plot to exert unchecked control over the republic. The Anti-Masonry movement grew to become the first “third party” in the country’s history, permanently altering American politics during a transformative political realignment that would see new parties, ideals, and democratization of the U.S. system.

The spread of Anti-Masonry and its attendant conspiracy theories were aided by the simultaneous religious revivals sweeping across the states, and the movement’s transference into the political sphere met with other opponents of Andrew Jackson. But an important aspect of this conspiracy theory has often been overlooked: it began in reaction to an actual conspiracy.

No other modern historian has spent as much time digging into the history of Anti-Masonry as Kathleen Smith Kutolowski. Born and raised in a small town in Genessee County, New York, she collected otherwise untouched Masonic data from the region, offering a more complete picture of 1820s New York and demystifying the period of supposed hysteria.

Kutolowski’s father belonged to a Masonic lodge. When she began writing her dissertation on the general political development of the area in the 19th century, she says, “I kept running into Masons as political leaders, right down to candidates for county coroner.” She analyzed the records of Genessee and nearby counties and found that Masons were not necessarily the upper-class elites that many had thought; they came from a variety of backgrounds, economic statuses, and denominations.

This was in line with her discovery that there were many more Masonic lodges in Western New York than anyone else had cared to document.“Masonry was a more widespread phenomenon than people understand, and they dominated political office,” she says.

In the 1820s, Freemasonry enjoyed explosive growth in cities, towns, and even small villages in the Northeast. Tens of thousands of Masons had established hundreds of lodges in states like New York, Massachusetts, and Connecticut, and they held “influential civic positions out of proportion to their numbers,” according to Kutolowski’s research. Many of the founding fathers, including George Washington and Benjamin Franklin, had been Masons. In New York especially, Masons held power. But the popular movement against them arose because of the ways they wielded it, particularly in Genessee County in 1826.

That summer, a man named William Morgan announced his plans to publish a sort of Freemasonry tell-all with the Batavia Republican Advocate publisher David Miller. Morgan had attended some local Masonic meetings and claimed to be a longtime member, although the latter was unsubstantiated. His exposé was to be called Illustrations of Masonry, and the Masons at the Batavia lodge became obsessed with stopping him.

They began to harass Morgan and Miller. The sheriff of Genessee County, a Mason, complied with his fraternity and arrested Morgan several times on petty debt charges. Another gang of Masons attempted to ransack and set fire to Miller’s offices. In September, Morgan was sitting in jail in Canandaigua when a stranger bailed him out. Upon release, the writer was ambushed by several Masons and forced into a closed carriage. They drove him to Fort Niagara, and he was never seen again.

Most historical analysis of Anti-Masonry focuses on Morgan’s disappearance as a fairly simple explanation for the birth of the movement, but Kutolowski explored the circumstances around the incident more thoroughly, saying, “The important event was not necessarily the kidnapping itself, but the cover-up that followed.”

Though Morgan’s kidnapping and (likely) murder were an outrage, the Masonic subterfuge that was to come would only exacerbate any extant public perceptions that the fraternity posed a legitimate threat to freedom.

For more than four years, trials and grand jury investigations kept the “Morgan Excitement” in the news and on Americans’ lips. Dozens of Masons were eventually indicted, but not without obstruction from Freemason police officers, politicians, lawyers, doctors, and clergy. Once-Mason and well-regarded New York publisher William Leete Stone thoroughly documented every moment of the Morgan affair at the time in his Letters on Masonry and Anti-Masonry … , maintaining that “the men engaged in this foul conspiracy, thus terminating in a deed of blood, belonged to the society of Freemasons.” Stone tracked the indignant public protest and subsequent legal action over Morgan’s disappearance, but, as he wrote, “they soon found their investigations embarrassed, by Freemasons, in every way that ingenuity could devise.” In the Genessee grand jury trials of 1826-27, five of the six foremen were Masons, including one who was implicated in the scandal. The juries — picked by sheriffs at the time — were full of Masons, or their brothers or sons, and the few Masons who spoke out against the fraternity’s militant protection of its own were expelled from their lodge. Similar circumstances stalled or obstructed justice in Ontario County trials as well.

While the obvious perpetuation of injustice at the hands of Masons generated plenty of reasonable Anti-Masonic sentiment, the more fervent among the movement spun irresistibly fascinating webs of accusations against the fraternity. Kutolowski says that “protest did not leap full-blown from the kidnapping to beliefs about Satanic conspiracies,” but a market for the latter seemed to open up nonetheless.

Morgan’s manuscript was published a few months after his disappearance, and, while it offered an abundance of detail on Masonic practices, the book failed to live up to its sensational promise as “a master key to the secrets of Masonry.” It was soon eclipsed by legions of articles, books, speeches, and entire Anti-Masonic periodicals that disclosed — often fallacious — claims regarding the fraternity’s evils.

In Danville, Vermont, the local paper North Star (not to be confused with Frederick Douglass’s publication of the same name) published a message from the Genessee Baptist Convention in 1828: “That Free Masonry is an evil, we have incontrovertible proof; and this appears from its ceremonies, its principles, and its obligations.” A few months later, the Star reprinted (from Morristown, New Jersey’s Palladium of Liberty) one Mason’s “renunciation” from Freemasonry, colorfully painting the fraternity’s membership as men “whose hands reek with the blood of human victims offered in sacrifice to devils, or who worships a Crocodile, a Cat or an Ox.” Such dramatic renunciations by supposed ex-Masons were regular fixtures in Anti-Masonic papers, and lists bearing the names and towns of recent Masonic renouncers often accompanied them.

An 1831 issue of Vermont’s Middlebury Free Press featured a fictionalized dialogue between the mythic demons Belphagor and Beelzebub in which they boast of their Satanic sway over Freemasonry (“That bulwark of our empire on earth!”) and delight in their ungodly machinations against the republic (“ — that post, well-fortified, in our enemy’s country, from whence, at pleasure, we may make successful inroads upon his friends and people!”) .

Anti-Masonic fervor wasn’t contained to printed communications; it manifested in real-world violence as well. Though Freemasons had traditionally marched in annual St. John’s Day parades, their celebration in Genessee County in 1829 was met with Anti-Masons who threw rocks at them. Then, protesters ransacked a Royal Arch Chapter headquarters. Freemasons were spooked — particularly those in Genessee County, where 16 of the 17 lodges and two chapters soon dissolved. But for many Anti-Masons, public renunciations and even dissolution of local Masonic charters was not enough. They held that Freemasonry must be abolished, that its mere existence — even if it was weakened and relegated to the shadows — was proof that their work was yet unfinished. Wilkes-Barre’s Anti-Masonic Advocate expressed as much in 1832: “To overcome this evil is a work of intelligence, and a work of time. We have scotched the snake, not killed it. We have forced it to hide in darkness — but though unseen, it is not less dangerous.”

Anti-Masonry’s entrance into electoral politics was swift: the spring after Morgan’s kidnapping saw Anti-Masonic candidates for office in Genessee County. “Their level of organization was amazing,” Kutolowski says, “right down to school district committees, taking a social issue to the ballot box.” Since Anti-Masons viewed the fraternity as an existential threat to the budding country’s republican values, they turned to grassroots democratic mobilization to uproot it.

The Anti-Masonic Party grew into a national force vying for power up and down the ballot in the 1830s. It was the first such third party in the country, dwarfed by the National Republican Party (later the Whigs) and the Democratic Party. The Anti-Masonic Party held the first presidential nomination convention of any political party in U.S. history in Baltimore in 1831, choosing former U.S. Attorney General William Wirt for their ticket. Wirt garnered more than 100,000 votes (almost eight percent of the popular vote) and won the sole state of Vermont in the 1832 election. The party also elected Vermont’s governor along with plenty of local and state seats, but it fizzled out over the course of the decade.

The question of the Anti-Masonic Party’s legacy is anything but settled among political historians. Was it all a righteous democratic force for justice or a cynical conspiracy cult? Many have cast the Anti-Masonry movement as a right-wing reactionary one, citing the economic angst and ardent religious character of its adherents. Although “its witch hunting disrupted churches, families, and communities,” Anti-Masonry had a negligible effect on American politics, according to Donald J. Ratcliffe.

But two-time Pulitzer-winner Richard Hofstadter, writing on the “paranoid style” of American politics in Harper’s in 1963, allowed that Anti-Masonry “was intimately linked with popular democracy and rural egalitarianism.” Other histories have also credited the Anti-Masons for enshrining democratic processes as a populist force for “equal rights, equal laws, and equal privileges.” Author and historian Ron Formisiano examines the populist aspects of Anti-Masonry in his book For the People … . He says that Anti-Masonry has received similar unfair treatment as other American third parties in the 19th century, reduced to “movements of bigotry” without consideration for the complexity therein. He claims the Know Nothing Party is similarly derided and misunderstood in modern times in spite of its connection with important, democratizing reforms.

The kneejerk labeling of Anti-Masons as religious zealots and reactionaries has met resistance as historians like Kutolowski have more closely examined the circumstances around the movement.

Kutolowski says the Anti-Masonry movement had “an enormous role in the development of American political culture.” In addition to pioneering democratic political party operations like the national nominating convention, Kutolowski points to the party’s championing of reforms like making kidnapping a felony and ending the appointment of jurors by sheriffs, as well as their backing of economic goals that would become mainstream, like antitrust laws. After its dissolution, much of the movement’s supporters would turn to the cause of anti-slavery.

With regard to the Anti-Masons’ primary goal — the complete abolition of the fraternity — they were, of course, unsuccessful. Though the reputation of Freemasonry was tarnished for decades, Mason lodges still operate in the U.S. and around the world. Masonic history of the Anti-Masons has often cast the phenomenon as a paranoid, discriminatory crusade. Even in recent years, members of the “ancient and honourable order” have occasionally decried public “misconceptions” about their organization, namely regarding the inconsistent inclusion of women among lodges.

The popular movement against Masons is long over, but in the age of social media — one in which virtually any conspiracy theory can take root — anti-Mason rhetoric is still out there. The charges leveled against Masons indiscriminately by internet users are much more complicated than those out of Western New York a few centuries ago. Conspiracy theorists on social media have woven anti-Masonic theories into the lore of “QAnon,” along with many other theories regarding a cabal of satanic, cannibalistic pedophiles and the Trump administration’s heroic crusade against them. Such posts might call attention to Masonic-seeming symbols in photographs of the British royal family or in the logos of Gmail or government seals. The implication is that Freemasons (along with Illuminati, Hollywood, Democrats, and Jews) exert far-reaching influence in government and culture and hint at their schemes with cryptic numerology. Recent studies have documented enormous spikes this year in social media users spreading the baseless QAnon theory, leading to several platforms taking steps to remove such content.

Kutolowski has not followed much recent news about QAnon or current conspiracy theories around Freemasonry, but she says they could be with us for a long time. She is adamant that the Anti-Masons of the 1820s and ’30s — unlike Pizzagaters and QAnons — have been branded unfairly as wacky conspiracy theorists by historians and journalists. She recalls the words of an Anti-Masonic town leader, defending the veracity of their cause: “All the evidence of historic demonstration will be necessary to convince those that come after us that the record is true.” But, as Kutolowski’s work might demonstrate, the existence of such evidence is not necessarily enough; someone must be willing to seek it out.

Featured image: “The Lord’s Prayer of the Freemasons,” Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, 1870 and Illustrations of Masonry, Utah Lighthouse Ministry, 1827

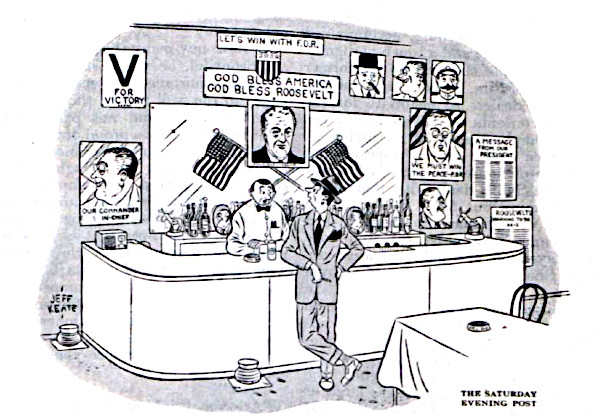

Cartoons: Election Time

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Jeff Keate

October 7, 1944

Bill King

September 13, 1952

Hoff

July 12, 1952

Richter

March 15, 1952

Stan Hunt

December 8, 1951

Clyde Lamb

December 1, 1951

David Pascal

November 5, 1955

Don Tobin

November 4, 1950

Mary Gibson

November 4, 1944

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Why Is Our Country So Divided (and What Can We Do About It)?

The name of our nation claims we are united, but one could compile a history of America just by chronicling our civil conflicts. Starting with the clash over the independence movement, Americans have been bitterly divided over tradition, faith, morals, and the rights of people of color, women, the poor, immigrants, and other groups. And, of course, we are divided between political parties.

Today, there’s a deep gulf in American opinion, which seems to be growing wider and deeper.Back in 1994, a Pew Research Poll reported that the partisan split over racial discrimination, immigration, and international relations was 15 percent. By 2017, it was 36 percent.

Spencer Critchley, author of Patriots of Two Nations: Why Trump Was Inevitable and What Happens Next, says that behind many of our arguments lie polarized views of the world that go back to our earliest days.

Critchley explains that on one side are the followers of Enlightenment, who believe in science, reason, and the rule of law. It was enlightenment thinkers who framed our government and wrote our Constitution. Today’s followers of the enlightenment believe in a “civic nation,” founded on a social contract between the individual and the state. The citizen exchanges a measure of personal liberty for membership in a mutually supportive society.

On the other side are followers of the Counter-Enlightenment, who believe a focus on reason is too constraining. It doesn’t account for culture, art, tradition, spirituality — the elements that bring richness to life. This group believes in an “ethnic nation,” which is rooted in their race and culture. While this focus can appeal to bigots, counter-enlightenment people are not necessarily racist. In an interview with the Post, he said,“Many thoughtful people come from the counter-enlightenment world view.”

The gap between the two world views is so great that Critchley, a former campaign advisor to Barack Obama, says that it has created alienation and suspicion, helped on by politicians and the media playing on resentments. “Much of the division has been exaggerated,” he says. “A lot of money can be made by making people angry and afraid.”

Yet there are a considerable number of Americans who have embraced the extremes of ideology. At the far extremes of counter-enlightenment are white supremacists. At the other extreme are people who Critchley says believe in “identity policing, endless litigating, political correctness, and punishing people for not being ‘woke’ enough.”

Critchley, who considers himself part of the enlightenment crowd, is aware of how easy it is to dismiss the opposing points of view. He says, “We live lives of high rationalism most of the time. We think in terms of facts, logic, productivity. We tend to believe facts and logic explain everything.”

The two groups’ attitudes toward culture is significant, he adds. “Enlightenment people can become disconnected from any particular culture. This is part of what’s behind the ‘globalist’ charge. Sometimes that refers to the global financial elite, and sometimes it’s veiled antisemitism, but it can also point to this sense of cultural emptiness.” Critchley says that globalism is a concept that disconnects people from the symbols and traditions that shape their lives. Critchley compares it to the campaign to teach Esperanto, “the international language.” He wonders at “the idea that anyone would want to speak a language rooted in no culture at all.”

What is true in language is also true of history, art, and human psychology. Counter-Enlightenment people “would argue that people are inherently subjective and tied to a particular location.” Culture is crucial.

Says Critchley, “The Democratic party — I’ve seen it up close — is sometimes stuck in a science-driven world. They’re really good at using science and coming up with solutions.” But they can be oblivious to culture.

“A lot of liberals would be surprised that while more than 90 percent of Blacks consider themselves Democrats, only about a quarter would define themselves as liberal.” Critchley says that they need to recognize “there are many cultures alive in the Black community.”

The current level of social friction threatens to get out of hand. But the situation can’t be blamed on a polarizing president and the general tone of today’s politics, Critchley maintains. The ideological division is far older and runs far deeper, and will still be with us after this administration has gone.

Sooner or later, we must make the effort to reunite. The solution, Critchley says, is like dieting: “it’s simple but it’s hard.”

When talking with someone with a different perspective, he advises, “stop trying to make sense for a while, stop trying to correct them. Practice some awareness, compassion. And find some shared values.”

It will probably take some digging and the results may be surprising. “We must learn to respond to people in a more intuitive way,” Critchley says. “We must build trust. Connect first, debate later.”

Featured image: Map from the cover of Patriots of Two Nations: Why Trump Was Inevitable and What Happens Next by Spencer Critchley (McDavid Media, ©Spencer Critchley. All rights reserved.)

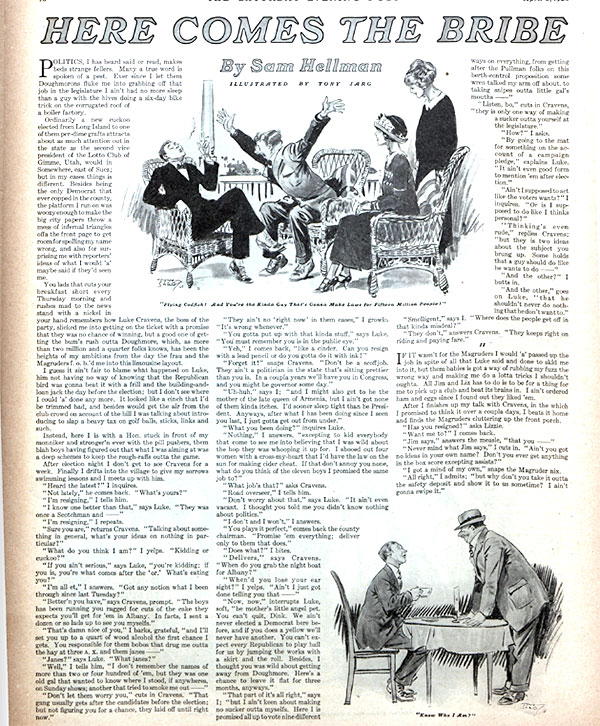

“Here Comes the Bribe” by Sam Hellman

A newspaper reporter and fiction writer with a healthy sense of self-deprecation, Sam Hellman wrote in 1925 that “those who have been reading my stuff will hardly believe that I am a college graduate with an early academic penchant for Greek accusatives and Latin gerundives.” In his humorous stories, witty commoners with crude dialect dress each other down in farcical situations. In spite of his highbrow studies, Hellman observed people and their language while traveling the country after college. In “Here Comes the Bribe,” a scrappy Long Islander accidentally finds success in politics.

Published on April 5, 1924

Politics, I has heard said or read, makes beds strange fellers. Many a true word is spoken of a pest. Ever since I let them Doughmorons fluke me into grabbing off that job in the legislature I ain’t had no more sleep than a guy with the hives doing a six-day bike trick on the corrugated roof of a boiler factory.

Ordinarily a new cuckoo elected from Long Island to one of them per-dime grafts attracts about as much attention out in the state as the second vice president of the Lotto Club of Gimme, Utah, would in Somewhere, east of Suez; but in my cases things is different. Besides being the only Democrat that ever copped in the county, the platform I run on was woozy enough to make the big city papers throw a mess of infernal triangles offa the front page to get room for spelling my name wrong, and also for surprising me with reporters’ ideas of what I would ’a’ maybe said if they’d seen me.

You lads that cuts your breakfast short every Thursday morning and rushes mad to the news stand with a nickel in your hand remembers how Luke Cravens, the boss of the party, slicked me into getting on the ticket with a promise that they was no chance of winning, but a good one of getting the bum’s rush outta Doughmore, which, as more than two million and a quarter folks knows, has been the heights of my ambitions from the day the frau and the Magruders f.o.b.’d me into this limousine layout.

I guess it ain’t fair to blame what happened on Luke, him not having no way of knowing that the Republican bird was gonna beat it with a frill and the building-and-loan jack the day before the election; but I don’t see where I could ’a’ done anymore. It looked like a cinch that I’d be trimmed bad, and besides would get the air from the club crowd on account of the bill I was talking about introducing to slap a heavy tax on golf balls, sticks, links and such.

Instead, here I is with a Hon. stuck in front of my monniker and stronger’n ever with the pill pushers, them blah boys having figured out that what I was aiming at was a deep schemes to keep the rough-raffs outta the game.

After election night I don’t get to see Cravens for a week. Finally, I drifts into the village to give my sorrows swimming lessons and I meets up with him.

“Heard the latest?” I inquires.

“Not lately,” he comes back. “What’s yours?”

“I’m resigning,” I tells him.

“I know one better than that,” says Luke. “They was once a Scotchman and — ”

“I’m resigning,” I repeats.

“Sure you are,” returns Cravens. “Talking about something in general, what’s your ideas on nothing in particular?”

“What do you think I am?” I yelps. “Kidding or cuckoo?”

“If you ain’t serious,” says Luke, “you’re kidding; if you is, you’re what comes after the ‘or.’ What’s eating you?”

“I’m all et,” I answers. “Got any notion what I been through since last Tuesday?”

“Better’n you have,” says Cravens, prompt. “The boys has been running you ragged for cuts of the cake they expects you’ll get for ’em in Albany. In facts, I sent a dozen or so lads up to see you myselfs.”

“That’s damn nice of you,” I barks, grateful, “and I’ll set you up to a quart of wood alcohol the first chance I gets. You responsible for them bobos that drug me outta the hay at three a.m. and them janes — ”

“Janes?” says Luke. “What janes?”

“Well,” I tells him, “I don’t remember the names of more than two or four hundred of ‘em, but they was one old gal that wanted to know where I stood, if anywheres, on Sunday shows; another that tried to smoke me out — ”

“Don’t let them worry you,” cuts in Cravens. “That gang usually gets after the candidates before the election; but not figuring you for a chance, they laid off until right now.”

“They ain’t no ‘right now’ in them cases,” I growls. “It’s wrong whenever.”

“You gotta put up with that kinda stuff,” says Luke. “You must remember you is in the public eye.”

“Yeh,” I comes back, “like a cinder. Can you resign with a lead pencil or do you gotta do it with ink?”

“Forget it!” snaps Cravens. “Don’t be a scoffjob. They ain’t a politician in the state that’s sitting prettier than you is. In a coupla years we’ll have you in Congress, and you might be governor someday.”

“Uh-huh,” says I; “and I might also get to be the mother of the late queen of Armenia, but I ain’t got none of them kinda itches. I’d sooner sleep tight than be President. Anyways, after what I has been doing since I seen you last, I just gotta get out from under.”

“What you been doing?” inquires Luke.

“Nothing,” I answers, “excepting to kid everybody that come to see me into believing that I was wild about the hop they was whooping it up for. I shooed out four women with a cross-my-heart that I’d have the law on the sun for making cider cheat. If that don’t annoy you none, what do you think of the eleven boys I promised the same job to?”

“What job’s that?” asks Cravens.

“Road overseer,” I tells him.

“Don’t worry about that,” says Luke. “It ain’t even vacant. I thought you told me you didn’t know nothing about politics.”

“I don’t and I won’t,” I answers.

“You plays it perfect,” comes back the County chairman. “Promise ’em everything; deliver only to them that does.”

“Does what?” I bites.

“Delivers,” says Cravens. “When do you grab the night boat for Albany?”

“When’d you lose your ear sight?” I yelps. “Ain’t I just got done telling you that — ”

“Now, now,” interrupts Luke, soft, “be mother’s little angel pet. You can’t quit, Dink. We ain’t never elected a Democrat here before, and if you does a yellow we’ll never have another. You can’t expect every Republican to play ball for us by jumping the works with a skirt and the roll. Besides, I thought you was wild about getting away from Doughmore. Here’s a chance to leave it flat for three months, anyways.”

“That part of it’s all right,” says I; “but I ain’t keen about making no sucker outta myselfs. Here I is promised all up to vote nine different ways on everything, from getting after the Pullman folks on this berth-control proposition some wren talked my arm off about, to taking snipes outta little gal’s mouths — ”

“Listen, bo,” cuts in Cravens, “they is only one way of making a sucker outta yourself at the legislature.”

“How?” I asks.

“By going to the mat for something on the account of a campaign pledge,” explains Luke. “It ain’t even good form to mention ’em after election.”

“Ain’t I supposed to act like the voters wants?” I inquires. “Or is I supposed to do like I thinks personal?”

“Thinking’s even rude,” replies Cravens; “but they is two ideas about the subject you brung up. Some holds that a guy should do like he wants to do — ”

“And the other?” I butts in.

“And the other,” goes on Luke, “that he shouldn’t never do nothing that he don’t want to.”

“Smelligent,” says I. “Where does the people get off in that kinda misdeal?”

“They don’t,” answers Cravens. “They keeps right on riding and paying fare.”

II

If it wasn’t for the Magruders I would ’a’ passed up the job in spite of all that Luke said and done to skid me into it, but them babies is got a way of rubbing my fuzz the wrong way and making me do a lotta tricks I shouldn’t oughta. All Jim and Liz has to do is to be for a thing for me to pick up a club and beat its brains in. I ain’t ordered ham and eggs since I found out they liked ’em.

After I finishes up my talk with Cravens, in the which I promised to think it over a couple days, I beats it home and finds the Magruders cluttering up the front porch.

“Has you resigned?” asks Lizzie.

“Want me to?” I comes back.

“Jim says,” answers the measle, “that you — ”

“Never mind what Jim says,” I cuts in. “Ain’t you got no ideas in your own name? Don’t you ever get anything in the box score excepting assists?”

“I got a mind of my own,” snaps the Magruder nix.

“All right,” I admits; “but why don’t you take it outta the safety deposit and show it to us sometime? I ain’t gonna swipe it.”

“I wouldn’t trust a politician,” says Lizzie, cold; “not even with nothing.”

“Is you really gonna take the job?” butts in Jim, quick, to cover up his wife’s fox paws.

“Why not?” I inquires.

“Well,” says he, “it’s a pretty dirty game, ain’t it?”

“Ever play in it?” I wants to know.

“I wouldn’t touch it with a six-foot pole,” he comes back. “They ain’t nobody in politics but a lotta grafters.”

“We once lived in a house,” says I, “where we had a furnace that was always on the bum. One day it got so cold I went downstairs to see what the hell. I found out the janitor was peddling the coal I’d bought and hadn’t taken the ashes out for a month. So I canned him, cleaned the thing out myself and never did have no trouble after that.”

“You should oughta get the kinda furnace we is got,” remarks Lizzie. “Jim says — ”

“The furnace I’m talking about,” I continues, “is a figure in speech.”

“Ours is a Little Diamond Hot Box, ain’t it, Jim?” inquires the sciatica.

“Where’d Lizzie go?” I asks, acting kinda surprised.

“I’m here,” she answers, wide-eyed.

“You’re here, all right,” says I; “but you ain’t there. What I was trying to broadcast,” I goes on, turning to Magruder, “before that frau of yourn turned on the statics, was the idea that if you don’t like dirt you can’t cuss it outta the room; you gotta grab a broom and sweep.”

“I suppose,” sneers Jim, “you’re gonna make politics as clean as a hind tooth, huh?”

“I’ll maybe try,” I answers. “What’ll you do? Stand around while some dip frisks your pockets and bawl out the coppers instead of taking a crack at the crook?”

“Jim ain’t afraid of nothing,” says Lizzie.

“I ain’t afraid of my wife neither,” I shoots back.

“You calling me nothing?” busts out the misses, who ain’t said a word so far.

“Not a thing,” I returns, hasty. “You vote at the last election, Jim?”

“What for?” he comes back. “They don’t count ’em anyways.”

“Well,” says I, “it’s a cinch they don’t count them that ain’t cast. When I gets to Albany — ”

“So you’re going?” interrupts Magruder.

“Yeh,” I tells him. “I kinda feels that I owes that much to prosperity. I’m looking ahead to the time when Dink O’Day Day will be celebrated from Rock Bound, Maine, to Climate, California, and when statutes of me in the parks will be as thick as empty shoe boxes after a church picnic.”

“You’ll look swell in the legislature,” sarcastics Jim. “What do you know about parlor-mantel law?”

“No more’n I know about kitchen-sink law,” I admits; “but it won’t take me more’n a minute and a half to run it down and make it drop from exhaustion.”

“I never seen a guy hate his wife’s husband like you does,” says Magruder. “Ever hear of Roberts’ Rules and Orders?”

“I don’t wear no man’s collars,” I answers, “and that bird Roberts ain’t gonna give me no orders. Anyways, Luke Cravens is the boss of the district. Where does this Roberts boy — ”

“You wouldn’t understand,” cuts in Magruder, “even if you knew. For example, suppose you was to get on the floor of the house — ”

“Who’s gonna put me there?” I yelps. I don’t want you to get no ideas I’m such a stupe as I sounds, but I’m even willing to carry that reputation for the pleasures of razz-jazzing Magruder.

“I mean,” he explains, “if you was making a speech on some bill and a bobo should get up and move that it should be put on the table, what would you do?”

“It all depends,” I answers, “on the way he said it. If he was nice and polite, I’d put it there; but if he tried to rough-bluff me into doing it, I’d leave it just where it was and he’d probably spend the next few minutes picking a inkwell outta his hair.”

“Flying codfish!” hollers Jim, waving his hands like a yell leader. “And you’re the kinda guy that’s gonna make laws for fifteen million people!”

“That’s what,” says I; “but what do you expects if right thinkers like you won’t take no interest in politics and’d rather play golf than vote?”

“Talking about golf,” comes back Magruder, “is you really gonna introduce that tax bill?”

“I’ll tell the popeyed world I am,” I replies. “A dollar on each ball and five fish on each club.”

“Think you can put over a grab like that?” he asks.

“I wouldn’t be so surprised,” I answers. “When I gets done telling the boys about the terrible housing conditions of the ducks on Long Island on account of the land being drug out from under ’em for golf courses, I expects the tax’ll go with one big sob. D’you know things is so bad on the North Shore that seven and eight ducks is gotta sleep on one rock?”

“I didn’t even know ducks slept on rocks,” remarks Lizzie.

“You should study national science, gal,” I returns. “What’d you suppose they slept on? Credit? Where’d you imagine the expression ‘duck on the rock’ come from?”

“I don’t know,” says she.

“I don’t know the name of the saloon neither,” cuts in Kate, slipping me the glare to sidetrack. “Please stop teasing Lizzie and try and give a imitation of talking sense.”

“Who should I imitate?” I inquires. “Jim?”

“You couldn’t go further and do worse,” suggests the Magruder exposed nerve; and when I starts laughing she goes on, all flustered, “I means, you could go further and do no worse.”

“That’ll be enough,” yelps Jim. “I’ll do my own answering back from now and on. Cutting the kidding cold,” he continues, turning to me, “I thought that golf-tax idea of yourn was to keep the cheap johns from building links around Doughmore and the other swell clubs.”

“Even a natural error like you,” says I, “couldn’t be no wronger. Can you see me pulling chestnuts at a fire for the plutocats around here? I’m a friend of the common people and — ”

“The commoner, the friendlier,” interrupts the frau.

“Maybe,” I admits; “but I promised the duck growers of this district that I’d go to the front for ’em, and a promise and a performance with Dink O’Day is as alike as two peas in a puddle. Experts has tried with instruments and them slow movie cameras to find a difference between ’em, but without no luck. It was funny. Oncet they was studying a promise of mine, and when I told ’em after a coupla hours it was really a regular performance and not no promise a-tall, they just gave up.”

“Doing business with a politician,” remarks Magruder, “I guess they hadda. When you gets to Albany them experts’ll be able to leave their naked eyes at home and still see the difference.”

“What makes you think so?” I inquires.

“Didn’t I hear you tell that Glumph woman you was gonna pass a law to stop all picture shows on Sunday, Wednesday and the nights the Ladies’ Aid met?” asks Jim.

“You did,” I tells him.

“Yeh,” jeers Magruder; “and wasn’t I there when you promised Mildew down at the Tivoli that you’d put the censors on the hummer and fix it so the film folks could do anything they wanted to, within reason and without?”

“Such is the case and the facts in it,” I confesses. “What about it?”

“How you gonna keep both promises?” demands Jim.

“What,” says I, “leaving out present company, could be simpler? I’ll introduce the bill the Glumph frill wants and also the one Mildew’s after.”

“How,” yelps Magruder, “can you be on both sides at oncet?”

“Ah,” I returns, “that’s what makes politics a art. What’s wrong with the way I’m doing? Some of the folks in the county wants this; some others don’t want that. Who’m I to say what’s proper for ’em? I’m just like a waiter in a restaurant. Everybody that comes in asks for something different. I puts in the order. If the chef don’t wanna cook up the mess, whose fault is it? A jane drifts in with her trap all set for a pair of fried wizzle-wumph eggs, sunny side up. Is it my business to tell her they ain’t good for her complexions and try and set her up to a platter of raw ox ears?”

“You mean rare, don’t you?” inquires Lizzie.

“I don’t know no more what you’re talking about than you do,” says Jim; “but how you gonna vote on these different things when its comes to a show-down?”

“O’Day,” I replies, “is far enough down on the roll call for my judgment and my conscience to get together before I has to. I’m gonna introduce everything that anyone wants and let ’em take their chances. Personally, nothing don’t interest me excepting my duck bill, and I shall fight for it with all the powers I has, with faith in the right and — ”

“Oh, hire a hall!” snaps Magruder.

“The Monday Club’s got a dandy place,” says Lizzie. “You can get it for fifty dollars a night; besides, they is still got the decorations up from the Pappa Eta Motza sorority dance.”

III

Me and Cravens goes to Albany together, Luke figuring on introducing me around to the high moguls of the party and seeing that I get started off K.O.

“You’ll be kinda busy getting settled,” says he, “so I has taken a little work off your hands.”

“What work?” I asks.

“Well,” he answers, “I figures they is about eight jobs you’ll get to hand to the boys in the district and I’ve picked ’em for you. Seeing as I got you into this, the leastest I can do is to save you from being bothered. I has even notified the lads we’s named.”

“That’s nice,” says I; “but — ”

“’S all right, Dink,” cuts in Luke. “They ain’t no thanks necessary. It’s maybe taken up some of my time and all that; but when I likes a guy, going to trouble for him’s a pleasure.”

“Yeh,” I returns; “but how about them fifty or sixty birds I promised plums to?”

“Albany,” answers Cravens, prompt, “is quite a town. They is a coupla good hotels, and I knows a restaurant I’ll take you to, where you orders tea and gets what you meant.”

Not caring nothing about them jobs at Doughmore, I don’t chase the subject no further. Anyways, I don’t aim to stay long. My ideas is to stick around the legislature just enough to see what makes the thing tick and maybe pull a stunt or two that’ll get me in bad with the jokes at home, after which me and politics’ll call it a day.

Luke makes me acquainted with a bunch of bobos that is supposed to run the works and winds up by taking me to the mansion to meet the governor. He turns out to be a decent feller.

“I has heard a lot about you,” says he to me.

“I’ve seen your name mentioned, too,” I comes back, not to be undone in courtesies.

“I wanna talk to you someday about taxes,” he goes on. “I understands you has studied ’em deep.”

“Governor,” I replies, “I don’t wanna brag, but if they is anything about taxes I don’t know it musta been sprung the day after tomorrow.”

“That’s fine,” smiles the big chief. “They is causing us a lotta trouble. ‘

“Unwrinkle your brow, gov,” I cuts in. “My golf bill will solve everything.”

“I must look into it,” says he, and me and Cravens beats it.

“I thought,” remarks Luke, “that you canned that tax idea of yourn when the Doughmorons started being for it.”

“No,” I tells him, “I’m going through with it just to prove to them coupon barbers that they give me the wrong rap.”

“Well,” says Cravens, looking at me kinda narrow, “the play might work out good for you at that.”

“You mean,” I asks, “the bill might pass?”

“It’s got as much chance of doing that,” he answers, “as one of them ducks of yourn would have in a scrap with three wildcats, four hyenas and a pair of Australian gluffaws.”

“I don’t get you,” I returns, puzzled.

“No?” smiles Luke. “All right, Rollo, roll your own hoop. If you should want me to cut in later on, you knows where to find me.”

I’m still all up in the air trying to figure out what Cravens’s been driving at when I gets to the hotel by myselfs and runs into Shem Conover, a baby from up in the state that was knocked down to me earlier in the day as a real slicker in jamming stuff through the House.

“I been waiting to see you,” says he. “I wanna little chin-chin.”

“About which?” I inquires.

“That golf-tax bill you’re touting,” he answers. “Need any help?”

“I ain’t so sure I’m going through with it,” I tells him, not liking the bimbo’s looks.

“Who’s been talking to you?” he asks, slipping me the narrow eye like Cravens done.

“What you getting at?” I yelps, getting kinda peeved at the mystery stuff.

“Listen, bo,” says Conover, “and don’t try and gruff me off the lay. If you wanna get any action with that bill of yourn you gotta be sweet to me. I’m chairman of the committee that’s gonna get it, and if you don’t put me in the line-up — ”

“What’ll you do?” I barks.

“I’ll fix it,” he comes back, slow, “so that the chloroform won’t work when you want it to, and when you gets ready to deliver the body you’ll find the livest corpse you ever seen.’

“I’ll sue the Central for this,” says I. “When a lad buys a ducat for Albany they ain’t got no right to dump him off at Matteawan.”

“You’re in Albany, little one,” remarks Conover, cold; “and when you is in Albany you gotta do like the Albanians does. Do I get a hand dealt me?”

“I ain’t gonna introduce the bill,” I growls, “and besides — ”

“Too late,” interrupts Shem. “If you run out on it I’ll have it introduced as a committee measure. The idea’s too cushy to drop. They worked it with patent medicine down in Arkansas and with baking powder out in Missouri, but the golf act’s a new one on the sandbag circuit. Give it a coupla thinks,” he finishes up, and drifts away casual.

I looks around expecting a guy in blue with a bunch of keys to grab him, but nothing like that don’t happen. Dizzy and woozy, I drifts across the street to the restaurant Luke told me about and squats me down.

“What’ll you have?” asks the waiter.

“A cup of tea, God forbid,” says I.

It’s wonderful what a little oolong will do for a lad that gets the kind he means instead of the sort he asks for, and right away I begins to perk up some. But it don’t last long. I’m about to yell for an encore when I looks up to see a feller standing besides me, a stout, surtaxy appearing citizen with a wide grin.

“Know who I am?” he inquires.

“Considering the luck I been in all day,” I answers, “you couldn’t be nothing excepting a revenue agent.”

“My card, Mr. O’Day,” says he, and slips it.

“‘August P. Stevens,’” I reads aloud, and then to myselfs, “‘representing the Universal Outdoor Co.’”

“You cover all that territory by yourselfs?” I asks.

“No,” he comes back; “I’m mostly in Albany and Washington.”

“What do you sell,” I wants to know, “scenery or air?”

“I don’t sell,” he returns, looking me straight in the eyes. “I buy.”

“What?” I asks.

“Different things,” he answers, evasive. “I suppose you know we is one of the largest sporting-goods houses in the world. Naturally, we is interested in your bill to tax golf balls and sticks. Shall I sit down?”

“If your lumbago’ll let you,” I replies; “but you might as well know later than sooner that I’ve heard enough of that bill this afternoon to last me until three weeks after my funeral. I ain’t even sure I’m gonna flip it into the hopper.”

“The boys around here,” says Stevens, “’ll tell you that I’m a square shooter and don’t mince up no words. With me a spade’s a spade and I know how to dig. What do you need to help you make up your mind about that bill?”

“Which way?” I mumbles, fanning for time.

What a zero brain I’d been not to get jerry to that talk of Luke and Conover about sandbags and chloroform and the such!

“Our way, of course,” answers the sportsgoods man. “You forget the golf tax and we’ll not forget you.”

“I see,” says I; “you wanna bribe me not to put the bill in.”

“Oh,” returns Stevens, “you can put it in; but it’ll get sick in the committee room, be operated on and die under the ether. All you gotta do is to let the dead stay dead and get all wound up in something else. You ain’t got a thing to lose. They ain’t no chance of jamming the tax over and — ”

“What do you wanna buy me off for then?” I cuts in.

“Well,” says Stevens, “they is always a outside possibility of anything going through in the last-minute rush. Besides, we don’t wanna have taxes on balls and clubs even discussed.”

“You can’t stop that,” I retorts. “I’m full of it now.”

“Full of what?” he inquires.

“Disgust,” I snaps, and ducks outta the place.

IV

They ain’t no meeting of the legislature the next day, and I runs down to Doughmore, first having wired Cravens that I was coming and for him to meet me. I ain’t one of them holier than thous, but raw work always did get me sore, even in them times when I didn’t ask a dollar bill for references. Luke sees right off that I’m riled.

“Do I look like a grafter?” I asks.

“The light ain’t so good here,” he comes, back, calm. “What makes you doubtful?

I cuts loose and tells him everything that happened to me in Albany after he left. He listens with about as much excitement as I was retailing a bright crack pulled by my third cousin’s infant progeny.

“You don’t seem surprised none,” I remarks at the finish. “Is they all dips up in Albany?”

“No,” replies Luke, “they is about 95 percent honest; but at every session in every legislature they is always a few sandbaggers — guys that push in stick-up bills, not with any hopes of passing ’em, but on it gamble that somebody will get all scared up and buy ’em off. The railroads used to be the prize marks, but — ”

“Say,” I shoots out a yelp, “you ain’t got no ideas that I’m a sandbagger, is you?”

“Well,” returns Cravens, “at first I thought that blah of yours about golf and ducks was just some pretty fun you was having with the Doughmorons; but when it flopped with them and you kept right on yelling tax, even in front of the governor, I begun to get a little suspicious.”

“Honey sweets the Malay’s pants!” I hollers.

“Huh?” inquires Luke.

“That’s Latin,” I explains, “for lads with evil minds that thinks everybody else is got ’em.”

“Evil mind, eh?” says Cravens, kinda peevish. “Any bird that’ll go to the front for a new nuisance tax, when everybody in the country is nearly bent over double carrying the load of ’em they got now is either a stupe or a grafter. And you ain’t so stupish.’

“Damn it,” I barks, “I’ll — ”

“Listen to me,” interrupts Luke. “I ain’t calling you a crook, but what do you expect people’ll think of a bobo in these times that’ll talk up another gouge, and picks out a nice juicy game like golf for the victim?”

“I was only kidding,” I mumbles, feeble;

“I suppose,” admits the chairman; “but like the feller remarked after lugging careless baby six blocks, they is such a thing as carrying a kid too far.”

“It seems to me,” says I, suddenly remembering his stuff in Albany, “you was willing to take your bit.”

“I was,” he answers, cool, “I don’t never throw no spoons away when it’s raining soup.”

“Gosh,” I groans, “I’m in a swell fix. If I don’t introduce that bill now they’ll say I been bought off. If I does, I’ll have to go to the mat for it and keep fighting all the time I’m gonna resign,” I announces, blunt.

“That’ll be the worst yet,” says Cravens “Then they’ll figure you was bought off good and was afraid of a investigation.”

“What shall I do?” I asks.

“Just forget all about it,” advises Luke. “I’ll fix things with Stevens and Conover so nothing’ll ever be mentioned about the golf bill.”

“Sure you can?” I wants to know.

“Certain sure,” says Cravens. “Won’ I the guy that sent ’em to see you?

On the way to the house I meets up with Lizzie. “I just been to the Monday Club,” she tells me. “You still wanna hire a hall?”

“No,” I answers, “not a hall — a hole.”

“A hole?” repeats Lizzie. “What you gonna do with a hole?”

“Crawl in,” says I.

Featured image: “Flying codfish! And you’re the kinda guy that’s gonna make laws for fifteen million people!” (Illustrated by Tony Sarg)

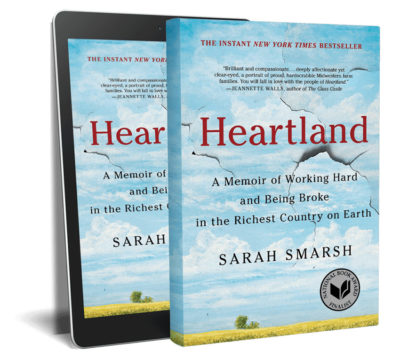

Growing Up In America’s Heartland

By the middle of the 20th century, most Americans didn’t live in rural areas. Not even most Midwesterners. But I was born a fifth-generation Kansas farmer, roots so deep in the county where I was raised that I rode tractors on the same land where my ancestors rode wagons.

During the 1860s, the Homestead Act invited any adult citizens or immigrants who had applied for citizenship — including, at least officially, single women and freed slaves — to occupy and “improve” an immense area west of the Mississippi River in exchange for up to 160 “free” acres.

That land had been inhabited for centuries by native peoples, of course. Those tribes had been harmed by European raiders long before the United States was formed. But the late 19th century marked the devastation of the Plains tribes as the federal government strategically and violently “removed” their people and annihilated the bison herds they followed for sustenance.

Meanwhile, 1.6 million people, many of whom were poor whites, were welcomed west with the promise of land ownership. That was profit-motivated propaganda; the U.S. had given massive swaths of land to private railroad companies with the idea that the development they promoted and enabled would commercially invigorate the country from one coast to the other.

The concern was never about the people being summoned to farm the land. It was about turning land into a commodity and immigrants into its workers.

A handful of my ancestors came to the United States in the 1800s, stopped for a generation in Pennsylvania Dutch Country, and took on the Kansas prairie by the 1880s. They could have stayed in New York City, as so many did after crossing the Atlantic. Instead, they ventured into the so-called frontier.

I grew up not knowing about that history, because my family had a way of not discussing themselves or the past. The stories I know, I know because I asked again and again. But as a child I nonetheless absorbed the self-understanding that sustains a rural people who have grown and hunted their own food for a very long time. What I understood is that we were hard workers, and what we worked was the earth.

Many who tried that work as homesteaders didn’t last more than a few years on the prairie. They shot themselves in the head while blizzards buried their sod houses in drifts. They pushed farther west toward more verdant places when drought starved their crops and therefore their children. They took a Pawnee’s flint arrow to the thigh and died from infection. Intimate problems, all of them, but ones that stemmed from public policy: The federal government had given them land to work as though the arid plains were just like rich eastern soil, as though it was a great deal. By and large, it wasn’t wealthy folks who took the offer.

Those who managed to profit or at least subsist on their land soon saw the population tide turn. After the Homestead Act, it was only a matter of decades until the American industrial revolution made cities into hotbeds of economic potential. Factory smokestacks beckoned from city skylines, and agriculture became an option rather than a requirement for the underclasses. For some of them, a new system of state universities and land-grant colleges held the promise of higher education and work in office chairs, rather than on their feet.

But once my family got to Kansas, they stayed. They worked the land too hard and too fast for the soil to keep up, and the prairie wind buried their houses in dirt. Many people fled the Great Plains then, amid the Great Depression and black, hellish, roiling clouds of dust in the 1930s. Still, my family stayed. Maybe they wanted to leave but didn’t or couldn’t. I don’t know. But not even the Dust Bowl drove them out.

It wasn’t all bad. Though money was scarce, you would have had your basic needs met because we knew how to grow and build things.

By the 1950s, advancements in farming equipment finally allowed for the economic dream of something beyond mere subsistence. Farmers were working huge swaths of land, putting away a large surplus of grain that would be distributed around the world by way of new transportation infrastructure — ports, highways, and railroads the country had invested in.

Then came trouble with banks.

Land prices rose in the 1970s, and banks started granting farm mortgages using a farm’s productivity as collateral, regardless of a family’s ability to repay. When land prices fell during my 1980s childhood, collateral value did, too; interest rates spiked, and farms were foreclosed on in droves.

They called it “the farm crisis.” Family operations went under in record numbers, and federal farm bills didn’t stop the corporate and global forces that were devastating small farmers like us. During the first 10 years of my life, from 1980 to 1990, rural Kansas lost about 40,000 residents, while Kansas metro areas gained about 150,000.

That was the climate I came up in. All around us things were closing: the small-town department store, the hardware store with its tiny drawers stretching to the ceiling, the local restaurant. Lawyers took down their small-town shingles and doctors moved to cities.

But we held on.

It wasn’t all bad, that poor rural place. Though money was scarce, you would have had your basic needs met because we knew how to grow and build things. The popular image of Kansas is a monotonous, level expanse. If you drive through without getting off the interstate highway, that might be all you see for hundreds of miles, but some corners of Kansas are made of modest hills, woods, red-rock formations, slight cliffs. Still, my family fit the stereotype as both a people and a place: farmers on flat earth.

Some of us saw a beauty in that earth that people heading west toward the Rocky Mountains seemed to miss. But the earth was more of a tactile experience than a view. We had it on us. Cars got stuck in muddy ditches after thunderstorms. My feet got stuck in the marshy edges of ponds full of cattails. Gravel got stuck in my knees when my bike tires slid on roads made of sand.

We pulled radishes out of the garden, rubbed them on our jeans, and ate them right there if we pleased because a little dirt was good for you. After a shower, it was still under our fingernails and in the grooves between our toes.

We rarely bothered to wash our cars and pickups because they went up and down muddy roads every day and what was the point? What came out of the dirt went into the kitchen. Grandma Betty showed me how to chop vegetables, peel potatoes, pull guts out of chickens, and beat the eggs they laid.

Grandma breaded pork chops Grandpa had butchered and put them in a hot skillet while I stood on a kitchen chair in my underwear running a hand mixer through a bowl of boiled potatoes and milk.

We were country people in the middle of the country, living in a way that, I gather from things they’ve said to me over the years, some middle-class people in cities and suburbs on coasts thought had died long ago. For someone who never worked a farm, for whom the bread and meat in deli sandwiches seemed to magically materialize without agricultural labor, the center of the country was a place flown over but not touched.

“I haven’t heard of anything like that since The Grapes of Wrath,” people with different backgrounds would say to me in all seriousness when I described life on the farm. They thought we didn’t exist anymore, when in fact we just existed in places they never went. It was an easy way to think, I guess. I rarely saw the place I called home described or tended to in political discourse, the news media, or popular culture as anything but a stereotype or something that happened a hundred years ago.

We were so invisible as to be misrepresented even in caricature, lumped in with other sorts of poor whites, derogatory terms applied to us even if they didn’t make sense. We lived on the open prairie, so we weren’t the hillbillies of the Smoky Mountains or the Ozarks. We weren’t roughnecks in oil fields; Kansas had a humble tap on oil thousands of feet below the prairie, but nothing like Oklahoma or Texas to the south. Redneck and cracker didn’t quite translate, since their American usage was rooted in the slave South, against which Kansas had lit many of the fires that sparked the Civil War.

Slang terms for my plains ancestors who built dwellings there from sod, the only available material for lack of trees, didn’t survive in common vernacular. We were so willfully forgotten in American culture that the most common slur toward us was one applied to poor whites anywhere: white trash. Or, since we moved in and out of mobile homes, trailer trash.

But as members of all sorts of stereotyped groups know, the popular image — selected or fixated upon by someone more powerful than you — doesn’t tell you much about the life.

For one thing, anyone who has lived it knows that what matters less than the trailer is where the trailer is parked. Ours was in the country by my father’s choice, on the land where he later built our house. The place was thought boring for being grassland — mountains and forests being the landscapes that more often inspire awe — but without hills and trees we had a bigger sky than Montana, an unobstructed view of bright color between dark thunder clouds like nothing I’ve ever seen elsewhere. Those displays were so grand outside a single-wide metal dwelling on wheels that it felt less like us having a good view than like God having a view of us. I could feel how small we were.

I knew, so deeply that I wasn’t even conscious of it, that my family was on the outside of something considered normal. That normalized thing was the city, suburbs, even little burgs of 3,000 people. We called them all “town,” even the small ones seeming to lord over us when we wore dirty jeans to visit a bank teller wearing a suit from Dillard’s. Places with banks, schools, stores, and county courthouses — let alone skyscrapers — represented to us a sort of power we were removed from, a disenfranchisement not only by culture but by geographic distance. This bred in us a distrust of just about anyone who held a power we didn’t — even those who tried to help.

I rarely saw the place I called home described … as anything but a stereotype or something that happened a hundred years ago.

“I never seen a dime of it,” Grandpa Arnie would say about Farm Aid, the concert fundraiser begun in 1985 to save dying family farms. The founders were white singers from humble places: Willie Nelson, who was born the son of an auto mechanic during the Great Depression and spent the summers of his youth picking cotton in the Texas heat. John Cougar Mellencamp, who was born in small-town Indiana and became a grandfather at age 37. Neil Young — well, he was a middle-class hippie from Canada. Grandpa Arnie didn’t know or care about any of that. All he knew was that he’d never been to a big concert in his life, and he wouldn’t get to go to this one.

All around us, farm loans were underwater. Old farmers died and their kids sold everything off; many of them had already moved to cities, which their parents often encouraged for their survival. That economic collapse deepened a consensus within society that a talented person from the country would endeavor to “get out.” Some did. They got scholarships to college, blew town, and — their politics and economic prospects having changed — never looked back. That “rural flight” made way for the idea that country people can’t “make it” in a bustling metropolis. But the ability to measure distances for planting alfalfa and smell the right moment to cut it isn’t so different from the ability to map out a subway trip and feel when a stop has been missed.

Like all industrialized countries, America started out country and turned city. My people didn’t turn with it. Instead of striving toward glowing economic meccas, they stayed on tractors in fields, or in small towns where life struck many of them as not just good enough but preferable to bigger places. Often, it’s not that country people can’t hack the city but that they choose not to — or life just played out differently regardless of their desires.

When I was a kid, the U.S. was a few decades away from reckoning with the reality that the next generation would be worse off, not better off, than the one before it. But my community had been facing dwindling odds for generations. They knew that children like me likely wouldn’t and shouldn’t aim for life on a farm. Few country kids were pressured to keep a farm going.

Well ahead of middle-class America, for all my family’s emphasis on hard work, on some level we’d done away with the idea that it always paid off. Being as we got up before dawn to do chores and didn’t quit until after dark, it was plain that the problem with our outcomes wasn’t lack of hard work. The problem was with commodities markets, with big business, with Wall Street — things so far away and impenetrable to us that all we could do was shake our heads, hate the government, and get the combine into the shed before it started to hail.

Of all the forces that caused what social scientists call rural flight, the most powerful one during my childhood was perhaps industrialized agriculture, in which big farming operations with massive machinery churn out products. Small farms like my family’s, where the pigpen contained three sows and a litter of piglets, had no place in such an economy — one that was about more, bigger, faster.

In 1980, the year I was born, there were 65,000 hog farmers in Iowa, working out to about 200 hogs per farm; 32 years later, there were 10,000 hog operations with 1,400 animals each. Meanwhile, the grain industry consolidated, shutting down local co-ops. Rural jobs dwindled, people moved away, and the services and stores and schools that couldn’t be sustained by a hundred people boarded up.

There’s another sort of rural-urban imbalance, though: When so many people migrate to and populate cities that they experience over-crowdedness and high unemployment, sociologists call it overurbanization. For working people, the fantasy of the city can shake out just as poorly as 160 free acres of hard silt. That only became more true as I was growing up. Incomes kept falling, and costs kept rising. Cities were gentrified and became unaffordable.

It wasn’t just the death of the family farm you would have been born into but the death of the working and even lower middle classes, regardless of their place.

Somewhere along the way of America, people moved from farms to cities until the nation was a more urban place than a rural one. My father’s family had held out and held on for generations, though, preferring air to asphalt and lightning bugs to streetlamps. Or maybe they were just so far off the grid that they didn’t know any other life for comparison.

If I live to be an old woman and the trends of my early life continue, by the time I die, half the Kansas population will live in only 5 of 105 counties — people consolidated like seed companies. There’s a strength in that, environmentalists and economists might suggest, but perhaps a greater weakness.

President Dwight Eisenhower, a native of rural Kansas, said, “Whatever America hopes to bring to pass in the world must first come to pass in the heart of America.” The countryside is no more our nation’s heart than are its cities, and rural people aren’t more noble and dignified for their dirty work in fields. But to devalue, in our social investments, the people who tend crops and livestock, or to refer to their place as “flyover country,” is to forget not just a country’s foundation but its connection to the earth, to cycles of life scarcely witnessed and ill understood in concrete landscapes. For a sustainable world, one in balance both economically and environmentally, the American heart needs a strong, well-supported, well-respected chamber outside its metropoles.

The life force that flows back into it will likely be from other places. The meatpacking towns of western Kansas, for instance, have become some of the most ethnically diverse places in the country as immigrants stream in from Mexico, the Middle East, and Central America to take factory jobs amid industrial agriculture’s boom.

Statewide, according to the 2010 census, many rural counties had declined, and more than 8 out of 10 Kansans were white. But the Hispanic population had grown by 60 percent in the last ten years. That’s a demographic shift not without tensions but one that has been embraced by some small-town whites, who knew their home must change to survive. As Europeans who moved west and built sod houses on the prairie learned, you either work together or starve alone.

Of all the gifts and challenges of rural life, one of its most wonderful paradoxes is that closeness born of our biggest spaces: a deep intimacy forced not by the proximity of rows of apartments but by having only one neighbor within three miles to help when you’re sick, when your tractor’s down and you need a ride, when the snow starts drifting so you check on the old woman with the mean dog, regardless of whether you like her.

When I was well into adulthood, the U.S. developed the notion that a dividing line of class and geography separated two essentially different kinds of people. I knew that wasn’t right, because both sides existed in me — where I was from and what I hoped to do in life, the place that best sustained me and the places I needed to go for the things I meant to do. Straddling that supposed line as I did, I knew it was about a difference of experience, not of humanity.

From Heartland: A Memoir of Working Hard and Being Broke in the Richest Country on Earth by Sarah Smarsh. Copyright © 2018 by Sarah Smarsh. Reprinted by permission of Scribner, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

This article is featured in the January/February 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Are Evangelicals Actually All-in for Trump?

Earlier this month, President Trump spoke before a group of evangelical Christian supporters at the Ministerio Internacional El Rey Jesús in Miami. That morning, the president had ordered a drone strike that killed Iranian military leader, Maj. Gen. Qassim Suleimani, and his address to the largely Hispanic crowd touched on national security, religious freedom, and his potential opponents in the Democratic Party.

According to exit polls by Public Religious Research Institute, Trump has enjoyed support from white evangelical voters in higher numbers than the previous three Republican presidential candidates. Many high-profile evangelical leaders’ disavowals of the president have raised questions about whether Trump can maintain support from this loyal coalition.

Another question, however, is appropriate: Who, exactly, comprises this group of “evangelical Christians” and how can we understand this movement that has become seemingly inextricable from the Republican Party in recent decades?

Thomas S. Kidd, a self-proclaimed evangelical and the Vardaman Distinguished Professor of History at Baylor University, has written Who Is an Evangelical: The History of a Movement in Crisis to attempt to answer these questions. Though Kidd, a former Republican, says he couldn’t ever bring himself to support President Trump, he understands the tendency for white evangelicals to do so. But, he says, the larger evangelical community — including those at Trump’s rally in Miami — holds more diversity than people think, and the allegiances of born-again Christians aren’t necessarily in Trump’s pocket.

The Saturday Evening Post: What is an evangelical?

Thomas S. Kidd: The simplest definition is just evangelicals are born-again Christians, but, of course, there’s a little more to say than that. I define it by three characteristics. One is to be “born again” or converted. Another one is a very high view of the Bible as a source of religious truth, and, finally, an ongoing sense of the presence of God in your life — a personal relationship with Jesus, or walking in the Holy Spirit. People would describe this different ways. Those things are not utterly unique about evangelicals, but I think they’re distinctive enough to set them apart from a lot of other kinds of Christians. I think those are historical and spiritual attributes to evangelicals, but also it gets beyond a sort of America-focused and political definition of who evangelicals are.

SEP: Another attribute of evangelicals that I’ve come across is proselytism. I’ve seen others include that in a definition of evangelicals.

Kidd: Yeah, Some people have put that under a category of general activism, or a kind of missionary impulse. I think that’s definitely an evangelical attribute, or at least it’s supposed to be, but, if you look at it historically, Catholics beat Protestants to the punch on missions by about a hundred years. I might make that a little less of an evangelical trait, but it definitely counts as one.

SEP: Would you say that the evangelical movement is growing?

Kidd: I think in the United States, it’s probably holding steady. The growth areas are mainly among charismatics and Pentecostals, and especially among immigrant groups — most obviously among Hispanics, but also among Asian and African immigrants. A lot of that tends to be off the radar screen, because those people are either not involved in politics or their political allegiances are more up for grabs than white evangelicals. I think white evangelicals are on a slow decline — not catastrophic, but a slow one. For instance, there’s been a slow decline in the Southern Baptist Convention over the past decade or so. The people that we tend to recognize most readily as evangelicals are white voters. Those people are definitely becoming a smaller percentage of the overall evangelical population in America.

SEP: In your book, you write about the white, conservative movement that most associate with evangelicals, particularly the media. If that isn’t the whole story, then what would you call that group otherwise?

Kidd: I think the term evangelical is going to be used in the media, so I think it’s probably futile for us to come up with other names. For me, personally, the only commitment I have to the term evangelical is that it’s a biblical term, meaning “good news.” In that sense, Christians can’t get away from the term evangelical. Some people have proposed terms like “gospel Christians” or “Jesus-followers” to bring some detachment from politics to the term. My view is that we’re kind of stuck with the term evangelical, so part of what I’m trying to do is to give a more historical and global view of what the term means and disconnect it a little bit from contemporary American politics.

SEP: If evangelicals aren’t united under support of the Republican party or the current administration, how would you say they are united?

Kidd: Well, they’re united in the characteristics that I’ve listed: conversion and the Bible and the felt presence of God. That allows you to look at evangelicalism as a global movement, so evangelicals in Brazil, Nigeria, and China are united on those kinds of attributes, but not on American political issues.

I do think in America there would be a pretty broad commonality on cultural and social issues. For instance, even though African American evangelicals tend to vote Democrat, they would be the most likely Democrats to have conservative views on marriage and abortion. Also, I think you would find a lot of white evangelicals who are more sympathetic to immigrants than other Republicans. I do think there are potential points of unity, but across those ethnic divides — especially between white and black evangelicals — in terms of electoral preferences, there’s not much unity.

SEP: Could an evangelical be a leftist?

Kidd: Sure. You don’t see very often, I don’t think, evangelicals who would be pro-choice — especially staunchly pro-choice. But, African American evangelicals are overwhelmingly Democratic. Historically, you certainly have a number of white evangelicals who, on economic issues, are leftwing. The magazine Sojourners, for instance, is a notable evangelical publication that is leftwing on economic issues — taking care of the poor, working class, etc.

SEP: You mention in your book that you’re a “Never Trump” evangelical. When did you decide that?

Kidd: I was certainly not supportive of Trump in the primaries. I was actually affiliated with Marco Rubio’s campaign, on one of his faith advisory boards. Where I saw the difference between me and most Republicans — I don’t necessarily consider myself a Republican anymore — was that the vast majority of active Republican voters coalesced around Trump. When he got the nomination, I decided I couldn’t support him.

SEP: When he is talking to his evangelical base, President Trump talks about “believers” and religion being under attack. Would you say that’s true?

Kidd: Not overall in America. I think what he’s referring to is some of the policies, especially under the Obama administration, like the HHS mandate, requiring companies to cover contraceptives, and even going after groups like the Little Sisters of the Poor, which was a major controversy, culturally. So, I think policies like that fed into a sense that the Democrats, and the Obama administration in particular, were inclined on some issues, like abortion or same-sex marriage, to require Christians to act against their conscience. I think that concern counts for Trump’s references to Christians being “under attack.”

I’m sure he would bring up the “Merry Christmas” issue too [laughs], but I don’t think that’s a very important issue. It is the sort of thing that people can understand.

But I think the religious liberty concerns are what he’s pointing to, and I think on issues like the HHS mandate, there really were religious reasons for Christians to be concerned. Whether that all amounts to Christians being under attack in America is probably overstated. But there are legal reasons for concern about religious liberty in America for sure.

SEP: You’ve talked about how you couldn’t support Trump, so where do you break from him?

Kidd: Different voters have different views on what is important, and some evangelical leaders have said that personal characteristics don’t matter that much, but I do think that they matter. For me, about half of what we’re looking for in any given president or presidential candidate is personal temperament and character. There are legions of problems with President Trump: the way that he talks about immigrants, the profanity, the Access Hollywood tape. There are all kinds of things you could list that are problematic, as far as character issues, with him. Policy-wise, I’m all for border security, but there are serious problems with the ways he has talked about both Latino and Muslim immigrants.

There are areas where I think evangelical support for Trump has panned out well. I think he’s made good nominations to the Supreme Court and other parts of the federal judiciary. I don’t think that white evangelical support for Trump has turned out to be absolutely unwarranted or foolish. But, for me, the character and confidence issues continue to make him unqualified for office.

SEP: How do you contend with that evangelical support for Trump? Would you urge other evangelicals to drop their support for him?

Kidd: Well, I think it depends some on what happens in terms of the democratic nominee. I didn’t vote for Hillary Clinton either. I didn’t feel like there was a good alternative for evangelicals in the 2016 election. Because of that, I didn’t feel that there was one acceptable option. What I’ve often said is that I don’t understand the enthusiastic support of Trump where he can do nothing wrong. That, I think, is especially unseemly. But I can understand why evangelicals would have voted for Trump, and I can understand why some evangelicals even voted for Hillary Clinton. I personally don’t think evangelicals had good options in 2016, and I suspect it’s going to be the same in 2020.

SEP: What about Pence? Is he a good representation of what evangelicals are looking for in a politician?

Kidd: My main concern about Pence is the way he has enabled Trump to do what Trump does, but I do think had Pence been a candidate in 2016 that he would have been a better alternative for evangelicals. Evangelical support in the 2016 election was deeply divided between Trump, Rubio, and Cruz. It wasn’t until the general election that white evangelical support largely coalesced around Trump. It’s a tough call between being willing to serve in Trump’s administration, but I think in general he would’ve been a better choice.

SEP: We have seen some evangelical leaders disavow President Trump, like Christianity Today’s former editor Mark Galli and author Beth Moore. White evangelical support for the president was polled at 81 percent in 2016 and, more recently, about 72 percent to 75 percent. Do you see that support from his evangelical base going anywhere?

Kidd: The Christianity Today editorial was certainly notable, because CT is still sort of the flagship evangelical magazine. They weren’t ever in support of Trump, though. What they did wasn’t a break with Trump; it was just coming out in favor of his removal. But, the fact they were willing to take that position was quite controversial and spectacular, and it was worth the attention that it got.