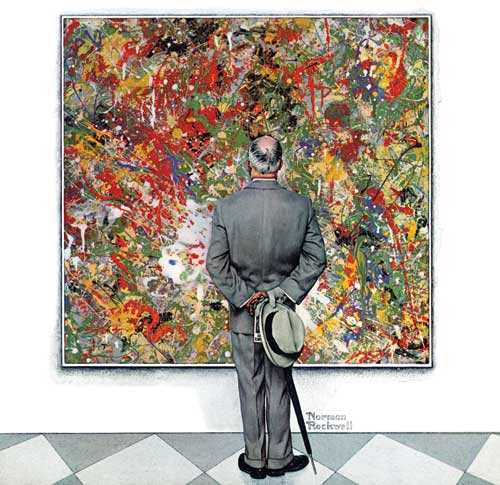

Norman Rockwell Crashes the New York Art Scene

One afternoon in July 1968 Rockwell picked up the phone in his studio and heard a voice at the other end talking intently about mounting a show of his work.

“I’m sorry,” he said, “but I think you have the wrong artist.”

He was speaking to Bernie Danenberg, a young art dealer who was in the process of renovating a space in New York that would open that September. His speciality was established American masters of the 19th and 20th centuries and his personal style was intense. A trim, voluble man in his 30s with oversize glasses, he owned a Bentley convertible (“Ming blue,” as he described it) and was seldom without a cigarette.

The next morning Danenberg drove up to Stockbridge with Larry Casper, the low-key manager of his gallery. Rockwell had instructed them to drive straight to the Red Lion Inn, across from his house, where he stored about a dozen paintings. The arrangement allowed him to minimize interruptions from people who insisted on seeing his work. It was peak vacation season in the Berkshires and tourists in wicker chairs were on the inn’s long porch when the dealers arrived. “The paintings were in there, in that room right by the entranceway,” Casper recalled. “Important pictures were hanging all over the place.”

Using the pay phone in the lobby of the inn, the dealers called Rockwell and said they were across the street. Could they come over and see him? Within a few minutes, they were striding into his red-barn studio. They explored the place as if it represented a never-excavated archaeological site, seeing treasures everywhere.

A small, lovely painting was lying on a table, Lift Up Thine Eyes. Set outside a Gothic church in Manhattan, it portrays a crowd of urbanites rushing by with lowered heads, oblivious to the uplifting message that a young man on a ladder is posting on a sign outside the church. Danenberg offered $2,500 for it. Rockwell told him to just take the painting and he may have actually meant it. “I got paid for it once. I don’t need to be paid again.” He meant he had been paid by The Saturday Evening Post.

Danenberg was persistent, and by the end of the visit, Rockwell had agreed to not only accept a check for Lift Up Thine Eyes but to allow the dealer to schedule an exhibition of his work at the gallery that October.

Rockwell still owned most of his paintings, especially the major ones, and Danenberg needed to figure out which pictures to borrow for the exhibition. Rockwell referred him to the Berkshire Museum in Pittsfield, where he kept a few dozen works. Then he made a phone call to Stuart Henry, the museum’s director. “I have a misguided art dealer here who thinks I am an artist,” Rockwell said in his deep voice. “Humor him. Open the museum.”

To read the rest of the article, excerpted from American Mirror: The Life and Art of Norman Rockwell by Deborah Solomon, pick up the Jan/Feb 2014 issue of The Saturday Evening Post on newsstands, or:

Purchase the digital edition for your iPad, Nook, or Android tablet:

Subscribe to the print edition of The Saturday Evening Post:

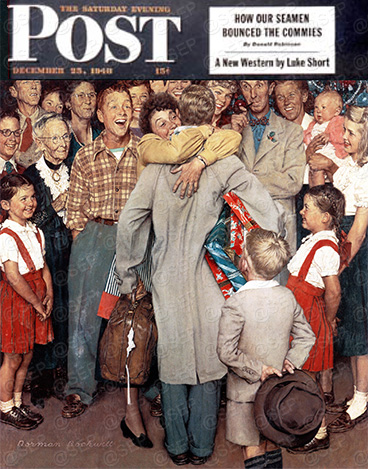

The Homecoming

The Homecoming Norman Rockwell December 25, 1948

Parents will tell you nothing makes holidays more enjoyable than visits from their grown-up children. In 1948, Rockwell created his vision of a happy Christmas reunion by gathering all three of his boys in a single painting. We see the back of his oldest son, Jerry, receiving a joyful hug from his mother, Mary. To the left of Mary, in a plaid shirt, is son Tommy. Youngest son, Peter, appears on the far left wearing glasses. To Mary’s right, with that ubiquitous pipe, is happy Dad, who occasionally made cameo appearances in his paintings.

To make this scene of the homecoming even more joyous, Rockwell added friends and neighbors from his community in Arlington, Vermont. Many of these people appeared on other Rockwell covers, like the little boy holding the hat, who was the main character in Rockwell’s A Day in the Life of a Boy. Rockwell also used the boy’s baby sitter—the blonde girl on the far right—and his mother and baby brother, who was dressed in a pink sweater. The little girls in red jumpers are actually one girl—the daughter of Rockwell’s doctor—who was so cute, he painted her as twins.

Rockwell’s good friend and fellow Post artist, Mead Schaeffer, is at the very top left. His daughters, who posed for Rockwell are also shown: blonde Lee is just left of Norman, redheaded Patty, stands to the right of Tommy. And what family gathering is complete without a grandmother? Happy to pose for the role was none other than Grandma Moses, who started painting at 67. “When I knew her,” Rockwell wrote, “she was over 85 years old, a spry, white-haired little woman. Like a lively sparrow.”

Rockwell chose his subjects carefully. He wanted to create a scene both familiar and poignant, one that would resonate with families who had known recent (and lengthy) wartime separations. Even today, Rockwell’s homecoming evokes the spirit of welcome we’d like to see waiting for us when we come home for the holidays.

Readers’ Favorite Rockwells

We want to hear about your favorite covers from The Saturday Evening Post, whether illustrated by Norman Rockwell or another Post artist. This week we’re reviewing Rockwell favorites from readers and our own staff.

The Gift

Norman Rockwell

January 25, 1936

Helen Palmquist of Lincolnshire, Illinois, went right for a fun one: “My favorite is the little boy looking in Grandpa’s overcoat, not realizing a puppy is in the other pocket.” Rockwell had his beloved Uncle Gil in mind when he created this 1936 cover. Uncle Gil was something of a scientist and inventor, Rockwell wrote in My Life as an Illustrator. “But he did have one eccentricity, he got his holidays mixed up. On Christmas day, with snow on the ground and a cold wind in the trees, Uncle Gil would arrive loaded with firecrackers to celebrate the Fourth of July. On Easter he would bring us Christmas gifts.

“He always had a kind of Christmas spirit about him—jovial, warmhearted, shouting, ‘Warm, Norman, warm!’ as I approached a hidden present and ‘Hurrah!’ when I found it. … I don’t think I have ever enjoyed any gifts as much as I used to Uncle Gil’s.”

Saying Grace

Norman Rockwell

November 24, 1951

Saying Grace is the favorite of Nicole Beer from our staff in Indianapolis, Indiana. “It reminds me of my grandmother even down to the way Rockwell painted the lady’s hands. I remember being a kid and always praying in public with her before we ate. Everyone would always stare at us and it would make me embarrassed. I hated it as a kid but as an adult, I am so thankful for her and the example she set. I can only hope I am as bold with my faith as she was.”

Saying Grace has an interesting history. Click here to read about which of Rockwell’s sons appears in this illustration and how fellow Post artist George Hughes’ discouragement drove Rockwell to complete this painting.

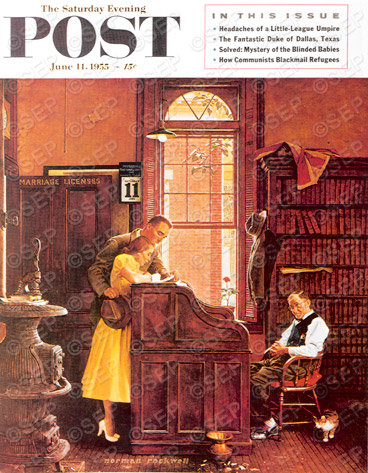

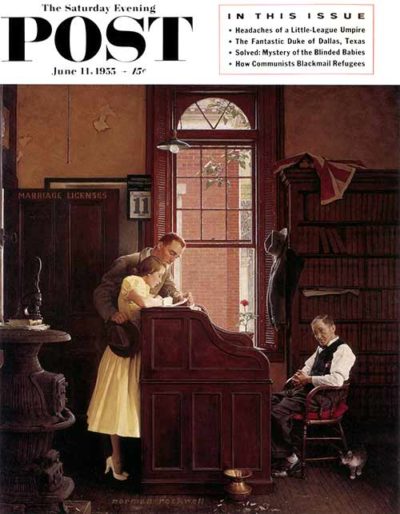

The Marriage License

Norman Rockwell

June 11, 1955

“There is only one that stands head and shoulders above the rest in terms of sheer beauty and deep meaning—The Marriage License,” writes Barbie Thompson of Calgary, Alberta.

“Manning this department, no doubt years before these two lovebirds were even born,” writes Barbie of the elderly clerk, “[he] has seen it all and therefore knows this path all too well—the Good and the Bad, the Happy and Not-So-Happy Endings. The only personal warmth for him now comes from his kitty, those well-smoked cigarettes, and the well-chewed loose tobacco targeted to the spittoon, and the slow-burning, unseen embers from that ancient cast-iron stove.”

Barbie may be more right in that last sentence than she knows. Anne Braman, daughter-in-law of the gentleman who posed as the clerk, wrote in a 1976 Post article that her mother-in law had died the year The Marriage License was painted.

Close-up of elderly clerk.

“Mr. Rockwell—knowing my father-in-law Jason C. Braman—realized how upset he was, and he thought if he could get him to model it would give him something new to think about.”

Rockwell was right about the new activity having a therapeutic effect on the widower, wrote Anne, “As soon as the The Marriage License appeared on the cover of the Post, people recognized him immediately. When his friends commented to him about the cover, he would say, ‘Would you like for me to autograph your copy?’ And he would. When I told Mr. Rockwell about this, he was quite amused.”

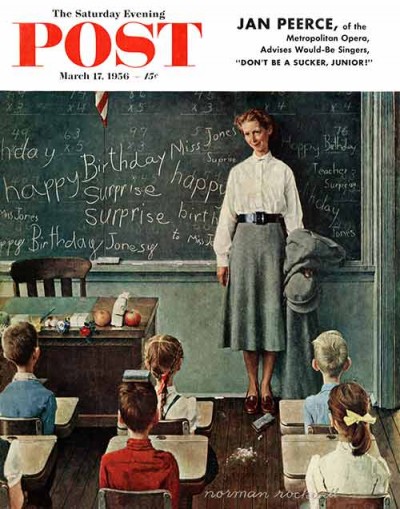

[Anne Braman modeled for Rockwell as the schoolteacher in the 1956 cover Happy Birthday Mrs. Jones. Read more about her here.]

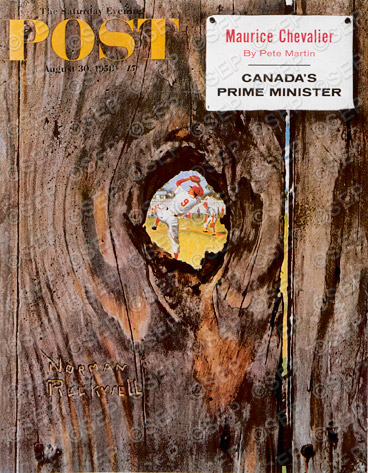

Knothole Baseball

Norman Rockwell

August 30, 2958

“I love all baseball covers, but I find this one particularly interesting,” writes Cris Piquinela one of our Post staffers.

“First off, I don’t think most people looking at this cover would think it is a Rockwell. There are no children or people visible, no characteristic facial expressions. However, what I like about this cover is that it forces me to ‘create’ or imagine the scene in my head. I can’t see the person looking through the hole, but I imagine a freckled, redheaded, barefoot kid. At the same time, I can sense the excitement of the pitch, a great hit by the player at bat, and the entire crowd going crazy. This cover does not tell me what I am looking at … it forces me to imagine it. Plus, I love only having a small piece of the image shown to me.”

Rockwell’s carved signature.

It is also interesting to note the way Rockwell “carved” his signature in the painting.

A special thank you to readers (and Post staff) for telling us about your favorite Rockwell covers!

Visit our online gallery to review Post covers by your favorite artist.

Coming soon in our Readers’ Favorites series: readers’ favorite covers from Rockwell’s neighbor, friend, and fellow Post artist George Hughes. If you have a favorite George Hughes cover (and there are 115 to choose from) we’ll be glad to feature it.

View covers by George Hughes here, then email us your name, along with the title and date or just a good description of your favorite piece at [email protected].

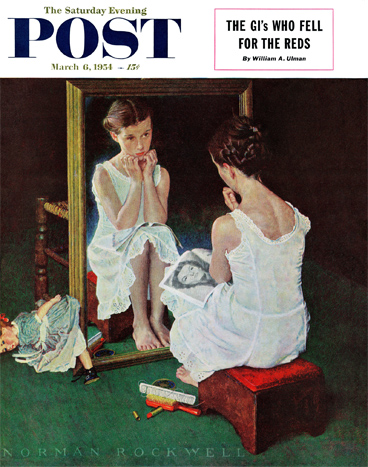

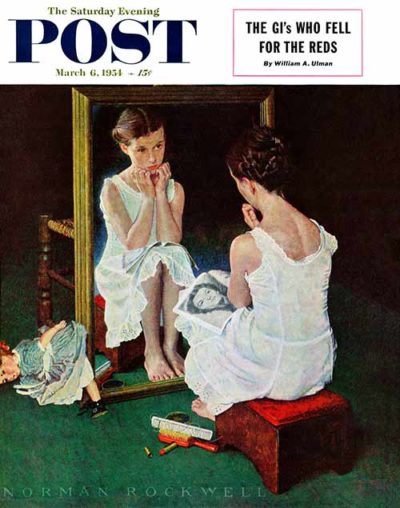

Rockwell’s Favorite Model, Part III

March 6, 1954

“He is a genius with a childlike heart, a man who leaves a lasting imprint on people as well as on canvas,” Mary Whalen Leonard told the Post in 1976. We spoke with her again recently to ask about one of Norman Rockwell’s most respected paintings—and about the artist himself.

Mary’s pose seems “apprehensive, as if she understands that womanhood is upon her and fears that she is not quite ready,” writes art expert Karal Ann Marling in her 1997 book, Norman Rockwell. However, young Mary didn’t have a clue.

“I was only in fifth or in sixth grade, and I wasn’t a kid who was at all interested in growing up. I was just having a good time,” Mary says.

He tried to explain the concept behind the forgotten doll: “You’ve tossed away your doll—you no longer play with dolls.” But Mary, who describes her younger self as a tomboy, says, chuckling, “I was saying to myself, ‘Yeah, I never did that anyway.’”

Rockwell knew that Mary wasn’t grasping the idea, so he tried again, “Now, Mary, don’t you ever stand in front of a mirror and wonder what a beautiful woman you’re going to be? I can remember standing in front of a mirror, combing my hair, wondering how handsome I was going to be.”

“And quite honestly,” she laughs, “that didn’t make any sense to me because Norman wasn’t handsome! So I didn’t relate to that. I mean I couldn’t get into it. So I think he just told me to think about being a beautiful woman and what I might do with my life. But it did not connect with me.”

Mary tells us Rockwell felt he had made a mistake including the magazine featuring sexy movie star Jane Russell. “He regretted it deeply. Norman got a lot of criticism—remember this was in the ’50s—that said, ‘Is that all a little girl can dream about is becoming a movie star?’”

“I should not have added the photograph of the movie star,” Rockwell later said in Marling’s book, “the little girl is not wondering if she looks like the star but just trying to estimate her own charms.”

In what would become one of his most respected paintings, Rockwell captured the poignancy and uncertainty of growing up despite the fact that Mary “had no idea what he was talking about.” For decades critics had dismissed Rockwell as simply a popular commercial illustrator. Today, many have concluded that some of his works, however, transcend freckle-faced boys at the ole swimmin’ hole and secure his standing today as a true artist. Girl at the Mirror is such a painting.

Mary, who describes this painting as “very different than most of Rockwell’s covers,” compares the subtle use of color and lighting with another of Rockwell’s finest works. “In The Marriage License,” she explains, “you think you’re going to concentrate on the couple getting their license, but really what you find yourself looking at and being drawn into is the sweet, dear man [the elderly clerk]. Because that’s where the light is, on his face.”

March 6, 1954

By the time Girl at the Mirror was published, Rockwell had moved from Vermont to Stockbridge, Massachusetts. “He wrote me a little note and told me it was going to come out. He sent me a photograph I posed for.”

Mary never knew why Rockwell called her his favorite model, but he had quickly become one of her favorite people. “I kept in touch with him until he died. He always sent me a little note at Christmas time and told me he missed me.”

See Mary today as she talks about the artist in this video, courtesy of the Norman Rockwell Museum.

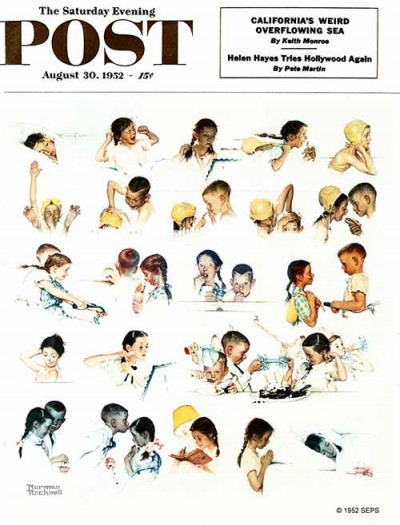

Rockwell’s Favorite Model, Part II

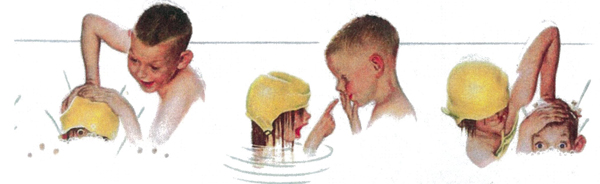

Day in the Life of a Girl

Norman Rockwell

August 30, 1952

Rockwell said he enjoyed working with 9-year-old Mary Whalen, who “could look sad one minute, jolly the next, and raise her eyebrows until they almost jumped over her head.”

“He was very inclusive; he wasn’t authoritarian, telling me what to do,” Mary says. “It was, ‘OK, this is what we’re going to do today.’ He would act it out for me.

“I was reserved and he would just sort of pull [the expressions] out of me by laughing or clapping or stomping his feet or jumping up and down and making me laugh, that kind of thing. And I just felt such a part of what was happening. As a kid, I liked to be a part of something. He knew what he wanted and he knew how to get that out of you. And then when he got [the right expression], he would just shout, ‘Oh, that’s wonderful! That’s wonderful!’”

For the 1952 cover, A Day in the Life of a Girl, Mary gave Rockwell over 20 wonderful expressions.

“It took a week,” Mary tells us, to shoot all the scenes for the 1952 cover. Beginning with getting out of bed, A Day in the Life of a Girl is done sequentially, like a movie reel. Photographer Gene Pelham took dozens of shots, as the artist posed his models.

“When I posed for A Day in the Life of a Girl,” Mary tells us, “I got up early, my mother combed my hair, did my braids, and off we went [to Rockwell’s studio].” The first thing Rockwell said to them was, “We’re going to mess up Mary’s hair,” and with that he tousled her tidy braids.

The first six scenes were completed that first day. For this flying out the door on her way to go swimming look, her mother had to hold her pigtails back, while someone else pulled back her swimming cap. When the angles were just right, “Rockwell would yell, ‘Get it!’” Mary says, and Pelham would snap away.

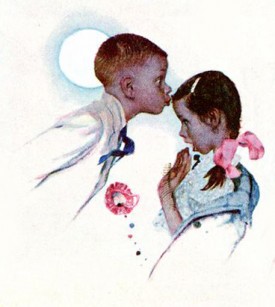

The scene below depicts the old story: Boy meets girl, boy tries to drown girl, spunky girl bawls him out, and then gives him a taste of his own medicine. Ah, young love!

The boy in the love story is Chuck Marsh, another model with a wonderfully expressive face. He was in the earlier Rockwell cover, A Day in the Life of a Boy.

In real life, Mary tells us, she and Chuck never posed in a pool—it was all done in the studio. And when we asked about the dripping wet hair, Mary gave us a glimpse into the glamorous world of modeling: “They poured a bowl of water on me.”

The kids never pushed each other’s heads down either. “We used a bronze bust to lean on … to get the elbow right,” Mary reveals, then adds, “I went to the Rockwell Museum three or four years ago, and they still had that bust in his studio!”

[You can tour the artist’s studio at The Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, or take the online tour here.]

Gradually, boy and girl become friends, go for a bike ride and a movie, and then we find them at a birthday party. In this scene, Mary is wearing a party dress Rockwell bought for her. But what sounds like an act of kindness was most likely the artist’s insistence on just the right details. As an example, he shopped several furniture stores for the exact chair he wanted for his delightful Easter Morning cover from 1959.

The party scene involved more models, including Mary’s twin brother, Peter; and Chuck Marsh’s little brother, Donnie, whose mission was simply to devour the cake and ice cream. Donnie’s single-mindedness about the treats made for a difficult day’s shoot, Mary recalls.

Ten-year-old Chuck Marsh noted that this scene was the “toughest time” he ever had posing. He liked Mary very much, but no how, no way was he going to kiss a girl. “Mr. Rockwell finally gave up trying to get me to kiss her,” he said, and the artist posed the two separately. Getting the smooch just right involved Chuck leaning toward—you guessed it—that bronze bust. Who knew the head of a Classical figure could be so utilitarian?

At the end of this long day, Mary is dressed for bed and writing in her diary, no doubt about that moonlit kiss. And the painting is almost complete.

But there was a problem when Rockwell reached his final scene. With the deadline almost upon him, he remembered the many complaints he had received about one aspect of A Day in the Life of a Boy—before retiring for the night, the boy did not say his prayers. So Rockwell called the Whalens and said, “You’ve got to get Mary down here!”

Because the prayer scene was added, another scene was taken out, Mary tells us. Deleted was a charming scene of Mary and Chuck smiling and thanking their hostess (the birthday girl in the pink hat in the party scene above). But the day is done, bedtime prayers said, and Mary drifts off to sleep with a smile on her face and a party favor beside her.

Previous: Rockwell’s Favorite Model

Next: The third and final installment of Rockwell’s Favorite Model, featuring a coming-of-age cover many feel is one of the artist’s finest works.

Classic Art: Growing Up with Rockwell

Melinda Pelham Murphy, a daughter of Norman Rockwell’s photographer Gene Pelham, grew up around Rockwell’s studio. She talks about being a Rockwell model and the artist’s famous chair and offers a fond remembrance of Rockwell’s wife.

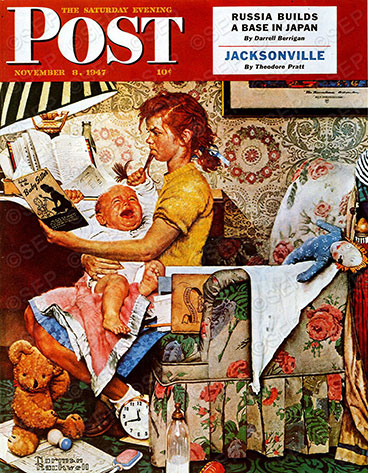

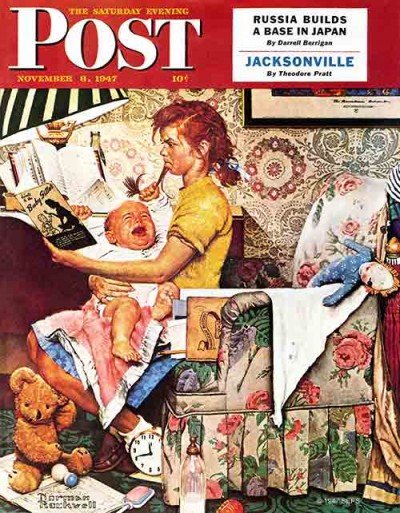

The Babysitter

The Babysitter

Norman Rockwell

November 8, 1947

We would like to say that no babies were harmed in the making of this classic Rockwell cover, but the baby may disagree. During Melinda’s first modeling job, as the crying infant in The Babysitter, the artist and photographer couldn’t get her to cry, so someone stuck her foot with a pin. “My mother told me she always felt terrible about that, but it was what it was.”

“Obviously I was too small to remember anything,” she says. “But somewhere I have a photograph of me that Dad took … and I can see my mother’s image. She’s standing and I’m looking at her, and I am sort of looking sad like, ‘Oh, help me!’” Like many illustrators of the period, Rockwell began by painting live models. But around the mid 1930s, he used photography to capture the scene he would sketch out for a painting, calling the model back if necessary.

The Babysitter shows Rockwell’s ability to capture a dizzying array of details, making it one of those paintings where viewers may pick up something new each time they look at it. And still Melinda brought a fresh detail to our attention: “There’s a pin, an actual pin in the painting. The pin is in the diaper that’s hanging over the chair. He put it right through the canvas, he didn’t paint that in there.” It’s a delightful bit of Rockwell whimsy we were unaware of. Melinda has another viewpoint: “When I found out that I was stuck by a pin and I look at that painting, I wonder if that was the pin that did the deed and then he put it in the picture,” she says, laughing.

Despite the prickly offense, Melinda has a good sense of humor about the situation. In fact, she says she (along with the model baby sitter, Lucille Towne Holton) got involved in keeping the painting where the artist wanted it to be. Rockwell gave the original to the sixth graders of Taft Elementary in Burlington, Vermont, in memory of a student who died of leukemia. The school closed in 1978, and the painting was stored in a local bank. In 1995 appraisers determined it would be worth about $300,000. This was welcome news to the cash-strapped school system, which considered an auction. Former classmates protested and were offered an alternative: raise $300,000 and the painting would remain in town. Many townspeople got involved, and Melinda reports, “We raised the funds and it stays forevermore! It’s at the Fleming Museum; and every time my granddaughter goes there, she says, ‘That’s my grandmother!’ She gets a kick out of it.”

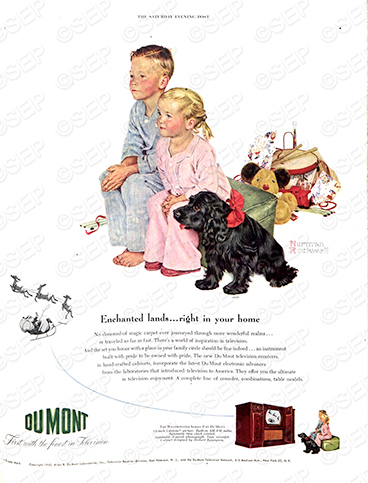

Rockwell Ads

Du Mont TV Ad

Norman Rockwell

December 9, 1950

We first saw Melinda on a recent episode of Antiques Roadshow, where she was having Rockwell artifacts appraised, including a print of this 1950 Du Mont TV ad featuring her at about age 5. The print was accompanied by a note addressed to her father: “…to reimburse your daughter for the long session of posing. Give her my thanks for helping me out. Sincerely, Norman.” We called to ask her about her memories of the artist.

“I do remember him! I remember very well,” Melinda says, although she was only about 5 or 6 when he moved away from her small town in Vermont. “My sister always says to me, ‘I don’t know how you remember all that, I don’t remember these things.’ Maybe I just paid more attention or maybe I just have a different brain. And my sister didn’t pose for him that often.”

What she remembers was a kind man with a fondness for Cokes. This was a treat because soft drinks were limited to “special occasions” at home. But Rockwell had a Coke machine and the models could help themselves on breaks.

Melinda also recalls that Rockwell was particular about the pose he wanted for this ad. “He was very detailed in the way he wanted you to sit,” she says. And sit she did, for 15 hours. The time “would be broken up,” Melinda says, “so he might be working with the boy or the dog, and they didn’t need me” for a while. She remembers the artist’s wife Mary Rockwell who “would take me into the house so I wasn’t just sitting in the studio all that time. She was great about leaping into the breach. I can remember getting a dish of ice cream.”

“It was a long day,” Melinda says, “but Mary took me on a walk. I remember we walked down the back road, and it was a dirt road that ran along the river. And I remember picking ferns with her and then we went back to her garden and got some zinnias.” Melinda’s mother was laid up with an injury at this time, “and I brought her home this bouquet of flowers that Mary had ‘helped’ me put together. She did it all herself, I was very small, but I remember picking the ferns. She was really very sweet. She was a lovely lady. I have very fond memories of being there as a child.”

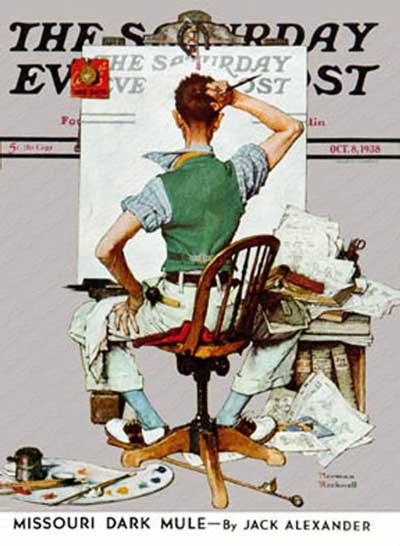

Blank Canvas

Blank Canvas

Norman Rockwell

October 8, 1938

Painting and drawing appraiser Alasdair Nichol was a bit surprised when Melinda also brought a chair to his table at the Antiques Roadshow, suspecting she had been sent to the wrong area. But when Melinda explained that the chair had belonged to Norman Rockwell and had been depicted in the iconic 1938 cover we see here, he understood. Rockwell’s photographer, Gene Pelham (Melinda’s dad), took the chair after the artist threw it out.

“Dad never threw anything away,” Melinda says. He would salvage discards or “Norman would get these things and say, ‘Here, Gene, take this. I don’t want it.’ Norman was not a hoarder or collector, I don’t think, unless it was something he felt he would need in the long run for paintings—costumes and things.”

But the salvaged chair was special. “To think of the amazing paintings that he did when he was sitting in this chair,” appraiser Nichol said. To see how the cast away chair was evaluated, we have a link to the appraisal, courtesy of the Antiques Roadshow.

Thank you to the Antiques Roadshow for the link to the episode featuring Melinda and to the Norman Rockwell Museum for their assistance in contacting her.

Classic Covers: Happy Birthday, Norman Rockwell!

How did Norman Rockwell (1894-1978) begin painting covers for The Saturday Evening Post? We are celebrating Rockwell’s February 3 birthday with his first three Post covers and the stories of how they came about.

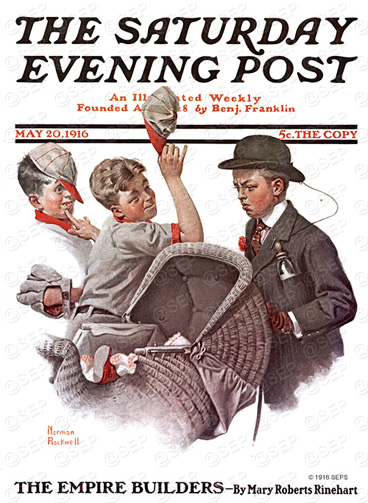

The Baby Carriage

The Baby Carriage

Norman Rockwell

May 20, 1916

In his early 20s, Rockwell was an illustrator and art editor for Boys’ Life magazine. But, according to Rockwell in My Adventures as an Illustrator, he was tired of being accepted only by children’s publications and fed up with seeing “the Rover Boys and their lousy dog with the Mounted Police” on his easel. He dreamed of his art on the cover of The Saturday Evening Post; the thought of having his paintings viewed by millions excited daydreams of being famous: “surrounded by admiring females, deferred to by office flunkies at the magazines, wined and dined by the editor of the Post, Mr. George Horace Lorimer.” But that was the rub. Twenty-two-year-old Rockwell was petrified by the thought of approaching “the baron of publishing” who had “built the Post from a two-bit family magazine with a circulation in the hundreds” to a major publication with millions of readers. He had heard the publisher was tough. What if Lorimer didn’t like his work?

Rockwell had a friend named Clyde Forsythe, a cartoonist who knew his way around the world of commercial art. Forsythe was also straightforward. He was the only person Rockwell knew who wouldn’t just ooh and ah over his work, but would give an honest evaluation. He visited Rockwell one day and found the dejected artist lying on a cot in his studio. He asked Rockwell what was eating him, and Norman “hemmed and hawed but finally told him.” Forsythe’s advice: “‘Stop chewing on your tongue and do a cover. What the hell, you’re as good as anybody. Lorimer’s not the Dalai Lama.’”

So Rockwell did a couple of paintings, both attempts to mimic the high society images the Post favored at the time: one a romantic scene with a debonair pair of lovers in the style of Charles Dana Gibson and the other a beautiful ballerina curtsying under a spotlight. Forsythe returned and denounced them as “‘C-R-U-D, crud,’” noting Rockwell was a guy who just couldn’t paint beautiful women. Then he snatched up one of the illustrations Rockwell had just completed for a story in Boys’ Life. “‘Do that,’ said Clyde. ‘Do what you’re best at. Kids. You’re a terrible Gibson, but a pretty good Rockwell.’”

It was sound advice. On his first meeting with Post Art Editor Walter M. Dower, Rockwell sold two paintings (The Baby Carriage and The Circus Strongman) and had three sketches for future covers approved (including Gramps at the Plate). Though his work had been OK’d by Lorimer, Rockwell had yet to meet the publisher; instead it was Dower who informed him that he would receive $75 for each cover. Rockwell’s monthly salary as art director and illustrator for Boys’ Life was $50; he was over the moon. His first cover The Baby Carriage appeared on May 20, 1916.

(The story above was adapted from My Adventures as an Illustrator by Norman Rockwell.)

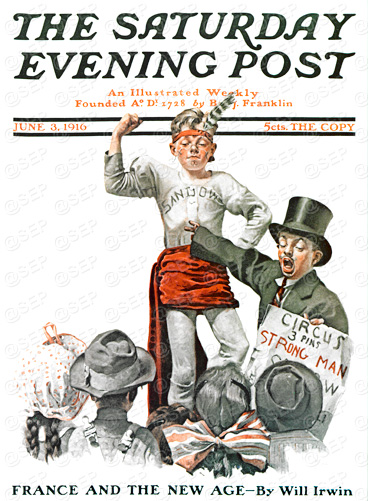

The Circus Strongman

The Circus Strongman

Norman Rockwell

June 3, 1916

1916 was something of a golden year for America. The economy was good and it was the last year before the U.S. entered into World War I. And boys dreamed of becoming the great strongman, Eugen Sandow. Showman Florenz Ziegfeld made a star of Sandow, who would lift weights, pose, and even break chains across his chest for audiences. Edison Studios did a short film of Sandow posing and flexing. This was the stuff of dreams for young boys.

Posing children would be a challenge to any artist, and getting a child to maintain a pose long enough to sketch the scene was difficult. But Rockwell had a way of dealing with the restlessness. At the beginning of each modeling session with kids, he set a stack of nickels on a table next to the easel. Every 25 minutes, he would take 5 nickels from the stack and set it aside, telling the model, “Now, that’s your pile.” Five cents in 1916 would be about a dollar in today’s money, and watching the coins pile up was great motivation. The model for “Sandow” was Billy Paine, who posed as all three boys in The Baby Carriage above. Rockwell used Paine in several Post covers. Sadly, Paine died at age 13; he’d been horsing around a second-story window and fell. “He was the best kid model I ever used” Rockwell said.

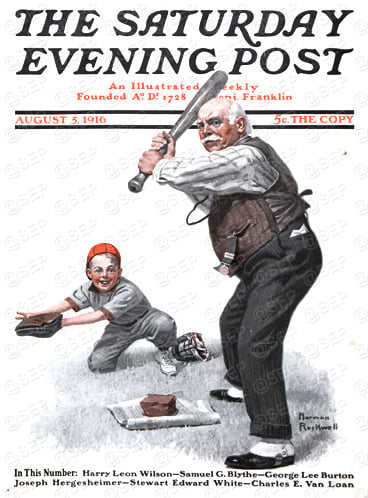

Gramps at the Plate

Gramps at the Plate

Norman Rockwell

August 5, 1916

The young artist still hadn’t met the powerful publisher, George Horace Lorimer, but was dealing with Walter Dower, the art editor. Rockwell’s first two finished paintings were accepted without any changes, but when Rockwell submitted his third painting—the baseball-playing grandfather—he found out being a Post cover artist wasn’t so easy after all. In My Adventures as an Illustrator, Rockwell tells the story of this cover:

“Mr. Dower brought word out that Mr. Lorimer thought the old man was too rough and tramplike. Would I do the painting over? Of course. I stretched a new canvas and began again. ‘Better,’ said Mr. Dower. ‘Mr. Lorimer thought it was better. But the old man’s too old, he thought.’ I did the painting over again. The boy was too small. I did that painting over five times before Mr. Lorimer accepted it.”

Later, Lorimer informed Rockwell that he had been testing him. Why? To test the new artist’s versatility, his ability to take direction, his perseverance, or maybe just to see if Rockwell would do his bidding. Whatever the reason for the test, the ordeal almost caused the young artist to give up: “I wonder if he ever knew how near I came to flunking his test.”

Classic Covers: The Family Rockwell

My Three Sons is not only the title of a 1960s sitcom starring pipe-toting Fred MacMurray; it’s also a fitting title for the story of one pipe-toting artist, Norman Rockwell. His three boys—Jerry, Tom, and Peter—showed up on the cover of The Saturday Evening Post more than half a dozen times.

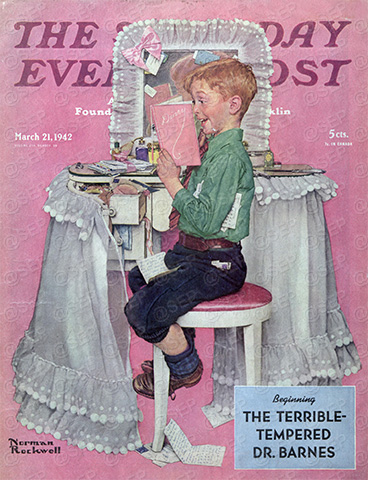

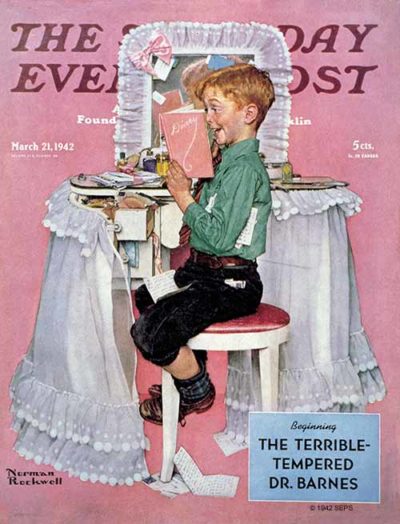

Devil May Care

Devil May Care

Norman Rockwell

March 21, 1942

Half of the 52 Post covers in 1942 were war-related: soldiers in action, girlfriends waiting at home, and so on. So this cover (left) was a special treat for two reasons. First, it was humorous and fun, and second, it was by America’s favorite artist. When Rockwell did a cover, thousands of additional issues were printed to meet the demand.

Rockwell sometimes used neighbors’ homes for the settings of his paintings. In a 1976 Post article, former Rockwell model Ann Morgan Baker (see The Missing Tooth in “Rockwell in the 1950s—Part I”) recalled that the artist “used to call my mother at 7 a.m. and say, ‘Don’t make the beds. I want to come and look at some messy rooms.’ Then he would come and wander through our morning rubble.”

Because Rockwell did not have a daughter, he probably used such a neighbor’s home to find this vanity with all the frills. Reportedly, middle son Tommy had to be bribed to pose for this 1942 cover, although it was noted that the mischief-maker was just the kind who would have read his sister’s diary—if he had a sister, that is.

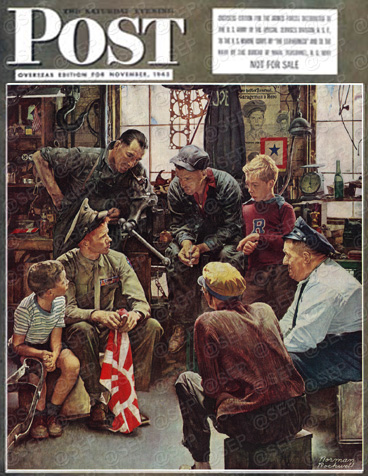

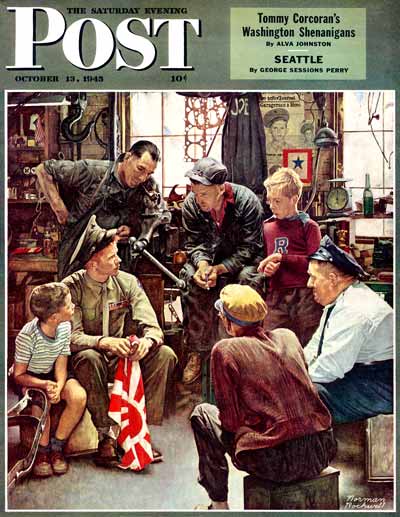

War Stories

War Stories

Norman Rockwell

October 13, 1945

Norman Rockwell’s World War II covers were usually light and humorous, like the ones in his Willie Gillis series. A very fine exception to this was the serious depiction of a returning marine sharing his experiences at left. There is no bravado; no showing off. The grim reality of war permeates the gathering at the local garage.

As Rockwell’s life is well documented, we know most of the models in the garage are the artist’s Arlington, Vermont, neighbors and friends, including the actual shop owner, Bob Benedict (standing behind the marine). Sitting beside the marine is Rockwell’s youngest son, Peter. The blond boy standing up is Jerry, his oldest. The decorated soldier was real-life marine Duane Parks, whom Rockwell met in a nearby town. At times, uniform medals and ribbons were borrowed to dress up a scene, but the military decorations shown here belonged to Parks.

Rockwell enthusiasts will appreciate the artist’s attention to detail in this 1945 cover. In addition to the usual machine-shop equipment: gaskets, the large hook, etc., he included the Japanese flag; the newspaper clipping on the shop wall, which declares the marine a war hero; and the small flag with the blue star representing a family member serving in the armed forces. We see these starred flags not only in Post covers of the period, but also, for example, in movies. In Saving Private Ryan, Ryan’s mother has such a flag. A star was added for each family member in service; the blue signaled hope, and a gold star meant a loved one had died in service.

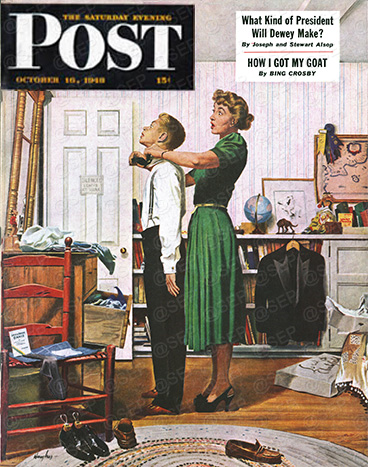

Readying for First Date

Readying for First Date

George Hughes

October 16, 1948

The young man at left getting ready for his big date is Tommy Rockwell, who is looking quite grown up compared to the little sneak he portrayed for a cover six years earlier (see Devil May Care, above). Tommy’s actual room in Arlington, Vermont, is the setting, and the woman giving him a hand is his real-life mother (Rockwell’s wife Mary). However, the artist of this domestic scene is not whom you’d expect. It’s Rockwell’s good friend George Hughes, who had moved to Arlington to join the small community of Post artists there. The artists often used the same neighbors, their families, and each other as models.

Hughes, though less well known than Rockwell, was the most prolific Post cover artist of this era—he produced 80 covers in the 1950s to Rockwell’s 45—and he had an unintended influence on one of Rockwell’s classic covers, Saying Grace (below).

Saying Grace

Saying Grace

Norman Rockwell

November 24, 1951

Intrigued by a fan’s description of an Amish woman and her grandson praying together in a cafeteria, Rockwell painted what is now one of his best-known works, Saying Grace (left). But this painting came very close to being abandoned before it was completed.

Rockwell told fellow Post artist George Hughes that he got so frustrated with the painting he threw it out his studio window, according to a 1992 article in the Post. When Hughes asked the theme, Rockwell described it as centering on several rough-looking fellows watching a woman saying grace in a diner. Hughes agreed it would never work. That comment was all it took to get Rockwell started again. He retrieved the painting from the snow and completed it. This became a long-running joke between the two artists: Rockwell would solicit Hughes’ opinion and then do the opposite.

The blond diner with his back against the window is Rockwell’s son, Jerry, looking much older than he did on the 1945 cover War Stories (above). On a sad note, the woman bowing her head, May Walker, did not live to see the cover; she passed away five days before it was published. Although she didn’t have the pleasure of enjoying the stir among her Arlington, Vermont, neighbors over her newfound fame, Rockwell assured Post editors that she derived a great deal of pleasure from the experience. When the painting was done, Walker was brought to Rockwell’s studio to view it. People who knew her well told the Post “her enjoyment of that day was one of the high moments of her life.”

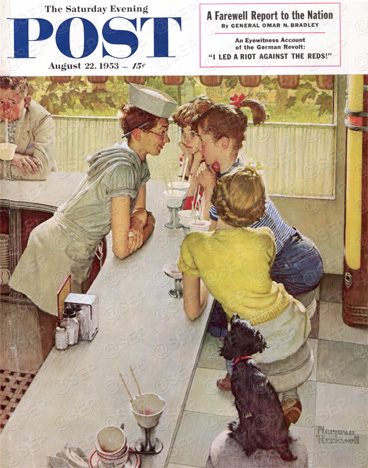

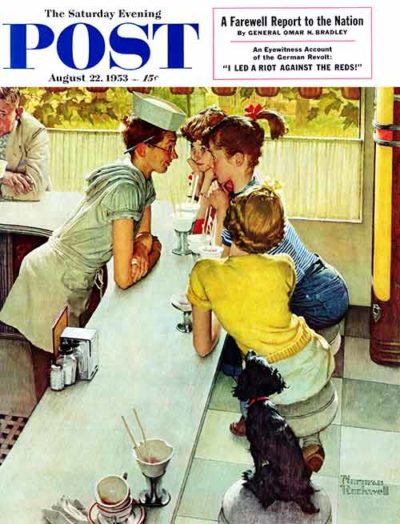

The Soda Jerk

The Soda Jerk

Norman Rockwell

August 22, 1953

In his first attempt at this 1953 cover (left), the artist had painted a man in the immediate foreground and a woman with her son at the other end of the counter. He decided these people cluttered and confused the scene. Painting it again, Rockwell focused the attention on a teenaged soda jerk and his female admirers.

The idea came after Rockwell listened to his youngest son Peter’s tales of his summer soda-fountain job. Peter posed as the soda jerk, but he didn’t care for the finished painting. “I’m not that goofy-looking,” he said. Peter Rockwell appeared on the War Stories cover (above) and in Second Thoughts.

Today Peter Rockwell is a sculptor living in Italy and discusses his art in this video, courtesy of the Norman Rockwell Museum.

The Homecoming

The Homecoming

Norman Rockwell

December 25, 1948

The Homecoming at left is one of the great Rockwell covers featured in our special holiday issue, Norman Rockwell A Very Magical Christmas!. And it is magical indeed when an absent family member comes home for the holidays. All three of Rockwell’s sons are there—although we only see the back of his oldest son, Jerry, who is receiving a joyful hug from his mother Mary. To the left of Mary is son Tommy in the plaid shirt and to the far left is youngest son Peter wearing glasses. To Mary’s right, with that ubiquitous pipe, is America’s favorite artist, who enjoyed the occasional cameo in is own paintings (See “Rockwell Paints Rockwell”).

A family gathering needs a grandmother, and happy to pose for the role was none other than Grandma Moses. Rockwell wrote of Moses in his 1979 book, My Life as an Illustrator:

“After the war I became acquainted with Grandma Moses, the famous painter of American primitives. She had started painting seriously at the age of 67 after the death of her husband. Using dime-store brushes and house paint, she did scenes of country life which she remembered from her childhood.” Noting that she would do paintings of someone’s house for $10 or $15, Rockwell continued, “When I knew her, she was over 85 years old, a spry, white-haired little woman. Like a lively sparrow. She still painted in her bedroom on the third story of her farmhouse, using the same cheap brushes and house paint, though the paintings were selling rapidly for very good prices.”

The rest of the homecoming crowd consisted of Rockwell friends and neighbors, including the “twins” in the red jumpers—both were actually one little girl named Sharon O’Neill, whom Rockwell painted twice.

Rockwell: The War Years

“War Stories”

“War Stories”

from October 13, 1945

A number of Rockwell Post covers have become iconic — classics we all recognize right away. Some of the wartime covers we show you here may be some of the illustrator’s finest work, yet they are seldom seen. We view them this Memorial Day weekend to honor those who have served and those who serve today.

“War Stories”

“War Stories”

from October 13, 1945

A war hero, holding a Japanese flag, has tales of war to tell, and clearly the memories are not light, the retelling not boastful, and the life-altering experiences he relates are riveting. The news article on the wall shows that the soldier is a local hero. The model was not a former garage employee, but was indeed a decorated Marine named Duane Parks. Rockwell found him in Dorset, Vermont. The other models were, as usual, Arlington, Vermont neighbors of the artist. The man with the pipe leaning in to listen was the owner of the garage, Bob Benedict. The man posing as the policeman was Arlington town clerk and newspaper editor. The young boys Rockwell found even closer to home: the boy sitting next to the Marine was his youngest son, Peter, and the blond boy to the right was his oldest son, Jerry. They, along with brother Tommy, appeared on many a Rockwell canvas.

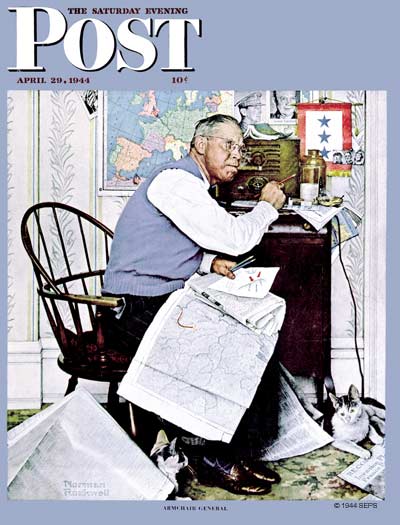

“The Armchair General”

“The Armchair General”

from April 29, 1944

Tracing each advance and retreat is more than an interesting pastime with this gentleman. The service flag with three stars indicates he has that number of sons serving. May the stars remain forever blue, for a gold star represents a serviceman who will not return home. With his customarily remarkable eye for detail, Rockwell shows a tiny photo of each boy by the flag, photos of generals MacArthur and Eisenhower, a wall map, and an old-fashioned radio.

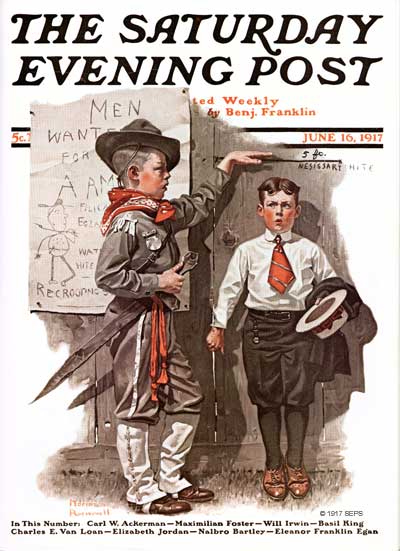

“The Clubhouse Examination”

“The Clubhouse Examination”

from June 16, 1917

Going back to 1917, Rockwell shows us a different kind of “recruitment center.” Even on tiptoe, our would-be soldier doesn’t measure up to the “nesissary hite.” The “recrooter,” decked out in a combination scout/soldier attire, was one of Rockwell’s favorite early models, Billy Paine. Alas, boys sometimes do foolish things in real life and Paine died at age thirteen doing a stunt from a second-story window. He was in fifteen Rockwell Post covers.

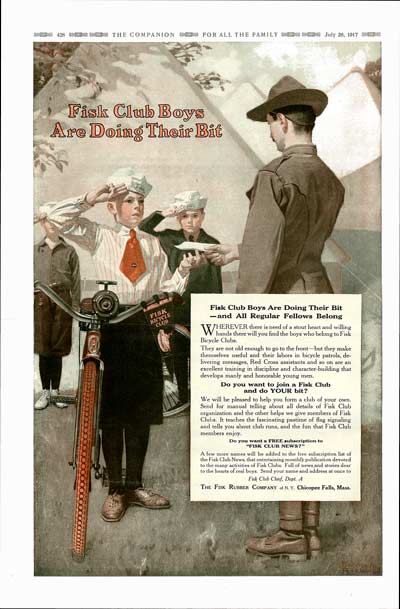

“Fisk WWI Soldier – Youth’s Companion” by creator

“Fisk WWI Soldier – Youth’s Companion”

from July 26, 1917

We found a couple of boxes of a publication called The Youth’s Companion in the archives recently. This was a children’s magazine published in Boston from 1827-1929. By happy accident, we noticed this Rockwell ad for something called “Fisk Boys Club” from a 1917 issue. Rockwell numbered Fisk Tires among his many advertising clients. What was the Fisk Boy’s Club? It was a way for youngsters to participate in the war effort:

They are not old enough to go to the front–but they make themselves useful and their labors in bicycle patrols, delivering messages, Red Cross assistants and so on are excellent training in discipline and character building that develops manly and honorable young men.

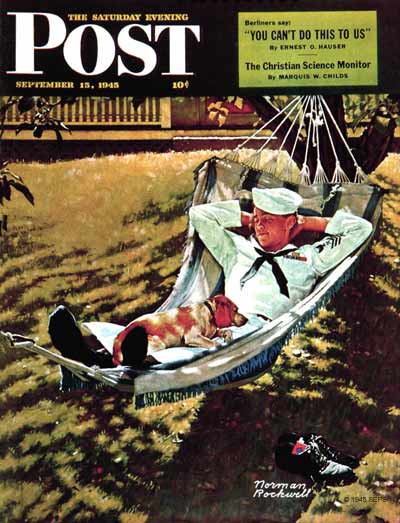

“Home at Last”

“Home at Last”

from September 15, 1945

Back to post-WWII for a restful snooze in a hammock on a quiet, sun-dappled afternoon — who could wish for more for our loved ones returning home?

Rockwell was a borrower for this painting. He borrowed the sailor, soon to return to the Navy, from Williams College. The sailor’s uniform was borrowed from a shipmate, as he didn’t have the decorations on his own. The house was borrowed from a neighbor; the hammock from another neighbor. Rockwell borrowed the pooch from his son, Tommy. The shoes were not borrowed however — they belonged to the artist.

Escape Artist

What budding artist hasn’t felt the terror of exposing his or her work to the world at large? This painting depicts a young artist, canvas in hand, fleeing a rural rainstorm. But as is often the case with a Norman Rockwell painting, there’s a story behind the canvas.

As it happens, Rockwell was vacationing in the hamlet of Louisville Landing, New York. While out for a stroll, he noticed his neighbor’s granddaughter Elizabeth painting a landscape of the surrounding farm. Rockwell walked over to take a look, but when Elizabeth saw him coming she recognized the famous illustrator in his trademark white bellbottom pants and holding his signature pipe. The chance encounter with celebrity was too much for the young woman, who fled in embarrassment rather than have her labors exposed—and possibly critiqued. She picked up her artwork and supplies and “high-tailed it out of there,” as she would say years later.

Rockwell was sorry about frightening her, but a conversation with her father about his shy, artistically inclined daughter cleared the air. The conversation also afforded Rockwell an opportunity to ask permission to paint Elizabeth for a Post cover.

Although bashful, Elizabeth knew how impressed her friends would be seeing her on the cover of the most popular magazine in the country. So, overcoming her hesitation, she agreed to meet with Rockwell.

The next day Elizabeth stood nervously in front of Rockwell’s cottage. Suddenly he opened the door, startling the faint-hearted girl who once again turned and bolted from his front yard. The painting of the painter was not to be!

Disappointed, Rockwell never forgot about the touching scene. Ten years later in southern California his vision finally came to fruition when he painted his new fiancée’s neighbor and cousin, Rosemary, as the shy artist from Louisville Landing running with a painting of her grandfather’s field.

This story is dedicated to Elizabeth, the original inspiration for “Wet Paint,” the cover shown here. She very graciously shared her memories of Rockwell with me a couple of decades ago. Elizabeth passed away in July of 2010 at the age of 101.

Classic Covers: Rockwell Kids of the ’40s

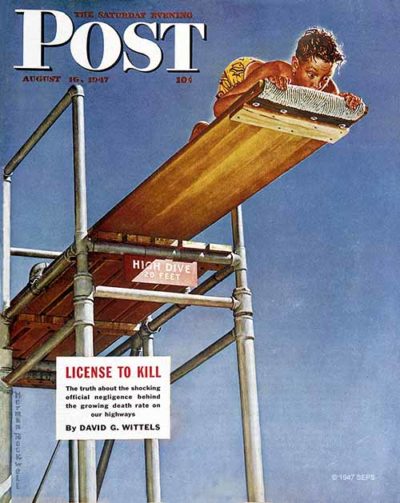

“Second Thoughts” from August 16, 1947

“Second Thoughts”

August 16, 1947

Norman Rockwell painted many Saturday Evening Post covers featuring kids in everyday situations, beginning in 1916. Still going strong in the 1940s, the artist remained a master at capturing youth.

“Second Thoughts” from August 16, 1947

“Second Thoughts”

from August 16, 1947

Striving for realism, Rockwell took a long board and stuck it out of a second story window. Then he told son Peter, “I want you to crawl out onto that board and look scared.” Rockwell models became adept at acting a part. Peter was not acting; he was terrified.

“We’re all on diving boards, hundreds of times during our lives,” Steven Spielberg said in a 2010 article in The Oregonian. “Taking the plunge or pulling back from the abyss…is something that we must face. For me, that painting represents every motion picture just before I commit to directing it—just that one moment, before I say, ‘Yes, I’m going to direct that movie.” Hmm, maybe we should all have this one on our walls.

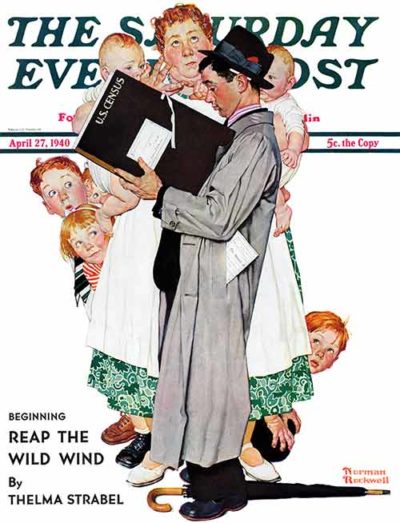

“The Census Taker” from April 27, 1940

“The Census Taker”

from April 27, 1940

In 1790 the U.S. Government decreed that a census be taken every ten years to keep track of the ever-populating land called America. In 1940, this census taker shows up with his big black book to interview an ever-populating housewife. She appears to be much like the old woman who lived in a shoe, with so many children she didn’t know…how to recall all their birth dates. Or perhaps she’s even trying to remember just how many cute little red-haired moppets there are!

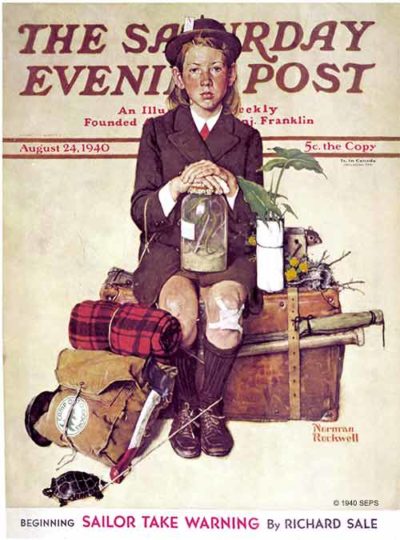

“Home From Camp” from August 24, 1940

“Home From Camp”

from August 24, 1940

Just as they do today, droves of youngsters in the 1940s made their way to camps for an outdoor adventure. This particular one came home with everything except the cabin, making it a perfect vehicle for Rockwell’s passion for detail. She seems sad to leave the friends she made and get back to real life, where it remains to be seen if Mom and Dad will go along with the critters she collected.

“Devil May Care” from March 21, 1942

“Devil May Care”

from March 21, 1942

Rockwell and his wife were not blessed with girls, so the artist must have located a young lady’s vanity among his neighbors. The background is even pink to emphasize that this is girl territory. Rockwell did have three boys, however, and this was one of them. If young Tommy Rockwell did have a sister, no doubt the little scamp would be having a ball sneaking a peek at her diary for the juicy stuff.

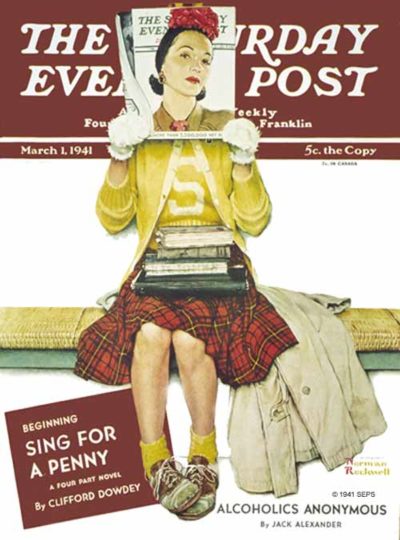

“Cover Girl” from March 1, 1941

“Cover Girl”

from March 1, 1941

People often call after finding old issues of the Post, thinking they’ve uncovered a gold mine. They often forget that for many decades, it was printed by the millions, and then the would-be nouveau riche take our advice and troll the Internet for sites that sell vintage magazines. They are disappointed to find an issue they thought was old (1940s, for example) may go anywhere from $4.95 to $25.00. On occasion, up to $75.00. With the exception of this issue.

Sure it has an adorable Rockwell cover, but that isn’t why this is the most sought-after issue of the Post. If you can find it, be prepared to pay over $1,000 because of its rarity. And the rarity is because of the groundbreaking Jack Alexander story, “Alcoholics Anonymous.” AA had been showing striking success in the past six years (since its founding in 1935) in achieving sobriety for the “medically helpless.” Thousands of reprints were requested and the article was key to spreading the idea that alcoholism is a disease rather than a character flaw. (Read more about the “Alcoholics Anonymous” article here.)

Groundbreaking story and issue rarity aside, back to our man Rockwell with his Saturday Evening Post cover-within-a-Post-cover. Leave it to Norman to show how yellow socks and scuffed oxfords contrast with perfect make-up and a sophisticated chapeau.

Rockwell Classics from the 1940s

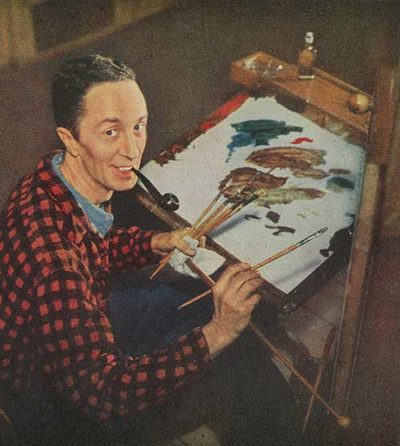

Norman Rockwell “the Artist” – February 13, 1943

Norman Rockwell the Artist

From February 13, 1943

This photo of Rockwell appeared in the Post in 1943. By this time, the man at the easel had been doing Saturday Evening Post covers for twenty-seven years. The forties were a time of humor, anguish, the workplace, and kids being kids. This week: 1940s classics.

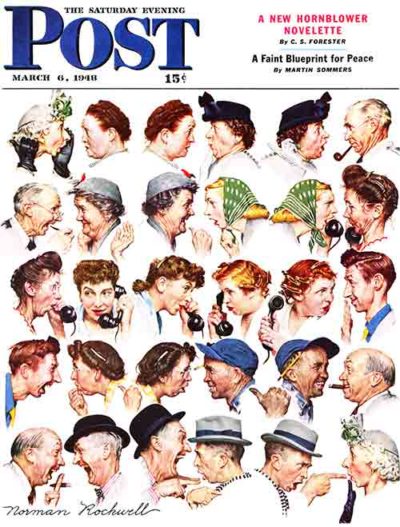

“The Gossips” From March 5, 1948

“The Gossips”

From March 5, 1948

A great illustration tells a story, and we all know this tale. Don’t you hate when someone starts a rumor about you? Well, it happened to Rockwell and he didn’t like it one bit. But he had a weapon: a paintbrush and a platform viewed by millions: The Saturday Evening Post cover spot.

It’s fun to look at the expressions: some appalled, some relishing the scandal. Afraid he might offend his neighbors/models (love the lady in curlers and the guy in the bowler hat), Rockwell included his wife and himself among the rumor spreaders. Mary Rockwell is second and third in the middle row and Norman is at the end, first with a “Who? ME?!” expression, then giving what-for to the lady who started it all.

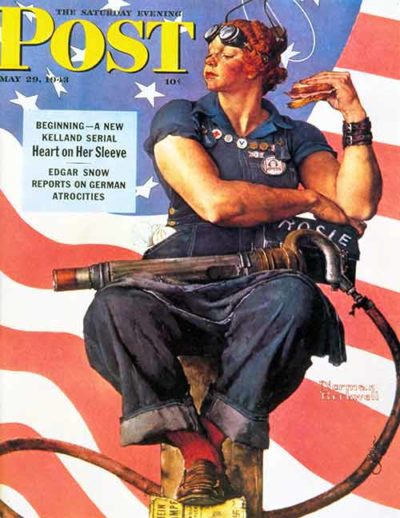

“Rosie the Riveter” From May 29, 1943

“Rosie the Riveter”

From May 29, 1943

We’ll review Rockwell’s covers from the war years soon, but for now—what can be more classic than Rosie the Riveter? With the men fighting the war, women had to step up to the plate and keep factories, farms and offices going at home and this gal looks more than capable. She may have a dirty face, muscles and a crushed copy of Hitler’s “Mein Kampf” under her sensible shoe, but she’s still a girl at heart. A compact and ladylike hanky peak out from one pocket.

“The Babysitter” From November 8, 1947

“The Babysitter”

From November 8, 1947

No babies were harmed in the creation of this cover. In fact, the baby was too darned happy. After some search, Rockwell borrowed a big, strapping baby boy to paint from a neighbor. The artist wanted a big lusty wail, but Post editors inform us that “the baby was as good-natured as a kitten full of milk; he wouldn’t even frown.” The babysitter sat and waited. The artist sat and waited. They gave the boy a cookie and the uncooperative little sod was happier than ever.

Eventually, the tot dropped the cookie and let out a brief yell. Ready with his camera, Rockwell got the shot and had a photo of a squalling kid to paint from so he could finish his artwork. It was the only peep they had out of the baby the whole time.

This is a prime example of Rockwell’s enthusiasm for detail. The attention to the minutiae of the chair pattern and wallpaper is almost enough to make the viewer dizzy. It is easy to miss items like the open geometry book and soft drink the beleaguered lass may never get back to by the lamp. And ever the storyteller, the artist shows us that nearly everything has been tried: rattles, a bottle, a bear, a doll, a coloring book. Let’s hope her booklet, “Hints to the Babysitter,” has something useful to offer—and soon!

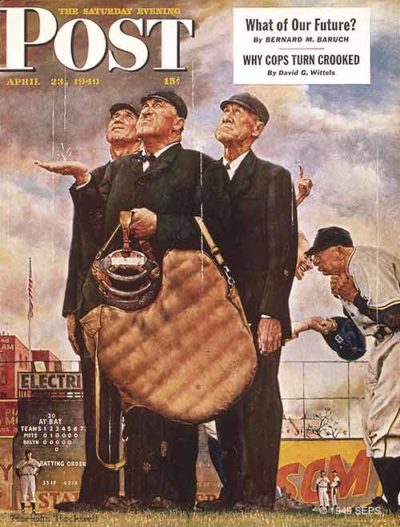

“The Three Umpires” From April 23, 1949

“The Three Umpires”

From April 23, 1949

There is a game riding on the weather-related decision these umpires are making. The Pittsburgh Pirates are ahead 1-0 in the sixth inning. The Brooklyn Dodgers, at home here at Ebbets Field, stand to lose if the game is called on account of rain.

Post editors speculated on the conversation between the guys to the right. They figure Brooklyn coach, Clyde Sukeforth, pointing at the sky, is declaring, “You may be all wet, but it ain’t raining a drop!” Whereas the huddled figure of Pittsburgh manager Bill Meyer is probably saying, “For the love of Abner Doubleday, how can we play ball in this cloudburst?”

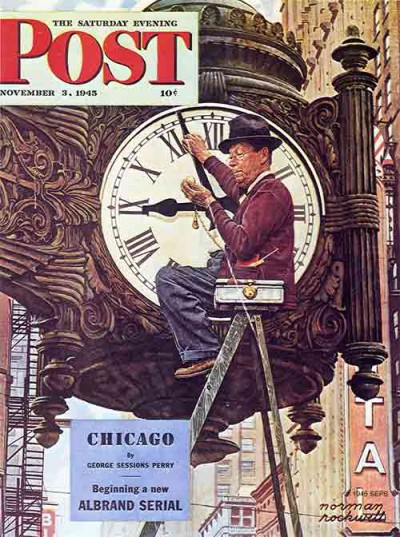

“The Correct Time” From November 3, 1945

“The Correct Time”

From November 3, 1945

The giant clocks at what was then Marshall Field and Company in Chicago suggested a cover idea to a visiting gentleman named Rockwell. The two massive bronze clocks were electric and controlled by a master, so it was only after a power outage that a workman had to get out the tall ladder, climb the 17 ½ feet and set the hands. It is probably artistic license that this gent is synchronizing the time with his trusty old pocket watch.

For many years, Chicagoans have depended on the time display as they scurry back and forth. Apparently, they weren’t the only ones. To the left and above the 9, Rockwell suggests that the intricate scrollwork was also convenient for birds to build nests.

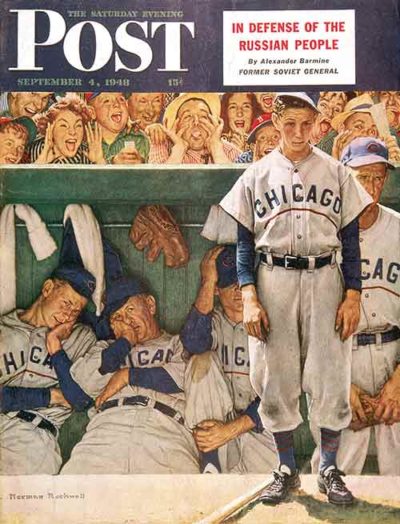

“The Dugout” From September 4,1948

“The Dugout”

From September 4,1948

Rockwell wasn’t the only artist to paint memorable baseball covers. John Falter’s wonderful cover of Stan the Man and others can be seen in “Great Post Baseball Covers.” But “The Dugout” from 1948 has to be one of Rockwell’s classics. It wasn’t a good year for Chicago baseball, with both the Cubs and the White Sox having a dismal season. This Post cover did nothing to boost the morale of Windy City fans.

At a game in Boston, Rockwell and a Post art editor strode onto the field and chose people to sit above the Cubs’ dugout. The artist would point to a spectator and contort his face into a gleeful or disgusted look asking the fan to emulate him while a photographer snapped them. Later, Rockwell would paint them in, raspberries and all. The happy ones were, not surprisingly, Braves fans: the delighted woman to the left was the daughter of a Braves coach and the lady clutching her hands a few faces over was the wife of a Boston pitcher. (Yes, in 1948, it was the Boston Braves, before they became the Milwaukee Braves, and eventually, the Atlanta Braves.) The Cubbies were actual players (and their manager, second from left in the dugout, living up to his name: Charlie Grimm) and this was an actual Sunday afternoon double header.

Rockwell in the 1950s – Part III of III

“The Soda Jerk” – August 22, 1953

“The Soda Jerk”

From August 22, 1953

Perhaps it’s the prestigious position of being a soda jerk, but these young ladies are clearly not just there for the ice cream. Rockwell’s three sons often posed for his paintings, and this babe magnet is Peter, his youngest. In fact, the artist got the idea for this cover while listening to Peter talk about his summer job at a soda fountain.

Tthere is Rockwell’s attention to detail: the non-slip wooden floor behind the counter, the dishes that should have been cleared, even the reflection of the salt and sugar containers in the chrome of the napkin holder. A chubby guy at the counter looks on enviously, thinking, “what does he have (besides ice cream) that I don’t have?”

Alas, every artist has his critics. Peter wasn’t thrilled with the result, saying, “I’m not that goofy-looking.”

“Happy Birthday, Miss Jones” – March 17, 1956

“Happy Birthday, Miss Jones”

From March 17, 1956

Anne Braman, from Rockwell’s hometown, posed for this tribute to the schoolteacher in a local classroom. First Rockwell posed the children (love the kid with the eraser on his head, as if he didn’t have time to “straighten up” from mischief before the teacher arrived) and then they were sent to another room where they were given a Coke and a check.

“Then Mr. Rockwell posed me against the blackboard,” Ms. Braman told the Post in 1976. “His late wife, Mary, was present and did not care for the shoes I was wearing at the time, and suggested I put on hers, which were at least two sizes too large for me.” Like other models we’ve reviewed from the 50s, the cover made Anne something of a celebrity. “When I attended my twenty-fifth high school reunion,” she told us, “I was given a prize for being the first member of the class to be a ‘cover girl.’”

But the cover below was Anne’s favorite, for a special reason.

“The Marriage License” – June 11, 1955

“The Marriage License”

From June 11, 1955

It is late afternoon on a Saturday (the calendar even gives us the day), and the elderly clerk has his boots on and would like to get home. Couples in love are a humdrum regularity in this office. By contrast, an excited young couple is happily filling out the paperwork for their marriage license, a momentous occasion they are not inclined to rush. This was a real engaged couple, Joan Lahart and Francis Mahoney, of nearby Lee, Massachusetts. Of the big, handsome groom-to-be, Rockwell said, “You know, this is a self-portrait of myself. At least that is what I would have liked to look like if I had had the opportunity.”

This famous 1955 cover meant a great deal to Anne Braman, who posed as the teacher above. Earlier that year, “my mother-in-law died. Mr. Rockwell, knowing my father-in-law, Jason C. Braman, realized how upset he was and he thought if he could get him to model it would give him something new to think about. Mr. Rockwell indicated he had done this sort of thing in the past when someone had lost a loved one.” Mr. Braman made a fine town clerk.

The famous Rockwell detail is there. You can almost touch the cold iron of the stove (it is June, after all). The artist was very specific about what the young lady would wear, and the bright sunshine yellow of her dress contrasts beautifully with all the dark wood. Add the magnificent lighting from the window, and this may be one of Rockwell’s best covers.

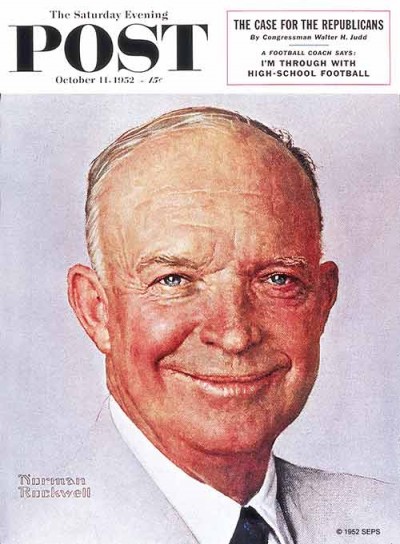

Dwight David Eisenhower – October 11, 1952

Dwight David Eisenhower

From October 11, 1952

Ike was excited to show Rockwell his paintings and get some expert advice. “They were terrible,” Rockwell said. “His stuff was not quite as good as Churchill’s, who was also an amateur artist, you know, but he was a wonderful man. I guess I liked painting him best of all the presidents. Yea, Ike was as comfortable as an old shoe. Maybe that’s why the two of us got along so well.” This was 1952, but four years later, Ike again appeared in a Rockwell cover, as did his opponent, Adlai Stevenson, whom the artist recalled as “amiable, kind, unpretentious, and quietly charming.” Kind of makes it hard to tell which side of the political fence the artist was on, but it is refreshing to hear that both politicians were amiable and unpretentious.

“Rockwell Meets the President” June 11, 1955

“Rockwell Meets the President”

From June 11, 1955

President Eisenhower invited the artist to a White House dinner in 1955. Post editors got word that the artist “was observed galumphing around his home town of Stockbridge, Massachusetts in a new set of shiny black evening shoes” in an attempt to break them in. It was also noted “Rockwell also bought a cummerbund to undergird his tux, and it almost broke in his stomach, but he stayed with it.” Since the editors enjoyed tweaking Rockwell, they ran this cartoon of a spiffy but uncomfortable Norman on his way to meet the President.

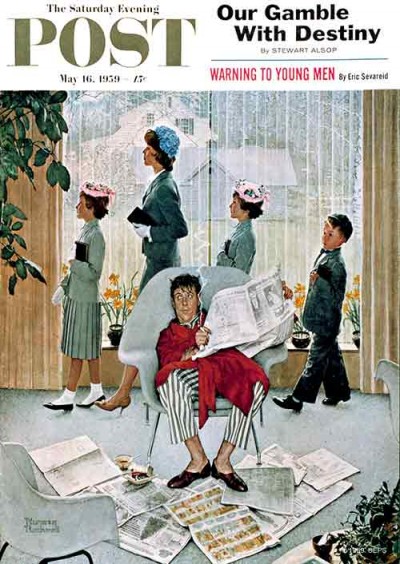

“Easter Morning”

From May, 16, 1959

“Why is papa not going to church—is he ill?” asked the editors of this 1959 cover. “No, his health is sound, except that he is suffering a momentary chill as his family coldly passes by.” Okay, dad really should go to church, but the lure of a comfy Sunday with coffee and the sports pages is stronger than the appeal getting dressed up for a crowded Easter Sunday.

Interestingly, the view outside the window is the exact view outside Rockwell’s studio. On the cutting edge was the sleek Scandinavian furniture—the artist scoured furniture stores for just the right chair. The wife is portrayed by Rockwell’s daughter-in-law, Gail. When the artist was asked if the two young ladies were twins, he replied, “They ought to be. I only hired one model.” Although the “twins” are steadfastly standing by mom, the boy can’t resist a glance at dad, perhaps hoping for a reprieve so he, too, can stay home and relax. If you click on the cover for a close-up, you’ll see the best touch of all: Rockwell gave dad’s tousled hair “horns.”

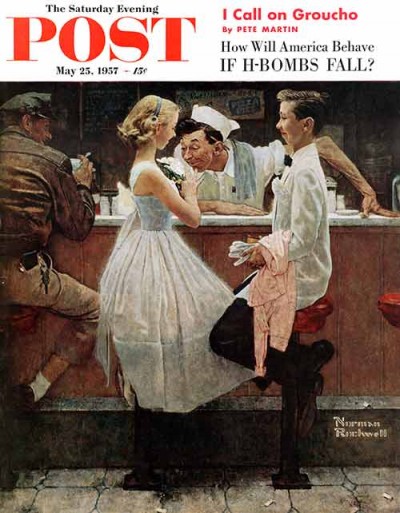

“After the Prom” – May 25, 1957

“After the Prom”

From May 25, 1957

It had to be only yesterday that this stylish young lady was a tomboy climbing trees and the dapper gentleman had a secret clubhouse dedicated to keeping girls out. But tonight she is a fairytale princess proudly showing off her corsage to a gracious footman, and he is an elegant prince. Alas, the corsage and tux rental have put a dent in the royal coffers, and the after-dance caviar and champagne will have to be burgers and soda at the local diner. But it doesn’t matter—they will remember it as if it were Buckingham Palace.

We’ve reviewed Rockwell’s art in the sixties and fifties, which of course leads us to the 1940s—next!

Ouija Does It

Like a novelist, Norman Rockwell had a keen eye for small moments in ordinary life that signified broader trends. One such discovery occurred in the summer of 1919 when Rockwell, his wife Irene, and her family travelled to Potsdam, New York, to celebrate homecoming at Irene’s alma mater, Potsdam Normal School. In honor of his wife, Rockwell illustrated the cover for the special anniversary issue of the school’s alumni magazine—a gift popular with all of the attendees, especially Irene. For the first time, Rockwell felt like one of the family.

After the festivities, the family gathered at their summer camp a few miles away in Louisville Landing. Relaxing on the shoreline of the St. Lawrence River, conversations led to predictions about the future decade.

A spirited discussion followed, but soon Rockwell’s brother-in-law, Howard, and Irene’s father grew restless and invited Rockwell to walk with them. The three men eventually ended up at the town’s small dance hall, watching out-of-towners dance to the latest hits. As fascinating as the dancers were, several couples ringing the perimeter of the dance floor—sitting face-to-face, knee-to-knee and moving small heart-shaped objects (planchettes) on Ouija boards—were even more intriguing to Rockwell. Recalling their earlier conversation, the artist joked to Howard, “Maybe they can predict what the ’20s will bring.”

Nothing more was said about the matter, but six months later on February 3, 1920, Howard visited Rockwell in his New Rochelle studio to wish him happy birthday. Walking over to a couple of paintings resting on easels, he commented to Rockwell, “This looks like one of the couples using the Ouija board last summer.”

In fact, it was. The previous summer’s weekend celebration in Potsdam inspired the illustration “Ouija Board” featured on the May 1, 1920, cover of The Saturday Evening Post (above). Norman thought it was a trendy cover, perfect for the new decade, and used New York City models Betty Keough and Henry Von Bousen in the illustration.

Another canvas nearby featured a young couple looking at blueprints of a new house with a small child beside them. Howard asked, “Will this be the Rockwell family someday?”

“I don’t know,” the artist replied. “Do you have a Ouija board?”

Rockwell in the 1950s – Part II of III

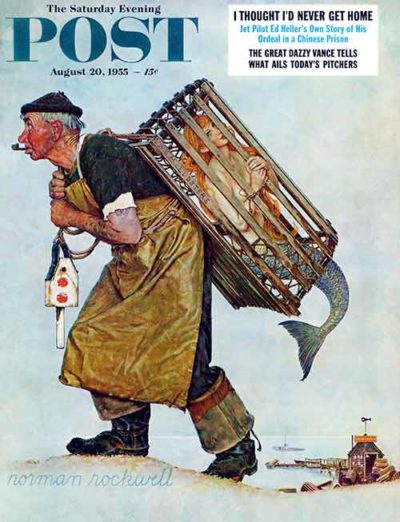

“Unexpected Catch”- August 20, 1955

"Unexpected Catch"

From August 20, 1955

Letters to the editor ran the gamut.

“…[Y]ou have reduced your magazine to one which any decent American would rather be without or hide because of the obscene picture on the cover.” Don’t laugh. I receive and distribute enough “Letters to the Editor” to know there would be very similar comments today. Of course, if this is “obscene,” centuries of great masters should be ashamed of themselves.

But an overwhelming number of 1955 readers were pleased. “What did you expect a mermaid to wear? A sweatshirt?” wrote a Michigan reader. A letter from Alabama asked, “What bait is best?”

The original painting is in the collection of Director Steven Spielberg, an avid Rockwell collector.

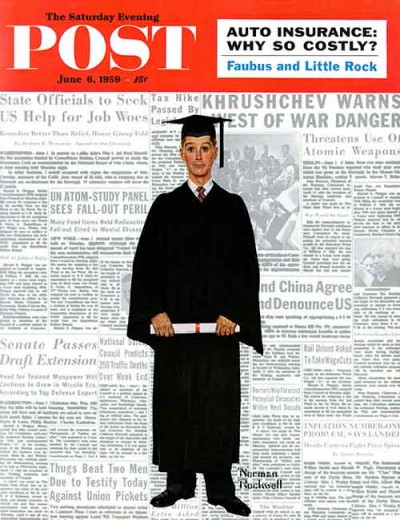

“The Graduate” – June 6, 1959

"The Graduate"

From June 6, 1959

It’s 1959 and the news is grim. Krushchev is threatening to use atomic weapons; inflation and job woes dominate the news, and, according to the old newspaper, thugs beat two men set to testify against union pickets. It’s an ugly world out there. Our young graduate looks appropriately wary as he sets off to solve all these problems.

As seen in the photo above, Rockwell created a life-sized painting of the soon-to-be-cover. Post editors couldn’t resist asking Norman if he ever fell from his stool while painting the graduate, making no attempt to squelch images of the artist face-down in his palette. Editors were like that because a) America’s favorite artist falling on his noggin would make a great story, and b) they just enjoyed giving Norman a hard time. To paint the lower portion, Rockwell came down and sat in his regular chair. Post editors had provided the background newspaper, saving the artist some detail work, so he claimed he was making sure the Post got its money’s worth in square feet. The great Norman Rockwell was not above dishing it back.

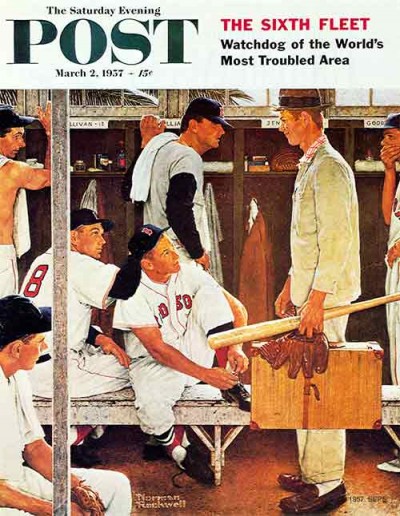

“The Rookie” – March 2, 1957

"The Rookie"

From March 2, 1957

Rockwell and baseball—what could be more American? In the 1957 Red Sox locker room, a rookie shows up at spring training (hint: this must be spring training, since the palm trees in the window clearly rule out Boston!). Playing the part of the rookie was local baseball star Sherman Stanford. Real Red Soxers filled out the scene: Lower left was Sammy White, and the other two players sitting were Frank Sullivan and Jackie Jenson. Behind the rookie, Billy Goodman is wiping away the smile. These gracious gents visited Rockwell to pose, meeting the neighbors while they were there, making the artist even more of a hero to the townsfolk.

The shirtless guy to the left was referred to by Rockwell as “John J. Anonymous,” who once tried out for the Red Sox. He was thrilled when “manager” Rockwell put him in the line-up. Ted Williams stands in the middle, which was a good trick, since he couldn’t make it to the studio. The artist used a stand-in and consulted his baseball card collection to get Williams’ profile. He always knew that bubble gum would come in handy.

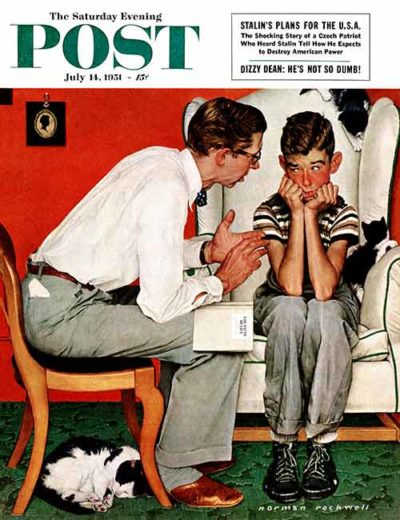

“The Facts of Life” – July 14, 1951

"The Facts of Life"

From July 14, 1951

Birds and bees are okay, and I understand about Fluffy and her kittens, but this other stuff is revolting.

Dad has to be given credit for attempting to explain that although mothers and fathers sometimes feel like throttling each other, they really are in love and children come along. Then they work hard to keep food on the table and the mortgage paid for those offspring who sometimes annoy and worry their parents to distraction. But all in all, brave Dad concludes, life is a pretty darn good invention.

Junior has his own conclusion: this is just Too Much Information.

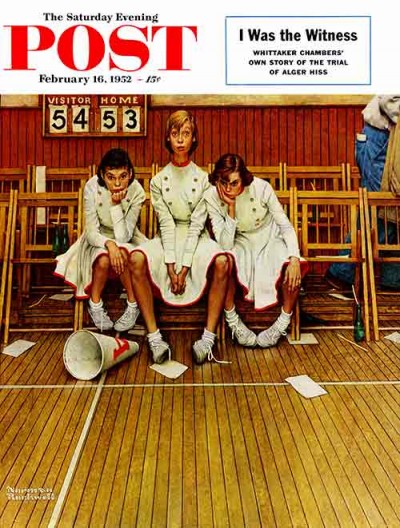

“Cheerless Cheerleaders” – February 16, 1952

"Cheerless Cheerleaders"

From February16, 1952

Wooden gym floors and cheering on the team—memories are made of this. But not all the memories are joyous. The other team got lucky with a last-second shot, leaving the middle girl in shock and her cohorts looking like dejected bookends. It is no consolation that this is the character-building aspect of sports.

But, girls, even older folks remember cheering their hearts out for the home team, and the feeling of the stomach plunging five stories as the boys’ brave efforts fall apart. So you are entitled to a good cry before remembering that you guys whipped them last season, and by golly, you can do it again next time!

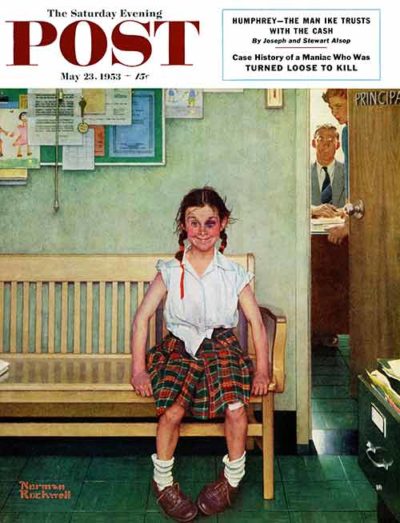

“Triumph in Defeat” – May 23, 1953

"Triumph in Defeat"

From May 23, 1953

Yes, that is Mary Whalen again. You saw her in the first segment of “Rockwell in the Fifties” as “The Girl in the Mirror” and in “A Day in the Life of a Girl.” But don’t worry, she didn’t really have a black eye—the toddler pictured below did.

Rockwell loved the idea of a smug schoolgirl who bested her opponent in a fight. This, of course, leads to the Principal’s office, where inside there is some discussion on just what to do with the miscreant.

Rockwell underestimated how difficult it was to paint a black eye. He tried smearing charcoal around Mary’s eye, but that didn’t work. A black eye is more complex, with a bit of yellow, a touch of purple, some red, and a certain puffiness. His attempts to create a shiner from memory were not working. He decided to find a kid with a real black eye he could duplicate. He called all his contacts, even local hospitals, but it seemed nobody had a kid with a fresh black eye in stock.

As we would say today, his plight “went viral.”

A Massachusetts photographer decided to run an ad requesting a child with a black eye and it was picked up by the wire services. Rockwell himself offered five dollars for a nice ripe one. Responses ran from a prison warden down South who wrote that there had been a riot and he had hundreds of black eyes available to a father who cracked he would give all of his kids black eyes for five bucks (that joke probably played better in 1953). Finally, a little boy named Tommy managed to acquire two black eyes, as active little kids sometimes do, and his father drove him from Massachusetts to Rockwell’s studio in Vermont. Even the little children must suffer for art, but at least little Tommy got his picture in the Post:

“The Cover Shiner” – May 23, 1953

Presenting Tommy Forsberg, his black eyes, and his dad.

"Perfect!"

cried Norman Rockwell.

Next week: Final installment of Rockwell in the 1950s.

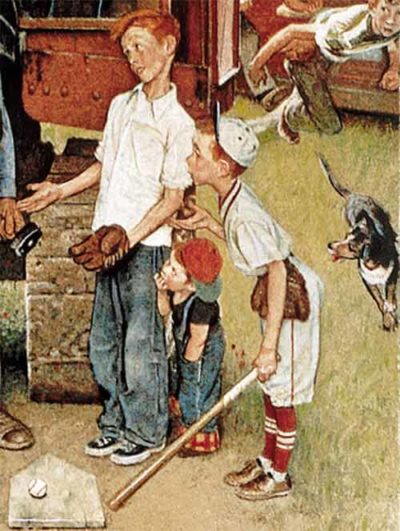

Rockwell in the 1950s – Part I of III

“Rockwell Models”

Rockwell Models in “Progress?”

From August 21, 1954

One advantage of living near Rockwell in the 1950s is that you had a good chance of being forever remembered in a Saturday Evening Post cover.

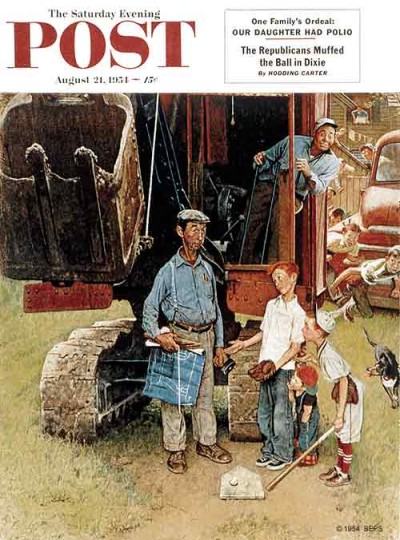

“Progress?” – August 21, 1954

“Progress?”

From August 21, 1954

This is progress? The construction crew is meant to build a cellar, but along come the local would-be All Stars pleading, “Gee, mister, this is our baseball lot!”

Rockwell gathered up models for this scene in midwinter by knocking on doors (in Stockbridge, Mass.) and rousting up members of the Little League team. My favorite touch is tiny Scott Ingram sucking his fingers as the negotiations proceed. The boy in the baseball suit is big brother, Kenneth Ingram. We’ll see Scott again.

The workers appear sympathetic, but we suspect things do not bode well for the great American pastime.

According to Kenneth, Scott’s best buddy was Eddie Locke (below).

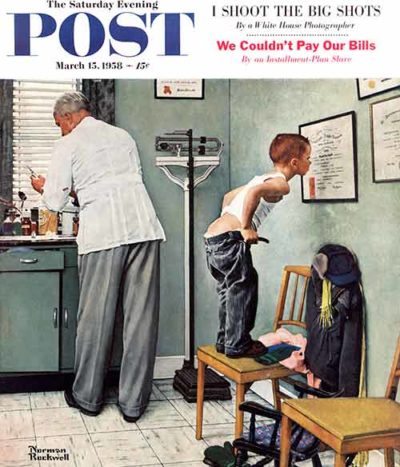

“Before the Shot”– March 15, 1958

“Before the Shot”

From March 15, 1958

We recently showed you Eddie Locke as “The Runaway” (see: ROCKWELL: BEHIND THE CANVAS). The young man shows up on yet another classic Rockwell cover: as the boy checking out the doctor’s credentials before getting a shot.

The physician preparing the shot was Donald Campbell, a real local doctor. “Norman lived across the street from me for a number of years, said Dr. Campbell in a 1976 issue of the Post. “It was a familiar sight to see his long legs carrying him down to the studio regularly before eight a.m. “

Dr. Campbell continued, “Norman couldn’t help being nice to people, especially children. When my five-year-old Betsy fell from her bike because a little dog followed her, barking, Norman gathered her up, stopped her tears and took her home with him. With Betsy on his knee, he drew a series of pictures as in a cartoon, showing a little dog chasing a little child on a bike. The picture showed the little girl’s face with the caption, ‘See. The nice little dog only wanted to play.’”

“Girl at the Mirror” – March 6, 1954

“Girl at the Mirror”

From March 6, 1954

Rockwell once called Mary Whalen his favorite model, even if the young girl on the cover didn’t think she measured up to Jane Russell (who did?). The artist captures the “in-between” age well between the cast away doll and the closer “necessities” of lipstick and hairbrush.

Mary’s first memory of the artist “was at a high school basketball game in Arlington, Vermont, about 1950. His son Tommy was on the local team, so along with nearly everybody else in town, Norman was there to cheer them on. When I harassed my Dad for a Coke, a friendly man sitting behind us gallantly reached over my shoulder and invited me to drink some of his Coke. That was the beginning of my admiration for Norman Rockwell.”

How did Rockwell get the facial expressions he wanted from the kids? “He would laugh and shout, pound the floor, or jump up and down,” Mary recalled. “He did the acting while I reacted. What a wonderful moment of joy when Norman drew forth from me the expressions he wanted. He would burst out laughing, with happy shouts. It is the memory of those triumphant, creative moments which I treasure most,” she recalled, more than twenty years later. “I can still hear deep within me his laugh of celebration.”

“A Day in the Life of a Girl” – August 30, 1952

“A Day in the Life of a Girl”

From August 30, 1952

Earlier in 1952, Rockwell did a cover called “A Day in the Life of a Boy,” which follows a boy getting up and ready for school, playing baseball, getting distracted by a pretty girl, and so on. A few months later, the summer version, “A Day in the life of a Girl” appeared. Both covers featured Charles Marsh, Jr. and Mary Whalen. Mary awakens, then it’s off to go swimming, where a young man promptly tries to drown her. The spirited lass returns the gesture, and it was love at first fight.

The last row shows a chaste kiss, which Marsh just couldn’t pull off. “I considered her my girlfriend then,” he said later, but I had never built up enough courage to kiss her. Mr. Rockwell finally gave up on trying to get me to kiss her and posed us puckering separately.” The ordeals of being a model!

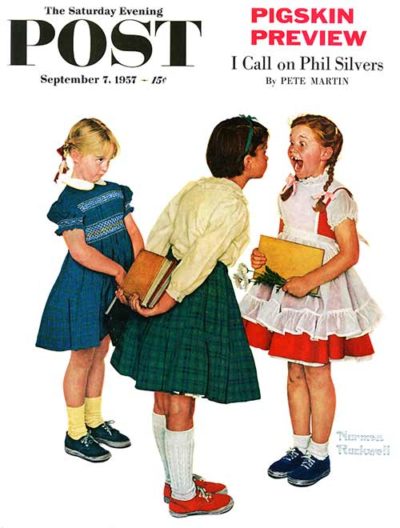

“The Missing Tooth”- September 7, 1957

“The Missing Tooth”

From September 7, 1957

When Rockwell needed a child for a Crest ad (“Look, Ma! No Cavities!”), he asked his friends, the Morgans, if he could borrow their daughter. When cute little Ann Morgan showed up at the studio, she was missing two front teeth. Oops. “Mr. Rockwell went ahead and painted my front teeth in for the ad,” said grown-up Ann Morgan Baker in 1976, “but my missing teeth may have given him the idea for a Post cover.”

Living near a famous artist had its perks: “Being on the cover changed my life,” Ann said, “People were always saying, ‘I saw you in Chicago,’ or ‘I saw you in a drugstore window in New York.’ I thought of myself as a tiny little international star.” And the modeling fee? “$25 when you’re six is a lot of money.” Famous AND rich—what more could you ask for?

Having Rockwell as a family friend has its odd moments, too. The artist would call Ann’s mother “at 7 a.m. and say, ‘Don’t make the beds. I want to come and look at some messy rooms.’ Then he would come and wander through our morning rubble.”

Ann’s first love? Neighbor and fellow Rockwell model, Scott Ingram (above as the littlest ball player and below).

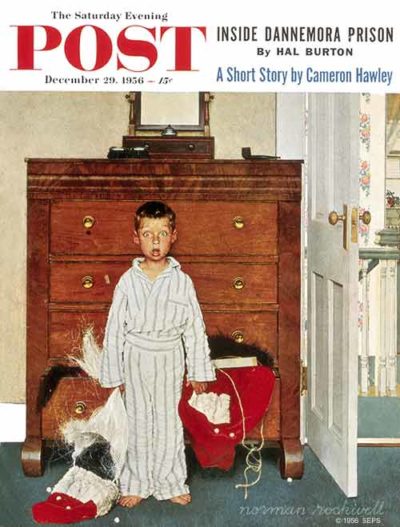

“The Discovery” – December 29, 1956

“The Discovery”

From December 29, 1956

Poor little Scott Ingram—this unexpected discovery is suddenly answering a lot of questions. The good news is that this 1956 cover also made him a celebrity of sorts. He actually got fan mail and even made a television appearance with the famous artist. He enjoyed working with Rockwell, and looked forward to the end of each session, when he would be treated to a milkshake.

The painting is more multi-faceted than the first glance would indicate. The way Rockwell captured the burling of the wood of the dresser is one such detail. And life for the artist would have been easier had he just closed the door. Instead, he replicated the patterned wallpaper outside the room, illuminated by the light of a window we have the barest glimpse of.

Next: Rockwell in the 1950s Part II —including a controversial topless model.