A Summons to England

Even in business class, with an empty seat beside her, Becca couldn’t sleep. She turned on the overhead light and read the conference materials, Tort Law in Transition, 1982-1992: A Transatlantic Perspective.

She hadn’t wanted to go to London. She knew she should be chuffed, as Liam would put it, being asked to stand in for a senior partner and speak about American class actions. It was March 1992; the partner’s typed notes rambled on about patients suing the manufacturer of faulty heart valves; female coal miners alleging harassment; Vietnam vets suing Dow Chemical for diseases from Agent Orange. Becca had little experience with class actions; she suspected she was asked because she spent her first six months assigned to the firm’s London office. A coveted gig, that one, too, even if in reality it was a glorified document review. It changed her life forever. While living there, she met Liam, at the London Apprentice Pub in Isleworth.

“Didn’t I hear you have an English husband?” the partner asked when he showed up in her office Friday afternoon. “He can go too, if you like. You’d only have to pay his airfare.”

Becca said her husband couldn’t miss work. The partner stared at the only picture on her wall — a Hogarth reproduction: a bewigged barrister on a throne, scrawny clerks scrivening below, scales of justice lurking in a corner. The partner was looking for a wedding picture or at least a photo of Becca and Liam engaged in some sport, standard décor for recently-married lawyers. But there was no photo of Liam, or of Becca either, only an empty space on the wall above her desk, where a picture-hook remained.

The partner didn’t know that Becca’s English husband had left her. None of the lawyers and staff with whom she worked knew. Nor did her mother, who had moved to Florida and barely knew Liam. Nor her best friend from law school, who lived in Chicago and worked crazy hours, like Becca.

Later than she should have, Becca realized Liam wasn’t coming back. After Liam had been gone two weeks, it was her birthday. She thought she’d hear from him. When Becca’s mother called from Florida, she was all excited about the play her drama club was doing, Moor Born, about the Brontes. She was playing Anne, the least famous, least creative sister; nonetheless, the competition had been fierce. “By the way,” she asked, “what did Liam get you for your birthday?”

“It’s a surprise,” Becca said. “For tonight.” Her mother asked her to report back. Becca knew she wouldn’t ask again unless Becca brought it up.

Nine months later, the opportunity to tell someone — anyone — was gone.

Liam left in June, at the end of his second year teaching science at Manhattan Prep in Yorkville. He said he needed time to himself after the intense push of proctoring, grading, and graduation. He’d gone off this way before, beginning when they lived in Isleworth. He always returned the next day, or the day after.

This time, days became weeks; weeks became months. She wondered if he had returned to London. His passport was missing. But if so, where would she begin to look for him? With his cousin Saul? The two didn’t get along. Becca and Saul were more simpatico than Liam and Saul had ever been. Their six months in London now seemed a dream, fleeting and unreal. Liam had introduced her to only one friend, a struggling actor named Trevor Thorn, who was heading to Australia to appear in an independent film. There were Aunt Lillian and Aunt Rachel, both around 80, older sisters of Liam’s father, who died of a heart attack at 65. Liam referred to his spinster aunts and his cousin Saul as “the Jewish side of the family”; stuck in the Old World, he said, even though born in Leeds. The aunts had lived together for decades in a small flat in North London. When Liam learned that Becca was Jewish, he said, “I have some people I’d like you to meet.” Soon afterwards, he took her to visit the aunts. It was as if his Jewish lineage, for once in his life, enhanced his standing.

Several times after that first visit she went to see the aunts on her own. During her time in London, they were exceptionally kind to her. Aunt Lillian, with her erect posture and stark white cap of hair, her take-charge voice, grasped Becca’s hands to welcome her to their flat. Aunt Rachel was softer, rounder, her gaze transparent and direct. She listened intently to Becca, nodding encouragement, as if she knew what Becca was going to say before she said it.

Then, on a Saturday when Liam was gone, Becca ran a fever. She tried to reach the London office manager, but couldn’t. Her heart and head pounded; the room spun. She phoned the aunts. Eventually a knock. Aunt Lillian directed the driver to a North London clinic, near the aunts’ flat. A nurse wheeled Becca into a room so white she had to close her eyes. Someone undressed her and put her in a hospital gown, hooked her up to an IV, although Becca had no memory of any of this.

Becca woke in the North London hospital and there they were: Lillian in a chair, Rachel fussing with a tray. The smell wasn’t the normal hospital smell. “The sweetness of the soup,” Aunt Rachel had explained one Friday evening, “is from parsnips. On Fridays the grocer saves some for me.” Rachel settled on the side of the bed and brought a spoon to Becca’s lips. “Warm,” she said. “Not scalding.” Becca didn’t know how long she’d been in hospital, how long the aunts had been there. She wondered where Liam was.

That time, he came home the next day.

One of the aunts had died in January. Liam’s cousin Saul had written to her about it. She and Saul corresponded a few times a year since she left England, even after she married Liam. They’d spoken on the phone, too, usually when she was in the office, working late. Sometimes they discussed their legal work (Saul was a solicitor, specializing in wills and estates) or items in the news. But the main subject was Saul’s involvement with the Jewish East End Society, which promoted the work of Isaac Rosenberg, a World War I poet. Becca majored in English in college and concentrated on early 20th century English poetry. Yet she had never heard of Isaac Rosenberg until that first afternoon in the aunts’ flat, when Saul showed up late, his voice breaking with excitement about the new installation devoted to World War I poets, including Rosenberg, in Poets’ Corner in Westminster Abbey. “This is rather childish,” Saul said that day, “but I got interested in Isaac Rosenberg because of his last name, same as ours.” He included the aunts and his cousin Liam in the sweep of his hand. “Turns out we’re not related.”

“My last name isn’t Rosenberg,” Liam interjected. His father had shortened it soon after Liam was born, erasing all evidence of his Jewishness. “From my research,” Liam joked, “Rose is a good Scottish-Irish name, dating back to 1273 and Thomas, son of Rose, of Cambridgeshire.”

The day before the flight to London, Becca called Saul from her office in Manhattan. She dialed his work number, expecting an answering machine. She would leave a message that she was coming for a conference. That was all. She didn’t know if Saul would want to see her, or what she would say if he did.

To her surprise, he answered. “Funny you should call. I was over on Finchley Road and came here to clear up some things. We were speaking about you. My aunt’s taking it hard. Her little sister’s death. I told her I had let you know. She was wondering.”

“I’m so sorry. I should have written.”

Saul said he would pick her up from the airport. She protested that she could take a taxi and get reimbursed. Rush hour traffic was horrendous, he said; he could navigate the arteries of London better than most.

She gave him her flight number.

“I’ll be there,” he said, and for a moment her heart lifted.

On Sunday, she went to the office of the Jewish National Fund to plant a tree in memory of Aunt Rachel. “It’s not simply planting memorial trees anymore. We have other options,” the woman said, hair in a bun, tendrils escaping, glasses on a chain around her neck. On the wall were samples of different certificates and before-and-after photographs of bare deserts transformed into woodlands; the blueprint for a water reclamation project. “Here’s one that might interest you. The certificate recites a line from Isaiah, I will make of the wilderness a pool of water. The donation will support a JNF-sponsored water project.”

Becca explained that the donation was in memory of an elderly Jewish woman who lived in London, and that the certificate would go to the woman’s sister. The JNF lady considered that information. “Of course, there are always the trees. The British love to plant trees in the Negev, whatever the occasion.”

At Becca’s office, the mailroom clerk told her she was in luck; normally the pouch didn’t go out Sunday nights, but there was a bond offering on Tuesday and some notarized documents were going by courier to the firm’s London office for Monday morning delivery. They would deliver her envelope to Finchley Road on Monday morning, too. She wrote a condolence note on the firm stationery, which she inserted in the envelope with the certificate. Dear Aunt Lillian: I was so sorry to learn from Saul of Aunt Rachel’s passing. I know how close the two of you were. I will never forget the kindness both of you showed Liam and me when we came to your flat. On the holidays, you made me feel like a member of the family. I’ve made a donation to the Jewish National Fund in Aunt Rachel’s memory — the certificate is enclosed. Love, Becca

She brought her envelope to the mailroom and put it in the London pouch, with instructions to deliver it Monday morning. She wanted her condolence note and the JNF certificate to arrive before she did, to make up for not acknowledging Aunt Rachel’s death earlier.

On the plane, she read the conference materials, which covered new developments in England and America; insurance; cases against public authorities; and mass torts. For the last day, they highlighted a provocative panel on Tort Law as a System of Personal Responsibility, which posed several questions. Shouldn’t a rational person protect against mishaps or injury when planning a future action? Isn’t the failure to do so responsible for any misery that ensues?

She thought then of Liam, the source of her misery. She had done nothing to protect herself.

The evening meal service began. Becca said, no, nothing for her, but the cabin was cold and the flight attendant urged her to have the soup, chicken broth with noodles. A surprisingly tasty soup, it made Becca think of the soup Aunt Rachel brought her all those years ago, when Becca was stricken with pneumonia and too weak to eat. Aunt Rachel spoon-fed Becca, her grey head bent over the task; Aunt Lillian urging her not to spill.

Becca took Saul’s letter from her briefcase. Reliable Saul, who would be there to meet her. She felt warmed by that as much as by the soup. “I’m sorry to have to tell you that Aunt Lillian has died. No one expected it and as you can imagine, Aunt Rachel is beside herself with grief.”

She read it again.

Surely that wasn’t right. Surely Saul was mistaken.

By her third reading she knew she had made the donation and had JNF print the certificate in memory of the wrong aunt. Aunt Lillian had died, not Aunt Rachel. The packet being hand-delivered by the firm’s London office was addressed to Lillian but Aunt Rachel would be the one to receive it at the Finchley Road flat. She would open it eagerly, longingly, wondering what it could be.

The first time she met the aunts, she and Liam were invited to Finchley Road for tea. She expected Earl Grey and biscuits; instead, there was sherry, followed by pistachio-encrusted plaice, crisp roast potatoes, fresh peas, and strawberries with condensed milk. Aunt Lillian led the conversation, questioning Becca about her work, her family, how she and Liam met. Becca described her walk from Richmond to Isleworth. She was tired, hungry, and thirsty, and there it was, overlooking the river, The London Apprentice, with swans from central casting. And Liam.

Eventually, the only sound in the aunts’ flat was spoons scraping plates. Becca said she would do the washing up; both aunts protested mildly, but a fleeting look passed between them. Liam, who lounged at the table, his long legs extended, his chair tipped back precariously, made no move to get up. She assumed his aunts wished to speak to him alone.

In the kitchen, over the sound of water running in the sink, Becca heard raised voices: Lillian’s: “sleeping with others” and “Sarita and Ned” and “he’s your son.” Liam’s “I told her.”

What had he told her? Was the her in question Becca?

Liam had told her he had a son from a prior marriage. His ex-wife didn’t permit him to see the boy much. When the boy was older, presumably that would change. “For now,” Liam said, “there’s not much I can do.”

The first time Liam disappeared from Isleworth for two nights, after his return Becca asked him whether he had seen Ned. “I’d rather not talk about it,” he said. She didn’t ask him again.

On New Year’s Eve, 1987, Becca was alone in the Isleworth flat when the aunts called. “Where’s Leo?” Lillian asked. “Isn’t he with you?”

“You mean Liam.”

“Well, he calls himself that now. But he was born Leo, and he’ll always be Leo to me. Where is he?”

Becca said New Year’s Eve was a rare time when Liam’s ex-wife allowed him to spend the evening with Ned, who was 15. He’d stay overnight in Sussex.

“Is that what he told you?” Aunt Lillian asked.

She must have dozed, because she woke suddenly when the lights in the cabin came on. Damp croissants, English butter, and tea were served. The conference materials were still in the seat pocket, open to the page about the theory of personal responsibility in tort law. Often the victim is in the best position to consider the potential harm that might befall her.

At Heathrow, as promised, Saul was waiting. He greeted her with a bear hug, with his warm brown eyes, with obvious pleasure. His beard was trimmer than she remembered; his curly hair neat and trim, too.

Surely the envelope addressed to Aunt Lillian had arrived, and Aunt Rachel had opened it. But plainly she hadn’t spoken to Saul yet. Saul was chatty and light-hearted in the car; Becca, anxious and wary.

She hadn’t wept on the flight but felt like weeping now. She hadn’t been hugged like that in a while. The damp mist of the London air held her in check, like the cold water she splashed on her face in the plane’s lavatory.

“Are you nervous?” Saul asked. She looked at him blankly. “About your speech? It’s an honor, isn’t it? To represent your firm. But probably nerve-racking too.”

Saul was right. She should be worrying about her talk, rehearsing it, anticipating the questions. Instead she was consumed with being back in England, without Liam; consumed with her mistake.

According to the conference materials, she couldn’t register at the hotel until 3 p.m.

Saul was delighted. “There’s a Rosenberg exhibit at the Imperial War Museum. We can go before you get busy.”

He had taken the day off to be with Becca. “Yesterday I told Aunt Rachel you were coming. She insists we come for tea this afternoon. It’s the most cheerful she’s been since Aunt Lillian died. You know Aunt Rachel. She’ll serve us something.”

At the museum, Becca tried not to think of Aunt Rachel’s inevitable distress. Rosenberg was a painter as well as a poet. In the trenches, he turned exclusively to poetry. He wrote from the view of the lowly infantryman about the lice that tormented them, the shrieking near-dead, the rats that traversed the no-man’s land between Englishman and German. The men shipping out:

Grotesque and queerly huddled

We lie all sorts of ways

And cannot sleep.

Becca read and reread his earliest war poem, written before he enlisted:

Three lives hath one life

Iron, honey, gold.

The gold, the honey gone

Left is the hard and cold.

Honey was love; gold was work. That much she knew. Iron was war, hard and cold. Becca stood before a photograph of Isaac in an ill-fitting suit, the jacket buttoned tight across his chest; his younger brother Elkon in army uniform, his arm flung around Isaac’s shoulders. Both Isaac’s brothers fought in the war too. Their mother’s calmest moments came when her boys were in army hospitals. But the hospitalizations didn’t last long enough – or at least not long enough to save Isaac.

“I love that photo,” Saul said. “The suit Isaac is wearing was the family suit. He and his two brothers shared it. But look how he and Elkon are smiling.” The photo was taken in September 1917. Isaac’s last leave.

Becca imagined how Isaac’s mother felt when she learned her eldest son had been blown to bits on French soil. His remains were never identified. He and the other members of his company who went out that morning were buried in a cemetery in Nord-Pas-de-Calais, the authorities unable to separate the remains of one soldier from another.

All disappearances are not equal, Becca thought. How poorly she had dealt with Liam’s disappearance. How cavalier she had been about an aunt’s death – as Liam himself would have been. Had she simply thought, absently, one of them died, as if which one it was didn’t bear noting? She couldn’t remember.

By what pale light or moon-pale shore

Drifts my soul in lonely flight?

Rosenberg was 23 when he wrote that; not quite 28 when he died.

“Look at this.” Saul drew her to an oil painting, “Head of a Woman ‘Grey and Red,’” from 1912. “Quick — who does she remind you of?” Becca didn’t know. “Isn’t she like a younger version of Rachel? The soft mouth, the clear blue-grey eyes, paying attention, always paying attention, and the hair pulled back the same way.”

“She’s pretty,” Becca said.

“Aunt Rachel is too, isn’t she?”

Becca had never thought so. She hadn’t thought Rachel wasn’t pretty either. But then, she had never really looked.

Saul deftly navigated the side streets on the way to Aunt Rachel’s, turning to avoid the traffic jam near Hyde Park. That’s when she saw him, or thought she saw him. Liam. A tall man with flowing blonde hair, shoulders hunched, a grey tweed overcoat, walking fast. She used to tease Liam about that coat. “All you need is a pipe,” she’d said. “And a Deerstalker.”

“The hat, never. The pipe, who knows?”

The tweed coat was gone from the closet in New York. When Liam left he knew it wasn’t for a summer weekend. He knew. She followed the figure as long as she could. He had Liam’s limber gait and long strides. But traffic was stopped, with only occasional lurches forward and she lost him. Her stomach lurched too, with hunger, with loss, with the debacle to come.

Saul hadn’t noticed the man she thought might be Liam. “The other night when you called,” he said, “I thought it was to resume our midnight talks. We hadn’t had one for a while. It wasn’t midnight in New York of course. But I figured that was the reason.”

Becca was half-listening, wondering whether the man she saw was Liam. For a moment, she had no idea what Saul was talking about. Had she actually engaged in midnight conversations with Saul?

Of course. One night three years ago, long after she and Liam were married and living in New York, she was in the office at 11:30 on a Saturday night, working on an emergency motion. Liam was off somewhere. Part of her wanted him to return and find her gone, wanted him to wonder where’s Becca? The phone rang. She let it ring, but picked it up before it went into voicemail. Suppose the partner was looking for her draft? “This is Becca.”

First, silence; then, Saul’s voice. “I didn’t expect to find you. Just woke up. Can you hear the birds?” He paused, then continued, not quite coherent. “Our last conversation, the war poets. A new book. Going to leave a message.” His voice husky, the barely awake morning voice of a man before he turns to you, filled with desire. It was 5 a.m. in London. “I know attorneys work late in New York. But midnight on Saturday?”

And so their midnight conversations began. They continued sporadically after that, always when she worked late. Sometimes she initiated them; sometimes Saul did. Often they made her feel unsteady. A discussion of Isaac Rosenberg’s portrayal of Adam and Eve — a painting, not a poem — disturbed her dreams. Then there were lines from an unfinished verse play that Saul particularly liked: Aghast and naked, I am flung in the abyss of days. After Liam’s disappearance, abyss of days seemed a familiar, even comforting, way to think of her existence.

Once she and Liam had skipped up the steps of the red-brick Victorian. The building had white pillars and an old-world air even though it had been converted to flats. Liam had kissed her on the landing. Now four years later she climbed the same steps, trailing behind Saul. The flat was in the back on the first floor; a slim dark mezuzah of burnished metal to the right of the door. Saul rapped lightly.

“It’s open,” Aunt Rachel called. She sat on the dark green velvet sofa. Three places were set around an oval dining table, the soup bowls in a quaint country pattern, rose and white. The apartment smelled of chicken soup.

Aunt Rachel wore a long-sleeved dress — a soft blue-grey color — with pearl buttons. Her eyes were the same color, the color of the girl’s eyes in Rosenberg’s painting.

Becca spotted her envelope on the end table near the sofa. She saw the JNF certificate and her condolence note on the floor beside it. She saw the certificate’s artistic depiction of a tree, its sheltering branches, designed to provide comfort after a death.

Only Aunt Rachel hadn’t died. Her sister Lillian had. Becca expected Rachel to be angry or bereft or weepy. She expected her to tell her devoted nephew Saul about the carelessness or cruelty Becca had perpetrated. Saul wouldn’t find Becca’s mistake funny.

In fact, it was the kind of thing Liam might have done. A failure to pay attention, a feckless act bordering on malice.

“Becca!” Aunt Rachel said. “Welcome! How was your flight?” She stood up, grasped Becca’s hands. Becca replied that it hadn’t been bad. Her first time in business class, paid for by her firm.

“Aunt Rachel!” Saul said. “Don’t I get a kiss?”

“Certainly. But first I want to look at Becca. How are you? And how’s Liam?”

“Working as we speak. We both work a lot. Sometimes we barely see each other.” Her voice sounded plaintive, self-pitying, not what she intended. The lie was not what she intended either. She thought she could dodge questions about Liam. But instead she had lied.

“How does he like New York? Do you miss your little flat in Isleworth?”

Saul intervened. “You lived opposite The London Apprentice, didn’t you? If you have a free afternoon, the three of us could drive there for lunch. It’s a lovely spot.”

Becca wasn’t sure she’d be able to leave the conference at lunchtime. “It is a nice pub, isn’t it?” she said, glad to change the subject. The day she met Liam she’d been so pleased to find it, a beautiful location on the Thames, mentioned in her guidebook. She was tired and a bit lonely. A shadow, the late afternoon sun in her eyes. She looked up from her bread and cheese, her shandy. He asked if she came often to The London Apprentice. She said it was her first time. Did she know about the secret tunnel used by smugglers? “What did they smuggle?” she asked, meeting his eyes.

“Booty. Isn’t that what they call it? Mostly booze, I think. To avoid customs duties. After William Pitt abolished the duties in the 1780s, the smugglers lost ground. Proof that laws create crimes, not the other way around.” He was casually erudite as well as handsome.

Later, after they moved in together, she told Liam he didn’t need to tell her where he was going. The worst thing would be forcing someone to lie. For whatever reason. Even if what you were lying about didn’t mean a thing.

“Speaking of lunch at the pub, let me go warm up the soup. With parsnips. Becca’s favorite.” Aunt Rachel stood up with effort, more unsteady on her feet than Becca remembered. Becca saw how Aunt Lillian’s death had affected Rachel, reminding her perhaps of her own fragility, her mortality, her need to take care.

With Becca’s note and the JNF certificate to make things worse.

“You sit down and I’ll warm up the soup,” said Becca.

“But you must be exhausted from the flight. You shouldn’t have to do anything. You just arrived.”

Saul explained that they went directly from the airport to the Isaac Rosenberg exhibit, how Becca couldn’t check in at her hotel until 3 p.m.

“All the more reason Becca must be exhausted.”

“Ladies, I’ll take care of the soup.”

“A very low flame,” Rachel said.

Saul left them alone together. Instead of sitting back on the sofa, Rachel, without looking at Becca, gathered up Becca’s note and the JNF certificate. She brushed off some invisible dust and placed the items face down on some oversized books lying horizontally on a bookshelf.

She sat at the head of the dining table, summoned Becca to sit beside her.

Now was the time to apologize. But how to begin?

Rachel looked at Becca with the direct glance of the woman in Rosenberg’s painting. “Tell me really. How are things with Liam?”

It was as if she knew. Saul emerged from the kitchen carrying a covered soup tureen and a ladle.

“Saul, dear, there’s bread and a knife on the counter.”

Becca breathed in the sweet smell of the soup. She wanted to be quiet now, to sit and eat, but couldn’t. “Liam left me. Perhaps you knew?” Becca spoke rapidly, hoping to finish before Saul returned, but there he was with the bread, looking at her fondly.

“What did you say?” he asked.

“Nine months ago. It was mid-June, end of term. He said he needed a break. But he didn’t come back, didn’t call. A week later,” she struggled, “a week later, a letter arrived from the school, confirming that Liam had declined to accept the contract for another year. It said that if he ever changed his mind and returned to New York, they would welcome him.”

There was no retreat, no graceful way out. Were they angry she had lied? That she didn’t let them know earlier? “You’re the first people I’ve told. Not even my mother, or my friends.”

“How could you stand it?” Saul asked softly. “Alone?”

She quoted Rosenberg’s lines to him, the ones he loved. “It was an abyss of days. I got through by working. I thought of telling you, Saul. I wondered if he had returned to England. Perhaps he missed his son, or didn’t like New York. Or me.”

“That couldn’t happen,” Saul said. He looked away, picked up an apple from a bowl in the center of the table.

“I remember how after the two of you met, when you were living in Isleworth, Liam disappeared sometimes,” said Aunt Rachel. “Aunt Lillian and I worried about it.”

“I know you did. The two of you would ask, how’s our wayward nephew Liam? And Becca, how are you doing? You tried to warn me.”

“We didn’t know what to think. We thought he loved you, as much as he could love anyone. But maybe it wasn’t enough.”

“I realize something,” Becca said to Aunt Rachel and to Saul. Saul of the midnight phone calls, Saul who was managing to eat an apple quietly — not an easy task. “I thought love was one thing, and now it seems to be something else. What I thought it was, was the absence of lies. That’s odd, isn’t it?”

All three of them were silent after that. Saul looked for a place to throw out his apple core. “Here,” said Becca. She took the core and went into the kitchen, tossed it in the compost, wiped her eyes on a dishtowel. When she came back, no one said a word.

“Thank you for waiting,” she said.

They sipped the soup and ate the bread. “This is as delicious as I remember, Aunt Rachel. And it’s reviving me, too. Like it did when you brought it to the hospital.”

“You remember that?” Aunt Rachel looked pleased. She took another sip of soup and put down her spoon. “You both practice law. How long does someone have to be missing before you can dissolve a marriage, or declare them dead?”

Saul nearly choked on his soup.

Becca murmured that she didn’t know.

Someone would have to look it up.

Featured image: Shutterstock, by rumruay and Sergey Lavrentev

Not Margaret

She was sitting up when I got into her room in the hospital and she turned to look at me, surprised to see someone, and I walked up to her bed and it wasn’t her. It took a minute for me to realize it. She looked like herself, her face and her body in the bed, except for her expression when she saw me. It wasn’t the way she always looked at me. She looked at me and she smiled, politely. That was the first moment of something impossible.

I had stepped right up to her bed and gripped her hands in mine before I stopped to wonder at that odd smile. My voice came out thin and wavering, startled when I expected to be glad. “Margaret?”

She looked at me, serious and sad at once, and said, “What? No. No.” After a pause, she added, “Where am I? What happened? Who are you?”

Amnesia, I thought, it had to be. She couldn’t remember anything, couldn’t remember a thing, couldn’t remember me. That happens when people hit their heads. I’ve read about it, and seen a movie about a character who forgot his life and had to get it back. Sometimes they end up remembering, as they heal. I thought, I hoped, that Margaret had just left her mind for the time being and she was lurking in the crevices of her wounded brain, waiting to come back and recognize me. It didn’t occur to me that something else might have happened in her head, that somebody else might be there.

I gripped her hands tighter and I said, “It’s me, sweetheart. You don’t recognize me? You don’t remember? You had a bad accident but you’re okay. You’re going to be fine.” I think I went on for a minute or two longer trying to be reassuring, listening to the tremor in my own voice and the rasp of her breath against the stifling air.

She shook her head when my words trickled to a stop, and she winced with the movement. She said, “I’m sorry.” Her face was so calm when she looked at me, and that’s when I started thinking that something was so different that I didn’t recognize what was happening at all. I kept my fingers wrapped around hers. Margaret wasn’t calm. She snapped and sniped at every little thing. She complained about the people at work or my messiness, and her words were sharp. They made me laugh until she laughed too, reluctantly, but we always ended up either bickering or laughing. She was never calm or still like this.

She didn’t apologize, not even when she’d done something wrong. When she ate my leftover Chinese food or forgot to pay the electricity bill, the most I ever got out of her was a shrug. She didn’t say sorry and she didn’t expect me to. This version of Margaret was apologizing even though she was the one hit and pummeled and sleeping in a hospital bed alone for too long a time. There were lines pressed into her forehead — she looked worried about me.

My mind was racing, weaving over and under this thing that had happened until it was all wrapped up in confusion and fear. I kissed her on the forehead, like a child, before I turned away. I left the hospital that night just like I had the first night after the crash, with the collision still shattering my thoughts and anxiety in little sparkling shards that dug into me all night. The train ride back was painfully long and slow, like the train ride there had been. Then, though, I’d been so eager to see my Margaret, to see her eyes open. On the way home I kept seeing her face in my mind, in its innocent unknowing. I’d expected a gasp of relief and the electricity of excitement.

The next day, luckily, was Saturday. I woke up and went straight to the hospital, so hurried I forgot to brush my teeth and cursed my sour breath the whole way over. Margaret was sitting up, smiling at the nurse who was taking away breakfast. She turned her head, cringing a little, to smile at me just as she had done the day before. It was so strange that I stopped there, in the pastel doorway, and looked at this lover I didn’t know at all.

When I walked up to her, she seemed pleased to see me again. Her whole face was happy, her eyes bright. I’d never seen her look quite like that. I said, “Margaret,” in a kind of curious croak. She shook her head again, gentle this time, and her smile turned rueful. I said,

“Who then?”

She sighed, and there I saw a trace of my Margaret. That rhythm of breath was familiar to me. The inhale stretched the delicate lines of her throat and closed her eyes. The exhale seemed to take all the air from her body, and she had to gulp in more. When she sighed I felt my own chest burn as though my air were gone too. The cadence of her sigh was the same, and that linked my old Margaret to this new and strange one. Then she spoke and I noticed, for the first time, that her voice had changed. There was a new lilt to it. She said, “I don’t know. I’m not sure. I don’t know you, though, and I don’t know this place. The last thing I remember is going somewhere, to the market I think, with my brothers. I don’t understand what’s happening, and why my hands are so pale and my voice so high. I sound like a stranger to my ears.”

She sounded like a stranger to me too. Margaret didn’t have a brother, and this was not her voice, these were not her words. This woman pulled on her words in a way that my Margaret never did. She talked like somebody I’d never met. She was quiet, and careful with her speech, and she was terribly frightened. I sat by her bed, holding my hand over hers, and didn’t know what to say.

An hour later I said goodbye, and her face fell. There were familiar lines between her eyebrows, ones I recognized, snaking their way into her skin with worry. I clasped her hand, pressed too hard on her fingers, and I left. There was too much confusion gathered in my mind, a great spiky jumble of uncertainty that pricked and pulled at me the whole way home, and for most of the night too. The question that came to me, after a long while of tossing and turning and trying to get away from the anxiety that clung, seemed so obvious I was surprised at myself that it hadn’t occurred to me sooner. There was somebody else in Margaret. Presumably something like the crash had happened to this strange person from far away, with her voice that rose and fell like that. If she was here, in Margaret’s broken body, then where was Margaret?

The next night my anxiety wore all the way through me. My words bit at her with an edge I didn’t mean to put in them. “I don’t even know who you are, and I want my Margaret back. Why are you here? Who are you? God,” I said, standing and pacing, “I don’t even know if she’s still alive or anything. God.”

The fear came back to not-Margaret, her eyes wide and staring at me, but there was pity in them too. I think that’s what broke my heart a bit. That pity cracked me open. It’s the strangest thing that has ever happened to me, sitting at the bedside of the person I loved and missing her with a deep unending ache. I sat looking at her face and wishing she were there, watching some stranger look at me with pity through my lover’s eyes. Everything felt heavy then, and I thought my Margaret might just be gone. I put my head down on the squeaky mattress, closing my eyes against the glare and the linoleum. After a bit, not-Margaret traced timid fingers through my hair.

I stayed like that, feeling the warmth of her hand on my skull, until visiting hours were over.

Those quiet visits must have lasted for more than a week. I came and held not-Margaret’s hand and we looked at each other, lost in ourselves. Sometimes I played a song for her if it was stuck in my head, or brought her the paper or maybe a book. A couple of days I sat by her bed and flipped through the book I was reading or a newspaper, nudging her every once in a while to read something out loud. She would tell me which phrases struck her, and her voice would halt on some syllables as though words were unfamiliar. For that first week or so, we spoke in words that weren’t our own, and the words belonging to us stayed pushed down and silent. Then we had a true conversation.

She said, “Tell me a story about Margaret.” Her own name from her mouth, in her strange voice, hung like ice in my chest.

I drew in a breath and said, “Okay, let’s see. So Margaret’s best friend is named Jenny. She actually was a friend of mine in college, we almost dated for about two seconds, but we didn’t and then when I got together with Margaret I introduced them, and of course Margaret stole her completely.” Talking about her while looking at her face as if she were not there felt like something that happened in the dreams that slip into early mornings, half-dozing before you wake and realize that it makes no sense at all.

“We sometimes had Jenny over in the mornings on weekends, for breakfast. Margaret used to have breakfast with her mom, you know, after her dad died. I guess you don’t know, actually. Anyway, her dad died when she was 12 and her mom’s the distant type. They made French toast on Sundays though and they had kind of a ritual about it. So Jenny sometimes comes over and the three of us make French toast. I think Sundays are one of the few times Margaret is really content, peaceful, you know? She sort of lives in a state of perpetual stress but when Jenny is there it’s easier. She said, sometimes, that she was making her favorite meal with her favorite people.”

My throat hurt, talking about Margaret. I missed her, and missed seeing the way she shook when she laughed, as though she was trying to hold the mirth in and it burst out of her anyway. Jenny made Margaret laugh more than anybody else. I swallowed past the ache and kept talking.

“She and Jenny would play pranks on me, or make very complicated jokes that I didn’t get, or something. This one time they both, I guess, decided beforehand, and when Jenny came over they spoke French for the entire time. So they spent literally three hours, making breakfast and talking in French over my head and cracking up because they were being ridiculous and making up words and probably making fun of me while I understood about every tenth word they were saying.”

Not-Margaret laughed, and her laugh was not Margaret’s. It was lovely, though, one of those trills of sound that makes a person want to smile. It made me ache, deep and dull in my chest, for the unfamiliar beauty coming out of the person I loved.

I couldn’t pull out any more words, but not-Margaret saved me. She told me a little bit about her brothers, both older. She said, “They make me laugh the most, though they only let themselves joke about half the time with me. They could never make up their minds whether they wanted to tower over me and be scary or whether they wanted to be a big wall in front, making sure nobody else could get through to hurt me.”

“I know what you mean,” I said. “I have a little sister and I switch between being annoyed and being protective, that’s just part of being siblings.”

Her mouth twisted then, half-amused and half-wistful. “Either way, they were always around me. I always felt small beside them, threatened or safe, I was always small. Even now my brothers — ” She stopped talking, her breath whisked away.

She set her jaw and blinked hard, like a child trying not to cry. “They’re still protective and scary. We were going to the market, I think, walking along and they’re still trying to keep me out of the road. There weren’t any cars the way we were going, I was dancing all around and they’re torn between laughing at me and yelling at me, trying to get me to walk in a straight line out of the way.”

We looked at each other then, and the silence stretched between us. Her eyes were steady on mine, and finally she spoke. “I guess it’s a good thing I’m here.”

“What do you mean?”

“Well,” she said, “I mean, not that I’m in someone else, somewhere strange. You know that’s not what I mean. But if I had to be changed like this, however long it goes on, I guess it could be worse, right?”

“I guess,” I said. “Anyway. I should probably get going sometime soon.”

She shook her head, mouth tightening. “No, don’t. It’s early yet. Stay and talk to me a little while longer. Please.”

I stayed, her hand warm in mine and her voice lilting and laughing at me, until visiting hours ended and the nurse came around to kick me out.

Every once in a while, I forgot that she had been Margaret. The person looking at me from her eyes wasn’t Margaret. It got easier to think of them as her eyes, not Margaret’s eyes. They were the same color, they didn’t change, but they stopped looking like Margaret. They didn’t have Margaret’s glint of mischief, they just looked at me plainly. After a time, I looked at her without really seeing Margaret at all. I just saw her, for all that her eyes were a familiar shade of hazel and her face was written in lines I’d memorized over and over, shadows whose shapes were pressed in my mind in all their shifting patterns.

We got comfortable around each other. I stopped talking about Margaret, comparing them. It felt like we talked for ages. I visited every night, mostly until I had to leave, and it was a lot of nights. There was some complication with blood clots or something, and then they worried about something else. A bundle of health problems appeared. They all spread over Margaret like ink on a wet page from that one car crash that had blotted out her mind, staining her with somebody else’s bright colors. She stayed in that hospital bed another week, then another. It felt like a long time.

Once I walked into the hospital room to find Jenny sitting beside Margaret’s bed. They were talking quietly, and Jenny started when she saw me. She let go of Margaret’s hand and stumbled over her words for a minute, and then got out, “Good to see you, Margaret. I hope you feel better. I’ll just leave you two alone then.” She put her hand on my shoulder and left it there for a moment before she left. I wondered if I was imagining the hesitation that trembled on her fingers before she retreated and fled the hospital.

I sat by not-Margaret and asked her what they had talked about. She answered me, “Not so much, really. She asked me many times how I was feeling, how things were going, that sort. She talked a bit about her husband, her job, other friends I think. I told her many times that I was all right but still shaken, and that you’ve been wonderful and have visited me near every day.

“She looked a little confused at that, would Margaret not have said it?”

I shook my head. “I doubt it matters anyway in a situation like this, you can’t predict how people would act. Right? But you don’t think she could tell?”

Not-Margaret’s lips curled. I could see the laugh she was holding in her throat. “To tell the truth, I think she mostly talked so much she barely heard me. You were right, she is funny. And I tried to act tired, nothing else. Also, a nurse came by and said that they only needed to keep me here one, maybe two more nights.”

I sucked in my breath and sat quiet for a minute. Neither of us knew what would happen if — when — Margaret was released from the hospital. Not-Margaret had never been to our cramped apartment. She’d never sat swinging her legs from atop the tiny kitchen counter, or lain in our bed buried under the pillows and blankets overflowing to the floor. I think we were both afraid of what would happen then. There wasn’t anyplace else to go.

“Okay,” I said finally, letting my breath rush out in a gust. “I guess then we’ll go home.”

We looked at each other, wondering what that meant.

On Friday afternoon I took not-Margaret home, back to the apartment I’d shared with Margaret. I held her hand as we got on the train and she leaned against me. We jounced and jostled in the hard plastic seats and the curve of her forehead bumped closer into the crook of my neck with each toss of the train. It should have been familiar, but it sent tension arching in my bones and curling my fingers. When the train slowed at the first stop, I shifted a bit to put my arm around her. She started to withdraw as I moved, but settled back against me. The slap of footsteps and murmur of voices registered blurrily, at the edges of my mind. For that twenty-minute train ride, for every jerk and rattle that shivered us together and apart again, it seemed that my whole being was concentrated in my arm braced around her and her warmth nestled against the indent of my shoulder.

When the name of our stop crackled from the speakers, I stirred, and nodded at not-Margaret. She nodded back, her face pale and her lips pinched. I should have told her which stop we were.

Everything looked different now that she was here. The kitchen was small and dim, the sofa was nubby, and our bedroom was a hasty mess of sheets and laundry. The sun was sneaking away and left dingy light scattered across the floor. Not-Margaret wandered the apartment. She sat on the nubby sofa, and opened the drawers and cabinets. I cooked. She sat on the bed, cross-legged and patient. I waved her into the kitchen when the pasta was done, and we were quiet while we ate. Our eyes met over mouthfuls of spaghetti. It was somehow comfortable. We finished and talked for a while. She told me stories about her brothers and her friends. I laughed, and the bright loud sound surprised me.

Soon it was late, and the windows were black screens with bright pinpricks. I found old pajamas of Margaret’s. We brushed our teeth next to one another, our eyes darting in the mirror. We spat into the sink at the same time and both laughed a little. She got into the bed without hesitation. I slid under the blanket and arranged myself with care, trying not to bump into her. She shifted closer, laying an arm around my waist and fitting her head in the curve of my neck again. I debated, and then pressed a kiss into her hair and felt her smile against my chest. I lay awake listening to her breathing slow and steady, feeling the warm comfort of Margaret’s body against mine and the strange thrill of not-Margaret curling her fingers over my ribs. The tension held me stiff for a long time, and then it drained away and I relaxed into sleep.

It was late when I woke up, and Margaret was smiling in her sleep, her head on my shoulder. I eased her away and sat up, nudging her a bit. She blinked awake and I froze. Something was different, some new hardness in her eyes or a cautiousness to her waking expression. I panicked, thinking she had awoken in a strange place with me, a near-stranger, and was suddenly afraid. Her eyes lingered on mine and then she smiled. It was different, and I watched her for a moment, unsure. She said my name, and her voice didn’t lilt. I opened my mouth, but had no words. She drew in a deep shaking breath, and then she closed her eyes for a moment. She opened them and looked at me with a steady, new, familiar gaze.

I found my voice, and spoke over the ringing in my ears and the desperate gasp suppressed in my lungs. “Margaret?”

She nodded.

I held her for a long time and we both cried a little. Finally I moved, backed away from her enough to crane my neck down, and asked her if she wanted me to make breakfast. She nodded against my shoulder, so I tugged her into the kitchen. While I whisked and poured, she sat on the counter and watched me. It took me longer than usual because my hands were shaking. My arms jerked, I couldn’t hold them steady, and I spilled across the countertop. Margaret let out a tremulous laugh that startled me, and when my eyes jumped to hers she smiled.

We sat next to each other at the table, eating French toast from the same plate. Margaret nudged over to me, her arm against mine. The surprise and rush of emotion was still swelling in my chest, and it bewildered me. We distracted one another from breakfast. I kept kissing her lips, sticky with syrup. I couldn’t believe I had her back. I couldn’t believe she’d been gone at all.

Later, when we’d nearly fallen asleep piled against the arm of the couch, I knew we had to talk about it. I said, “Margaret, you were gone. I mean, you know what I mean, there was somebody else here and you weren’t here. Do you know where you were?”

She shrugged, looking down. She said that she had woken up in a crowded hospital with a bandage around her head and a broken arm. There were two strange men there she didn’t know who told her they were her brothers and tried very hard not to cry. They all said she had amnesia and she didn’t know how to tell them otherwise. She went home with her brothers and stayed in their house with their mother, who fussed over her and made her soup. She spent weeks curled in the tiny bedroom she shared with the stranger’s mother, trying not to show her bewilderment and her anger.

Margaret paused for a long time, and I pulled her over to me. Her body was tight, tension threaded through her. When I put my arms around her, she leaned her head against my neck very slowly but she was still frozen.

The family worried over her and her new sharpness, she told me, the knife-edges they thought the accident had thrust into her. Margaret wasn’t very clear what had happened, but she didn’t want to know the wounds inflicted on the body that was not her own.

I set myself to washing dishes. In the kitchen, the morning sunlight peeked in with golden curiosity. Everything looked the same as it always had. I cleaned up our breakfast and put the dishes away. It looked like nothing had ever changed.

The day passed quietly. We talked in low voices. When it grew late, she drew in a sigh and let it fall out of her, and then she told me that she wanted to sleep. We went into the bedroom and I pulled the covers over her, slid in behind her, and put a hand on her waist. She moved to me and held onto me, so I wrapped myself around her. Her breath wavered in and out, and I listened and wondered if she was sleeping.

The next morning, she woke up before me. I could smell the coffee waiting in the kitchen. She was sipping, reading the paper, as if we could be back to normal already. It’s possible that she was just getting back to normal, easing into our life again like an old sweater that still held her shape. I was the one startling at its touch on my skin, right when I had begun to learn to shrug out of it. I sat down anyway and picked up my section of the paper, drinking my lukewarm coffee.

Margaret got up then, unfolding her legs gingerly and stretching upward. Her voice startled me. “I might call Jenny in a bit.”

“Oh,” I said, nodding. “That’s a good idea. I bet she’d love to hear from you now that you’re back home.”

“Yes,” said Margaret, “Exactly.”

I heated myself some food and brought her a plate, then returned to the kitchen. The food was still too cold, but it didn’t matter. I ate without thinking, typing one-handed as I tried to catch up on work. Margaret didn’t eat at all. I heard her voice, peaks and valleys of muffled sound, from the living room. Once in a while the crack of Jenny’s laughter rang through the phone.

The day faded more quickly than it had promised in the bright harsh morning. Days went by like that, more than a week, and we moved around one another as though careful not to break.

“What was she like?” she said, once, into the silence. I only shrugged. I was in bed with a book and Margaret with her laptop, and I fell asleep while she was still working or reading. When I woke up, too early, she was drawn tight into a knot, her arm clenched over her body and her face turned away. I watched her for a while, wondering if she dreamed she was still trapped in a sleeping body that belonged to somebody else. I was startled when she woke and turned to me.

Margaret was half-lit in the dawn sun, with a familiar caress of shadow clinging to her face. She looked up at me and she said, “This feels weird. It’s all the same but so much has happened. Do you know what I mean? We’re not ourselves anymore.”

“Don’t be silly,” I said, too hasty, “who else would we be?”

She looked at me, a long solid gaze. “Somebody else,” she said.

I didn’t know what to say, so I let the silence grow stale between us.

Margaret curled up and turned away. My head ached. I sat on the edge of the bed, resting my hands on the crumple of sheets, and looked at Margaret as if she was a stranger huddled on my bed. I don’t remember lying down, just the surprising feeling of being awake unexpectedly from a sleep I hadn’t noticed taking me over.

The morning was warm and the sun coming in from the window was insistent as always.

Margaret must have already eaten, because the scent of maple syrup was hanging in the kitchen. I made cereal and ate while I read the paper, as usual. Margaret was busy with something in the bedroom. There were erratic shufflings and thuds, and I was afraid to investigate. When I had gotten to the Arts section she came into the kitchen. “Come in the living room, I want to talk to you.”

As I stood up my stomach dropped. In the living room we sat on the couch. Margaret handed me a piece of paper. I looked at her. “We haven’t talked that much about what happened,” she said, “and mostly I just don’t want to. It was too strange and too wrong. You got to know this other person, and I got to know her life. Now that I’m back, you know, it’s just not the same. It’s just not. I’m going to leave — ”

I tried to say something, though I don’t know what. Her words hit me and sound came out, an undignified shocked squawk. So simple a sentence meant so great a change.

Margaret’s mouth wavered. She might have tried to smile. “I know. But what else is there? I guess — no, listen, it’ll be okay. Really it will. We’ll both be who we are now, or something. I don’t know. I wasn’t expecting this. I’ll be back later, somehow, for the rest of my stuff. Listen. I know some things about the other person, whose body, the one you met.” Her hand fell toward the paper I was holding before she pulled it back. “It’s her name, the address, anything else I remembered that I thought might be useful. Don’t open it until I leave, okay?”

I looked down at the folded slip of paper in my hand and Margaret bent to kiss my cheek as she went by. The door shut behind her, the same click as always, leaving me alone inside. I sat for a long time in my living room with the sunlight pooling at my feet, holding hope in my hand.

Featured image: Edvard Munch, Young Woman from the Latin Quarter, 1897, The Art Institute of Chicago, edited

“A Ring With Rubies At” by Oma Almona Davies

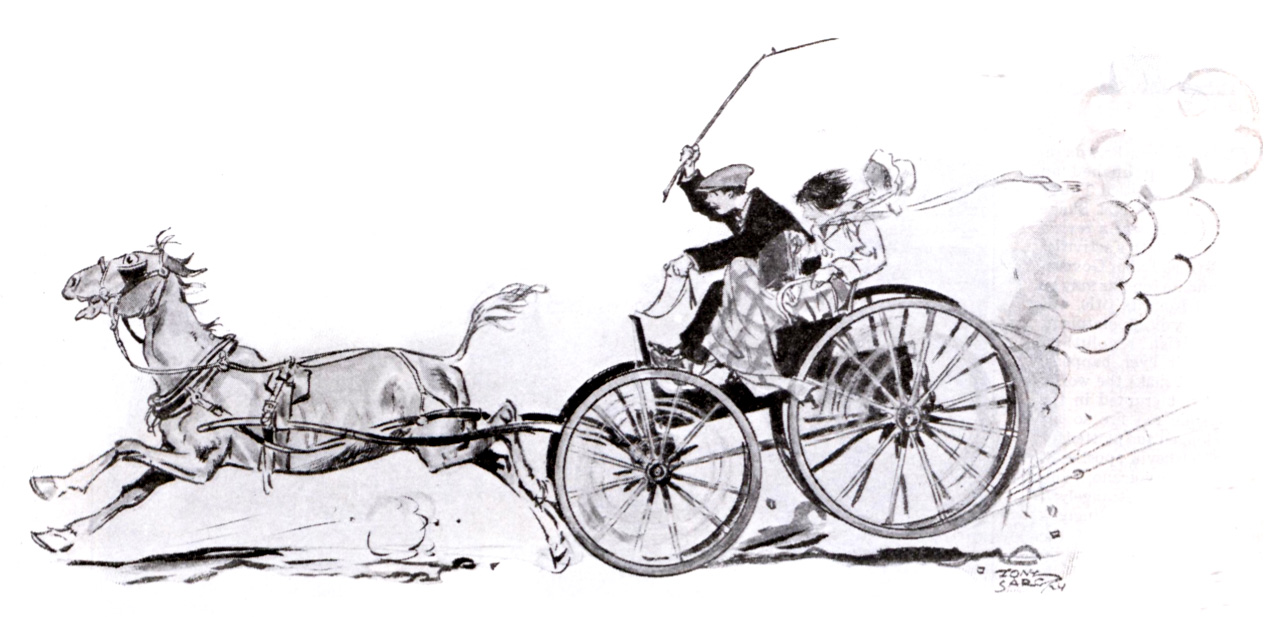

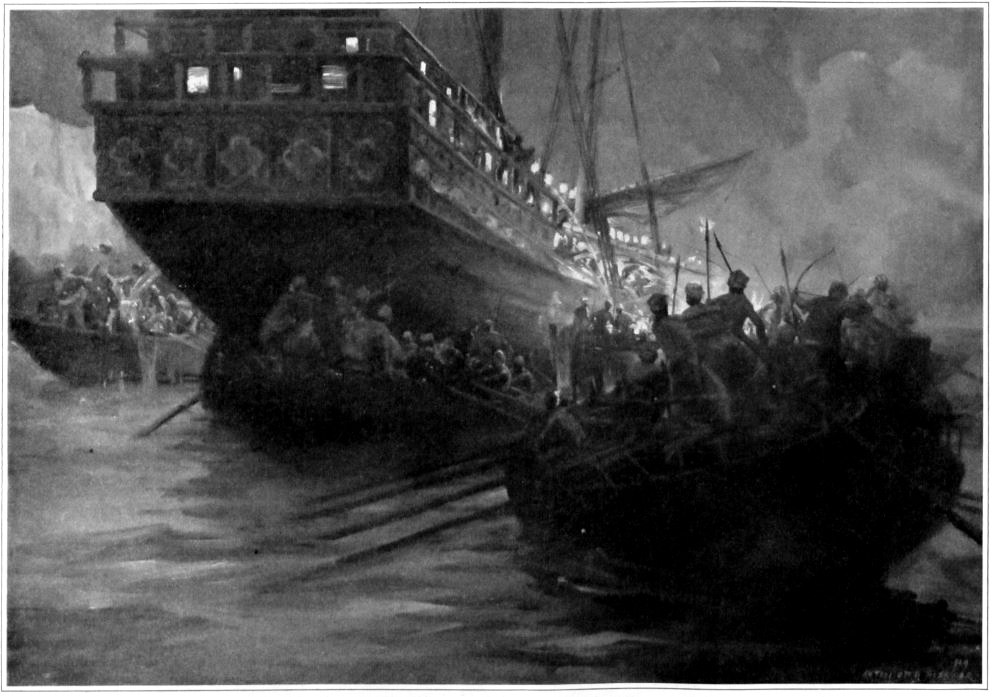

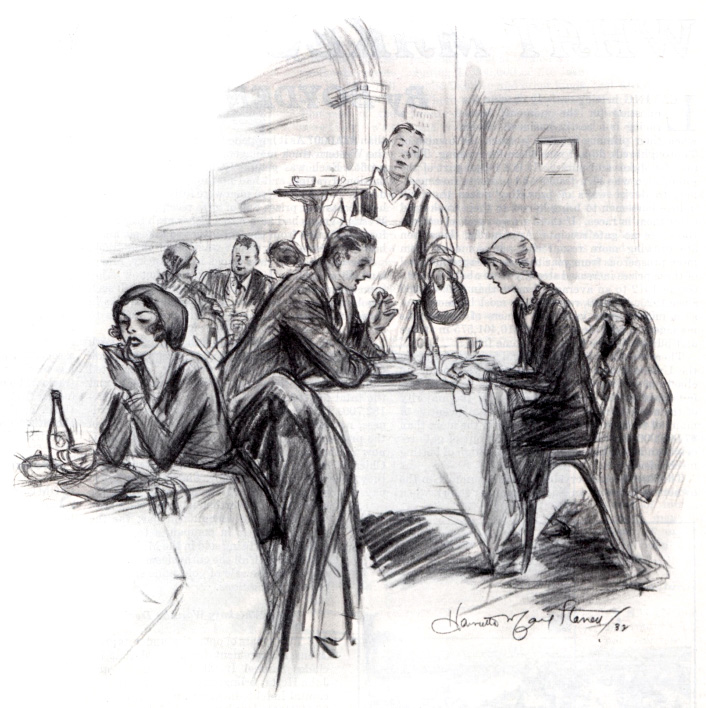

Oma Almona Davies was a regular contributor to The Saturday Evening Post throughout the 1920’s. For “A Ring With Rubies At”, we find her collaborating with the iconic post illustrator Tony Sarg to tell a story of romance, robbery, and danger, all centered around a magazine advertisement similar to those found in the Post at the time.

Published on May 10, 1924

Elisha Maice was on his way to kill the Hepple girl. His thoughts were as fiery as his hair, as deep as his blue, green-flecked eyes, as purposeful as the forward jut of his chin.

In amorphous hunch upon the seat of the top buggy, he pestered the horse’s rump with an ineffectual peach shoot while he passionately reviewed the previous half hour of his history. The galling thing was, of course, that he had been yanked upward by the neck scruff at the momentous instant in which he had decided his financial destiny.

For there he had been, a half hour before, with elbows taut upon the warm kitchen table, a 15-year-old man with twelve dollars and seventy-five cents banked in canvas bag upon his bosom, in travail as to whether he would become a cattle king or a hog baron. There had he been when he had rendered final decision in favor of the barony, the superior eagerness of the hog tribe to reproduce its own being the unanswerable argument in its favor. It had been at that climactic moment that Adam had leaped in, ox goad in fist, eyes wild.

“The bull’s outbusted the hind fence! You got to make me an errant. Make quick now!”

And as the potential baron, with hogs teeming by the thousand about him, had sat staring, he had been dragged from his chair, hoisted across the freezing ruts of the barnyard and dumped over the wheel into the top buggy.

“You got to git my girl from Schindler’s to Hoopstetter’s! Make hurry quick! And you fix a dates fur me — you tell her I’m a-settin’ up Saturday night agin!”

Oh, Elisha had protested at mention of the Hepple girl of course! He had started to kick out of the buggy. But Adam had plastered his eighteen-year spread of hand against Elisha’s middle and had pasted him against the seat again.

“Dast you! And you take good care to my girl or I’ll — ” And then, because he was Adam, and Elisha’s mother as well as his brother, he had grinned, rammed a huge paw into his pocket and had flung a dime upon the buggy seat. Then he had run, gripping his ox goad and hallooing to their father, who was already lunging toward the far end of the field.

In the clear flame of his anger against Adam, the bull and the Hepple girl, Elisha saw the problem of his life distinctly. His problem was to put into word and into action the fact that he was a man. Never before had he objected to being Adam’s younger brother — being anything to Adam had been enough. But now that he was being dragged into entangling alliances with Adam’s sticky girls, the relationship, as such, must cease

Here he was on his way — on Adam’s way — to the Hepple girl. He had to get her from her Schindler uncle in the village to her Hoopstetter uncle in the country. Why couldn’t Adam have let Schindler get her to Hoopstetter? And, back of all that, what did she want to come visiting around Buthouse County for anyway? If she was in a factory in the city, why didn’t she stay factor-ing then?

A groan escaped him as he beheld the red top of the Schindler house above its fir hedge.

From Schindlers of assorted sizes and sexes who swarmed into the side yard emerged finally the Hepple girl. She was supported toward the vehicle by a slender male Schindler with thin damp-looking hair. Supported is a carelessly chosen word, however; the young man’s legs seemed scarcely adequate to support his own frame — they gave the impression of being just on the point of swaying from beneath him. He nested his twiglike fingers about the girl’s elbow and she sprang lightly into the seat beside Elisha.

“This here’s Adam’s brother, ain’t? This here’s Elijah Maice, Herbie.”

The Herbie young man flicked an eyelash toward Elisha.

“Elijah, huh? Well, don’t let his ravens get you anyway! And don’t go forgetting your little city cousin while you’re out there among the hog raisers!”

“Oh, ain’t you awful?” giggled the Hepple girl. “Gid dup!” shouted Elisha. “Ain’t he awful yet?” The Hepple girl was the twitchy kind. She twitched at her glove, at a magazine, at the laprobe. “We ain’t relationed together. He just plagues me. He’s Uncle Jacob’s nephew, and I’m Aunt Mat’s niece.”

Elisha spat.

“Course he’s high educated that way. He’s got a decree, or whatever, at the law. He’s the leading and only lawyer at Heitwille a’ready.”

From the corner of his eye Elisha appraised that she was thin enough to be bounced out by a sizable rut. Suppose he maneuvered the wheels at just the right angle — she wouldn’t land hard, there wasn’t enough to her. Even if he did finally go back for her — if he did — the breath might be jolted out of her so that she’d be quiet anyway. He could see her sitting there by the side of the road.

What he really did see at that moment was another appraising eye. Upon him! A gray eye with an astonishingly black pupil. A pupil astonishingly penetrating!

He raised the reins high and slapped them down mercilessly. Old Bess flipped backward an outrages ear and lunged into a resentful canter. The Hepple girl bounced forward, then back—and settled closer to Elisha.

“Ain’t it kind o’ crispy though, now the sun’s gettin’ ready to set on us?”

Elisha heaved violently to his own corner. He felt the black pupils again turning toward him.

“It wonders me still,” pursued the Hepple girl, and her voice was soft now in meditation; “I thought Adam was sayin’ where he had a little brother. And here you’re a man a’ready. That does now make a supprise fur me.”

“Huh?” Elisha snorted, and was immediately sorry. He had made an iron resolution to suffer in silence his three miles of humiliation.

“Yes, I would guess anyhow! But mebbe he was playin’ off a joke on me. Or else, was you, mebbe, his big brother?”

“He ain’t got but one,” grunted Elisha. He surreptitiously glanced down the length of his arm, flexed its muscles. His secret shame had always been that he was not huge, like Adam!

“Now me, I’m so runty that way,” sighed his companion.

“You are that,” muttered Elisha.

“Course a body can’t help fur their size. But I guess that’s why I always take to big men mebbe.” Elisha shuddered. “Well, and women too. Aunt Mat always says, ‘My, I wisht if I wasn’t more’n two hunert, so I could be stylish like you,’ she says. But I say back always, ‘Well, what does it fetch to be stylish? Look oncet at Cousin Herbie. He might be stylish, but he’s awful skinny. Them kind don’t make nothing with me. I like fur to see ‘em heartier and more, now, comfortable lookin’,’ I says. ‘Comfort yet is what makes with me,’ I says.”

Elisha looked down distrustfully at an extremely pointed shoe slanted upward from beneath the robe. His companion immediately gave a wrenlike nod.

“I know. It looks some squinchy. But it ain’t. I’m just natured to that shape a’ready.”

Elisha again went sharply in search of his breath. What was this he had in the buggy with him anyway? He had never seen such swift reaction, such uncanny divination. He had always thought you had to tell a girl anything twice over before she got it. And here, almost before he had a thought, she was expressing it for him! And that foot now — was it possible that a woman’s foot really did grow into a point? Could it be that a girl did quicken into some strange new thing somewhere along? That she wasn’t just a meager edition of a man, weaker in both mind and body?

He squared heavily about and looked full at the Hepple girl. She twitched lightly about and looked full at him. Her eyelashes rayed out, very black and very long; their tips seemed caught together by twos and threes — caught together — caught — He gasped; his foot jerked heavily upward as though from some entanglement. The jerk pried loose his eyes.

He wouldn’t look at her again. What was the matter with him? A rein dropped from his demoralized fingers. He swooped after it. And as he came up, something slowly pushed his head around so that he looked at her again. Her eyes were still upon him. Her very soft, very red lips parted slowly, slowly curved.

He definitely clutched at anger. He grabbed the peach shoot and sliced blindly. It broke over the dashboard, dangled. He hurled it away and hissed wrathfully after it.

“What you intrusted in?” Should he answer her? “Poland Chinas,” he grudged. “Me too! I do now take to them Oriental things till it is somepun supprising. My, ain’t you up-to-the-minute though?”

“Pigs!” shouted Elisha. “Hogs! Boars!” She was a dopple after all! Didn’t even know Poland Chinas!

She considered. Then she gazed at him, gently forgiving.

“To be sure, pigs. Polish Chinas. But they come from China first off. And if they come from China, they’re what you call it Oriental, ain’t not?”

Each hair upon Elisha’s head rose in fiery curiosity. “China, still? From acrost the oceans over?”

The Hepple girl nodded decisively. “In such ships oncet.”

Elisha pondered this revelation of porcine genealogy. The girl gave a little sigh.

“But, anyways, what does it make? This here is what makes with me: Fur to find somebody where has the same intrusts like what I have a’ready. I do, now, take to such little pigs. I can’t otherwise help fur it. And I would bet, now, you’ve decided to go into pigs!”

Breath-taking! Elisha leaned back somewhat weakly.

“Well, anyway,” he admitted, “I took the prize for Juniors at the Grange two months back a’ready. Twohunert-and-sixty-pound shoat. Ten dollars.”

“Ten dollars still!” gasped his companion. “Since I am born a’ready, I ain’t hearing of nothing so intrusting!” She snuggled closer.

Elisha tipped his cap rakishly. He tossed off, “That ain’t nothing. I’ll git mebbe twenty, twenty-five, more on her yet. Till it comes next week, pop will be loadin’ stock fur the market onto a box car, and I’ll be a-fetchin’ off my share alongside the other — the other men.”

Then said the Hepple girl an amazing thing. “Before ever you was turnin’ in at Schindler’s, I seen it at you. Yes I seen it at you where you was one of the money men of Buthouse County a’ready.”

And she wasn’t joking! He swung upon her quickly to catch her. She was gazing up at him as innocently as a babe, and as helplessly, as helplessly. Her lips were parted as in breathless adoration, her eyes upturned deep pools, into which one might slip — or plunge —

“Whoa!” yelled Elisha, and subdued his steed from a gentle trot to a walk. “Whoa, anyway! What do youse want to make such hurry fur?”

His left side was growing very warm; oh, very! The girl looked bony, but she wasn’t. She flanked him closely, softly, like such a hot- water bottle; or, no, hotter, hotter, like one them mustard plasters now. His heart thump-thumped, thump-thumped. She lay against his heart! He had a sudden conviction, all pain, all pleasure, that he could not move if he tried! He was terrified, he was paralyzed; he had never been so desperately happy in his life.

As though soft veils had been laid over his ears, he heard her voice coming up, coming up, as though from far below: “Yes, well. I guess I would up and give it away if I would ever get such a ten dollars. Yes, I guess I would go to work and make some such inwestment at friendship, like I read off somewheres. And that would be awful silly, ain’t?”

“Yes,” agreed Elisha hoarsely.

Elisha, in fact, was in mood to agree with everybody. A half hour later when Mrs. Hoopstetter swam into the periphery of his bedazzled vision, he agreed with her. Mrs. Hoopstetter, with hairpin antenna emerging from the black coil upon the top of her head, her rounding form incased in black calico with red polka dots, bore an unmistakable resemblance to a potato bug as she ambled toward them from her kitchen door.

“Well, was this, now, Cory Hepple? Ain’t you growed though, since you was a baby a’ready? And if this here ain’t Elisha a-fetchin’ you! Come insides and set along fur supper, Elisha. The Wieners is all made and the coffee’s on the boil.”

Still later he agreed with Cora Hepple when she indicated that he was to sit down beside her upon the settee and to devour with her the magazine which she had carried from the Schindlers’.The name of the publication as it was emblazoned above a polychrome pirate rampant upon its cover was Up to the Minute; and its date was the month previous.

That Miss Hepple was a devotee of literature might have been inferred from the general indication of wear and tear upon the publication; but she disclaimed any tendencies in this direction when Elisha cast a gloomy eye upon it and gloomily shook his head in answer to her question.

“Nor me neither,” she confessed promptly. “I ain’t addicted to readin’ off just one word and then another. That there’s a waste of time, ain’t? But I do sometimes go to work and read what it makes at the adwertisements. Now, fur instinc’, it wouldn’t wonder me none if we was to run into some such pigs over behind.”

Fascinating as were pigs, however, they were not so fascinating to Elisha at that moment as the fingers which were flying in search of them. The lamplight coruscated over the nails which tipped them like they were—well, like they were freshly shellacked, now. He drew his brows as he gazed from them to his own, dull and spatulate, and finally queried bluntly: “What is it at them? Warnish or whatever?”

She looked up at him inquiringly, then laughed softly, tipping up one shoulder, then the other.

“Oh, I’m just natured that way at the nails. It’s fierce, ain’t not?”

“Yes,” breathed Elisha. Pointed feet — shining nails. He slid from her. And why not? It is an awesome experience to discover a new creation.

She uttered a sharp exclamation, laid the magazine flat upon her knees and placed five of her amazing finger nails upon her heart.

“Och, my! That there makes me dizzy at the head! Why, it’s just what I been always dreaming about!”

Elisha looked down at the page. He saw nothing remarkable. “It ain’t nothing but a ring,” he said.

“A ring!” gasped Miss Cora. “A ring with rubies at!” She thrust the publication into his hands. “Read it oncet!”

Above, below and surrounding a particularly angry-looking ring from the stone of which fiery rays darted to the bounds of the column were the words:

STARTLING GEM OFFER

Our exclusive MILLENNIUM RING, known to satisfied thousands. Blue-white stone, perfect cut, set in elegant white-gold cup, surrounded by

CHOICE OF EMERALDS OR RUBIES CREDIT TO OUR FRIENDS This means you!

EXTRA SPECIAL

at $29.50Simply enclose $10.00. Balance $2.50 per week. Our investment in friendship. We take all chances

LIMITED SUPPLY ORDER NOW

Elisha shook his head darkly and handed back the magazine.

“Say, now,” he warned, gazing down at the innocent little creature curled up beside him, “don’t go fallin’ ower this here! It might be some such trick in it. Them city sharpers — ”

But look who it is a’ready! The Old Honest Goldsmith, H. Chadwick, Inc. I’ve knew about Mr. Inc since I was born a’ready. But what does it make to talk?” She spread her ten tiny empty fingers in a gesture of resignation over the piercing rays of the ring. “It ain’t nobody where would go makin’ such expensive inwestments at friendship just ower me! Eut och, my! If anybody up and got me such a ring with rubies at I wouldn’t have eyes for nobody else, it would go that silly with me. I have afraid anyway — ”

But she was not so smitten with fear at that moment as was Elisha. He sprang up, kneecap cracking. His body slanted tensely toward the closed kitchen door, through which a voice was thundering:

“What does he mean by somepun like this anyhow? Lettin’ the cow to milk fur me! It should give a good thrashing fur that one!”

“Your pop!” gasped the girl with lightning intuition.

Elisha did not pause to identify his parent verbally. He was already wresting open a door on the opposite side of the room. He whizzed through the chill dank of a parlor, wrangled a huge brass key at the ceremonial front door and zoomed out into the blackness of a porch.

“I got to go. It’s gittin’ late on me,” he clattered back over his shoulder.

But he had not counted upon the celerity of his hostess. She was there beside him. Even as he landed upon the top step she thrust something beneath his arm.

“Take it along with! We ain’t looked fur them China pigs!”

Elisha had no need to urge upon old Bess that time was the essence of their contract; she had not yet had her supper. She legged off the mile and a quarter between the two farms with such impatience that Elisha had fed her and had bedded both her and himself before he heard a door slammed in paternal wrath beneath him. He lay quivering in the bed beside the sleep-drenched Adam until he heard his father’s footsteps clanking off to their own room; then he nested down with a great sigh.

It was long before the boy Elisha really slept. And yet, was it the boy Elisha who lay taut between the blankets that night, his forward jut of chin thrusting upward into the crisp air, his deep eyes matching the depth of shadow in the room? Had not the boy Elisha gone to sleep, beyond recall, two, three hours before? It was a naked soul, an elemental, at grips for the first time with the most powerful of the powers of the air. For assuredly it was not a man, this skinny thing which had finally much ado to keep from blubbering, from clutching at the big warm Adam and blubbering that he hadn’t meant to do it, he hadn’t meant to take Adam’s sweetheart from him; but she just would have him, she just would!

Between his tossings, as he lay still-eyed, came again and again a memory seemingly detached from all he was thinking and all he was feeling: A long, long time ago when he was six and Adam was nine, the two of them, stumbling down the hill, behind their father, from the new grave under the beeches — Adam clutching his fingers until they hurt and whispering thinly: “You got me anyway! You got me anyway!”

And this was the Adam the was hurting! This was the Adam he was robbing!

He awoke, as usual, to the vigorous rattling of the stove in the room below. Adam did everything, not quickly, but vigorously. No brighter pans than Adam’s in any kitchen of Buthouse County; no straighter furrow in any field. No better corn cakes turned for any table; no cleaner garden patch behind any house. It always had been rather fun to keep house with Adam; it had seemed no woman’s task as Adam had carried it on, with slashing broom and swishing brush.

But today it was no fun. Elisha slunk about, with eyes down. Oh, he was heartbreakingly sorry for Adam!

And yet his heart beat with terrific triumph. Triumph that took him spasmodically by the legs and flipped him into a handspring. Triumph that took him by the wrist and made him shy a hatful of duck eggs, one by one, against the corncrib.

But there was no compromise in him. The jut of his chin was thrust definitely toward manhood — manhood symbolized, curiously enough, by that girl a mile and a quarter distant. A mile and a quarter? A world distant! And time — this was Friday — tomorrow Saturday. Well, Saturday night, then.

Upon his shoulder fell a heavy hand.

“Now, what about Saturday night?” demanded Adam. “Was you tellin’ her a’ready I am keepin’ comp’ny with her Saturday night?”

Like a bronze frog Elisha squatted, motionless. The hand twisted impatiently. Elisha slowly reached for a weed, slowly plucked it.

“It’s somebody else — settin’ up, keepin’ comp’ny — Saturday night,” he brought out. The hand jerked him, dangling slantwise, to his feet.”Somebody else?” roared Adam. “Who else, then? Answer me up now! That sleazy Schindler?”

“She — ain’t sayin’.”

“She better not be sayin’!” gritted the terrific Adam. When he knotted his fist like that the wrist tendons whipped out like live cords. “He’ll git the right to git his neck twisted off fur him.” He stalked away, kicking the clods.

Elisha oozed down upon the ground. He gazed after Adam, then he knotted his own fist and stared down upon his wrist; there were no cords there! Well, maybe, just maybe, he wouldn’t interfere with Adam, Saturday night. But at that moment between his young ribs began to creep and whimper an alien thing, a spawn of distemper which was finally to strangle—and strangle—his love for Adam.

Hot of eye, hot of heart, he watched Adam on Saturday night as he bathed in the zinc tub behind the kitchen stove, as he covered his long clean muscles with splendid raiment, as he carefully parted the bronze glow of his hair and carefully curled up the lopside of it over his finger, as he donned his hat with slow deference to this same curl that it might follow the upward tilt of the felt. Adam never knew that when he closed the door upon his festive person, a man with the ache to kill shot to his feet with clenching fist and kicked murderously the leg of the table with the brass toeguard of his shoe.

But — he couldn’t endure it! He cast a quick glance upon his father mumbling over the livestock quotations, raped his hat and coat from their nail and let himself out of the door. Down the lane crisped Adam’s wheels upon the frozen ground; down the lane sped Elisha. He caught the tail of the buggy at last, jerked along agonizedly with it for a moment, then with a mighty heave landed in a clutching heap upon its narrow tail.

Ignominious, of course, jolting along back to back with Adam, the tailboard bruising into his flesh with every rut. But he was going, at any rate; he was getting there!

He got there, and he crouched like a the Hoopsetter wagonshed while Adam blanketed old Bess. Like a mouse scurried to the window of the living room.

There, there she was—upon the settee just as he had held her in memory! The light from the hanging lamp made a nimbus of her dark curling hair. Her little feet, those pointed feet, were tipping gently this way and that. And her eyes, those wide innocent eyes, were also turning, first this way, then that. Upon whom? Upon the male Schindler and upon Adam, upon a disgruntled Schindler and upon a glum Adam with arms upright like stanchions upon his knees. There they sat, the three of them; and outside, loving, hating, Elisha. Outside, feasting, starving, Elisha.

Outside, that was it. Shivering’ for a quarter of an hour, there, outside. With a hard gulp he swung from that window at last. He had determined what he would do. He would do that which he had told himself for two days that he could not do.

He could not do it fast enough now. He lunged into a run, the aroused Hoopstetter hounds in full yelp behind him. The whole universe seemed in clamor. He liked it. It seemed right, considering the momentous thing he was about to undertake.

The house was dark, as he had expected, but he paused for an alert moment inside the door, his ear cocked cannily upward toward his father’s bedroom. Then he tiptoed into the parlor and abstracted from the paternal stock of stationery between the leaves of the family Bible an envelope, a sheet of paper and a stamp. There was no need to withdraw from the lair beneath his own mattress the phrenetic pirate guarding the Startling Gem Offer of H. Chadwick, Inc. Did he not know by heart every syllable of the Old Honest Goldsmith?

Under slowly weaving tongue Elisha composed his first business letter, which for brevity has probably never been excelled in all the annals of financial correspondence:

Heitville Rural F D

Dear sir Mr Inc I send you still ten dollars. You send me Milennium Ring A3035 as per

stricly confidential. With rubies at.

yours truely

ELISHA MAICE