Will Holograms Help Us Grieve?

Long before Kim Kardashian West made headlines for being gifted a hologram of her deceased father for her 40th birthday, a panel session at South by Southwest Interactive, an annual conference for tech innovators, predicted innovations like this as inevitable. As the panel’s program text read: “Grandma passed away last year, but she’s coming back for Thanksgiving dinner this year. This may sound like a horror story,” it continued, “but it could be the future of family reunions.”

The 2015 conversation, titled “HoloGramma: How Tech Can ‘Bring Back’ Our Departed,” discussed how, through extreme technological means, people would one day maintain not only the memory of a deceased loved one—but their very presence in the home.

Whether this concept—that grandma could be switched on, say, in the living room whenever you wanted to see and talk to her—feels creepy, fascinating, or the uncanny mixture of both, consider this: In the modern age is such an idea that shocking? That is, don’t we encounter and interact with the pixelated presence of the dead all the time? For instance, I can make coq au vin at home, guided by an old YouTube video of Julia Child while listening to Prince. Or if my husband and I turn on the morgue that is Turner Classic Movies, we will inevitably pull open the IMDb app to answer questions about the parade of people from the past appearing on the screen. To live a modern media-saturated existence means to swim in ectoplasmic estuaries of life and death, in which living bodies regularly mingle with specters of the long-gone.

Granted, watching Bogie & Bacall is an experience with much less emotional investment than, say, if a “HoloGram” of my late father drifted into the room (though for Bogie & Bacall’s kids, To Have and Have Not may be simply a cruelly titled home movie). Degrees of affect aside, though, many scholars claim that the very experience of any electronic media technology is an essentially spectral encounter. The disembodied voices on radios and the luminous figures on cinema screens constitute what media studies professor Jeffrey Sconce equates with hauntings, writing about a “media occult” surrounding the “seemingly ‘inalienable’ yet equally ‘ineffable’ quality of electronic telecommunications.” Communication scholar John Durham Peters claims that modern media is infused with a “spiritualist tradition”—one we participate in as readily as grieving people in 19th-century America and Europe sought out the services of spiritualists, professionals who claimed to be able to conjure the dead for a brief chat.

It is, as Peters argues, from those very practices of communing with the dead via mediums that we derived our present-day terminology about communication via media. By participating in social interactions designed by and for electronic media, we become more comfortable with these essentially spiritualist encounters. We learn to live with their summonings and ghosts.

Rather than ectoplasm or spirit-stuff, our technical ghosts comprise combinations of words and sounds, fine-tunings of imagery and ideology. Stage celebrities and film stars, TV icons, and pop stars—they are people, of course, but most of us don’t interact with the actual person, with their flesh body. Instead, we participate in encounters with nebulous packages of literal imagery and figurative image, of carefully coordinated public appearances and deftly staged concerts. Philip Auslander, a performance studies scholar, argues it is not the actual celebrity but their performing persona that fans have “the most direct and sustained access” to, not only through their work but also their public messaging.

This persona is carefully and socially managed. A pop star may control much of it, but not all of it. Managers, publicists, handlers of various stripes have a hand in shaping it, as do audiences and fans. So the persona is not the real person nor the fictional character; it’s the liminal figure in between—the one modern media, by its spectral nature, is adept at presenting, projecting, and protecting. And when a public figure dies, their persona continues to be managed posthumously by handlers and fans. Robert Johnson, Woody Guthrie, Mama Cass, Elvis Presley, both dead Beatles, and Tupac Shakur are just a few of the hundreds of artists who sold previously unreleased or even newly crafted records while dead, often selling more recordings from the grave than they did while alive. Orson Welles’s “final” film was just released two years ago. Fans revel in discoveries of “lost” art, interviews, or other ephemera that returns some aspects of a late celebrity’s persona to circulation through the same channels they haunted while alive.

In recent years, though, the celebrity’s posthumous presence has been taken one step further. Numerous deceased pop-music figures—from Roy Orbison to Buddy Holly, Michael Jackson to Whitney Houston—have been resurrected for new performances via animated digital simulations that are projected onto concert stages. These sophisticated animations and apparatuses present likenesses of the performer as if they were present in body as well as spirit. They are staged in a manner that highlights that illusory presence, often with real people on stage interacting with the spectral imagery.

As a former music journalist and current researcher in communication and science studies, I have examined and written about the specific technical means for the production of these “holograms”—an inquiry that began when I received a 2011 press release about “the world’s first virtual pop diva,” a Japanese anime-style character named Hatsune Miku, who has no corporeal existence but who nonetheless headlines concerts in crowded arenas. When I attended a “live” concert by this digitally projected character, in a large theater packed with a thousand rapt fans singing along, the pop-music critic in me wondered whether years of honing criteria for the evaluation of human performance on stages had just been made irrelevant. The scholar in me, however, recognized another intervention of technology into social norms and rushed to connect history and theory to explain the new experience.

The American fountainhead of this trend was Tupac Shakur, who—16 years after his death—headlined the 2012 Coachella music festival. Before an audience of nearly 100,000, the real Snoop Dogg and the real Dr. Dre introduced the “not real” 2Pac, who materialized on stage and performed two songs (one of which had been released after he died, implying a chain of production unbroken by pesky mortality). News media ate up the spectacle, and Twitter went into a twitter.

My own analysis of spectator reactions posted to Twitter within 24 hours of the Tupac spectacle shows that fans initially experienced an expected uncanny unease but then quickly settled into the experience of a reality they were accustomed to through a lifetime of modern media hauntings. What spectators saw were familiar bits of Tupac’s living persona that had been cobbled together and reconstituted for presentation within a musical context that was, in every other aspect, perfectly normal. He looked the same (face, body, trademark tattoos and Timberlands). He sounded right. He boasted and swaggered and performed. The digital Tupac gave little reason for derision (though there was some) or angry cries of fakery (though there were a few) because it provided just enough ingredients from the working persona that fans still recognized from Tupac’s lifetime. No one ran screaming from the festival grounds; they knew or were able to determine that this was a ghost and that it was (somehow) technically produced. They also already knew how to separate the persona from its material media, applying it to a technology almost as easily as they had hung it on his flesh body. By the following morning, fans were speculating (jokingly, but maybe only by half) about a new album by “2.0Pac,” where he might have gone to eat after the show, and who he would soon be dating. They were happily haunted, already living with the dead yet again.

It’s not the first time technology has promised and delivered a mediated afterlife. For centuries, gadgets and gizmos have been invented and sold to feed into on our age-old questions around mortality—about what lives on after we die and how we might maintain contact. From the basic wood-and-glass planchette (later, the Ouija board) to Thomas Edison’s mused-about but never-built “spirit phone” (which was to dial up the departed), these frauds and fantasies, respectively, have offered mystifying possibilities for contacting or manifesting the presence of the dead. The performing hologram is the latest materialization of mediated spirituality—a new iconic image, like those of saints, as philosopher Matthew Harris has written, wielding power “much in the same way that a relic has power for the religious devotee.”

These performing hologram systems are simply HoloGramma writ larger. They are technical projections of an embodied simulation of the dead back into a real space for new social interactions among the living. They are media doing what media do—presenting a person’s persona within specific contextual frames, regardless of where that person’s body might be, or if it might be.

The idea of holographic grandmothers is simply a dimensional extension of existing media interactions between the living and the dead. While a Tupac or Kardashian hologram is currently beyond the means of most, the average person’s persona imprinted across digital platforms is not buried as efficiently as our body, nor does it decay as swiftly. This data may not only live on through the networks, it may also continue to act. Which suggests the future of posthumous presence begins in the ways we currently organize and nurture, while we live, the mediated elements of persona that will survive us—and that may be crucial to the grief and mourning of loved ones left behind.

This is already happening. Each March, for instance, Facebook friends and I still wish a former colleague a happy birthday, even though he’s been deceased for several years. He responds, too—or his sister does, anyway; she manages Brian’s online afterlife, posting alongside his eternal photographic smile.

It’s no fireside chat with HoloGramma, mind you, but every knitted scarf begins with a few innocent strands.

Originally appeared on Zócalo Public Square. Primary editor: Jackie Mansky; Secondary editor: Eryn Brown

Featured image: Peshkova / Shutterstock

A Millennial Leaves His Phone and Goes into the Woods

On normal mornings, I wake up and immediately grasp my cell phone from its resting spot next to my pillow and Google the previous day’s new Coronavirus cases. At least, that’s how it’s been for the past few months. But when I woke up last weekend, there was no frightening uphill chart to behold, because there was no phone. I rolled over and gazed out at a blur of treetops through a tent screen. I put on my glasses and realized I was looking over a foggy valley, that the camping spot I had stumbled onto late the night before sat on a cliff perfectly situated to receive the sunrise.

When I decided that I would leave my phone behind to disappear into southern Illinois’s Shawnee National Forest for the weekend, my roommate was concerned. “Why would you do that?” she asked. “What if you get lost?” I told her that people don’t get lost in America in 2020. “That’s because they have cell phones!” she countered.

I would hesitate to claim I have smartphone addiction, but I’ve been known to pass hours slumped on the couch, scrolling through yoga videos I might one day try, bruschetta recipes I might make, far-flung destinations I might visit. I’ve lingered a little too long on Twitter during work hours (don’t tell my editor), and there was that one blur of a weekend that was entirely lost to the engrossing Bloons Tower Defense 6 game.

Of course, I’m not alone in my tendency to zone out and fall headfirst into the time-consuming trappings of the device. According to several surveys from 2017, Americans, on average, spend from three to five hours each day on mobile devices. For younger people, the number is even higher. Our collective panic over wasting time on our phones has created space for some savvy panaceas in the private sector. Tech rehabs have cropped up, self-help texts for more mindful phone use abound, and Google has even gotten in on the action with their launch of Digital Wellbeing. The app gives users a rundown of their screen time and offers nanny-style blockers from too much browsing and scrolling.

I wasn’t seeking such a formal tech break, though; I only wanted to test out the cold turkey method for a weekend. So I dug out my backpacking gear from the back of my closet, gathered a few books (Birds of America by Lorrie Moore and Dept. of Speculation by Jenny Offill), and prepared to realize some long-held plans to visit a jewel of the Midwest: the Garden of the Gods Wilderness. I told my dog Calliope where we were going, and she seemed indifferent.

My loved ones insisted that I at least keep my phone in the car. I could stash it away and keep it turned off, they said, as it could be necessary for an emergency. I was travelling four hours away to an unfamiliar area, and my Prius did have about 550,000 miles on it. I might have something to prove, I thought, but I’m not stupid. I resolved to hiding it in the trunk.

What would it be like, I wondered as I followed my handwritten directions across hilly southern Indiana, to spend a few days with only my thoughts and my dog? On a local radio station, the deejay gave a shout-out to her “Facebook friend of the week” and directed listeners to her page to check out a video she’d posted of a cute animal. I lucked out and found an Ella Fitzgerald CD in the glove box left by the previous owner.

The Shawnee National Forest, stretching across southern Illinois between the Ohio and Mississippi rivers, covers almost 300,000 acres. The sandstone cliffs, bluffs, and hoodoos of the Garden of the Gods were created more than 300 million years ago when the region sat on the north shore of an enormous sea. The continental glaciers that carved much of the state into flatlands stopped just short of the Shawnee Hills, allowing these ancient structures to remain intact and providing views unlike anywhere else in the Midwest.

There is also plenty of wildlife — both dangerous and benign — to be found in the forest. Box turtles, raccoons, opossums, hawks, vultures, and squirrels are everywhere. With some bad luck, you might stumble onto a cottonmouth, copperhead, or even one of the elusive rattlesnakes, the timber rattler or the massasauga (all the more reason to refrain from hiking-while-texting). There are black widow and brown recluse spiders as well as the velvet wasp, a wingless ant-looking bug that delivers “the most painful insect sting in the world.” Encountering any of these spine-tingling creatures is fairly rare, however, and dying from any of them is all but unheard of. That’s what I told myself as I marched through the woods in the middle of the night, my flashlight casting quick, darting shadows on the vast expanses of poison ivy.

Since Shawnee is a national forest, it’s free to camp anywhere you’d like, as long as you maintain some distance from trails and waterways. You can often find unofficial campsites where others have constructed stone fire rings and makeshift seating. On the second night, Calliope and I stumbled upon such a spot, and I built a fire to cook ramen while she collapsed nearby and stared at me thinking, what in the hell are we doing here?

What were we doing there?

I had scratched the long-disquieting itch to get away from it all, but at first it seemed I had traded isolation in my home for isolation in the woods. Camping alone, or with a furry friend, is a surefire way to strip down the distractions of daily life and spend time thinking about where you are and where you’d like to be, both literally and metaphysically. Going without a phone is akin to constant meditation, at once trapped with your own thoughts and liberated from the fast lane of the information superhighway.

There has been some research into the effects of “problematic smartphone use”— particularly as it applies to young people and social media. We know that poor emotional well-being and smartphone overuse are often connected, but causation is difficult to prove. A study released this year in Cyberpsychology looked at “FoMO” (fear of missing out) and PSU (problematic smartphone use) as two separate but connected factors affecting emotional well-being. The findings suggest that it can be a sort of a vicious cycle, with negative feelings arising from both “FoMO stimulating online relationships at the cost of offline interactions and physical symptoms associated with excessive smartphone use.”

The study, along with many others, lends credence to something many of us innately understand: when I waste too much time on my phone I feel bad afterwards, and when I feel bad, I retreat to the comfortable, familiar habit of slingshotting angry birds and scrolling through my ex’s gym selfies.

Without a phone, I noticed more of the world going on around me, like the yellow butterfly that landed squarely on my dog’s nose and stayed, flexing its wings, until she shook it off. I noticed the complete silence that overtakes the woods at dusk. It comes right after the birds’ chirping has tapered off and right before the crickets and katydids begin their nighttime cacophony of sounds. I sat and listened, feeling still alone but also incredibly peaceful — the kind of feeling I might be able to define perfectly by whipping out my phone and Googling an antonym for “stress.” The forest offers this to anyone willing to turn off and tune in to the natural world.

Could there be a way to experience this kind of quiet and focus without hiking for hours and pumping creek water through a charcoal filter?

On Sunday, I slept in to some unknowable hour and then packed up my things, planning to make the trek straight back to the car and drive immediately to the nearest store for a sugary canned coffee drink. Calliope and I set off, making our way through the trails we had hiked in on. When we came to a familiar four-way intersection, I consulted the map and continued on a trail that, I was 90 percent certain, would take us back to the car.

After an hour of hiking deeper and deeper into the woods, I realized we were on the wrong trail. It curved around in a disorienting fashion, and led to a steep uphill climb that I distinctly did not recall from the hike in. Then we found ourselves climbing uphill even more, and yet again. Turning around the bend of every curve brought the excruciating sight of more ascending trail. How high could we possibly be going? I thought. It’s Illinois!

Then, we turned a new corner to find a clearing. Approaching it, I saw that it overlooked the valley in which I’d spent the past few days camping. It had to be the highest point in the park, with a view of the forest and even the farmland past it for miles. The dog walked right up to the edge and looked over, and I realized that I hadn’t known for years whether she was afraid of heights because I hadn’t taken her to any cliffs before. She stood proudly before her domain, creating the perfect opportunity for an adorable (hypothetical) Instagram picture. There would be no evidence on social media of the trip: no livetweeting, no 360-degree videos, no deluge of Facebook likes from jealous friends. The whole thing would have to be archived in my own mind.

When we finally found our way back, we were practically crawling to the doors of the Prius. Driving home, I reflected on the merits of “unplugging,” and what exactly the big takeaway could be from such a short vacation from tech. Would I arrive home and immediately revert to my old ways of binge-reading Twitter drama and feeling phantom phone vibrations on my left thigh every 10 minutes? Would I even remember this vacation if I couldn’t be reminded of the beauty of the Garden of the Gods by Facebook Memories in years to come?

What I will remember is the noticeably heightened sense of focus and peace I felt in the woods. If you give up the smartphone for a few days, you might become hyper aware of just how long it has been since you lived without one. But realizing that it is possible can inspire you to take more breaks from your smartphone day to day. Leave it at home and go on a long walk, or pledge to trim down your notifications. You might be surprised by how much you notice when you aren’t always grasping for your phone. And we could all use more pleasant surprises.

Featured image: Shutterstock, by Oleksandr Koretskyi and A-spring

Contrariwise: Let’s Stop Bashing Millennials

“I believe that the abominable deterioration of ethical standards stems primarily from the mechanization and depersonalization of our lives — a disastrous byproduct of science and technology,” said Albert Einstein in 1946, as the first wave of baby boomers entered a new, post-war, consumerist culture that coincided with the rise of mass media. Those coddled, Dr. Spock-reared bundles of joy couldn’t have possibly known they’d grow up to be a cranky senior population complaining about their grandchildren’s addiction to smartphones. In fact, they formed the habits millennials would soon inherit.

Ever since the advent of the radio, older generations have complained about those damn kids and their new-fangled gadgets, fearing media consumption would lead to the degradation of society. In the 1950s, you may recall that satirists referred to TV as the idiot box or boob tube.

Let’s be honest — we’re all addicted to technology in one form or another unless we’re living off the grid.

Fast-forward to the present day, and the generational divide appears greater than ever as baby boomers and millennials trade digital blows in name-calling — from “snowflake” to “OK, boomer” — unaware that they’re more alike than they realize. A recent survey conducted by the Pew Research Center showed that while 93 percent of millennials own smartphones, baby boomers are not far behind at 68 percent with a rapidly growing adoption rate. Seventy years after television invaded our homes, we’re all staring at our screens, and now we’re bickering about them.

Let’s be honest — we’re all addicted to technology in one form or another — whether TV, Alexa, Nest, or Life Alert® — unless we’re living off the grid. While these new gadgets have had some negative impact, as all innovation does, they’ve done some good too.

Today, I can FaceTime with my grandma in Florida and see her smile each day without boarding an airplane. I can listen to records and watch TV shows without accumulating large quantities of crap in my home. My in-laws can leave me alone and go upstairs and watch Netflix on their iPad while I watch PBS on the overpriced cable I pay for. Should I go on?

No matter the current issue, oldsters have been groaning about younger generations for, well, generations. This concept isn’t new, it’s nature. If I had a dime for every senior I see complaining about millenials, I wouldn’t worry about having Social Security in 40 years.

—Raj Tawney is a journalist specializing in entertainment’s impact on culture

This article is featured in the July/August 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock

20 Hidden Gems in the Criterion Channel

For years, The Criterion Collection — a vast trove of historic and important world cinema — has searched for a streaming home for its film offerings. Once on Hulu, then Filmstruck, it seems the collection has found a permanent place on The Criterion Channel. As a streaming service, it isn’t the simplest platform (launching it with some devices can be tricky or outright incompatible). But if you can manage to set it up, you’ll gain access to a treasure chest of culture. Flipping through the more than 2,000 movies might be a daunting task, so I’m pleased to report that I’ve spent much of the last 10 years bingeing Criterion films to offer a list of good starters and standouts.

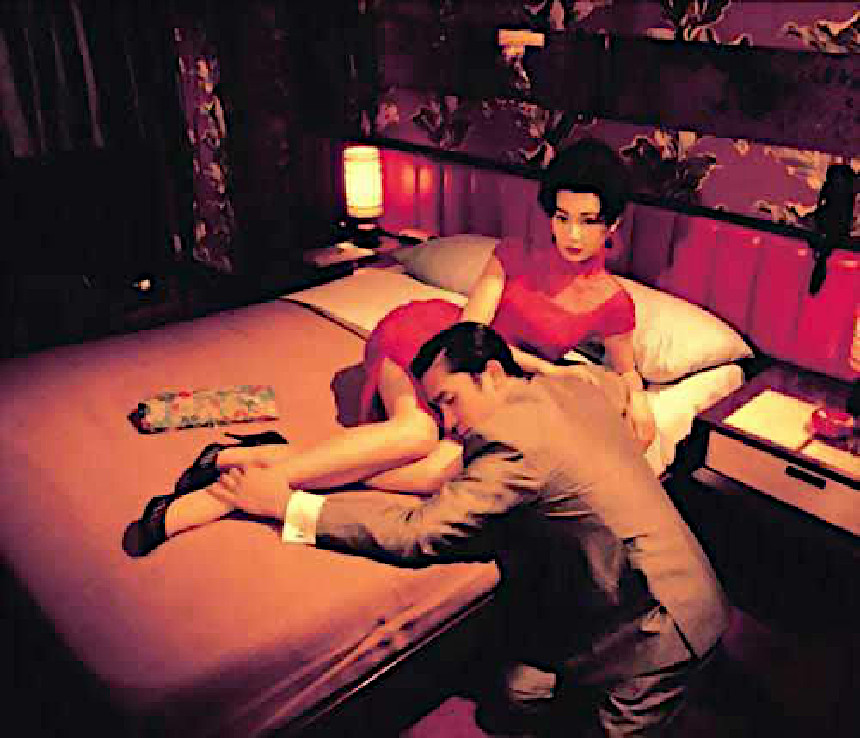

In the Mood for Love (2000)

Guru of kaleidoscopic cinema Wong Kar-Wai’s intimate masterpiece builds romantic suspense through an unlikely bond between two neighboring professionals in 1960s Hong Kong. With elegant, heartbreaking performances and a sensory feast of sight and sound, Wong Kar-Wai has created a tense and sympathetic story that must be experienced.

The Player (1992)

After making his reputation with some big ensemble movies like M*A*S*H and Nashville, Robert Altman made his triumphant return to Hollywood success with this quick-witted satire of the vacuousness of Hollywood itself. It’s devastatingly sharp and funny, and everyone is in it: Burt Reynolds, Whoopi Goldberg, Bruce Willis, James Coburn, Sydney Pollack, Jack Lemmon, Cher. Criterion provides ample extras, like deleted scenes and commentary from Altman himself. By the end, you’ll be working on your elevator pitch for your own screenplay.

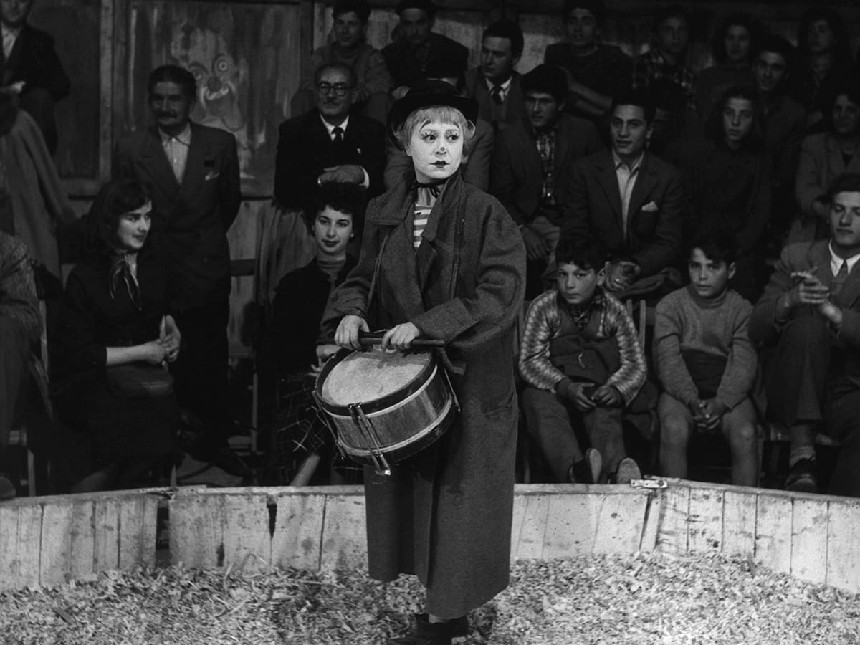

La strada (1954)

Italian cinema dynamo Federico Fellini directs his wife Giulietta Masina in a whimsical and tragic tale of a traveling sideshow performer and his endearing assistant. La strada, or The Road, won the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film and marked the start of Fellini’s signature poetic style. Watch Juliet of the Spirits for a more surreal team-up of Fellini and Masina.

Grey Gardens (1976)

A cult classic documentary on Jackie O.’s reclusive, cat-loving cousins, this portrait of a mother and daughter living in a deteriorating East Hampton mansion offers a rich — and often hilarious — contemplation of the American dream for eccentrics and misfits.

Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! (1990)

For an evening of bonkers, sexy fun, stream a film by Spain’s own Pedro Almodóvar. Antonio Banderas plays a released psychiatric patient who kidnaps a porn star to make her fall in love with him. With a vivid, economical approach to storytelling, the campy auteur inhabits a world of his own, where romance and danger are often puzzlingly intertwined.

White Material (2009)

A white woman in a former French colony in Africa insists on staying with her coffee plantation even as a civil war rages around her in Claire Denis’s unflinching look at colonialism and family bonds. Isabelle Huppert gives an all-in performance, depicting the crazed desperation of a woman fighting for her legacy against forces she can’t understand.

Monsieur Verdoux (1947)

If you’ve never heard Charlie Chaplin’s voice, this uproarious black comedy is the perfect opportunity to witness the Little Tramp in a completely different light: he plays a modern bluebeard, scamming and murdering old women to get by.

Smiles of a Summer Night (1955)

Whether or not he was the greatest filmmaker to have ever lived, Swede Ingmar Bergman was capable of more than heady, molasses-paced existential dramas, as evidenced by this mid-career witty sex comedy. Smiles proved to be Bergman’s first global success and remains the most accessible of his films.

Daughters of the Dust (1991)

Julie Dash made history when she wrote, directed, and produced this fictionalized portrayal of her Gullah heritage. The film was the first from an African-American woman to have theatrical release in the United States. Her raw, intimate portrait of Gullah women at the turn of the century chronicles a transformative time: a group has decided to leave their island home off the coast of South Carolina to live on the mainland, risking the preservation of their culture in search of opportunity.

God’s Country (1985)

French director Louis Malle traveled to the American Midwest in 1979 to document the lives of several inhabitants of Glencoe, Minnesota, and, when he returned, in 1985, economic frustrations and cultural changes had rocked the farming town. The resulting documentary is a candid and honest look at the American “heartland” and its people through the eyes of a foreigner.

Leviathan (2012)

Created by the Sensory Ethnography Lab at Harvard, this experimental documentary — perhaps more-so than any other — makes the viewer feel as though they are actually in it. “It” is a fishing boat off New Bedford, Massachusetts. The extreme closeups and roaming shots are accompanied by hauntingly comprehensive sound engineering that dives underwater and into the daily lives of working men at sea.

Elevator to the Gallows (1958)

A jazzy, twisting thriller, it’s the stunning debut of director Louis Malle and the breakout performance of Jeanne Moreau, who would go on to an unbelievably illustrious career. Elevator set the stage for a new level of expressive film storytelling in France — and elsewhere — depicting two lovers’ unraveling desperation as their murderous plot goes haywire. And they got Miles Davis to improvise the score.

The Exterminating Angel (1962)

Rumor has it that Stephen Sondheim’s next Broadway musical will be a sort of adaptation of Luis Buñuel’s 1962 surrealist dinner party farce. Buñuel, the same director who shocked viewers at the dawn of cinema with his iconic eye-slicing short film Un Chien Andalou, went on to pioneer absurdist filmmaking throughout the 20th century. In Angel, a neverending bourgeois dinner party exposes the inanity and fragility of the upper class.

Foreign Correspondent (1940)

Hitchcock’s second American film, Foreign Correspondent, lost the Best Picture Oscar to Hitchcock’s first American film, Rebecca. The former is a lesser-known rollercoaster of a masterpiece from the master of suspense, following a reporter (Joel McCrea) who stumbles onto an enormous espionage story and finds danger at every turn. Rebecca is also a must-see, but unfortunately it isn’t streaming anywhere currently.

Vivre sa vie (1962)

Most critics would cite Breathless and The 400 Blows as unmissable films of the French New Wave movement (and they’re right), but to take in a unique and utterly watchable expression of the era, go with Godard’s benchmark flick about the tragicomic arc of an aspiring Parisian actress. There’s striking black-and-white cinematography, rock and roll, and a whole lot of smoking.

Claire’s Knee (1970)

The stunning color photography of the French Alps is only the first thing to notice about this deviant and sensual “moral tale.” With its casual, meandering plot of problematic seduction, Claire’s Knee is not for everyone, but smart dialogue and nuanced performances keep it in the French canon.

Walkabout (1971)

Two young British siblings are stranded in the Australian outback and befriend an Aboriginal boy undergoing his traditional rite of passage. This thought-provoking and disorienting film (from the director of the cult family fantasy The Witches) explores adolescence and the brutality of colonialism in Australia.

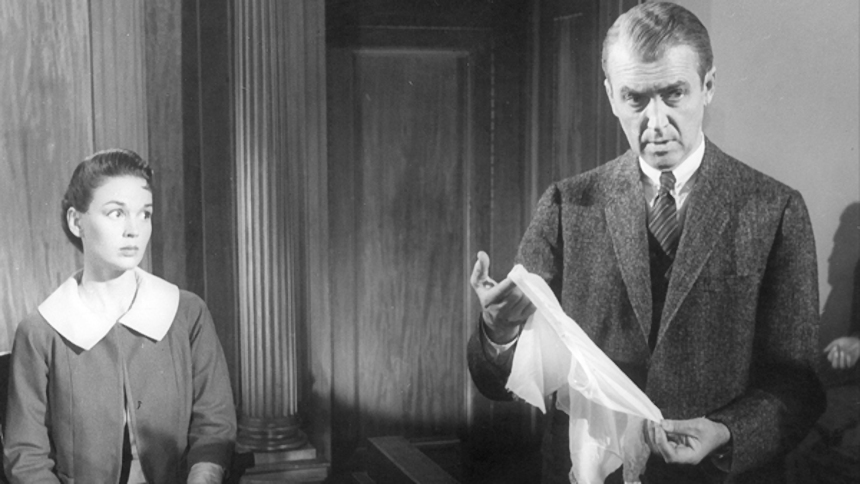

Anatomy of a Murder (1959)

Jimmy Stewart. Otto Preminger. George C. Scott. Duke Ellington. This racy courtroom drama holds up in every way, from its complicated treatment of morality and justice to Preminger’s sophisticated, masterful camerawork.

Throne of Blood (1957)

You could spend hours watching Akira Kurosawa’s films on the Criterion Channel, and there wouldn’t be a second wasted. The Japanese director cemented his status as a visual storytelling icon with films such as Rashomon and Seven Samurai, influencing American westerns, thrillers, and virtually every major director across the globe. In Throne of Blood, Kurosawa tells the story of Macbeth with samurais in feudal Japan, mixing traditional Japanese theatre with a Western classic.

An Elephant Sitting Still (2018)

A sweeping, four-hour journey through the lives of various characters crushed by the weight of life’s disappointments, Hu Bo’s only film was released a few years ago to resounding praise for its brutal honesty and stark realism in depicting working-class Chinese. A difficult, but rewarding, viewing experience, Elephant is a unique, roving ride through people and their problems, offering no easy solutions.

Featured image: Les Films du Losange and The Criterion Collection

13 Virtual Festivals and Events This Summer

Summer is the time for rushing to crowded places to celebrate and experience culture. The best festivals and events in the country should be taking place in the next few months, but gathering hundreds of people together is ill-advised. Instead, lots of organizers have adapted their events to be experienced virtually. On the bright side, this could give even more people access to art, comedy, films, and other cultural events.

Great Smoky Mountains National Park Firefly Light Show

Each summer, the Great Smoky Mountains National Park lights up with 19 species of bioluminescent beetles, also known as fireflies. From late May to mid-June, a particular type of firefly flashes synchronously in the night during its mating season, and visitors flock to the park to witness the stunning display. Although the event was cancelled this year, Discover Life in America created a virtual experience with photographer Radim Schreiber so that anyone can see the natural light show from their own home.

The Pandemic Faire

This virtual art fair curates work from contemporary artists located around the globe for visitors to browse in lieu of attending art festivals in the real world. With new artists added weekly, the Pandemic Faire offers art lovers exposure to new creators along with links to purchase their work from galleries and personal websites.

Second City Online

The Chicago-based improvisational comedy troupe is offering a slew of free virtual programming for you to enjoy “from the discomfort of your own home.” By registering for the live performances with Zoom, attendees can watch and take part in weekly improvisational shows like Improv House Party, Girls Night In, and the family-friendly Really Awesome Improv Show Online. Second City has also released The Last Show Left on Earth, a four-episode YouTube variety show with sketches and musical guests (the first episode features one of the last appearances of the late, great Fred Willard).

All In WA

The first place in the U.S. to be hit hard by COVID-19, Washington state, has seen philanthropists and communities come together to organize a virtual concert to benefit its workers and families who have been hit hardest by the pandemic. All In WA is collecting donations to go toward food and housing insecurity in the state, and the concert, to be livestreamed on June 24, will feature Pearl Jam, Ciara, Macklemore, Dave Matthews, and more.

Blue Ox Music Festival

In Eau Claire, Wisconsin, the Blue Ox Music Festival has brought bluegrass and Americana musicians to this family-friendly event since 2015. Although the festival will lack a live audience this year, the acts will still be livestreamed on YouTube on June 12 and 13. Sam Bush, Pert Near Sandstone, Charlie Parr, and Them Coulee Boys will perform, and Chicago-based bluegrass band The Henhouse Prowlers will give a talk about their experience teaching music in the U.S. and abroad.

Juneteenth

June 19th, the anniversary of the end of slavery in the U.S., is widely celebrated around the country. Denver’s celebration, which includes a music festival, awards, comedy, and financial literacy segments, will be livestreamed on June 18. Their celebration of African-American history also comes with a call to make Juneteenth a national holiday.

Stretching Arms

Through July 31, A Women’s Thing is holding an online exhibition and auction called “Stretching Arms.” The collection features young women artists from New Zealand, Russia, China, and Belarus and asks the question, “How do we transcend solitude?”

Electric Blockaloo

A rave, experienced through the videogame Minecraft, is calling itself “the world’s largest virtual music festival.” With more than 300 electronic artists and digital recreations of music venues and mini-games, admission to Electric Blockaloo on June 25-28 will require “guest list” links from artists distributed via social media.

Seattle Festál

Seattle’s summer (and fall) of cultural festivals will be taken online. The Chinese Culture and Arts Festival, Black Arts Fest, Iranian Festival, and more will offer dancing, art, workshops, and classes to anyone wishing to “make 2020 memorable for the resilience and beautiful moments of humanity,” and you don’t have to be in Seattle to enjoy it all.

CPR Summerfest

Colorado Public Radio’s annual festival of classical music features world-class musicians and singers performing for 10 weeks each summer. This year, CPR is bringing in Joshua Bell, the National Repertory Orchestra, and some of Colorado’s own musical institutions to keep classical selections playing all summer. You can tune in online or by using a smart speaker.

NYC Dance Week Virtual Fest

Dance studios in New York City are offering free dance classes from June 11-20, and they’re open to everyone everywhere. Ballet, yoga, jazz, hip-hop, and tons of other fitness lessons are on offer from a host of studios. If you ever wanted to try a professional class (or 10), this is your chance to do it with no commitment or cost.

Key West Mango Fest

If you were wondering what to do with all of those extra mangoes you have lying around, Key West Mango Fest might have a virtual answer for you. Join in on virtual cooking and cocktail demonstrations, contests, and shopping that revolve around the “king of fruits.”

deadCENTER Film Festival

Oklahoma City’s 20th annual film festival will be going virtual (with some possible drive-in options). By purchasing an all-access pass or individual tickets, you can stream the shorts, music videos, and feature films as well as see panels and workshops with filmmakers from around the globe.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Depending on the Kindness of Strangers: Couchsurfing in New Orleans

We arrived at the Lower Ninth Ward around 11:30 at night. Driving over a drawbridge and through a field where bullfrogs and cicadas broadcast a wall of sound to accompany the thick, humid air, it was tangibly clear that we were 800 miles away from home.

Fourteen years ago, the neighborhood was decimated by flooding caused by a confluence of levee failures that occurred when Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans. Even now, it’s difficult for an out-of-towner to tell exactly where the bayou-adjacent industrial area ends and the neighborhood begins.

When we pulled up to Dustin’s property, it looked familiar from the pictures we’d seen online: a metal-sided house on tall stilts surrounded by a few small cabins and an open air kitchen. My long-time best friend Jill and I looked in from the gate on the sidewalk. Two dogs noticed us and started barking.

One of them was wagging her tail, we observed, but it still seemed risky to enter the gate unaccompanied by their owner. Dustin hadn’t responded to my calls or texts since we’d passed Biloxi. Jill shot me a look of panic that said, We are going to sleep in a bed under a roof tonight, right?

Then, we lucked out. A woman pulled up in a Jeep and let us in the gate. “I don’t live here,” she said, “but I’ll get Nate to show you around.”

Nate told us we were welcome to use anything in the kitchen (coffee, spices, produce saved from nearby grocery store dumpsters), and he showed us the A-frame cabin we would be sleeping in. “Dustin told you we don’t have plumbing, right?”

He hadn’t mentioned it. We’re a low-maintenance pair, though, so an outhouse wasn’t a deal-breaker. Plus, we were crashing with perfect strangers for free.

For the last ten years, I’ve been couchsurfing just about every time I travel. I’ve stayed with (former) strangers in Washington, D.C., Boulder, Nashville, Paris, Ljubljana, and Budapest. They’ve cooked for me, explained local history, given me beer, and even changed my mind on big philosophical questions. I’ve also hosted couchsurfers at my own home and offered all of these things to other travelers. In addition to providing a free method for staying in cities around the world, it has given me a renewed perspective on humanity and our capacity for meaningful association.

Couchsurfing works similarly to a social media site. You create a profile (as a host or a couchsurfer or both) and request to stay with someone. You can scan users’ interests, see what their house looks like, and read reviews of others who have hosted or stayed with them.

When I bring up Couchsurfing to people, their concerns often focus on one possibility: murder. What if someone is only pretending to be a gracious host so that they can have the perfect opportunity to slit my throat while I’m asleep on their hideaway? The truth is that people have been murdered by psychos posing as well-meaning couchsurfing hosts, but it doesn’t happen nearly as often as you might imagine. As Jill and I slept in our humble cabin, we were more worried about mosquitoes, fire ants, or the possibility of a copperhead greeting us first thing in the morning.

As it turned out, we were greeted instead by coffee and a refreshing outdoor shower. The Louisiana sun got hot fast, so we quickly planned an afternoon of visiting St. Louis cemetery (the free one) and grabbing some po’ boy sandwiches. Against some local advice, we also paid a short visit to the French Quarter. What kind of person would visit New Orleans and ignore it? We wandered through the quarter not in search of an “I PUT KETCHUP ON MY KETCHUP” t-shirt, but to day-drink and take in the ubiquitous wrought-iron balconies draped in ferns.

Strolling down Bourbon Street and sipping Paradise Park and Dixie beers, it occurred to us that we hadn’t yet met Dustin, our host. He was working that morning as a pedicab driver, but he assured us he would be home in the afternoon. We resolved to return to the Lower Ninth Ward before hitting Frenchman Street that evening.

When we got back to the property, Dustin was flossing his teeth in the front yard while a few neighborhood kids wrestled with his dogs. He was shirtless, wearing his hair in a messy mullet, and we asked him about the process of building his anarchist paradise. He had come from Austin as a trained carpenter with a camper trailer, and he slept in it while constructing a fence, outhouse, kitchen, shower, two cabins, and — eventually — a house. I hadn’t had the opportunity to utilize the outhouse yet, but of course I was wondering where, exactly, it all went. Dustin explained his rigorous routine for composting human waste, a system I’d only ever read about before. Given the risk for pathogens, it needs to sit much longer in higher heat than other compost. Living this way isn’t unheard of, but surely rare in a metropolitan area.

Who are these people? You might be asking yourself. Nomadic hippies and communist cat ladies? Well, some are, presumably. But the platform is filled with all kinds of people. A common tendency of couchsurfers — besides an interest in world travel — seems to be a desire to live out a reaction against the isolationism of modern living.

In the South of France, I couchsurfed with a chef in his small “sustainability hut” in the foothills of the Alps. We drank rum and played dominos into the night, listening to music from the only source of electricity: a small, solar-powered battery. When it came time to go to bed, he led me into the singular queen-sized air mattress in his cabin that I hadn’t yet considered we would be sharing. I took a side, and he scolded me: “Take off your clothes! They’re dirty!” So, I stripped down to my underwear — regretting my faux pas — and he did the same. We bade each other “goodnight” and slumbered peacefully amid the sounds of the Riviera night.

That might be a radical example of anti-isolationism, but couchsurfing offers subtler ways to break from the privacy of travel and expose yourself to possibilities that would never present themselves otherwise. You can cook a meal with a local, stay in a neighborhood out of the way of hotels and overpriced restaurants, and discover the hidden gems of a city. The irony of couchsurfing is that, as a social media platform, it actually encourages unconditional face-to-face interaction. Although the website hosts a database of user information and geographical algorithms, most of what defines couchsurfing takes place in the real world without any prospect of profit.

In 2009, the year Couchsurfing’s membership hit one million people, a startup in San Francisco launched a similar application called AirBnB. The primary difference between the two websites was that, on AirBnB, hosts could rent out a room or apartment for actual money instead of warm company.

Since then, AirBnB claims it has ballooned to around 150 million users, while Couchsurfing sank to 12 million last year. The wild years of hitchhiking and traipsing around bars with strangers were fun, as I’ve heard from more than a few former couchsurfers, but these days many would rather have a guaranteed place to stay with clean sheets. You can’t blame them. But, still, the omnipresent “sharing economy” seems to lack the soul of its predecessor, the lesser-known, digital “gift economy.” Some experiences can’t be bought, or, at least, not in the same way.

I’ve used AirBnB (once), and it was fine, but it lacks the delicious risk of couchsurfing. Even if an AirBnB’er does meet their host, the interaction lacks the naked humanity and emotional stakes that come with good old benevolence. Don’t you want to meet the person who lets people sleep over just for the heck of it?

According to the website, the values embodied by Couchsurfing are generosity, connection, kindness, etc. So, like Burning Man or Mayberry, the community is predicated on the idea that people are generally “good.” I’m not settled on that conclusion, having witnessed others cheat on their partners, steal booze, and treat people poorly. But I have found that people are endlessly complicated and interesting, and Couchsurfing acts as a fast lane to find that out.

One morning, I went for a jog around the neighborhood. The north end of the ward seemed as though it never recovered from the devastation of Hurricane Katrina. The sidewalks ended erratically, mattresses and old TVs sat junked in the street, and entire blocks of housing lots sat empty, growing dense flora around old foundations.

Jogging south, the neighborhood perked up considerably. Colorful, modern homes with dramatic, jagged angles lined the streets as though they had risen from the earth after the floods receded. One of these houses, just a block and a half away from Dustin’s house, was posted on AirBnB for $195 a night. If I wasn’t committed to a spontaneous lifestyle of radical trust in strangers, I could have paid for more reliable lodgings on the same street — plus air conditioning, indoor bathing and cooking, and Wi-Fi. But where’s the fun in that?

Featured image by Jill Young, edited by Amy Tackitt

Some names have been changed.

The First Virtual Reality

Our desire to fully immerse ourselves into another world has given way to strides both spectacular and peculiar in the realm of virtual reality.

In 1981, John Waters’s film Polyester was shown in theaters accompanied by scratch-and-sniff cards that included scents like model airplane glue, roses, and dirty shoes to give the audience a more complete sensory experience of his regressive cinema. In 2016, an episode of the eerie tech-drama Black Mirror depicted two lovers shedding their physical selves and uploading their consciousnesses permanently into a digital simulation of a 1987 beach town.

At the dawn of virtual reality, a multi-sensory experience was presented as a means for teaching, if nothing else.

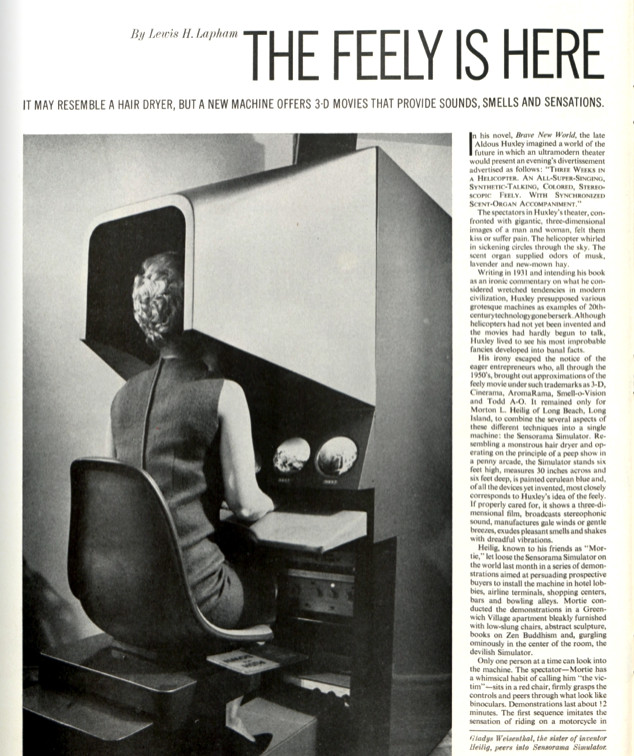

“A basic concept in teaching is that a person will have a greater efficiency of learning if he can actually experience a situation as compared with merely reading about it or listening to a lecture.” That was the reasoning that Morton Heilig gave for inventing the Sensorama Simulator in 1962. His machine resembled a hair dryer from a space age salon, but it was actually an early incarnation of virtual reality technology. After an initial buzz of excitement around Heilig’s invention, the world promptly forgot about him and his innovations.

Heilig’s prototype showed movies that mostly adhered to his instructional vision for the Sensorama, but he needed to make it sexy, too. Literally. One video that he showed in demonstrations featured an exotic belly dancer performing an intimate dance for the viewer. As the spectator watched the three-dimensional video, perfume wafted from the Sensorama any time the dancer gyrated close to the camera. Another video showed a high-speed motorcycle ride through the streets of New York City, complete with wind and diesel smells. Although it wasn’t necessarily functional at training anyone to be a motorcyclist, the experience succeeded at freaking people out.

In 1964, this magazine covered Heilig’s invention, comparing it to the “feely” theater of Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. The term “virtual reality” would not have been recognizable at the time, so the mysterious futurism of Huxley’s dystopian novel had to suffice to impart the peculiarity of the Sensorama Simulator to Post readers. “Resembling a monstrous hair dryer and operating on the principle of a peep show in a penny arcade, the Simulator stands six feet high, measures 30 inches across and six feet deep, is painted cerulean blue and, of all the devices yet invented, most closely corresponds to Huxley’s idea of the feely,” Lewis Lapham wrote.

The possibilities for the invention, from Heilig’s perspective, were endless. It could be used to train pilots, sell beach vacations, test drive new cars, or just sit at an amusement park, collecting quarters. At the time of the Post’s report, Heilig had attracted the attention of an investor who gave him the ears of executives and entertainment insiders. His Sensorama made it into Universal Studios, Santa Monica pier, and Times Square as an attraction. “3-D, Wide Vision, Stereo Sound, Aromas, Wind, Vibrations” the machine advertised on its front. Thousands of people must have sat in the bucket seat and felt the simulated wind of the Sensorama during its nationwide tour. Unfortunately, the money from a big-time investor never came, and Heilig’s sensory vending machine became a lost oddity.

In 1984, Heilig was interviewed with his invention, and he described the Sensorama’s capabilities proudly, saying, “this was 30 years ago, and now today, there still is nothing as complete as this.” Before Heilig died, in 1997, moves toward virtual reality began to take place, with gaming companies like Sega and Nintendo beginning to release VR systems. Then, “4-D” movies became hit attractions at parks like Six Flags and Disney World. Shows like “Honey, I Shrunk the Audience” and “It’s Tough to Be a Bug!” combined three-dimensional video with animatronics, scents, winds, and other effects to wow audiences and terrify children.

Heilig had worked as a consultant with Disney, supposedly sparking the company’s interest in 3-D video. The technology has been used mostly (even in its 4-D incarnations) to incite thrills and chills, but Heilig had always hoped for more. Speaking to Lewis Lapham for the Post in 1964, Heilig said, “It’s an empathy machine, and if we can develop it right, maybe we can get it to inject feelings of warmth and love.”

These kinds of ambitious results for his high hopes for virtual reality remain to be seen (or smelled).

Featured Image: I.C. Rapoport, 1964

Declutter Your Digital Life in 5 Steps

Much ado has been made over clearing the clutter in our kitchens and closets, but physical spaces aren’t the only ones we neglect. A scattered situation on your computer and smartphone can put a damper on your productivity (and sanity).

If you’re the type of person who spends far too long tracking down files and emails and even longer getting lost in the chaos of possibilities on your screen, behold some tips for taking a minimalist approach with your digital spaces.

Step 1: Tame Your Subscriptions

Over the years, you’ve likely gotten yourself onto an e-mail newsletter list or two… or 341. Luckily, this is easily managed using one of a few different options. The first, and most controversial, is Unroll.me, a service that allows you to take a look at all of your e-mail subscriptions and quickly unsubscribe as you please. Like many free and easy internet services, Unroll.me collects and sells your data. If that makes you uneasy, try the open source Google Script, Gmail Unsubscribe. It works with your Google Drive to build a list of subscriptions for you to manage (without selling your receipts to Uber).

Use caution when unsubscribing from e-mails and newsletters manually. If you don’t recognize the sender, mark it as spam instead of clicking any hyperlinks.

Step 2: Shape Up Your Inbox

Take this resounding advice from professionals everywhere: do not let your e-mail inbox dictate your to-do list. Darla DeMorrow is a Certified Professional Organizer with HeartWork Organizing, and she instructs clients to get into the habit of ruthlessly deleting e-mails. “In the end, always ask yourself, what is the worst that can happen if you accidentally delete an email?” she writes. “For most of us, the answer is: absolutely nothing.”

DeMorrow recommends filing all of your e-mails into a folder “Prior to (current date),” then deleting the folder after a time you specify. The idea is that anything truly important will have been accessed and pulled out by you in that time. Otherwise, you probably don’t need it. Some other good e-mailing habits:

- Don’t store photos and documents in e-mails (or text messages). If you’ll need an attachment, save it and file it immediately.

- Utilize folders, so you can compartmentalize newsletters and subscriptions that you do want from the more urgent stuff.

- Make the delete button your default reaction. If you need, you can grab e-mails out of your trash folder afterwards (as long as you set it to empty out at proper intervals), but this practice will keep your inbox much more manageable.

Step 3: Trim Your Documents and Apps

Do you use folders? Do you use folders in your folders? Whatever your approach, the important thing is that your files have a home. If you’re serious about decluttering your computer, the first thing you can do is delete temporary files — those that your computer creates by running programs. It’s easily done (on PC) by running Disk Clean-Up from the Control Panel. For Macs, Techlicious recommends starting with Disk Utility > First Aid > Repair, then finding a Mac cleaner app like CleanMyMac X.

Next, you’re ready to tackle those folders. Your downloads folder is a likely crevice for all kinds of things to fall into (hopefully you don’t have files on your desktop, but start there if you do). Sort the files by type, and move them all to the documents folder, creating folders and subfolders as needed for the different types of files you have. You don’t need to strictly follow the organization that your computer already provides; the key is to create a system that helps you to quickly find and use the files you need. Luis Perez, a San Francisco-based organizing expert, recommends setting aside time at the end of each month to keep up with your files. Ten or 20 minutes here and there can save hours down the road.

To get control of your program and application situation, look inward. Think about the apps you actually use, not the ones that “might be useful someday.” Apps (on computers and smartphones) are a big culprit of memory and data usage, and they can slow down the performance of your device a great deal. Delete liberally anything that isn’t a must-have. If you find yourself wanting to download it again someday, so be it, but at least you’ve given it that test.

Step 4: Sort Photos, Once and for All

DeMorrow, from HeartWork, says that photos are the first thing people ask about with regard to digital organizing. With so many pictures in so many places, it can seem like a daunting task to get them together. But, as DeMorrow says, you need to “decide to decide to move forward.”

Get all of your physical photos together to see what you have. “Once you see what you have,” DeMorrow says, “you can reduce any duplicates, release low-quality photos, empty photo albums and frames, and other trash that was stashed in with your photos. Then decide whether you want to reset those physical assets in photo-safe storage boxes or digitize those precious photos.” Scan all of your pictures — or pay someone else to do it — and gather them with pictures from your phone, USB drives, memory cards, and maybe even some old floppy disks. From here, you can create folders to organize them by year, event, vacation, etc. Of course, you’ll want to back them up using a cloud service, so that you don’t risk losing your memories to a computer crash.

Step 5: Better Your Browsing

Managing the storage of your digital information is a great habit, but the ways you interact with your devices each day can be damaging to your workflow. One habit you can start today is simple: close those tabs. We’ve all been in the delusional mindset that we will eventually get around to reading that 10,000-word thinkpiece that we’ve opened as yet another tab on our browser during an already-bustling workday. Experts say that we cannot multitask, even if we think we can, and having various tabs, windows, and programs running nonstop could be hindering your ability to focus on and complete a single task. As a habit, it can damage your career. Here are some tips for a minimalist approach to using your devices:

- Keep two to three browser tabs (or less!) going at a time. Your productivity likely will not benefit from more, and you will lose the temptation overstimulate your brain.

- Close all of your windows at the end of each day. When you come in the next morning, you can start anew with fresh tabs.

- Base your workflow on an actual to-do list, not a visual representation of 20 slivers of tabs running across your screen.

Now, forget about the mop and bucket, and get to work on your real spring cleaning.

Featured image: Wikimedia Commons, by Wikissed via the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Introverts, Unite! The Rise of the Hermit Economy

“There’s a great, big beautiful tomorrow… shining at the end of every day!” sings the animatronic family of Walt Disney’s “Carousel of Progress.” The rotating robot stage show premiered alongside “It’s a Small World” at the 1964 New York World’s Fair. Audience members ride around scenes depicting an American family in four eras of technological innovation, and the ride culminates in the future in an electric home that affords its inhabitants leisure by performing their time-consuming chores.

Dr. Larry Rosen remembers visiting “Progressland,” the original name of the General Electric-commissioned ride, at the World’s Fair in 1964. Rosen remembers that, ironically, the visionary experience offered an optimistic glimpse of a future in which innovation would free up our time for more socialization. “The intention was always that it would do the menial tasks we didn’t need to do,” he says, “but who knew the menial tasks would be connection and communication?”

Rosen is a professor of psychology at California State University, Dominguez Hills and co-author of The Distracted Mind: Ancient Brains in a High-Tech World. He says we’ve reached a point where technology is making hermitry — not human interaction — easier.

In a way, Progressland’s promise of convenience technology has come to fruition. With even the slightest smartphone savvy, you can hire out all of your pesky chores: shopping for groceries, walking the dog, washing the car, assembling furniture, waiting in line at the DMV. Running errands could become a thing of the past, for some, if current trends keep up, leaving us with tons of time for… what, exactly?

Picture it: you wake up and cook your breakfast from groceries delivered via an app like Instacart or Shipt before settling down for a long workday-from-home — as 115% more Americans have been doing since 2005. Then, a stylist — from an app like Glamsquad — makes a house call to give you a blowout and a manicure while Booster is gassing up your Subaru outside. Now you’re finally ready… to binge on an entire season of a Netflix drama and settle in with some sushi delivery — ordered through your Seamless app, of course.

“These kinds of services drive us away from face-to-face interactions,” Dr. Rosen says. “If you’re spending four to six hours each day on your phone (as we’re finding that people are) making short connections that aren’t real relationships or meaningful connections, you might be much more prone to stay inside.”

According to surveys from Rockbridge Associates, the on-demand economy grew 58 percent in 2017, with sectors like housing and food delivery more than doubling. All of these on-demand startups are marketed to ease the burdens of our busy lives, but convenience technology seems to be giving us little reason to leave the house. A sort of “hermit economy” has taken shape for those who can afford it.

Dr. Damian Sendler, a digital epidemiologist with Felnett Health Research Foundation, says the hermit economy could have long-term consequences in terms of social interaction. “Once you begin relying on this nonverbal communication of sending orders on your phone, you forget how to interact with other people,” he says. “When you do have to deal with customer service or go somewhere to get something done, you might develop anxiety and a fear of interacting with people.”

The chicken-or-the-egg question is relevant here: does increasing “APPization” of services cause reclusiveness or is it welcome technology for those already desiring a more cloistered existence?

Americans have displayed introverted behavior, at least to some extent, for centuries. Reclusiveness in America has inspirational legacy — as in Henry David Thoreau’s Walden — as well as tones of pathology and domestic terrorism in the case of Ted Kaczynski. Lately, self-proclaimed introverts have been declaring the virtues of holing up at home for their health, with scads of online articles offering “signs you might be an introvert” and an introvert Facebook page with 2.5 million followers declaring relatable maxims like “Sometimes I stay inside for an entire weekend and I regret nothing.”

Popular psychology presents introversion as the perfectly natural state of being “drained by social encounters and energized by solitary, often creative pursuits.” Instead of the conventional opinion to advise socialization at every turn, a lot has been made of the need for societal accommodation for introverts, particularly in education and the workplace.

Andrew Becks, a 33-year-old digital advertising C.O.O. from Nashville and self-proclaimed introvert, says he is emotionally drained after an entire day of being “on.” Becks says, “The last thing I want to do is interact with people sometimes. I’m a lot less stressed when I feel I can use my evenings as a kind of detox from socialization.”

Becks admittedly utilizes convenience technology often. He and his husband used the app TAKL in their recent home renovation. The platform allows users to post a job and receive proposals and prices from vendors, mostly through text interactions. He’s been a fan of online food ordering ever since it came around about a decade ago. A typical night in with friends entails getting some drinks, ordering food delivery — from the vast selection of online options — and watching TV or a movie.

“The idea of going to a nightclub or a bar just does not appeal to me, but that we can leverage technology to have people over and do more than just order a pizza is pretty cool,” he says. “It allows people to maintain friendships with like-minded people in environments that are more comfortable for them.”

Becks likes the increased accountability that comes with online ordering, and he doesn’t mind losing some human interaction day to day. In fact, he says it helps him to appreciate it more, and to be more receptive to it, when he does have meaningful connections with people.

He admits that there are drawbacks to this kind of encompassing technology though. With so many opportunities for cyber consumerism, the Nashville millennial says you could get stuck in a virtual rabbit hole where you’re beholden to an algorithm to present all of this information to you: “It helps the company’s revenue and it creates a personalized experience, but it’s a kind of vortex where the brands people interact with are controlling the experience on a scale we’ve never seen before. It’s helpful to remember that we’re interacting in an ecosystem that’s designed to extract as much money out of us as possible.”

A bump in at-home services could be a sign of the market fulfilling a need, but the line between healthy solitude and socially anxious hiding can be a fuzzy one.

In Japan, the latter has been observed as a widespread trend called hikikomori. In the last decade or so, more than half a million Japanese people, ages 15-39, have been observed to live drastically reclusive lives, spending most or all of their time in a bedroom. The hikikomori, mostly men, are thought to be traumatized by social pressures, abuse, or failure, so they have resigned themselves to a life of lying around, reading, and browsing the internet indefinitely. A leading researcher of the phenomenon said global changes in social life and family are behind hikikomori, a condition that looks a lot like an exacerbated case of Social Anxiety Disorder.

Social phobia is linked to high-income countries, according to the World Mental Health Survey Initiative. The survey found that these countries (like the U.S. and Belgium) face prevalence of Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD) at rates more than three times higher than low-income countries (like Iraq or Ukraine). The United States has the highest rate of people who have experienced SAD at some point in their life at 12.1 percent, and that number is up from 5 percent in 2002.

It would be difficult to deny the connection of the rise in reported social anxiety to fundamental changes in daily communication via tech use. How the creeping transformation of the service economy enters into it is up for discussion. Dr. Sendler says aspects of the gig economy can create a superficial, unequal division of power between convenience-seekers and service providers that divides communities: “From a mental health perspective, what we see is an escalated division between people and the social problem of actually connecting with people with boundaries that we didn’t have before.”

Dr. Rosen says technology is embedded in culture, and, while an influx of digital services can create an environment for isolation, it ultimately comes down to our own willingness to salvage a tradition of community in the face of a reclusive future. “Part of going outside is that there’s always a chance to have an interaction, but many people avoid these opportunities,” Rosen says. “Social anxiety is part of a larger anxiety constellation” that he says is ubiquitous.

There is precedent for such public health interventions. Campaigns against tobacco use and bullying, as well as ones for wearing seatbelts, have shown positive results. It is likely trickier, however, to meaningfully advocate for something as nebulous as quality human interaction.

The Carousel of Progress still spins Disney visitors through its idealistic portrayal of American innovation each day. It even proclaims to be the longest-running stage show in America despite the lack of actual human beings onstage (perhaps an apt undertone for futurism). The attraction hasn’t undergone any major changes since 1994, so it currently exists in the name of nostalgia. An android family forever singing in unison about “the great, big beautiful tomorrow” increasingly feels like wishful thinking from another time.

8 Healthier Tech Habits You Can Start Today

Each year, more studies are published confirming our reluctant suspicions that smartphone addiction is pervasive and damaging. Even when our phones aren’t going off, we still feel the vibrating rings in a condition called “phantom vibrations.” Receiving a constant feed of texts and notifications is so common that we’re developing separation anxiety… for smartphones.

Our favorite and most convenient tech tools seem to have turned on us, but the antidote doesn’t have to be an absolute purge of screens. Introducing some moderation to your (and your family’s) tech consumption can steer you toward more meaningful relationships and fewer phantom vibrations.

1. Refrain from checking your phone in the morning

Starting your day doesn’t have to be a recap of everything you missed online while you were asleep. Forego the morning notifications and e-mails, and use the time to make your own tech-free routine. Google design ethicist Tristan Harris writes that instead of framing our morning around a menu of missed online experiences, we should frame it around our actual needs. Brew coffee. Eat a balanced breakfast for once. Walk the cat.

2. Leave your phone at home once a week

An attachment to smartphones is often the result of underlying “FOMO,” or fear of missing out, according to Dr. Elizabeth Cohen, a cognitive behavioral therapist based in New York City. She recommends leaving your phone at home at least one day each week in order to be more present (even if it’s only for a day). The fear of missing out often stems from feelings of inadequacy, Cohen says, and “the more someone can become aware of their underlying fear the less likely they will have the same deep need for the phone.” If ditching your device for a whole day is too overwhelming, start smaller. Leave it behind while running errands or taking lunch.

3. Keep moving

An unfortunate side effect of staring at screens is that it can promote sedentary behavior. Committing to taking tech breaks and moving around in between scrolling and posting can reduce stress and help to make interactions with technology more meaningful. Chiropractor Dr. Steven Shoshany warns against “text neck,” pain and soreness in the upper back, shoulders, and neck that can ail anyone who tilts their head down too often to view a screen. Besides taking breaks from screen-gazing, Dr. Shoshany recommends holding your phone at eye level as often as possible. He says to spend one whole day being mindful of your posture and how your interaction with tech affects it: “Any prolonged period when your head is looking down is a time when you are putting excessive strain on your neck.”

4. Talk more and text less

Face-to-face communication is preferable, but even phone and video calling have proven to be more meaningful forms of interpersonal connection than messaging. At a time when young people face anxiety over live interactions and scores of us have “friends” we might never meet, it’s more crucial than ever to start talking to each other. Sure, there are times when a short text will suffice, but if you find you’re typing it out more often than not you should make an effort to reacquaint yourself with the faces and voices of your friends and family.

5. Make family dinners phone-free

The importance of daily (or near-daily) family dinners for healthy adolescent development has been well-documented. Clinical psychologist Dr. Beatrice Tauber Prior says that having tech-free family dinners strengthens bonds and gives children security in knowing time is set aside for problem-solving and conversation. For families looking to cut down on screen use, dinnertime is the perfect place to start.

6. Observe the 20-20 rule

Many people find that their job requires staring at screens daily, but there are still healthy habits you can practice to give your body a break. Dr. Alex Tauberg, a chiropractor from Pittsburgh, recommends the 20-20 rule: for every 20 minutes you find yourself staring at a screen, take a break and walk around for at least 20 seconds to help prevent postural strain. Many optometrists also tout the 20-20-20 rule to save your eyes: after 20 minutes with a screen, look at something 20 feet away for 20 seconds. Limiting screen time to 20 minutes at a time can also help to set boundaries on your browsing and help you manage your time.

7. Start journaling… on paper

Do you remember what your handwriting looks like? Gathering your thoughts in a journal might seem a quaint method for self-reflection, but it’s the perfect antithesis to the wild stimulation of the internet. No pop-up ads, newsletters, or messages from friends can distract you while you’re writing, and you’ll discover how liberating it can be to practice expressive writing that isn’t tailored for shares and likes.

8. Don’t sleep with your phone

It’s time to buy a real alarm clock. Keeping your phone next to you in bed lessens the quality and quantity of your sleep, especially if you check it intermittently (and you probably do). This is especially true for adolescents: they need the sleep and will almost certainly be on any screens within arms-reach. Not only does the stimulation of answering e-mails and crushing candies in bed keep your mind active, but the blue light from your phone or laptop actually tricks you into “daytime mode” and disrupts your sleep by suppressing your production of melatonin. If you must cuddle with your device each night, using an app like f.lux or Night Shift (or using a night mode on some devices) reduces your exposure to blue light.