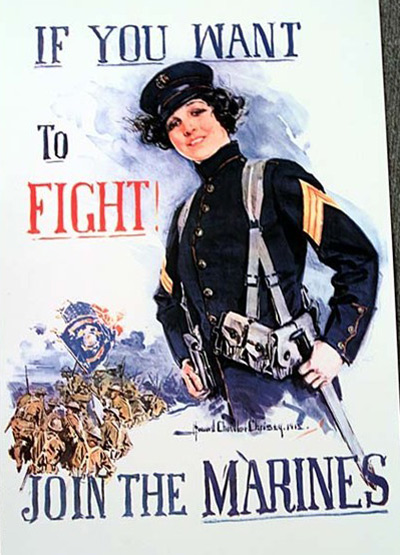

Trailblazer Opha May Johnson Becomes the First Female Marine

It’s been said that history is made by those who show up. Last week,The New York Times ran a story on First Lieuntenant Marina A. Hierl; Hierl is one of only two women to pass the Marine Corps Infantry Officer Course. Lieutenant Hierl made further history as she was assigned her own platoon to lead. Hierl is one of the people that shows up. Opha May Johnson led the way for women like Lieutenant Hierl and proved that you can make history by showing up first. 100 years ago today, Johnson earned the distinction of becoming the first woman to enlist in the United States Marine Corps.

Born Opha May Jacob in Kokomo, Indiana in 1879, the future Marine attended Wood’s Commercial College. She earned the rank of salutatorian, graduating from the shorthand and typewriting department in 1895. Three years later, she married Victor Johnson, musical director of the Lafayette Square Opera House in Washington D.C.

According to the Richmond Time-Dispatch dated September 1, 1918, Johnson was already a civil servant, working for the Interstate Commerce Department, when the chance came up for her to apply to the United States Marine Corps Reserve. The reserve had been established in 1916, concurrent with the U.S.’s involvement in World War I. During the last two years of the war, women were allowed to join branches and reserves to cover responsibilities typically held by men that were under active deployment; 33,000 women would eventually serve support staff.

On that day in 1918, Opha May Johnson found herself at the front of the line. Private Johnson became the first of over 300 women that would enlist in the Marine Corps during the remainder of World War I. Her first assignment sent her to Marine Corps headquarters; she worked there as clerk where she managed the records of the other new, female Marines. After the conclusion of World War I in November, 1918, the various branches of the service began discharging all women from active duty. Johnson took a job as a clerk in the War Department (which would be renamed as the Department of Defense in 1949).

Johnson died on August 11, 1955, at Mount Alto Veteran’s Hospital in Washington, D.C. Her funeral services coincidentally fell on August 13, 37 years to the day after she enlisted. She is buried in an unmarked grave in Rock Creek Cemetery in D.C. Last year, the Women Marines Association began to fund-raise to install an official marker; the successful project will result in a site unveiling on August 29, with the Commandant of the Marine Corps, General Robert B. Neller, scheduled to speak.

Since Johnson’s historic enlistment, thousands of women have served in the U.S. Armed Forces in combat and support capacities. As of 2015, around 2 million veterans in the U.S. were women. Johnson helped pave the way for later Marines like Bea Arthur; before becoming the actress best known for Maude and The Golden Girls, Arthur drove a truck as a member of the Women’s Reserve and attained the rank of staff sergeant during her stateside service in World War II. The late Margaret Brewer, the first female Marine to be made a general, was promoted to brigadier general in 1979. As of May 2018, 92 women serve in combat positions in the USMC; approximately 7% of the 186,000 active Marines are women.

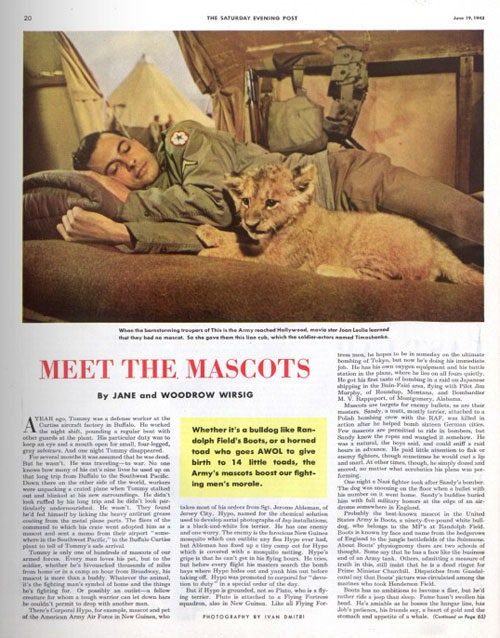

75 Years Ago: Meet the World War II Mascots

The news coming out of World War II was often grim, but every once in a while, The Saturday Evening Post found a way to lighten the mood. This article from our June 19, 1943, issue shared the stories of animal mascots that were keeping soldiers company during the war. From Randolph Field’s bulldog, Boots, to the Las Vegas Army Gunnery School’s horned toad, Machine-Gun Pete (later renamed Petricia after some toad babies showed up), these companions found themselves stowing away on transports, jumping out of planes, and even occasionally earning a military promotion. Many of them (mostly dogs) brought the soldiers moments of joy and levity, and maybe something more. As the authors write, “Whatever the animal, it’s the fighting man’s symbol of home and the things he’s fighting for.”

Considering History: Remembering World War II Heroism Beyond D-Day

This column by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

The June 6, 1944, Allied landing on France’s Normandy Beach—the operation that came to be known as D-Day—was one of the most ambitious military operations ever undertaken, and featured countless stories of striking bravery and heroism. To cite just one example from my home state, Virginia’s state highway 29 has been officially designated the “29th Infantry Division Memorial Highway,” in honor of a unit based out of the state’s Fort Belvoir that served in the vanguard at Normandy, suffered tremendous casualties as a result, and then helped lead the subsequent advance through France and into Germany that produced the final Allied victory over the Nazis.

No doubt because of such remarkable stories, as well as the invasion’s central importance to the war effort, D-Day has figured prominently in our national collective memories of the war. From early cultural portrayals like the blockbuster films D-Day: The Sixth of June (1956) and The Longest Day (1962) to more recent ones such as the bravura opening sequence of Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan (1998) and the acclaimed HBO miniseries Band of Brothers (2001), popular culture has returned to the histories of D-Day and its aftermath time and again.

Those histories, and most especially all those Allied servicemen who took part in them, are certainly well worth commemorating, and the operation’s anniversary provides an opportunity to do so once more. Yet there are many other World War II feats of heroism that extend beyond the Normandy invasion, including a number featuring soldiers of color who (because of the military’s segregated status) were not allowed to take part in the D-Day operation. Adding them to our commemorations deepens our perspective on what every American community contributed to the cause.

Thanks to director John Woo’s historical film Windtalkers (2002), the stories of the World War II Navajo code talkers — stories that were classified until 1968 and largely unremembered until at least the 1980s — have perhaps begun to enter our collective memories, but nonetheless deserve a far fuller presence in our histories of the war. Recruited in 1941 and 1942 by Philip Johnston, a World War I veteran who had grown up on a Navajo reservation and spoke the language, these Navajo soldiers —some as young as 15 or 16 years old — proved vital to the Allied efforts, especially in the war’s Pacific Theater. Major Howard Connor, a signal officer who served with the 5th Marine Division at the crucial 1945 Battle of Iwo Jima, later argued that, “Were it not for the Navajos, the Marines would never have taken Iwo Jima.”

African American servicemen likewise contributed mightily to the Allied efforts. Despite their absence from combat roles in — and thus most cultural representations of — the Normandy invasion, African American soldiers such as those in the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion did indeed take part in the D-Day operation. And both before and after June , 1944, African American units played vital roles in combat operations throughout the war. The Tuskegee Airmen, also known as the Red Tails (the title of a 2012 historical film about the unit that deserves wider viewership), flew tens of thousands of missions in North Africa, Italy, and beyond. The 761st Tank Battalion, also known as the Black Panthers, saw extensive combat under General George Patton in the post-Normandy Battle of the Bulge, among many other European operations, and have been called “one of the most effective tank battalions in World War II.”

Native Americans and African Americans have played significant roles in every American military conflict from the Revolution on, and these World War II servicemen extended and amplified those profoundly impressive histories. But perhaps the most inspiring and heroic World War II American servicemen of color were the Japanese American soldiers who quite literally volunteered from within the exclusionary internment camps and helped change the course of the war.

In early 1943, roughly a year after President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 had created the internment policy, the administration reversed its concurrent policy prohibiting Japanese Americans from serving in the armed forces. The move was both a practical and a cynical one, both a response to wartime needs and an attempt to counter Japanese propaganda about the camps, and it would have been understandable if Japanese Americans had refused to serve the nation that had defined them as “alien enemies.” But their response was instead literally and figuratively overwhelming: in Hawaii, an initial call for 1500 volunteers led 10,000 Japanese Americans to recruiting offices; while more than 2000 volunteered in that initial surge from within internment camps.

By the war’s end, more than 33,000 Japanese Americans had served in two segregated units, the 442nd Infantry Regimental Combat Team and the 100th Infantry Battalion. The 100th, the first unit to see combat in 1943 (initially in Italy and then throughout Europe), came to be known as the “Purple Heart Battalion,” as it took nearly 10,000 casualties by war’s end. And Commanding General George Marshall said of the 442nd, who fought under his command throughout the pivotal post-Normandy campaigns in 1944, that “They were superb! They showed rare courage and tremendous fighting spirit. Everybody wanted them.”

D-Day was a crucial wartime operation, but it has become a great deal more than that. It rightly serves as an occasion through which to remember the service, bravery, and heroism of American World War II servicemen and veterans. Adding the stories of the Navajo code talkers, the war’s African American units, and the Japanese American soldiers of the 442nd and 100th to our national collective memories not only amplifies those commemorations of heroism, but makes clear how much every American community share

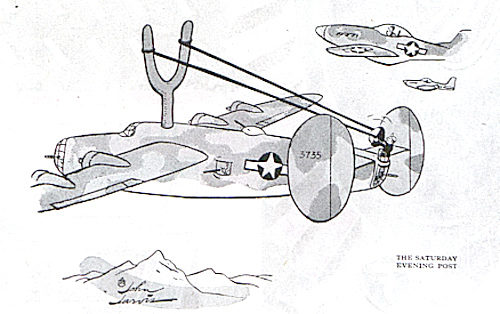

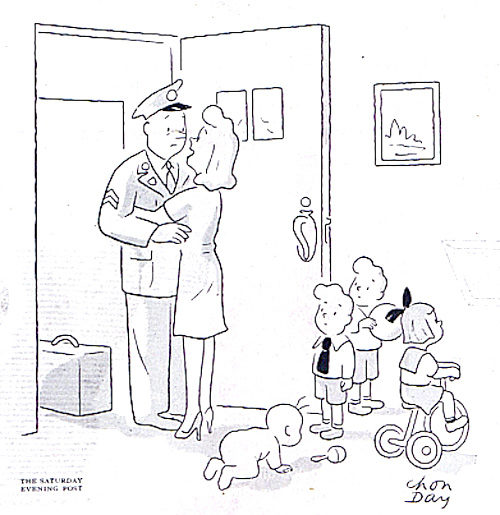

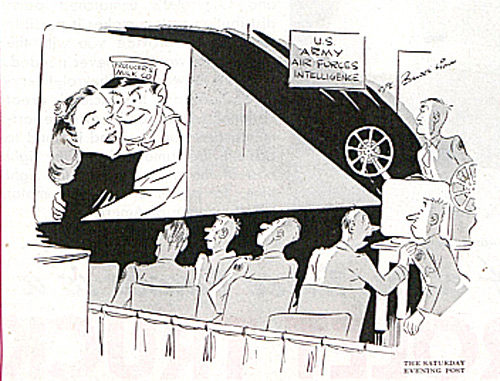

Cartoons: The Spirited Soldiers of World War II

In the 1940s, The Saturday Evening Post did its best to cheer people up amidst the grim reports from the war. These cartoons gave readers a brief respite from their worries.

May 19, 1945

John Jarvis

April 4, 1945

Chon Day

July 21, 1945

July 7, 1945

June 30, 1945

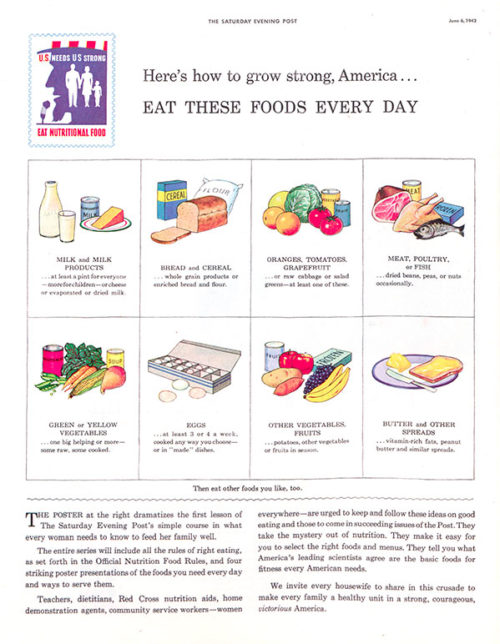

A Course in Nutrition, circa World War II

Build-your-own World War II menu with nutrition basics from 1941.

—

U.S. Needs Us Strong

-Originally published in The Saturday Evening Post, June 1941-

As our part in helping to make America strong, The Saturday Evening Post presents a simple, basic course in nutrition, based on the findings of our Government’s National Nutrition Committee.

Here’s How to Grow Strong, America … Eat These Foods Every Day

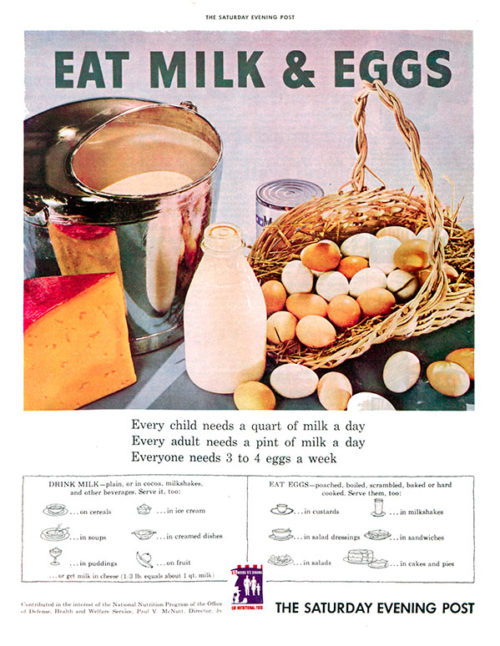

Eat Milk and Eggs

- Every child needs a quart of milk a day.

- Every adult needs a pint of milk a day.

- Everyone needs 3 to 4 eggs a week.

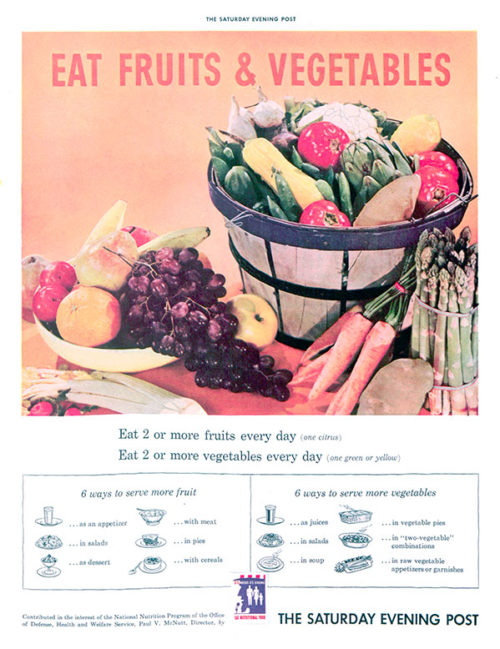

Eat Fruits & Vegetables

- Eat 2 or more fruits every day (1 citrus).

- Eat 2 or more vegetables every day (1 green or yellow).

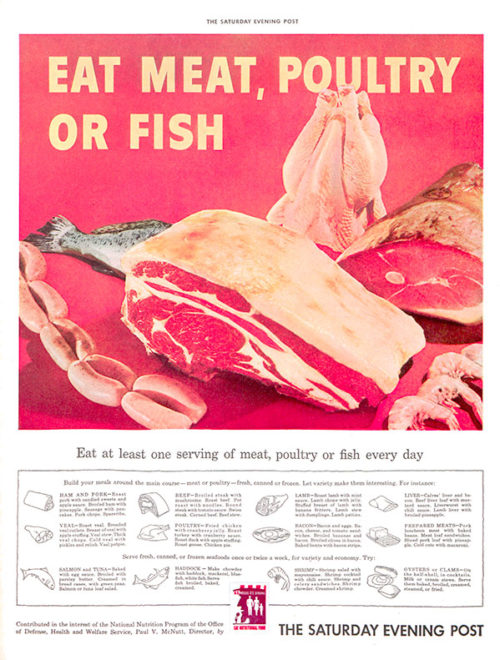

Eat Meat, Poultry, or Fish

- Eat at least 1 serving of meat poultry or fish every day.

- Build your meals around the main course — meat or poultry — fresh, canned, or frozen.

- Serve fresh, canned, or frozen seafoods once or twice a week, for variety and economy.

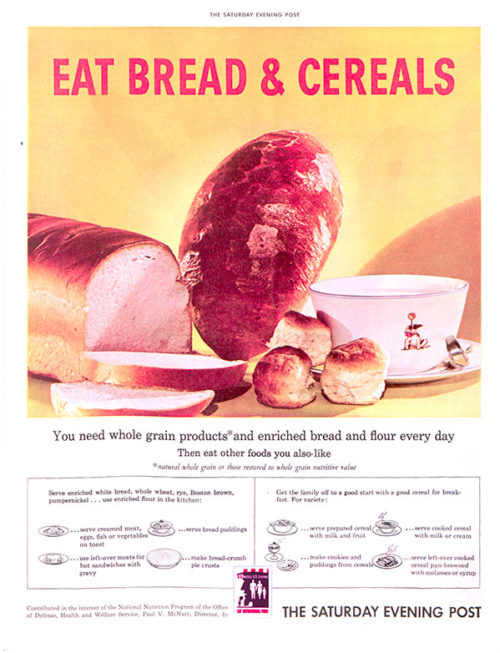

Eat Bread & Cereals

- You need whole-grain products (natural whole grain or those restored to whole grain nutritive value) and enriched bread and flour every day. Then eat other foods you also like.

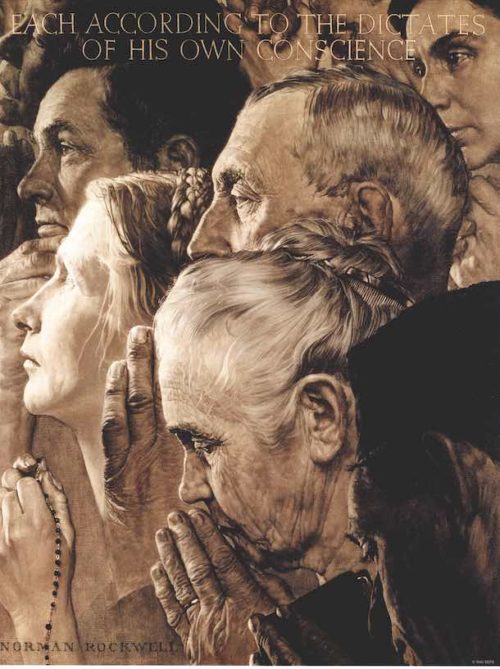

Will Durant’s ‘Freedom of Worship’

In 1943, the Post commissioned four writers to craft an essay to accompany each of Norman Rockwell’s Four Freedoms paintings, which had quickly come to represent America’s moral imperative during World War II. You can read the other three essays here.

Freedom of Worship

Originally published February 27, 1943

Down in the valley below the hill where I spend my summers is a little white church whose steeple has been my guiding goal in many a pleasant walk.

Often, as I passed the door on weekdays when all was silent there, I wished that I might enter, sit quietly in one of the empty pews, and feel more deeply the wonder and the longing that had built such chapels — temples and mosques and great cathedrals — everywhere on the earth.

Man differs from the animal in two things: He laughs, and he prays. Perhaps the animal laughs when he plays, and prays when he begs or mourns; we shall never know any soul but our own, and never that. But the mark of man is that he beats his head against the riddle of life, knows his infinite weakness of body and mind, lifts up his heart to a hidden presence and power, and finds in his faith a beacon of heartening hope, a pillar of strength for his fragile decency.

These men of the fields, coming from afar in the uncomfortable finery of a Sabbath morn, greeting one another with bluff cordiality, entering to worship their God in their own fashion — I think, sometimes, that they know more than I shall ever find in all my books. They have no words to tell me what they know, but that is because religion, like music, lives in a world beyond words, or thoughts, or things. They have felt the mystery of consciousness within themselves, and will not say that they are machines. They have seen the growth of the soil and the child, they have stood in awe amid the swelling fields, in the humming and teeming woods, and they have sensed in every cell and atom the same creative power that wells up in their own striving and fulfillment. Their unmoved faces conceal a silent thankfulness for the rich increase of summer, the mortal loveliness of autumn and the gay resurrection of the spring. They have watched patiently the movement of the stars, and found in them a majestic order so harmoniously regular that our ears would hear its music were it not eternal. Their tired eyes have known the ineffable splendor of earth and sky, even in tempest, terror, and destruction; and they have never doubted that in this beauty some sense and meaning dwell. They have seen death, and reached beyond it with their hope.

And so they worship. The poetry of their ritual redeems the prose of their daily toil; the prayers they pray are secret summonses to their better selves; the songs they sing are shouts of joy in their refreshened strength. The commandments they receive, through which they can live with one another in order and peace, come to them as the imperatives of an inescapable deity, not as the edicts of questionable men. Through these commands they are made part of a divine drama, and their harassed lives take on a scope and dignity that cannot be canceled out by death.

This little church is the first and final symbol of America. For men came across the sea not merely to find new soil for their plows but to win freedom for their souls, to think and speak and worship as they would. This is the freedom men value most of all; for this they have borne countless persecutions and fought more bravely than for food or gold. These men coming out of their chapel — what is the finest thing about them, next to their undiscourageable life? It is that they do not demand that others should worship as they do, or even that others should worship at all. In that waving valley are some who have not come to this service. It is not held against them; mutely these worshipers understand that faith takes many forms, and that men name with diverse words the hope that in their hearts is one.

It is astonishing and inspiring that after all the bloodshed of history, this land should house in fellowship a hundred religions and a hundred doubts. This is with us an already ancient heritage; and because we knew such freedom of worship from our birth, we took it for granted and expected it of all mature men. Until yesterday, the whole civilized world seemed secure in that liberty.

But now suddenly, through some paranoiac mania of racial superiority, or some obscene sadism of political strategy, persecution is renewed, and men are commanded to render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and unto Caesar the things that are God’s. The Japanese, who once made all things beautiful, begin to exclude from their realm every faith but the childish belief in the divinity of their emperor. The Italians, who twice littered their peninsula with genius, are compelled to oppress a handful of hunted men. The French, once honored in every land for civilization and courtesy, hand over desolate refugees to the coldest murderers that history has ever known. The Germans, who once made the world their debtors in science, scholarship, philosophy, and music, are prodded into one of the bitterest persecutions in all the annals of savagery by men who seem to delight in human misery, who openly pledge themselves to destroy Christianity, who seem resolved to leave their people no religion but war, and no God but the state.

It is incredible that such reactionary madness can express the mind and heart of an adult nation. A man’s dealings with his God should be a sacred thing, inviolable by any potentate. No ruler has yet existed who was wise enough to instruct a saint; and a good man who is not great is a hundred times more precious than a great man who is not good. Therefore, when we denounce the imprisonment of the heroic Niemoller, the silencing of the brave Faulhaber, we are defending the freedom of the German people as well as of the human spirit everywhere. When we yield our sons to war, it is in the trust that their sacrifice will bring to us and our allies no inch of alien soil, no selfish monopoly of the world’s resources or trade, but only the privilege of winning for all peoples the most precious gifts in the orbit of life — freedom of body and soul, of movement and enterprise, of thought and utterance, of faith and worship, of hope and charity, of a humane fellowship with all men.

If our sons and brothers accomplish this, if by their toil and suffering they can carry to all mankind the boon and stimulus of an ordered liberty, it will be an achievement beside which all the triumphs of Alexander, Caesar, and Napoleon will be a little thing. To that purpose they are offering their youth and their blood. To that purpose and to them we others, regretting that we cannot stand beside them, dedicate the remainder of our lives.

The Best Movies to Watch This Fall

Noted film critic Bill Newcott, creator of AARP’s “Movies for Grownups,” offers his picks for the coming season.

Murder on the Orient Express (Nov. 10)

Kenneth Branagh (who also directs) stars as Hercule Poirot in the second big-screen version of Agatha Christie’s classic. When a train passenger (Johnny Depp) is killed in his compartment, Poirot gets to work probing an all-star cast of suspects, including Michelle Pfeiffer, Willem Dafoe, Penelope Cruz, and Judi Dench.

Darkest Hour (Nov. 22)

For those who complained that Christopher Nolan’s summer blockbuster Dunkirk failed to give sufficient context for Britain’s defining event at the outset of World War II, here comes Darkest Hour, the compellingly human story of how Winston Churchill summoned his country’s resolve when all seemed lost.

Gary Oldman gives the performance of the year — and perhaps of his life — as Churchill, thrust into the position of prime minster at the very moment Hitler is absorbing all of Europe under the Nazi banner. Alcoholic, physically frail, and haunted by his disastrous military experience in World War I, he’s a guy who dreamed of being prime minister his whole life … only not under such dire circumstances.

No sooner has Churchill moved into 10 Downing Street than virtually the entire British army finds itself stranded on a beach in Dunkirk, just across the English Channel but out of reach of transport ships, which are being relentlessly bombed by German planes. Besides facing external threats, Churchill is almost immediately undermined by outgoing prime minister Neville Chamberlain (Marigold Hotel co-star Ronald Pickup) and the weaselly Lord Halifax (Game of Throne’s Stephen Dillane), who has designs of his own on the prime minister’s office. These two desperately want to negotiate with Hitler and are more than willing to hand over Europe if he’ll just keep his mitts off Dear Old Blighty.

Oldman’s Churchill, battling depression and personal demons, barely has the strength to summon his own courage, much less instill it in his countrymen. But in a truly enchanting — and, I’d guess, wholly fanciful — scene, he finds himself riding a crowded London underground train where, to his utter astonishment, he finds the brave words of ordinary folks inspiring him to do the right thing.

The greatness of immortal leaders, Darkest Hour tells us, is generated not from within themselves, but from the wisdom and vision of those they lead. A powerful lesson for Winnie, and one worth remembering 77 years later.

The Current War (Nov. 24)

How’s this for a crackerjack movie idea: Thomas Edison goes to war with George Westinghouse over how best to deliver electricity to the masses: AC or DC.

What, you’re not at this moment frantically dialing Fandango to reserve your tickets? Well, it’s surprising how much mileage writer Michael Mitnick (TV’s Vinyl) and director Alfonso Gomez-Rejon (Me and Earl and the Dying Girl) get from the premise — and how compelling Benedict Cumberbatch (Edison) and Michael Shannon (Westinghouse) are in their roles.

Every schoolkid knows (or should know) the story of how Edison experimented with thousands of possible filaments for his light bulb before hitting on the one that could burn for hundreds of hours. But getting light bulbs into America’s homes was one thing; pushing the necessary electricity through wires into every U.S. neighborhood was quite another. Edison’s preferred direct current system required transformers every couple of miles, but was so safe you could press your hand to a bare wire and not get shocked; Westinghouse’s alternating current could travel hundreds of miles but, if handled without insulation, would cause instantaneous death.

And so the drama unfolds, the two men feuding from afar, sniping at each other in the press, secretly envying each other’s unique elements of genius. Cumberbatch’s Edison has the boyish charm that endeared the inventor to America, masking an all-consuming ambition. As a Westinghouse, Shannon presents a guy who is more businessman than visionary, a gentleman appalled by his rival’s dirty play (Edison convinces the State of New York to execute a prisoner via AC current and then goes about declaring that the man had been “Westinghoused”).

If you’re wondering who won the AC-DC debate, be my guest and stick a finger in the nearest wall socket. For a gentler and more appealing charge, experience the enlightening history of The Current War.

The Shape of Water (Dec. 8)

Imagine E.T., only instead of outer space, the alien is from beneath the sea, and instead of a little boy named Elliot, the hero is a mute middle-age cleaning woman named Elisa, and instead of hiding in a closet, the alien stays in Elisa’s full bathtub.

As in E.T., the alien is the subject of a U.S. government search that is likely to end in his death and dissection. Unlike E.T., there’s quite a bit of nudity and just a smidge of alien-human sex.

Those are the ingredients of Guillermo del Toro’s The Shape of Water, at once a nearly beat-for-beat remake of Steven Spielberg’s 1982 classic and also a uniquely grown-up fable of forbidden love, high adventure, and magical images. From the opening shot — Elisa’s dream of living underwater, her apartment furniture bobbing about as if the place were a submerged Titanic stateroom — del Toro immerses us in his unique brand of Fantasyland… forbidding and irresistible, dangerous and delightful.

Sally Hawkins (Maudie), ratcheting up her Adorable Quotient to DEFCON 1, stars as Elisa, a meek and mute laborer who operates a bucket and mop at a top-secret government research laboratory along with her adoring partner Zelda (Octavia Spencer). Behind one heavily fortified sliding door, they encounter a most unusual research subject: a Creature from the Black Lagoon-type character with whom Elisa strikes up a tentative after-hours friendship.

It’s not much of a relationship at first, just some informal sharing of hard-boiled eggs. But soon they’re conversing in sign language and listening to Benny Goodman records together, and when Elisa learns that a cruel-hearted military scientist (Michael Shannon) is planning to cut the critter open to see what makes him tick, she engineers a brave and daring escape plan.

Once Beauty and the Beast are alone in that apartment, well, that’s when the similarities to E.T. take a momentary leave of absence.

Shannon, whose performances here and in The Current War embody his startling versatility, plays the heavy with Big Bad Wolf ferocity, his performance tempered by some revealing glimpses of his unhappy home life. Richard Jenkins, always a welcome sight, turns up as Elisa’s artist neighbor, a struggling illustrator whose own tentative search for affection inevitably ends in cold rejection. The two men’s hollow lives add to the poignancy of the film, infusing it with a sense of yearning, a melancholy Elisa just might be able to break through with her most unusual love.

Visionary as always, del Toro (Pan’s Labyrinth, Hellboy) brings his uniquely Mexican celebration of the fantastic and grotesque to bear in The Shape of Water. Next up: His take on that darkest of fairy tales, Pinocchio. I can’t wait.

Star Wars: The Last Jedi (Dec. 15)

When we glimpsed Luke Skywalker at the end of 2015’s The Force Awakens — 32 years after his previous appearance in Return of the Jedi — he was just sort of standing around atop a cliff. We’re guessing Luke (Mark Hamill) will have a lot more to do in this follow-up, including, we hope, a reunion with his sister, Princess Leia (played by the late Carrie Fisher in her final role).

This article is featured in the November/December 2017 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Follow Bill Newcott at saturdayeveningpost.com/movies or at his website, moviesfortherestofus.com.

Cartoons: Heaven Help Us!

September 1, 2002

July 1, 2004

March 1, 2009

March 1, 2009

November 1, 1995

March 1, 1995

But I don’t feel right without underwear.”

March 1, 1995

News of the Week: Two Spaces vs. One, Boomers vs. Millennials, and House Hunters vs. Vintage Homes

A Typing Controversy

Like a lot of people of a certain age, I took a typing class in high school. I hated it and didn’t do well, which always makes me chuckle because now I actually type for a living, every single day. I think what I disliked at the time was having to sit a certain way, holding my hands in a certain position, endlessly recording the events of all good men who come to their country’s aid. Like a kid who just wants to play the guitar instead of learning chords or how to read music, I just wanted to type. Also, my teacher looked a lot like Larry Fine of the Three Stooges, and that distracted me.

One thing I remember from typing is you needed to put two spaces after a period. But that’s not really true online, and that has a lot of people who still like to put in two spaces a little, well, irritated. In this piece at Mel, amusingly titled “For the Love of God, Stop Putting Two Spaces after a Period,” John McDermott explains in detail why you should now only put one space after a period. In this follow-up piece, McDermott explains how a lot of people didn’t like to be told to put only one space after a period and let him know it in often colorful, vulgar terms (and often using only one space after a period).

I’ve never really thought about how many spaces come after periods in print books and magazines and newspapers. It does really stick out when I get an e-mail where someone uses two spaces. Now I’m going to really notice it, and it’s probably going to drive me batty.

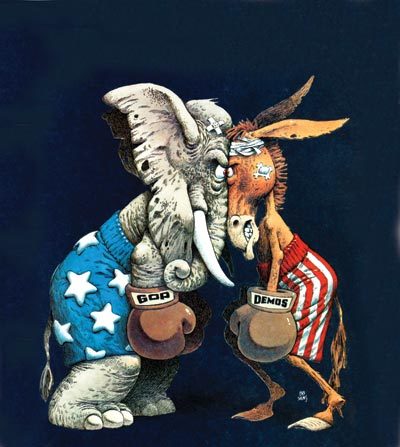

Boomers vs. GenXers vs. Millennials

Every generation complains about the generation that preceded them. Millennials blame Generation X for everything, Generation X blames Boomers for everything, and Boomers blame The Silent Generation, who then blame The Greatest Generation. At least I think that’s how it goes. It’s hard to keep track of who is named what when and why.

I have a slightly different take. I’m a GenXer, and I’ve never blamed Boomers for anything. It never occurred to me to blame Boomers. Instead, like any normal GenXer or Boomer, I complain about Millennials.

BuzzFeed has the results of a poll conducted by the Ipsos firm that found out what older people and younger people think they should do to be considered an adult. The topics range from living at home and doing your own laundry to paying your own bills and having an annual medical checkup.

Shouldn’t all of these numbers be near or at 100 percent? Not every category for every age group, of course, but some of these numbers seem low to me. Only 39 percent of people aged 35–54 consider cooking for themselves more than twice a week to be a sign you’re an adult? Only 43 percent of those aged 18–34 think getting no financial support from their parents is a sign you’re an adult? Only 16 percent of everyone polled gets a flu shot? I’d love to see a similar poll taken in 1980 or 1960.

Some of the results shock me, but not as much as finding out that the word adult is now used as a verb.

And the Tony Nominees Are …

I could go into detail about this year’s Tony nominations. About how this person or this show got a lot of nominations or how this person was snubbed or what the nominations mean. But I haven’t seen any of the shows, don’t really know much about the shows, and I’ve never been to a Broadway show. But here’s the list of this year’s nominees. You probably know more than I do.

The awards show will air June 17 on CBS.

Strike Averted!

Three weeks ago, I told you about a possible writers strike that was about to hit Hollywood. But now we don’t have to worry about it because the two sides came to an agreement at the last minute on Tuesday. It’s a three-year deal that gives writers more money (including increases in residuals), expanded contract protection, and changes to healthcare.

Now, if you were actually hoping for a Hollywood strike, you might be in luck: An actors strike could be next.

Frozen in Time

Whenever I watch House Hunters I get a little irritated, for two reasons. One, I don’t really believe that the show is completely honest. The setups seem staged, and everything is a little too scripted (and a 2012 investigation seems to back up that theory). Second, I hate when the couples are shown an older home, maybe a midcentury home with its original rooms and design and appliances, and the first thing that comes out of their mouths is “we have to tear this out!” I hate that. Those homes should be owned by people who want to keep most of the original features intact.

Like the people shown in this Wall Street Journal piece titled “Life Inside a Time Capsule.” It’s about people who buy older homes and decide to keep them the way they’ve always been, almost like living their lives the way the previous owners lived theirs decades ago. The slideshow is terrific, even if some of the designs of the ’70s homes may disorient you for a moment.

RIP Florence Finch, Norman T. Hatch, Colonel Bruce Hampton, Lorna Gray, Trustin Howard, Leo Thorsness, and Bruce Hall

Florence Fitch was a World War II hero whose bravery wasn’t even known to the public until decades later. She actually died on December 8 at the age of 101, but her family didn’t make the announcement until this week.

Norman T. Hatch had a connection to World War II as well. He was a Marine cinematographer whose shocking footage of a battle in the Pacific won him an Academy Award in 1946. He died April 22 at the age of 96.

Colonel Bruce Hampton was considered the “Godfather of the Jamband Scene” and played with such people as Frank Zappa, Blues Traveler, Spin Doctors, and Widespread Panic, as well as many of his own bands. He collapsed on stage on Monday during a birthday celebration. He was 70.

Lorna Gray was an actress who appeared in several shorts of the aforementioned Three Stooges and in movies with people like John Wayne and Buster Keaton, as well as many other films during the ’30s, ’40s, and ’50s. She passed away Sunday at the age of 99.

Trustin Howard was the head writer of The Joey Bishop Show and often acted in movies under the name Slick Slavin. He died in April at the age of 93.

Leo Thorsness was an airman held captive along with John McCain in the prison known as “The Hanoi Hilton” during the Vietnam War. He died Tuesday at the age of 85.

Bruce Hall was a CBS newsman for 20 years and an NBC newsman for 17 years. He covered space for both networks, as well as thousands of other stories. He died Tuesday at the age of 76.

This Week in History

Citizen Kane Premieres (May 1, 1941)

The classic Orson Welles film had its world premiere at the RKO Palace Theatre in New York City. The movie is usually on “best movies of all time” lists, including this critics poll in The Saturday Evening Post in 1978.

Hindenburg Explodes (May 6, 1937)

Here’s how reporter Herbert Morrison described the event on the ground. By the way, this is how Morrison actually sounded. The video we usually see has an audio recording that was running too fast, and Morrison’s voice has always sounded higher than it was.

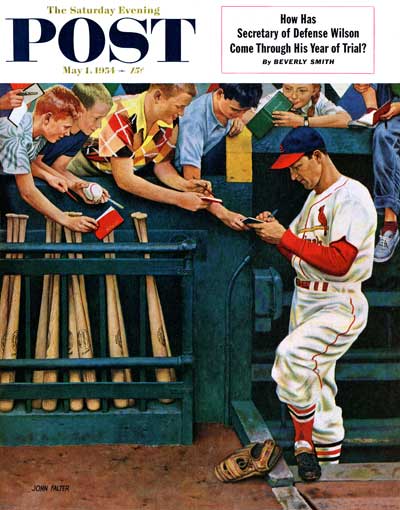

This Week in Saturday Evening Post History: Stan the Man Cover (May 1, 1954)

John Falter

May 1, 1954

The man called Stan was Stan Musial, outfielder and first baseman for the St. Louis Cardinals, and in this cover from John Falter, he’s shown signing autographs for fans. Here’s the profile from that issue of the Post, titled “The Mystery of Stan Musial.”

May Is National Hamburger Month

Who invented the hamburger? It’s an odd thing to think about since it seems to have been with us forever. Taking a look at the Wikipedia page for hamburgers (yes, there’s a Wikipedia page for hamburgers), a version of its origin story goes all the way back to 1758, but it’s not really the modern one we enjoy. Some people say the first hamburger was served at Louis’ Lunch in New Haven, Connecticut, in 1900. Others say it was Charlie Nagreen in 1885 (a meatball sandwich), while White Castle says it was the invention of Otto Kuase in 1881. And that’s only three of the many possible inventors. There’s a dispute because it all comes down to not only when it was invented but also what the exact definition of hamburger is.

Someone should make a movie about it.

Here are three burgers to make this month: a Spiced Buffalo Burger from Emeril Lagasse, a Turkey-Meatloaf Burger from Martha Stewart, and a Cheese-Stuffed Burger from country star Trisha Yearwood.

By the way, if you do get a hamburger this month and have to borrow the money to do so, make sure you pay it back by Tuesday. Like Wimpy.

Next Week’s Holidays and Events

V-E Day (May 8)

Also known as “Victory in Europe” Day, it’s the day in 1942 when we celebrated the formal surrender of Germany, which ended World War II in Europe.

National Teachers Day (May 9)

In April, the 2017 Teacher of the Year was honored at the White House. Her name is Sydney Chaffee, and she teaches at the Codman Academy in Boston.

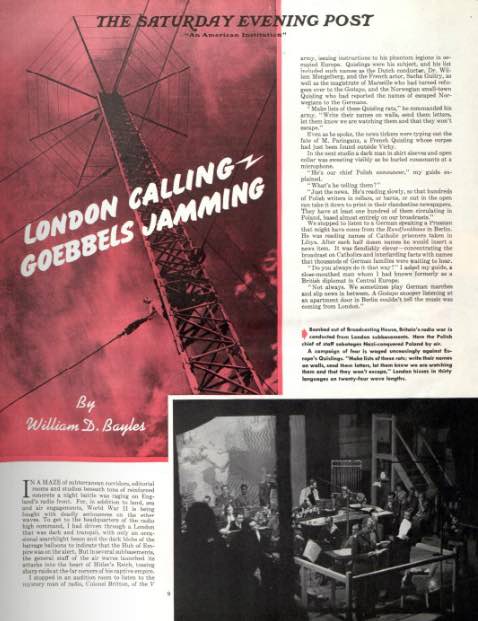

How the British Beat the Germans at Their Own Propaganda Game: 75 Years Ago

Large-scale public propaganda campaigns were introduced in World War I, but they became more far more elaborate, and effective, in World War II.

Large-scale public propaganda campaigns were introduced in World War I, but they became more far more elaborate, and effective, in World War II.

In 1914, Allied propaganda consisted of simply spreading stories of German soldiers committing atrocities. Newspaper readers in both Allied and neutral nations were told that innocent men, women, and children were being maimed and killed in Belgium and France by German troops. Though never substantiated, the stories helped swing public opinion firmly against the Germans.

By World War II, Germany had become master of the art of propaganda, building one of the most sophisticated mis- and dis-information machines in the world. The Minister for Enlightenment and Propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, knew the importance of radio in spreading the Nazi message. He authorized the manufacture of inexpensive radios that would be affordable to more people. He even gave away free radios on his birthday.

Radio broadcasts played on the familiar themes of German National Socialism. Wrapped around music programming, Goebbels would include short pieces that appealed to Germans’ resentment at the outcome of the last war and their depressed standard of living, which he skillfully blamed on Jews, communists, and unpatriotic Germans. Through his efforts, the Nazi government gained the loyalty of otherwise sensible Germans and convinced them to sacrifice their efforts, fortunes, and lives for Hitler.

But England soon proved as adept at the game as Germany. In “London Calling — Goebbels Jamming,” William Bayles describes the impressive operations at the British Broadcasting Corporation, which provided news and persuasion throughout Europe and the Middle East.

The BBC enlisted the help of national resistance heroes like Queen Wilhelmina of Holland and Charles De Gaulle of France to speak to their conquered people over the airwaves. It also drew on a vast pool of refugees who’d sought asylum in England and who could write and speak languages of all the major nationalities in the war zones: 24 nationalities in all — from Albanians to Turks – prepared “ammunition for the radio offensive against Hitler.”

And while the Germans distorted the facts in their news, the British made a point of being honest in their reporting. They believed the blitz-propaganda machine, which repeated lies until they were believed, would someday fail. When Hitler eventually exhausted the trust of the German people, they would know where to find a more reliable source.

The British were also particularly good at using an enemy’s words against them. The BBC would edit clips from Hitler’s different radio speeches to show him repeatedly contradicting himself.

Perhaps nothing was more effective than the way the BBC ended its German broadcasts every day. Listeners heard “a clock ticking hollowly and a ghostly voice intoning: ‘Every seventh second, a German soldier dies in Russia. Every seventh second … hour after hour … day after day … Is it your husband … your son … your brother? Shot … drowned … frozen … every seventh second … seven … seven.’”

The Average American Today and on the Eve of World War I

The First World War, which the U.S. entered 100 years ago today, is so far in our past that it can feel like ancient history. How can we understand the U.S. of 1917 when so much has changed since then?

One way is to compare what it means to be an “average American” then and now, though we’re fairly certain that Saturday Evening Post readers are, on the whole, above average.

If you were an average American on this day in 1917, you were one of 103 million citizens. (Today’s population is over 320 million.) Being a typical 1917 American, you would be among the 86 percent of the population that was Caucasian, and you would live on a farm or in a town with a population of 2,500 or less. Because of your rural locale, you wouldn’t have heard about that new American music called “jazz” that was brewing in the big cities; it had only been recorded for the first time in March.

Suppose you were the typical woman of 1917. You’d be between the ages of 15 and 19, but you wouldn’t get married until you were 21. You had a life expectancy of 49 years (today it’s 78.8 years). You couldn’t vote, you couldn’t obtain birth control, and you had no education beyond the eighth grade. You were living in your parents’ house. You washed your hair just once a month, and you would probably deliver all three of your babies at home.

But the typical American in 1917 was a man; the majority of Americans were male until the 1950s. As an average American, adult male, you were between 20 and 24 years old with a life expectancy of 47 years.

You worked 55 hours a week for 22 cents an hour, but your income wouldn’t go as far in 1917 as it does today. For example, you would spend 33 percent of your earnings on food (compared to 16 percent today). Every year, you would consume 11.5 pounds of lard, 14 pounds of chicken (it’s over 90 pounds today), and 88 pounds of sugar (at 4 cents a pound). Also, your clothing expenses took up 13 percent of your annual income, compared to just 3 percent today. You’d need to save up almost an entire year’s income to buy the average new car, which cost around $450 (today it’s around $34,000).

However, if you were in the fortunate minority that owned one of the 4.7 million cars on America’s roads in 1917, you would pay as much as 20 cents for a gallon of gas (the equivalent of $3.81 per gallon today). And if you lived in any city, the law would prevent you from traveling faster than 10 miles per hour.

The average new home today costs $390,000. If you had bought an average new home in 1917, it would cost $5,000 (the equivalent of $95,000 in today’s dollars), and you’d share it with four other people instead of the 2.3 others you’d share it with today.

As an average American, you wouldn’t be among the fortunate 14 percent of the population whose homes had bathtubs with running water, or the 18 percent of households with at least one live-in servant. Also, you’d have no phone in your home; that was a privilege enjoyed by only 8 percent of Americans. Instead, your long-distance communication would be done by mail, though Americans sent six times more telegrams than letters.

As a typical male in 1917, you wouldn’t have graduated from high school — only 10 percent did so — but at least you could read and write (25 percent of Americans couldn’t). You would be considered ready for military service. Before the war was over, if you were between 18 and 31, you had a 25 percent chance of serving in uniform, as either a draftee or a volunteer.

If you did end up as an average soldier in the armed forces, you would be 25 years old, 5 feet, 7½ inches tall, and a compact 144 pounds, with a 31-inch waist and 14-inch neck. Most likely, you would be among the 4 million American men who served in the American Expeditionary Forces. If so, you had a 50/50 chance of serving overseas, a 5 percent chance of being wounded in battle, and a 1.3 percent chance of being killed in the fighting. But, as a typical G.I. (a term that wouldn’t be in use until the next world war), you would not be among the 43,000 servicemen who died of influenza during and after the war.

However, when you got home in 1918 after surviving the flu epidemic and the war, you would no longer be the typical American you’d been in 1917.

Alien Enemies: America’s Persecution of German Citizens During World War I

The news in early March of 1917 wasn’t good. Americans learned that German submarines were going to resume their attacks on all ships heading to England. Just days later, the U.S. government released the text of the Zimmerman Telegram, an intercepted message from Germany to Mexico. If the U.S. entered the war, it read, and Mexico declared war on the U.S., a victorious Germany would force America to return the territories of Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona to Mexico.

Even before these news items, American opinion had generally turned against the German cause. It had been Germany, after all, who sank the Lusitania. And it was probably Germany who blew up an island in New York Harbor where the U.S. had been storing ammunition.

Now, as war drew closer, the country was growing more apprehensive about spies and saboteurs working for Imperial Germany. Many Americans suspected their German neighbors of being foreign agents. Pro-war propaganda in the newspapers helped to further demonize all Germans in Americans’ eyes. The public’s fears were shared by the federal government, which pondered how it would handle aliens from an enemy nation.

It was a problem that the U.S. would struggle with in subsequent conflicts.

In “Alien Enemies,” an article from the March 17, 1917, issue of the Post, author Melville Davisson Post describes how Great Britain developed its approach to handling German aliens. Based on Britain’s experiences, he recommends the U.S. take aggressive measures against anyone of German ancestry in America, including stripping naturalized German Americans of their citizenship and subjecting them to military justice. He also urges the forcible relocation of all resident aliens away from areas of military significance.

When war did come, President Wilson signed orders that labeled all Germans in America “enemy aliens.” He barred them from working in or near military facilities or Washington, D.C. This caused so many Germans to lose their jobs that the Labor Department feared a serious shortage of manpower.

All Germans had to register with the Post Office and carry identification papers at all times. German business owners had to open their account books to authorities. In several states, the attorney general ordered that Germans’ bank accounts be made public.

Several orders appear to have been motivated more by profit than national security. Late in the war, Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer seized the assets of German companies in the U.S., which were then sold to Americans. And just days before the war ended, the U.S. confiscated the patent rights of Germans, which included the patents to valuable industrial chemicals and medicines.

The enemy alien laws affected 250,000 German men and 6,300 German women. Out of this number, the Justice Department’s Enemy Alien Registration Section incarcerated 2,048 Germans. Some, like Karl Muck, the conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, left America when released from camp and refused to ever return.

Those Germans who avoided detention endured harassment and vandalism from Americans throughout the war.

In later years, it became clear that the government’s actions against Germans had been excessive and did little to protect the country from enemy sabotage or subversion. Yet America was destined to repeat the mistake 25 years later with its Japanese citizens during World War II.

The author discusses Great Britain’s solution to the problem with German citizens living in England while it was fighting Germany. Though the U.S. wasn’t yet in the war, he believed German agents were already in America and recommended rigorous methods for isolating both Germans citizens and naturalized citizens from Germany.

Featured image: Photo from Brown Brothers, New York City, from “Alien Enemies” in the March 17, 1917, issue of the Post.

Cover Gallery: Take Flight

America has always been in love with the concept of flight. From the first bi-planes to futuristic bombers, these Post covers fly you through a short history of aviation.

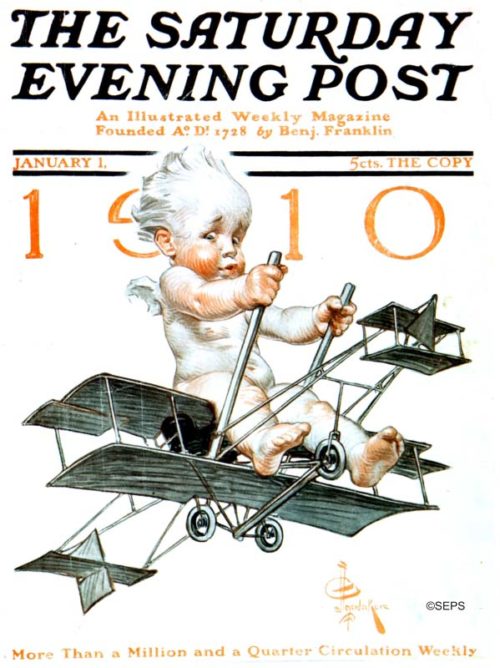

By J.C. Leyendecker

January 1, 1910

J. C. Leyendecker painted numerous “Baby New Year” covers, which often narrated the issue of the day: The 1910 baby flew a new-fangled bi-plane. The 1912 baby carried a “Votes for Women” sign. And 1914’s tot cruised the soon-to-be-opened Panama Canal. The worried face of our bi-plane baby reflects the trepidation many had about this brand-new mode of travel.

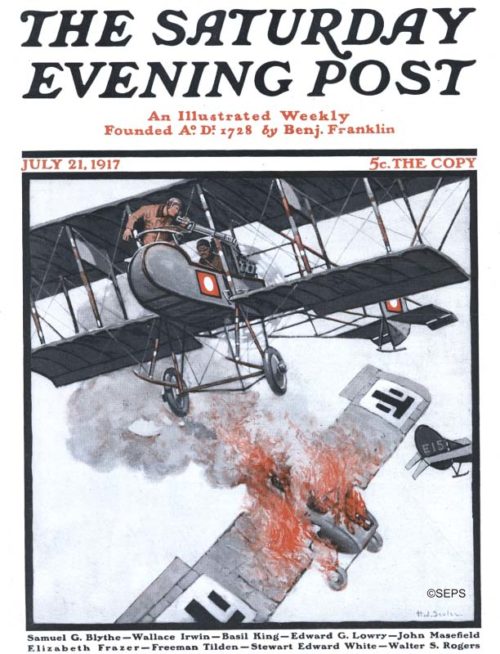

Henry J. Soulen

July 21, 1917

This dramatic aerial scene from a World War I dogfight depicts the moment of victory. Air combat was extremely rare at the beginning of the first world war. Although there was some tactical use of planes during the war, they were mostly used for reconnaissance. Over the course of the war, air battles evolved from grenades to handheld firearms, and eventually machine guns. The victorious plane has a pusher configuration, where the propeller is located behind the pilots. This solved the problem of the propeller interfering with the gunner’s line of sight.

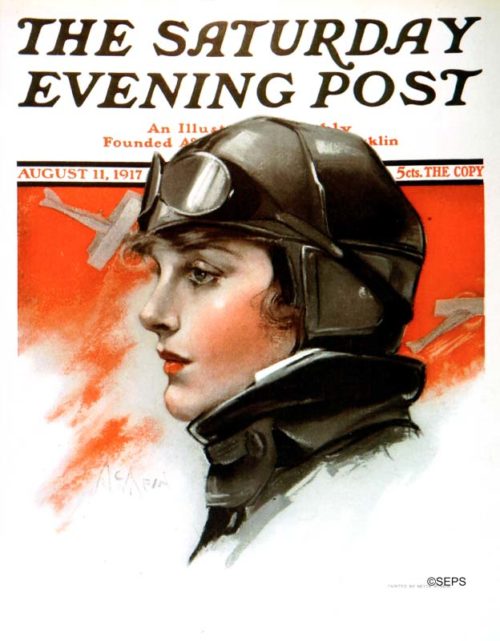

Neysa McMein

August 11, 1917

Neysa McMein got her start as an illustrator during World War I, travelling across France with Dorothy Parker to entertain the troops. She is known for creating the “Betty Crocker” image for General Mills, but this cover, as well as her inclusion in the Algonquin Roundtable, suggests a life that was perhaps more progressive than the fictional Mrs. Crocker’s.

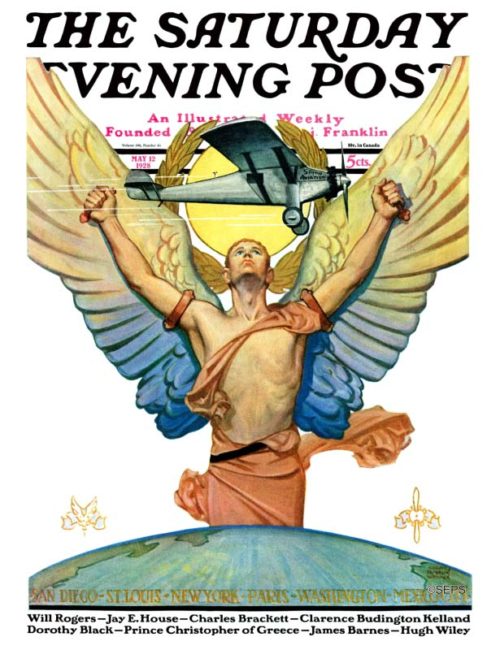

Edgar Franklin Wittmack

May 12, 1928

Edgar Franklin Wittmack was one of the top magazine cover illustrators from the 1920s to the 1940s, whose resume would include 22 Post covers. Wittmack’s covers often featured manly men — cowboys, mariners, Mounties, and movie stars —striking a jaunty pose for the portraitist. This ethereal, deco-style illustration was somewhat of a departure from his other Post covers.

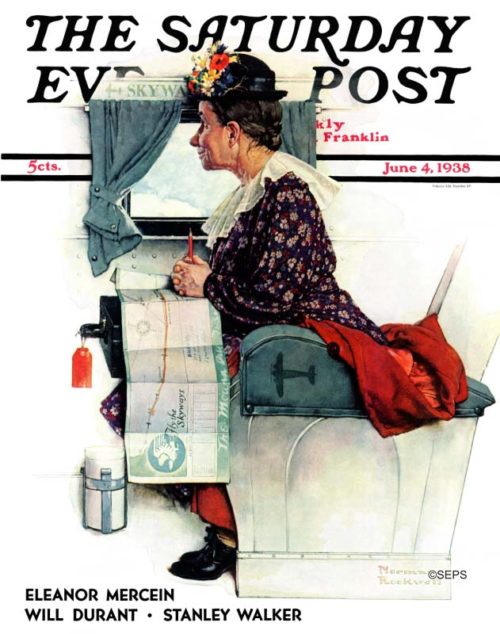

Norman Rockwell

June 4, 1938

Although this Rockwell illustration doesn’t feature a plane’s exterior, we couldn’t help but include this charmer. This eager first-time traveler gazes out the window, the route painstakingly traced out on her “Fly the Skyways” map. The rich narrative quality of the scene is the hallmark of Rockwell’s most compelling images.

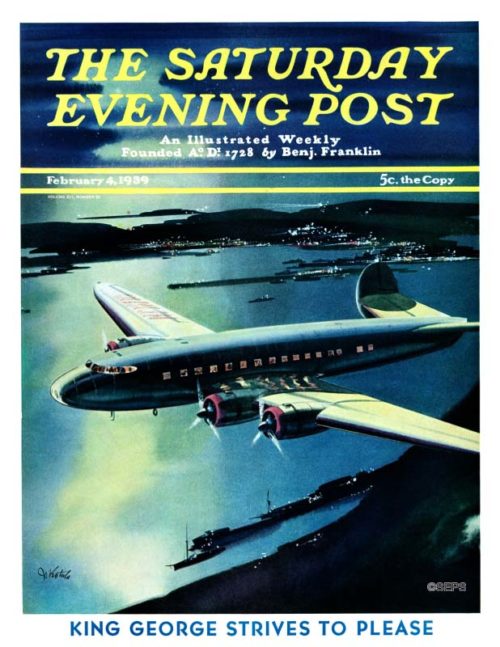

By Josef Kotula

February 4, 1939

This dramatic night scene is the only cover Josef Kotula painted for the Post. Kotula was known for his futuristic aviation and spaceship illustrations.

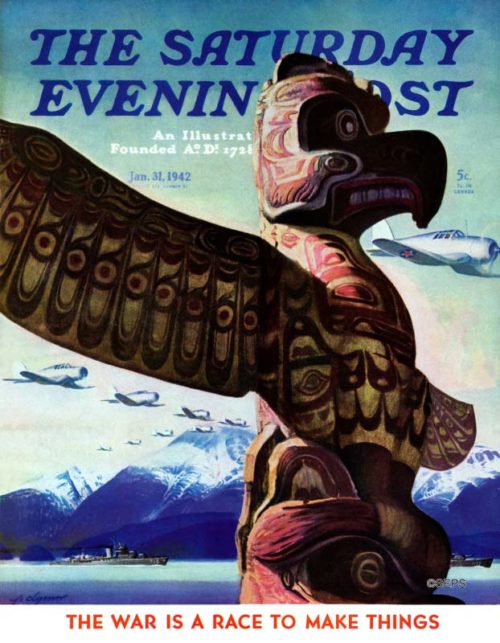

John Clymer

January 31, 1942

The U.S. had just entered World War II, and Clymer dramatically illustrated America’s commitment to protecting its Pacific shores. Both warships and planes glide across the dramatic backdrop of the Alaskan frontier, as the totem pole stands guard in the foreground, ever vigilant for invaders.

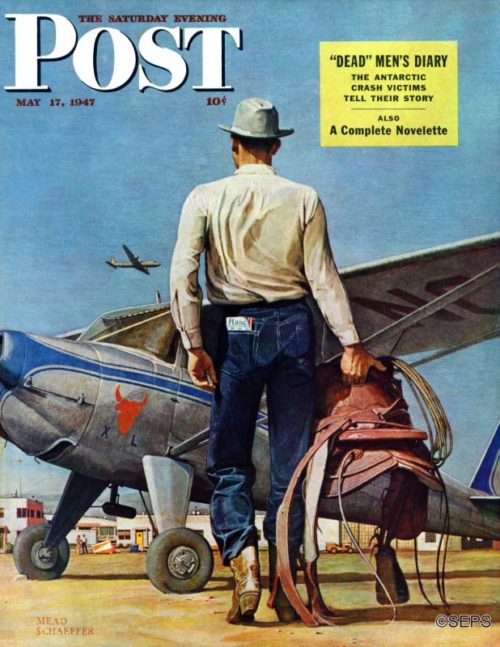

Mead Shaeffer

May 17, 1947

“The cowboy carrying his pet saddle to his plane is an everyday sight in the West,” artist Mead Schaeffer wrote when he delivered this painting. “Many a rancher lives in town and commutes to his ranch or ranches by air. The tableland makes landing fields all through the West, and because of the long distances involved, the West takes to planes the way the East take to cars. Many a business engagement, even luncheon engagements, are kept this way.” One of the flying ranchers, Lee Bivins, was Schaeffer’s model. The background is the airport at Amarillo, Texas.

Robert McCall

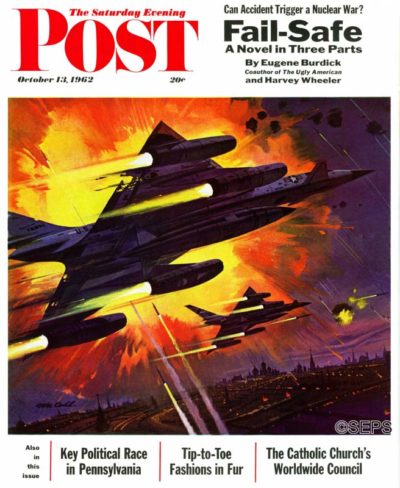

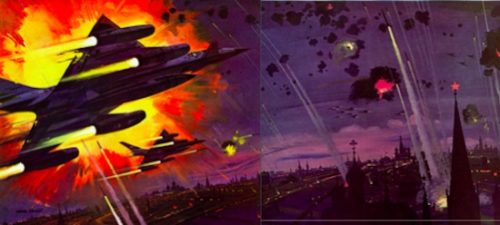

October 13, 1962

This cover by Robert McCall accompanied a serialization of the book Fail-Safe, which described what might happen if a communications breakdown should cause nuclear-armed bombers to fly past their point of recall. The illustration depicts American bombers approaching Moscow, which is more obvious when one sees the two-page fold-out cover in its entirety. The Post editors wrote, “Accidental warfare is a valid subject for consideration in these cold-war days, and we would do well to keep in mind the grave problems facing the President—and all of us—in keeping the peace.”

Call of Beauty: Rationed Fashion on the Home Front

By the time Americans entered World War II after the attack on Pearl Harbor, they had already been feeling the effects of shortages.

Gas was still available in the fall of 1941, but gas stations were reducing their hours of operation to help conserve energy.

New cars weren’t in short supply yet, but automakers were reducing their production of passenger cars to build more airplanes and tanks. Businesses were warning Americans to take better care of their cars because it might be a long time before they could be replaced.

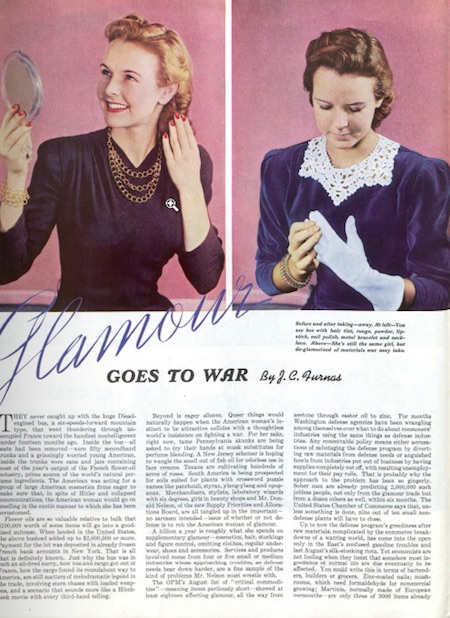

Of all the industries affected by the war, though, none brought the effect of war closer to Americans than the glamour business.

As J. C. Furnas points out in his November 29, 1941, article, “Glamour Goes to War,” American women were coping with shortages of cosmetics and stockings well before 1941. Embargoes and blockades halted the export of essential perfume oils from France, Bulgaria, Tibet, and Zanzibar. Necessary ingredients for lipstick and hair dye were no longer available from warring nations. Chemical solvents in nail polish were being requisitioned for military purposes. Even the brass used for lipstick containers was in short supply.

Almost all available silk had been purchased by the Defense Department to make parachutes and tents. Nylon stockings should have been the economical alternative. They had been introduced in May 1940, and 64 million pairs had been sold within the first year. But the raw materials of nylon were being used in the war effort, and women who wanted to avoid a bare-legged look were painting seams up their calves.

When the military began buying up the market supply of textiles, the fashion industry responded to the shortages by using less fabric in dresses. Hemlines went up and unnecessary detailing was dropped.

When cosmetics began to disappear, there was no matching movement to cut back on lipstick and powder. European perfume ingredients were replaced with synthetics, and whale spermaceti used in lipstick was swapped for more domestic lubricants.

Women continued to pursue the conventionally feminine image, even when operating heavy machinery in a B-17 plant. Advertisers encouraged this attitude, telling women it was their patriotic duty to maintain their looks for their men in uniform. The author himself warns that “many women, deprived of the usual makings of charm, would lose the personal self-confidence that helps bolster them through the ills of life.” The thought of 40 million women “reverting to Nature” made everyone jittery.

Much of the article is addressed to the “man of the house,” suggesting that his wife shouldn’t panic over the shortage. She may not have heard his reassurances, having already left for work at the munitions plant.

Featured image: Photos by Constance Bannister for “Glamour Goes to War,” from the November 29, 1941, issue of the Post.

The B-17 Flying Fortress Changes the Learning Curve of World War II

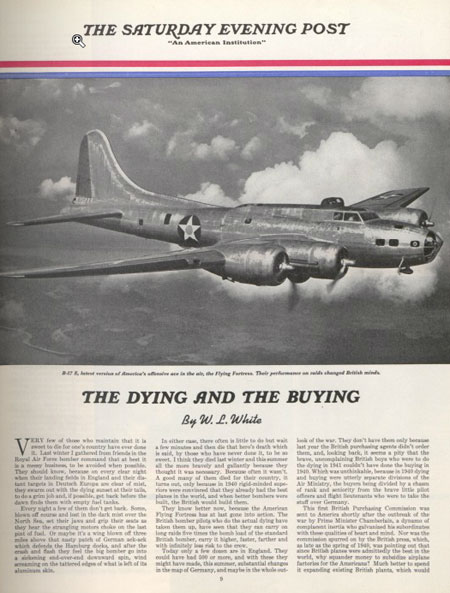

America debuted the Boeing B-17, its latest development in military bombers, in 1940. The B-17 included a feature so advanced — the turbo-supercharger — that the Army had originally prohibited its sale to any foreign power. But that prohibition had been eased for the British now that they were fighting for their survival.

The British weren’t impressed.

They dismissed Boeing’s Flying Fortress as too new and too complicated. Also, it wasn’t British. So the Royal Air Force launched its air offensive against Germany with the older British bombers. In the following months, the RAF suffered losses so heavy, they reconsidered the American bomber.

By 1941, the British were flying B-17s and, according to author W. L. White, they were hitting the enemy harder, more frequently, and with less risk to the crew. This prompted White to reflect on the lives of airmen lost to the stubborn thinking of British military planners.

For the first few years of the war, the Allies — both British and American — struggled to get ahead of the Germans on the technology curve. The Nazis had been planning their conquest for years. Their opponents had looked away from the growing crisis, not wanting to think about another war so soon after the last one.

When war began, the Allied nations assumed it would be fought much like the First World War: a long stalemate with trench-bound troops and occasional bombings. That notion was shattered in June of 1940, when the Germans swept across Europe to conquer France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands. The world was stunned.

Here in America, many who had considered the new war as a pointless repeat of World War I now began to urge the U.S. to rebuild and modernize its military.

But re-arming the nation would be expensive and time-consuming. On December 7, two months after “The Dying and the Buying” appeared in the Post, the Japanese sped up the modernization of the U.S. Pacific fleet by destroying much of its power at Pearl Harbor.

As you read this article, keep in mind that Flying Fortresses were taking people farther from earth than ever before: the turbo-supercharger enabled the B-17 to operate at 30,000 feet. White explains how designers overcame the challenges to aviators operating at such high altitudes.

The Politics of Rage

America has witnessed heated presidential campaigns before, but seldom with the level of vociferous anger being expressed this year. While much of the rage seems to be directed at “others” — Mexicans, Muslims, and immigrants from all over — many have pointed out that its true source is the enormous social and economic shift brought about by technology. As author Michael Kimmel argues in his book Angry White Men, many voters feel “betrayed by the country they love, discarded like trash on the side of the information superhighway.”

Where does reasonable anger at bad luck or circumstance end and irrational hatred begin? For historical perspective, a lesson can be drawn from World War II, when rage against the Japanese bubbled over following the attack on Pearl Harbor. At the time, motion pictures, cartoons, and propaganda depicted the Japanese as buck-toothed, semi-human caricatures. No less a figure than General John L. DeWitt, head of the Western Defense Command, told Congress at the time, “The Japanese are an enemy race. We must worry about the Japanese all the time until [they are] wiped off the face of the map.”

Even at the height of World War II, most Americans were outraged by such rhetoric. In a 1943 editorial, the Post lauded “the wave of indifference which greeted the recent effort of a small group of super-duper patriots to make the rest of us feel guilty for not hating the enemy enough.”

More hate, the editors pointed out, was not an answer to the world’s problems, nor would it lead the Allies to victory:

“Undoubtedly, there are plenty of reasons to hate our enemies. Those who know what the Japanese have done to captured soldiers and civilians could not exclude hate from their hearts if they wanted to. But this has not much to do with winning the war, and certainly nothing at all to do with making the peace.”

“We wonder why people deplore our lack of interest in hatred,” added Pacific-based Staff Sergeant Hobert Skidmore in an article published a few months later. Speaking for his fellow soldiers, he continued, “We know the quality of hatred. But charity is greater in us than hatred. [Anger] is not an abiding and continued feeling. It is the thing that makes a soldier in combat achieve the nearly impossible. But it must be controlled. An angry man has his guard down. He endangers himself and the other members of his ship, or plane, or gun crew, or foxhole. There is a word we have in the Army for a guy who is always filled with anger and hatred. It isn’t a pretty word.

“At the right time and for the right thing, anger is valuable. A continuing hatred isn’t worth a damn. Do our civilian law officers hate criminals and lawbreakers? No, they have contempt for them and arrest them and punish them. It is a very satisfactory and democratic solution.

“Hatred we know. We are fighting an enemy capable of hatred. They really loathe us and no fooling about that. They hate us with a blind fury: You probably have noticed that they are losing the war, will lose the peace, will lose something the people of a nation should never lose.”

Today, as campaign rhetoric becomes increasingly inflamed, these reasonable words bear repeating.

Research by Saturday Evening Post archivist Jeff Nilsson.