On March 8, 1965 (50 years ago this Sunday), the first U.S. combat troops came ashore near Da Nang, South Vietnam. No one could have foreseen that the 3,500 marines who landed that day would eventually be followed by over 2.5 million American soldiers.

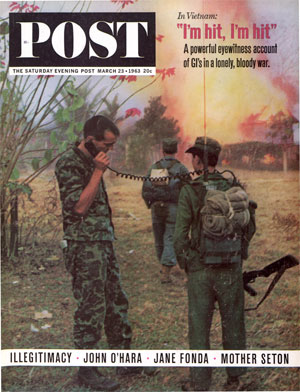

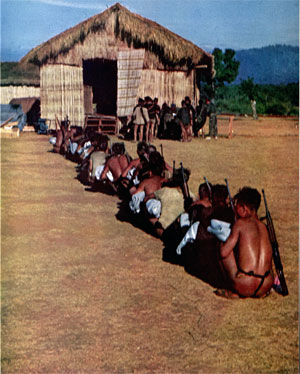

Prior to 1965, America had limited its involvement to providing South Vietnam with military supplies and advisors. On the day the marines landed, 23,000 of these advisors were already in the country. They were men like the ones journalist Jerry Rose met and later described in his 1963 Post article “I’m Hit! I’m Hit! I’m Hit!”. These members of a Special Forces “A” team were helping South Vietnamese peasants defend their villages against communist guerillas who called themselves the Viet Cong (VC).

Ten years and 58,000 American deaths later, the last GI left Vietnam under the terms of a peace accord between the U.S. and North Vietnam. Two years later, in 1975, the South Vietnam defenses crumbled. North Vietnamese tanks rolled into the South Vietnamese capital, just hours after the last Americans were evacuated from the U.S. embassy in Saigon.

Many Americans couldn’t shake the feeling that their country had been defeated and that the conflict hadn’t been worth the costs, particularly in human life. Many felt bitter toward the leaders who had drawn America into Vietnam. The war created a deep political divide in the country. For some Americans, it inspired an abiding distrust of government officials, politicians, and the military.

Given the bitterness and regret through which some view the Vietnam War, it’s interesting to read what was being said about America’s involvement in Vietnam before disenchantment and defeatism set in. In the 1963 Post article, Jerry Rose described the courage and determination of those early American advisors and the commitment of South Vietnamese villagers to take up the fight. Rose accompanied them on patrol, observed them under attack, and saw how they responded to a VC attack inside the camp in the middle of the night.

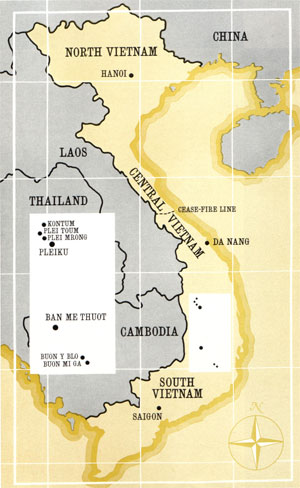

He had faith in the Special Forces officers, but he recognized they were facing hard challenges. One of the biggest was the lack of cooperation from the South Vietnamese forces. When the VC overran their base at Plei Mrong, the advisors sent a Morse code request for reinforcements. But the request was denied. “The Vietnamese Ranger company was needed for the security of Pleiku — a divisional headquarters where thousands of troops were stationed,” Rose wrote. “Similarly, the T-28 [air] squadron at Pleiku could not strike at Plei Mrong because, said the Vietnamese commander, the airstrip at Plei Mrong had no lights. One American pilot said that he’d fly the mission, strip lights or not. No, came the reply, the T-28s were now Vietnamese planes, and the Vietnamese didn’t want any of them lost.”

Another challenge was telling friend from foe in this civil war. The morning after the Plei Mrong raid, Rose wrote, an American named Billie Fell was tending to the wounded. Fell recognized one of the men, shot four times through the body, as one of the village defenders. “Having bandaged his wounds, Fell stood up and was about to move on when the man suddenly opened one eye. The eye glinted in the flare light as the wounded man stated proudly in English: ‘Me Number One VC.’”

Despite the challenges, Rose had faith in the advisors. Courageous and professional, they shrugged off any suggestion that they were being heroic. The morning after fighting off the VC attack, Lieutenant Paul Leary joked grimly to Rose, “All I want is the Combat Infantryman’s Badge.” Rose added, “Americans in Vietnam are ineligible because they are theoretically not fighting.”

Two years later as the first American combat forces entered Vietnam, faith in the American mission was still evident in the Post. In a 1965 column, contributor Stewart Alsop wrote his own tribute to another advisor, Captain Robert Alhouse, who was advising a Vietnamese major in the small town Phu Hoa Dong.

Alsop observed the captain’s obvious affection for the locals: “What interested him and what he wanted to talk about was ‘his’ town, which he clearly loved already with a possessive love. To judge by the children, who crawled all over him like ants — he would occasionally brush them off, but they would climb back on — his affection is reciprocated. … He is determined to hold ‘his’ town against the surrounding Communists, and he has no doubt at all that the thing can be done.”

Another American soldier, Sgt. Thomas Alfinito, told Alsop the South Vietnamese soldiers were “damn good fighters and damn fine men. … We just … can’t let them down.”

“The honor of the United States has been committed by three presidents,” Alsop continued, “to the proposition that those ‘damn fine men’ who have fought the Communists so long and so bloodily — as well as the children who crawl like ants over Captain Alhouse — shall not become subjects of the Communist empire. It is impossible to see at all clearly how this war might be won. But, whatever the cost, we cannot permit it to be lost — not unless the United States is willing to accept dishonor as well as defeat.”

If America was disappointed in the outcome of the Vietnam War, it might be because the country entered the conflict with high expectations. In the years following World War II, the U.S. was still the most powerful nation of the free world. Americans could have easily assumed that victory would quickly follow their entry into Vietnam. Perhaps the failure of the mission to save South Vietnam seems inevitable 50 years later. But it wasn’t obvious in a time when the country still seemed the invincible champion of independent nations.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

The author shows bias in not identifying the presidents conducting the Vietnam War. Specifically not mentioning that John F. Kennedy started the first US combat troupe involvement by landing 14,000 combat troupes. In reading the morning newspaper, I remember how shocked I was, and how I foresaw only disaster. As a history buff, the result was historically forecast.

This is another excellent feature Jeff. I agree in feeling the post World War II years of optimism and feeling invincible contributed to most Americans’ feeling in 1963 this was doing the right thing, and perhaps, we even owed doing what we thought was a good deed back then for a country and people in need, having NO idea the horrors this involvement would unleash in the coming years of the ’60s and early ’70s. Most probably thought at first it would be fairly easy and quick.

Owning this very issue, I can honestly say the POST was cutting-edge with this cover and report on Vietnam. I dare say it’s two main competitors (LIFE and Look magazines) had not done anything quite like it as far as I know, being familiar with all 3 of this era, when I was older. I was only 5 going on 6 when this issue was new.

It’s a good example of how the magazine changed during the most turbulent years after World War II for both the country and the POST itself, resulting in some of the best and most fascinating issues of the entire 1900’s.

For a long time I know that issues of these years were not appreciated, and even frowned upon compared with 1961 and earlier as products of the older version’s declining years. While this may have been true economically, today they are being appreciated for the GREAT issues they were and are on the POST’s website, in past and current features like this. If these issues could talk, they’d thank you for referencing them for both their covers and content, making them part of the present day POST family on this site and in enriching current magazines themselves, giving them the long alluded respect that they are entitled to.