On this day in 1947, the CIA was established by the U.S. National Security Act. Seventy years later, America still can’t quite make up its mind about the Central Intelligence Agency. Does it serve the country or its own agenda?

The agency’s declared mission is to monitor “foreign threats to our citizens, infrastructure, and allies.” It is understandably reluctant to publicize much of its work, but a few years ago it posted several accomplishments on its website. They included identifying terrorist groups and assessing their capabilities, controlling the spread of weapons of mass destruction, gathering intelligence on Russia’s unpredictable government and economy, and destroying international drug trafficking.

No one can deny that the CIA played important role in helping the U.S. wage the Cold War. Even the Russians credit the agency with preventing the spread of communism into western Europe.

If only the agency’s record was all so positive. Unfortunately, the CIA has had some memorable failures as well, such as arming the Mujahideen in Afghanistan. It seemed a good idea when these Muslim fighters pushed the Soviet Union out of their country. It seemed a very bad idea when they re-formed as al-Qaeda and ISIS.

The Post became as fascinated by the CIA as the rest of America and published several articles about the agency throughout the 1960s.

The CIA Is Getting Out of Hand

In “The CIA Is Getting Out of Hand” from the January 4, 1964, issue of the Post, Senator Eugene McCarthy pointed out other jobs the CIA wouldn’t be bragging about. They included engineering the overthrow of the governments of Laos, Iran, and Guatemala. (Years later, critics would also place the responsibility for toppling the Chilean government in 1973 on the CIA.) He also mentioned the CIA’s botched Cuban coup at the Bay of Pigs.

The agency lacked any accountability, McCarthy wrote, and its activities sometimes ran counter to stated American policy. It was the CIA, he added, that was telling the president that South Vietnam, with U.S. support, could defeat the communist forces and remain an independent republic. They stuck by that opinion for years while America poured lives and fortunes into the war.

To rein in the agency, McCarthy called for a congressional committee to supervise its actions. That committee — the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence — was eventually established in 1976.

I’m Glad the CIA Is Immoral

But that oversight was still in the future when Thomas Braden wrote “I’m Glad the CIA Is Immoral” in the May 20, 1967, issue of the Post. He had worked with the agency to counter Soviet propaganda. Through covert operations, he set up programs that would shift the political alignments in labor, arts, and student groups around the world away from the Soviets.

He acknowledged that the agency had purposely hidden these projects from public scrutiny. But if deception, misinformation, and propaganda were immoral, so what? The U.S. was engaged in a cold war with Soviet Russia, he wrote, and war was inherently “immoral, wrong and disgraceful.”

“The cold war was and is a war fought with ideas instead of bombs. And our country has had a clear-cut choice: Either we win the war or lose it.”

Letter from the CIA

The intelligence industry has always been associated with issues of right and wrong. It has also been associated with glamour and intrigue.

In 1968, journalist Anne Chamberlin set out to discover if the CIA was as fascinating as she thought. In “Letter from the CIA,” she reports that the agency flatly turned down her request for a tour or an interview. When she decided to just show up anyway, she found America’s spy headquarters was — surprise!— a lot like other Washington bureaucratic offices.

I asked where I could find the man who had asked me not to come and was quickly escorted to a sort of reception room, with government leather couches, magazines on the tables and a desk presided over by a cheerful lady who asked me to fill in a pink form. It asked who I was, who employs me and whom I wanted to see. Then I was issued a large numbered badge and turned over to a young woman who led me to the office of my reluctant host.

Chamberlin eventually got access to the man she had been trying to see, but learned little other than, like any agency, the CIA had budget woes, too.

Whether you love or hate the agency, you can expect to hear more about it in the coming years, as intelligence, not firepower, becomes the first line of our national defense.

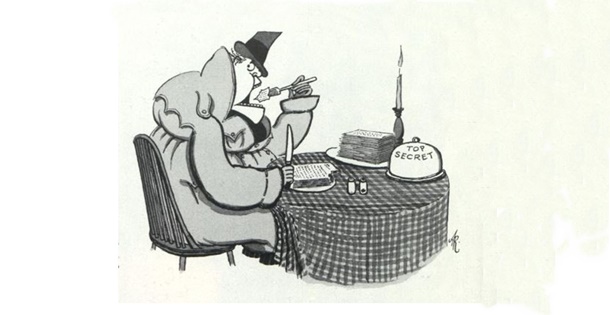

Featured image: Illustration by Arnold Roth for “Letter from the CIA” by Anne Chamberlin, from the March 23, 1968, issue of the Post.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

It’s good to read the Post was keeping tabs on the CIA in the mid & late ’60s as these interesting articles show. Immoral, getting out of hand, being asleep at the switch. 30+ years later, 9/11 may have been the result.

The lack of similar attacks thwarted in the 16 years since may also be a positive result of their staying on top of things as well. The daily drama with President Trump isn’t heping, but it’s no excuse for them not to remain laser focused.

9/11 was one horrible wake up call, I’d say! The March 1993 World Trade Center tragedy should have BEEN the wake up call if we HAD to have one, and we may not have had 9/11 eight years later.

It might have helped too if Clinton, the FBI and CIA were all on the same page. Congress was/is useless, of course. Living high on the hog at our expense sums them up in one sentence, and always will unfortunately.

Bill’s Monica drama in 1998-’99 surely helped Osama bin Laden and cohorts carry out this country’s worst tragedy since Pearl Harbor. That President was virtually useless from that point forward, unfortunately. How useful he was before that (in light of 9/11) remains ambiguous today, truthfully.

If nothing else, the CIA can be on top of terrorist threats foreign and domestic, stop them in their tracks, we’ll be able to live with their faults otherwise to a much greater degree. Being asleep at the switch though, ’90s style, ain’t one of them.