General Ulysses Grant emerged from the Civil War almost as popular as President Lincoln. So it wasn’t surprising that the Republicans nominated him for president, or that the country voted him into office.

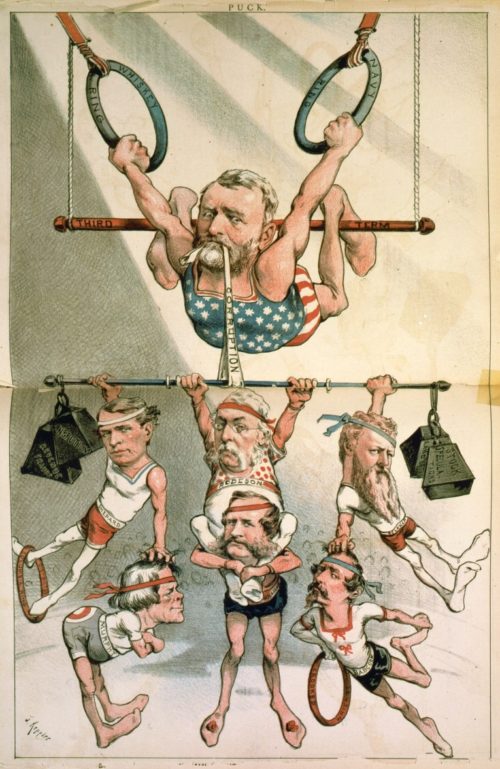

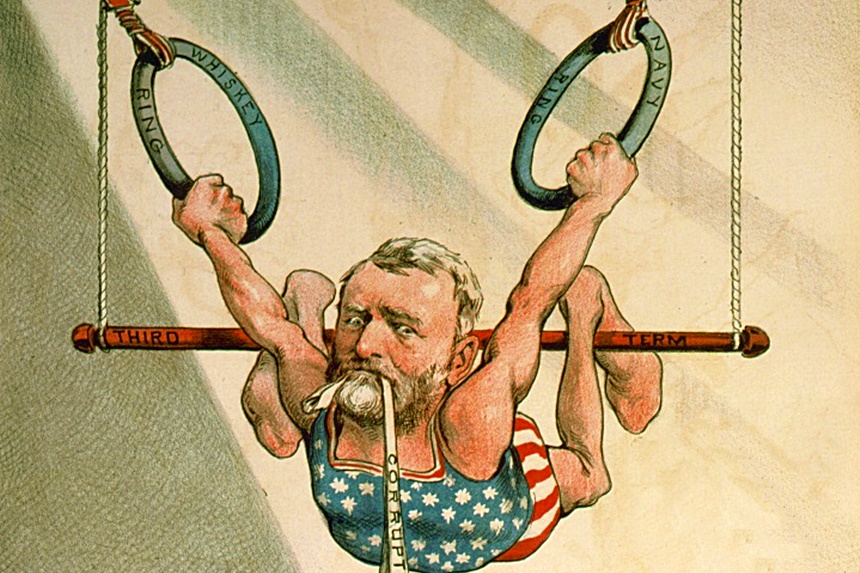

Unfortunately, Grant’s military skills didn’t work in the White House. He made several serious errors of judgment, and his presidency was marred by repeated scandals.

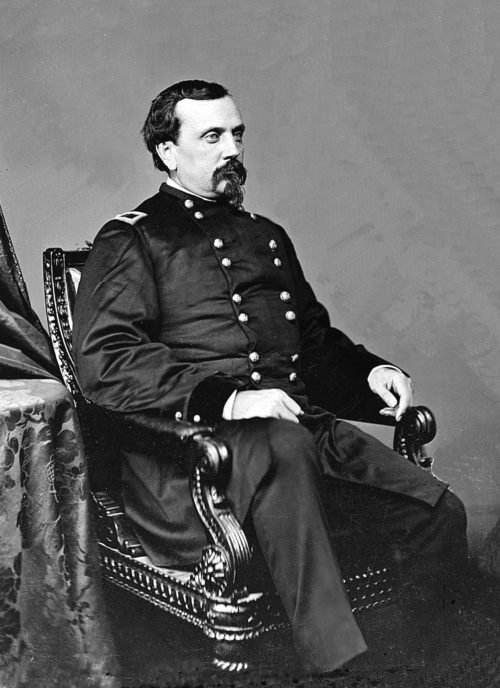

One of the biggest took place in the mid 1870s, when Treasury Secretary Benjamin Bristow learned of a widespread conspiracy to defraud the government.

Whiskey distillers were underreporting to the government how much whiskey they produced to avoid paying excise taxes of 70 cents per gallon. The distillers gave their bottles the appearance of legitimacy by applying excise stamps they obtained from crooked revenue agents in return for bribes. In this way, the “Whiskey Ring,” as it was called, avoided paying $2 million in taxes (the equivalent of $88 million today). Members of the ring included distillers and revenue officers, all the way up to clerks in the Washington Revenue Department.

Politicians had originally averted their gaze from the scam because it was raising funds for the Republican party, but soon it was working solely for its members’ profit.

By the time Secretary Bristow learned of the conspiracy, it had spread from Missouri into Wisconsin, Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, and Louisiana. On May 13, 1875, undercover revenue agents launched raids on these locations. Out of the subsequent arrests came 350 indictments of distillers and government officials.

Early intelligence led Bristow to believe the conspiracy reached into the upper circles of Grant’s administration.

Grant was determined to clean out his administration. He said, “Let no man escape.” Recognizing that unknown, high-ranking officials might try to block the investigation, Grant appointed the first special prosecutor: John Henderson, a former senator and longtime critic of the Grant administration. As special counsel, he would be able to pursue his inquiries outside of the Treasury Department.

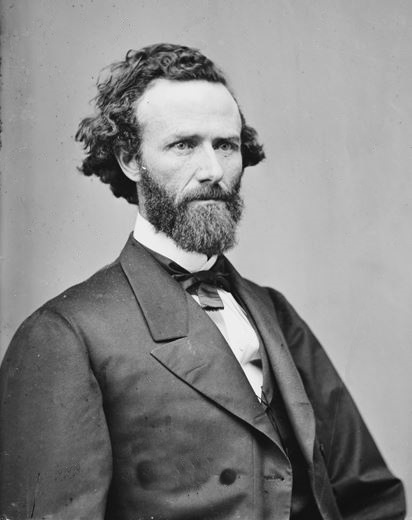

The investigation eventually identified two key figures in the Whiskey Ring: John D. McDonald, head of the revenue office in St. Louis, and Orville Babcock, who’d been Grant’s aide de camp during the war. Babcock was now Grant’s personal secretary. He interacted with the president every day and influenced who Grant saw, promoted, and trusted.

The evidence against McDonald was strong and he was soon convicted. But Babcock proved more slippery. He was able to convince Grant of his innocence, even after he was caught telegraphing a warning to a crooked revenue agent. Babcock went further, persuading Grant that special prosecutor Henderson had a hidden political agenda. He was trying to weaken Grant’s administration, the secretary said. Much of Babcock’s evidence was invented, but he brought to Grant’s attention an actual quote from Henderson. Addressing a jury in the trial of a ring member, he named Babcock as a conspiracy member and, carried away with his denunciation, hinted that even Grant’s innocence should be questioned.

It was too much for Grant. Just 10 days before Babcock was due in court, Grant ordered Henderson to stop giving immunity to suspects in return for evidence. This directive tied the prosecutor’s hands. Without immunity, distillers wouldn’t testify, and he couldn’t get the evidence he needed to convict Babcock.

Grant then took the unprecedented step of giving a deposition regarding Babcock’s honesty. Under the supervision of the Supreme Court’s Chief Justice, Grant stated, “I have always had great confidence in [Babcock’s] integrity and his efficiency. I have never learned anything that would shake that confidence.” Asked about some of Babcock’s questionable activities, Grant, who had a good memory, repeatedly said he couldn’t remember the incidents. But he could recall several instances of Babcock’s outstanding service.

When Grant’s deposition was read in the courtroom, it cut the ground out from under the prosecution. Jurors readily believed the president’s testament to his secretary. Babcock soon walked, exonerated, out of the court room.

Within two months, he was walking back into another court, this time accused of skimming money from construction projects in Washington. Again, he was acquitted. He was also indicted for involvement in a conspiracy to frame an enemy for a safe burglary. He was ultimately exonerated.

He might have been free, but Grant’s cabinet members were convinced of his guilt. They protested Babcock resuming his work in the White House. So Grant appointed him to be a lighthouse inspector instead. In 1884, Babcock met his end when he drowned while supervising an engineering project for the Moquito Inlet Lighthouse in Florida.

Grant’s loyalty to Babcock isn’t hard to understand. The secretary had served with distinction in the Civil War and provided service to the general. In peacetime, he’d zealously protected Grant from his political enemies and given him good political advice. Except when it regarded whiskey taxes.

Scrupulously honest himself, Grant just couldn’t imagine the depths of dishonesty in others, particularly those close to him. He could be blindly loyal to staff members even as they were betraying him.

Perhaps it was this credulity that attracted so many crooks and scoundrels to his administration. And it was Grant’s loyalty that upset a special prosecutor’s case and enabled a crook to walk away, guilty but much richer.

Featured image: Library of Congress

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

This is 19th century Presidential outrage of the highest order, but I can see how it happened. Babcock did a lot for Grant over the years including the good political advice and political enemy protection. Grant allowed himself to be blind to what he should have seen though. The perfect storm for what happened here.

Babcock’s crimes though are pretty severe. I’m sure Grant’s cabinet members were quite pleased when he met his end prematurely, with the Florida drowning. Another case of where greed/money hastened a crook’s demise.