It was a Sunday — Sept. 2, 1945 — the day the representatives of Japan in their formal diplomatic attire and top hats came aboard the USS Missouri anchored in Tokyo Bay to sign the papers of surrender that ended World War II.

It was also a Sunday on December 7, 1941. I was in my room doing homework when my parents called me to the living room to hear the news. The Japanese had bombed a place in Hawaii called Pearl Harbor. When I reached school the next morning it was all the talk. And the spin, as we say today, was that we’d never lost a war. “Neither,” said our American History teacher, when we took our seats in his classroom, “have the Japanese.”

It was while we were in our American history class that President Franklin D. Roosevelt addressed a joint session of the United States Congress, the speech piped into our classroom via the public address system. So, instead of continuing our study of the lead-up to the Civil War, we heard the lead-in to ours: “Yesterday, December 7, a date which will live in infamy ….”

I was in my senior year, and at the senior class picnic that May the guys made splashy dives into the lake. I realized many of them would be off to the war, if not as soon as we turned in our caps and gowns, shortly afterward.

They would be but a few of the 16 million men who served — almost 500,000 of whom never returned.

I did not serve. I was 16 when I graduated, and female. And because I moved away shortly after graduation, I could not follow the guys from my class who did. Years later, during a chance encounter with a man who was familiar with my hometown, I learned that the guy who sat in front of me in French class had served and returned to marry the girl who sat on my left. A happy ending.

But I didn’t escape the toll.

One evening during my second year at Stephens Junior College, a girl on my floor had a dinner date with her hometown boyfriend, a Navy pilot who was about to be shipped out. It was policy whenever possible to send servicemen home for a short farewell visit before they shipped out; he had stopped to see her before returning to his base. The sparkle on her ring finger was no match for the stars in her eyes.

He was killed in action.

Beyond the formal notice in the local newspaper of sons and brothers, fathers and husbands serving, the front windows of houses displayed small, hand-size fabric symbols, white satin with red satin edges that hung from a braided thread. A blue star in the center signified a member of the family in service. A gold star signified their death.

It was not uncommon to see two, three, even four blue stars. Sometimes a blue (or two) and a gold.

I remember that notification of a death was made by telegram then. The Secretary of the Army … or the Secretary of the Navy Regrets to Inform You that …. One year, shortly before the war ended, my parents and I went down to the small dining room in our apartment building for Mother’s Day dinner. We were surprised that our former next door neighbors were not there. The waitress then told us they’d received a telegram the previous day — their son, whom we’d met when he was home on leave and I’d played bridge with before he shipped out, had been killed in the Philippines. I’m still surprised telegrams went out the day before Mother’s Day.

The recent ceremonies marking the 75th Anniversary of D-Day showed the rows upon rows and still more rows of symmetrical white crosses and Stars of David in the American military cemetery overlooking Omaha Beach. And more rows and rows of white crosses and Stars of David stretch out seemingly forever at the American military cemetery in Belgium, “home” to the town of Bastogne and the Battle of the Bulge — 57 acres, 7,987 dead.

World War II did not simply make casualties a part of our lives, it permeated our lives. It was always there. Everywhere. Like the weather.

Posters told us what to do. Make things last. Use It Up — Wear It Out — Make It Do.

They told us what not to do. Be careless in our conversation. Loose Lips Might Sink Ships

They promoted family gardening. YOUR VICTORY GARDEN Counts More Than Ever!

Comments became rallying cries, songs, and posters. A priest at Pearl Harbor: “Praise the Lord and pass the ammunition.” A pilot with a shot up plane: “Comin’ in on a wing and a prayer.”

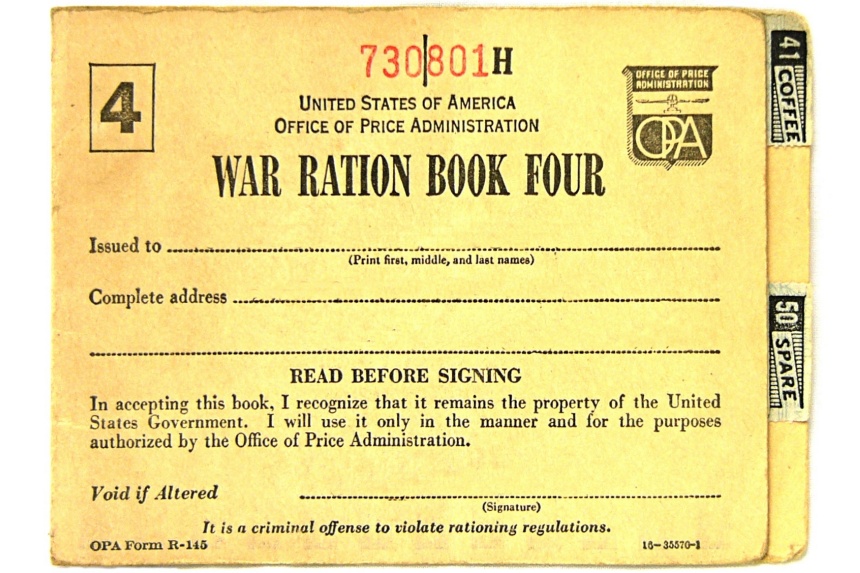

Rationing restricted driving — cars had small, square, block-letter stickers in the lower right corner of the windshield to show the level of gasoline the owner could buy. The lowest was A, for the general public — four gallons a week. C went to those who drove a lot, such as doctors, who made house calls in those days. All enforced by books of rationing stamps.

Rationing restricted sugar, butter, and meat, too. My mother, my father, and I were each issued a ration book — a booklet with stapled pages of stamps, first cousins to U.S. Postage stamps. We had to tear them out and hand them in when buying rationed items. I had to take my ration book when I went off to college and turn it in, as did the other girls, because we got our meals in the dormitory dining rooms. I took it home for Christmas, brought it back after the holidays, and took it home for summer vacation.

The war took its toll on what we wore. To save fabric, the cuffs on men’s trousers were eliminated and women’s skirts were shortened to the knee — they had been mid-calf length — and were straight. As in no pleats or folds, straight, straight, straighter.

And the stockings we wore — pairs, not pantyhose — were suddenly back to rayon after the wondrous nylon that came in just before the war. Light and durable, nylon was needed for parachutes. Because stockings then had seams up the back, I was not only careful when putting them on to have them straight, I would often look back over my shoulder during the day to be sure they were still straight. (You’ll see women in old ’40s movies doing this.)

Servicemen were also the priority with things that were the simple pleasures of our lives: Cokes and cigarettes. Cokes were extremely popular then, too, and came in glass bottles. No cans. Shaped bottles with metal caps, if you could find one. And cigarettes became so hard to get a pack was a treasure.

But I did once see a carton of cigarettes. A carton of cigarettes! I most surely did. During my first weeks at the Chicago Daily News. I was a copygirl — apparently the first, as the war had siphoned off almost all the guys — and I had just been assigned to the city desk. One day the receptionist brought in a carton of cigarettes that someone had sent the city editor. (As if I hadn’t known before he was important.)

One of my duties was to call the U.S. Weather Bureau before each deadline and get the temperatures for each hour since the last. I put them on a piece of paper I turned in to the city desk, which sent it along to the copy desk, and eventually down to the composing room to update the day’s weather report. No cold fronts moving in or out. Just a small box in the top corner of the front page, about the size of a commemorative postage stamp. It would have a simple heading. RAIN. COLD. SUNNY. Perhaps a word or two expanding on that. And a list of the hourly temperatures, which I duly updated.

We printed nothing that might help the enemy determine weather patterns, what the weather might be in the days to to come. That could be invaluable. Indeed, a slight break in the stormy weather that Allied meteorologists picked up on was crucial in the decision as to whether D-Day — originally scheduled for June 5 — should be a “go” on June 6.

The weather would still not be ideal, but the massive invasion was on hold — 5,000 ships in ports or just off the coast of England, thousands upon thousands of men aboard the transports or naval vessels. The break in the weather was not much of a break, but it was a break the chief meteorologist to the Supreme Allied Command foresaw from readings he got from a weather station in the North Sea. And if it they did not go June 6, they could not postpone again, they would have to wait two weeks, perhaps a month, for the right combination of moon and tides.

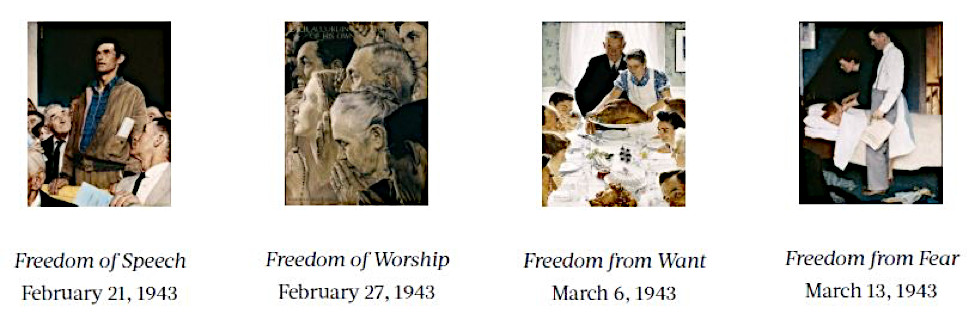

World War II, widely considered the defining event of the 20th Century, was a mosaic of such challenges. Battlefield decisions. Wartime images.

I remember the sailor I saw when I had to leave school and go home for a medical emergency, serious enough to warrant the trip when travel — mostly by train then — was restricted. In moving from my car to the dining car, I had to pass through the foyer-like area that links one car to another, where people board and leave. Sitting in one corner, knees drawn up, round white cap at an angle — head bent so low his chin almost touched his chest — was this sailor, a huge, Navy-issue white duffel bag to one side.

Heading home before shipping out? Returning to base?

I didn’t know then. I don’t know now.

I didn’t even know why he was sitting out there, because I remember any number of seats in the coach car I’d just come through.

But if Norman Rockwell had seen him, he’d have ended up on a cover of The Saturday Evening Post.

Featured image: Shutterstock.com.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

You really captured it. Wars back then were felt at home, for everyone sacrificed. Thank you for sharing this bit of history.

Thank you Ms. Lauder, for sharing this personal account of your own life during World War II, and in such detail. I can tell those years left a permanent imprint on you. I’m so sorry you had to go through the hardships, pain and suffering you did, but know you did what you had to do, never feeling sorry for yourself.

I’m very proud of you being the first copygirl for the Chicago Daily News! Your job was extremely important, and you were great at it! Your description of the sacrifices you and your generation made should never be forgotten. I found the recent 75th Anniversary of D-Day to be VERY humbling and touching.

There’s no question World War ll was the defining event of the 20th century, and so many appreciate your generation, ‘The Greatest Generation’ now more than ever!! Having been born well after World War ll myself, I (frankly) shudder in shame at the thought of how the Woodstock generation trashed your generation’s ideals and accomplishments 50 years ago. If it’s any consolation, I know quite a few of those people who now appreciate your wonderful generation very much, looking back upon their youth often in horror now. “What were we thinking?!” Indeed. There are people and events that have changed our lives for the better and for the worse, unfortunately.

As far as the sailor you describe on the train in your final paragraphs, I also think Norman Rockwell would have wanted to capture that image for a Post cover. The painting would be one for the reader to ponder and wonder as to where he was coming from, or going to. Many Post covers left the reader to draw his or her own conclusions.

Thank you again so much for taking the time and effort to write this personal essay. You’re a wonderful woman, and a wonderful American woman. God bless you!