On July 29th, coal miners in southeastern Kentucky gained national attention when they began an ongoing protest using an old tactic.

The miners — former employees of Blackjewel LLC before they were laid off in early July — took to the railroad tracks to block an outgoing train loaded with coal. “No Pay We Stay,” reads one of their signs. The workers received paychecks that bounced (or no pay at all) for their last weeks of work since Blackjewel went under.

The news of the persistent Kentucky coal miners reads like a headline of yesteryear, when “the labor question” was a phrase uttered by analysts and politicians at the turn of the century to hint at the growing divide between workers and bosses. The possibility of unrest and anarchy from prolonged strikes demanded that the question be answered. Toward the middle of the century, it seemed that it was; now, the labor question is back.

The train-blocking coal miners in Kentucky aren’t the only recent instance of collective action hinting at a new labor movement.

In January, during the longest federal government shutdown in U.S. history, the president of the Association of Flight Attendants, Sara Nelson, publicly called for a general strike in support of the federal airport workers who had been working without pay for a month. Days later, air traffic controllers began calling in sick, causing flight delays in New York, Miami, and Philadelphia, among others. The government shutdown ended, owing largely to the prospect of lost economic growth from grounded planes.

Last year, teacher strikes and walkouts in West Virginia, Oklahoma, California, Kentucky, and more states made 2018 the “biggest year for worker protest in a generation,” according to The Washington Post. Teachers’ unions have led rallies and collective action across the country to call for better wages and higher funding for public schools.

The labor question could yield any of a number of answers: increased union membership, massive strikes, corporate pushback, policy proposals like minimum wage increases or public safety nets, etc. It’s an imbalance — often referred to as income inequality — that seeks to right itself through some means, sometimes political.

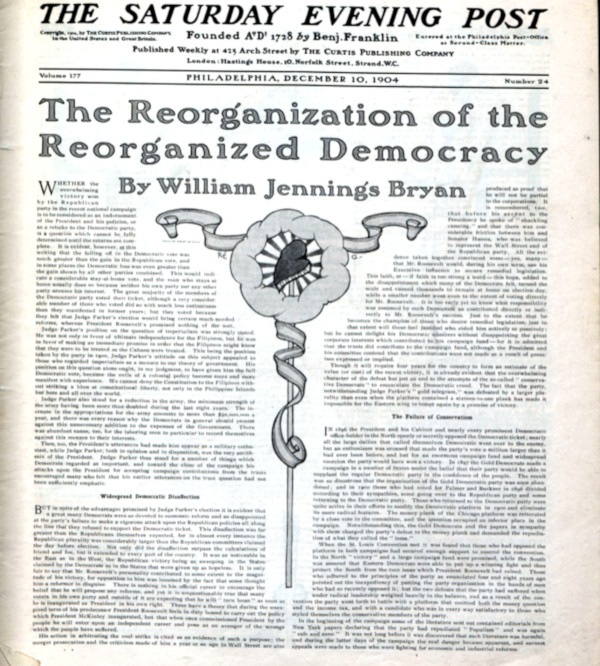

At the turn of the 20th century, the relationship between labor and politics was still uncertain. William Jennings Bryan wrote in this magazine, in 1904, shortly after Theodore Roosevelt won his second term:

The labor question is growing in importance. The manufacturers are organizing to fight the legislation asked for by the wage-earners. The tendency of this is necessarily to widen the gulf between labor and capital … The Republican Administration must meet this problem. If it takes the side of the laboring men it will alienate those corporate influences which have for some years dominated the Republican party; if it fails to do anything, the growing resentment among the laboring men will manifest itself at the polls. (“The Reorganization of the Reorganized Democracy” December 10, 1904)

Bryan’s insistence that manufacturers’ efforts to fight labor’s demands would “widen the gulf between labor and capital” seemed to have borne out. By 1929 — just before the Great Depression — the 0.1 percent of wealthiest individuals in America held 28 percent of wealth. Bryan was mostly on the side of labor, or at least arbitration, but at the time it was unclear exactly how labor should engage with the two major political parties (if not make one of its own). Labor leaned toward the Democrats, but sought to maintain its leveraging power by playing all sides throughout the Progressive Era.

Sometimes, labor’s call for political action did take the form of a party — and quite successfully. Patrick Henry McCarthy became mayor of San Francisco that way in 1910. An iron-fisted leader of the Building Trades Council there, McCarthy was a member of the Union Labor Party who “sees red about fourteen times a day,” according to Post editors in 1911.

When the millmen of his BTC struck for an eight-hour day and a pay raise and were locked out by the mills, McCarthy gathered a board of trustees from the union and opened their own planing mill. They were able to cut out the reluctant mill from business until they agreed to come back to the table.

Although he never lost opportunity and hated peace, according to the Post, “no matter what may be said concerning his domination over labor and the labor vote, there has been little labor disturbance in San Francisco in McCarthy’s line — the building trades — since he took hold.” The Union Labor Party dissolved shortly after McCarthy’s term.

The labor movement still took hold, however. Based on the best available labor statistics, union membership of all employed workers in the U.S. jumped from 7.5 percent in 1930 to 28.3 percent in 1954. After FDR’s New Deal programs, labor became bound to the Democratic Party for decades to come. Then, in the 1970s, union membership began to drop, and it never stopped sinking. Last year, union membership among wage and salary workers was 10.5 percent, almost half of what it was 1983, when the Bureau of Labor Statistics began recording such data.

Just as unions have diminished, the wealth gap has risen once again to levels seen during the Jazz Age. A recent Princeton study found that “unions appear to be associated with higher income and that association is stable over time.” The difference in income is 10 to 20 percent, and that correlation goes back to 1936. Much has contributed to the decline of union power, like the right-to-work laws in place in 27 states, a changing environment for labor, and ever-changing public opinion.

On the public opinion front, however, labor appears to be making humble gains. In a Gallup poll last year, 62 percent of people approved of unions, the highest number since the ’90s. Pew Research showed similar results, along with 75 percent approval rating for unions from people ages 18-29.

That could be part of the reason that the coal miners in Kentucky have received such staunch support from politicians and community members. Even if they aren’t acting on behalf of a union, the Blackjewel workers are committing to direct action in the same tradition as many before them. When the labor question arises, the miners — and many other workers — are compelled to find their own answers.

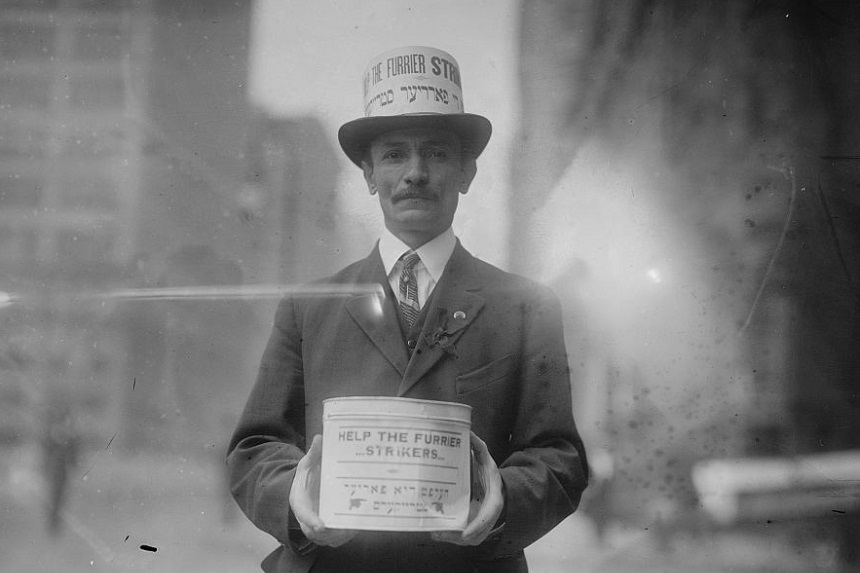

Featured image: Library of Congress, George Grantham Bain Collection, 1915

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now