Like magic, seemingly, you scroll past an advertisement for the perfect product. Something you’ve been looking for (or dreaming of?) for as long as you can remember. But how did they — the big tech sorcerers — know?

Data, of course. Your age, interests, location, and browsing behavior are all fed into algorithms to present you with advertisements that align with your lifestyle. Ever since the internet became a who’s who of everyone, tech companies have been fine-tuning this practice, But predicting which products will most successfully part you from your money — targeted advertising — has been around for as long as the post office.

Whereas snippets of you are now stored around the web, the “cloud” of yesteryear consisted of the many filing rooms of mailing list houses. These companies kept careful records of public lists as well as cabinets of cards denoting private lists they could rent out. The system wasn’t as robust as it is today, but it formed some lasting models that proved how effective advertising can be when it’s put in front of the right people.

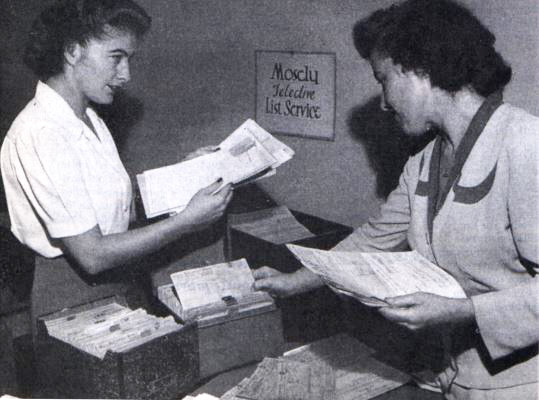

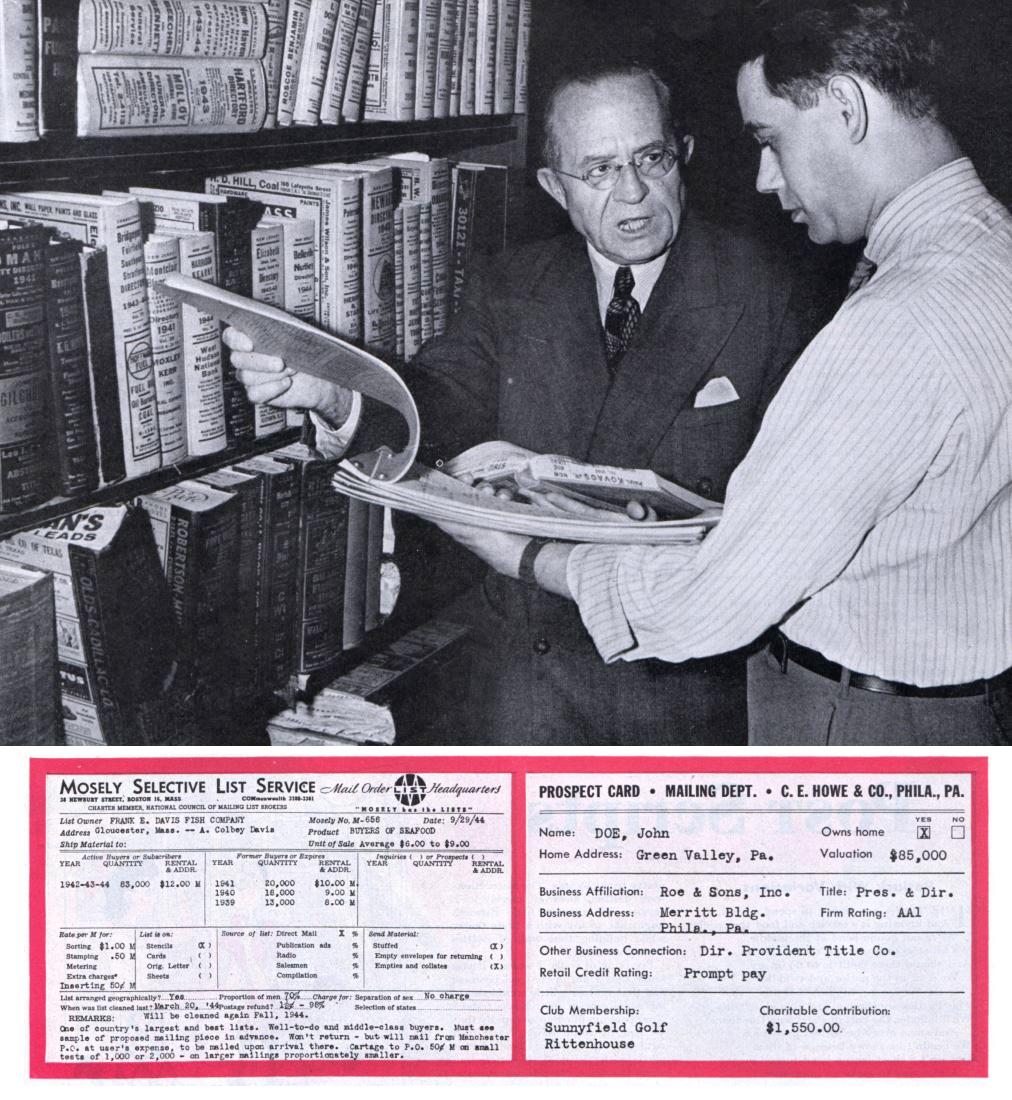

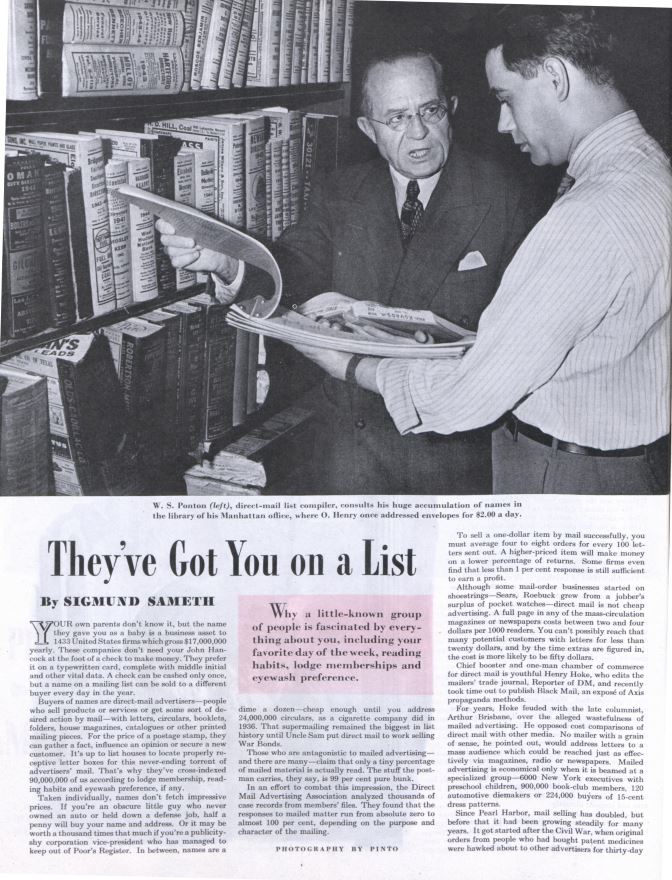

During World War II, mailing list companies like W.S. Ponton and Mosely Selective List Service realized that direct mail advertising was becoming a significant industry. From 1941 to 1944, sales by mail in the U.S. doubled after having seen steady growth, according to “They’ve Got You on a List,” a story about mailing list houses published in this magazine in 1944. Ponton’s and Mosely’s firms boasted that they could rent out lists of potentially interested consumers for a litany of goods and services, from seafood to cesspool cleaning to pincushions.

Their list houses had to be maintained with up-to-date names and addresses. So long as these firms could keep up with the filing, they could traffic in all sorts of lists of varying specifications. According to the Post,

From your daily assortment of mail, you can learn how much money people think you have. If insurance companies write to you suggesting policies under $5,000, your name appears only on low-income bracket lists. Circulars describing haberdashery and moderately priced food specialties show that you are pigeonholed as a $5,000-a-year man … If you receive letters about art-collection dispersals and solicitations for philanthropies and endowments, you are worth $100,000 a year — or else are putting up a terrific front.

It wasn’t always common knowledge that advertising products and services directly to consumers based on hyper-specific trait-gathering was a winning strategy. In the heyday of broadcast and print media, big advertising firms often rejected the premise of “junk mail” in favor of flashy campaigns in magazines and on primetime TV. Historian Andrew Case, in his paper in History of Retailing and Consumption, writes that direct mail’s influence has been woefully ignored in accounts of American marketing of the twentieth century: “Historians have explored postal systems as a means of circulating news and information, but the ways in which the mailbox allowed marketers to carve out specific audiences of consumers and citizens in the twentieth century is less well-known.” The disposable nature of direct mail didn’t help to preserve its legacy, either.

Nevertheless, the arithmetic of direct mail advertising worked out splendidly for salespeople and list-keepers alike. For publishers or jewelers or makers of nose hair trimmers, a list of customers could serve as a source of pure profit.

Any company or organization that kept a list of names and addresses found — with the help of “list brokers” — they could rent out these lists to other firms for one-time use. A merchandiser or nonprofit could rent out a list of “Buyers of Fountain Pens” or “Donors to a Liberal Cause” for about 20 dollars per 1,000 names. To insure the buyer was using the list only once, the list-keeper would either address and mail the pieces themselves or include on the list some dummy names that would alert them to any double-dealing. First, a buyer could test it out with around 3,000 names. If the list seemed promising, they might mail out to 100,000 or 500,000. Minus the list broker’s cut, it was a tidy profit for very little labor.

Calvin Trillin wrote about list brokers in The New Yorker in 1966, paying attention to their knack for turning ordinary data and interactions into profit: “A broker or a compiler of mailing lists … can see a potential source of profit where others see only a list of names. And he can see a list of names where others see only a method of licensing automobiles or delivering magazines or giving away free recipe booklets.” According to industry data, spending on direct mail marketing had risen nearly tenfold since the ’40s, to $2.4 billion. The number closely resembled television advertising expenditures in the ’60s.

The next step for the direct mail industry was to realize that it could be useful to sell more than gourmet cheese and sex books; it could also sell political candidates.

The foremost figure in bringing direct mail strategies to political campaigns was Richard Viguerie. In the ’60s, consultants convinced the Republican National Committee to try direct mail, using lists from buyers of Kozak Drywash and plastic car covers to reach donors, but Viguerie took right-wing direct mail to another level. Having worked with the National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation and the NRA, Viguerie used his direct mail consulting firm to help conservative candidates build giant donor bases that could act as fundraising machines.

He worked with Barry Goldwater in 1964 and George Wallace in the ’70s. (Though Wallace was running for the Democratic Party, Viguerie admitted they saw eye to eye on most issues.) When George McGovern approached the direct mail guru in 1967, Viguerie referred him to Morris Dees, another direct mail man who helped the outsider win the 1972 Democratic candidacy. Though Viguerie couldn’t bring Wallace across the finish line in 1976, he set the standard for grassroots fundraising via clever mailing. Viguerie obtained lists of Americans who loved sports and hated pornography, getting rolls of boat owners, businessmen, and even the mailing list of The Saturday Evening Post. The content of the mailers was important, too. He found a successful strategy for getting donors was to stir up fear against a simple issue, like communism or busing. “You see, in an ideological cause like this, people give money not to win friends, but to defeat enemies,” Viguerie told New York Magazine in 1975. The article states that he probably had “the best political solicitation apparatus in the republic.”

Viguerie’s direct mailing efforts were replicated in political races around the country, and a new standard for political discourse was born in third-class mail. From 1981 to 1999, Karl Rove ran a direct mail business that helped hundreds of candidates get elected. Historian Andrew Case says the capacity for A/B testing in direct mail — the practice of using alternative messages to hone a campaign — played a huge role in its success over the decades. “Much of the political advertising that we now deal with was tested and refined over time in the direct marketplace,” he says.

Direct mail brokers learned that, like an algorithm, these mailers strengthened a campaign by providing feedback data — and, of course, money — that could inform future strategies. Frequent mailings could actually improve lists and condition donors instead of wearing them out.

“Junk mail” has earned a dubious reputation over the years. Credit card offerings with deceptive packaging and political mailers covered with outright lies has cast the industry in a similar light as the early years of phony miracle medicines and other obvious grifts. No one can say it doesn’t work, though. Even as tech giants like Facebook and Google dominate the advertising industry, direct mail still plays a (declining) role. According to USPS, response rates for direct mail have improved in the new millennium. Other sources claim they’ve risen dramatically just in the last decade. Destined for the garbage as it may be, junk mail almost always passes under the eyes of its recipients. The physicality of direct mail demands attention in a way other advertisements cannot.

Presciently, Calvin Trillin wrote, in 1966, that “Some people in the trade believe that computerization will eventually result in great master lists of all magazine readers and all gadget buyers.” The pause-giving scope of targeted marketing online reveals itself from time to time, like when whistleblowers make claims of massive, unaccountable data troves or when studies show that personalized ads perpetuate racial biases. The ad men of Madison Avenue may have laughed off direct mail in the mid-century, but it proved that marketing works well when a brand can pick its own audience. Robust algorithms are now trained to dissect our own psychology better than we can ourselves, and they can sell us products and ideas without even paying for a third-class stamp.

Featured image: The Saturday Evening Post, by Pinto

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Well, I am not saying I am influenced by Adds but I have got to the point where if I could turn off ALL adds I would.

for T.V I mainly watch pre-recorded Programs and SKIP through the Adds and others where there are no Adds. BBC and Sky films is great.

I have add blockers set up on my computer so that stops “some” of it. Because I am one f the old generation (61) I have never used twitter, and I basically stopped using facebook a few years ago (Probably use it a couple of times a year).

Watsapp, are there Adverts? Cannot remember seeing any.

After all just because I bought a hard drive, or a hair dryer does not mean i need to buy another one.

If I want something I will look for and buy it otherwise do NOT bother me!

Thanks for this interesting report on junk-mail and its origins. The computer/internet has brought it high tech, and therefore more “in your face” than in the 20th century, but it was all in place then waiting for that revolution.

Some of it is okay even though I know it’s via ‘Big Brother’. For example eBay remembers the John Lennon (psychedelic cover by Richard Avedon) issue of LOOK magazine I bought in 2009 for $35. It was in excellent condition and that was a great price, trust me. I still get pop-ups for that issue even now, except they’re in fair-poor condition for $175-$300. No thank you.

Its not all bad. eBay found a ’57 Chevy print ad they saw me looking for, found, and presented. For collectibles I much prefer eBay, Amazon for the more ordinary. Good ‘ying and yang’ like the 99 cents store and The Dollar Tree. Basically the junk mail that bugs me most are the weekly supermarket ads that clog up my mailbox. I’ll remove the ones for Trader Joe’s and Sprouts however. The rest go right into the recycle bin.

Still, I welcome 0% balance transfer ads for 18 months from the legitimate banks. Sometimes ya just need to tap into that premier line when something unexpected happens and need extra money—immediately. I just don’t like having to pay it back with interest.