From its very beginning, the idea of federal assistance programs has troubled some Americans.

In the 1930s, people complained that the Works Progress Administration (WPA) programs were just paying workers to lean on shovels. And when the Aid to Dependent Children (ADC) program began in 1935, some were concerned that it would create a culture of dependency. Author of The Queen: The Forgotten Life of the American Myth Josh Levin notes that publications like Reader’s Digest and Look ran stories of women who’d swindled the welfare system to enrich themselves.

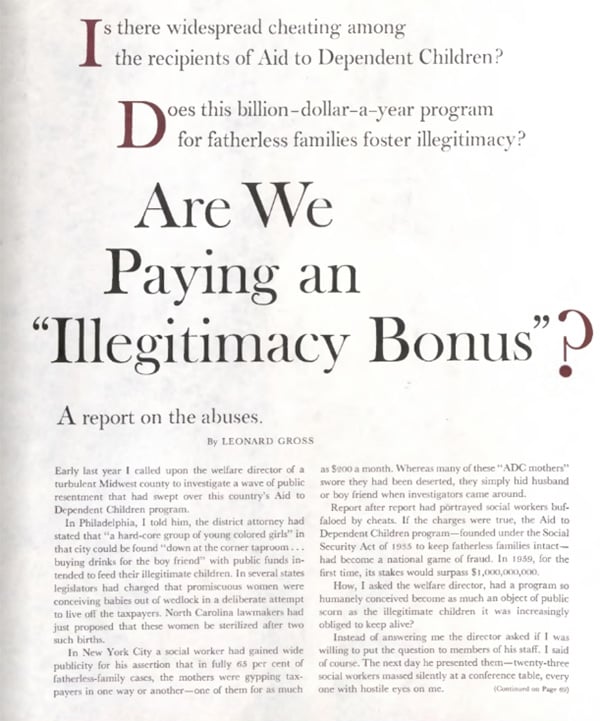

By 1960, writer Leonard Gross had reported on welfare corruption in The Saturday Evening Post. In “Are We Paying an Illegitimacy Bonus?” he reported that a social worker in New York claimed 65 percent of ADC recipients were cheating the system. In Philadelphia, a story was circulating that single mothers were giving their ADC support to their boyfriends. In North Carolina, it was claimed, a woman had refused to marry the father of her children because it would mean the end of her ADC checks. No one seemed to know her name, or the exact number of her children, though the total grew as the story aged. Officials at North Carolina’s Board of Public Welfare searched through their entire system looking for the woman. Ultimately, they concluded, she didn’t exist.

Determining how much social services fraud actually existed back then is nearly impossible. At the time, each state was responsible for determining what constituted fraud and how to prevent or prosecute it. In 1961, the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare finally issued federal guidelines concerning ADC fraud in response to press reports that “could neither be substantiated nor refuted.”

The 1960 Post article by Gross went on to say that legislators in several states believed women were conceiving children just to increase their assistance payments. He wrote that one state was considering the forced sterilization of unwed mothers with more than two children. (In fact, North Carolina actually did sterilize 7,000 women starting in the 1950s.)

Yet government numbers showed that mothers who legitimately qualified for ADC were being underserved. Of every 1000 American children in 1960, 79 were in need but only 30 received assistance.

In the many stories of welfare fraud, Gross said, social workers were portrayed as easily fooled or actually collaborating with cheating recipients. So he asked social workers what they knew about cheating in the welfare system. He was startled by their bitterness and frustration as they responded to the stories.

One angrily said, “We’re not out to hide frauds. We pay taxes too.” Another said, “We work long hours for little pay, sometimes at great physical risk — and this is the thanks we get.” A long-time social worker claimed that he’d worked 2,000 cases and uncovered just two cases of fraud.

These social workers’ experiences were not far from the norm. In 1958, Chicago had 20,000 mothers on support and 245 cases of fraud. In Boston, 175 cheaters were found among 4,600 cases. Nationally, the Bureau of Public Assistance determined the percentage of fraudulent claims was .09 percent.

No one denied welfare fraud existed. But the rumors led many to believe the system was enabling cheaters. Their assumptions were reinforced in 1974 when the Chicago Tribune reported the case of Linda Taylor, who was convicted of repeatedly defrauding several assistance programs.

Presidential candidate Ronald Reagan referred to her often in his 1976 campaign. She had received assistance under multiple names and addresses, he said. She’d obtained veterans benefits for four non-existent husbands. She drove a Cadillac, wore a fur coat, and bought steaks with food stamps. She was, he said, “welfare queen.”

She embodied the dishonesty and laziness that many believed were typical of welfare recipients. Angry taxpayers pressured their legislators to reduce funding for a system they believed was riddled with incompetence and fraud.

Acting on the assumed dishonesty in the system, President Clinton pledged to “end welfare as we have come to know it” in 1996. His Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity law changed ADC to the Temporary Assistance to Needy Families [TANF]. To prevent recipients from receiving a lifetime of benefits, TANF now capped assistance to a lifetime limit of five years.

The law also made the qualifications for receiving aid more stringent. And, most important, it dispersed assistance through block grants to states, which would provide matching funds. Now state officials could control who would receive federal assistance, including restricting the flow for political purposes.

As you might expect, the states’ levels of assistance vary. In California, for example, 66 percent of residents below the poverty line receive assistance. In Texas, the rate is 6 percent. In Mississippi, fewer than 2 percent of people who apply for TANF qualify.

Without a federal account of welfare fraud, it’s difficult to tell how well the new regulations are working.

A 2013 Atlantic article estimated the fraud rate in the TANF program would be comparable to that of unemployment insurance payments — less than 2 percent — and went on to point out that the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners says no business, however well run, can expect to be free of corruption; a typical business will lose 5 percent of its revenue to fraud every year.

In 2016, the Office of the Inspector General reported the rate at which food stamps — now the Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP) — were illegally being sold was 1.5 percent. Forbes reported the percentage of overall SNAP fraud that year was 0.9 percent.

While these may be small percentages, they still represent a disturbingly large amount of money stolen from taxpayers and the underprivileged.

Yet the TANF and SNAP program aren’t exceptionally mismanaged by government standards.

According to the Government Accountability Office, the total amount of improper payments paid by federal agencies in 2017 was $141 billion. The Defense Department has uncovered $150 billion of fraud in its defense contracts since the beginning of the Iraq war.

And while states may deny funds for residents, they have found their own uses for assistance block grants. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities reported in 2017 that states were only spending a little more than half of their combined federal and state dollars under TANF on core areas for which the grants were originally intended — basic assistance for families with children, child care for low-income families, and work-related activities or supports.

“A handful of states,” it said, “spend less than a quarter on these areas.” The remainder of the block grants were spent on things like administration and tax credits. No doubt welfare cheaters exist in discouraging numbers, but they’re not the only Americans gaming the system.

The suspicion toward people who use social safety net programs continues. In President Trump’s recent budget proposal, he suggested changes to the Social Security disability program that would potentially cut hundreds of thousands of recipients. As with so many other programs, one of the reasons for the change is to reduce fraud.

Featured image: Excerpt from a report on welfare fraud (Wikimedia Commons)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I’m always wary of comments that claim to know what is impossible, and make statements regarding ‘not a single person’. These arrogant assumptions are simply an opinion.

The investigators found little fraud, they didn’t judge the goodness or relevance of that fraud. The above comment is full of subtle fallacies.

I’m always wary of “study’s” that claim to report fraud. It is literally IMPOSSIBLE to report on fraud. I come from the part of society that heavily utilizes this aid and I can say from personal experience that: Not a single person has used them in compliance. Even individuals who were close friends of mine, not folks I would call “bad people”, would sell their EBT for a fraction of their value.

Even if the person doing the fraud isn’t a bad person, it doesn’t make the fraud less relevant.