Last summer’s Black Lives Matter protests and the more recent attack on the Capitol by white extremists have us grappling with how to move forward as a nation. Black novelists may be able to help us make sense of centuries of racial conflict and mistreatment through creative retellings of history. Can laying bare centuries-old wounds that continue to fester help us heal as a nation? How can fiction help us deal honestly with history? New novels by Black writers are taking readers on imaginative, often hellish journeys into the country’s past to better understand our present day relationship with racism.

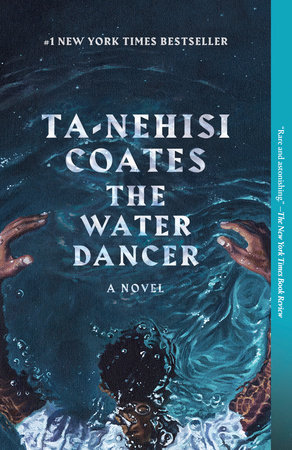

Best known for his non-fiction, Ta-Nehisi Coates, author of the National Book Award-winning Between the World and Me, sets his 2019 debut novel, The Water Dancer, on a plantation in antebellum Virginia. Coates has long argued that much of the country’s history is premised on forgetting. When he made the case for reparations to Congress in 2019 he called for Americans to be courageous enough to address the whole story of its past. So it’s not surprising he’s crafted a novel where the protagonist’s superpower lies in memory, on understanding the past. In this first novel he’s able to mix history with fantasy to go beyond the stubborn facts and figures he usually features in his writing as a journalist. As a novelist, he doesn’t need to let the facts get in the way of the story.

Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award-winning author Colson Whitehead has repeatedly reimagined history in novels like The Underground Railroad, where he invents an actual subterranean network of tracks and rail lines, transporting slaves out of bondage. Whitehead’s imagined railroad takes slaves on a frightening journey north, making stops along the way in various states, exposing the unique institutionalized evils of racism in each one. Yaa Gyasi’s debut novel, Homegoing, goes back even further in time. Tracing her own Ghanaian roots, Gyasi explores West Africa’s role in the slave trade and how that legacy continues to be felt today.

Pulitzer Prize winning novelist Edward P. Jones also explores the role that Blacks played in slavery, inserting himself into a maddening world of contradictions in 2003’s The Known World, about Black slave owners in Virginia. Though readers may find it hard to believe, historians say there is evidence that there were Black slave owners in America. Jones’s masterful epic exposes the reality that slavery corrupted our entire culture, one in which Blacks could also behave with casual cruelty. In Jones’s fictional world, even African Americans are baffled and compromised by the rules of the racial hierarchy. When one of the main characters, a Black woman, takes her Black slave as a lover, she agonizes over whether this is miscegenation. The Known World of antebellum America is filled with painful contradictions.

Why do so many prominent Black novelists continue to write about slavery? “Slavery is the ground zero of the African-American experience,” says Natasha Barnes, Associate Professor of English and Black Studies at the University of Illinois at Chicago. “For too many years it has been ignored. Ignored as a historical topic, in the fictional landscape and in film. Because racism is the unacknowledged sin in American history and life, to me there are always going to be African Americans wanting to make those connections, to look back.”

Barnes, who has studied and written about lynching photography, is noticing a growing interest in history that makes these slavery narratives marketable. “There’s a new pursuit around memory, around authenticity. To some extent the Holocaust memorials have been on the foreground on this. We had the U.S. Holocaust Museum before we had any Museum of slavery. And of course that raises questions about what do we do with our own history, particularly the history that goes against the mythology of American exceptionalism.”

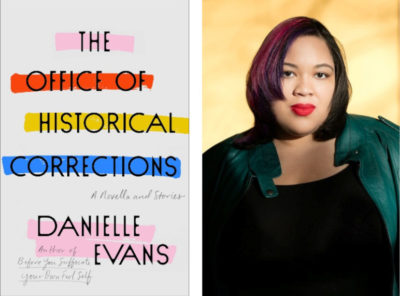

Though set in the present day, author Danielle Evans’s new novella and short story collection, The Office of Historical Corrections, creatively confronts the horrors of America’s history of racial conflict. The protagonist of the titular novella, Cassie, works for a fictional federal agency, the Institute for Public History, where she is tasked with revising historical wrongs and setting the record straight. This includes correcting everything from historically inaccurate product marketing, to textbooks, to historical plaques. “I think the questions that motivated me to write the story are in part larger questions about U.S. history and how we make room for a more complicated narrative,” says Evans.

Like Edward P. Jones, Evans also examines divisions within the Black community over what responsibility they have to bring attention to America’s racial injustices. One of Cassie’s colleagues is a Black historian who’s become more radical over time, demanding America confront its crimes and call out not just the names of victims, but the perpetrators, something Cassie is reluctant to do. At one point, her colleague says in a staff meeting that “we were tiptoeing around history to the point that we might as well be lying to people.” It’s a conundrum Evans seems to struggle with as well. “I do think a lot about the James Baldwin line, ‘It is the innocence which constitutes the crime,’ which does seem to me to be related to our problems with confronting the reality of racism and white supremacy,” says Evans. “There is only a national will to address it if it can be addressed in a way that absolves and protects whiteness.”

The main characters in Jesmyn Ward’s National Book Award-winning novel, Sing, Unburied, Sing, are haunted by history — the actual ghosts of two murdered Black boys. The 2017 novel explores another lasting legacy of slavery — a judicial system with racial disparities and the mass incarceration of Black men. One of the main characters is incarcerated as a child during the Jim Crow years in Mississippi’s notorious penitentiary, Parchman Farm. After the Civil War, Mississippi instituted a convict lease system, where prisoners were leased out as laborers. In Ward’s novel, Black men are arrested for minor crimes, such as loitering, and left to toil for years as farmhands for no pay under the rifle of a prison overseer. Ward’s imaginative and emotional retelling of history forces readers to question connections between today’s judicial system and the slavery of the past.

Will we continue seeing slave stories from Black novelists? Professor Natasha Barnes would like to see see Black novelists immerse themselves in America’s Reconstruction period, which she views as a unique, potentially heroic and tragic story that still has not yet been told. However, she expects slavery narratives will continue consuming Black novelists. “I don’t think we’re through with slavery for a long time. We are grappling with it, rewriting it. We’re here in slavery to stay for a while, because it is our Holocaust.”

Featured image: Biraj Roy / Shutterstock

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Reconstruction after the Civil War was abruptly terminated when the healing process had not yet been completed.

Today, after the Great Recession and the hardships of the Covid-19 pandemic, America is once again deeply (and tragically) divided. However, my hope is that the recent attack on the Capitol will go down to history as the peak of such divisiveness.

This new wave of enthusiasm that is surrounding Black novelists (and poets) is an encouraging sign, in this regard: Black novelists’ success is America’s success — the willingness to understand, learn, heal.

It’s time to complete the unfinished Reconstruction that started over 150 years ago – it’s time to deal with the past, face the present and prepare for the future.