When most think of Zelda Fitzgerald, perhaps the profile of an unhinged alcoholic, a dead weight to her husband F. Scott Fitzgerald’s career, or her striking death by fire that occurred 73 years ago today come to mind. However, up until quite recently, her life as an author, muse to her husband, and her truly liberated nature are often left out of her narrative. Zelda was criticized in her time, erased from her husband’s story, and as a result of several Hollywood adaptations of her life, has experienced the pen of revisionist biographers. Zelda was troubled and imperfect but also lived life authentically and for herself.

Her story begins at the turn of the 20th century in Montgomery, Alabama — an unexpected hometown for the woman who Scott labeled as “the first American flapper.” Born to Alabama Supreme Court Justice Anthony Dickinson Sayre, Zelda grew up living amongst high society. Her affinity to the luxury lifestyle led her to question Scott’s viability as a suitor when they met while she was in high school and he was stationed at Camp Sheridan during World War I. The financially precarious lifestyle of a writer did not particularly entice Zelda. Only after Fitzgerald published his debut novel This Side of Paradise did Zelda agree to marry him.

Due to the novel’s immense success, the couple soon reached celebrity status. As Fitzgerald became the shining star of the Jazz Age of literature and the couple generated more and more fame, they decided to cross the Atlantic and live in France with a group of rowdy expatriates. It was in Paris where Fitzgerald completed his third, and at the time most disappointing work, The Great Gatsby.

While in France, the Fitzgeralds surrounded themselves with an illustrious crew from the Lost Generation, including Sara and Gerald Murphy, Dorothy Parker, and Ernest Hemingway.

It was along the French Riviera where Zelda’s personality and personhood became her own. According to Nancy Milford’s 1970 book, Zelda, almost immediately upon arrival to France, Gerald Murphy noted that “Zelda had her own personal style; it was her individuality, her flair.” She brought the exuberance of 1920s New York to southern France through her taste that was, as Murphy said, “never what one would speak of as a la mode — it was better, it was her own.”

A late evening at a casino in Antibes chronicled in Zelda epitomized Zelda’s unique nature. After most of the guests had retired, the Fitzgeralds and the Murphys remained in the dancehall, drinking and talking. Out of nowhere, Zelda jumped on top of her chair and began to dance. The orchestra turned their attention to the enthusiastic young woman and began to play for her. Gerald Murphy recalled that “She was dancing for herself; she didn’t look left or right, or catch anyone’s eyes. She looked at no one, not once, not even at Scott.” He went onto say, “We were frozen. She had this tremendous natural dignity. She was so self-possessed, so absorbed in her dance.” This intense individuality and desire to act without an agenda or objective was a mainstay in Zelda’s life. On the Riviera, she danced to dance — and for no other reason.

However, Zelda’s lifestyle was not always a popular one. Her vivacious and eccentric personality clashed with Hemingway in particular. According to Zelda, she saw Hemingway as “pain in the neck” and once told Scott that “he’s as phony as a rubber check and you know it.” Hemingway pulled Scott aside when he first met Zelda to inform him that his wife was crazy.

Zelda and Hemingway were seemingly in constant competition over Scott, leading to their almost immediate hatred for one another. In his posthumous memoir, A Movable Feast, Hemingway identified two forms of jealousy in the Fitzgeralds’ marriage: Zelda being jealous of Scott’s work and Scott being jealous of Zelda.

The Hemingway narrative of Zelda became the dominant one of the times — he portrayed her as being the drunk who stifled her genius husband’s work. However, Scott struggled with addiction himself, having been hospitalized eight times between 1933 and 1937 for alcoholism. And far from stifling his work, there is evidence that Scott plagiarized directly from Zelda’s work and used her as inspirations for some of his characters.

According to Salon, for his second novel, The Beautiful and the Damned, Scott directly plagiarized pages out of Zelda’s personal diary, leading her to write a review of the book in the New York Herald Tribune saying, “In fact, Mr. Fitzgerald — I believe that is how he spells his name — seems to believe that plagiarism begins at home.”

Although Zelda is best known as a muse for Scott, she herself did use her life as inspiration to publish her own work. Following a mental health crisis that resulted in her first being institutionalized in France and then transferred to a Swiss hospital in 1930, the couple moved back stateside. In 1932, Zelda entered a psychiatric clinic in Baltimore where she began to write her first and only novel: Save Me the Waltz.

Save Me the Waltz was Zelda’s chance to tell her own story. The semi-autobiographical account follows her childhood growing up in the deep South and her turbulent marriage. Ultimately, the book was a flop and did not reach the heights she hoped it would. Given that Zelda wrote the novel when she was struggling with her schizophrenia, it is impossible to imagine the success she might have had if she had told her own story earlier in life rather than allowing Scott to write it.

Eventually the couple separated — Scott went off to Hollywood and Zelda was passed around sanitariums across the country. In 1940, just six years after releasing Tender Is the Night, Scott died by heart attack at age 44 — a consequence of his alcohol and tobacco addictions. Zelda was admitted to the Highland Hospital in Asheville, North Carolina in 1936 and stayed there until she died on this day in 1948 at age 47 in a hospital fire.

Zelda’s desire for liberation and for life itself defines her to this day. This burning vitality is what drew Scott to her. He wrote: “I fell in love with her courage, her sincerity and her flaming self-respect, and it’s these things I would believe in even if the whole world indulged in wild suspicions that she wasn’t all that she should be.”

Zelda’s story has been given the “Hollywood Treatment” with two feature films in the works and an entire series dedicated to piecing together her narrative. It has taken half a century for the public to want to observe Zelda’s life from her own perspective, rather than from the paradigms of powerful men around her.

Zelda’s outlook on life was one of existentialism, where the only thing that mattered is life itself. As Zelda put it “‘All I want is to be very young always and very irresponsible, and to feel that my life is my own to live and be happy and die in my own way to please myself.”

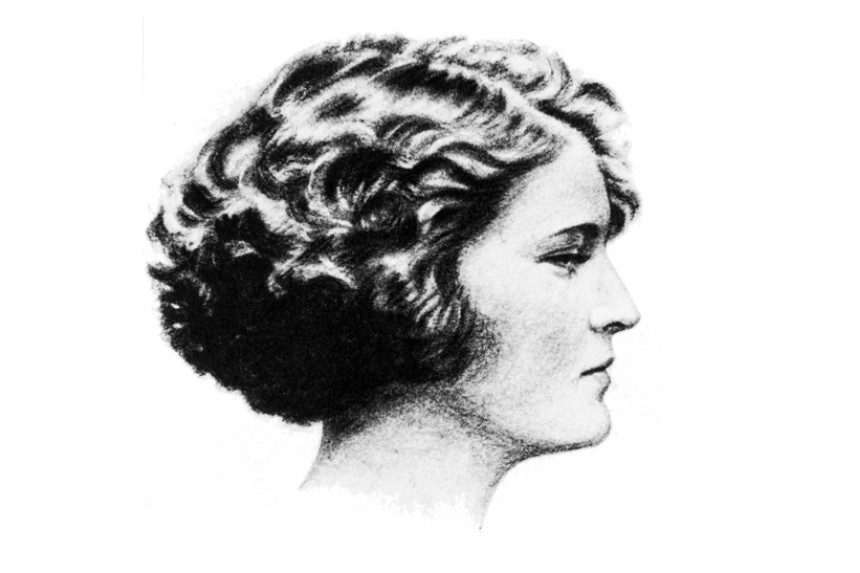

Featured image: Zelda Fitzgerald from Metropolitan Magazine, 1922 (Wikimedia Commons)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

In the article I saw no reference to perhaps what was/would have been Fitzgerald’s greatest literary work which was 3/4 way of being finished at the time of his passing, “The Last Tycoon.” It long has been speculated that the central female character of this amazing novel was modelled after Zelda herself from memories of better times in their marriage. It’s unfortunate he was unable to finish this amazing novel himself. I know there were a group of writers who studied his notes left behind and completed it they best they could arrive and agree it should have been, but in my opinion he would have really shined with this novel had he lived to complete it himself.

Zelda Fitzgerald remains a fascinating figure (of the first half) of the 20th to this day. I never knew of the feud she had with Ernest Hemingway. I can only imagine what was said in their arguments, and who told who off more. I suppose the forthcoming films will attempt to fill in those blanks with their dialog.

Scott, Zelda and Ernest all had tragic deaths. In the case of the latter two she absolutely would have been greatly helped by modern drugs and therapy for her schizophrenia where she likely wouldn’t have had to wind up in sanitariums hospitals. She wouldn’t have died only in middle age either. Hemingway, had he been on modern drugs for depression (with therapy) may not have had the intense feeling of no longer wanting to be alive, thereby not committing suicide in 1961. Unfortunately this problem is only getting worse.

It’ll be interesting to see how these two movies will compare to one another, and if they put in 21st century phrases like “You’ve got this” or using “issues” instead of the real word, problems. Not good if they do. One thing’s for sure, new films centered around the ’20s are one the only ways THIS decade can have any kind of positive identification being the ’20s other than Covid.