—From “Have You Ever Been a Boo-Hoo?,” March 21, 1964

Doctor Hubbard is a big, orange-haired, 52-year-old American who describes himself as an author, explorer, scientist, boatsman, engineer, glider pilot, philosopher, movie writer, and student of the occult. The most fascinating side of his many-faceted character, however, is the “Doctor” before his name. He is not an M.D. but a D. Scn., which stands for “Doctor of Scientology.”

This is a degree that brings a look of puzzlement to a Johns Hopkins or a Harvard registrar, but Scientology, a growing international movement with branches on all five continents, is close to Dr. Hubbard’s heart. He is not only its head and best-known practitioner; he actually invented it. Essentially Scientology is an outgrowth of an American fad of the early 1950s called Dianetics, also invented by Dr. L. Ron Hubbard. Scientology purports to be a “religion,” but it is not affiliated with any of the broad U.S. church movements. It has elements that resemble psychoanalysis, though leading psychiatrists bitterly reject it. Even Hubbard himself seems to have difficulty defining it. He currently calls it “the common people’s science of life and betterment,” but this is only the latest of a series of definitions that he has tried and discarded. In view of its tremendous scope, its odd procedures, and the remarkable feats claimed for it, an attempt to compress Scientology into the few words of a definition is much like trying to gift-wrap a dozen live eels.

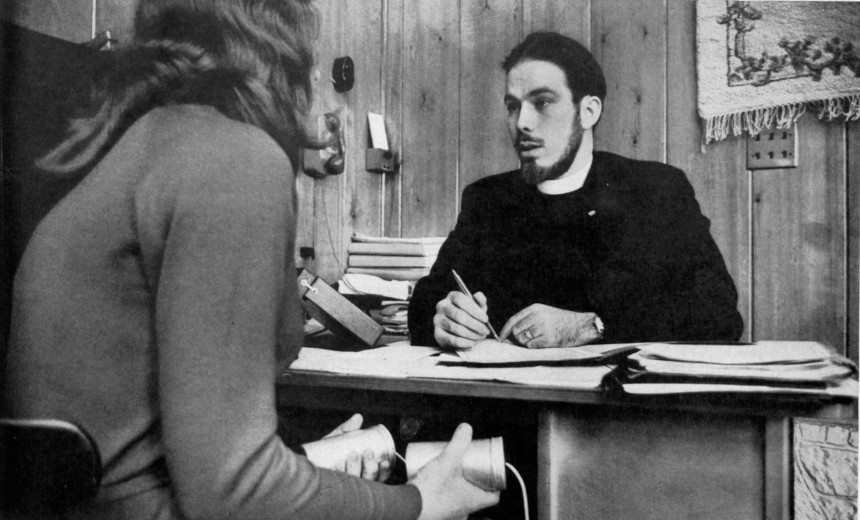

It is easier to explain what Scientologists do. For a fee, Hubbard’s followers will “audit” or listen to people who have troubles. They use a small, battery-run machine known as a Hubbard E-meter while they are auditing the people with troubles, whom they call “preclears.” The machine has two wires running out of it, and these are clamped to a couple of tin cans, which the “preclear” holds while he is being audited. The E-meter has knobs and a large dial with a needle, and as the person talks, the needle moves around, which presumably means something to the Scientologist.

As Hubbard explains it, “The meter tells you what the preclear’s mind is doing when the preclear is made to think of something. If they’re emotionally disturbed about cats, and they’re talking about cats, the needle flies about. If they’re not disturbed about cats, the needle doesn’t fly about. So you let them talk about cats until they’re no longer disturbed about cats, and then the needle no longer flies about.”

The goal, of course, is to get to “clear.”

At various times Hubbard has held that Scientology “can cure some 70 percent of man’s illnesses,” that it is the counterforce to the H-bomb threat, and that it can make you immune to the common cold. He maintains that Scientology can raise a person’s I.Q. one point per hour of auditing. (“Our most spectacular feat was raising a boy from 83 I.Q. to 212,” Hubbard told this reporter.) He claims that it can improve the performance of astronauts and help jet pilots avoid crashes, that it can “arrest the aging process” and make you look younger, that it will restore psychotic persons to sanity much faster and cheaper than psychiatry. (“I saw Ron do it in an asylum,” says a California follower. “He just went along snapping his fingers at them and saying, ‘Come up to present time! Come up to present time!’”)

And along with all this, says Hubbard, a Scientologist can move a person out of his body and let him stand over in a corner and look at himself. “We don’t like to publicize this,” says Hubbard, who has publicized it in his pamphlets. “It makes people uneasy.”

If these marvels seem reminiscent of the old-time snake-oil peddler, let it be said that there is nothing old-time about L. Ron Hubbard. A few feet from his desk stands a Telex, giving him instant communication with his far-flung branches. Hubbard speaks easily and with seeming authority about physics, mathematics, nuclear fission, or indeed, almost any science, and salts his conversation with phrases like “small energy measurement,” “stimulus-response cycle,” and things like that. Scientology literature frequently refers to him as an engineer, a mathematician, and a nuclear physicist. Who’s Who in the Southwest credits him with an engineering degree at George Washington University. The university does not. Today, besides his “Doctor of Scientology,” he appends a Ph.D. to his name. He got it, he says, from Sequoia University. This was a Los Angeles establishment, once housed in a residential dwelling, whose degrees are not recognized by any accredited college or university.

Hubbard, who was born in Tilden, Nebraska, in 1911, has been married three times, divorced twice, and is the father of seven children. Somewhere along the way he took up the writing of science fiction, and both Dianetics and Scientology show the strong influence of his former craft. Both Scientology and science fiction are characterized by arcane words and by invented terms, phrases, and abbreviations. Hubbard’s followers also deal with and knowingly discuss such things as down-bouncers, Thetans, MEST bodies, lock-scanning, dub-ins, rock slams, bops, and engrams.

Fees vary in the academies, but you can get a short, “intensive” course of hours for $700 or $800. According to a Scientology pamphlet, “A complete Freudian analysis costs $8,000 to $15,000. Better results can be achieved in Scientology for $25 and, on a group basis, for a few dollars.”

Unfortunately Scientology does not straighten out every client at these bargain-basement figures. Police cited a record of a Florida millionaire who spent $28,000 on Scientology processing in less than two years. His only complaint was of “nervousness.”

People who encounter Scientology for the first time are astounded at its far-flung growth. Actually Scientology did not have to start from scratch but was able to rise phoenix-like from the ashes of Dianetics, a craze which swept the U.S. in 1950. It originated with a book that Hubbard wrote in 60 days called Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health. Overnight, Dianetics became a runaway best seller, although the learned journals of psychology, psychiatry, and medicine all ignored it.

Dianetics preached that everybody had two minds, the “analytical,” similar to Freud’s “conscious,” and the “reactive,” like Freud’s “unconscious.” The analytical mind, Hubbard maintained, was a perfect computing machine, incapable of error — except for “engrams,” which fouled up the computer. Engrams were recorded on your “time track” by your reactive mind, when your analytical mind wasn’t looking. For example, said Hubbard, “A woman is knocked down by a blow. She is rendered unconscious. She is kicked and told that she is no good. A chair is overturned in the process. A faucet is running in the kitchen. The engram contains a running record of all these perceptions.” Later, the engram gets “keyed in” and all sorts of things can happen; the woman may feel a sensation of being kicked whenever she hears a faucet running.

Dianetics taught one how to erase engrams by auditing. You “returned” a person on his time track to the time of the engram and had him talk it out by “reliving” it. Once all the engrams were erased, a person would become a “clear” — highly intelligent, healthy, with a great zest for life, enormously improved abilities, and a perfect memory. In short, a giant among pygmies. Dianetics was enough like psychoanalysis to impress a good many people, and also had the advantage that anyone who bought Hubbard’s book could play doctor at home, without all those tedious years in medical school. In no time hundreds of thousands of Americans, armed with Hubbard’s book, were playing Sigmund Freud for each other.

Hubbard established one important difference between Scientology and Dianetics. Instead of presenting it to the public as a science equal in importance to the discovery of fire, he set it up as a religion. At the outset this move distressed his followers, some of whom were science-fiction fans, free-thinkers, and even agnostics. But the rebellion dwindled, and the new faith went forth. With scarcely a whisper of publicity, Scientology spread and prospered.

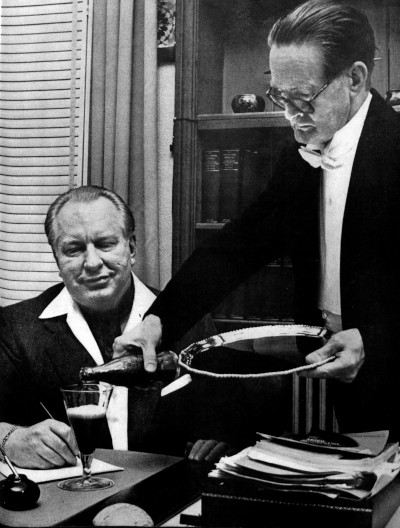

Hubbard himself took it to England, found that he liked the country, and settled there in Saint Hill Manor, a spectacular mansion in Sussex, about 30 miles south of London, that was formerly owned by the Maharaja of Jaipur. Although he is founder and unquestioned titular head of the Church of Scientology, Ron Hubbard does not look upon himself as patriarch, pope, bishop, or even elder. “I control the operation,” he says, “as a general manager would control any operation of a company.”

According to Hubbard, a Scientologist can move a person out of his body and let him stand over in a corner and look at himself.

The individual churches pay 10 percent of their take to the Saint Hill center. But Hubbard insists that he does not profit from Scientology but draws only a token salary of $70 a week. He claims he is “independently wealthy” and that Scientology is a “labor of love.” Just exactly where the 10 percent goes is not clear; Hubbard says he has spent “a million dollars or two” on research. He does not like to talk about money; he responds to questions about it with a smile, a sad shake of the head, and a comment about “the American preoccupation.”

Some of his enemies have claimed that the very man who had discovered the “clear,” had never himself been processed to that high plateau of almost super-human ability. “That is the wildest pitch I’ve ever heard,” he said with indignation. “Of course I’ve been processed to ‘clear.’”

However, the definition of “clear” has been changed somewhat from the old days of Dianetics, when it meant a man freed of engrams, with a flawlessly functioning mind, fantastic abilities, and total recall. Since then Hubbard has developed a new, and slightly more modest, definition of “clear.” It now means “a person who has this lifetime straightened out.”

Having explained this, the master of Saint Hill Manor rings for his butler, Shepheardson, who fetches his afternoon Coke on a tray. If he wishes a bit of air, his chauffeur will wheel out a new American car or his Jaguar. And as he sits there, gazing contentedly out over the broad acres of what was once a maharaja estate, the profound truth of what he says becomes apparent. Lafayette Ron Hubbard, Doctor of Scientology, may indeed be a man who has this lifetime straightened out.

This article is featured in the September/October 2021 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: calimedia / Shutterstock.com

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

All I can say is, ROTF LMAO!

Interesting that Trump used to have a diet Coke served to him on a silver tray in the Oval Office.

Hubbard was no fool and only declared

Scientology a religion for the tax free status.

The pseudo-science behind it can be very useful

to some,as proven by its continuance.

Wasn’t it Hubbard who once said, “The way to make a fortune is to invent a religion”? I believe he is an inventor.

L Ron Hubbard was a nut, somewhere along the lines of a poor donald j trump. Society shouldn’t be seriously listening to anything either one has to say.