When the Beatles stepped from the plane, 1,500 people shrieked a welcome from the roof of Liverpool Airport. This was only the vanguard of the 150,000 who lined the 10-mile route to the town hall. On the drive to the city, the Beatles had an eight-motorcycle escort. The mobs kept breaking through the police lines to claw at their car, while the police motorcycles raced down both gutters, making spectators jump hot-footedly back onto the curbs. Along the way the motorcycle police heard radio reports that there was rioting at town hall.

The Beatles were home. They were back in Liverpool for the opening of their first movie, A Hard Day’s Night.

At the Liverpool town hall the first of the 400 persons hurt that day were being carried on stretchers from the crowds surging and screaming behind the barricades. The Beatles were rushed into the office of the Lord Mayor, a small mustached man named Louis Caplan. He was wearing white tie and tails and something called the Lord Mayor’s evening jewel, a cameo which hung from his neck by a blue ribbon and was decorated by the Liverpool coat of arms surrounded by diamonds, emeralds, and rubies. The first thing that John did was to press his nose against the jewel.

In the town-hall plaza some 20,000 people were screaming for the Beatles. The Lord Mayor, up for reelection next year, announced he was taking the Beatles to the town-hall ballroom. As he led them up the grand staircase, a police band, concealed below, broke into a Beatles hit, “Can’t Buy Me Love.” Ringo danced all the way upstairs. In the ballroom, a noisy crowd of 700 invited guests joined with 400 uninvited guests in storming a long, linen-covered table laden with canapés, cakes, and whiskey. When the Beatles entered the ballroom accompanied by a single constable, the mob changed direction and attacked them. The Beatles were crushed against the table by the stampede of well-wishers. While they stood there gasping, officials on the other side of the table showed them a giant cake decorated with a map of the world and the routes they had taken over it outlined in red.

From the town hall the Beatles drove through another cheering mob of 20,000 to the Odeon Theater for the local premiere of their film. On the stage of the theater a telegram of congratulations from Prince Philip was read. Offstage, Lord Derby placed a request from Queen Elizabeth for six autographed souvenir programs.

Then the Beatles rode back to the airport. It was dark and it was raining, but scattered clumps of people on street corners shouted greetings.

“In another year I’ll have me money and I’ll be out of it,” said John.

It was a frantic day, but wholly typical. Since their visit to America last February, the Beatles have lived at jet speed. They visited the South Seas and the West Indies where, the British press reported with gleeful cattiness, Beatles Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr were accompanied by Paul’s 18-year-old girlfriend, actress Jane Asher, and Ringo’s 17-year-old secretary-to-be, hairdresser Maureen Cox. The Beatles also completed A Hard Day’s Night, a low-budget movie which Brian Epstein, the Beatles’ 29-year-old manager, blithely predicted would earn the largest profit in film history. They toured New Zealand and Australia, where as many as 300,000 people not only howled greetings but sometimes trampled one another underfoot. In Australia the Beatles left behind an estimated 1,000 casualties. One girl burst a blood vessel in her throat from screaming. About a dozen fans were kicked by police horses. Another girl suffered carbon monoxide poisoning when she was knocked down near the exhaust pipe of an automobile hemmed in by the mob. When she tried to get up, she was pinned there by several other girls, who had climbed on her back to get a view of the Beatles.

Amazingly, it has been little more than a year since the last zippered leather boot of the Beatles climbed the winding dungeon steps out of Liverpool’s Cavern Club, leaving behind the distinctive local delirium which they created and which created them.

A city of 750,000 persons, Liverpool has played a disproportionately large role in the musical life of Britain since the emergence of the Beatles. It is a gray city, its stone houses mirroring the almost constantly overcast skies. Its people are small, tough, and wiry, attenuated by the spare diets and frequent malnutrition that result from the meager factory wages in northern England. It has one of the highest unemployment rates in England, a fact that helps account for the feeling among Liverpudlians that they aren’t a part of England at all. There was a time when Liverpool, a seaport on the slimy mouth of the Mersey River, even issued its own money. There are still iron rings on the docks where slaves were chained before shipment to the colonies, in open defiance of the crown. The big colonnaded stone mansions on Upper Parliament Street and Gambia Terrace have been broken down into the tiny flats of Liverpool’s Harlem, and Lennon himself used to live in one of them. His friends still talk about the winter he chopped up the furniture to heat the flat, and about the time a London newspaper sent a photographer to take pictures of it for an article on England’s beat generation. Lennon threw the photographer out.

Since the advent of the Beatles, rock ’n’ roll music has begun to overturn the caste system in other English cities. Hardly a day goes by without a front-page story about some group’s exploits. The BBC has been forced to increase its pop-music programming, and youngsters wait eagerly each week for the latest pop-record charts. Whoever has the No. 1 record also has at least seven days of acclaim as a national hero.

It could only have started in Liverpool, where the football fans are barred from British railways because of a Liverpudlian tendency to rip seats apart in celebration of either victory or defeat. Things are no different at the Cavern Club. On one recent night a group of youths somehow managed to find room in the crush to start a fight. Immediately another platoon of youths rushed to a cache of empty pop bottles and grabbed them, one by one, like soldiers taking rifles off a waiting stack. An instant later there was the murderous splash of breaking glass on the walls of the room. But the fight didn’t last long. The Cavern Club bouncers leaped into the center of the brawl within seconds and emerged dragging two boys by their arms across the floor and then up the stairs, bouncing them along on the stone steps as if they were rubber balls. Through it all, the group onstage never missed a beat. On the floor the club’s inhabitants twitched through wild, nameless dances, their bodies controlled like puppets by the guitar strings. The steam of cigarettes and heat covered everything. It crept up the stairway and billowed through the narrow, unadvertised Cavern Club door into Mathew Street, turning into white clouds in the cool air outside. More than once fire engines had to rush to Mathew Street when passersby, noticing the smoke, thought the Cavern was burning.

Taxicab drivers refuse to enter Mathew Street, a canyoned gauntlet of broken glass, miniature vans parked helter-skelter, and gangs of 15-year-olds with collarless jackets, no ties, and no restraint on their Liverpool language, known as Scouse. On one night this summer in Mathew Street one of the gangs was hurling words and kicks against a tiny car, while the occupants, a group of musicians who had just finished playing the Cavern, shouted back through closed windows. When the car finally drove off, the gang surrounded a tourist and asked for cigarettes, while one gang member elegantly cleaned his nails with an open penknife. “The Beatles,” one of them said in the upward tilt of the Scouse dialect that makes every sentence sound like an unasked question. “Ahhh, the Beatles are finished in Liverpool. It’s the Rolling Stones you want to hear.”

“Except,” says 34-year-old Alan Williams, the short but ready-fisted owner of Liverpool’s nightclub the Blue Angel, “the Beatles don’t belong to Liverpool anymore, they belong to the world. You know, I used to be manager of the Beatles. It was all done on a handshake. One bloody nasty paper said I now cry myself to sleep. That’s ridiculous. I couldn’t have done what their present manager, Brian Epstein, did for them.”

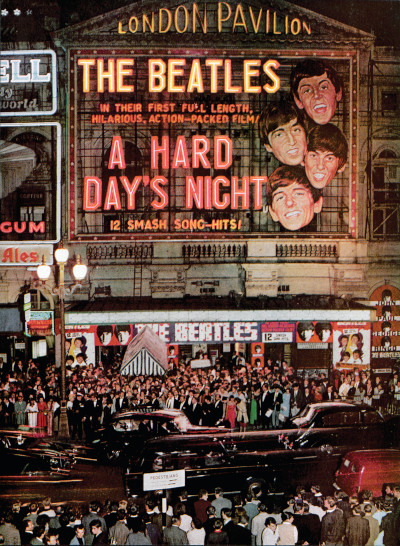

What Epstein has done for them was demonstrated graphically at the London premiere of the Beatles’ new movie which took place only a couple of nights before the hoopla in their hometown. There were 12,000 people in Piccadilly Circus. Two hundred policemen held the crowd back as several fights broke out. When the Beatles arrived, there was an immense throaty roar. Afterward the theater manager rolled out a newly cleaned red carpet for Princess Margaret. She walked in, tiny and smiling, with her husband, Lord Snowden, trailing behind. The theater was worn and smoky. A detachment of trumpeters blew a tinny fanfare from the stage, and the metropolitan police band played “God Save the Queen.” Then the theater darkened, and a short preliminary film colored the screen. It was a travelogue of New Zealand, and the Beatles snickered knowingly. “New Zealand,” John said afterward, “is a drag.” After the movie played, the princess asked Paul what he thought of it. “I don’t think we are very good, Ma’am,” Paul answered, “but we had a very good producer.”

There was a party afterward in the Dorchester Hotel, and the princess came. So did Brian Jones and Keith Richards, two members of the popular new quintet called the Rolling Stones. The party was formal, with gowns and black ties, but Jones and Richards were wearing turtleneck shirts. “Isn’t this the greatest party crash of all time?” said Jones. The Rolling Stones’ latest record, It’s All Over Now, had just hit the top of the British pop charts, and the Beatles came over to congratulate them. An elderly woman came up to John and said, “You’re simply darling.”

“Can’t say the same for you, Luv,” John replied. Later, as the party broke up, he told her, “Good night, Mrs. Haitch. We’ll dance again some Somerset Maugham.” Meanwhile a crowd of begowned autograph hunters were besieging the Rolling Stones. Brian Jones was still signing his name when the orchestra began playing “God Save the Queen.” “Stop it,” a diamond-necklaced woman at his table commanded sternly. He kept on signing. “Stop it!” she commanded again, this time with the fury of the empire in her voice. Jones stopped signing and picked up a woman’s scarf, which was lying on the table in front of him. Slowly, to the solemn tones of the music, he wrapped it around his neck. When the orchestra came to the final verse, an off-key voice at the front of the ballroom shrieked out the word “save.” It was John Lennon, and what he had sung was, “God sa-a-a-ve the cream.”

“They’re rude, they’re profane, they’re vulgar, and they’ve taken over the world.”

After the party, John, Paul, and Ringo went to the Ad Lib, an after-hours club. Paul left early. Ringo was the next to go. John continued drinking Scotch and Coke. His hand gripped his glass as if he were trying to crush it. His eyes seemed hard, sharp, and unsmiling. His upper lip sometimes curled as he talked, displaying his teeth. “I love you,” he told Brian Jones and Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones. “I loved you the first time I heard you. But there’s something wrong with you, isn’t there? There’s one of you in the group that isn’t as good as the others. Find out who he is and get rid of ’im.”

For a while they argued about music. The Rolling Stones play American Black rhythm-and-blues. The Beatles, they said, were playing white commercial rock ’n’ roll. They argued about hairstyles. “Your hair makes it,” John told Brian Jones. “Your hair makes it,” he said to Keith Richards. “But Mick Jagger,” he said, “you know as well as I do that his hair doesn’t make it.”

“It’s harder for us than it was for you,” said Brian Jones, “because we have to contend with you and America. You only had to contend with America.”

“Ahhh,” said John, “in another year I’ll have me money and I’ll be out of it.”

“In another year,” said Brian Jones, “we’ll be there.”

John took a drag on his cigarette. “Yeah,” he said, “but what’s there?”

What is there? The question bothers Paul, too. “Have there been any changes in us?” says Paul. “The main thing is the cash. Isn’t it? The cash is the big change. And the cash changes you. But it can’t change you really inside, because to go big-headed, you got to be big-headed anyway — I think. The danger is in narrow-minded people, soft people, who will say, ‘Ah, it’s gone to their heads.’ But I think we’ve always had some kind of faith in ourselves — which you need to do anything in show business.”

The Beatles wonder about themselves and draw no answers. “Here are these four boys from Liverpool. They’re rude, they’re profane, they’re vulgar, and they’ve taken over the world,” says Derek Taylor, the Beatles’ press officer. “It’s as if they’d founded a new religion. They’re completely anti-Christ. I mean, I’m anti-Christ as well, but they’re so anti-Christ they shock me, which isn’t an easy thing. But I’m obsessed with them. Isn’t everybody? I’m obsessed with their honesty. And the people who like them most are the people who should be outraged most. In Australia, for example, each time we’d arrive at an airport, it was as if de Gaulle had landed, or better yet, the Messiah. The routes were lined solid, cripples threw away their sticks, sick people rushed up to the car as if a touch from one of the boys would make them well again. It was as if some savior had arrived.”

Taylor paused. “The only thing left for the Beatles,” he said, “is to go on a healing tour.”

—From “The Return of the Beatles,” August 8, 1964

This article is featured in the September/October 2021 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: John Launois,© SEPS

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Fascinating that this article would have appeared in August, 1964, and caused, as I remember, not the slightest stir, at all. I’m stunned that Derek Taylor’s remarks were ignored by the public.

As always, Lennon, a head case if there ever was one, was hilarious ( and rather mean ).

Lennon thought, and I agree with him, that Michael Braun’s book, “Love Me Do,” was the best thing – the most honest thing – written about the band. Braun, an American, was in England in mid – 1963. His instincts told him The Beatles were going to be something extraordinary, and he was allowed to be “embedded” with them for most of the next year. If you’re a Beatles fan, you’d enjoy it.

A fascinating insider’s look at the legendary band, even more so 57 years later. Alfred’s report takes you on a ride with the Beatles you wouldn’t have gotten to go on otherwise. As young a they were in ’64, I can see how and why they would have been overwhelmed, and needed the out of control spin cycle they started to stop, or at least slow down. Easier said than done.

This also explains the need they would have for inner peace and desperately sought it out. The Post covered that very well several years later in a very different section of the 60’s for the Beatles, and everyone else. By the way, the beginning of what would become the Beatles began 64 years ago when John and Paul first met in the summer of ’57. It was so crucial yet is almost entirely overlooked. Important things ironically often are. This is why (fortunately) the beginning and end dates of the Beatles are listed as 1957-1970.

The timing of a new look at this feature is well timed, as ’64 and ’57 ARE 57 and 64 years ago in 2021.