—From “How to Avoid Sudden Death,” July 16, 1955

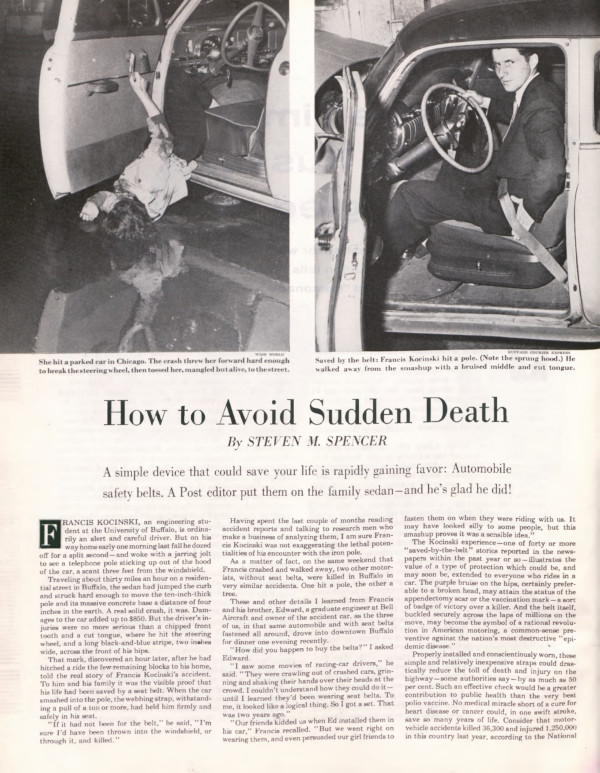

Traveling about 30 miles per hour on a residential street in Buffalo, the sedan had jumped the curb and struck hard enough to move the 10-inch-thick pole and its massive concrete base a distance of four inches in the earth. A real solid crash, it was. Damages to the car added up to $850. But the driver’s injuries were no more serious than a chipped front tooth and cut tongue, where he hit the steering wheel, and a long black and blue strip, two inches wide, across the front of his hips.

That mark, discovered an hour later, after he had hitched a ride to his home, told the real story of Francis Kocinski’s accident. To him and his family it was the visible proof that his life had been saved by a seat belt. When the car smashed into the pole, the webbing strap, withstanding a pull of a ton or more, had held him firmly and safely in his seat. “If it had not been for the belt,” he said, “I’m sure I’d have been thrown into the windshield, or through it, and killed.”

The Kocinski experience — one of 40 or more “saved-by-the-belt” stories reported in the newspapers within the past year or so — illustrates the value of a type of protection which could be, and may soon be, extended to everyone who rides in a car. The purple bruise on the hips, certainly preferable to a broken head, may attain the status of the appendectomy scar or the vaccination mark — a sort of badge of victory over a killer. And the belt itself, buckled securely across the laps of millions on the move, may become the symbol of a rational revolution in American motoring, a commonsense preventive against the nation’s most destructive “epidemic disease.”

Properly installed and conscientiously worn, these simple and relatively inexpensive straps could drastically reduce the toll of death and injury on the highway by as much as 50 percent. No medical miracle short of a cure for heart disease or cancer could, in one swift stroke, save so many years of life. Consider that vehicle accidents killed 36,300 and injured 1,250,000 last year, according to the National Safety Council.

If strapping ourselves down will increase our chances of survival in our motorized environment, what are we waiting for?

If strapping ourselves down will increase our chances of survival in our motorized environment, what are we waiting for?

To gain acceptance, the seat belts must overcome widespread lack of information and some misinformation, and compete for the attention of car owners who are usually more interested in horsepower and body styles than in safety devices.

It will be hardly surprising, therefore, if this new revolution is a reluctant one. Unembellished common sense has never been a popular automobile accessory, and safety in all its forms has always been more energetically preached than practiced.

This article is featured in the September/October 2021 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Simply safer: Seat belts “could drastically reduce the toll of death and injury on the highway,” wrote the author in 1955. (Sid Avery, © SEPS)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Really interesting vintage yet still timely, Post feature from mid-July 1955. Ironically, only 2 and a half months before James Dean’s horrific car crash. That was just before Ford’s new ’56 models came out introducing their ‘Lifeguard Design’ safety features such as cushioned steering wheels, stronger door latches, padded instrument panels (for upon impact) and nylon seat belts.

It apparently wasn’t appreciated as it should have been by the automotive buying public at the time. It wasn’t due to lack of trying by the Post or Ford. So much had happened, but nothing had changed really, until 1968.