This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

For the last couple weeks, many conversations have focused on one unfolding event: the Madison, Wisconsin trial of Kyle Rittenhouse for the killings of Anthony Huber and Joseph Rosenbaum and the wounding of Gaige Grosskreutz. That collective focus is understandable: the trial features a teenager charged with felony homicide (among other charges), echoes and legacies of last summer’s divisive #BlackLivesMatter protests, interconnections with countless overarching American issues from guns to “stand your ground” laws to police reform to white supremacy, and a judge who is, to put it kindly, unconventional (and perhaps far more unjudicious than that).

While every murder trial, like every act of violence, is distinct and deserves attention and analysis, the collective focus on Rittenhouse has obscured a second ongoing, and even more tellingly American, murder trial: that of Gregory McMichael, his son Travis McMichael, and William “Roddie” Bryan Jr. for the February 2020 alleged killing of Ahmaud Arbery, an African American man who was simply jogging through their Brunswick, Georgia neighborhood. More than one hundred years later, we can still learn much from Ida B. Wells, the turn of the 20th century anti-lynching journalist and activist whose work and life offer us three vital lessons for understanding this 21st century trial and moment.

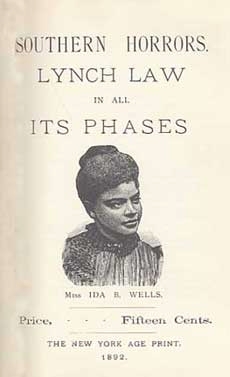

The first lesson, that of the tortured rationalizations white supremacists will offer and the mass media will too often accept for lynchings and racial terrorism, is at the heart of Wells’s first book, Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases (1892). Moving through a wide range of lynchings from that period (one that historians have subsequently deemed the worst in the century-long lynching epidemic), Wells’s book, like much of her investigative journalism overall, focuses on one consistent goal: contrasting the specific realities of each case with the narratives created by white supremacists and promulgated by the media in order to justify the racial violence.

Those white supremacist and media narratives most often focused on depicting Black men as representing a threat to white society, sexually and in every other way. As Wells puts it at the conclusion of one of her many convincing presentations of extensive evidence to the contrary: “To palliate this record…and excuse some of the most heinous crimes that ever stained the history of a country, the South is shielding itself behind the plausible screen of defending the honor of its women.” Both Wells’s investigations and analyses are worth reading as we consider the defense’s arguments that Ahmaud Arbery’s killers believed him to be a dangerous criminal and were trying to conduct a “lawful citizen’s arrest” of him.

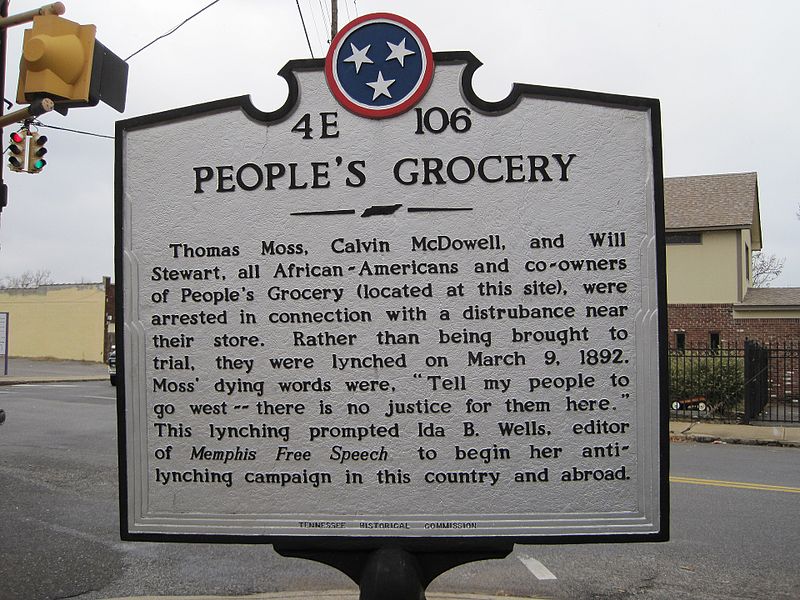

The second lesson from Wells’s work is the enraged and violent white supremacist backlash that resulted when she highlighted these realities. When Thomas Moss, Calvin McDowell, and Will Stewart, three members of her Memphis African American community, were lynched in March 1892 while defending Moss’s grocery store from a white mob, Wells wrote about that horrific event and these larger lynching contexts in the newspaper she edited, the Memphis Free Speech. Her editorials produced another and even more purposeful angry mob, this one targeting the newspaper and Wells herself. As she writes in the opening of Southern Horrors, “threats of lynching were freely indulged…letters and telegrams sent me in New York where I was spending my vacation advised me that bodily harm awaited my return. Creditors took possession of the office and sold the outfit, and the Free Speech was as if it had never been.”

Wells’s experiences with this violent white supremacist backlash can help us understand how seemingly discrete stories like the Arbery killing and the numerous state laws seeking to ban the teaching of racism and anti-racism are in fact profoundly interconnected. Educators, like investigative journalists and activist writers, help both raise awareness of and lead collective conversations about our most difficult issues and stories. No less a figure than Frederick Douglass testified to the importance of such work in an October 1892 letter which Wells includes at the start of Southern Horrors; he writes, “You have dealt with the facts with cool, painstaking fidelity and left those naked and uncontradicted facts to speak for themselves.” Because the forces of propaganda and white supremacy indeed cannot contradict these histories and realities, they seek to suppress them in every way, including with violence if necessary as Wells’s experiences reflect all too clearly.

The third and most inspiring lesson comes from Wells’s response to that violent backlash. Her newspaper gone, her life threatened, powerful forces arrayed against her, it would have been more than understandable if she paused her efforts in this fraught and painful moment. But Wells took precisely the opposite action: upon hearing of these threats she immediately pursued publication for Southern Horrors, the book that would build upon that Memphis journalism and bring it to a far more national audience and attention. As she puts it in the book’s first chapter, “Since my business has been destroyed and I am an exile from home because of that editorial, the issue has been forced, and as the writer of it I feel that the race and the public generally should have a statement of the facts as they exist.” Her work, she adds, “is a contribution to truth, an array of facts, the perusal of which it is hoped will stimulate this great American Republic to demand that justice be done though the heavens fall.”

Like so many other African American critical patriots, from Douglass to Du Bois, Baldwin to Hannah-Jones, King to Kaepernick, Wells took the occasion of these horrific histories, these threats to American communities and ideals alike, as an opportunity to argue for and model an inspiring alternative. As we face our own horrors and threats, from the death of Ahmaud Arbery to attempts to silence educators and facts, may her lessons guide our continued work.

Featured image: Marcus Arbery, Sr., father of Ahmaud Arbery, carries a portrait of his son in the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. Day Parade on January 18, 2021, in Brunswick, Georgia (Michael Scott Milner / Shutterstock)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now