Ninety years ago, Hattie Ophelia Wyatt Caraway made history as the first woman elected to the U.S. Senate. But that was just the beginning of the story. What happened after that surprised everyone, upended the Arkansas senate race, and changed the notion of what it meant to campaign.

Hattie’s husband, Thaddeus Caraway, had been a U.S. representative and then senator from Arkansas for ten years. When he passed away in November of 1931, Governor Harvey Parnell appointed Hattie to fill his seat until the next election. She easily won the special election that soon followed, which extended her post by a few months. At the time, wives were routinely appointed to fill their dead husbands’ seats, so it wasn’t at all uncommon. And while her rubber-stamped election made her the first woman senator, that in itself wasn’t remarkable. What was remarkable is what happened next.

When it came time for the Democratic primary a few months later, Hattie Caraway was expected to step aside and make way for the men. She didn’t. In a surprise move, she announced she was running for a full term. She wasn’t much of a public speaker, had little to no political experience, and enjoyed no political backing. There were six other male candidates in the primary, all with impressive credentials. Her chances looked poor.

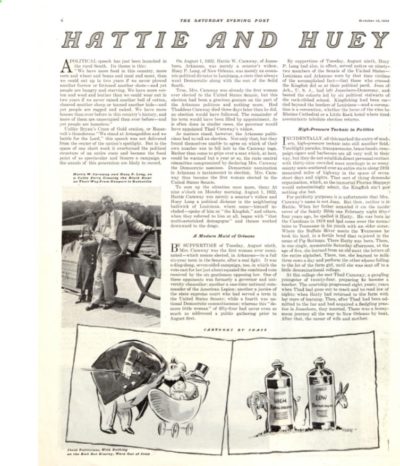

But then Huey Long, Louisiana’s powerful and populist senator, stepped in, volunteering to stump for Caraway the week before the election. Long’s involvement would change everything.

Why should a senator from a neighboring state help such an unlikely candidate? Caraway had supported Long’s most progressive (and most scorned) resolutions, so he saw a strong potential ally. On the pettier side of things, he had an axe to grind with Arkansas’s senior senator, Joe Robinson, whom he thought was in the pocket of corporate interests. He also had a soft spot for underdogs. Long told her that he would help her, and that they could get it done in just one week. In his October 15, 1932, article for the Post, journalist Hermann Deutsch quoted Long as saying, “That’s all we need. That won’t give ’em a chance to get over their surprise.”

Long set his machine in motion, and they relentlessly covered every inch of the state. Their town-by-town campaign was a tour de force involving advance men, a motorcade of seven trucks, platforms, loudspeakers, flyers, stickers, posters, and a cadre of crowd-minders whose main job was to quiet crying babies (the trick was giving them ice water). Many voters came out just to see Huey Long’s antics and outrageous comments. Deutsch noted, “He is a political revivalist; a Democratic gospel shouter, who transmutes ponderous abstractions into the idiom of the people with a glib plausibility that is uncanny.”

The crowds grew larger with each passing day. By the time they got to Little Rock, there were 25,000 people gathered to hear Caraway and Long speak. The feverish campaigning, if not unprecedented, was unusual, and her opponents never knew what hit them. They were “bewildered by this high-pressure disturbance which moved across the land with such clocklike regularity, military precision and devastating effect. By the time they had rallied their political faculties and begun to strike back, the damage had been done.”

The fight for that senate seat was a “ding-dong, seven-sided campaign, too,” but Hattie Caraway came out on top, garnering twice as many votes as the second place finisher. Much can be attributed to Long’s influence, but the unassuming Caraway left some powerful speeches in her wake. On the campaign trail, she captured the crowd by railing against America’s inequities, felt keenly in the midst of the Great Depression:

We have more food in this country, more corn and wheat and beans and meal and meat, than we could eat up in two years if we never plowed another furrow or fattened another shote—and yet people are hungry and starving. We have more cotton and wool and leather than we could wear out in two years if we never raised another boll of cotton, sheared another sheep or tanned another hide—and yet people are ragged and naked. We have more houses than ever before in this country’s history, and more of them are unoccupied than ever before—and yet people are homeless.

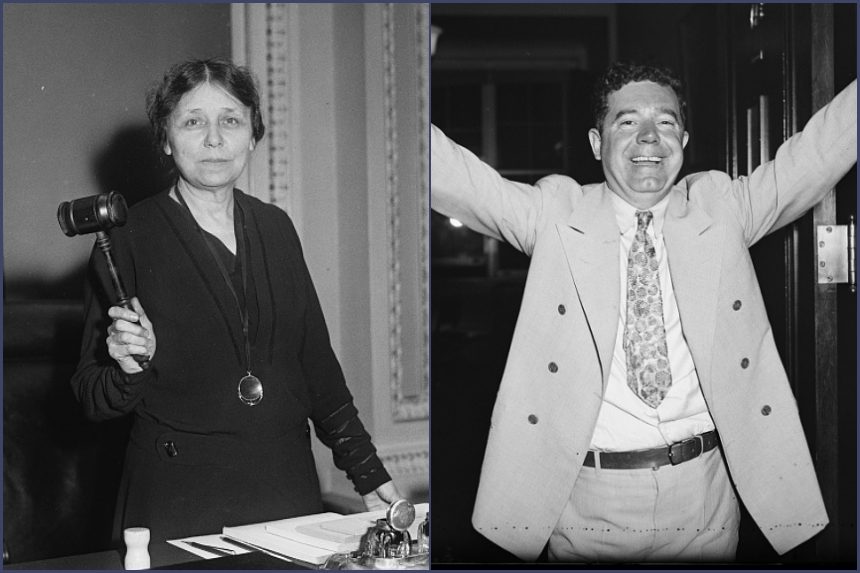

Caraway represented Arkansas in the Senate for 14 years. Her interests were closely aligned with FDR’s New Deal, and she was an early sponsor of the G.I. Bill and the Equal Rights Amendment. In addition to being the first woman elected to the Senate, she was also the first woman to chair a Senate committee, the first woman to preside over the Senate, and the first woman to run a Senate hearing.

Caraway was challenged in 1938 by John Little McClellan, whose campaign motto was, “Arkansas Needs Another Man in the Senate!” She won that election, too.

Her luck ran out in 1944 when she lost to J. William Fulbright, but the point — and history — had been made. As a senator, she rarely made speeches, claiming that she did not want to take speech time away from the men: “The poor dears love it so.”

She may have been known as “Silent Hattie,” but her pioneering accomplishments roared.

Featured image: Hattie Caraway and Huey Long (Library of Congress)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now