This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

One hundred years ago, on January 26, 1922, the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill passed the House of Representatives by a vote of 230 to 119. First introduced by Missouri Representative Leonidas C. Dyer in 1918 but only brought to a vote in early 1922, the bill classified lynching as a federal felony, giving U.S. authorities power to prosecute cases, enforce punishments against not only participants in lynchings but also officials who failed to protect the victims, and force counties where lynchings took place to offer financial compensation to parents or families of victims. Despite the House vote, the support of President Warren G. Harding, and protests in favor of it throughout the year, the bill would be filibustered again and again in the Senate and would never become law.

As we begin 2022’s Black History Month, noting the fate of the Anti-Lynching Bill on the 100th anniversary of its passage helps us better remember progressive allies like Dyer, influential earlier figures like North Carolina Representative George Henry White, and inspiring communities like the Washington, D.C. African American activists who protested in favor of the bill — all of whom are worth celebrating as we begin this month of commemoration.

The history of white supremacist racial terrorism in America is one not simply of violence, but also of how that violence was allowed and even sanctioned by powerful forces at every level of government and society. The lynching epidemic that took the lives of thousands of African Americans and decimated countless communities in the century between the end of the Civil War and the civil rights movement was inextricably linked to powerful governmental figures and forces.

An example of these interconnections can be found in words and actions of Senator Rebecca Latimer Felton. Felton, the first woman to serve in the U.S. Senate, was the wife of longtime Georgia Representative William Felton and a powerful political player in the state and the women’s suffrage movement. Long before Governor Thomas Hardwick appointed Felton to fill deceased Senator Tom Watson’s seat in October 1922, Felton became famous for delivering one of the most vocal and virulent public defenses of lynching. Addressing the Georgia State Agriculture Society in August 1897, Felton proclaimed, “If it takes lynching to protect women’s dearest possession from drunker, ravening beasts, then I say lynch a thousand a week.” This political pioneer who fought for women’s rights and represented a significant symbolic milestone for women in government was from her earliest public roles an impassioned proponent of lynching and maintaining white supremacy at any cost.

A decade after Felton’s brief, symbolic term as senator, Hattie Caraway became the first woman elected to the Senate. Appointed to serve the final year of her late husband Thaddeus Caraway’s term as senator from Arkansas, Caraway then chose to run in and won a special election in January 1932; she would run again in the general election later that year, and with the help of the controversial Louisiana Senator Huey Long would win again. During her total of 13 years in the Senate, Caraway was a consistent advocate for President Roosevelt’s New Deal policies and programs, and in her final term became the first woman to co-sponsor the Equal Rights Amendment. But despite being known as “Silent Hattie,” as she generally refrained from speaking on the Senate floor, in early 1938 she played an instrumental role in a 30-day filibuster by Southern Democrats against another anti-lynching bill, the Wagner-Van Nuys Anti-Lynching Bill. Despite significant support in the Senate, the bill was defeated by Caraway and her colleagues, another example of a groundbreaking political voice working to counter progress on this vital issue.

Indeed, well beyond individuals like Felton and Caraway the Senate as a whole, like the U.S. government more broadly, was dominated throughout the early 20th century by white supremacist figures and forces who successfully stopped any attempts to address and counter the lynching epidemic. The same “Southern Bloc” of conservative southern Democrats and white supremacist Republican allies who filibustered the Dyer Bill throughout 1922 (and did so again when Dyer reintroduced the bill during the 1923 and 1924 sessions, after which he permanently shelved the bill) would continue for decades to filibuster not only anti-lynching legislation, but also, as I traced in my previous Considering History column, countless other civil rights and anti-discrimination bills. Their efforts ensured that no federal anti-lynching legislation was ever passed (despite over 200 attempts across the 20th century), nor any federal response offered to the period’s concurrent, constant racial terrorist massacres like that in Tulsa in 1921.

Efforts to limit and even outlaw the teaching of histories of race and racism, such as those currently sweeping much of the country, thus have far wider-reaching effects than on those particular subjects alone. There’s no way to fully and accurately teach or understand the histories of Congress, American government and law, or 20th century society as a whole without a prominent place for topics such as race and racism. Better remembering the story and fate of the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill offers one case study in all those interconnected threads.

The story of this defeated anti-lynching effort also helps us recognize a series of inspiring figures and moments. There’s Leonidas Dyer himself, a Spanish American War veteran and reformist St. Louis attorney who successfully ran for Congress in 1910 and served until 1933. Representing a majority African American district, and outraged by the 1917 massacres of Black communities in both St. Louis and East St. Louis (an Illinois town just across the Mississippi River), Dyer introduced his first anti-lynching bill in 1918. Noting other recent laws on topics such as child labor and alcohol, Dyer argued, “If Congress has felt its duty to do these things, why should it not also assume jurisdiction and enact laws to protect the lives of citizens of the United States against lynch law and mob violence? Are the rights of property, or what a citizen shall drink, or the ages and conditions under which children shall work, any more important to the Nation than life itself?” In the face of the white supremacist filibusters and opposition, Dyer’s motto remained, “We have just begun to fight.”

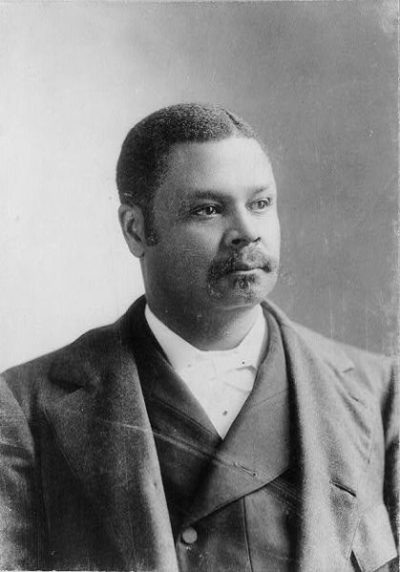

In carrying forward that fight, Dyer was part of a long legacy of anti-lynching activists, including a groundbreaking and far too forgotten earlier Congressman, North Carolina’s George Henry White. Born to a free Black father and enslaved Black mother in 1852 North Carolina, White graduated from Howard University in 1877, became a lawyer and high school principal, and served for many years in the North Carolina House of Representatives. He was also a delegate to the 1880 Republican National Convention, and two decades later would extend that national political service, becoming the only African American in the 55th Congress (1897-1899). He focused his efforts in Congress on civil rights, voting rights, and other recognitions for African Americans (such as a call for President McKinley to honor Black Spanish American War soldiers). After winning reelection in 1898 despite intense opposition, on January 20, 1900, he introduced the first federal anti-lynching bill. As he did so, he made clear that he represented voices from around the country, submitting to the House in February an anti-lynching petition from New Jersey residents. Although white supremacists stalled White’s bill in committee, both it and he deserve our commemoration this month and every month.

Individuals like Dyer and White were complemented in their anti-lynching efforts by inspiring and influential activist communities. In the decade after its 1909 founding, the NAACP focused much of its work on opposition to lynchings, culminating in the April 1919 report Thirty Years of Lynching in the United States, 1889-1919, which provided vital investigative and statistical evidence to bolster the Dyer Bill. And in June 1922, the NAACP and other allies organized a silent protest march in Washington, D.C. in support of the Bill and in opposition to lynching. More than 5,000 African Americans took part in the June 14th march, an expression of communal voice and American activism that offered a vital contrast to the white supremacist solidarity of the Southern Bloc. We can’t teach or remember American history without understanding the interconnections between white supremacy and political power, the alternatives embodied by African American activists and allies, and all the complex and crucial lessons those histories and figures offer.

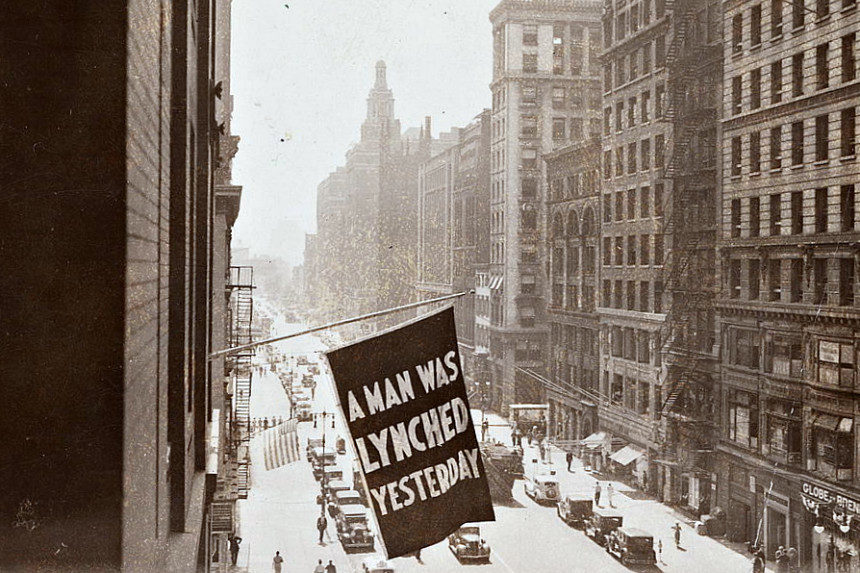

Featured image: Flag flown from the window of the NAACP headquarters at 69 Fifth Avenue, New York, 1936 (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now