Supreme Court Justices have recently given the public assurances that their politics do not influence their judicial opinions. Justice Amy Coney Barrett said, “To say the Court’s reasoning is flawed is different from saying the Court is acting in a partisan manner.” Justice Clarence Thomas added, “I think the media makes it sound as though you are just always going right to your personal preference….That’s a problem. You’re going to jeopardize any faith in the legal institutions.” And Justice Stephen Breyer commented, “A lot of people will strongly disagree with many of the opinions or dissents that you write, but still, internally, you must feel that this is not a political institution, that this is an institution that’s there for every American.”

That verdict is not affirmed by the court of public opinion; according to a recent Grinnell poll, 60 percent of Americans believe the Justices base their opinion more on politics than on law.

That impression was reinforced last year when the Court made a shadow-docket decision on a Texas abortion law. It was the reason, according to a Gallup poll, that the Court’s approval rating dropped from 49 percent to 40 percent in two months.

Should the Court remain aloof from politics? Can it? After all, the Court is comprised of men and women chosen for their judicial opinions, which are based on the same reasoning and values that shape their politics. It is for those the Justices’ reasons and values, as well as their legal knowledge, that presidents nominate them for the Court.

Article III of the Constitution says little about the Justices’ conduct, other than they “shall hold their offices during good behavior.” Nor was anything said about Justices’ politics in the Judiciary Act of 1789 that helped structure the federal judiciary.

Justices must answer for their politics and judicial leanings only during their nomination hearings, when their readiness to overturn precedent is closely questioned by senators.

The senators certainly regard the appointment of Supreme Court Justices as a political act. In 2016 and 2020, the Senate majority first delayed one nominee’s hearing, then rushed another’s to take advantage of election cycles.

Senators (and many others) have long assumed presidents nominate judges to advance their political agenda. It’s the reason why for decades the Senate majority declined to confirm nominees if nominated by a president of the minority party. In 1801, Federalist senators, then in the majority, passed a law eliminating one seat from the Court to prevent incoming President Thomas Jefferson from naming a judge during his term. And in the 1840s, President John Tyler’s eight proposed nominees were turned down because he had no political coalition supporting him in Congress.

Supreme Court Justices themselves haven’t kept clear of politics. John McLean ran for president in every election from 1832 to 1860, all while sitting on the Court, and it was widely known that Chief Justice Salmon Chase was angling to be the Democratic nominee for president in 1868.

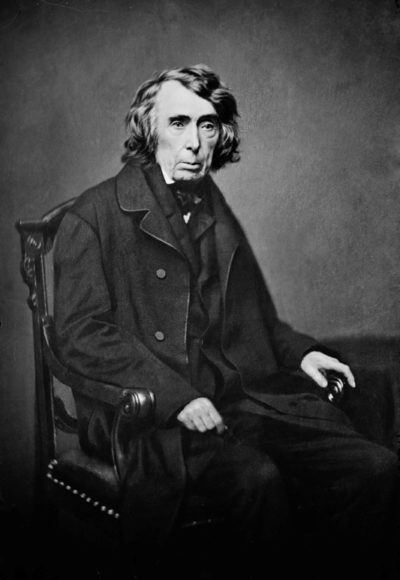

And there have been Justices who actively and unapologetically promoted their politics. Roger Taney, a strong supporter of slavery, openly asserted his belief that the southern states had the right to secede. He blamed President Lincoln for the war, and he ruled against the president’s suspension of habeas corpus and his imposition of a naval blockade of the South — two measures essential to Lincoln’s war efforts.

Many people believed Chief Justice Earl Warren was pushing a political agenda when he expanded civil rights and federal power between in 1953 and 1969. He was instrumental in steering the Court toward outlawing segregation in Brown v. Board of Education. He also supported defendants’ rights in Miranda v. Arizona, which led to the “Miranda warning.”

In 1971, President Nixon nominated William Rehnquist to shift the Court back to the right. Rehnquist consistently reflected conservative thinking in his opinions on reproductive rights, religious expression, free speech, and expanding federal powers.

The political division surrounding nominations became more bitter when Democrats rejected President Reagan’s nominee, Robert Bork. Since then, both liberals and conservatives have tried to gain a majority of Justices on the Court, leading to what SCOTUSblog Publisher Tom Goldstein called “scorched-earth ideological wars over nominations.”

Today, writes Politico’s Jack Shafer, “most Supreme Court Justices come up through partisan politics.” He remarks that John Roberts, Elena Kagan, Neil Gorsuch, and Brett Kavanagh all worked for sitting presidents before they were nominated.

Professors Neal Devins and Lawrence Baum have noted how Republican-nominated Justices invariably tend toward conservativism and Democratic-nominated Justices lean toward liberalism. They write, “Before 2010, the Court never had clear ideological blocs that coincided with party lines.”

David Orentlicher, a UNLV professor and Nevada state representative, writes that the system has strayed far from the checks and balances the founders intended. “The framers did not expect — nor did they want — a Supreme Court that would reflect the views of only one side of the political spectrum.” Under such a system, he writes, with lifetime-appointed Justices, a minority political faction could remain under-represented for entire generation.

Today, writes Professor Rachel Shelden of Penn State, the Court has power that the founders couldn’t have imagined. It enters into important, highly political issues, writing decisions that will have vast impact. And presidents and legislators have been happy to let them, since it enables them to dodge the tough questions.

The use of the emergency or “shadow” docket is one example of how the Court has changed. The shadow docket involves emergency motions and summary decisions by the Court. It is used when the Court believes an applicant will suffer “irreparable harm” if action is not immediately taken. These unsigned, unexplained court orders involve no hearings and offer no reason for decisions. Critics say it enables the Court to act arbitrarily, without accountability, to overturn long-standing judicial policy.

The Court has rendered shadow docket opinions to stay lower court decisions with increasing frequency. Between 2001 and 2016, the Justice Department applied for such emergency decisions just eight times. Between 2016 and 2020, Justice made 41 applications. The Court acted on 28 of them.

Another cause of concern has been “judicial activism,” the ability of the Court to strike down a law passed by Congress that the Justices think is unconstitutional. Critics say this practice violates the principle of “checks and balances.” A decision by the Supreme Court may be considered the final word on a subject because overturning their decision requires the rare act of Congress and the states passing a Constitutional amendment.

Between 2000 and 2019, the Court has held a law — in part or in totality — unconstitutional 86 times. Critics maintain that laws that are passed by the people’s representatives better reflect popular will than the ideas of nine lifetime-appointed Justices with little or no accountability.

Representative Brendan Boyle of Pennsylvania said, “With some Court decisions, conservatives may win. With other decisions, liberals may win. But each time the court takes upon itself the unilateral power to rule on a matter best left to the people, it is democracy that loses.”

Kim Holmes, former vice president of the Heritage Foundation writes, “Let’s face it. Ever since at least the 1960s (and frankly even before) we have increasingly allowed the Supreme Court to decide controversial issues we have been unwilling to solve legislatively. From civil rights to abortion to the issue of gay marriage, the high Court has ruled on key issues well outside the legislative process. New constitutional rights were created out of whole cloth.

“If abortion couldn’t be legalized at the ballot box, or if gay marriage could not be made lawful by Congress or the states, a majority of the Supreme Court — a mere five people — would step in and do it for us. Using the power of judicial review, a new policy would be imposed simply by redefining it as a constitutional right.”

Abraham Lincoln acknowledged the outsized power of the Supreme Court in his first inaugural address. Knowing that he was standing in front of Chief Justice Roger Taney with whom he strongly disagreed, he said, “The candid citizen must confess that if the policy of the Government upon vital questions affecting the whole people is to be irrevocably fixed by decisions of the Supreme Court,… the people will have ceased to be their own rulers, having to that extent practically resigned their Government into the hands of that eminent tribunal.”

A widely discussed solution to bias in the Supreme Court has been to “pack” the Court with more Justices, who could balance its political spectrum. But more political bias might only address the symptom, not the problem.

Other ideas include:

• Placing a limit on Justices’ time on the Court. Chief Justice John Roberts has said, “Setting a term of, say, fifteen years would ensure that federal judges would not lose all touch with reality through decades of ivory tower existence. It would also provide a more regular and greater degree of turnover among the judges. Both developments would, in my view, be healthy ones.”

• Allowing every president to appoint two Justices in their first year in office. Naturally, this would increase the number of Justices, but it would enable all presidents to affect the Court’s makeup. (According to one calculation, the Court would probably expand to 15 Justices over two decades.)

• Appointing Justices from a permanent panel of 180 federal judges, bringing them up from lower federal courts for a few years, then returning them to their former judgeships.

• Limiting jurisdiction. Under the Constitution, Congress can limit the cases over which the Court has jurisdiction.

• Requiring a 9-2 supermajority of Justices to strike down a federal law.

Unfortunately, each of these solutions comes with the same problem: how can Congress pass a law governing the Supreme Court if the Court can rule it illegal? And yet, perhaps the Court will acknowledge its own boundaries. As Justice Elena Kagan said, “The Supreme Court, of course, has the responsibility of ensuring that our government never oversteps its proper bounds or violates the rights of individuals. But the Court must also recognize the limits on itself and respect the choices made by the American people.”

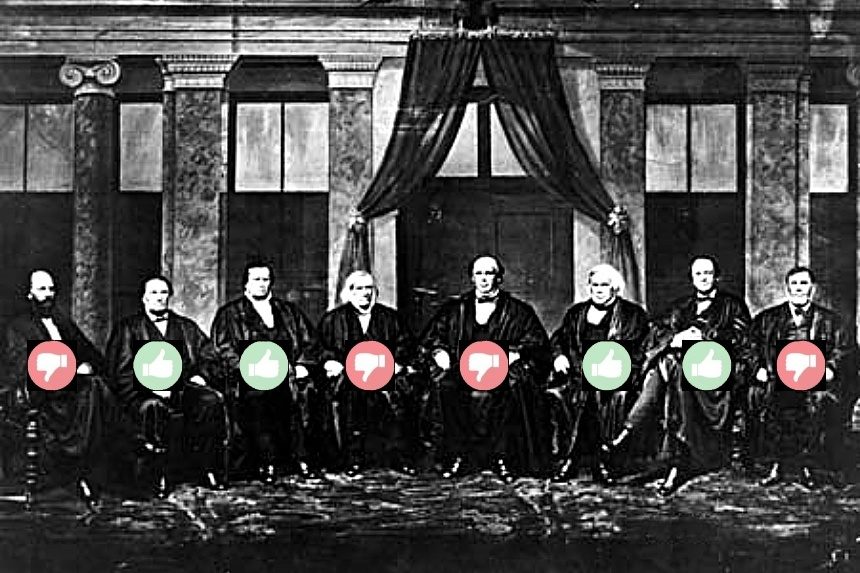

Featured image: First photograph of the U.S. Supreme Court, by Mathew Brady, 1869 (National Archives; illustrations from Shutterstock).

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I assume you’re talking about cases like the Court’s ruling that the legal power of a city to take over someone’s private when it’s for public purposes can also be used to take private property in order to sell it to a private party.

Or the case that overturned decades of law by ruling that police no longer need to have probable cause to make a traffic stop and search a car. They’re now allowed to pull the car over based only on their educated instinct that a crime has been committed.

Or that a corporation has the same freedom of worship as a human being and can use that freedom to deny the freedom of worship of its employees.

Or that the government does not have the right to stop corporations from disposing cancer-causing chemicals in places where they can seep into people’s drinking water.

If you actually read the surveys, you’ll find that the majority of the people who distrust the court are reacting to those kinds of cases, not the “slanted left wing” decisions.

Another one of the left slanted political articles from the Post. When are you people going to learn to remain neutral when it comes to political leanings in your article. Just one more comment.,.the reason the 60% feel as they do about the court is due in large part what the slanted left wing liberal media poisons our minds with they like to pass off as impartial news. It’s BS and nothing more.