The “multiverse” is having A Moment.

Between the critically acclaimed Everything Everywhere All at Once, the blockbuster performance of Spider-Man: No Way Home, the continual crossworld shenanigans on The CW’s “Arrowverse” family of DC Comics-based shows, or even Netflix’s Russian Doll, various versions of the multiverse run rampant in entertainment. This week, the latest installment in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness, opens, and it puts the central conceit of its plot machinations right there in the title. But even though it’s big right now, the concept of the multiverse has been around for decades in both science and entertainment.

The multiverse concept is simple of the face of it. It suggests that for every universe, there is another universe that diverges based on decisions that are made or actions that are taken. If, for example, you missed the bus but met your husband at the bus stop, that’s one level of the multiverse; if you made the bus and you never met, that’s a different level. A multiverse would mean that there are infinite possibilities. While various writers and scientists would have some enormously entertaining arguments about whether separate universes are the same or different from alternate timelines, parallel dimensions, and so on, for our purposes let’s just think of it like this: each universe goes a different way.

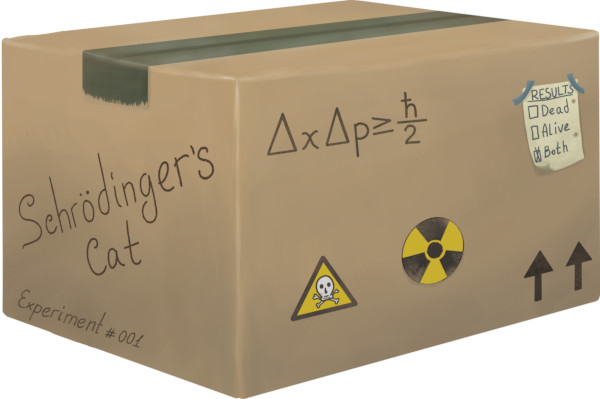

There’s debate about which scientists actually got the ball rolling on current multiversal theories, but we know that both Erwin Schrödinger (yes, the cat guy) and Hugh Everett III were thinking about it in the 1950s. Born in 1887, Schrödinger would grow up to become a brilliant physicist and scientific philosopher. He and Paul Dirac won the Nobel Prize in physics in 1933 for their trailblazing work in quantum mechanics before he left Germany later that year due to the rising danger of the Nazi regime. Two years later, the thought experiment that is widely known as “Schrödinger’s Cat” came out of discussion between Schrödinger and Albert Einstein; it supposes that, in short, a cat in a covered box is either alive or dead at the same moment, unless observed to be alive or dead. Schrödinger gave a lecture in Dublin in 1952 in which he suggested that variations of time could all happen at the same time.

The trailer for Everett documentary, Parallel Worlds, Parallel Lives (Uploaded to YouTube by OfficialEeels)

Three years later, Hugh Everett III got his master’s from Princeton. His 1957 dissertation was called “The Theory of Universal Wave Function.” Central to his work was the idea of the Many Worlds Interpretation (MWI), where every outcome to every event is possible, and could in fact co-exist. In terms of Schrödinger’s Cat, Everett’s theories suggest that all outcomes are true; when you open the box, there is one reality’s outcome that the cat is alive, and another that that cat is dead. All things are true, because, as the 2022 movie proposes, everything is happening everywhere all at once.

In 2019, astrophysicist Ethan Siegel wrote a piece for Forbes titled “This Is Why The Multiverse Must Exist.” After carefully explaining ideas central to quantum mechanics and the theory that the universe is constantly expanding, Siegel concludes, “If you have an inflationary Universe that’s governed by quantum physics, a Multiverse is unavoidable. As always, we are collecting as much new, compelling evidence as we can on a continuous basis to better understand the entire cosmos. It may turn out that inflation is wrong, that quantum physics is wrong, or that applying these rules the way we do has some fundamental flaw. But so far, everything adds up. Unless we’ve got something wrong, the Multiverse is inevitable, and the Universe we inhabit is just a minuscule part of it.”

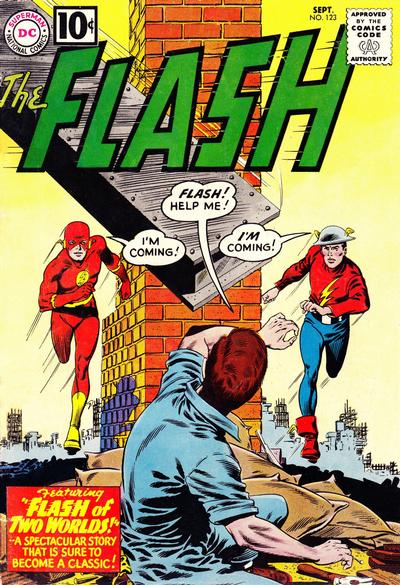

The multiverse concept in fiction was off to the races in 1961 with the publication of The Flash #123 by DC Comics. “Flash of Two Earths!” was an attempt by writer Gardner Fox to reckon with a line-wide reboot that had taken place at the publisher. Around 1949, many of the original versions of DC’s super-heroes had their books cancelled; while Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, and Aquaman kept on adventuring, others like the original Flash, Green Lantern, and Hawkman were retired. In 1954, DC began to unveil new versions of those characters, starting with The Flash. When some fans asked what happened to the original Flash, Fox answered by crafting a tale that the Flashes came from two different universes. In the story, the Barry Allen Flash explains, “As you know — two objects can occupy the same space and time — if they vibrate at different speeds!” That explanation, built on the work of Schrödinger, Everett, and others, laid a new foundation for how DC would operate. Soon enough, all the old heroes would be showing up alongside their newer versions, and the earlier Justice Society would meet their younger counterparts in the Justice League. The younger heroes were said to live on Earth-1, whereas the older versions were from Earth-2.

However, credit for actually employing the term “multiverse” in fiction goes to the British fantasy author Michael Moorcock. In 1962, Moorcock published “The Sundered Worlds” in Science Fiction Adventures. There he employed the storytelling device that has only gotten more familiar in science fiction: one character may exist in a variety of forms in different levels of the multiverse; . Moorcock began building on this with his Eternal Champion character, introduced that same year in the pages of Science Fantasy. Moorcock’s most famous creation, Elric of Melniboné, is part of that broad saga.

A scene from the “Mirror, Mirror” episode of Star Trek (Uploaded to YouTube by CBS)

Though the term multiverse wasn’t used, one of the most widely-known parallel universe stories in popular culture is “Mirror, Mirror,” the fourth episode of Star Trek’s second season from 1967. A transporter incident causes Captain Kirk, Lieutenant Uhura, Doctor McCoy, and Mr. Scott to exchange places with their counterparts from an “evil” universe. The most famous image from the episode is that of the goateed Mr. Spock from the Mirror Universe. The episode remains a highly praised entry in Star Trek canon, and several episodes from the span of Trek shows have revisited it. The “goatee means they’re an evil double” trope has been parodied many times since, most notably on the series Community with the running “Darkest Timeline” gag.

During the 1960s, the multiversal team-ups became an annual event in the pages of Justice League of America. DC had an early cross-media homage to both “Mirror Mirror” and their multiverse air on an episode of the Super Friends cartoon in 1979. “Universe of Evil” saw the good and bad Superman briefly swap places before they were returned to the proper planes. While it took a while for their crosstown rivals, Marvel Comics, to get in on the multiverse-hopping fun, they’d eventually dive in. Marvel Comics’s Earth is designated Earth 616 in their continuity.

The CW’s Crisis on Infinite Earths crossover trailer (Uploaded to YouTube by TV Promos)

While multiverse tales remained a staple of science fiction over the decades (Adult Swim’s wildly popular Rick and Morty, co-created by Community’s Dan Harmon, is probably the biggest example), the various DC shows on The CW would dial it to another level. Arrow debuted in 2012, and spun-off The Flash in 2014. Over the next few years, they were joined by Supergirl, Legends of Tomorrow, Batwoman, and Black Lightning. Several of the series were shown to exist in different universes, but various mechanisms allowed the characters to hop back and forth, interact, and team up. The multiverse widened to the point that it even acknowledged that DC shows from the past (the 1960s Batman) or even streaming services (Titans, Swamp Thing, Doom Patrol, Stargirl) were all part of one big happy multiverse. They even threw down the gauntlet on having characters from seemingly unrelated films, like Ezra Miller’s Flash from the 2018 Justice League movie, appear on a crossover episode of the TV shows.

That brings us to the Marvel Cinematic Universe, which has deployed the multiverse as an extremely clever way to unite various properties that had wound up in other hands over the years. In the ’90s, the media rights to several Marvel franchises went to a number of different companies by a series of options and licensing agreements. Fox obtained the X-Men and the Fantastic Four, Universal had the Hulk, Sony had Spider-Man, and so on. Kevin Feige, who broke in as an associate producer on the X-Men films, was hired by Marvel Studios founder Avi Arad to work on the properties that they could still access. Feige devised what became the blueprint for the MCU by building on solo films for Iron Man, Thor, and Captain America, and then uniting them on-screen as The Avengers, just like in the comics. Do we need to say it worked? It worked.

The Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness trailer (Uploaded to YouTube by Marvel Entertainment)

Over time, Marvel Studios either worked out deals to include the characters with rights at other places (Hulk, Spider-Man, etc.) or ended up re-acquiring them via merger. Along the way, they started seeding the idea of using the multiverse in places like the Disney+ series Loki. Still, the question of how to reintegrate characters like the X-Men and the Fantastic Four has been hanging in the air. That question was answered in part by the Super Bowl teaser for Doctor Strange and the Multiverse of Madness, which made it fairly clear that a certain bald gentleman with a school for gifted students would make his MCU debut in the film. Whereas the DC transmedia multiverse has been a way to expand offerings from the inside-out, it appears that Marvel will be using it to get the whole family in the same place for the first time. Marvel and Sony also collaborate with a mulitversal view in animation; Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse won the Oscar for Best Animated Feature in 2019 and will be generating two sequels and a spin-off.

The Everything Everywhere All at Once trailer (Uploaded to YouTube by A24)

Of course, the multiverse isn’t solely the provenance of franchises. Written and directed by Daniels (the team of Dan Kwan and Daniel Scheinert) and starring Michelle Yeoh, 2022’s Everything Everywhere All at Once manages to be an art film, a science fiction film, an action film, a family drama, and a comedy. One supposes it’s in the name. The film uses the fracturing of possibilities as a way to examine generational trauma and the wreckage in can bring to relationships. Very few films of this nature feature saving the family Laundromat from tax ruination as a prime concern, but that’s part of its brilliance. It shows, both ironically and unironcally, that there are many directions in which this style of story can go.

As for the multiverse’s appeal, mathematical physicist Syridon “Spiros” Michalakis of Caltech’s Institute for Quantum Information and Matter has some ideas. Michalakis was the science consultant for Marvel’s Ant-Man films, so he’s seen the concept from both the scientific and entertainment ends. In an interview with Vox, Michalakis remarked on the idea as a key to possibility, saying, “I want people to know — especially young people trying to figure out where they fit in this world — that they have power to make anything happen, and make that world where they can do amazing things. They can really take control and become that version of themselves that unlocks their true potential.”

Like any cultural force having its moment in the zeitgeist, multiverse stories could fade. Marvel is making it clear that their own multiverse will be quite busy over the next few years, and the return of Michael Keaton to the role of Batman shows that DC isn’t done either. But the defining characteristic of a multiverse might be that it shows you that anything could happen. There’s even a world where physicist Hugh Everett III’s son grew up to be a rock star and appeared in a documentary about his dad (it’s our world). In the long run, maybe the notion of the multiverse is reassuring. Even if you’re having a bad day, know that there’s a version of you out there that’s having a good one, and tomorrow might be your turn.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I think it worth mentioning the film “Rashomon”, which returns to the same event from four different points of view. This concept (along with other films and fiction that borrow from it) is certainly related to the multi-verse idea by suggesting the different realities experienced in just this one universe. I wonder if either multi-versed scientists or fabulists were fans of and influenced by Kurosawa’s classic film.