This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

A couple weeks back, Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito delivered the keynote address at the Notre Dame Law School’s second annual Religious Liberty Summit in Rome. Much of the subsequent attention has focused on Alito’s defense of the Court’s recent Dobbs decision on abortion, and especially his mocking of foreign leaders who had criticized that decision. But Alito’s remarks overall presented a far broader defense of religious liberty, which he defined throughout as under sustained attack from “our increasingly secular society.” He argued that there’s “growing hostility to religion, or at least the traditional religious beliefs that are contrary to the new moral code that it is ascendant in some sectors.” And he equated religious liberty with the necessary special protection of religion and religious communities from these attacks.

A sitting Supreme Court Justice delivering such pointed social and political commentary publicly seems a bit unusual (although it is far from unheard-of). But Alito’s remarks fit smoothly into a longstanding, indeed a defining, American debate. Religious liberty is one of America’s founding ideals, a quite literally revolutionary guarantee that any and all religions (including no religion) would be included and equal in this new nation. But in practice, far too often religious liberty has meant the freedom to equate the nation with Christianity and discriminate against and exclude those who are outside that perspective and community.

Both sides of that coin can be found in the story of one of the earliest European American communities, the New England Puritans. The Puritans made their way to the Americas in search of religious freedom, fleeing the persecution they and their extreme form of Protestant Christianity had faced in both England and Holland (as it was then known) and hoping to build a new community where they could practice that religion in peace. What Puritan lawyer and leader John Winthrop famously referred to as the “city upon a hill” in his 1630 speech “A Model of Christian Charity” was the idea that the world would be watching what happened with this community now that it would be finally free to practice and amplify those religious beliefs.

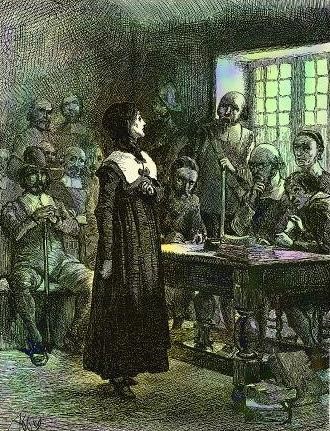

The Puritans immediately began to oppress and expell anyone who did not conform rigidly to those religious beliefs. The most famous such case was that of Anne Hutchinson, a Puritan woman whose unorthodox, dissenting perspective on Christianity led her to be put on trial (by John Winthrop himself, among others) and ultimately banished entirely from Massachusetts. But just as striking was the case of Roger Williams, a leading figure in mid-17th century Puritan New England who simply sought to separate the church from the colony’s government and became just as much of an outcast as Hutchinson, forcing him to leave Massachusetts and found the new colony of Providence, Rhode Island. For the Puritans, religious liberty only applied to those who fully adhered to their religion, which shaped their community and government just as much as their everyday lives and identities.

When the Framers created a new government and nation in the aftermath of the American Revolution, they clearly established the more inclusive version of religious liberty as a founding ideal. I wrote at length in this Considering History column about the most radical element of the U.S. Constitution: the establishment of a national government that not only had no state religion, but that also explicitly forbid the idea of religious tests for anyone seeking to be part of that government. When asked during the North Carolina ratification debate whether that clause meant that “pagans, deists, and Mahometans might obtain offices among us,” the Constitution’s advocate James Iredell responded that it would indeed; “how it is possible to exclude any set of men,” he asked, “without taking away that principle of religious freedom which we ourselves so warmly contend for?”

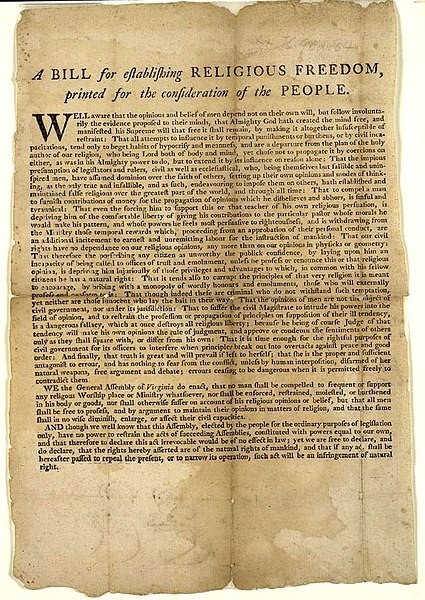

In the same moment that the Constitution was being drafted, Thomas Jefferson went even further with an attempt to establish and protect such inclusive religious liberty. Jefferson’s 1786 Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom guaranteed that all Virginians “shall be free to profess, and by argument to maintain, their opinions in matters of religion, and that the same shall in no wise diminish, enlarge, or affect their civil capacities.” That statute was one of three achievements Jefferson wanted memorialized on his tombstone, along with the Declaration of Independence and his 1819 founding of the University of Virginia, the nation’s first secular public university and thus another community where religious liberty meant including all beliefs.

The Constitution and such laws clearly established a nation defined by legal as well as civic religious freedom. But in practice, those who have fought for “religious liberty” have far too often extended the Puritan legacy instead, working to protect particular religious beliefs and exclude those who fall outside their vision. That trend began in the Revolutionary and Framing eras themselves, not only in formerly Puritan Massachusetts (which allowed only Christians to hold public office, and required Catholics to renounce papal authority before doing so) but in other states like New York (which banned Catholics from voting in its first state constitution) and Delaware (which required in its first constitution an oath from all would-be office-holders professing their belief in the Trinity).

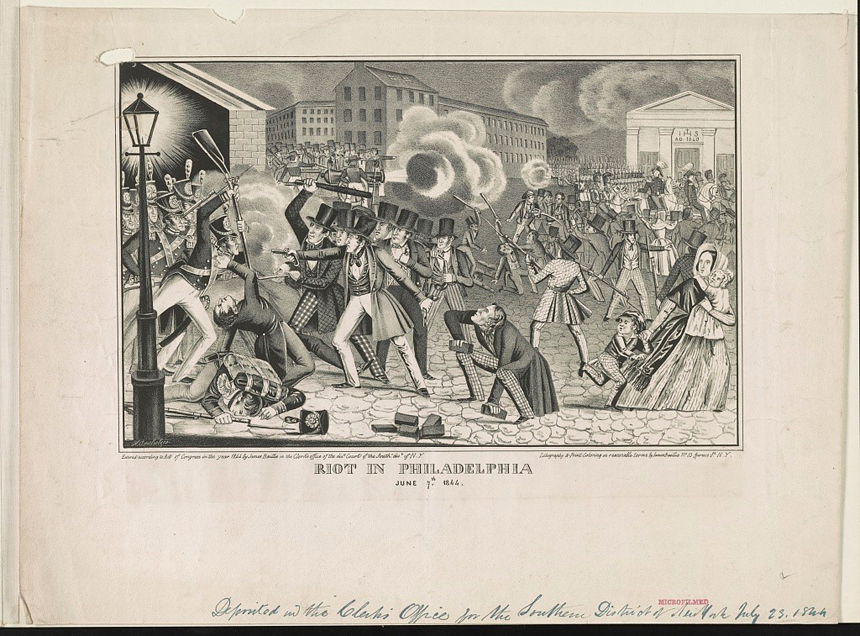

Over the two-and-a-half centuries since the Revolution, “religious liberty” has become a frequent battle cry for those seeking to oppress and exclude beliefs and communities outside of the generally dominant strains of Protestant Christianity. Anti-Catholic “loyalty oaths” have been part of numerous state governments, and views of Catholicism as a threat to American freedoms contributed directly to events like the nativist, violent 1844 “Bible Riots” in Philadelphia. Prejudices against Native American spirituality led to the centuries-long attempts to wipe out indigenous religious beliefs, whether through the boarding school system or massacres like those in the 1890s Ghost Dance War. And atheist Americans have frequently been attacked as fundamentally un-American, including throughout the Cold War when atheism was consistently linked to treasonous sympathies for the Soviet Union, as in President Ronald Reagan’s famous 1983 “Evil Empire” speech.

In the 21st century, “religious liberty” laws have become even more overtly defined by the protection of exclusionary practices motivated by religious beliefs. Such laws have protected the rights of businesses and individuals alike to discriminate: against LGBTQ Americans seeking to adopt children or purchase a wedding cake; against consumers seeking to purchase birth control and against employees seeking health care coverage for it; against public colleges seeking to limit religious proselytizing or discrimination on their campuses. Over the last few years, the Trump Administration worked, through the newly established Religious Liberty Task Force, to solidify these individual laws and cases into an overarching policy goal of protecting the ability of Americans to discriminate and exclude based on their religious beliefs — including the federal government’s own ability to exclude through a policy like the Muslim Ban.

Here in 2022, as with so many foundational American ideas and ideals, the meaning of “religious liberty” remains contested, part of the longstanding but evolving battle between exclusionary and inclusive visions of our community and identity, our history and future. Whether we extend the legacy of the Constitution’s guarantee of inclusion or the Puritans’ practices of exclusion is up to not only the Supreme Court and the federal government but also and especially all of us.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Thanks for the comments and conversation, all. I’m usually fine with letting those conversations unfold without me, hoping that my columns will speak for themselves. But I need to say this:

Balance is absolutely a central goal of mine in every column, along with nuance and accuracy. Highlighting the complexities, the layers, the worst and best of our histories and stories. Trying to help us engage with all those sides to who and what we’ve been and are.

I believe this column achieves those goals. And I think it’s very telling, very frustrating, and very very sad that to some commenters doing so seems “left-wing” or “extreme.”

Thanks,

Ben

I have to agree with Mike Mayak’s comments. A balanced article on a hot potato topic in these divided times is something the Post continues to do very well both online and in the magazine. It isn’t easy, but worth it. Thank you.

“in fact” I mean.

My applause to you for running such an honest article in such divided times when religion (which has nothing to do with any devout faith) is being used against people. There is a lot of misinformation being spread about our history these days, if fact misinformation is a cottage industry!

As usual, left slanted perspective on the subject. I have concluded that over the years as almost everyone who attends (schools of higher learning) are not aware of their left leaning views of the world. The Biblical/actual Christian view requires that faith/must be completely voluntary. Any type of coercion or discrimination is really against truly Christian ideals.

What a dishonest article!

The Founders whom Mr Railton correctly celebrates would have thought same sex “marriage” madness, and lawsuits against bakers whose consciences prohibited their baking cakes for gay “weddings” the farthest reaches of madness. Mr Railton knows this, of course. His is, as I said, a dishonest article.

Mr Railton and his kind would compel such bakers to bake cakes for homosexual “weddings.” So much for the rights of conscience.

And we watch as yet again, The Saturday Evening Post makes an assertive move to hasten its slide into oblivion with yet another genuflection to Wokeness. Wokeness may, in some of its manifestations, be in the ascendancy ( 70% support for same sex “marriage” ), but it will never find favor with the kinds of people who might want to read the newsletter and the magazine. If you acknowledge that 100,000,000 Americans are Woke – resistant ( here’s the secret, Mr Railton: we hate it ), and that to queer the possibilities ( har har ), perhaps 2% of that number might be interested in the Post, we have in view the possibility of 2,000,000 subscribers to a Post which is averse to trendy moral rot and spiritual lunacy.

And yes, I queered the percentage. It occurs to me that maybe as much as 10% of that 100,000,000 might be interested in the Post which we backward types love. Ten million people. Has the Post got ten million subscribers? 1% of that?

It’s sad. But there will always be people who love the good, the true, and the beautiful, and the hope for most of us is in the sureness of the return of the Lord Jesus Christ. Blessed hope, indeed!

Fantastic collection of historic photos.

Very educational!

Another liberal, left slanted article based on more opinion than fact. I am a Christian. We do not exclude anyone from attending our church. We might dislike the sin a parishioner does but we embrace him or her. This goes for anyone who wishes to attend. On abortion…..Plain and simple….The unborn child has a right to live too. To cut down on unwanted pregnancies, one can do any number of things including using protection (condom, pill, etc.) or just plain abstain from having sexual relations with someone you barely know. It might go a long way on cutting down on sexually transmitted diseases too. Our world is in moral decay and your article just backs up that claim.