This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

The movement to reframe and reimagine Thanksgiving through the lens of Native American perspective as a National Day of Mourning remains far less prominent than the largely successful recent efforts to change Columbus Day celebrations to commemorations of Indigenous Peoples Day. The difference is understandable: for one thing, Thanksgiving for many Americans has personal and familial meanings that have nothing to do with national history; and for another, the story of Thanksgiving itself has generally been framed as one that includes both European and Native Americans in a far less divided and more inspiring narrative.

As I wrote in my first Thanksgiving piece for this column four years ago, that traditional story, while oversimplified to be sure, does indeed reflect the presence and role of Native American figures like Tisquantum and Massasoit alongside those of the Puritans at “the first Thanksgiving,” the 1621 harvest festival in Plymouth. But a far more recent Native American voice and perspective from Plymouth, that of the Wampanoag leader Wamsutta (Frank) James at his 1970 Thanksgiving speech in the city, lets us better understand the concept of a National Day of Mourning.

Born in 1923 as part of the Aquinnah Wampanoag tribe on Cape Cod, Frank James was from a young age a fisherman and sailor, a draftsman and builder, and a multitalented artist. He was particularly gifted as a trumpet player, and in 1948 became the first Native American graduate of the New England Conservatory of Music (as well as the first non-white member of the Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia fraternity). When racism denied him the chance to find a position with a symphony orchestra, he returned to Cape Cod, teaching music in multiple schools before serving for decades as the Director of Music for the Nauset Regional Schools. Over this time he also became known more by his chosen name of Wamsutta, a tribute to the historical Wampanoag leader and brother of the powerful but tragic Chief Metacomet (King Philip).

That name change reflected James’s increasing prominence as a Wampanoag and Native American leader, but it was at the 1970 Thanksgiving celebration in Plymouth that he fully embraced that role. James had been invited to speak at the gathering, a commemoration of the 350th anniversary of the Mayflower voyage and the founding of Plymouth colony. The organizers asked to see James’s speech before he delivered it, and when they read his impassioned and righteous critique of the Pilgrims and the treatment of the Wampanoag and Native Americans, they demanded that he revise the speech. Instead, on the night of the gathering James and a group of supporters walked to Plymouth’s Cole’s Hill, near the statue of the Wampanoag leader Ousamequin (also known as Massasoit, who was Wamsutta and Metacomet’s father). There James delivered the full text of his suppressed, stunning speech.

The speech is well worth reading in its entirety, but here I’ll note three interconnected and equally striking layers. First, responding to the gathering’s historical anniversary, James dedicates much of his speech to offering an importantly revisionist history of Plymouth, New England, and early America, one that parallels (but predates by five years) the argument of Francis Jennings’s groundbreaking scholarly book The Invasion of America (1975). Second, he makes the case, “with a heavy heart that I look back upon what happened to my People,” for reframing not just the Mayflower anniversary but also the Thanksgiving holiday through a Native American perspective as a National Day of Mourning. Third, he closes with a more forward-looking, activist vision of what the occasion can mean in the future: “We the Wampanoags will help you celebrate in the concept of a beginning. It was the beginning of a new life for the Pilgrims. Now, 350 years later it is a beginning of a new determination for the original American: the American Indian.”

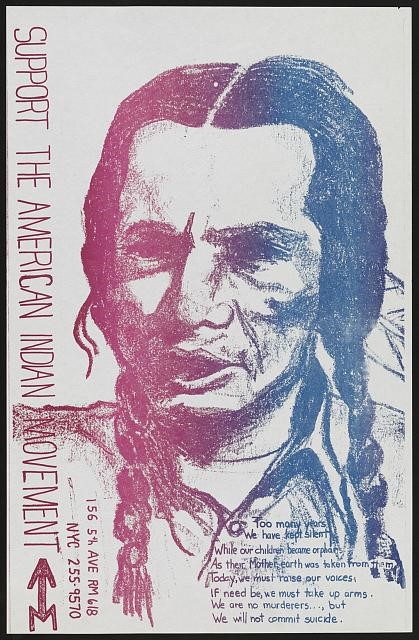

James immediately built upon that closing, activist vision. After delivering his speech he founded a new progressive organization, United American Indians of New England (UAINE), which would organize subsequent National Day of Mourning protests in Plymouth and also take part in activist efforts around the country alongside groups like the American Indian Movement (AIM). James himself was a leader in many of those efforts, including the 1972 Trail of Broken Treaties takeover of the Bureau of Indian Affairs building in Washington and the 1978 Longest Walk march from California to Washington. Those contemporary protests are interwoven with the National Day of Mourning, which James envisioned as linking memory to action, a way to tie the past to progressive efforts that could reshape the present and future in more equitable ways.

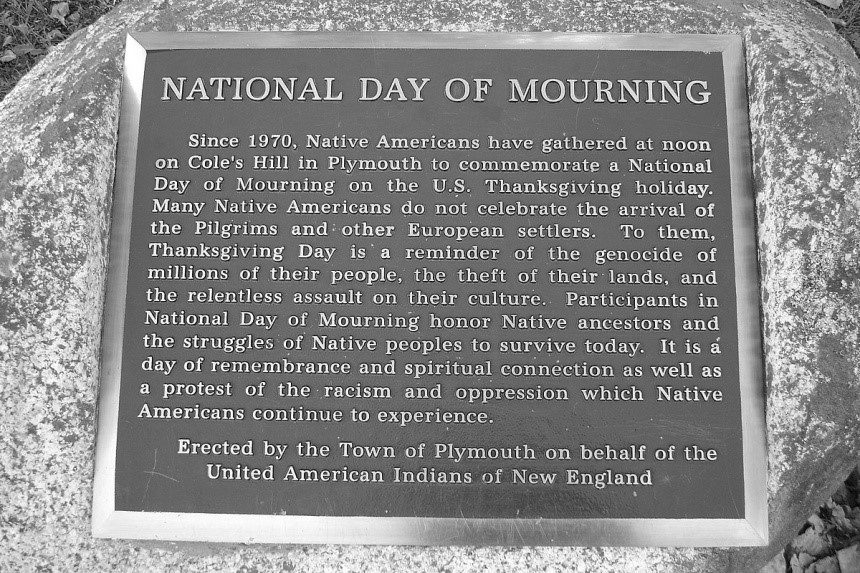

James passed away in 2001 at the age of 77, having served his school district, the Wampanoag tribe, UAINE, Native American communities, and all his fellow Americans with passion and courage for many decades. His legacy lived on with his son Moonanum (Roland) James, who took over organizing the National Day of Mourning protests until his own passing in 2020. And its lives on today in a plaque on Plymouth’s Cole’s Hill which pays tribute to both the 1970 speech and those ongoing protests, noting, “Participants in National Day of Mourning honor Native ancestors and the struggles of Native peoples to survive today. It is a day of remembrance and spiritual connection as well as a protest of the racism and oppression that Native Americans continue to experience.” As we gather this week for holiday celebrations, may we all remember and connect with the life and legacy of Wamsutta James as well.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now