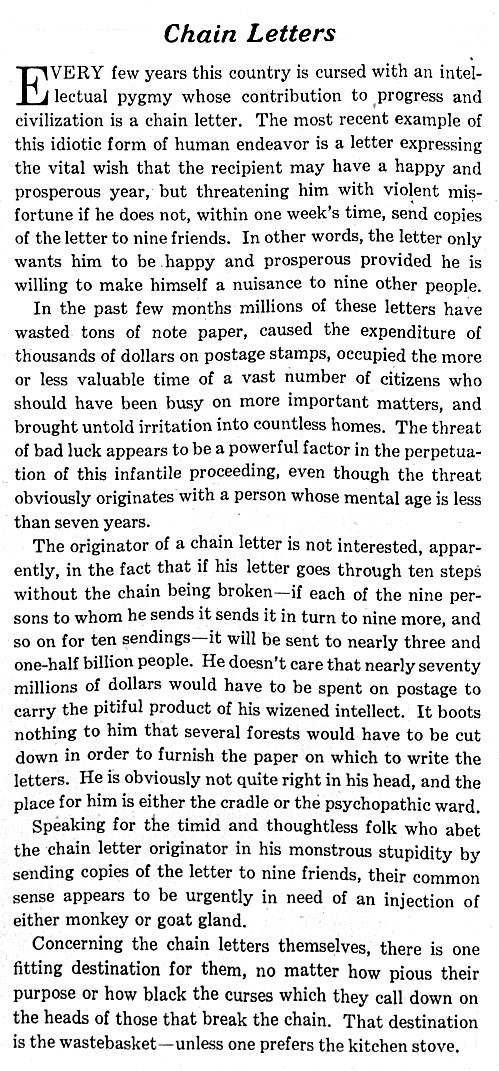

One hundred years ago, a Saturday Evening Post editor was sharing his irritation at receiving a new chain letter. Its author had wished him a happy and prosperous year, but threatened him with violent misfortune if he didn’t send copies of the letter to nine friends within seven days.

The originator of a chain letter, the editor continued, hadn’t considered that, if his letter went through ten iterations without the chain being broken, it would involve over half the people in the world, cost the 2022 equivalent of $1 billion in postage, and level several forests to provide the paper.

The editor wasn’t alone in his annoyance. Chain letters had already been circulating in America for 40 years. Not only did they require people to impose on their friends by passing the letter on to them, but many asked for money as well.

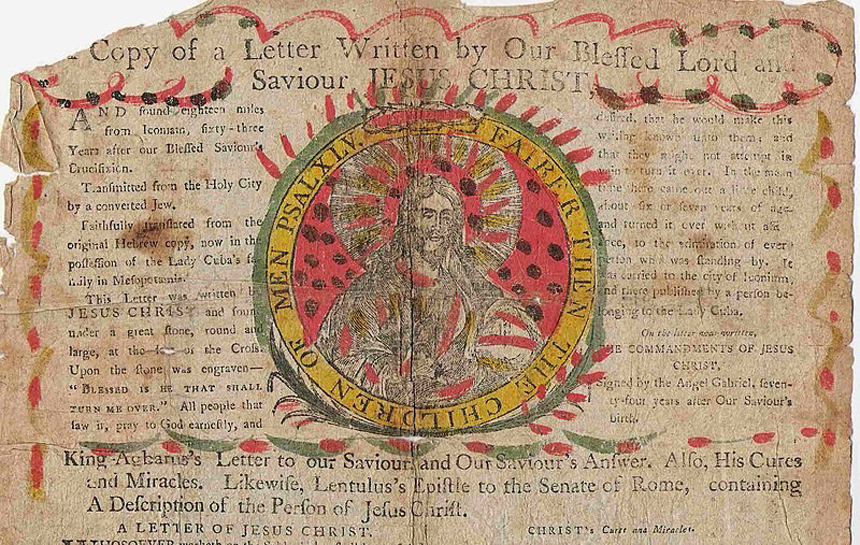

The idea dates back at least to 1795, with a letter purportedly written by Christ Himself. A copy of the letter was printed in London that year. The text — in English and not Aramaic — told readers to keep the Sabbath holy and dress modestly. What made this epistle a chain letter was its threat: “He that copieth this letter shall be blessed of me. He that does not shall be cursed.”

The earliest examples of modern chain letters came out of Chicago in 1888. Mrs. George O. Haman sent out a letter requesting the recipient to mail back one dime with the names of four friends whom Mrs. Haman could also petition.

The money, said Mrs. Haman, would be spent to “educate the poor whites in the region of the Cumberlands, who have so long been neglected and [whose] parents are unable to pay their tuition and without aid they must grow up in ignorance.”

That same year, Lucy Rider Meyer mailed out 1,500 chain letters, asking recipients to send her a dime and spend an additional 8¢ forwarding the letter to three friends. According to In Their Time, Lucy received 200,000 responses and raised $10,000, which was used to build the Chicago Training School, a women’s Methodist missionary school and the largest school of its kind in America.

In 1898, young Nathalie Schenck received national attention for her chain letter. She asked recipients for money to send ice to Americans troops stationed in Cuba. It was the right request at the right time. Her letter drew 3,500 donations, which overwhelmed the little post office in her home town. Nathalie’s mother issued a plea to stop sending more, according to Slate. “We did not consider what patriotic Americans are capable of,” the girl’s mother told the press.

Nathalie’s idea worked so well, a woman in Indianapolis suggested the federal government could use a chain letter to pay down the national debt.

In 1906, a prayer by a “Bishop Lawrence” was sent out as a chain letter. He recommended the receiver rewrite it and send it on to another nine people. Those who didn’t comply would meet with misfortune. “One person who failed to pay attention to it met with a dreadful accident,” he warned.

Chain letters promising luck circulated widely during World War I. The post office handled so many of these letters that the New York Times claimed they were part of a German plot to overwhelm America’s postal system.

In the 1930s, chain letters became a popular medium for pyramid schemes. The best known was entitled “The Prosperity Club.” Begun in Denver, Colorado in April 1935, it proved extremely popular with Americans suffering through the Depression.

Recipients were asked to send ten cents (equal to about $2 today) to the person at the top of the letter’s list, then cross off that name and add their own name and address at the bottom. They were then required to pass along the letter to five new candidates.

“In turn when your name reaches the top of the list,” The Prosperity Club promised, “you will receive 1,625 letters with donations amounting to $1,562.50.”

News of the chain letter led eager participants to buy copies from brokers working out of rented offices or store fronts. In Iowa, for example, brokers for a one-dollar “Dubuque Prosperity Club” opened a storefront operation on Main Street in that city. Within an hour, police shut it down. It reopened the next day, but was closed by the chief of police. A few hours later, the brokers renamed themselves the “Key City Prosperity Club.” This time the police promised to arrest the operators if they didn’t shut down for good.

As the days passed, participants found it increasingly hard to get others to buy in. Almost everyone they knew was already participating. In Springfield, Missouri the chain-letter business had been so busy, residents soon realized almost everyone they knew had a letter to sell.

In April of 1935, 67,000 chain letters passed through the Denver post office in one day.

Despite rumors of some people receiving fantastic sums, there was good reason to believe that the letters wouldn’t pay off. Yet buyers were enchanted by the idea of getting so much money with nothing more than a dime. The scheme finally collapsed; there was no one left to send letters to.

In 1978, the “Circle of Gold” chain spread across the country from California. Participants paid $50 to join and sent another $50 to the person at the top of a list of 12 names. They then crossed off that name, added their own to the bottom, and sold two copies for $50 each. Having recovered their initial investment, they waited for their name to rise to the top of the list. If the chain was unbroken, they were told, their return would be $100,000. And trouble with the law was avoided because the chain relied on hand delivery instead of the postal service.

The Circle of Gold appears to have lasted more than a year. A New York Times article from December 17, 1978, reported “A ‘Gold’ Chain Letter Has Come Full Circle, With a Trail of Victims,” but the Washington Post reported it was just hitting D.C. in July of 1979.

Chain letters made an easy transition to the web in the 1980s. Early web users found emails from strangers directing them to send their message to a number of friends or face a terrible fate.

As late as November of 2015, a large chain letter campaign was conducting a gift-giving pyramid scheme. Promoted as the “Silent Sister” chain on Facebook, it required you to send a $10 gift to the person at the top of the chain’s list and recruit six friends to join. Ultimately, according to the notice, you’d receive 36 gifts.

As usual, authorities warned that such an arrangement is illegal if it involves money or items of value. And mathematicians gladly proved that the system wouldn’t work. According to a Washington Post article, in order for the chain to operate for two weeks, every person on Earth would have to participate eleven times.

Americans know the unlikelihood of profiting from chain-letter schemes. But as a Washington Post reporter put it, “these schemes feel like so little of an investment — just a $10 gift! — that those who think about participating don’t feel too swindled when it doesn’t work.”

The annoyance isn’t with the long odds of money- or gift-exchange chain letters. It’s the intimidation from their threats to chain-breakers and the need to impose on friends. As the Post editors wrote in 1922, chain-letter writers just wanted you to be happy and prosperous — provided you were willing to make yourself “a nuisance to nine other people.”

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Chain letters, a nightmare going back to the late 18th century we’re still dealing with today? Of course we are, thanks to pooh-pooh head social media like Facebook (hopefully on its way out) lowering it to new new lows. The 1922 editorial above says it best, in no uncertain terms.

People with a mental age of about 7 years old. Make that 2 or 3 years now in these brain dead, completely divided hopeless times. A chain letter written by Jesus Christ himself? “He that copieth this letter shall be blessed of me. He that does not shall be cursed.” Outrageous but not surprising, unfortunately. No doubt chain letters will never go away, taking new forms.