America is experiencing a labor shortage. There are currently 10 million job openings, but only 6 million unemployed people to fill them.

As solution to the shortage, some legislators are considering loosening labor laws to make it easier to employ children. A proposed Minnesota law would let construction firms hire 16- and 17-year-olds for their crews. Iowa recently passed a law that allows 16- and 17-year-olds to work in areas such as manufacturing. In March, a bill was introduced in the U.S. House and Senate to allow 16- and 17-year-olds to work in certain mechanized operations in the logging industry “under parental supervision.” Arkansas passed a law that ends a state requirement to verify the age of workers under 16.

Critics regard these measures as a giant step back into some of the worst aspects of 19th century America.

For most of history, adults looked on children as domestic help; they were expected to do chores around the house when young and to work in the fields as they grew older. Parents believed it was important to accustom their children to labor and prevent them from becoming paupers. Also, it was economical; until the 19th century, most families couldn’t afford to raise a child to adulthood without the youngsters contributing to their keep.

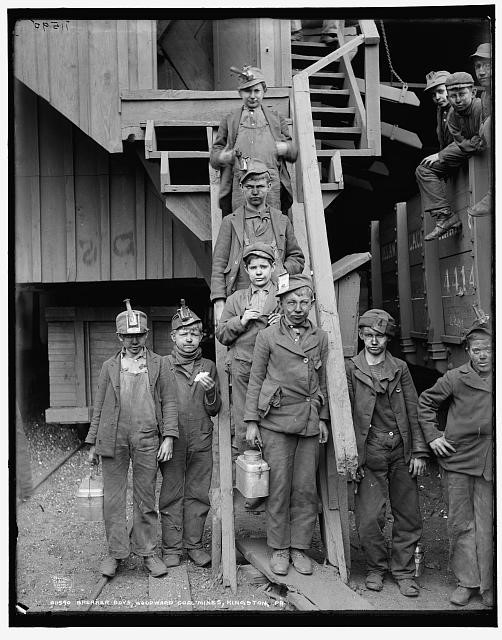

But the nature of work changed with the industrial revolution. Manufacturing was now performed by machines that even children could operate. This was particularly true in southern cotton mills. In 1904, 25 percent of all mill workers were children, and almost half were under the age of 12. And in Pennsylvania, 14,000 children used machines to sort coal.

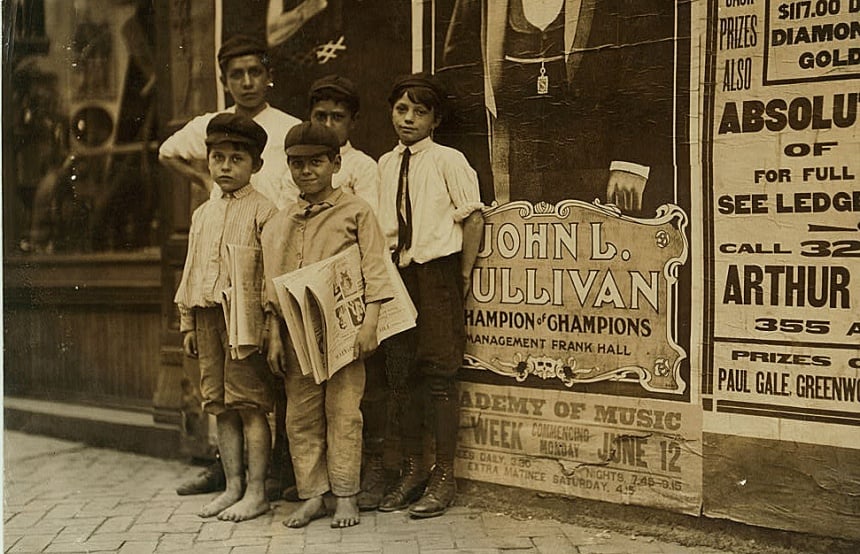

There were still plenty of low tech jobs. In cities, boys and girls stood on street corners hawking newspapers up to 12 hours a day, 7 days a week. Employers believed these hours would leave them no time to spend “in idleness or vicious amusements.”

Journalists reported how dangerous work was to children. Mine workers under age 16 were three times more likely to die than were adults. And 75 percent of the coal sorters who were killed were children under 16.

Doctors were now documenting how child labor was associated with poor growth, malnutrition, higher incidence of infectious and system-specific diseases, behavioral and emotional disorders.

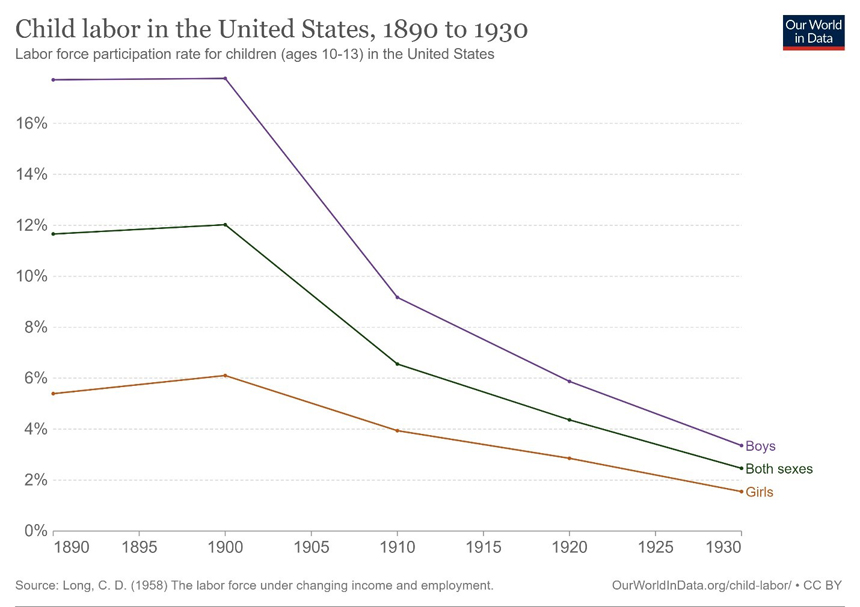

A rising standard of living in the new century reduced the demand for child labor. And reformers of the Progressive Era raised public awareness of how children growing up on the job got little education, leaving them fit only to remain at their job indefinitely.

Starting in the early 1900s, some parents with comfortable incomes could now afford to allow their children a childhood. They no longer viewed their offspring as little adults. Instead, childhood was a time to learn, grow, and prepare for a career.

The first federal bill to end child labor was introduced in 1906. Senator Albert J. Beveridge, its sponsor, said, “We cannot permit any man or corporation to stunt the bodies, minds, and souls of American children. We cannot thus wreck the future of the American Republic.” But child labor laws that eventually passed in 1916 and 1918 were both overturned by the Supreme Court for being unconstitutional. In 1924, Congress passed a Constitutional Amendment on child labor, but it stalled during the ratification process.

Even without the laws, demand for child labor diminished over the next two decades. Many jobs that once went to children had been taken over by immigrants.

In 1938, Congress passed the Fair Labor and Standards Act, which ensured young people would be safe at work, and wouldn’t jeopardize their health, well-being, education, or future. However, it ended child labor for only 6 percent of the 850,000 children working in 1938. It didn’t affect children working on farms or bowling alleys or performing delivery or messenger services. But the law was amended in 1949 to extend the ban, and included jobs in transportation, communications, and public utilities.

Today, child labor is returning surreptitiously with the employment of unaccompanied migrant children. Hannah Dreier of the New York Times found 12-year-old roofers in Tennessee and Florida, minors working in slaughterhouses in three states, and kids operating sawmills on overnight shifts. These children, she says, are being hired for “some of the most punishing jobs in the country.”

Critics oppose the relaxing of child labor laws. They don’t want to see long discarded employment practices returning and are particularly troubled by a feature many of these new laws would include: employers’ exemption from liability from underage workers’ accidents. As Reid Maki of the Child Labor Coalition told NPR, “it’s as if they know that kids are going to get hurt.”

There’s no simple solution. Immigrant children and their families benefit from their wages. And putting children in factories, fields, and slaughterhouses will reduce the labor shortage. But it shortchanges the kids, who sell their brief childhoods at a bargain price. And it’s probably only a temporary fix; sooner or later employers will have to offer the sort of wages that attract adult workers in a competitive market.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

It’s crazy that the kids under 16 and 17 years old have been dead from mining too much. I feel bad for them.

It’s going to be bad for children just like it was a century and longer ago all over again if some of the laws are ‘relaxed’. Per the 2nd paragraph, 16 and 17 year olds are largely a different story than the young children seen in several of the photos above. The potential for abuse is there. Give an inch, take a mile.

The graph (1890-1930) showing the decline of child labor shows it really starting in 1900 which was a good thing. The top photo (1909) shows the boy on the right with no shoes on at that textile machine. Same with the two girls at the cotton mill, and the two boys in front selling newspapers, both from 1911. Very disgraceful, unhealthy and dangerous for these children, and so many others that had no voice or say in the matter.

Unfortunately this topic is timely again now. Add child labor to a long list of trends in the 21st century that are a return to the 19th, skipping over the progress made during most of the 20th.