This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

This week the Major League Baseball All-Star Game and related festivities will be held at T-Mobile Park in Seattle. Besides the obvious sports stories, baseball’s rotating All-Star Game also draws our attention to the many different host cities and what they can reveal about American history. Many of us associate Seattle with the seemingly constant rain, the 1980s and ’90s grunge subculture that birthed some of the most important popular music of the last few decades, and a certain hugely successful and influential romantic comedy.

Long before those late 20th century contexts, however, the 19th century founding of Seattle represented an important step in the expansion of the United States across the full continent. That 1850s founding, and the city’s evolving story over the next few decades, featured some of the worst of white supremacist violence and exclusion. But three iconic figures in the city’s early history embody more inclusive and inspiring stories for Seattle and America alike.

In late 1851, multiple groups of Anglo American explorers and settlers made landfall near the mouth of the Duwamish River in the western region of modern-day Washington State. A traveling party led by farmer Luther Collins arrived on foot and formally claimed hundreds of acres on September 14, 1851; about two months later, a competing party led by Illinois businessman Arthur Denny landed on a schooner that had sailed from Portland, Oregon and staked their own claim. The Collins party remained in their original landing spot of Alki Point and dubbed their new community Alki; the Denny party relocated across Elliott Bay to a spot they christened Duwamps. After a few years of uneasy coexistence between the two settlements, Alki was abandoned and its inhabitants joined Duwamps, the site of present-day Seattle (a name change to which I’ll return shortly!).

As with virtually every European American settlement and city in the Western United States, that growth depended on acts of violent aggression against Native American inhabitants. While much of that aggression took the form of constant land theft, it likewise featured more direct and brutal attacks on Natives. Some of those attacks were individual lynchings, like Luther Collins’s July 1853 murder of the Native American man Masachie Jim under the unsubstantiated pretense that Jim had assaulted Collins’s wife; Collins and those who abetted his crime were brought to trial but acquitted. And some attacks were far more systemic, such as the multi-year Puget Sound War (also known as the Yakima War) that culminated in the January 1856 Battle of Seattle, a conflict in which the settlers were supported by the U.S. Navy warship Decatur. That battle left nearly 30 Native Americans dead, many more wounded, and the region’s Duwamish and Suquamish tribes far more powerless to resist the European American community’s continued growth.

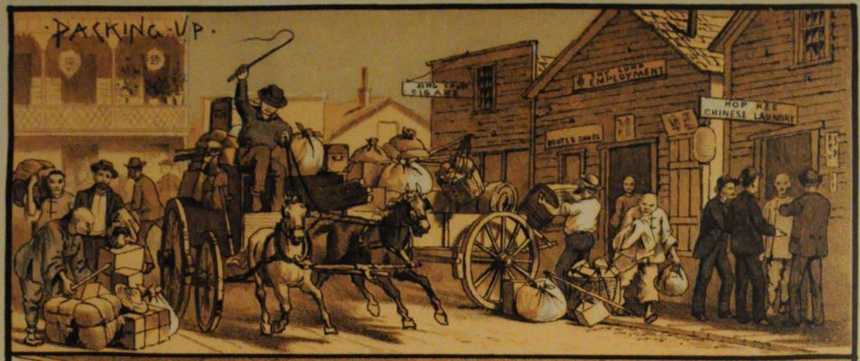

As that growth continued, Seattle became home to another sizeable non-European community: Chinese Americans who had moved into the region in the aftermath of the Gold Rush. That community grew gradually but steadily from the 1860s on, and by the early 1880s numbered more than 500, a significant percentage of the city’s overall population of around 3,500 (per the 1880 census, which documented more than 3,100 Chinese Americans in Washington overall). That community’s size and longevity did not allow it to escape white supremacist prejudices and violence, however, and in February 1886 those trends exploded into a multi-day race riot. Organized by the Knights of Labor, the working-class labor union that too often targeted non-white workers through such riots and massacres, the Seattle Riot of 1886 led to the expulsion of more than 350 Chinese Americans from the city and the widespread destruction of its Chinatown neighborhood.

There’s no way to remember the history of Seattle without including those exclusionary attacks. But there are also figures that reflect a more hopeful vision of what the city and community could be. One is the Duwamish leader for whom the city was named: Chief Seattle, an Anglicization of the Duwamish name Si’ahl. Born around 1780, Si’ahl had been a warrior and chief for decades by the time the European American settlers arrived in the region, and had spent time around both French missionaries and Anglo explorers. While he consistently advocated for his people in their encounters with the Europeans, he resisted taking part in armed conflicts, keeping his tribe out of the Battle of Seattle and negotiating the 1855 Point Elliott Treaty with the white community. He was also known for his skills as orator — while the exact words and details of the 1854 speech for which he is best remain somewhat ambiguous due to their belated transcription, that text’s impassioned cultural and environmental messages ring true to Si’ahl’s lifelong goals.

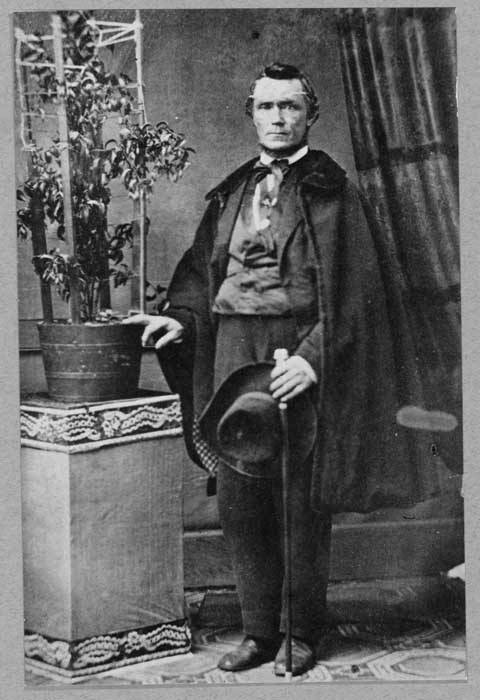

Another inspiring historical figure was a friend of Si’ahl’s and the man who convinced the community to change its name to Seattle: David Swinson “Doc” Maynard. Born in Vermont in 1808, Maynard and his young family moved to Cleveland in 1832; over the next two decades he became one of that city’s most prominent doctors and businessmen. Around 1850, with his marriage ending and the Gold Rush beckoning, Maynard moved West and eventually joined the Denny party that settled Duwamps. Although he did so in pursuit of his own fortune, and claimed a substantial area of land for himself, he was known as an excellent diplomatic and political voice for the community as a whole, even passing the bar in 1856 to become a local lawyer. He was also a consistent friend to and advocate for the area’s Native American communities, and in particular worked closely with both Si’ahl (with whom he drafted the 1855 Treaty) and the powerful Snohomish Chief Patkanim. Maynard’s push to rename the city Seattle was both a diplomatic concession and a reflection of his goal of creating a community in the region that could benefit all those who lived in it.

A third figure amplified the longstanding Asian American presence in the community, despite the 1886 riot and expulsion. Between 1900 and 1910, the groundbreaking Chinese American journalist and author Edith Maude Eaton/Sui Sin Far made Seattle’s Chinatown her town. During this formative and prolific time, Eaton reported on railroad labor and other elements of the Chinese American experience in the Pacific Northwest and also published her own thoughtful and moving autobiographical essay “Leaves from the Mental Portfolio of an Eurasian” (1909) during this time.

As baseball celebrates its stars in Seattle this week, it gives us a chance to commemorate some of these historical bright lights as well.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Very historical and educational