As we celebrate Labor Day 2023, the battle for American workers and their rights is at a particularly fevered pitch. From Starbucks and Dunkin’ to Hollywood and hospitals, newly organized and existing workers’ organizations alike are seeking to unionize and to strike, with the number of work stoppages having risen by 50 percent in 2022 and on pace to surpass that statistic this year. These widespread labor actions are being met with aggressive and even violent pushback from employers and corporations, as well as PR campaigns to demonize the workers. And in education, teachers and librarians are being targeted and fired for a variety of perceived violations, and institutions of public higher education like West Virginia University are eliminating entire departments and their tenured faculty members.

Labor Day itself dates back to the first truly national labor organizations, and that radical history is important to commemorate on the holiday. But the battle to establish labor unions that would fight for workers’ rights goes back further still in America. Those multi-century efforts culminated in both a crucial mid-19th century court victory and a series of subsequent, groundbreaking teachers’ unions.

But before those 19th century achievements, American workers consistently fought for and were denied the legal right to unionize and strike. In 1636, a group of fishermen on Maine’s Richmond Island “fell into mutiny” to protest their wages being withheld; the island’s overseer John Winter fired them all and advised his employer to make such firings official in future contracts. In 1677 New York City, a dozen carmen — operators of horse and cart transportation in the city — went on strike and were criminally prosecuted and fined. The same fate met a group of Savannah, Georgia, carpenters who went on strike in 1746 and were informed that an act of Parliament had made such labor actions illegal. While each of these events featured distinct factors, the common thread was that workers faced both employment and legal consequences if they sought to organize.

In the Early Republic United States, with the Constitution and state governments alike offering Americans new legal rights and protections, a number of worker communities took their efforts to organize to the courts. The initial, frustrating precedent for such decisions came in 1806’s Commonwealth v. Pullis, a Philadelphia ruling in response to a shoemakers’ strike that defined organizing workers as “transitory, irresponsible, and dangerous” and their “combination” as illegal. While subsequent decisions over the next few decades largely followed that 1806 precedent, they did allow for circumstances in which labor actions could be legal and legitimate. In both 1821’s Commonwealth v. Carlisle (also involving Philadelphia garment workers) and an 1823 trial of striking New York hatters, the courts ruled that the workers had in those specific instances organized in unlawful ways, establishing the possibility that an alternative, lawful “combination” could occur and produce legitimate labor actions. As economic historian Edwin Witte has put it, “The doctrine that a combination to raise wages is illegal was allowed to die by common consent.”

That common consent received crucial judicial support in Commonwealth v. Hunt (1842), a Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court decision that broke from the Pullis precedent to fully establish labor organizing as legal. In the late 1830s, members of the Boston Journeymen’s Bootmakers’ Society organized a series of strikes to protest low wages; when they were fired, they took their case to the courts, where they were initially met with the same guilty verdicts as had so many past American workers. But this time their lawyer, the politician and reformer Robert Rantoul Jr., appealed the case to the Supreme Judicial Court, and there Chief Justice Lemuel Shaw rendered his groundbreaking decision. Workers, he argued, are “free to work for whom the please, or not to work, if they so prefer…. We cannot perceive that it is criminal for men to agree together to exercise their own acknowledged rights, in such a manner as best to subserve their own interests…The legality of such association,” he added, “will therefore depend upon the means to be used for its accomplishment. If it is to be carried into effect by fair or honorable and lawful means, it is, to say the least, innocent.”

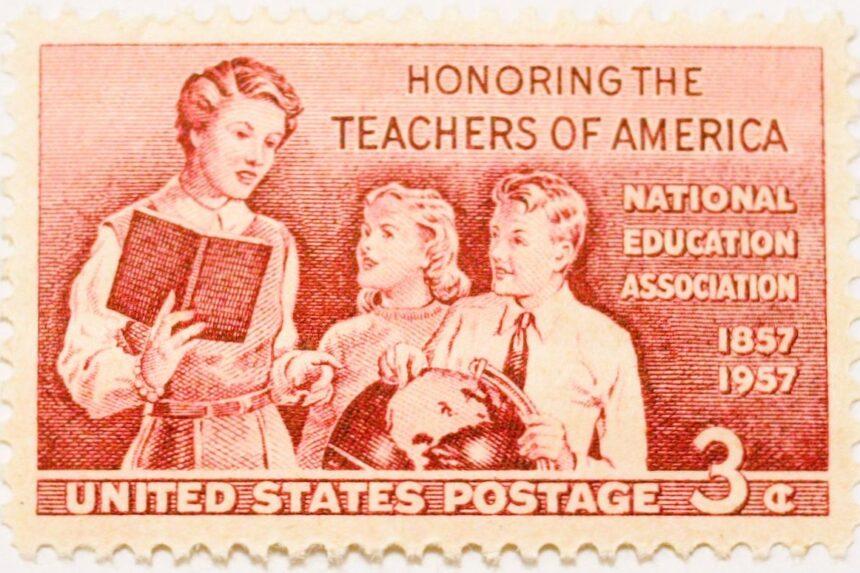

The Hunt decision offered significant support for communities of workers seeking to organize, and the next two decades saw the creation of a number of such early labor unions. Many of those early unionizing efforts took place in the new and evolving world of American public education. Perhaps the first of those groundbreaking educational unions was the Michigan State Teachers Association (MSTA), which was organized in 1852; two years later, in December 1854, 175 teachers met in Indianapolis to form the Indiana State Teachers Association (ISTA). Those two organizations spurred the creation of many more around the country, and in 1857 ten teachers’ associations issued a joint call for American teachers to “unite to advance the dignity, respectability, and usefulness of their calling.” In response, 100 educators met in Philadelphia and formed the National Teachers Association (NTA), with a mission to “elevate the character and advance the interest of the profession of teaching, and to promote the cause of popular education in the United States.”

The two parts of that sentence are importantly interconnected, and reflect the multi-layered realities of these battles for labor unions and rights. These workers and organizations do not only seek to advance their own interests, although of course that is a primary and natural goal of labor activism. They also and through the same actions seek to improve the collective good — in their specific professions and industries, but likewise for all who utilize and benefit from their work. These centuries of labor actions, and these 19th century turning points that they produced, paved the way for the truly nationwide labor movement from which all Americans have benefitted, and that we commemorate and celebrate on this holiday.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

There’s a lot to unpack here, and I appreciate the links. It took me a couple of days (as I had time) to read it thoroughly. I really like the 1857-1957 Centennial stamp showing what an honorable profession teaching was, and the high regard teachers were held in, justifiably so. Many teachers today still deserve to be seen in this light, but many do not, unfortunately. It’s hard for me to picture a comparable bicentennial stamp decades from now.