This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

It’s hard to describe our current moment as a golden age for much of anything in America, but we are indeed amidst a renaissance of protest art. Portland’s inflatable resistance frogs have morphed into a consistent presence of life-size artistic costumes at protests, including at the massive #NoKings rallies on October 18th.

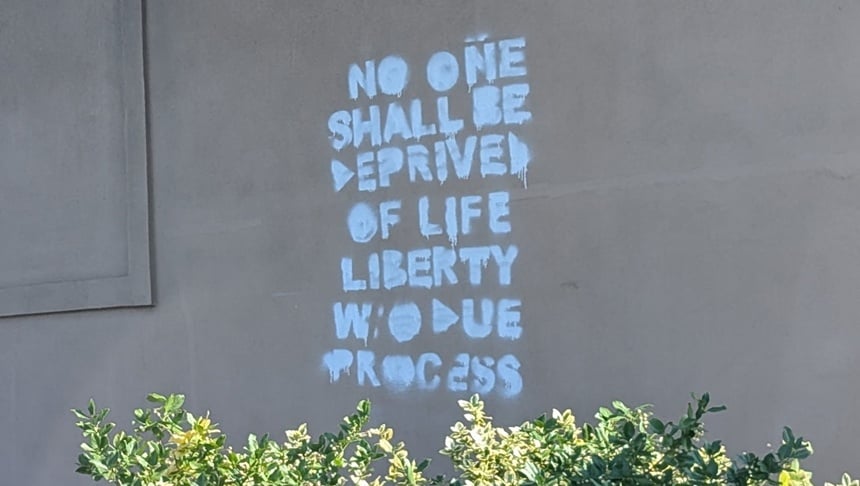

And public and street art has likewise become a consistent space for expressions of protest and resistance, as illustrated by this graffiti quotation from the 14th Amendment found on the wall of an abandoned Dunkin Donuts near my university in Fitchburg, Massachusetts.

Those examples comprise two distinct but interconnected categories: protest art — artworks present at or directly representing collective actions; and art as protest — artworks that themselves comprise an expression and form of resistance. Both types are part of a long, rich history, as art has been integral to the foundational American story of protest. Here I’ll highlight just a few examples of each category from across our history.

Protest Art

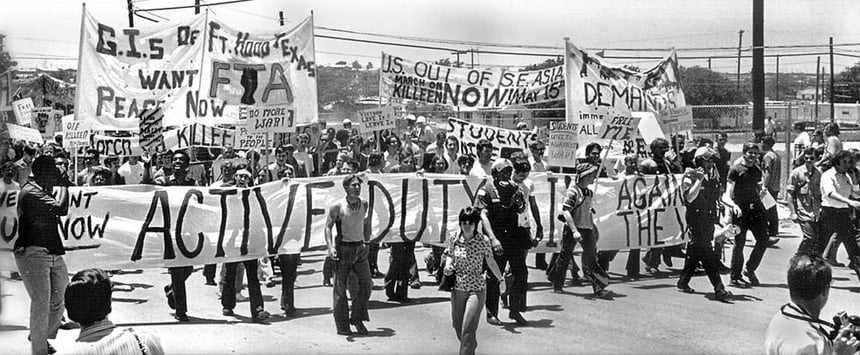

By far the most ubiquitous forms of protest art across our history have been the signs, posters, and banners that protesters carry and display. The Silent Sentinel women’s suffrage protesters in 1910s Washington conveyed their whole perspective through their famous placards. Striking coal miners in 1920s West Virginia both challenged the authorities and planned their collective actions through their use of signs. 1960s marches for civil rights and against the Vietnam War became synonymous with the slogans expressed on their posters. And these trends have continued into the 21st century, as reflected by the central role of signs and banners in protest movements such as 2011’s Occupy Wall Street encampment and the 2020 #BlackLivesMatter marches.

The art displayed at protests has also been consistently complemented by artistic representations of those protests, works that have helped connect audiences who could not be present to the stories of these collective actions. One of the most stunning examples is artist Richard Hamilton’s 1970 screenprint Kent State, which turned a television image of that anti-war protest’s violent and tragic end into an expression of mourning and righteous anger. Another striking work from that same era is Andy Warhol’s 1964 screenprint Birmingham Race Riot, which was based on a Life magazine photograph and captures the precise moment when police dogs were let loose on African American civil rights protesters in that Alabama city.

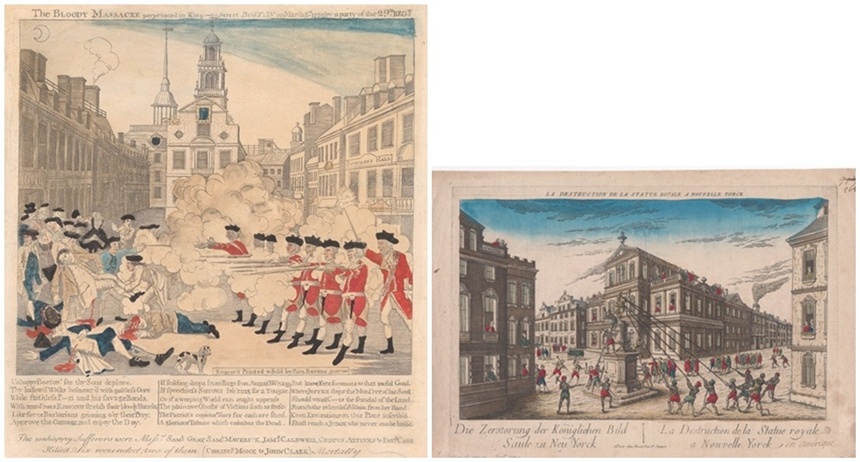

Before the age of mass media, such artistic renderings of protests were even more vital in publicizing those collective actions. No contemporary image of the American Revolution was more famous nor more influential than Paul Revere’s 1770 engraving The Bloody Massacre, which the Boston silversmith and activist based on artist Henry Pelham’s earlier engraving and which helped shape the public understanding of and outrage over that tragic event. Equally prominent and influential across the pond was the anonymous 1776 French engraving The Destruction of the Royal Statue at New York on July 9, 1776, which not only depicts this important moment in the American Revolution, but which also features enslaved and free Black men as the predominant participants.

Art as Protest

Artists and their artworks have also served as their own form of protest across our history. One of the most striking protest artworks is Man at the Crossroads (1933), a fresco painted by the Mexican American painter and muralist Diego Rivera. Installed in the lobby of New York City’s Rockefeller Center during the depths of the Great Depression, Rivera’s fresco features a central portrayal of a laborer amidst a number of other contrasting images of capitalism and communism. The work was so controversial that Nelson Rockefeller ordered it plastered over, a destructive act that only amplified the work’s status as protest.

Less than a decade later, in the early 1940s, the African American artist Jacob Lawrence created another epic artwork, his Migration Series. Among the sixty vibrant panels in that series depicting stories of the Great Migration was There were lynchings. (1940-41), one of the most bracing and powerful American protest artworks. With the lynching epidemic very much ongoing, and with the continued absence of any substantive federal response to this century-long history of racial terrorism, Lawrence depicts in a simple human form the true effects of such violence on both individuals and an entire nation.

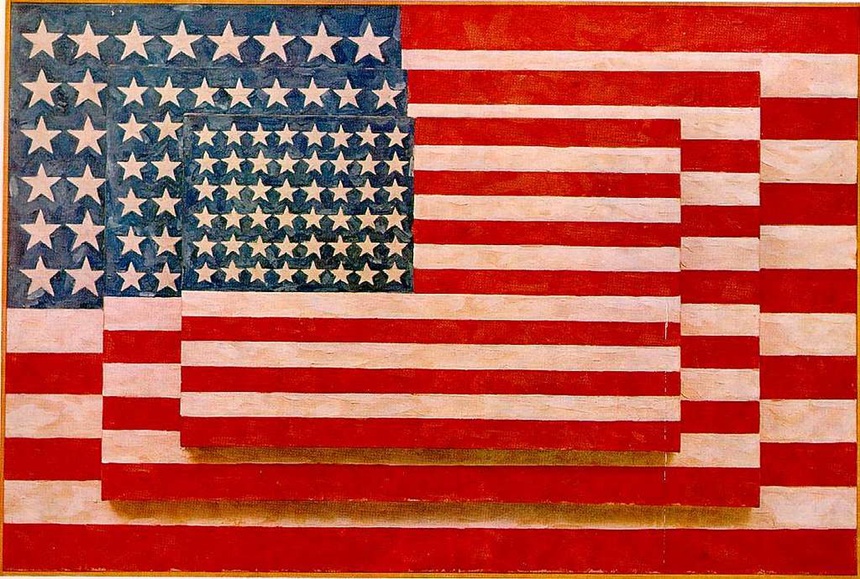

In 1954-55, with the McCarthy era of the early Cold War ongoing and the civil rights movement in its foundational stages, the painter and printmaker Jasper Johns turned his attention to a new artistic endeavor: Flag, the first painting in his flags series. Over the next half-century Johns would create 27 paintings, 10 sculptures, 50 drawings, and numerous other works depicting the American flag, each unique and featuring Johns’s own artistic choices alongside the flag’s details. Johns’s flags are not as direct a form of artistic protest as Rivera’s and Lawrence’s works, but they nonetheless ask their audience to look and think closely at a seemingly familiar American image and icon, a powerful way that art can challenge our existing perspectives.

Artistic protests can also push us out of our comfort zones in more dramatic ways. No American artist achieved that goal better than Keith Haring, the artist and activist who emerged from New York City’s graffiti subculture to produce iconic 1980s paintings and murals depicting the AIDS epidemic (from which Haring himself died in 1990). Haring chose to create many of his works in public, in direct relationship to and confrontation with audiences. As he later put it, “The subway drawings were, as much as they were drawings, performances. It was where I learned how to draw in public. You draw in front of people. For me it was a whole sort of philosophical and sociological experiment. When I drew, I drew in the daytime which meant there were always people watching. There were always confrontations, whether it was with people that were interested in looking at it, or people that wanted to tell you you shouldn’t be drawing there.”

But if the history of protest art and art as protest tells us anything, it’s that art can be created anywhere and belongs everywhere.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I don’t generally dignify Midnight’s comments with responses, but this one is worth sharing:

I grew up in Central Virginia, and have at least driven through (and spent time in in many cases) most of the small towns and rural communities around there. Pretty much all of them have murals and other forms of art as protest, expressing perspectives that might well horrify Midnight but are essentially and beautifully American. Protest, like art, happens everywhere in America, as it well should as it’s as defining as any part of us.

Ben

Protest art does nothing more than just invoke further divisiveness between the citizens of our country. Albeit, a form of “free speech” and I oppose any type of censorship of actual facts, but not feelings. Tell you what….Try that kind of protest art in a small rural town or community. See how far it goes and where it takes you. Go ahead. Give it a shot. Folks, that kind of $h*t only happens in cities and urban areas where people don’t have anything else better to do and live inside their own little world.

US Dollar 2,000 in a Single Online Day Due to its position, the United States va02 offers a plethora of opportunities for those seeking employment. With so many options accessible, it might be difficult to know where to start. You may choose the ideal online housekeeping strategy with the bc-40 help of this post…

See more➤➤➤➤➤➤➤ the site is mention in my name for more info