This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

Impossible as it might be to believe, the math doesn’t lie, and the math tell us that with the end of 2025 we have completed one quarter of the 21st century. We’ve faced more than our share of historic events across the past 25 years, and while each has felt unprecedented, they all nonetheless echo and extend prior American histories. So for a special quarter-century Considering History column, I offer contexts for ten of the most significant political, social, and cultural events and trends of the last two and a half decades.

The Supreme Court’s Decision in Bush v. Gore (2000)

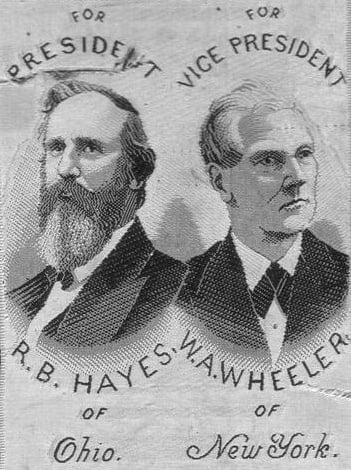

The Supreme Court had never before directly intervened in a U.S. presidential election, and their hugely controversial decision set the stage for the Court’s increasingly (if not newly) political role in the 21st century. But our two prior most contested presidential elections offer important, contrasting contexts for 2000: the election of 1800, which came down to a vote in the House of Representatives to elect Thomas Jefferson over Aaron Burr, but which was followed by a peaceful transition that reinforced the fledgling nation’s commitment to democracy; and the election of 1876, which was so close that it required the creation of a new Electoral Commission that then handed all 20 contested electors to Rutherford B. Hayes in a process so clearly politicized and potentially corrupted that it remains infamous to this day.

9/11 and the Afghanistan and Iraq Wars

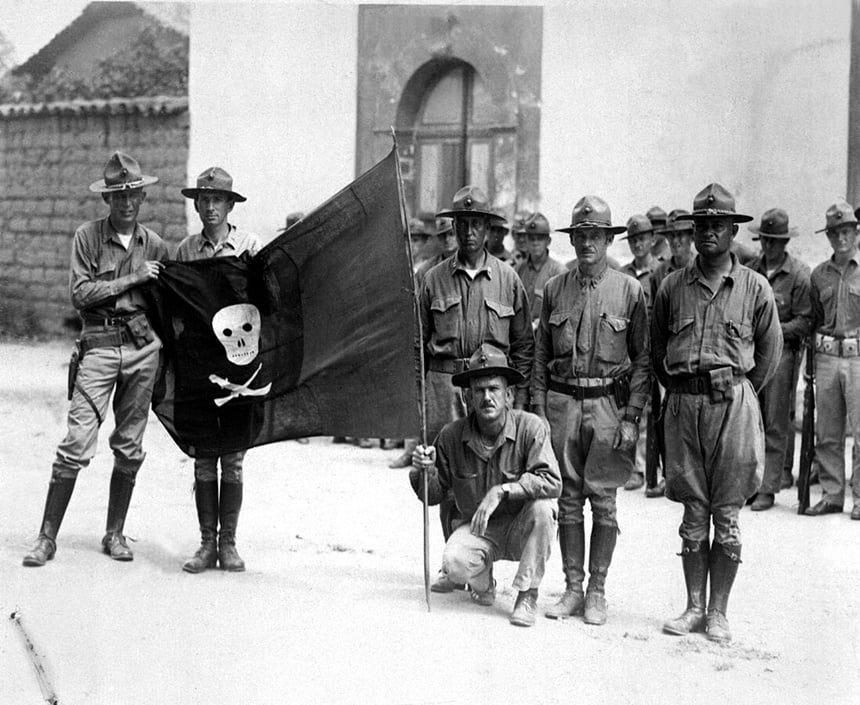

The most destructive terrorist attack on U.S. soil produced countless changes in the decades that followed, but none more significant than the “War on Terror” narrative that led to two of the longest military conflicts in our history. Perhaps the most relevant historical parallel for those effects is the early 20th century U.S. occupation of and guerrilla war in the Philippines, an occupation that began with a different conflict (the Spanish-American War) but that morphed into a brutal multi-decade quagmire. But that’s just one of the many foreign occupations that the U.S. undertook in the first decades of the 20th century, including two distinct occupations of Nicaragua alone and another of Haiti that lasted nearly two decades, each of which reshaped these nations while dividing the American people over their legality, constitutionality, and morality.

Hurricane Katrina

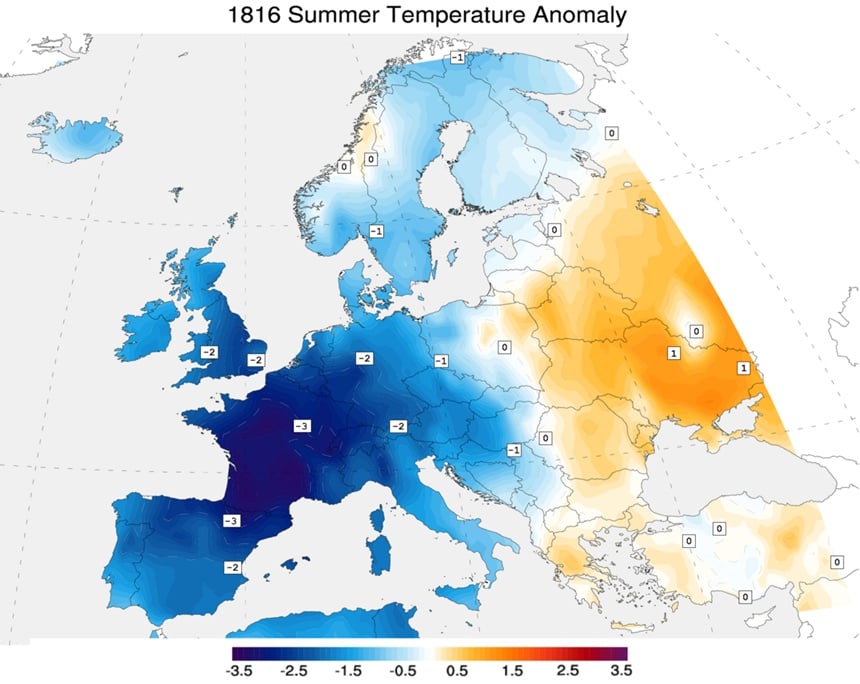

I wrote multiple recent columns, here and elsewhere, for the 20th anniversary of one of the worst natural disasters (and man-made aftermath) to ever hit the U.S. Other similarly historic and destructive disasters can help contextualize Katrina, including the Great Galveston hurricane of 1900, known as the “deadliest natural disaster in United States history”; and the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, which was not only our most destructive river flood but which also in its aftermath reflected the realities of racial segregation and prejudice. But if we take a step back and look at Katrina among the worsening environmental disasters that have accompanied the climate crisis, another historical event offers an even more relevant summer: 1816’s “Year without a Summer,” a profound climate crisis that affected the entire world, produced widespread economic, political, and social changes, and presents models for how societies can respond to such environmental effects.

The Great Recession of 2008

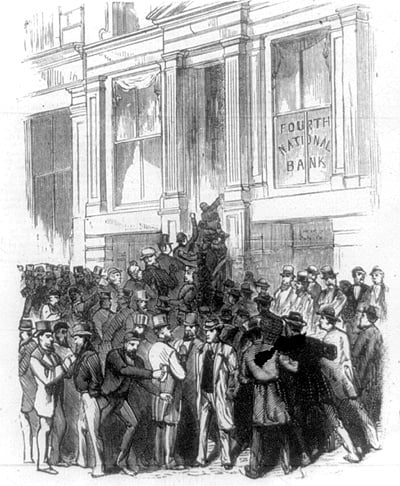

The late-2007 mortgage and housing crashes produced America’s deepest economic crisis since the Great Depression, and that 21st century Great Recession has thus often been compared to America in the 1930s. But there are also striking and illuminating parallels to two 19th century economic crises: the Panic of 1837, which resulted from both rampant land speculation (similar to the 21st century mortgage crisis) and predatory banking facilitated by President Andrew Jackson’s opposition to federal banking oversight (like the pre-2008 period of federal deregulation); and the Panic of 1873, which greatly amplified the wealth disparities that led to the Gilded Age (highly relevant as our Second Gilded Age deepens) and that contributed to the rising anti-immigrant sentiments that led to the Chinese Exclusion Act and a period of profound xenophobia and exclusion.

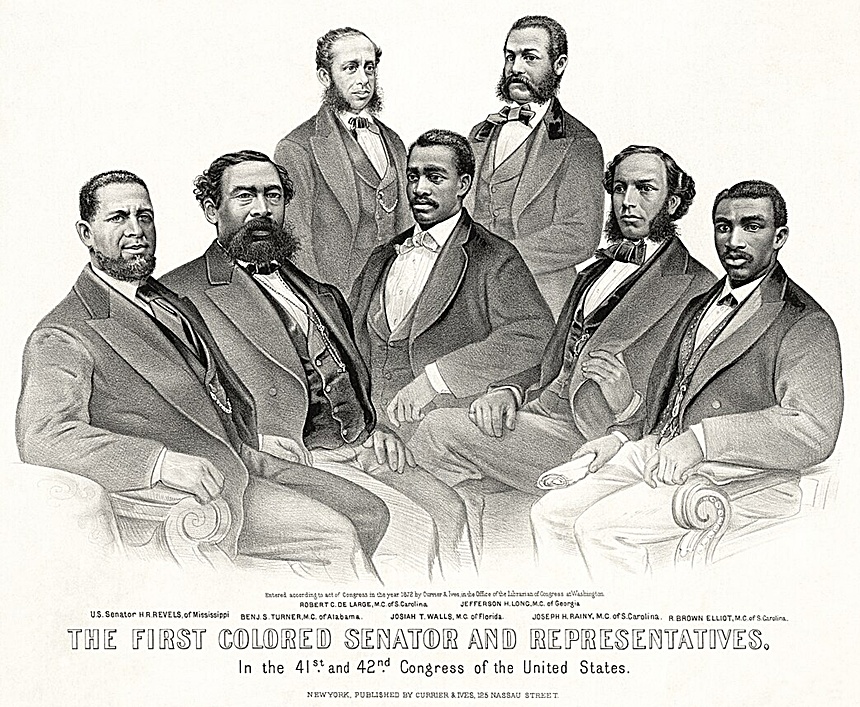

President Obama

The President elected amidst that 2008 economic crisis offered a potent vision of hope and change, not only for those current realities but also as the first Black President; sadly his administration produced a period of intense reactionary and white supremacist backlash that included a widespread conspiracy theory that he was not even an American. While both Obama’s presidency and the backlash were certainly unprecedented in many ways, there was a similar two-part historic moment: the post-Civil War Reconstruction era, which has become known as the Second Founding due to the genuinely revolutionary models for a more inclusive and just nation offered by (for example) the three Constitutional Amendments passed during those years; and the presidency of Andrew Johnson, who embodied and amplified the white supremacist backlash to Reconstruction and whose reactionary policies paved the way for the neo-Confederate forces that would dominate American politics and society for many years to come.

Marriage Equality

After years of debates and state laws and court cases, in 2015 the Supreme Court ruled, in the landmark Obergefell v. Hodges decision, that the fundamental right to marry was guaranteed to same-sex couples by the 14th Amendment. That right remains enshrined in federal law, but recent years have seen significant erosions of other civil rights for LGBTQ+ Americans, and particularly for transgender folks. Two under-remembered 20th century events offer contexts for both advances and the continued challenges that follow them: the establishment of the groundbreaking Society for Human Rights, which when created in 1924 by German immigrant and U.S. World War I veteran Henry Gerber, became the nation’s first gay rights organization; and Executive Order 10450, signed by President Eisenhower in April 1953, which banned gay and lesbian federal employees, encouraged both private contractors and U.S. allies abroad to fire their own gay and lesbian employees, and led directly to the Lavender Scare, the McCarthy era purge of federal employees based solely on rumors, allegations, or accusations about their sexuality.

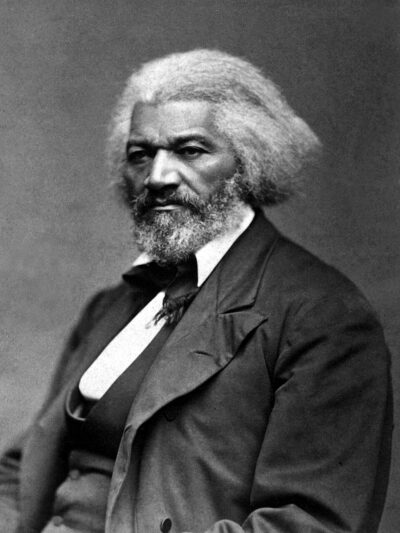

#BlackLivesMatter

In the same years that marriage equality became the law of the land, America also saw the creation and spread of the #BlackLivesMatter movement, the largest collective push for civil rights since at least the heyday of the 1960s (if not in all of our history), and one that as a hashtag activist movement utilized new technologies such as social media and smartphones. The movement’s focus on organizing massive marches to both bring people together and spread the message to audiences around the world echoes the longstanding March on Washington movement, a civil rights activist effort that began as early as A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin’s groundbreaking 1941 march designed to challenge racial segregation in the workforce during World War II. And its reliance on new technologies and media parallels the vital role that newspapers and other periodicals played for the early 19th century abolitionist movement, with publications like William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator and Frederick Douglass’s The North Star both sharing arguments with audiences far and wide and offering a space where activists could connect to one another and build the collective movement.

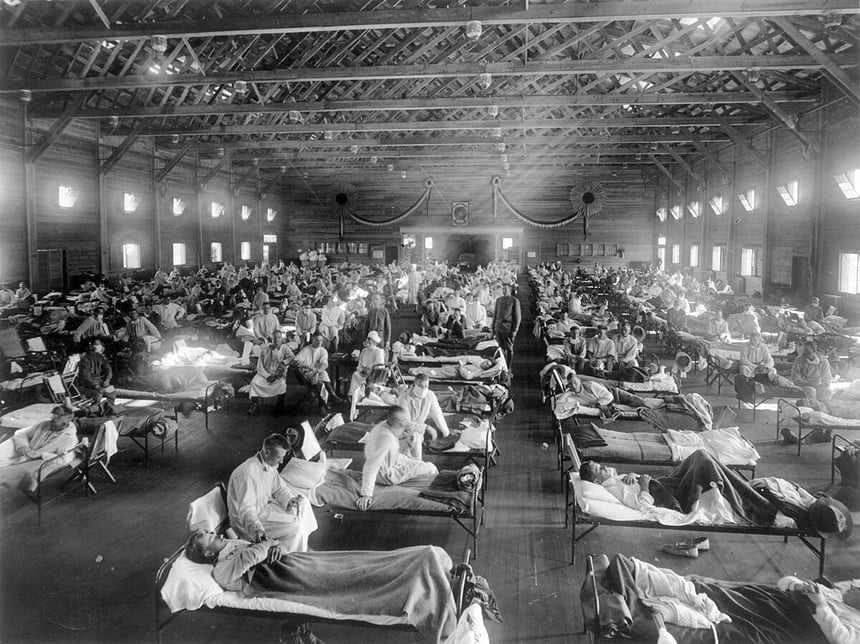

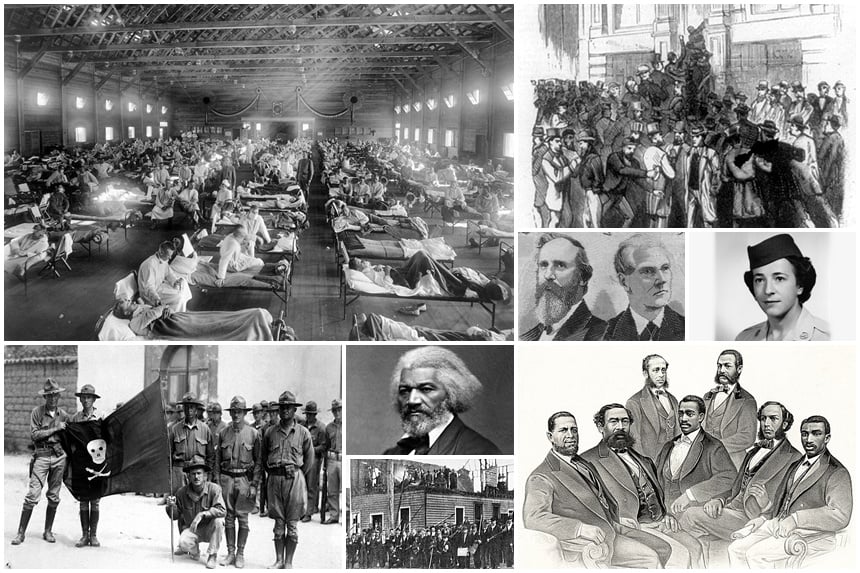

Covid

The clearest historical parallel to the global COVID-19 pandemic suggests that it is far from a given that we will remember it as fully as we should. The influenza pandemic of 1918-20 likewise affected every corner of the globe, and was hugely devastating in the United States, where it afflicted 25 percent of the total population and where 675,000 people lost their lives (more than the combined casualties of World War I, World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War). And yet the pandemic would be almost entirely absent from 1920s cultural works, particularly when contrasted with World War I, which affected far fewer Americans but would play a central role in such iconic 1920s works by T.S. Eliot, Ernest Hemingway, and F. Scott Fitzgerald. It’s easy to understand the collective psychological need to memory-hole such a horrific period, but that doesn’t make such amnesia any less dangerous.

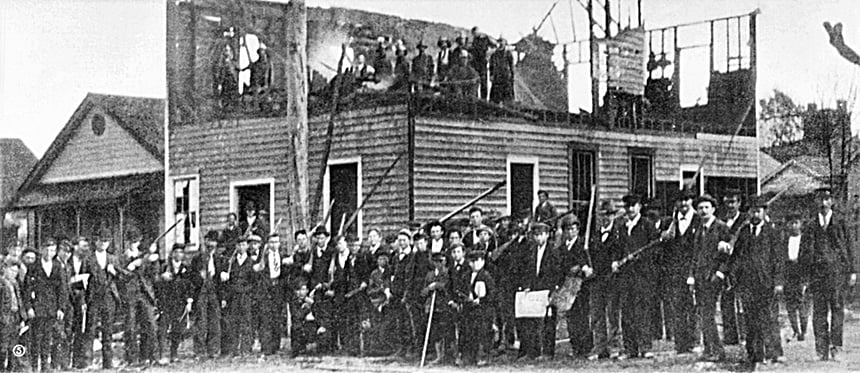

January 6th

Almost exactly five years ago, thousands of people attacked the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C., hoping to stop the certification of the 2020 presidential election. Much of the reporting and analysis of the event called it the first break from our foundational tradition of a peaceful transfer of power. However, the events of January 6th parallel what happened in Wilmington, North Carolina in November 1898: an overt coup d’etat, with the city’s democratically elected government replaced by force by an armed mob; and a seemingly spontaneous “riot” that was in fact carefully planned and led by both local political leaders and organized militias who had come to the city from far and wide. And as extreme as Wilmington was, it was likewise not singular, and instead simply a particularly telling example of the longstanding intersection of white supremacist violence and election interference.

Social Media and A.I.

Most of the 21st century events I’ve highlighted in this list took place, or at least were initially created, in a particular moment. But the most influential trends of the 21st century were those associated with the interconnected pair of new technologies that have come to dominate society over the last 25 years: the internet and smartphones. Those two technologies have combined to produce social media, the most widespread form of community for most contemporary Americans; and are instrumental in the rise of generative A.I., the most striking and divisive invention of the last few years. While these technologies are genuinely new to the 21st century, they can still be contextualized with prior developments like the rise of motion pictures almost exactly a century ago. It reminds us both of the terrifying power of such technologies to be used for propagandistic purposes, as we can see with the central role the first blockbuster film The Birth of a Nation (1915) played in the creation of the Second Ku Klux Klan; and of the ways that inspiring voices can resist and challenge those trends, as with the work of groundbreaking Black filmmaker Oscar Micheaux, whose 1920 film Within Our Gates offered a direct and potent response to Birth of a Nation’s racism.

Wherever the next quarter-century takes us, two things are certain: There will be historical precedents and parallels for these current events; and remembering and engaging with them will remain vital goals if we are to navigate them as successfully as possible.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Feel free to point out where my facts are either absent or inaccurate, John. I’m quite serious, I take the goals of evidence and accuracy incredibly seriously, in every column I write, and you’re welcome to comb through every one across my 8 years writing for the Post and let me know whenever I’ve come up short, and I’ll gladly own them.

Ben

Certainly sounds like a left wing oriented article. How about facts without the interpreted edited version of these events?

A turning point in history was when the FCC was no longer allowed to regulate for TRUTH. It seems that the FCC is still operational in the main-stream media, but the cable networks are allowed to say anything and “fact checkers” are ignored or called FAKE. Indeed, AI is collecting a huge pile of false news now that has to be sifted through in order to find any truth. The pile just keeps growing and we just keep absorbing all of this nonsense. We are more susceptible to scams and lies than ever before because no one TRUSTS any sources of news anymore. Perhaps we might learn the value of fact checking and the FCC must be run by a non-partisan group of independent fact checkers who can show the primary sources where all of this information is coming from.

A couple of authorial follow-ups to the comments, both present and now (appropriately) absent:

–I appreciate that response, Sheri. I had Trump in my original list, but the Post tries (understandably) to stay away from the topic as much as possible, ridiculously divisive & ugly as things tend to get (see those now-deleted comments). Suffice to say, if you want historical contexts for Trump, you can look at literally everything that’s been the worst in our histories. Full stop.

–I’m glad that the now-deleted comments are deleted. But also, man oh man do they reveal how much we need historical contexts, critical thinking, analysis of all kinds.

Ben

Oh, yes, Donald Trump has been a force in American life and in American politics for the last 20 years. But it is not a good force in either arena. This wannabe dictator has profoundly changed this once great nation into a bed of hatred where love exists no more, and where kindness has been kicked to the side of the road. Our Founding Fathers are groaning in their graves. But they made some grave mistakes. How charming to think that they thought that the Supreme Court would always rule in accord with what is good and fair and right in America. Did they really think that so many of our congress men and women would be moved,not just to be elected again, but to do the right thing for the people? Those wise men envisioned a country of, by, and for the people. They envisioned a country where an informed electorate would vote for the best candidates. But sadly, we do not have an informed electorate in the United States. More than a third of Americans can not read or write or speak except at a very rudimentary level, and Donald Trump knew this, and he used it to his advantage. And sadly, this great American experiment is nearly at its’ close. The future looks grim.

Huh. The January 6 attack was a “sham,” even though we all saw it unfold before our eyes, by people wearing MAGA hats. BLM is also a “sham,” but I’m not sure what you are getting at, unless you think that we have solved our racial issues, which, okay. Either way, I don’t think you know what “sham” means. And then there’s that nonsense about “rampant” “illegal votes” which are supposedly supported by “more and more evidence,” none of which actually exists, but whatever.

But you are right about 9/11 being a profoundly important event in the last 25 years, probably outranking either Bush v. Gore or Katrina. And, yes, the election of President Trump is also profoundly important, as it will likely mark the moment when America ceased to be the shining city on a hill extolled by Ronald Reagan. A pity, but that’s what America wants, I guess.

There are a few minor issues to quibble about regarding the choice of events on this list that shaped history in the first 25 years of the 21st century. But they are eclipsed by the elephant in the room. Love him or hate him, President Donald Trump has been a force in American politics and world events that has forced a change in both dominant political parties. Since when is our approach to understanding “history” merely an expression of what is popular, approved of, or accepted by an author? Our political silos do affect our thoughts and words, but this list could have been more robust and therefore more engaging.