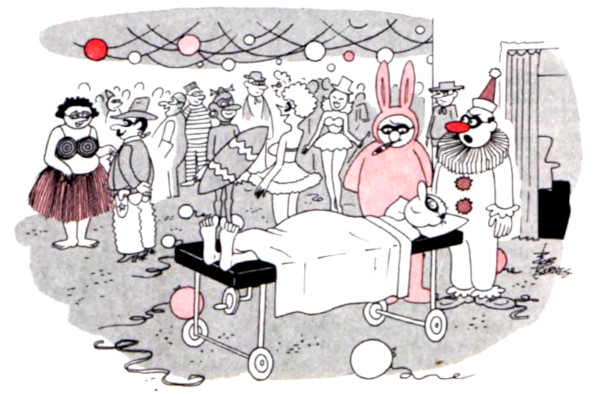

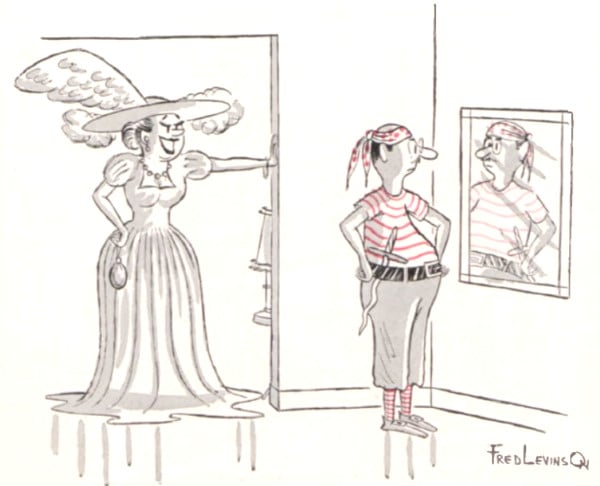

Cartoons: Halloween Is for Grownups, Too

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Costume parties must have been popular in the 1950s, because these cartoons aren’t just from our October issues. But we’re posting them in this collection to remind you that adults can have fun at Halloween, too!

O’Brien

October 29, 1955

Walt Wetterberg

November 12, 1955

Les Colin

April 7, 1951

February 11, 1956

Busino

February 12, 1966

Bob Barnes

January 1, 1955

Fred Levinson

June 4, 1955

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Curtis Stone’s Oven-Roasted Baby Beets with Orange Vinaigrette

The earthiness of beets provides a nice counterbalance or alternative to a traditional, sweet cranberry sauce, and the vinaigrette with orange brightens up the dish. The beets can be roasted and the vinaigrette prepared ahead so that you can pull together all the components once you pull your turkey out of the oven.

Oven Roasted Baby Beets with Orange Vinaigrette

(Makes 4 servings)

- 2 bunches baby red beets, scrubbed, stems trimmed

- 2 fresh thyme sprigs

- 2 garlic cloves, finely chopped

- 1 shallot, cut in half

- 1 tablespoon extra-virgin olive oil

- 1 tablespoon water

- 2 cups (not packed) baby arugula

Vinaigrette:

- 2 oranges

- 1 tablespoon balsamic vinegar

- 1 tablespoon finely chopped shallot

- 1 teaspoon Dijon mustard

- 2 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

Instructions

To roast beets: Preheat the oven to 400°F. Place beets, thyme, garlic, and shallot in center of large piece of aluminum foil, then fold up sides of foil to form pouch, leaving open at top. Pour oil and water over the beets and season with salt and pepper. Roast beets for 25 to 30 minutes, or until small paring knife can be inserted into center of a beet with no resistance. Set aside to cool slightly.

To make vinaigrette: Into medium bowl, finely grate orange zest from 1 orange. Cut off tops and bottoms of 2 oranges. Using small sharp knife, cut away peel and white pith from oranges, following curve of oranges from top to bottom. Holding 1 orange in your hand and working over bowl, make 2 cuts along membranes on either side of segment, then lift segment out of membranes and drop it into bowl. Repeat to remove all segments from both oranges, and set segments aside. Squeeze membranes over bowl of orange zest to release 1 tablespoon of juice.

Whisk vinegar, shallot, and Dijon into bowl of orange zest and juice. Slowly add oil while whisking to blend completely. Season vinaigrette to taste with salt and pepper.

To serve: Quarter beets and arrange them on center of platter with orange segments. Sprinkle arugula over. Drizzle vinaigrette over and serve.

Make-Ahead: The beets can be roasted and vinaigrette and orange segments prepared up to 8 hours ahead, covered separately and refrigerated. Let beets and vinaigrette stand at room temperature for 20 minutes and rewhisk vinaigrette before serving.

Per serving

- Calories: 196

- Total Fat: 10 g

- Saturated Fat: 1 g

- Sodium: 79 mg

- Carbohydrate: 22 g

- Fiber: 5 g

- Protein: 2 g

- Diabetic Exchanges: 0.5 fruit, 2.5 vegetable, 2 fat

Credit: Recipe © Curtis Stone; photo by Ray Kachatorian

Horror for the Whole Family: Halloween Books for All Ages

Halloween is upon us once again. Last year, the Post looked at the question, “What’s the right horror film for the whole family?” And while staying in for movies is still an excellent choice for this spooky season, especially with the pandemic still present, films aren’t your only choice for eerie entertainment. So the new question becomes, “What are the right horror reads for the whole family?”

Every family’s view of content is different, and every family has a different standard for when it’s okay for the kids to indulge in scary fare. What we have here are some baseline recommendations, standout books that you might check out as starters, along with some appropriate ages. Again, your own idea of what’s appropriate and when may vary, but that’s why comment sections were created.

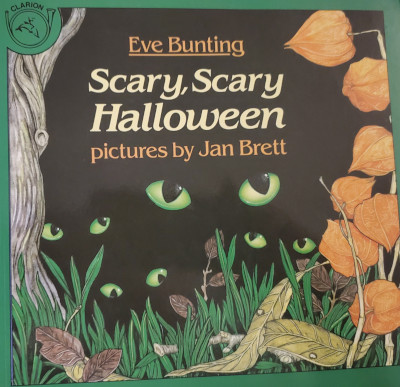

1.The Littles (9 and under): Scary, Scary Halloween by Eve Bunting and Jan Brett (1988)

Halloween-themed picture books abound, with lots of great, funny reads like Goblin Walk, but this one is a superlative effort from two huge talents. Eve Bunting has more than 250 books to her credit; she moves as easily from fiction to non-fiction as she does from picture books to novels. Jan Brett has been writing and drawing books for kids since the 1970s, and she’s received effusive praise for her lovely, intricate art. Scary, Scary Halloween brings them together in a delightful way, with rhyming verse and outstanding visual renditions of a scary Halloween night. An unseen narrator talks of monsters stalking through the neighborhood before the story takes not one, but two, surprise twists. It’s a great one to read to the little ones, and to have them read back to you as they get bigger.

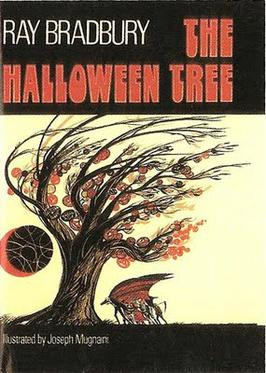

2. Kids to Tweens: The Halloween Tree by Ray Bradbury (1972)

Let’s be clear: Ray Bradbury’s The Halloween Tree is for EVERYONE, but it serves this particular demographic extremely well. Bradbury is, of course, one of the most exalted names in science fiction and fantasy, but he might also be the King of Halloween. His loving and nuanced takes on the holiday cause his name to appear repeatedly (and deservedly) on this list. The Halloween Tree is a touching story about friendship that also delves into the history of the holiday and its antecedent, Samhain. After a boy named Pipkin disappears, eight of his friends come together with the strange Mr. Moundshroud to travel through time to find their friend; along the way, they learn about the traditions of the Greeks, Romans, and Celts, visit medieval France, and witness what happens at Mexico’s Day of the Dead celebration. When the cost of saving Pipkin becomes clear, his friends come together for their friend in a moving finale.

3. Teens: Something Wicked This Way Comes by Ray Bradbury (1962)

Today’s teens have access to a steady diet of horror material in both print and film; between libraries and streaming services, there’s not a lot that they haven’t already seen. That’s what makes Something Wicked This Way Comes special, in a way, because they might not have seen it. Bradbury’s 1962 masterpiece is all about the transition from youth to adulthood, while also baking in the regrets of age. When a strange carnival arrives in Green Town, Illinois on October 23, 13-year-old best friends Will Halloway (born one minute before midnight on October 30) and Jim Nightshade (born one minute after on October 31) are drawn into its orbit. At first, only Will and Jim seem aware of the unnatural events unfolding from the Cooger & Dark’s Pandemonium Shadow Show, but they find an unexpected ally in Will’s 54-year-old father. You can smell the autumn air in Bradbury’s rich descriptions of the season. The story, by turns wistful and terrifying, is one of the gold standards of dark fantasy. Teens can easily identify with the protagonists, as one of the primary forces in their own lives is the pull of adulthood.

4. Adults: A Night in the Lonesome October by Roger Zelazney (1993) and October Dreams: A Celebration of Halloween (edited by Richard Chizmar and Robert Morrish, 2000)

A Night in the Lonesome October (not to be confused with Night in the Lonesome October by Richard Laymon, which is great in its own right) is creepy, funny, delightful, and demented. Zelazney was the celebrated writer of the bestselling The Chronicles of Amber series and dozens of other works; he won the Hugo Award six times and the Nebula three. 1993’s ANITLO was one his favorites of his own work; it was also his last novel, as he died in 1995. But what a great final statement it is. After an introduction, the 31 remaining chapters each take place on one day in October leading to Halloween in late 1800s London. The story is told from the point of view of Snuff, the canine companion and magical familiar of one Jack the Ripper. However, Jack is actually trying to save the world in a story that involves (either directly or by clever parody) the Lovecraft mythos, Dracula, Sherlock Holmes, the Wolf Man, the Frankenstein Monster, Rasputin, and more. The book is by turns haunting and hilarious, with Snuff and the other familiars alternately trying to help their masters save or destroy the world. Surprise alliances and betrayals abound, and it’s a real feat of imagination.

On the darker side, the 2000 anthology October Dreams: A Celebration of Halloween is simply one of the best collections about Halloween ever put to print. Collecting short stories along with non-fiction Halloween reminiscences by a murderer’s row of talent, the book includes the likes of Bradbury, Dean Koontz, Poppy Z. Brite, Christopher Golden, Jack Ketchum, Gahan Wilson, Richard Laymon, Dennis Etchison, Ramsey Campbell, Peter Straub, and many more. At over 650 pages, it’s a slab of fiendish goodness.

5. The Adult History Buff: Halloween: The History of America’s Darkest Holiday by David J. Skal (2016)

An October surprise bonus category! Yes, The Halloween Tree digs into the roots of the holiday, but this is a phenomenal book by one of the most authoritative writers on horror. Skal has written essential non-fiction like The Monster Show: A Cultural History of Horror, Hollywood Gothic, and Something in the Blood: The Untold Story of Bram Stoker, the Man Who Wrote Dracula. Here, he turns his keen insights to Halloween itself. Skal’s real talent lies in engaging a topic on both the macro and micro level, juxtaposing how that topic impacts the culture as a whole while also using laser-precise examples to show just how deeply that impact runs. Skal’s examination runs the gamut from the early Celtic days to a present where we (in non-pandemic years) spend about $9 billion celebrating the holiday.

6. Grandparents: Ghost Story by Peter Straub (1979)

This one goes off theme just a tiny bit, but bear with it. Yes, Ghost Story takes place across multiple time periods with one of the most climactic sequences occurring during a blizzard. But it is one of the grand champions of scary storytelling, and the initial protagonists are a group of older gentlemen and one gentleman’s wife. With many mature main characters and Straub’s deep appreciation for the canon and history of American horror (references to Nathaniel Hawthorne and Donald Wandrei abound, and nods are clearly made to George Romero and Straub’s pal Stephen King), Straub crafts a particularly literary story that thrives on human emotion. There is some really dark stuff, but there are also seeds of hope, especially when the older men reach out to two other protagonists (one much younger) to help them navigate the terror that has them under siege.

And there you have it: like the film list, it’s a list to get you started (and to start discussions). Enjoy this very strange season, get lost in the books that you intend to read, and maybe, just maybe, leave a light on.

Featured image: Marsan / Shutterstock

What’s Happening to Halloween?

America has to face a frightening fact this October: we are still in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. Even with states reopening and calls from certain quarters to get back to business as usual, coronavirus cases are on the rise in 27 states as of this writing. With a proper vaccine still a fair distance from the horizon, many are wondering what to do about that most social of holidays, Halloween. The creepy catch is that there’s no single standard or strategy across the nation, so here’s a snapshot of how different communities are handling various events in the hopes that the outcome isn’t too scary.

The Louisville Jack O’Lantern Spectacular: The Post called this the “Best Halloween Event in the Midwest” in 2018. This year, The Jack O’Lantern Spectacular will still boast over 5,000 intricately carved and lighted pumpkins, but the event will be a drive-thru affair. Organizers decided that it was a solid way to hold the event but still maintain social distancing. The Spectacular, which benefits the Louisville Parks Foundation and requires tickets, runs now through November 1.

Haunted Houses: Local haunted house attractions are a mixed bag. Some have opted to close, and some, like Hanna Haunted Acres, which the Post visited in 2019, will remain open. HHA, considered one of the best haunted house events in the country, lists the series of precautions that they’re taking on the front page of their website. Face masks are required, capacity will be limited, and distancing will be maintained. Contact-free temperature checks are required to enter. The staff has upgraded cleaning procedures and made more hand-sanitizing stations available for patrons. The Hanna website also contains more COVID-19 information for guests, including safety reminders and symptom lists (that could guide you to remain home). Haunted attraction site TheScareFactor.com is maintaining a running list of which regular attractions are open or closed in all 50 states, plus Washington D.C. and Puerto Rico. The state with the most closings is California, with 37, though 32 are open and 90 are unconfirmed; the state with the most remaining open is Ohio, with 72, which is offset by 34 closed and 25 presently unknown.

It’s Free to See the Full Moon (Both of Them): 2020 has been legitimately spooky, so spooky in fact that October this year gets two full moons. By a twin quirk of astronomy and the calendar, the first three days of October have a full moon, and it will be full again on Halloween (which is rare; the last full moon on Halloween that was visible in North America was in 1944). It should be an extremely bright moon as well. Granted, you might not be able to build a whole event out of seeing the full moon, but it’s easy (and free) to do while maintaining socially distancing.

Staying Safe the CDC Way: The Centers for Disease Control added a section to the “Your Health” area of their website that’s all about staying safe throughout the holidays. The section comes with a lengthy introduction about precautions to take in the event that you host or attend any kind of holiday gathering. In the Halloween segment, the CDC lists activities and whether they can be considered lower, moderate, or higher risk. Many traditional activities like treat-or-treating, trunk-or-treat events, indoor haunted houses, and indoor parties fall into the higher-risk area.

Likewise, CNN Health also published a list of 31 activity suggestions that people can do safely. These ideas run from the extremely modern (celebrating with Animal Crossing) to the tried-and-true (Scary Movie Night).

State by State, City by City: Every community, city, and state is likely to have their own rules, which you should be able to find online. Cities like Los Angeles will be shutting down larger gatherings and have forbidden big events like carnivals and haunted houses from operating at all. The famous Greenwich Village Halloween Parade in New York has been cancelled, as have big events in Salem, Massachusetts. Here’s a list of some of the more significant cities with cancellations or big changes.

One example of state rules can be found in the Illinois Department of Public Health’s response to Halloween activities. The IDPH encouraged people to stay at home, but also acknowledged that people will go out anyway and therefore issued guidelines. A statement from IDPH Director Dr. Ngozi Ezike in The Chicago Tribune emphasized some familiar points: “Remember, we know what our best tools are: wearing our masks, keeping our distance, limiting event sizes, washing your hands, and looking out for public health and each other.” Illinois is also one of several states that is prohibiting indoor haunted houses at the moment, though outdoor versions may still occur under restrictions. Consult the guidelines for your community to see what is and isn’t allowed this year.

The Choice is Yours: The decision about what to do (if anything) for Halloween is up to each individual (or each family). The best practices are obviously to be cautious and thoughtful. Costume masks don’t work like personal protection masks, for example, and indoor gatherings offer some of the highest risks. There are clearly a number of ways to have a good time, even if we have to modify the expectations set by previous holidays. As long as you practice social distancing, make smart choices, and avoid babysitting in Haddonfield, Illinois, you can still have a Happy Halloween.

Featured image: (From the 2018 Louisville Jack O’ Lantern Spectacular; photo by Becky Brownfield)

9 Things You Didn’t Know about Independence Day

America: the land of the free, rebellious, and stubborn. While their portraits radiate opulence, the Founding Fathers exemplified these other virtues as much as current American citizens do. Check out these nine Independence Day facts that you probably didn’t learn in school:

1. Although Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, the first delegates didn’t start officially signing it until August 2.

2. John Hancock, known for his large signature on the Declaration, is rumored to have said, “King George will be able to read that!” when he signed.

3. John Adams believed that July 2 was the correct date on which to celebrate the birth of American independence, as the Continental Congress agreed to be independent on that day. Adams reportedly turned down invitations to appear at July 4 events in protest.

4. During the first Independence celebrations in 1776, some colonists held mock funerals of King George III to signify the end of the monarchy’s power over the colonies.

5. John Dunlap was the first to print copies of the Declaration of Independence. Extant copies have fetched $8.1 million online. One lucky person found a copy in a $4 frame purchased at a flea market.

6. Each year on Independence Day, the Liberty Bell is tapped 13 times by descendants of the Declaration’s signers to commemorate the patriots from the 13 original colonies.

7. Presidents Thomas Jefferson and John Adams both died on the 50th anniversary of America’s independence: July 4, 1826.

8. King George III didn’t respond to the Declaration of Independence until October 31, 1776, when he called Revolutionary leaders power-hungry and affirmed the British victory against Washington at the Battle of Long Island.

9. After George Washington read the Declaration to a crowd in New York City, colonists tore down a statue of King George III; it was later melted down and turned into over 42,000 musket balls for the rebel army.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Why Americans Still Eat Barbecue on July Fourth

Dearly beloved, we are gathered in this moment to celebrate the culinary union of barbecue (a.k.a. barbeque, bar-b-que, bar-b-q, and BBQ) and Independence Day (a.k.a. July 4 or “the Fourth of July”). This moment is a culmination of the Founding Fathers generation’s need for the right to party.

In the early history of our republic, Independence Day was often the biggest community festival of the year. Barbecue, which developed as a new, fusion cuisine well-suited for festive occasions by the late 1600s and early 1700s, became the ultimate party food during the period when Fourth of July celebrations gained civic and social momentum. The two have been linked up ever since.

Barbecue, of course, was a thing long before the British colonists ever thought about declaring independence from their sovereign. I’m not talking about hamburgers and hot dogs on a kettle grill. I’m talking about “old school” barbecue, where a whole animal carcass was skewered with wooden poles and cooked over a trench filled with burning coals from hardwood trees. Pre-20th century, African Americans typically did the labor-intensive cooking. They used the piercing poles to flip the carcasses periodically and seasoned the meat by basting it with a sauce primarily made of vinegar and red pepper. Today, we tend to fall into stereotypes about which meat authentically represents the barbecue of a region, but back then, anything could go over the pit regardless of geography. Cows, pigs, sheep, and even opossum were the most common.

In the American South, the ideal setting for a barbecue was a rural open space with beautiful trees and a spring nearby. In between plates of food, people would play games, get their drink on, and shoot guns. Barbecues were originally social get-togethers for family and friends, but eventually any life event, like a funeral or a wedding, was an excuse for a barbecue. By the late 1700s, barbecue was already a cooking process (verb), a descriptor for a kind of cooked meat (adjective), and a form of entertainment (noun). All three were very much a part of social life in the American South, especially in Virginia.

Barbecue’s backstory is rooted in the culinary traditions of the Indigenous people who lived in what would later be called “North America” after European contact. Historian Joseph Haynes shows in his well-researched book Virginia Barbecue that British settlers in the Virginia colony melded their meat-cooking techniques with the meat-smoking techniques of the Powhatans who lived in that area. Barbecue, as we understand it today, was born. As Virginians migrated to, and settled in, other parts of the American South, they took barbecue with them.

In the Northern colonies, British cooks didn’t quickly embrace the barbecue their counterparts developed in Virginia. Northern cooks often stuck to what they knew: the “ox roast.” This festive tradition in England dates to the Middle Ages. With this method, the ox carcass was pierced with a metal rod and cooked evenly before a fire, with a team of cooks slowly rotating the spit from each side. It was also a good way to feed a good-sized crowd, so the Northern colonists’ attitude was, “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”

Though some July 4th celebrations featured an ox roast, southern-style barbecue became the favorite meal. Thousands of Philadelphians ate thousands of pounds of barbecued beef and lamb after a July 4, 1788, procession through the city. Thomas Jefferson hosted a barbecue dinner in Paris for expatriate Americans on July 4, 1789, shortly before the French Revolution. On July 4, 1791, Joseph Ingraham, captain of the Hope, a fur trading vessel, barbecued a 70-pound hog for his crew on the beach of Washington Island in the Pacific Northwest.

On the mainland, Independence Day celebrations shared common elements: a military procession, a reading of the Declaration of Independence in its entirety, speeches by local politicians, toasts to local and federal dignitaries, music, fireworks, and a free meal for the masses—which was usually barbecue. These celebrations drew several thousand spectators, and barbecue was well-suited to meet their needs because it was scalable.

These events were usually hosted by prominent white men who covered all of the costs. These men secured the land where the event was held, procured all of the meat used (often this was donated), bought other supplies, and hired the workers. In many cases though, enslaved African Americans did the work of clearing the land, preparing the food and serving it to guests. These large and scalable barbecues could happen anywhere. It was a moveable feast that fed not just thousands of people, but tens of thousands of people. Typically, whites ate first, and the African Americans present ate afterward.

There were some key reasons why hosts might have preferred barbecue to an ox roast. Given the lack of refrigeration, the animals meant for a barbecue were kept alive until shortly before the event. Thus, smaller animals like pigs and sheep were easier to transport, butcher, and cook than a large ox. Also, the ox roast relied on heavy equipment that included metal and bricks. It’s a lot easier to just dig a really long trench for barbecue than it is to lug around and assemble what’s needed for an ox roast.

The final key factor that tied barbecue to Independence Day celebrations in the South was the key role of enslaved African Americans in preparation and cooking. For some whites, what distinguished a barbecue from a bunch of adequately cooked meat seemed to be the involvement of African Americans. In 1919, John Bell Keeble, while serving as the dean of Vanderbilt Law School, validated this sentiment when he addressed a national convention of architects who had gathered in Nashville, Tennessee: “Some things have always been typical of a Tennessee welcome. Some you will get, and some you will not get. A barbecue was one of them. I do not know whether altogether we have lost the art or not. So many of the old negro barbecue cooks are dead that a barbecue is a rather difficult matter to bring up to the old-fashioned standard.”

After the Civil War, Southern whites who supported the Confederacy harbored sore feelings about being on the losing side. Independence Day celebrations in the South dropped off because they reminded white rebels of their defeat. Some commentators feared that the holiday would disappear altogether in the American South. In 1874, the Louisiana Democrat editorialized, “[T]he glorious Fourth of July has come again and gone again, unhonored, unsung.”

But African Americans in the region continued to vigorously celebrate Independence Day with barbecue and fried chicken. In 1901, the Atlanta Constitution newspaper reported, “[T]he [Fourth of July] is here, as in most places in the south, given over to the negroes, who celebrate [it] in truly royal fashion.” By the 1920s, Southern whites were back to hosting civic celebrations of Independence Day.

The traditional gargantuan Independence Day festivities downsized in the 20th century in two significant ways. First, as Adam Criblez points out in his book Parading Patriotism, after the Civil War, people lost their appetite for huge gatherings and many opted to attend smaller gatherings or family events. Due to higher meat prices and having to pay actual wages for labor, as well as the logistics of pulling off such huge events, more and more communities shifted to smaller events—and they started charging people to attend in order to recoup their costs. These events still got a sizable number of attendees, sometimes numbering in the thousands, but they just weren’t on the scale of the massive feeds that had frequently taken place a century before.

Second, barbecue changed in the 20th century as well. The trench method fell out of fashion as cooks shifted to using brick-lined pits and cooking smaller cuts of meat. The brick pits allowed barbecuers to control more variables during the cooking process. And in urban environments, digging a hole would have been impractical or against health codes. Cooking smaller cuts of meat is also easier and less labor-intensive than cooking a whole animal. By the 1920s, more people were eating barbecue in restaurants or building barbecue pits in their back yards, paving the way for the kettle grills that would explode in popularity during the 1950s. Over the century, the connection between barbecue and Independence Day stayed in our national consciousness, but the meal itself moved from civic spaces to public parks and private homes.

There’s a lot more to the story of barbecue, much of it hotly contested: African methods of cooking meat outdoors and whether they did or didn’t influence American cooks, the various types of sauce, regional differences in the American South, and much more. Thanks to technological innovation, barbecue can now happen almost anywhere, and cooks feel free to throw anything on the grill. Yes, this includes hamburgers and hot dogs. That’s all right. Though I have my purist tendencies, I’m fine with barbecue reflecting a “melting pit” of food traditions. My own Fourth of July plate is usually piled high with pork spareribs, hot link sausages, chicken, baked beans, coleslaw, an ear of grilled corn, potato salad, and a nice, ripe wedge of watermelon for dessert.

For me, it’s about celebrating with friends, family, and loved ones. It’s also a chance to pause and reflect on what it means to “celebrate” a nation that still falls short of its promise, but one that I call home. I live in the country that I love, and I want it to be better. Perhaps having diverse people sitting at a table and enjoying barbecue in all of its glorious forms, even kosher and “vegan,” and respectfully discussing the issues of the day can be a first step to a more perfect union. When it comes to barbecue and the Fourth of July, what pitmasters and politicians have beautifully joined together, let no one pull asunder!

This article originally appeared at Zócalo Public Square. Primary Editor: Minal Hajratwala | Secondary Editor: Lisa Margonelli

Featured image: Shutterstock

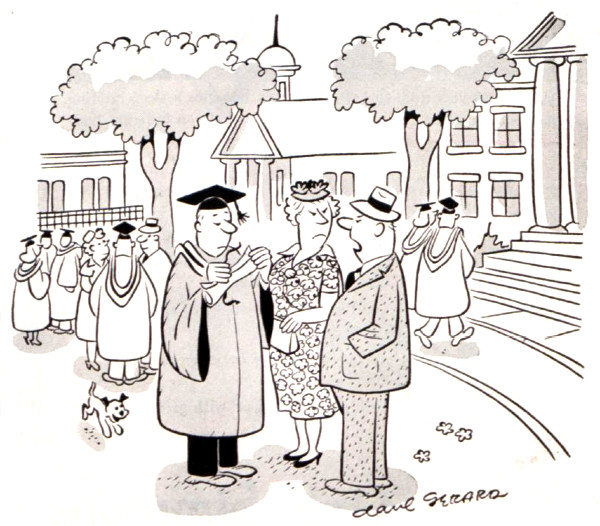

Cartoons: Dear Old Dad

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Goldstein

November 17, 1951

Harry Mace

November 15, 1952

Stan Hunt

September 13, 1952

Marty Lowenstein

August 4, 1951

Dave Gerard

June 2, 1951

Hank Ketcham

May 26, 1951

O’Brien

April 10, 1954

Larry Harris

February 2, 1952

Harry Mace

December 15, 1951

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

What Our Dads Did for Us

Each year when Father’s Day rolls around, I think of the late Erma Bombeck.

While she mined family life for years in her syndicated column and best-selling books, on June 21, 1981 — Father’s Day that year — she plumbed memories of her father for one of the most unforgettable columns ever to appear on the printed page.

If you think that’s a bit much, it was so good it was reprinted by Reader’s Digest. And in 1989, when the editor of Reader’s Digest undertook a special project to determine the best articles that had ever been published in the magazine — he went back and read through all 67 years of issues — Erma Bombeck’s Father’s Day column was one of them.

If you wonder why, consider her opening.

When I was a little kid, a father was like the light in the refrigerator. Every house had one, but no one really knew what either of them did once the door was shut.

For years I used Erma Bombeck’s Father’s Day column as an example of the power of the telling detail when I taught feature writing at the School of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of North Carolina (now the UNC Hussman School of Journalism and Media).

He opened the jar of pickles when no one else at home could.

He was the only one in the house who wasn’t afraid to go into the basement by himself.

A bit later —

It was understood that whenever it rained, he got the car and brought it around to the door.

When anyone was sick, he went out to get the prescription filled.

And —

He took a lot of pictures, but was never in them.

When we discussed it in class, students — year after year after year — would say, “My father didn’t do that. He cut the wood for the fireplace.” Or, “My Dad didn’t do that. He put up a backboard and hoop on the garage so I could shoot basketballs.” Or, “Daddy didn’t do any of those things. But when he made the popcorn, he put lots of butter on it.”

That is what fathers do.

That with time we come to appreciate, and recognize on Father’s Day.

While it’s been celebrated by Catholic institutions since the Middle Ages (March 19, St. Joseph’s Day), and President Woodrow Wilson tried to establish a national Father’s Day in 1913, it wasn’t until the 1930s that the idea gained traction, due in part to growing support from manufacturers and merchants who would benefit from the sale of items for fathers.

Still, many Americans continued to resist, viewing Father’s Day as nothing more than an attempt to replicate Mother’s Day. (I remember asking when Children’s Day was and being told, “Every day is Children’s Day.”)

The resistance would weaken with the years, but it was not until 1966 that the first presidential proclamation designating the third Sunday in June as Father’s Day was signed — by President Lyndon B. Johnson. In 1972 President Richard Nixon signed the law making it a permanent national holiday.

With my first Father’s Day gifts, I learned — with a little help from Christmas — never to buy my father ties. I might be young and still growing, but I picked up quickly on the fact that, however nice he was, however much he loved me, he’d rather pick out his own.

Like Erma Bombeck, it’s when I look back that I realize how much he did.

My father was the one who set and emptied the mouse traps. He stood alongside the Christmas tree in the lot, turning it slowly as my mother and I stood back, checking the symmetry, to be sure it was perfect. He spent his summer vacations painting the kitchen (or bedroom or bathroom), undoubtedly happy to get back to work.

He wasn’t a gourmet cook, or even your everyday cook, but on Sunday morning he went into the kitchen and made pancakes. He would let the batter spread out on the griddle into a near-perfect circle, then add a bit at the top of one — mine — like the stem on an apple. A “handle,” he said. Just for me.

As most fathers do, I suspect, he deferred to my mother on most of the things a parent can rule/guide/steer/suggest — especially, mothers with girls. But he insisted on two things.

1. I must know how to reconcile a bank statement. I do. But I don’t like to do it.

I like to think he would be as happy as I am that technology, i.e., my online bank account, has eased that almost into oblivion.

2. I must put my own worms on the fish hook. I did. But I’d never enter a fishing contest, however shiny the first prize trophy.

Did I mention he cleaned the fish?

My father did not run alongside my bike “for at least a thousand miles until I got the hang of it,” as Erma Bombeck’s father had, but we faced the same challenges of forward motion when he taught me how to drive. The most vivid and lasting memory that came out of that was my appreciation — and his, I daresay — for the invention of the automatic transmission, which would bear many names, the one I remember being Hydramatic.

I consider it up there with the discovery of fire and invention of the wheel.

Alas, it was still in the laboratory the afternoon Daddy took me out to a gravel country road, more specifically a hill with a considerable incline, and introduced me to the finer points of coordinating the clutch, the accelerator, and the brake.

It is an acquired skill.

Bob Newhart had a classic comedy routine on this trying form of human endeavor known as driver education that I heard on the radio one afternoon while driving on the Merritt Parkway in Westport, Conn., and laughed so hard I almost had to pull over. In that case, it was a paid instructor suffering the torment of a driver still in training.

My father did it for love.

And I love him for it.

And all the other things he did that time has turned to gold.

Little things.

Things that have survived the years, the day’s breaking news, the aches and pains of aging, to not only mean a lot. To mean everything.

Like the time — it was before Hallmark cards became the staple of Valentine’s Day — that I worked on a package of pieces for Valentines that you assembled yourself. My grandmother had bought the package for me, and this particular afternoon I was at her house working on the Valentines to present to my loved ones.

You had to paste the lace-y white sheets over the Valentines. They had little paper feet you attached appropriately. Although the paste that I used was homemade — flour and water in the proper proportions, which my grandmother knew — it worked on the little paper feet. They stuck nicely.

And that might have been the end of it except that when I finished I decided to make chocolate pudding for dessert that night. I was only seven, but I managed to reach the cookbook. I mixed the ingredients, found a pan into which I poured the pudding-to-be, and set the pan on the stove. A white enamel stove set up on cabriolet legs, the burners were chest high for me. The handles were on the front, though, so I could reach them. They were also white ceramic, and I turned the one in front of me. It was a gas stove, with flames that licked at the sauce pan.

I stirred. And stirred. And stirred.

When it didn’t thicken, I remembered the flour and water my grandmother had mixed for the paste for my Valentines. And creating a family story for years to come, put the paste in the pudding.

By the time we went to eat it, the pudding still looked like the chocolate pudding I had poured into the pretty glass dessert dishes. But it had taken on certain qualities and characteristics we associate with concrete. I couldn’t get my spoon into it, nor could most of the adults at the table. But Daddy chipped away … and chipped away … and chipped away until he had a spoonful. You could almost hear it clink as it went down.

He even managed a smile as he looked over at me and said, “It’s very good, honey.”

All photographs courtesy of Val Lauder

How Social Distancing Can Help Us Rethink Our Gatherings

Gatherings around the world are cancelled or postponed: Concerts, conferences, religious services, birthday parties, yoga classes, the Olympics, funerals. Almost all instances of people in proximity to one another have suddenly evaporated in the U.S. as many of us have been isolating in our homes.

While the COVID-19 pandemic has altered daily life for most everyone, Priya Parker thinks it has created an opportunity for us to reexamine the ways we connect with one another.

Parker is a trained conflict resolution facilitator who started using a process called “sustained dialogue” at University of Virginia to facilitate meaningful conversations and connections across racial and ethnic barriers. As a biracial woman, she noticed a lack of understanding around race on campus, and she decided to do something about it.

In 2018, Parker published The Art of Gathering, a book that calls on us to reconsider the gatherings we plan and attend, from celebrations to meetings to mass events to dinner parties. Parker’s book offers a new way of determining how we should shape these gatherings into meaningful experiences instead of routine events. She writes that “We spend our lives gathering … and we spend much of that time in uninspiring, underwhelming moments that fail to capture us, change us in any way, or connect us to one another.” Parker believes that we can change this, though, even — and maybe especially — in a time of global crisis.

Her new podcast, Together Apart, produced with The New York Times, tells the stories of people navigating our new reality in their own attempts to gather safely and .

In our interview with her, Parker shared her philosophy of getting people together, socially distanced or otherwise.

SEP: You talk in your book about our “ritualized gatherings” and how they’ve been repeated so much over time that we’re attached to the forms of our gatherings even after they no longer reflect our values. What are we doing wrong when we gather?

Priya Parker: We skip over asking what the purpose is. So, we skip too quickly to form. If we’re hosting a baby shower, we assume it has to look a certain way and skip to buying or making the baby games. I wrote about the New York Times “Page One Meeting” in the book, which continued for more than 70 years even after it no longer made sense to have the biggest meeting of the day focusing on what goes on page one, since they now had this thing called the home page. Whether it’s a baby shower or an editor’s meeting, the biggest mistake that we make when we gather is to assume that the purpose is obvious.

SEP: To zero in on the purpose of gatherings, you suggest finding a “disputable purpose” and even excluding people if necessary, in the right way. A lot of us are rule-averse and want to at least appear laid back when we’re planning gatherings, so how do you think we can start to embrace rules like this?

Parker: I would differentiate between principles and rules. I think something like “know why you’re gathering” isn’t a rule; it’s a principle. It’s not controlling or uptight to be asking “why are we doing this?” It’s intentional.

But I do, in the book, write about pop-up rules. Something like practicing generous authority. Something we tend to do in our gatherings is “underhost.” In wanting to not seem too controlling or bossy, we kind of do nothing. This is an argument to say that if you’re interested in creating transformative, memorable gatherings, the way to do that is to have a specific purpose and to create a sequence or structure — that can actually be delightful and fun.

If the purpose of a baby shower is to help a couple figure out how they want to parent when they’ve never seen a model for that in either of their families before, having a baby shower with all women and pinning the diaper on the baby is not going to help you fulfill that purpose. Gathering is a form of power and it’s also the way we spend our time. I’m not so much an advocate of rules so much as I am an advocate of not wasting people’s time.

SEP: Let’s say you’re at a terrible gathering. You know it’s terrible, and everyone else does too, but you’re not the host. Is there anything you can do as a non-host to make a gathering better?

Parker: I called this book The Art of Gathering and not The Art of Hosting, in part, because I think guests have a lot of power. I know of this retirement party that happened pre-COVID, and the team of a department was invited to a retirement lunch, and everybody came and sat down and they were chatting. The person who sent out the invitations was planning to bring out a cake and a plaque at the end, but there were like two hours before that, so everyone was just kind of waiting around while nothing happened and it was a little embarrassing for the person being honored. Then, one of the guests stood up and clinked their glass and started a round of toasts and stories. It was a risk, right? But people went along with it. It gave structure, and completely transformed the event. Through their intervention, that guest transformed something that was mundane into something that was meaningful.

Sometimes it isn’t obvious who the host is, like if you’re at a conference or something and you’ve spontaneously come together with whoever you’ve bumped into. You can intervene and say, “I’m here because I’m new to the industry. Would you guys be up for a conversation?” and go around answering an interesting question. You have a lot of power as a guest to shape an outcome. Part of it is saying “there is a beautiful conversation that could happen here. How do we have it?”

SEP: I think it’s a little more common these days to come across the idea of introvertedness or social anxiety, and some people say they don’t like to be in gatherings or that they don’t like to be around strangers. But you say in your book that “everyone has the ability to gather well.” Does that run counter to the idea of introvertedness?

Parker: One of the things I found interesting writing this was that I interviewed over 100 people for this book who people described as transformative gatherers — in all different fields, a rabbi, a choir conductor, a hockey coach, a photographer — and many of them identified as introverts or sufferers of social anxiety. One of the things I found, at least anecdotally, is that often introverts — people who don’t like to go to gatherings — are some of the best gatherers. This is because they’re creating the gatherings they wish existed.

When you’re designing experiences for other people, I think it’s almost dangerous to rely on a very charismatic personality to lift the group and carry it through something. When you create thoughtful structure, you don’t actually have to do very much once people arrive. I actually think that often when people don’t like going to gatherings, they’re on to something. They don’t like them when they’re really awkward and they aren’t guided with care. They don’t like gatherings where you have to keep introducing yourself or try to prove your worth. It’s exhausting. But there is another way to do this, and, in my experience, introverts and others who are on the outside of communities are really amazing, thoughtful gatherers.

SEP: When it comes to family and friends with really polarizing politics (I think everyone thinks about this around Thanksgiving for some reason), a lot of strategies go around for gathering people like this and keeping conflict at bay. How would you approach gathering people where politics differ and maybe even values differ as well?

Parker: I think first, again, is know the purpose. Is the purpose to engage in politics? Or to have a good time? If you’re trying to interstitch a community and they’re divided on politics, as a conflict resolution facilitator, one of the things you know is that there are different tools for different conflicts. It may make sense to avoid conversation as a centerpiece of your gathering. It may make sense to do it in a sports league or volunteer together. There are a lot of ways to build relationships, and things that allow people to see different sides of each other are going to help to build that community.

When you’re bringing together people who are different, don’t try to make them the same; try to complicate each side. Krista Tippett said “We assume a monolith of the other that we know not to be true of our own side.” So we think “all evangelical Christians … ” or “all white women …” or “all Muslims … ” whereas we know that there’s so much difference even within our own families.

If you’re going to go for it, my suggestion is to ground a conversation around stories, not opinions. Or, don’t focus on conversation and find a meaningful activity that allows people to show different sides of themselves. People could think, oh wow, he is just as competitive as I am, or, she’s also superstitious. We all have different sides to ourselves, so part of loosening that knot isn’t to focus on stamping out the differences but to bring out the complications of each side because they have something in common.

SEP: I find it ironic that you’re book about gathering has just come out in paperback while we’re all social distancing.

Parker: It is an ironic time to deeply understand gatherings when the world is ungathering.

SEP: But you do have this podcast called Together Apart, so I want to know some innovative or inspirational ways you’ve seen people connecting during this pandemic.

Parker: People are finding really beautiful ways to gather even with social distancing. In this week’s episode, which was on birthdays, an aunt and her nephew organized a birthday party in a parking lot for all of the neighbors and asked them to park their cars in a circle and blare pop music and honk as the birthday boy was going to drive through. It was totally amazing to have a release of joy when people are cooped up in their houses, but in a safe way. One interesting thing I’ve been getting a lot of notes on is people living in neighborhoods all over the country who don’t know their neighbors, and all of the sudden, Facebook neighbor groups are popping up saying, “drinks on the lawn, 12 feet apart, 5 p.m.”

One powerful thing we’ve been seeing online is people whose gathering is unique to this time and wouldn’t make much sense in other times. D-Nice, this D.J. in Miami, started spinning sets three weeks ago, and some of his dance parties are 100,000 people. Michelle Obama stopped by, Bernie Sanders, Mark Zuckerberg stopped by, but it was literally open to everybody. It was a strange combination, that I think is difficult in in-person gatherings, of elite and deeply democratic while allowing these psychological V.I.P.s through the door. It reminded me of a quote from Studio 54 when Andy Warhol was criticized for the red rope, and he said “It’s a dictatorship at the door so that it can be a democracy on the dancefloor.” I think D-Nice is this fascinating example of being a democracy at the door and a democracy on the dancefloor.

There are virtual choirs, collective spin classes and knitting classes, Alcoholics Anonymous, happy hours, and everything in between. And I think families are trying to figure out how we can be together apart in a way that’s safe but still specifically marks a moment in our lives.

SEP: Do you think this is a good time to reconnect with old friends?

Parker: Absolutely. This is a massive, generational, global interruption, and it’s a painful one. It makes us pause and think, who do I love? What have I not been doing when I was overbusy? Beyond the question of reconnecting with old friends, it’s really a good time to reconnect with how you want to live. Part of that is who you want to be part of that life.

SEP: What do you hope people take away from your book?

Parker: My deepest hope is that people pause, at work or home or in the public square, and think more intentionally about how we do things together, and then have the courage and the permission to go invent that new way of being.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Logophile: So Much to Love

The word logophile stems from the Greek roots logos “words” and philein “to love” — a logophile is someone who loves words. But there are so many things in this world to love! Can you match up these other –philes with the objects of their affection?

Match the Word with the Thing Loved

-

- An anthophile loves …

- An ailurophile really appreciates …

- A chionophile is keen on …

- A cinephile quite enjoys …

- A cynophile just adores …

- An oenophile can’t get enough of …

- A pogonophile treasures …

- A selachophile is enchanted by …

- A selenophile prizes …

-

- beards

- cats

- dogs

- flowers

- the moon

- movies

- sharks

- snow

- wine

Answers

- d

- b

- h

- f

- c

- i

- a

- g

- e

This article is featured in the January/February 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock

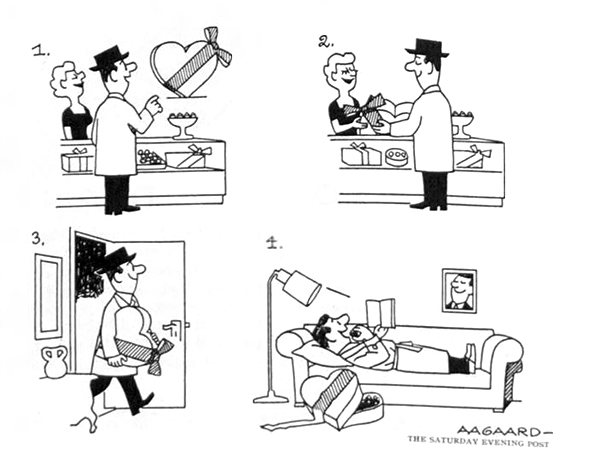

Cartoons: Be My Valentine

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

February 23, 1960

Al Piane

February 13, 1965

February 13, 1954

Taber

February 9, 1963

Bob Schroeter

February 9, 1957

Dan Q. Brown

February 13, 1954

Mort Gerberg

February 11, 1967

Want even more laughs? Subscribe to the magazine for cartoons, art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Are There Too Many Holidays?

You’ve gotta love holidays. Many people say that. I’m not one of them. I acknowledge holidays and I honor your right to celebrate them, including the truly absurd ones. But I don’t have to embrace them. You cannot make me.

Among other things, we have way too many: official national holidays, religious holidays, and all those kooky holidays invented mainly to enrich merchants. You want to go all gooey over National Pepperoni Pizza Day? Fine, but don’t expect me to send you a greeting card.

So here we are, with the big winter holidays just behind us. (And I ask you, seriously, is Christmas still a religious holiday in America or is it chiefly a gift-giving festival that drives personal debt?) Valentine’s Day — not to be confused with Sweetest Day, which is the third Saturday in October — is straight ahead. Now, let’s be real: V-Day has devolved into little more than an excuse to sell massive quantities of chocolates and roses, mostly to guilt-ridden men. Do you naively believe it is mainly intended to applaud romance?

You see where I’m going here? So many of our holidays are a crock. And our best one, Thanksgiving, sort of gets lost amid all the hoo-ha that precedes the month of Christmas (sometimes known as December).

Our national affection for holidays large, small, and preposterous has grown so ludicrous that today you can even invent one and purchase rights to it. You heard me correctly. A company called National Day Calendar will gladly promote your holiday nationally, and it’s good at doing that. At one point the getting-in fee was $1,500; the company won’t disclose what it charges nowadays.

Indeed, it’s the proliferation of fake holidays that overwhelms the few legitimate ones. Arbor Day, which I regard as meaningful if minor, gets crowded out in the public’s mind by the silliness of Hairball Awareness Day, Hug a Plumber Day, National Prime Rib Day, and the like. The lame-o holiday industry is thriving. There’s no chance it’s going to sputter anytime soon.

You want to go all gooey over National Pepperoni Pizza Day? Fine, but don’t expect me to send you a greeting card.

Some statistics: Ranking holidays by the most cards mailed, Christmas easily lands in first place (151 million); Valentine’s Day, second; Mother’s Day, third. The shocker is that Halloween comes in sixth (17 million cards sent). Really, people share Halloween greetings in those numbers?

Let’s take a look at the holidays that most efficiently pick our pockets. Not surprisingly, Christmas season again holds first position ($626.1 billion spent, according to a recent tally); Easter comes in a few places down at $16.4 billion, just barely ahead of the Super Bowl, which, yes, is regarded as a holiday by industry watchers. Father’s Day limps in at $12.7 billion. That’s roughly half of what Americans lay out for Mother’s Day. Ah, poor dads.

Another un-fun thing about holidays is that they can trigger stress. No one likes stress. But many of the bigger holidays, no matter how you try to avoid it, require some “family time.” To be especially dreaded are sleepovers. I’ve seen one study that says 65 percent of respondents were decidedly opposed to staying at a relative’s home overnight during a holiday event. My question: Only 65 percent?

Even worse, if you can avoid visiting with family, you may be stuck spending time with your very own self. Talk about unpleasant! “That’s the problem with holidays: they give you time to reflect on life,” a writer whom I respect recently wrote in a daily paper. “Reflecting on life can soon spin out of control.”

So if you are someone who, like me, believes we are appallingly over-holiday’d, I ask you to be patient for just a bit. We can protest, in unison, on March 7 — National Be Heard Day.

In the last issue, Cable Neuhaus wrote about the troubling rise of noise pollution.

This article is featured in the January/February 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Bring Them a Figgy Pudding

Having grown up in a small town and regularly attending its Methodist church, it has never occurred to me that a church service could be crowded or, heaven forbid, full. So when I marched into the Unitarian Universalist Church to attend a winter solstice celebration, promised to be “a night that ranges from meditative to raucous,” I was shocked to learn that there was no room at the inn.

Like the three wise men, I had come bearing gifts — a homemade figgy pudding — and like the virgin Mary, I was turned away. I was about fifteen minutes late, and the greeter was only acting in accordance with the city fire code. And it wasn’t a real figgy pudding.

Similarly to Joan Didion, I think of myself as a “can-do” person. Particularly around the holidays, I am inspired to open my oldest bottle and bake up seasonal confections in the traditions of the days of old. Last year, I made a fruitcake. This year, I planned to tackle the elusive figgy pudding.

The only problem is that figgy pudding appears to be little more than a holiday lyric.

At least, that seems to be the case with this dessert that everyone sings of and no one actually eats. The archives of The Saturday Evening Post make no mention of a popular dish called figgy pudding, but NPR explored the history of figgy pudding several years ago, and they maintain that it is, indeed, real and edible. The recipe they provide calls for beef suet, five to six hours of boiling, and — ideally — four to five weeks of aging. If you have that kind of time and enterprise, then, by all means, whip up the Victorian treat during a movie marathon.

Instead, I opted for a bread pudding recipe from the January 28, 1913, issue of this magazine. In “Old Bread in New Puddings,” Elisabeth Irving makes a convincing, if dubious, case for making bread pudding from all of those leftover bread crumbs that would be found in the early century home: “It seems to us that if, instead of the inevitable pie and cake so constantly served on some farm tables, the farm housewife, when concocting desserts for her family, would oftener utilize some of the fragments of bread that usually go to waste, in connection with the abundant milk and eggs always to be had on the farm, there would be better nourished bodies and less stomach trouble, and consequently fewer doctor bills.”

Having made the famous Thanksgiving classic, persimmon pudding, recently, I was in abundance of buttermilk (make Eva Powell’s award-winning recipe with very ripe persimmons, if you can get them, and serve it with whipped cream and a dusting of cinnamon), but I haven’t found myself baking loaves of bread lately, so I dried bread crumbs from store-bought baguette. I made the “Chocolate Bread Pudding” (see the flipbook below) from our archives, but I made a few changes, rendering Dark Chocolate Bread Pudding with Blueberry Preserves and Mandarin Orange Meringue.

The blueberries were an accident. I grabbed a jar in haste at the grocery store, thinking it was cherry preserves. When I arrived at home and discovered my mistake, I decided I would have to live with it. If medieval homemakers could mix meats and fruit, then I was allowed to get creative with dark chocolate.

The beauty of bread pudding is, just as Elisabeth Irving puts it, “there are so many possibilities, for the ingenious cook who takes a little trouble that there is no excuse for lack of variety in that direction.” Bread pudding is like sweet stuffing. You can throw anything you’d like into it. If you want to toss in dried figs (first cooked in brandy) and sing about your perfectly appropriate pudding, you can!

After my pudding and I were denied entry to the pagan celebration, I took it to a friend’s Christmas party. I had a vision of waltzing in with my festive dish, dousing it in brandy, and setting it aflame as the other party guests applauded my culinary achievement. When I arrived, the house was so packed full of people I could barely squeeze through to the dessert table. I searched for my friend, a student of performance art at the New School back home for the holidays, and ended up striking conversations with various lawyers while keeping one eye on my untouched bread pudding.

Would the other guests love it? Hate it? Would they wonder aloud who possibly could have created the dark chocolate bread pudding, announcing the taste of fruit and zip of citrus that ties it together so nicely?

When I finally found my friend, he introduced me to other, college-age, interesting people. They were involved in theatre or fashion and had the excited spark of students in their early 20s. One of them was terribly fit, and I learned that it was because he was a tightrope performer at École nationale de cirque in Montreal hoping to join Cirque du Soleil. My friend told me he was going to perform a piece of performance art in ten minutes. “It’s a very interactive performance,” he said. Oh no, I thought.

I hadn’t the time or the patience with the crowd to make my way back to the pudding to see if it had been devoured, perhaps fought over. My friend gave his performance, a combination of audience interaction and audio recorded on a day he had zip-tied himself to a fence in Manhattan. We maintained eye contact with strangers for ten minutes and shared how we felt about the sounds of our own names. Then he instructed us to find a spot around the room and to lie down. He told us to hold hands with the person closest to us. This is taking longer than I expected, I thought. I wonder how that pudding is doing. The person closest to me was the tightrope acrobat. I hadn’t said much to him up until that point, but we followed directions, grasping hands while lying in opposite directions.

Immediately after assuming a grip, I realized it was the most uncomfortable position possible. But it would also seem too imposing (or too intimate?) to spend time finding a better position for my hand. Minutes passed as the audio played. I realized I was slightly hovering my hand off the floor quite awkwardly, and it was starting to go numb. My partner stayed perfectly still, so I didn’t want to break anyone’s concentration. Of course he’s excelling at this, he’s an acrobat, I thought. He’s used to these kinds of endurance tests. Then I realized my palms were sweating. On the audio, a street drummer played an entrancing rhythm on buckets and bells while the wind ripped across the microphone. I wanted to check on the pudding.

Afterwards, I poured a glass of wine to the brim and headed to the dessert table. The pudding was gone! And its plate washed and drying in the kitchen. I would never know if the serving dish had been desperately licked clean by lawyers’ children who would be forever haunted by the mystery dessert they could never find again. Then, I realized I didn’t even know for myself whether the bread pudding was as delectable as I imagined, because I never got a piece. I chewed some peppermint bark and said my goodbyes, preparing for more intrusive thoughts about the best bread pudding I never had.

Dark Chocolate Bread Pudding with Blueberry Preserves and Mandarin Orange Meringue

- 2 cups bread crumbs

- ¾ cup sugar (plus 1 cup for meringue)

- ¼ cup molasses

- 4 tbsp butter

- 1 pint milk

- 1 pint buttermilk

- 4 eggs

- 6 tbsp dark chocolate powder

- Blueberry preserves (or raspberry or cherry)

- Pinch of salt

- 1 mandarin orange

Directions

- Melt butter, and stir in ¾ cup sugar. Add in molasses, milk, buttermilk, dark chocolate powder, bread crumbs, and salt.

- Separate egg yolks and stir them into the batter, taking care that the batter is not too warm from the melted butter. Save the whites for the meringue.

- Pour into a baking mold, and bake at 300 F for about 2 hours.

- Make meringue using the egg whites, 2 tbsp of juice from the mandarin orange, and 1 cup of sugar, added slowly.

- Once it is set, flip the pudding out of the mold. Using a filling syringe, pipe blueberry preserves into the pudding through the top, making your way around. Cover the top with meringue piled high. Broil in the oven, watching closely, for a few minutes to brown the meringue.

Featured image: Shutterstock.

Rockwell Video Minute: Rockwell and Charles Dickens

See all of the videos in our Rockwell Video Minute series.

Featured image: Norman Rockwell / SEPS

Hallmark’s Formula for a Very Sappy Christmas

In the new Hallmark movie Holiday Date, Brooke has been dumped just before Christmas by her sleek, professional beau — he’s “going to be really busy with this project” — and her English-accented boss poo-poos her classic clothing designs in favor of more “cutting edge” fashion. Joel is an actor up for a big role playing a small-town hero, and their friends think it’s a good idea for Brooke to take him back to her hometown, Whispering Pines, for the holidays to pose as her boyfriend. “I can’t believe we’re doing this,” Brooke says as they cruise across the wintry landscape in a baby blue Mini Cooper. He lets out a fake boyfriend chuckle: “I know, it’s crazy, isn’t it?”

It’s not that crazy, though.

At least, not in the Hallmark cinematic universe. The phony boyfriend or girlfriend plot device also appears in Holiday Engagement, The Mistletoe Promise, Hitched for the Holidays, A December Bride, Snow Bride, and A Christmas for the Books, to name a few.

By now, Hallmark is a well-known holiday movie machine. This year is the 10th anniversary of Hallmark Channel’s “Countdown to Christmas,” a two-month-long nonstop marathon of garland-wrapped, hot cocoa-fueled, gentle holiday romance. The greeting card company — through their subsidiary Crown Media — has effectively cornered the market on Christmas cable programming for younger and middle-aged women, and this year they’ve released 40 new Christmas-themed made-for-TV movies between their networks Hallmark Channel and Hallmark Movies & Mysteries.

This past summer, I visited my parents, strolling into my childhood home and beholding — on their new flat screen TV — a cheesy Christmas movie. In July! I accosted my mother, wondering how she could live with herself watching Hallmark Christmas movies during tomato season. But they were running a special marathon, “Christmas in July,” and she wasn’t alone in cozying up to holiday movies with the air conditioner running. What could possibly be the appeal of these movies? I thought to myself as we sat through the third one in a row.

“If you’ve seen one, you’ve seen them all” was never more applicable than to the Hallmark oeuvre. (2014’s A Cookie Cutter Christmas displayed an eerily self-aware title.) Any fan of the franchise is well aware of the formula: a man and woman meet under awkward circumstances, stumble slowly toward romance, and finally share a brisk kiss under the glow of a thousand Christmas lights. There are recurring themes, like the virtues of slower, small-town life over the cold, hectic city, or the importance of listening to your heart and following where it leads (incidentally, it leads an inordinate segment of Hallmark characters to stake out their lives in pastry bakeries and tree farms). The most important virtue, however, is the love of Christmas and belief in its fateful magic.

The company has fashioned its own film genre out of wealthy suburban culture and happy endings, but it didn’t always used to be that way.

In fact, the last decade or so of Hallmark’s television programming is a departure from their media legacy. Since the dawn of broadcasting, the company has been known for culturally significant, acclaimed drama. Their pivot to feel-good seasonal romance says as much about the Hallmark brand as it does about us, the viewers, and what we hope to gain from watching them.

In the 1930s and ’40s, after a few decades of success selling greeting cards and wrapping paper, the Hall brothers of Hallmark decided to get into the radio game. They began by sponsoring shows like Tony’s Scrapbook, a folksy poetry program that a 1932 Time magazine review claimed was “regarded by a shuddering minority as the most offensive broadcaster on the air” for the host’s sentimental, rustic demeanor. Hallmark also sponsored Meet Your Navy and Radio Reader’s Digest as the company navigated national growth.

Then, in 1948, Hallmark went off on its own with Hallmark Playhouse, a radio drama program to replace their partnership with Reader’s Digest. Hallmark Playhouse was to be a new kind of show, one that delved into the annals of literature to find worthy, sometimes obscure authors and titles for dramatic readings, with author James Hilton, and later Lionel Barrymore, as the host. Hallmark Playhouse broadcast readings of Edna Ferber, Carl Sandburg, and Ring Lardner with stars like Irene Dunne, Bob Hope, and Gregory Peck lending their voices. Stephen Vincent Benét’s “The Devil and Daniel Webster” and Rose Wilder Lane’s Free Land (both found in the pages of The Saturday Evening Post) were also dramatized on Hallmark’s acclaimed anthology show.

On December 22, 1949, “The Story of Silent Night” aired, dramatizing the origin of the Christmas song, with a children’s choir, sound effects, and original music by Lyn Murray. Media scholar John V. Pavlik wrote about how the episode underscored “the extraordinary resources, intellectual capital, and pure talent that went into creating a program such as the Hallmark Playhouse, a program that consistently produced the highest levels of production quality and value.”

Two years later, in August 1951, founder J.C. Hall excitedly announced to the company that Hallmark would “try our hand at television.” Corporate sponsorships of television dramas were common. In Texaco Star Theater, Milton Berle was hosting an unpredictable hour of comedy and music, and Goodyear (or Philco) Television Playhouse brought original drama to the screen from up-and-coming writers and actors. The first Hallmark Television Playhouse broadcast was on NBC on Christmas Eve, 1951, and it was unlike anything seen on American television before. Amahl and the Night Visitors was a live opera, composed for television by Pulitzer winner Gian Carlo Menotti, telling the story of the three wise men from the point of view of a young peasant boy.

Hallmark Television Playhouse (and later Hallmark Hall of Fame) aired weekly for several years, before scaling back to monthly, then seasonal, episodes. Throughout the ’50s and ’60s, the series became a unique television event, bringing classic stories and big actors to the small screen. Maurice Evans played Richard II, Judith Anderson played Lady Macbeth, and Christopher Plummer and Julie Harris starred in A Doll’s House. Hallmark claims that more people tuned in for the 1953 broadcast of Hamlet than had cumulatively seen the play performed on stage in 350 years.

Although many programs from the “Golden Age of Television” disappeared, Hallmark Hall of Fame held strong. The format and content changed, but the series continued to present classic stories and problem dramas on primetime TV with big-name actors. In 1986, James Garner and James Woods starred in Promise, a drama depicting the arduous task of caring for a sibling suffering from schizophrenia. Far from saccharine, Promise holds up as a sensitive portrayal of the toll of mental illness on relationships. The film got a DVD release, but you won’t find it, or virtually any other Hall of Fame movies, on any streaming service.

In a 2009 CBS story on the enduring legacy of Hallmark Hall of Fame, Ron Simon, of the Paley Center, said “Hallmark has been around almost the entire history of American broadcasting, it’s one of the few institutions that sort of remain unchanged from postwar America into 21st-century America.” The Hall of Fame series has won 81 Emmys, the most recent of which was 2009’s The Courageous Heart of Irena Sendler.

Their ratings began to falter however, and in 2011, CBS dropped the program. Hall of Fame found little success at ABC, and, eventually, Hallmark moved the franchise over to their own cable channel, where they’d already been experimenting with a new strategy for made-for-TV movies that didn’t require period costumes, classic scripts, or much dramatic conflict at all.

The most recent Hallmark Hall of Fame release is called A Christmas Love Story. Starring Kristin Chenoweth and Scott Wolf, the story follows an ex-Broadway star who finds love, and inspiration for a new song, while teaching a children’s choir in New York City. Aside from some long-lost-parent drama, the film is nearly indistinguishable from Hallmark’s other holiday fare, with all of the same Christmas glitz and cloying courtship as A Shoe Addict’s Christmas or Two Turtle Doves.

Michelle Vicary, the executive vice president of programming for Crown Media, recently told Parade magazine that “People need to feel good and they need comfort, so, it’s an honor to bring that to people.”

Even though we’re familiar with all of the actors, we can predict the plot, and we might even recognize that gazebo in the final scene that’s lit up like an oversized tanning bed, we keep watching, year after year. And Hallmark knows it. They hope to capture the hearts of 100 million viewers this year over last year’s 85 million.

Hallmark has expanded its holiday offerings, and last year they released the Hallmark Movie Checklist App to help viewers keep track of the listings. This year, Hallmark sponsored the first Christmas Con in Edison, New Jersey, where fans could meet some of their favorite Hallmark stars and bask in some curated Christmas cheer.

Online, Facebook groups, numbering in the tens of thousands, are filled with Hallmark fans — mostly women — posting about their favorite movies. Many of their interactions muse on the movies’ similarities or the attractiveness of male leads. Others share photos of their decorated Christmas trees or a serendipitous snowfall right before the holidays.

I talked to Jennifer, 36, from Durham, North Carolina who moderates a subreddit group dedicated to Hallmark Movie fans. “I used to like watching Lifetime movies,” she says, “but they started to get a little too ridiculous and dramatic, so I had to walk away. I started watching Hallmark Hall of Fame movies at night when I couldn’t sleep, and they just made me feel at home, no matter how depressed or sad I was.”

Jennifer was orphaned at a young age, so she says she enjoys watching a family in a Hallmark movie having a nice holiday. Also, her 12-year-old son is autistic, and she says the movies inspire her to make Christmas special for him by doing things like baking cookies and decorating a tree. “I just love how sappy Hallmark movies are,” she says. “Everything is always alright at the end, which is just the opposite of real life.”

For Hallmark, the promise of comfort might be increasingly more difficult to keep.

Hallmark has faced criticism about the lack of diversity in their casting, and, just recently, they came under fire for taking down ads that featured two women kissing (Hallmark has since reinstated the ads and apologized). In the most current incarnation of Hallmark’s made-for-TV world, divisive politics don’t exist, along with poverty, mental illness, or war. The worst fate a Hallmark character could succumb to is working late on Christmas. Hallmark’s preoccupation with manicured small towns and contrived joy begs the question of whether they’re selling nostalgia or fantasy.

In Holiday Date, when Brooke’s pretentious European boss tells her she should design edgier clothing, the winsome blonde snaps back: “You know, the history of fashion shouldn’t be ignored. There’s a lot to be learned from the past and how it shapes who we are.”

“Of course that’s true! But you’re only inventing a past that comforts you!” I shouted at the television. And my mom told me to shut up and enjoy the movie.

Featured image: Shutterstock

In a Word: Eight, er, Nine Tiny Reindeer

Today, we all know the names of Santa Claus’s nine flying reindeer — or at least we think we do. But what is behind those names, and which ones have changed over the last 200 years?

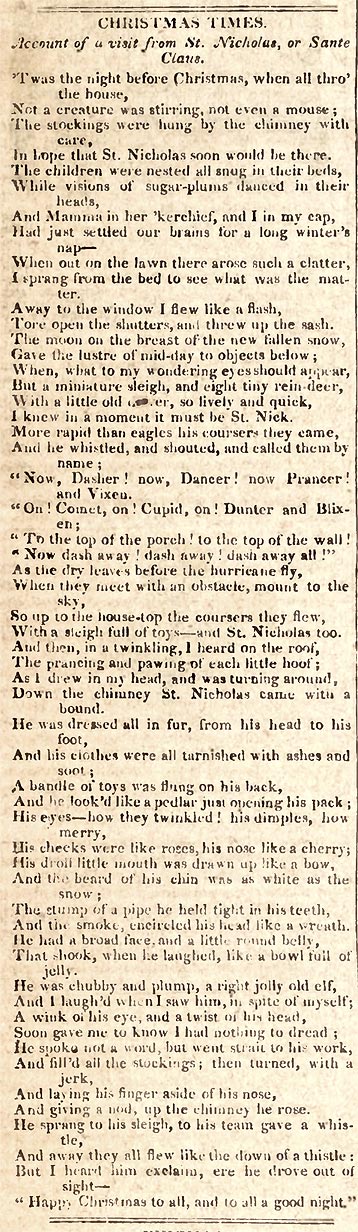

January 7, 1826

The names of eight of those reindeer first appeared in the poem we know today as “The Night Before Christmas.” It was first published anonymously on December 23, 1823, in a newspaper in Troy, New York and became an immediate hit that was published and republished for years in papers across America under the title “A Visit from St. Nicholas.” The Saturday Evening Post even printed it in its January 7, 1826, issue.

But the man responsible for penning the poem remained a mystery until 1836, when Clement Clark Moore, a Bible professor from New York City, took credit for it. He even included it in a volume of his poetry published in 1844. However, the family of another New Yorker, Henry Livingston Jr. — who died shortly after the poem’s first publication and before Moore took credit — have long claimed that he was the poet. More recent research has reinforced that argument.

Regardless of who wrote the poem, it is the first to include Santa’s reindeer and call them by name. They weren’t names passed down from Old World folklore, but were created by the poet. Whether they were chosen for their meanings, their colloquial connotations, or simply for their rhythm and rhyme, we’ll never know. But the names do have some history, and they perhaps aren’t all exactly as you remember them.

Dasher

A dasher is simply one who dashes. Dash appeared in Middle English as dasshen in the 14th century, probably from the Middle French dachier “to drive forward.” Two types of “dashing” appeared in English at about the same time: There’s the “moving quickly” dashing, as in “dashing off to the store,” and there’s the “striking suddenly and violently” dashing, as in “being dashed against the rocks.” The poet probably had speed in mind when he chose this name — it is, after all, a poem for children — but some writers do have a knack for slipping in opaque little adult-themed jokes in their children’s stories.

If there is an adult insinuation here, there’s an even more frightening possibility. By 1800 — meaning it likely would have been known to the poet — dash was also being used as a euphemism for damn. Considering that Santa Claus’s raison d’etre is to be extremely judgmental of children, having a reindeer that hints at the ultimate naughty list wouldn’t be out of place. (It’s unlikely, sure, but not implausible.)

Dancer

Dance — from which the name Dancer is formed — has an unexpectedly muddied history. We know it entered Middle English in the 1300s as dauncen, from Old French dancier “to dance,” but that’s where certainty stops. Though French is well known as a Romance language — that is, it’s derived from the language of the Roman Empire — dancier isn’t derived from Latin: The Latin word for “dance” is saltare. Etymologists aren’t certain exactly where dancier came from; it’s possibly from an old Frankish dialect that predates the expansion of the Roman Empire into northern Europe.

Prancer