Your Health Checkup: The Unintended Health Consequences of a Pandemic

“Your Health Checkup” is our online column by Dr. Douglas Zipes, an internationally acclaimed cardiologist, professor, author, inventor, and authority on pacing and electrophysiology. Dr. Zipes is also a contributor to The Saturday Evening Post print magazine. Subscribe to receive thoughtful articles, new fiction, health and wellness advice, and gems from our archive.

Order Dr. Zipes’ new book, Bear’s Promise, and check out his website www.dougzipes.us.

COVID-19 has disrupted practically every aspect of life on earth as we know it. The rate of infection and mortality from this coronavirus is appalling, especially in the U.S., with numbers worsening as we head into the winter flu season. There are more than 8 million cases and 220,000 deaths, perhaps reaching 400,000 by year’s end. Many hospital ICU beds are full.

Scientists have told us what to do: wear a mask, keep your distance, avoid large gatherings, wash hands, and stay outdoors as much as possible when socializing.

But so many people battle these simple measures. It reminds me of initial resistance to wearing seatbelts in cars or helmets on motorcycles. The spurious objection that these requests encroach on civil liberties is absurd. Licenses are required to drive, own a firearm, hunt, fish, and do a myriad of other things. Why are these requirements not an intrusion on civil liberties, but wearing a mask is?

In addition to the obvious impact on our daily activities, COVID-19 has exerted unintended consequences that can pose long term risks to our health. Americans have scaled back multiple health care initiatives to an alarming degree.

Vaccinations have plummeted, even as we enter the flu season. Critical childhood vaccinations for hepatitis, measles, whooping cough and other diseases have declined significantly. Measles was already increasing before this year, possibly due to the growing strength of the anti-vaccination movement. Fewer children vaccinated because of coronavirus fears could worsen the trend. Childhood immunizations fell about 60 percent in mid-April in 2020 compared to 2019, ranging from 75 percent for meningitis and HPV vaccines to 33 percent for others like diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis.

Screening colonoscopies are almost nonexistent as are other preventive health care procedures like prostate checkups, mammograms, Pap smears and glaucoma evaluations. Routine doctor office visits have declined greatly. The potential consequences are an increase in vision loss; colon, breast, and prostate cancers; communicable diseases like measles and mumps; and reduced screening for illnesses like hypertension, diabetes, and coronary disease.

Equally or even more alarming is a decline in hospital admissions for acute illnesses like heart attacks. For example, a multicenter survey in Italy found almost a 50 percent reduction in admissions for acute heart attacks compared with the equivalent week in 2019. The decreases were associated with parallel increases in mortality and complication rates. Similar trends have been noted in England, the U.S., and other countries as well.

COVID-19 has frightened patients from seeking medical help for life threatening problems, as well as from preventive measures. We cannot let the trend continue. As we’ve heard in countless newscasts from scientists such as Dr. Anthony Fauci, the nation’s leading infectious disease expert, we as a nation must come together to fight this pandemic as a unified population.

Listen to the scientific experts, not the carnival barkers. Do as these recognized experts advise. Wear your mask and wash your hands! Get the COVID vaccination when it becomes available. Waiting for “natural herd immunity” to occur is dangerous and could result in over 2 million deaths.

And don’t forget the usual, but important, preventive measures, and seek medical help as you would have before the pandemic struck. Your life may depend on it.

Featured image: K.Yas / Shutterstock

Why You Should Get to Know the Folks Next Door

My book In the Neighborhood, published 10 years ago this spring, asked how Americans live as neighbors — and what we lose when the people next door are strangers. These questions are just as timely today. Not only is the country dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic, it is also facing a political crisis. And on top of these global and national issues, there are often painful personal matters, such as the sort of health crisis that my own family recently experienced. In each instance, neighborhoods have a critical role to play in easing adversity and averting disaster.

The inspiration to write my book came from the murder-suicide of a couple — both physicians — who lived on my suburban street in Rochester, New York. One evening the husband came home and shot and killed his wife, and then himself; their children, a boy, 11, and a girl, 12, ran screaming into the night.

What struck me — besides the tragedy — was how little it seemed to affect the neighbors. A family who had lived on our street for seven years had vanished, and yet the impact on the neighborhood seemed slight. No one, I learned, had known the family well. Few of my neighbors, I later learned, knew each other more than casually; many didn’t know even the names of those a door or two away.

Interestingly, many of the happy connections between neighbors occurred in response to natural disasters.

Do I live in a neighborhood, I asked myself, or just in a house on a street surrounded by people whose lives are entirely separate? Why, I wondered, in this age of instant and universal communication — when we can create community anywhere — do we often not know the people who live next door?

To see if I could connect with my neighbors beyond a superficial level, I asked them if I could sleep over at their houses and write about their lives on our street from inside their own homes. Somewhat to my surprise, about half the neighbors I approached said yes.

Getting to know my neighbors in this way enlivened the experience of living there. It helped me forge connections that enriched my life and made it easier for the people on my street to look out for each other.

After I told my story in the book, I heard from people all over the world about how much they missed close neighborhood ties. They also told of more recent times when they’d managed to connect with their neighbors, and how gratifying those experiences had been.

Interestingly, many of the happy connections between neighbors occurred in response to natural disasters. On the West Coast, readers recounted earthquakes and fires; in the South, hurricanes and floods; in the North, massive snowstorms. “When the power went out,” a Florida man wrote me of his neighborhood during Hurricane Andrew, “we began to cook our meals in the street. We enjoyed getting to know each other and learning each other’s stories. After a few days the power came back and we all went back inside. It’s funny, but I find myself looking forward to the next hurricane so we can catch up.”

Today, we’re all living through an unfamiliar kind of natural disaster — the coronavirus pandemic — and I see that neighbors are connecting once again. We’ve read and heard a lot of these stories, so I’ll share just one from my own family.

Just after New Year’s 2020, my 4-year-old granddaughter, my daughter’s child, was diagnosed with a rare form of childhood cancer. Suddenly, her life and the lives of her parents and 2-year-old sister were upended. What had been the happy, busy life of a growing family was now beset by fear, anger, uncertainty, trips at all hours to the hospital, increased medical bills, and two parents trying to work remotely from home.

We’re 11 times more likely to report high levels of confidence in our neighbors than in the federal government, and 5 times more than in our city councils.

My daughter’s family lives in a suburb of Washington, D.C., where the response to their 4-year-old’s health crisis was … nothing. This was not because the neighbors were unkind; it was mostly because my daughter and her husband, after living in their home for nearly four years, knew few, if any, of their neighbors well.

But the COVID-19 pandemic came just three months after my granddaughter’s diagnosis. Suddenly everyone in the neighborhood was living with fear and uncertainty, working remotely from home, and struggling with unknowns including reduced income. On a neighborhood listserv, someone offered to buy groceries and other supplies for anyone especially vulnerable to the virus.

My daughter responded:

Hi neighbors—

Some of you have offered so generously to pick up groceries for those of us who are immunosuppressed. I’m pregnant and one of my children has cancer. If anyone happens to be at a store this week selling toilet paper, tissues, or paper towels, please pick up some extra for us! Happy to pay, of course.

Thank you!

Valerie

The response was swift and strong:

My daughter will deliver items shortly (I’ll wear gloves when I put the items in the bag, so nothing will have been touched by anyone in the house).

Amy

We dropped off some tissue boxes a few mins ago.

Allison & Michael

I have a couple smaller boxes of tissues I’d be happy to drop off to you. Oh and I can give you a container of Clorox wipes too.

Betsy

I just dropped off paper towels and tissues at your front door.

Fran

And that was only the beginning. For weeks, my daughter has been finding bags of groceries and paper goods on her doorstep; in most cases, the neighbors decline payment. “Don’t be silly,” one wrote. “There will surely come a time when I need a favor from a neighbor.”

Today, my granddaughter’s treatments continue and her prognosis is good. Her family’s life is still upended, but now at least they are aided and comforted to know they live among people who know and care about them. Once again, it took a terrible event to bring neighbors together.

Can we find ways to connect with each other without a disaster?

As Americans, we have an independent streak; our impulse for freedom and self-reliance often comes more naturally than the desire for community. Social trends also work against connections. Two-career couples mean fewer people are at home or have the leisure time to interact with neighbors. Larger suburban homes — and the lots they sit on — increase physical distance. Ever-increasing hours of screen time leave us less time to socialize. And the persistent fear we call “stranger danger” steers us away from meeting others — even those who live nearby.

I’m afraid it would be naive to think that — in the absence of a new disaster — we will all just reach out to our neighbors because it’s a nice thing to do.

So, let me offer a different incentive.

Pandemic aside, this country is experiencing a crisis: Politically, we have torn ourselves in half. Whichever side you’re on, half the country thinks you’re not only wrong, but insane.

It’s a crisis that poses a threat greater than any hurricane, fire, earthquake, or pandemic. Left unchecked, I fear it can rip us in two and in the process — regardless of which side prevails — destroy the very protections we rely on for our freedom.

What is the answer? History suggests if we want to begin to repair the social fabric, a good place to start is our own neighborhoods.

Like the meetinghouses and common greens of earlier times, neighborhoods long have been the building blocks of a healthy civil society. Today, they are a place that allows us to get to know, regularly and intimately, people who may think differently than we do. With effort, we can come to know our neighbors beyond a superficial level, to know their challenges and the fullness of their lives. Once we do that, it becomes hard to mark them only with political labels.

For example, there’s a couple that lives near me. Over the years, I’ve seen them work long hours to build their own businesses — he in sales and she in consulting. I’ve come to know the two children they adopted, and for whom they’ve made a loving home. I watched as they remodeled a spare room for her mom to live in when she could no longer live alone. So I’m not inclined to dismiss my neighbors — and certainly not to think them evil or insane — merely because they’ve posted a lawn sign supporting a national candidate with whom I disagree.

“In this age of bitter partisanship and social division,” writes Ryan Streeter, resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, “unity and social healing are not only possible but happening every day when we work with and rely on those who are closest to us.”

In the 2019 Survey on Community and Society, Streeter and colleagues found that most Americans get a stronger sense of community from those they’re close to, including neighbors, than from “their ethnicity or political ideology.” Moreover, they found we’re 11 times more likely to report high levels of confidence in our neighbors than in the federal government, and 5 times more than in our city councils. Seventy-three percent of us say our neighbors can be counted on to do the right thing.

So let’s not wait for the next natural or even man-made disaster to reach out to our neighbors. We have a strong enough motive: healing the bitter partisanship that infects our country.

How to get started? I think it’s just one neighbor at a time. You don’t even have to sleep over. All it takes is making a phone call, sending an email, or ringing a bell.

Peter Lovenheim is a journalist and author of six books. His 2011 book, In the Neighborhood: The Search for Community on an American Street, One Sleepover at a Time, won the First Annual Zócalo Public Square Book Prize. He is Washington correspondent for the Rochester Beacon.

Originally appeared at Zócalo Public Square

This article is featured in the September/October 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock

5 Times That Disease Unexpectedly Changed American History

Very few people foresaw the full impact of COVID-19 in America. And with the president’s recent announcement that he himself has been infected, there is much uncertainty about the repercussions his illness will have on his party, the government, the stock market, and the electorate.

But this is the nature of infectious diseases: the full impact of their arrival, departure, and consequences are rarely foreseen.

This has been seen repeatedly throughout history. During the Civil War, for example, America expected there’d be casualties from soldiers dying in the field of combat. What they didn’t expect was that most would die far from the fighting, as soldiers crowded in camps spread cholera, smallpox, and other infectious disease. More than half of the war dead were victims of disease.

Here are five times major illnesses had unexpected outcomes.

Malaria Fueled the American Slave Trade

Among the earliest European settlers to America were planters who arrived in South Carolina to grow rice. They soon discovered the marshy lowlands where they planted were infested malaria-bearing Anopheles mosquitoes. The disease, which reproduces in red blood cells, proved fatal for white workers in the fields, and planters had trouble maintaining their crops. But they discovered that recently enslaved Africans had a degree of immunity to malaria because of the genetic condition sickle-cell anemia. Rice became a successful crop, followed by cotton, both tended by slaves.

Planters didn’t know what gave the enslaved Africans their ability to endure malaria. They assumed it was because they were genetically hardier. This was far from true; half of all Black children born into American slavery died before reaching the age of five.

Disease Was a Sign of American Success

At the time of the Revolution, Americans enjoyed far better health than their contemporaries in Europe. The average height — a good indication of the state of health — was 68.1 inches, just one inch lower than the average height today (the average European measured 65.76 inches). Roughly 60 percent of children raised in the country survived to age 60. (page 123, “Deadly Truth”)

According to The Deadly Truth: A History of Disease in America by Gerald N. Grob, almost all Americans of the early 1800s resided in the country, leading exceptionally healthy lives. They lived far apart, with little exposure to strangers bearing illnesses; they had healthy diets and a clean environment.

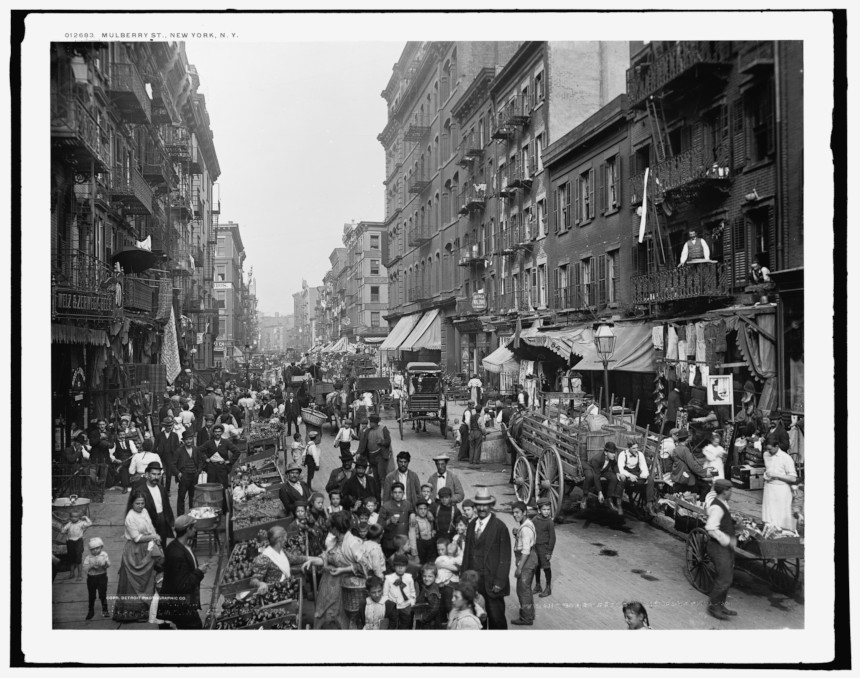

But the population began shifting toward the cities, according to Grob. Between 1800 and 1850, for instance, the population of Philadelphia increased 500 percent, consisting mostly of Americans leaving the country for the city. They were attracted by the commercial possibilities and the opportunity to enrich themselves beyond anything they could realize on a farm.

They came despite the already high risk of contracting a fatal disease in the city. Between 1721 and 1792, Boston was hit by seven epidemics. An outbreak of yellow fever in 1793 killed 1 in 10 Philadelphians.

Urban crowding made disease transmission easier. Water supplies became contaminated. Immigrants, sailors, and visitors brought fresh injections of diseases. Cholera and yellow fever spread rapidly, and cities didn’t have the resources to care for the sick. In big cities like New York and Boston, only 16 percent of children reached their 60th birthday. By 1830, the average male height in America had fallen to under 67 inches.

A Mysterious Illness in Midwestern Livestock Began Emptying Towns

In the 1800s, settlers in the Ohio River Valley noticed livestock sometimes developed a trembling in their legs that soon led to collapse and death. Shortly afterward, their owners showed the same signs, as well as abdominal pains and vomiting. Farmers called it “milk sickness” and believed it was caused by an infectious agent.

The disease proved highly fatal in pioneer settlements, sometimes claiming up to half the residents. Areas of Kentucky and Illinois were especially hard hit. One of its victims was Abraham Lincoln’s mother.

The disease abated as the land became settled and animals began grazing in pasture land instead of the wilderness. It wasn’t until 1923 that Dr. Anna Pierce Hobbs Bixby learned from a Shawnee woman the cause of the sickness. Sheep and cattle were eating snake root, a member of the daisy family, which contains tremetol, a poison so strong it can kill animals and lethally poison its meat and milk. But in the days before it was discovered, the flow of settlers stayed away from areas where milk sickness was reported.

Another Disease Brought Prosperity to Colorado

America’s number-one killer in the 1800s was tuberculosis. Doctors didn’t understand its cause or course, but it seemed to be connected with damp, polluted air. So doctors advised TB patients to move to higher altitudes, where the air was dry and conditions sunny. The recommendation was partly useful. The decreased oxygen levels at high altitudes slowed the growth of the mycobacterium-causing organism. And the sunlight and fresh air was always good for patients.

There were plenty of high altitudes and sunny weather in Colorado. Prior to the 1860s, it had been just another empty stretch of the western wilderness, sparsely peopled by miners and prospectors. But soon a growing number of sanitariums opened in Denver, Boulder, and Colorado Springs, and began to fill with tubercular patients. In time, they made up a third of the state’s population.

Cities grew up around the sanitariums, which attracted caregivers, support staff, and visitors to the patients. And TB patients often helped the town develop, bequeathing money to build streets and schools. In Denver alone, the population rose from 4,700 in 1870 to 106,000 in 1890.

Cleaning Up the Cities had Unintended and Fatal Consequences

Americans were shocked when a polio epidemic struck New England in 1916. For years, the incidence of the viral infections had declined almost to insignificance. Now, suddenly, 9,000 people had contracted the virus and 2,400 died — a fatality rate of 27 percent. The reason for the resurgence was completely unexpected.

Polio is caused by one of four viral strains. In the days before the Salk vaccine, most cases of polio ran their course in a day or two without serious complications. Only one case in 100 produced clinical symptoms, and even fewer caused paralysis. Most people experienced it as a low fever, headache, sore throat, and discomfort. But if the virus attacked the spine or the muscles controlling breathing, the consequences were quick and often fatal.

Up to the 1900s, most children in cities lived in crowded conditions and had been exposed to one of the strains at an early age. Or they gained immunity from maternal antibodies passed on to them as infants. Either way, most children growing up the congested cities were immune.

But as housing became less crowded and cleaner, there were fewer opportunities for exposure. A generation matured with little or no exposure and immunity. Polio swept through these communities quickly, striking down defenseless Americans. Franklin D. Roosevelt is a good illustration. He had grown up in wealth and comfort, and so had no immunity when the virus hit him in 1921 at the age of 39.

Featured image: Ward K, Armory Square Hospital, Washington, D.C., 1864 (Library of Congress)

The Upside of Hypochondria

I have lots of friends who work in the medical field and are exhausted by the extra burden they’re shouldering in these virulent times. Most of the things I do as a pastor are now discouraged — meeting people face to face, visiting hospitals and nursing homes, tending to the sick and shut-in. Electronic interaction is helpful, but it lacks the spiritual and emotional quality of holding someone’s hand. Still, it’s better than nothing, and I’ve found other ways to pass the time, chief among them wondering if I have the coronavirus and how soon I’ll die.

Being a hypochondriac, I have something of a talent for hysteria and regularly (several times a day) remind my wife how tenuous is my grasp on life. Every tickle in the throat, every bead of sweat, every pant for breath is a portent of my agonizing and imminent end. I’ve been a hypochondriac since early childhood, when I discovered the best way to get my parents’ attention was to feign death. I missed an entire month of fifth grade after convincing them I had leprosy, which I had learned about in Sunday school. It turns out that weakness, vision problems, and peripheral numbness are easy to fake. After the first week of acting, I convinced myself I actually had leprosy and sat around for three weeks waiting for my nose to rot off.

I have something of a talent for hysteria and regularly remind my wife how tenuous is my grasp on life.

It’s odd that the best month of my childhood was when I had leprosy. Mr. Evanoff, my teacher, had my classmates make me get-well cards. Jerry Sipes, who hadn’t liked me since I’d reported him to the teacher for peeing on the bathroom floor, wrote in his card that he hoped I died, and Patty Worely, whose dad was a minister, urged me to accept the Lord so I wouldn’t go to hell. She mentioned she was praying for me every day, which I’m certain ended up saving me from the leprosy I quite possibly had. My Grandma Norma sent me a letter with $10 in it, and my dad bought me a box of stale Hostess cupcakes from the Hostess Bakery Outlet in Terre Haute. Twelve cupcakes all to myself, which I think gave me diabetes, so now I’m just waiting for my legs to rot off.

The good thing about hypochondria is its tendency to fill all your waking hours, making other hobbies unnecessary. There isn’t a day that passes that I don’t wonder about the ailments my body is harboring — consumption, dropsy, palsy, and swine flu. I’ve had them all, probably. I fall asleep each night, praying I’ll make it to morning but doubting I will. Unable to sleep (a sure indication of hyperthyroidism), I climb out of bed, walk down the hall to my office, and jot down some notes to my wife regarding my funeral. There are a few people I don’t care for (Jerry Sipes, for instance), who I know don’t care for me, and I don’t want them showing up pretending they liked me. We hypochondriacs can’t stand hypocrisy.

I’ve given years of thought to my funeral. Who’ll give the eulogy? Which songs will be sung? What will they eat at my funeral dinner? What clothes will I wear? Do I go with a suit, wanting to leave a favorable last impression, or should I wear blue jeans and a flannel shirt, reminding my family and friends I was a man of the people? Now with the coronavirus and social distancing, no one will likely attend my funeral, and there goes my chance to watch people’s faces when they see me in the casket and realize I really was sick all these years.

Philip Gulley is a Quaker pastor and author of 22 books, including the Harmony and Hope series featuring Sam Gardner.

This article is featured in the September/October 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock

In Praise of the Slow Movement

It was a long time coming, but the Slow movement has lately picked up momentum in America. Suddenly — too quickly? — it’s a thing.

The coronavirus pandemic is, of course, the explanation. It accelerated a trend that has been simmering for years — the desire to ease back a bit and live more fully in the moment, to seek greater balance, to satisfy the impulse to get in touch with one’s inner tortoise. In other words, to … slow … down.

This year much of the world was jolted into an involuntary disruption of familiar rhythms. It has been a particularly harsh reality in America, where we worship nonstop speed. Fast meals, fast deals, fast cars, fast internet, fast divorces. Don’t dawdle! Race to the finish line.

But ever since the virus crashed our hurry-up lives, we’ve had little choice but to adapt — to be more appreciative of our blessings, more attuned to nature, and, to an extent, slower.

A confession: It was just several months ago that I first stumbled across the Slow movement, even though it’s been around for more than 30 years. It emerged out of what’s popularly called Slow Food, which got its start in Italy. Slow Food gave rise, over time, to Slow Cities, Slow Journalism, Slow Fashion, Slow Sex, Slow Medicine, and Slow Politics. All these Slows emphasize slipping into the natural flow of life, resisting a reflexive break-neck gallop. (Note: You want a more details on Slow Sex? This is not the place, but I’d suggest that the topic is well worth researching. Lots of fascinating material. No need to rush through it.)

You see what I just did there? My detour into sex had the effect of momentarily diverting your attention from the main event — which was intentional. Because one of the tenets of the Slow movement is that meandering yields its own sweet rewards.

I like Slow very much. You’ll never catch me being all show-offy fast. “Pace yourself, Cable. Let’s not be a gazelle,” I hear myself saying daily. Furthermore, I’m not one of those breast-beating multitaskers. More of a minimally effective unitasker.

To be clear, the Slow movement does not ask that we decelerate to a crawl. It only demands that we marinate more completely in our hour-to-hour activities, enriching our lives by savoring what most matters and not trying to impress ourselves (or others) by achieving all our goals in every way every day.

The man who brought the Slow movement to global prominence is Carl Honoré, a journalist whose 2004 book, In Praise of Slow, cast a spotlight on the degrading effects of our too-speedy lifestyles. The Slow movement has no official overseer, but if it did, Honoré would be His Supreme Slowness. Recently, I got him on the phone from his home in London.

“The pandemic is the largest experiment in Slow the world has ever seen,” he said. “It’s a nightmare, but there is a good side to it. People are now more into Slow pursuits like biking, baking bread, sitting around the table with their family.”

He told me that “if there’s been a failing in the American model, it’s the tireless working and commuting. For many, the pandemic is a reminder of what actually matters in life. There’s been a gathering revulsion against the way things were.”

Honoré’s observations carry the weight of authority. Consequently, I am allowing them sufficient time to sink in.

In the last issue, Cable wrote about all-you-can-eat buffets.

This article is featured in the September/October 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock

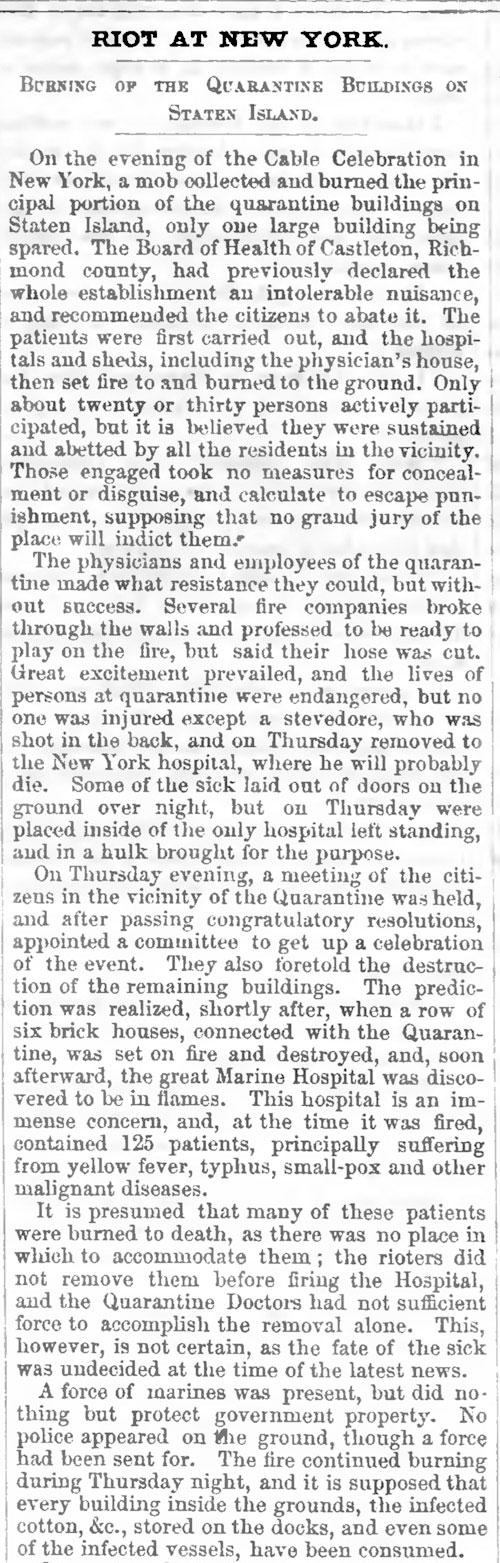

Fear Is Contagious: When New Yorkers Burned Down a Quarantine Hospital

—“Riot at New York,” September 11, 1858

On September 1, a mob collected and burned the principal portion of the quarantine buildings on Staten Island, only one large building being spared. The patients were first carried out, and the hospital and sheds, including the physician’s house, then set fire to and burned to the ground. Those engaged took no measures for concealment or disguise, and calculate to escape punishment, supposing that no grand jury will indict them.

A few days later, a row of six brick houses connected to the hospital was set on fire and destroyed, and soon after, the great Marine Hospital was discovered to be in flames. At the time it contained 125 patients, principally suffering from yellow fever, typhus, smallpox, and other malignant diseases.

Doctors Walser and Bessell have devoted their attentions to the sick, and are administering to their wants, although nearly exhausted from want of sleep and the excitement and exposure resulting from the destruction of the hospital and other buildings. Dr. Walser, throughout the terrible trying scenes of the last 48 hours, has acted the part of a hero and philanthropist.

Three sick men from the ship Liberty are lying on the pier, there being no shelter for them.

The rain is still pouring down, and there is no place within the quarantine walls to shelter the sick.

Featured image: Attack on the Quarantine Establishment, September 1, 1858. (New York Public Library)

This article is featured in the July/August 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Can a Retired Vaccine Company Executive Change How We Think About Pandemics?

As the United States passes another grim milestone with more than 100,000 deaths due to COVID-19, one scientist thinks his idea could have saved lives. And may yet save lives in pandemics to come.

In a small village in France, Dr. David Fedson has been working for the past 16 years to promote a cost-effective strategy of using generic drugs to combat a pandemic.

“If we ran trials on promising drugs before the pandemic and found this approach to treatment didn’t work, well, so what? I was wrong,” Fedson says. “But if, after the pandemic, the research confirms that this approach actually does work, and then we look back at all those people who died unnecessarily, we’re going to feel very bad indeed.”

Drugs such as statins (a cholesterol lowering medication) as well as ARBs and ACEIs (blood pressure medications) are the drug types that he advocates running clinical trials on, as stated in his 2020 medical paper, “Hiding in Plain Sight: An Approach to Treating Patients with Severe COVID-19 Infection,” and other published work. While not averse to vaccines, he sees the mounting death toll as a case in point that to fight a pandemic there needs to be a medical option on “day one,” when the virus first starts spreading.

“The only way to effectively confront a pandemic is to figure out a way to use what we already have,” Fedson says. “Drugs that are generic, inexpensive, and that doctors use every day in their practices.”

Fedson is a retired professor of medicine from the University of Virginia who also served as the medical director at Aventis Pasteur, a European vaccine company. He saw the weakness of a vaccine-only approach to an influenza pandemic back in 2001 when he was instrumental in establishing the Influenza Vaccine Supply International Task Force.

“The whole purpose of the task force was to get the companies we worked for — and the top-tier executives running them — to pay attention to the fact that someday we would have an influenza pandemic,” Fedson says. “And it became quite apparent to me that the global capacity to manufacture pandemic vaccines just wasn’t there. By the time the vaccines would become available, it would be too late.”

Dr. Alice Huang, a virologist and former Harvard Medical School professor who was involved in developing a vaccine for HIV, confirms that an approved vaccine for the coronavirus will take time.

“We all really need something sooner rather than later, but in my experience with making a vaccine…it takes a long, long time,” Huang says. “And when you read about people saying that it would take about a year to 18 months, that is if everything goes perfectly right.”

Fedson recounted an early career experience treating cholera patients in India, not by targeting the pathogen, but focusing on keeping the patients alive long enough so they could overcome the worst effects of the disease.

“I spent three months on the Johns Hopkins Cholera Unit in Calcutta as the team fine-tuned a formula to rehydrate cholera patients, a breakthrough that has saved tens of thousands of people ever since,” Fedson says.

What made it effective is that the rehydration treatment could be lifesaving not just for cholera patients, but also for those suffering from severe diarrhea caused by other diseases. Regardless of what brought on the severe diarrhea — it could be a virus, shigellosis, or any number of other infections — the same treatment would keep the patients alive long enough until their own defenses took over and the diarrhea stopped.

The same concept of focusing on the well-being of the host instead of defeating the pathogen may be applied to treating COVID-19 as well.

In the case of COVID-19, when the immune system becomes compromised, its response can be too strong, causing a self-destructive form of inflammation that has been dubbed the “cytokine storm.”

Cytokines are small chemical messengers that tell the immune cells of the body to become activated, so they are ready to fight the virus. As is increasingly evident in some COVID patients, when that inflammation occurs in the alveoli of the lungs — the air sacs critical for delivering oxygen throughout the body — it can cause acute respiratory distress (ARD) and death.

Dr. Brian Ward, a professor at the Centre for the Study of Host Resistance at McGill University, who specializes in immune system response, says that a virus usually does not kill its host, but that COVID-19 is behaving atypically.

“It’s a weird virus; it’s not like many of the other viruses that we deal with,” Ward says. “Even though we’re closing in on one and three-quarter million people infected in the U.S. and five and one-quarter million worldwide, we do not yet have a clear idea of why some people seem to walk through the illness and other people get into real trouble really fast. And certainly, the idea of the body’s reaction, the so-called cytokine storm theory, is one of the hypotheses for that late inflammatory reaction in the lungs.”

Worldwide, there are currently more than 337,000 confirmed fatalities due to COVID-19 according to the World Health Organization’s May 24, 2020 coronavirus situation report, with the numbers likely to rise.

Instead of making the virus the primary target, which is what vaccines and antivirals do, Fedson says the top priority is to find a cost-effective generic drug — or a cocktail of drugs — that will reduce some of the worst consequences of the immune system’s overly zealous response to the virus and save lives.

“We’re talking about a way of treating people with acute critical illness due to any cause, and it can be a pneumonia, ARDs, it can be bacterial sepsis, it can be viral diseases, it can be lots of things that cause people to be hospitalized and get into ICUs,” he says. “The wonder and the beauty of it is that we’re using generic drugs that are available to people in Bangladesh, just as they are available to people in Boston.”

In the midst of the pandemic, Fedson’s idea may finally be gaining traction. Investigators at numerous U.S. universities — as well as in several countries outside the U.S. — have undertaken trials of angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), a kind of cardiac medication that Fedson says might be especially effective when “repurposed” for use in pandemic illness. ACEIs and statins are being studied as well.

Two of the most important and innovative of these trials on ARBs are now underway with COVID-19 patients at the University of Minnesota trialing the blood pressure medication Losartan. As an ARB, Losartan blocks activity on a receptor site that raises blood pressure. It is possible that blocking this receptor will also diminish inflammation and reduce damage to the lungs of COVID patients.

“Losartan has an established safety profile and is readily available,” says Dr. Chris Tignanelli, an assistant professor at the University of Minnesota Medical School overseeing the trials and administering the drug to both in-patients and out-patients. “We wanted to test a readily available, cheap, FDA-approved generic drug with potential efficacy against COVID-19.”

Tignanelli was initially swayed by promising reports written by doctors in China who observed “a one-third reduction in lung injury” in SARS-infected lab mice who were given Losartan. The current trials are financed in part by the COVID-19 Therapeutics Accelerator Funds — a Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation initiative.

Dr. Michael Puskarich, the other doctor running the University of Minnesota’s randomized control trials, also sees potential for Losartan.

“Losartan is different from the other treatments being tested right now — it’s not an antiviral medication,” Puskarich says. “We’re trying to prevent the lung injury caused by the virus that makes it so deadly. We’re trying to turn COVID-19 into an everyday coronavirus, the common cold.”

The cost for a typical regimen of Losartan (14 tablets) is $15. Tignanelli says Losartan most likely will not be a “miracle drug,” but could be used as part of a cocktail of drugs.

“The story probably won’t end with Losartan,” he adds. “I doubt that any single drug is going to be a magic bullet as we’re probably going to need some combination of anti-inflammatory drugs targeting different parts of the immune pathway.”

Drug cocktails are something that hospitals such as St. Luke’s University Health Network in Pennsylvania are administering to their COVID-19 patients. At St. Luke’s, doctors have used a combination of vitamin C, zinc, atorvastatin, and steroids, as well as high-flow nasal oxygen and other pioneering approaches.

“Of course, the concept of using cheap drugs makes perfect sense, even to a random person on the street,” Fedson says, recounting a woman he met on a bus pre-pandemic who agreed it was worth a shot. “Unfortunately, she is not the president of the United States, and she’s not the director of the NIH [National Institutes of Health], or the director of the CDC [Centers for Disease Control], or the director-general of the WHO [World Health Organization]. I wish she were. If she had been, we would be much better off today than we are.”

Featured image: Shutterstock

Funeral Service in the Time of COVID-19

On a chilly and rainy day in late April, I stood at a grave in Queens County, New York, with three mourners in protective masks, preparing to lead the graveside prayers. The casket had already been lowered, unlike how it has always been done, and it hit me that I would be praying to a hole.

The family members, who had come from Long Island to bury a 97-year-old grandmother, seemed to come to the same realization. They peered down uncomfortably into the grave, at the steel vault that covered the casket. There had been no church service or wake. And, now, they could not even be close to the casket that held their loved one’s remains.

I felt responsible, as if I were the one letting them down. But my discomfort at being unable to serve people properly was a fleeting bad moment in three draining months that have taken their toll on people like me who make their living as funeral directors. The deaths keep coming. And we keep doing our jobs. Unlike our fellow citizens, who can look away and find escape in not confronting the reality, we cannot.

As I spoke to other funeral directors in New York about what they have been going through, the same themes emerged time and time again: trying to cope as the wave of death overwhelmed us, finding a renewed sense of duty to the dead as families were kept away, fighting impossible odds to keep bodies from going unattended or shipped off to a potter’s field.

In the months preceding the U.S. outbreak, we all had watched the news of the pandemic as it played out in China and Italy. We were curious about how these countries were dealing with their dead. Perhaps it was a mix of wishful thinking and naivete that made us think, “That could never happen here.” Until it did, thrusting us into death overload by early April.

Funeral homes in the five boroughs of New York quickly became filled to capacity. As the pandemic gripped the city, the death toll in New York City reached almost 20,000 and funeral homes were forced to turn away scores of frantic families looking to bury their dead. They had neither the staff, nor capacity, to handle the surge of deaths. The city was prepared to send remains to New York City’s own potter’s field, on an island in the East River. The city order was later rescinded, but it only fueled our ever-present sense of urgency.

We all came to share grim accounts of what death had become in New York.

In Brooklyn, as a funeral home van made its way down a city street, residents called out to the driver from the sidewalks. “People were trying to flag it down because they have dead bodies in the house and the medical examiner’s not answering the phone,” Tom Libraro wrote on his Facebook page. “It just showed the desperation of people when the morgue attendants couldn’t handle it,” said Libraro, who works at Brooklyn Funeral Home & Cremation Service.

Anthony Cassieri, who owns Brooklyn Funeral Home & Cremation Service, usually handles about 450 funerals in a year. In the past month alone he has done 149.

“We couldn’t get the bodies embalmed fast enough for the people who were having viewings. There was no outlet for crematories. And we didn’t have the space to keep people.

“I had to close down for ten days to regroup,” says Cassieri. He didn’t want to be rendered as little more than a “body disposer.”

“We were still taking calls and talking to people,” he says. “Some were begging for help, telling us that they’d called 21 funeral homes, but no one could help us.”

“It’s not that we don’t want to help you. We can’t,” he and his staff told callers.

To store the bodies, Cassieri rented a refrigerated truck. Those trucks became an arresting sight outside funeral homes and hospitals around New York. Then came the discovery of 100 bodies decomposing in an unrefrigerated truck at another Brooklyn funeral home. Afterwards, the NYPD came knocking on the door of Cassieri’s business, insisting on inspecting his truck to ensure that it was refrigerated.

Cassieri presses on. He regularly begins work at 5:30 a.m. and doesn’t leave until well after midnight. In one day alone, Cassieri made 11 hospital removals.

“We’re doing our best. There are just not enough hours. We can’t move or prepare bodies fast enough. We’re locked down by cemeteries and crematories. There’s only so much we can do,” says Cassieri, who purchased additional stretchers and a new removal van. He rented a U-Haul truck to make extra removals.

It’s hard not to feel abandoned by the government. “Nobody helped us. FEMA never stepped in, and the city never called and said we could move bodies 24 hours a day from the medical examiner’s,” Cassieri says.

In our business, we, just like the families of the deceased, have relied on the comforting and predictable rituals of funeral services. No more. They have been replaced by chaos and uncertainty. There are no typical days. We adapt as best we can to rules and regulations that seem to change arbitrarily, and often without notice. Sometimes those rules seem borne of fear rather than neccesity.

At the same, we can’t help but feel a special duty as we serve as often lone witnesses at funerals that are unattended.

“Today, my daughter and I live-streamed three graveside services via Tribucast,” says Peter D’Arienzo, Market Director of Dignity Memorial, Long Island. “At two of these services, the rabbi and monsoon rains were the only ones there.” Through technology, D’Arienzo was able to bring in more than 100 guests from Israel, Germany, France, and around the U.S. “Our mission, and why we chose funeral service, is to give families under any conditions, anyway that we can, a chance to say goodbye,” D’Arienzo wrote on Facebook in mid-April.

As the number of deaths mounted, D’Arienzo’s daughter, Sophia, offered to assist. She was a nursing student, home from college. “Sophia was better at it than I was,” he says. She assisted for two weeks. Others had to fill in when D’Arienzo was forced to self-quarantine for two weeks. Dignity Memorial has live streamed over 25 services to ten foreign countries, and 35 states, with over 1,200 links opened during the COVID-19 pandemic.

They kept going even as rain swept through the area. “The most powerful services are when it is just me and the rabbi at the graveside,” D’Arienzo says.

It is a time when nothing seems easy or predictable for any of us charged with attending to the dead. At one of Cassieri’s funerals, elderly family members had rented a limousine to travel to a New Jersey cemetery. When they arrived, the cemetery refused to allow the car inside the gate. Only one person was allowed at the gravesite, Cassieri was told. “We didn’t know that. That was something that changed between us ordering the grave and getting there,” he says. The cemetery eventually relented, but allowed only one family member to get out of the car and stand by the grave. The family was left to decide who that would be.

The rules change almost hour to hour. Thomas Will, a funeral director for 50 years, was told by a cemetery in the Bronx that no more than five people could be in attendance, all of them required to wear masks and rubber gloves. But when he arrived at the cemetery with two cars bringing family members, he was told that the family would have to remain in their cars.

“You mean to tell me the priest is going to do the service and the family is going to be on the road and they can’t exit their vehicles?” he asked the cemetery official.

He went back to the family. “There’s no way that I’m going to sit in the car during my mother’s service,” said one of the daughters. She threatened to call the police. After the priest arrived, he and Will spoke with the foreman. A compromise was reached. The casket was taken out of the hearse and wheeled to the roadside. The family was able to stand outside of their cars as the priest conducted the brief committal service.

At times, New York has had to look elsewhere for help burying its dead. In the early days of the crisis, John Scalia, owner of the John Vincent Scalia Home for Funerals on Staten Island, located three crematories in Pennsylvania. In April, he would be asked to do 90 cremations, many times the normal rate, but the outreach to Pennsylvania made a difference. “We were able to keep people out of the trailers,” he says. Scalia also made it his mission to handle funerals free of charge for indigent COVID-19 victims.

“I think it’s our obligation to take care of these people. We’re in the funeral business,” says Scalia.

I have spent four decades as a funeral director. In that time I thought I’d seen just about every imaginable way of dying. But nothing could have prepared any of us for this. The days have been dark, filled with fear, frustration, and uncertainty, as we’ve had to face our most daunting challenge as funeral directors. Many of us wonder if we have fallen short of the oath we took, when we were licensed, not to violate our obligation to society or to the dignity of our profession. Maybe, as one of my colleagues said, “It takes this to remind us why we do what we do.”

Featured image: Sophia D’Arienzo live streams a funeral service at which Rabbi Ronnie Kehati officiates (Photo Courtesy of Peter D’Arienzo)

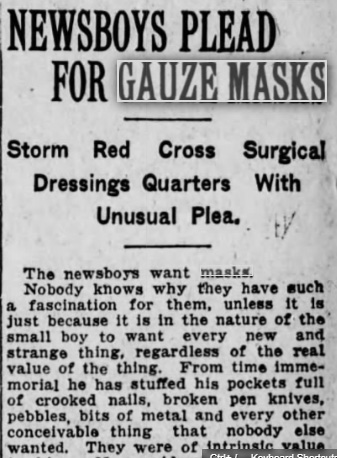

The Mask Slackers of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic

The orders from many governors and mayors during the current COVID-19 pandemic have been similar: stay at home, leave only for essential trips, no gatherings. The toll of stay-at-home orders on businesses has been severe, sparking small and large protests around the country to open these states and municipalities back up, invoking the infringement on people’s individual liberties.

The last pandemic of similar proportions, the Influenza pandemic of 1918, triggered a comparable patchwork of ordinances and ensuing economic fallout. Some Americans’ reactions a century ago took similar form, particularly a group of fed up San Franciscans who called themselves the “Anti-Mask League.” Although San Francisco saw one of the worst U.S. outbreaks of the pandemic, these dissidents opposed orders from the city’s Board of Health not because of the economic implications, but because they saw it as their right to walk the city maskless. Besides, they didn’t think the things were working anyway.

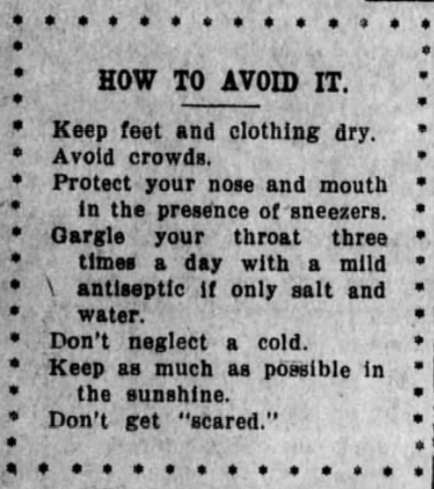

By September of 1918, it was clear that “Spanish influenza” was a serious virus with enormously destructive potential in the U.S. A press release in newspapers on September 25th warned readers to “Avoid crowds” and “Protect your nose and mouth” as well as less explicitly heedable advice like “Keep as much in the sunshine as possible” and “Don’t get ‘scared.’” The message to the public echoed the patriotic tone cultivated during the war: “Only by loyal and intelligent co-operation of the general public can the epidemic of Spanish influenza be prevented from spreading thruout the country and hampering our war work. Do your bit” (J.H. Duckworth). Dr. Gordon Henry Hirschberg made a significant request of Americans a few weeks later that was printed prolifically: “Kissing is another prolific method of infection, and this practice should be stopped except in cases where it is absolutely indispensable to happiness. Kissing between members of the gentle sex can certainly be abolished without hardship.”

The importance of gauze masks in the anti-flu effort, especially for medical workers, was considered paramount. Leading the effort was the American Red Cross. The organization had grown from a little more than 100 local chapters at the beginning of World War I to almost 4,000 by its end. In October of 1918, the U.S. Surgeon General requested that the American Red Cross “assume charge of supplying all the needed nursing personnel and furnish emergency supplies.” The ARC mobilized nurses and mask-makers across the country, compelling women to get to work sewing gauze masks.

That month, cities began enforcing mask requirements. In Canada, railway passengers were refused admittance without masks. Iron River, Wisconsin — having experienced a bad outbreak — required mask-wearing in public. Tucson and San Diego passed ordinances mandating mask-wearing for store workers, and other cities did the same for barbers and nurses.

On October 17th, San Francisco closed churches, schools, theaters, “cabarets, and merry-go-rounds” to slow the spread of the virus. The city’s Board of Health, led by Dr. William C. Hassler, instituted a mask ordinance. The fine for disobedience was five dollars, which was then given to the Red Cross. Although several cities in California had such ordinances, the rule was never enforced statewide. In San Francisco, 100 people were arrested in October — reported in the news as “mask slackers” — and nine of them were sent to jail. In Stockton, California, one policeman apparently found his own father to be a mask slacker, and he arrested him, according to the Sacramento Bee.

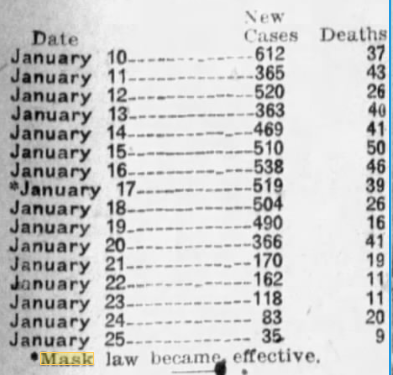

Hassler assured his city that if everyone complied with the tight restrictions they would soon see influenza cases decline, after which they could go about business as usual. Oddly, the Health Officer also reportedly endorsed a massive sing-along in Golden Gate Park in mid-November, saying that as long as everyone wore their masks, it would “be in the nature of an experiment to see what effect music has on the influenza bacillus.” Hassler was also caught without a mask at a boxing match a few days later, maintaining that he must have moved it to smoke a cigar when the photo was snapped. Still, throughout November, San Francisco saw days with zero new cases of the disease, and, on November 21st, they unmasked at noon. Hassler declared the epidemic to be over.

In December, however, cases in San Francisco started to creep back up, and Hassler called for everyone to mask up again. The Board of Supervisors voted against reinstating his ordinance though, on December 19th, one arguing that it was unfair “to the businessmen of San Francisco.” The meeting was described in the Sacramento Bee next to a public service announcement declaring “Spanish Influenza More Deadly than War.”

Going into 1919, cases in San Francisco continued to rise. On January 17th, the Board of Supervisors gave in to Hassler’s request, putting the mask requirement back into place. At that meeting, a San Franciscan announced she had organized an Anti-Mask League whose purpose was to “oppose by lawful means the compulsory wearing of masks.”

The Anti-Mask League met that weekend and declared themselves “Sanitary Spartacans.” They claimed the masks were useless and demanded the mayor repeal the ordinance requiring them. The group was led by a Board member and several doctors. The next week they held a meeting at Dreamland Rink, and 2,000 people showed up. They read bulletins from the State Board of Health “showing compulsory mask-wearing to be a failure” and urged attendees to “not submit to the domination of a few politicians and political doctors.” Simultaneously, the number of new cases in San Francisco was dropping each day since the second mask ordinance had been implemented. The League attended a Board meeting and hissed at supporters of the ordinance.

San Franciscans wrote into the Chronicle’s “People’s Safety Valve” section, deriding the ordinance and moaning that “the muzzle is a farce and an outrage against our liberties.” One man claimed his short beard was “the best kind of a mask, as it not only keeps the bronchial tubes in good condition, but it is better than any gauze mask for catching microbes.”

People complained that the Board ought to dedicate itself to cleaning up the city instead of implementing “autocratic” rules. The vocal opposers to the mask ordinance couldn’t believe that nine out of ten San Franciscans supported it, as was reported, since they claimed many people on the streets weren’t wearing them. The Chronicle even questioned the efficacy of face masks in an article, positing that more data would make clearer whether or not they were working.

San Francisco’s numbers continued to drop, though, and come February, the “gauze law” was scrapped. The Anti-Mask League presumably disbanded, having no more measures to oppose. People were free to roam the streets maskless without worrying about fines or arrest, and Hassler touted his rule for creating a 1000 percent decrease in cases over 11 days. Once again, he declared the end of the epidemic in San Francisco.

Featured image: Theater advertisement in the Sacramento Bee, January 1919

9 Unique Activities to Keep Boredom at Bay During Quarantine

COVID-19 has forced us to remain inside, where it’s all too easy for boredom to take hold. Instead, try one of these unique activities that are perfect during this time of social distancing.

9. Parody Famous Paintings

Who knew that recreating artworks in lockdown would become the hottest social media trend of 2020? https://t.co/F0X9icY2dF pic.twitter.com/RWmtoaW5gb

— Artnet (@artnet) May 4, 2020

You have probably seen this one already, and participating is simple: find a painting online and use items around your house to replicate the outfits, setting, and props within the painting. Since this activity is designed for fun, the details do not have to be exact. Put your own unique spin on the artist’s work. When your painting is complete, take a picture and put it side-by-side with the original so you can share your creativity with others.

8. Find Inanimate Faces

What inanimate object face are you on this the 467th day of lockdown? I think I am in a perpetual state of number 6 pic.twitter.com/alyfOfGrRi

— James (@Shabby_Dad) March 31, 2020

You may have never noticed it, but faces can be spotted amongst many household items. For instance, the pillows on your couch might form eyes, or the cord on your chandelier possibly creates a long nose. This activity taps into your imagination and will send you on a scavenger hunt throughout your entire house. More than likely, you won’t look at any of those objects the same way again.

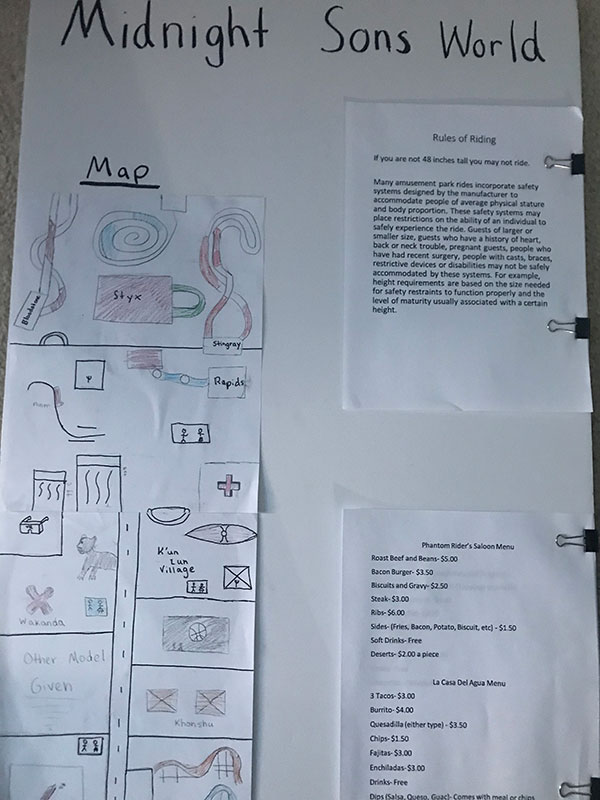

7. Design an Amusement Park

If you are a parent, this activity is a great way to keep your kids occupied, but it’s also fun for adults. Designing an amusement park allows people to see what it would be like to be an Imagineer at Disney theme parks or a Universal Creative team member. In this venture, you’ll come up with the name of an all new theme park, as well as its location, attractions, rides, and restaurants. What makes your park unique? What characters can you meet throughout? Does the park have a gift shop? How much does your park cost? There are endless ways to execute this project. Here’s one lesson plan to get you started.

6. Play Balloon Spikeball

Spikeball is an exciting outdoor game where players bounce a medium-sized ball off a net in an attempt to score points against other players. But Spikeball can be adapted to work indoors as well; just replace the ball with a balloon. One tip: bring a few extra balloons, in case somebody gets carried away.

5. Dress Up with Your Family

Best Family Costumes😂 pic.twitter.com/hUoCTYkOTp

— ZuZuQ🌹9️⃣ (@ZuZuQ5) May 4, 2020

People — sometimes entire families — are dressing up each day in accordance with a daily theme, sometimes oriented around a holiday, a color, a movie — any topic will do. Another adaptation is where each person chooses what another family member wears to dinner. Just put the names of everyone in a cup and draw to see who designs whose outfit. Like other items on this list, this activity is open to interpretation and can be changed to fit your group’s unique ideas and interests.

4. Go on a Scavenger Hunt

Scavenger hunts are a classic. Find some unique or unusual items, then hide them around the interior and possibly the exterior of your house. See who can find the most items. Put a prize on the line, or just play for fun. It is like an Easter egg hunt, but with more variety. Check out these ideas for adults and children.

3. Create a Harry Potter Escape Room

Use your knowledge of the Harry Potter series to create an immersive experience for your friends or family, whether in an escape room format (find and solve clues to escape the room) or an Amazing Race format (go to different locations throughout your home and complete challenges, getting clues in order to reach the finish line). Either way, incorporate different things from the books, like the magical creatures, Deathly Hallows, Hogwarts classes, or whatever else you desire. This example from Peters Township Public Library can provide inspiration. This same activity can also be completed with a plethora of other books and movies.

2. Try Your Hand at Trivia

Pick a collection of categories and design the questions and answer choices to go along with it. There are multiple ways to do this. Kahoot, Quizziz, and Gimkit are great for creating trivia games. You can also draw a Jeopardy board or pull random questions out of a hat. You can even set up a video conference to play with socially distanced friends and relatives.

1. Film “A Day in the Life” Videos

With so many entertaining options for quarantine, you need a way to remember them. Film yourself and those around you participating in their quarantine activities. Are your parents cooking a new dish? Film it. Going on a scavenger hunt? Film it. Building a puzzle? Film it, but maybe time lapse is better for that one. You can edit the videos together and have your own documentary to commemorate quarantine.

Featured image: Shutterstock.

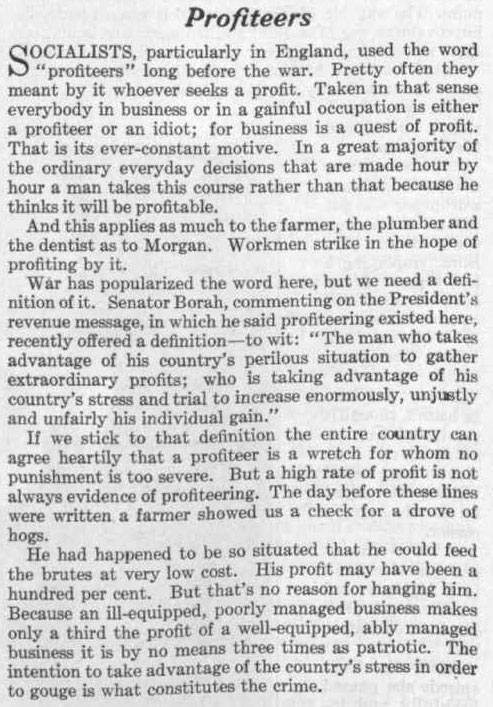

Pandemics, Profits, and Price Gouging

The first case of coronavirus in America was reported in January 2020. The first death occurred the next month. But for many Americans, the pandemic only got real when the toilet paper disappeared from store shelves. We understand shortages. And we know they’re usually accompanied by higher prices. In the past month, consumers in several states have reported sharp price hikes for masks, hand sanitizer, disinfectant wipes, and other necessities.

A store in Philadelphia doubled the price of a pack of face masks to $50. On Amazon, a Florida man offered fifteen N95 face masks for $3,799. Texas state officials have received over 4,000 price-gouging complaints during the pandemic emergency.

Natural disasters always create opportunities to sell necessities at exorbitant prices. As long ago as 1666, merchants raised the price of fish 300 percent in the days following the great London fire. Following the San Francisco earthquake of 1906, the price of bread jumped from a nickel a loaf to a dollar. The price of ferry rides out of the city were jacked up to the 2020 equivalent of $1,500. The price to hire a wagon to move possessions out of the city jumped from $5 to $100.

More recently, after Hurricane Katrina, Mississippi officials received roughly 1,400 complaints a day about price gouging. After 2017’s Hurricane Harvey, some stores were selling cases of water for $99. Hotel owners tripled or quadrupled their room rates.

Business owners who sell vital supplies in an emergency deserve to make a profit. But when is it too much profit?

In 1918, a Post editorial differentiated between business owners making a profit and a profiteer “who takes advantage of his country’s perilous situation to gather extraordinary profits.” A profiteer uses his country’s stress and trial “to increase enormously, unjustly and unfairly his individual gain.” The editors concluded that “The intention to take advantage of the country’s stress in order to gouge is what constitutes the crime.”

But an article from the March 5, 1921, issue of the Post put some of the blame for price gouging on consumers’ irrational behavior: “No prices were too high for the things that we felt we had to have at once… Having worked hand in glove with the speculator and profiteer to inflate prices by demanding goods in excess of needs, it does us little good now to denounce profiteering.”

While few consumers need a dozen mega-packs of toilet paper, the question remains: Should anything be done about price gouging and profiteering, and if so, who should do it?

No federal laws prohibit the practice, though the Justice Department is asking Americans to report pandemic-related scams or frauds to the Disaster Fraud Hotline.

However, 44 states enforce laws against this form of profiteering. Some states allow businesses to raise prices temporarily from 10–30 percent in response to shortages and hoarding. Other states, though, practice zero tolerance for hiking prices in emergencies.

A group of 33 state attorneys general notified Amazon, Walmart, eBay, Facebook and Craigslist they must do a better job in removing “unconscionably priced critical supplies.” They wrote, “We believe you have an ethical obligation and duty to help your fellow citizens in this time of need by doing everything in your power to stop price gouging in real-time.”

However, business owners may disagree on what ethics oblige them to do. Some retailers and economists claim it actually serves several purposes, including signaling manufacturers and suppliers to increase production and distribution and helping ensure essential goods go where they are most needed. For example, if a drug store continues to sell face masks at their usual retail price, hoarders and panic-buyers could quickly clean them out. None would be left for later shoppers. By raising the price to a deterring level, merchants can continue to ensure needed products will remain available.

Another option is rationing, which might work, economists say, but it usually takes too long to set up a workable system. And government price controls would be defied by business owners.

Consumers, however, may not see the advantages of price gouging. They may only see businesses raising their prices because buyers have no option in an emergency. Yet grocery stores that held toilet paper to its usual retail price saw hoarders buying as much as they could fit into a shopping cart. Which is exactly the situation that “price gouging” is meant to prevent.

Featured image: Shutterstock

America: 200 Years of Responding to Epidemics

To try and get a perspective on the current pandemic, many have compared it to the 1918-19 “Spanish flu” (which was actually an “American flu,” since it began in Kansas). While it was extraordinarily deadly, it wasn’t the only epidemic that has struck our country. But as Americans got smarter about controlling contagion, their epidemics became less deadly.

The first epidemic in the Americas was caused by smallpox, brought by European explorers and settlers. There are no numbers on the fatalities caused by this contagion, to which indigenous people had no resistance, but one estimate claims 80 percent of all native Americans were killed. Entire tribes vanished after contact with the new disease.

Colonial America knew the destructiveness of epidemics. In the 1660s, the bubonic plague had broken out in London, killing 100,000. To prevent a similar outbreak, Americans followed the European example of closing ports and quarantining ships in harbors until any contagious disease aboard would have died off.

When a ship left a port, its captain was usually furnished with a document called a bill of health. A ‘clean bill of health’ signified that the port from which the vessel sailed was free from infectious disease. A ‘touched’ bill indicates that there was a suspicion that disease was present, and a ‘foul’ bill shows that disease was raging in the port.

Ships without a clean bill of health had to lay at anchor in the harbor for up to 40 days, and no passengers or cargo were unloaded. No one is quite certain why the number 40 was chosen, but it was originally used by Venetians during the days of the Black Death. (From the Italian quaranta giorni comes “quarantine”.)

Even with precautions, epidemics entered America from its port cities.

In 1793, a group of 2,000 refugees fleeing the slave revolt in Haiti gathered at the port of Philadelphia. Somehow the bill-of-health system failed. Some passengers were already sick with yellow fever, and the ships had inadvertently brought infected mosquitoes — the source of the illness —in their holds.

The city responded to the illness by isolating the refugees and their belongings. But it was too late; the fever had already escaped into the city.

Philadelphia was then the nation’s capital, and when government officials saw the rising death toll, they took the hint and left the city. Those who remained tried to follow doctors’ advice to avoid contact with sick, and even each other. They also resorted to folk remedies. Men, women and children would smoke cigars constantly, believing this would ward off the “bad air” that carried the pestilence. Some Philadelphians had themselves bled — the presumed cure for almost everything in those days. They chewed garlic, or put it in their shoes. When outside they covered their noses and mouths with handkerchiefs soaked with vinegar or camphor. And they burned gunpowder, believing this would improve the oxygen in the atmosphere.

A Philadelphia publisher described the empty boulevards of the stricken city.

The coffee-house was shut up, as was the city library, and most of the public offices. Many never walked on the sidewalk, but went into the middle of the streets, to avoid being infected in passing houses wherein people had died.

Acquaintances and friends avoided each other in the streets, and only signified their regard by a cold nod. The old custom of shaking hands fell into such general disuse that many shrunk back with affright at even the offer of the hand. A person with any appearance of mourning was shunned like a viper. And many valued themselves highly on the skill with which they got windward of every person whom they met.

Over 5,000 Philadelphians died in this epidemic, nearly 20 percent of the city’s population.

In 1832, a new contagion arrived in America: cholera. Ports were still quarantining any ship without a clean bill of health, but the lessons of past epidemics were being forgotten. Impatient passengers jumped ship or bribed the crew to put them ashore before the quarantine expired.

The Post reported incidents like these. From The June 28, 1823 issue, they noted the person who violated the quarantine law by escaping from the British sloop, Athol, “was a Mr. Humphreys, a passenger from the West Indies, belonging to Philadelphia. He was apprehended on Saturday last, and after an examination, during which he was quite fractious, has been sent down to the quarantine ground in custody.”

An item from the July 8, 1826, issue relayed, “A man about 30 years old was found on the shore near New Utrecht, New York, in a dying state. It was ascertained that he had been landed from on board a vessel arrived from Savannah, then lying at quarantine. As he died almost immediately after being discovered, the captain of the vessel was arrested.”

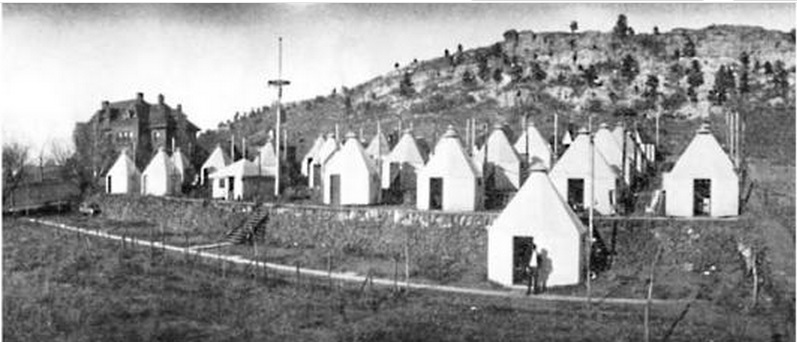

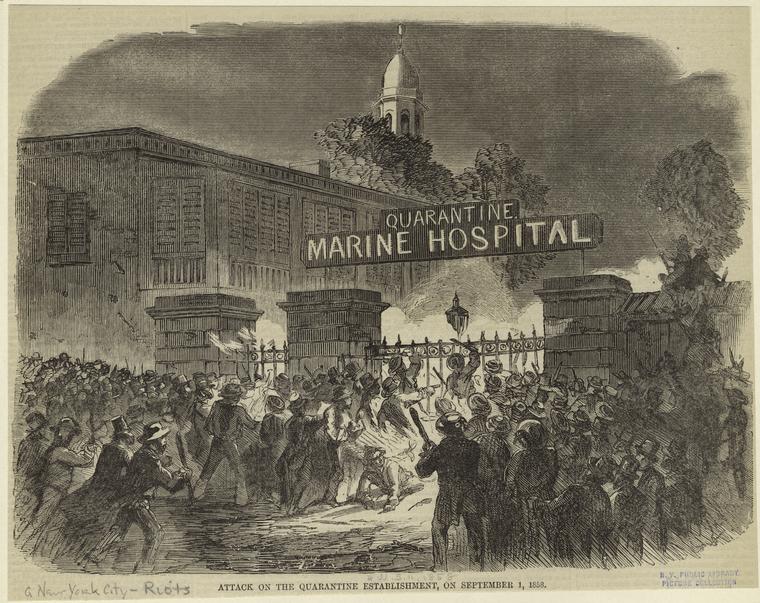

Many ports now disembarked passengers and isolated them in quarantine hospitals, nicknamed “pest houses.” One of America’s largest quarantine hospitals was located in New York harbor, on Staten Island. Residents of the island were unhappy that powerful contagions were contained close to their homes. In 1858, the islanders set fire to one of the hospital wards. On September 11, the Post reported its patients were hastily taken outside. “Some of the ill laid out of doors on the ground overnight, but on Thursday were placed inside of the only hospital left standing.”

The next night, the locals returned to burn down the remaining buildings, including the main hospital building. “At the time it was fired,” reported the Post, “it contained 125 patients, principally suffering from yellow fever, typhus, small-pox and other malignant diseases. It is presumed that many of these patients were burned to death.”

Eight years after the burning of the hospital, New York’s continued cruel treatment of epidemic victims prompted the Post editors to comment on the city’s harsh new law against cruelty to animals. They wrote in the May 19, 1866, issue, “What the New Yorkers need next is a law against cruelty to poor, sick, and dying humans — see N.Y. papers’ reports on quarantine doings.”

In 1878, an epidemic of yellow fever hit southern states. Memphis, TN, was struck particularly hard. Any resident in good health was advised to leave the city and head into the country. But residents in infected districts were forced to remain at home by mounted guards.

A doctor who’d seen yellow fever outbreaks around the world told the Post:

He has seen nothing to compare with the death-stricken aspect of Memphis at the present time. The wealthy have almost all departed, leaving the poor to shift as they may for themselves, and to the horrors of the plague are added those of a condition approaching to famine.

The banks are open only one hour a day. At night the streets are lit up with here and there the gleam of death fires, which burn in front of houses containing a corpse though not of every such house, for many a victim dies alone after suffering unattended, and there is no one to put out the customary signal. Persons taken sick on the streets crawl into unoccupied tenements and their corpses are afterwards discovered by the odor. The peculiar smell can be discerned at a distance of three miles.

By the next great epidemic, an outbreak of typhoid fever in 1906, medical science had a good idea of how the causative agent was being spread. Knowing the danger of contaminated water, New York had already begun building a modern sanitation system. But slow construction led to widespread typhoid infection, killing over 20,000 people.

1918 was the year of the great flu pandemic. The H1N1 virus swept around the world, infecting an estimated 500 million people — one third of all the people on earth. America suffered less than many countries because of precautions such as social distancing and face masks. Many public activities were postponed for months. Even with these measures, the flu killed an estimated 675,000 Americans. If America suffered a proportionally similar loss with today’s population, the death toll would be over two million.

The 1918 pandemic was something of a turning point. Up to that time, epidemics had usually caught America ill prepared. But with modern medicine and hygiene, epidemics lost much of their lethal power.

An epidemic of diphtheria occurred in the early 1920s and was responsible for 15,000 deaths. But an effective vaccine, developed in 1923, has brought the incidence of diphtheria so low, just two cases were reported between 2004 and 2017.

In 1942, America saw the incidence of polio climb to epidemic scope as the annual infection rate rose from 4,000 to 57,000 in ten years, with 3,145 deaths. But the incidence dropped sharply after the introduction of Dr. Salk’s vaccine in 1955. Now the CDC reports that America has been polio free since 1979.

And HIV was once a death sentence. Today over one million Americans are living with it, thanks to effective medical management.

Epidemics had lost the terror they formerly held for Americans, principally because we listened to medical experts and took their advice. With this new virus’s power, we’ll find out how well we have learned lessons from the pandemics of the past.

Featured image: A corpse is lifted from the back of a wagon during the 1832 cholera epidemic. Coloured lithograph, c. 1832. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Vintage Ads: Selling Health and Hygiene During the 1918 Pandemic

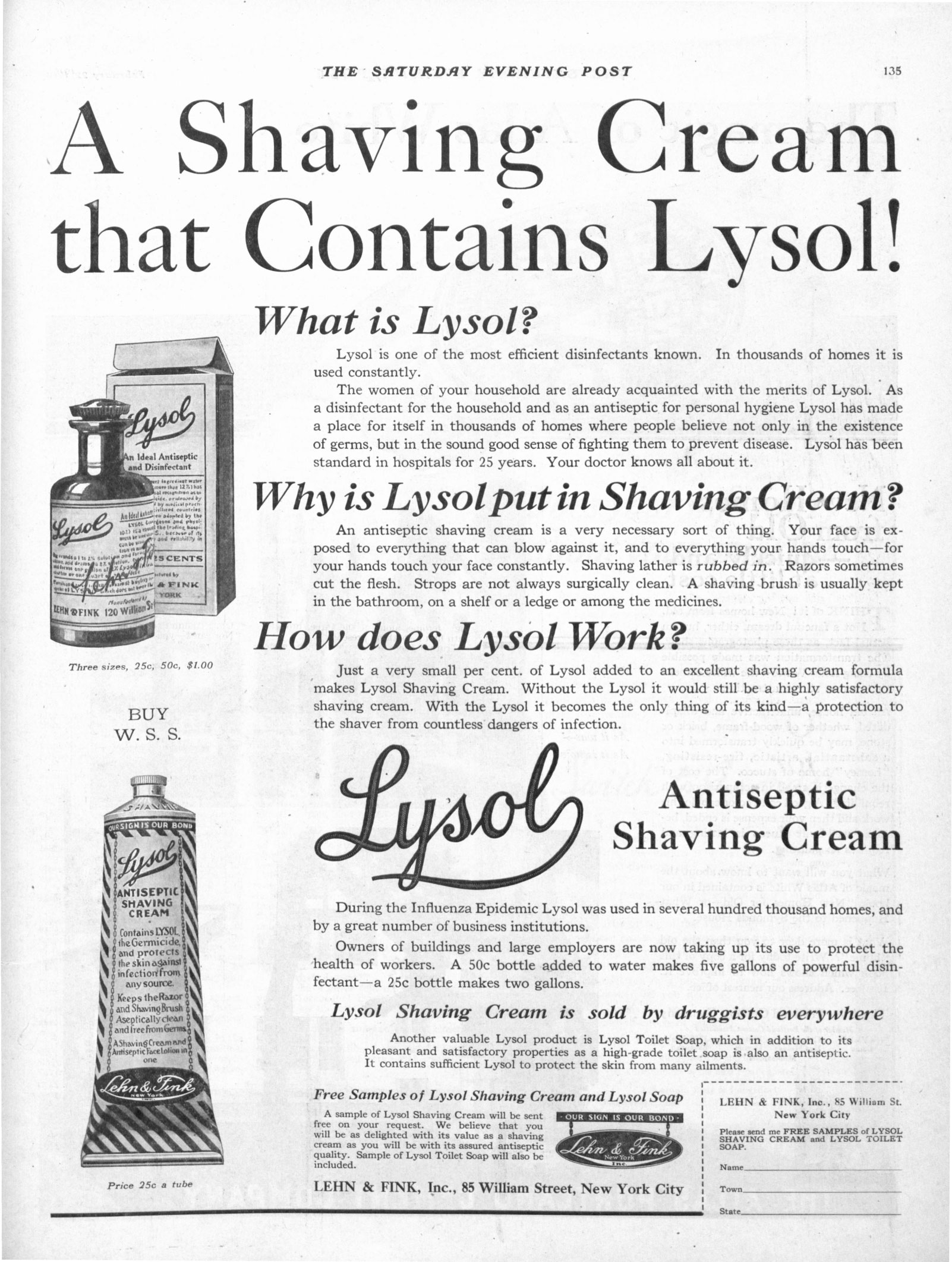

February 22, 1919

“During the Influenza Epidemic Lysol was used in several hundred thousand homes, and by a great number of business institutions.” (Click to Enlarge)

February 2, 1918

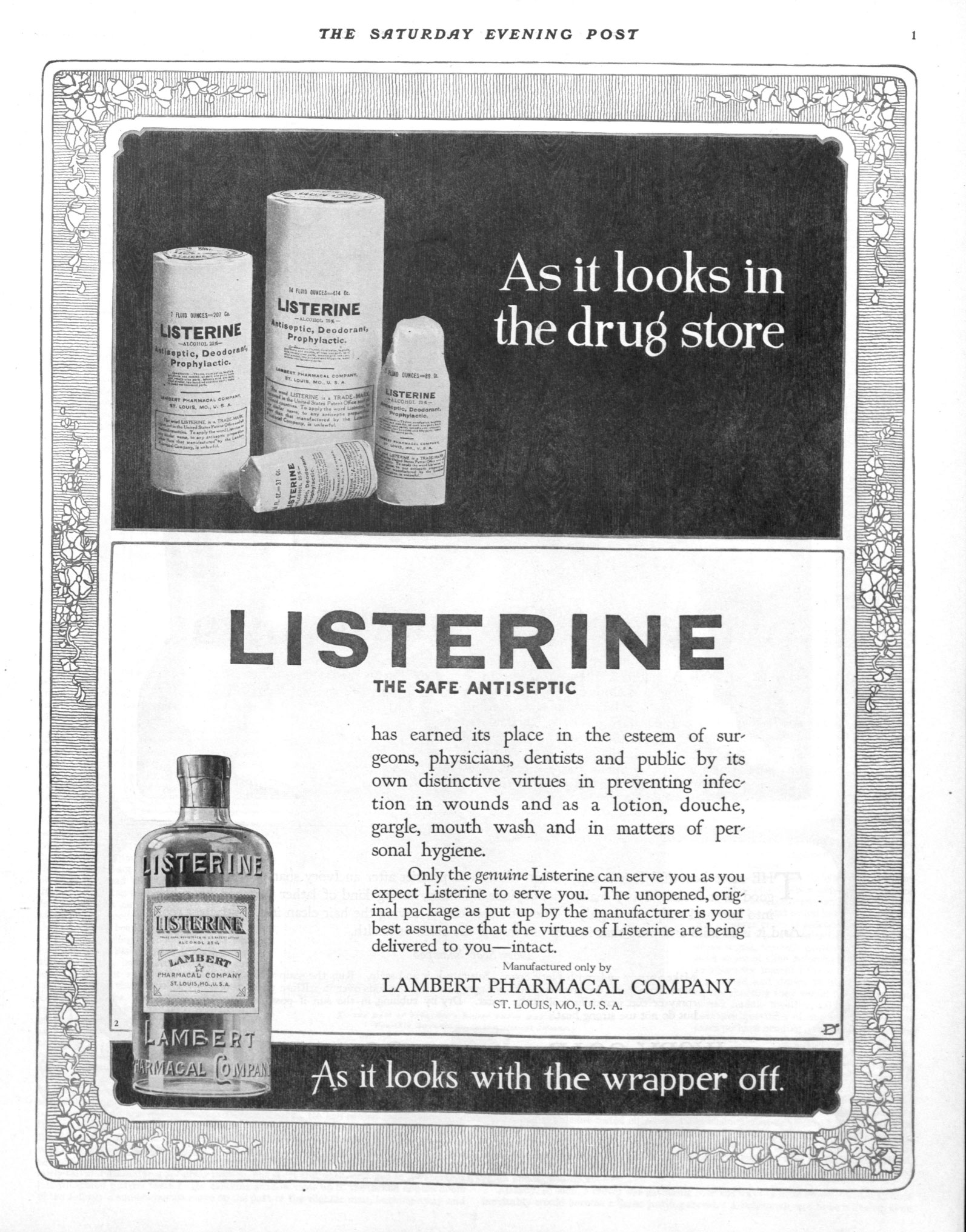

“…has earned its place in the esteem of surgeons, physicians, dentists and public by its own distinctive virtues in preventing infection in wounds and as a lotion, douche, garble, mouthwash and in matter of personal hygiene.” (Click to Enlarge)

February 8, 1919

“High ideals and cheerful service—Toilet and Hygienic Preparations of a purity to satisfy the most exacting standards.” (Click to Enlarge)

February 8, 1919

“Epidemics and typhoid have resulted from the use of unsanitary, wrong-principled water coolers.” (Click to Enlarge)

February 8, 1919

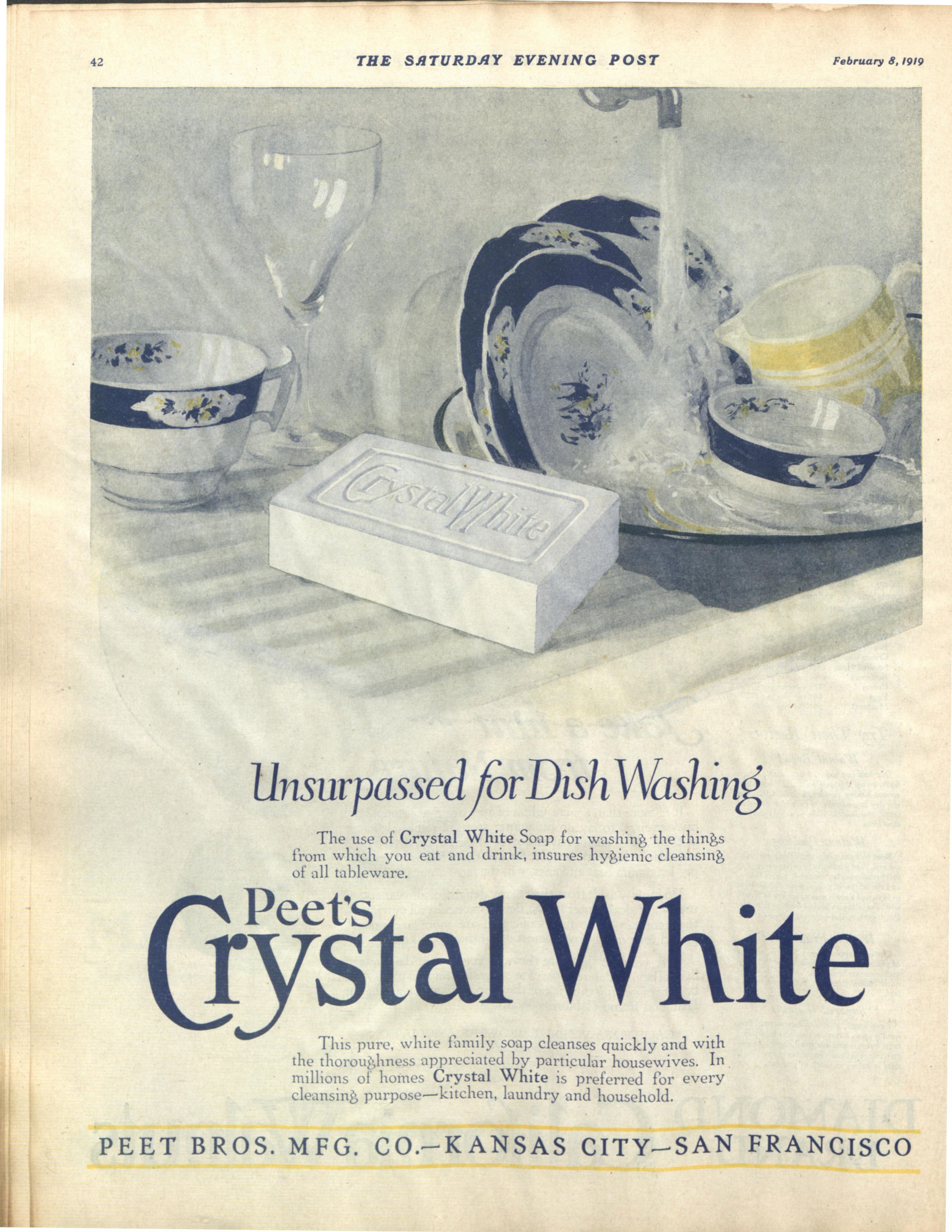

“This pure, white family soap cleanses quickly and with the thoroughness appreciated by particular housewives.” (Click to Enlarge)

December 28, 1928

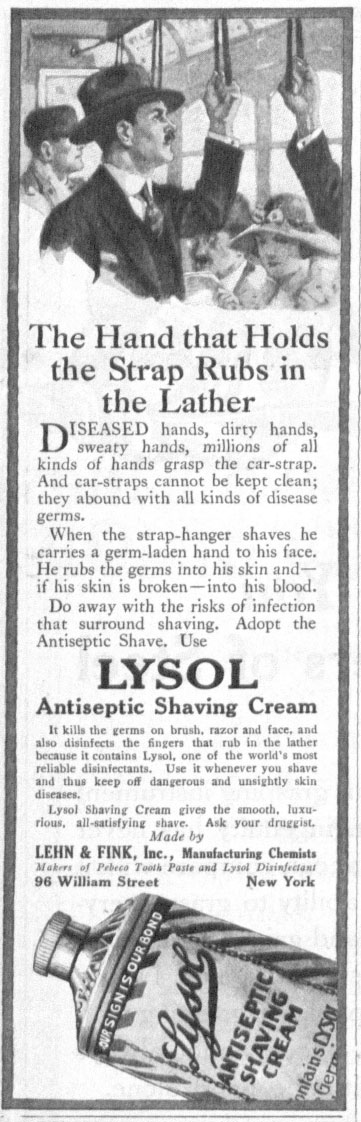

“Diseased hands, dirty hands, sweaty hands, millions of all kinds of hands grasp the car-strap. And car-straps cannot be kept clean; and they abound with all kinds of disease germs.”

April 20, 1918

“…colds, influenza and grippe are contagious, too. Their germs should be destroyed. So with all germs that lurk in dark places or breed in close rooms. The way to rid the home of them is gaseous fumigation.” (Click to Enlarge)

March 8, 1919

“To combat coughs, influenza and pneumonia, see that the air in your home is not only warmed but that it is AUTOMATICALLY circulated; that it is AUTOMATICALLY moistened; and that it is permanently free from dust, gas and smoke.” (Click to Enlarge)

Your Health Checkup: What You Need to Know about Epidemics and Pandemics

My wife and I just received our annual flu shots along with a pneumonia vaccination for good measure.

As a physician — no, even as an average adult – the controversy surrounding vaccinations continues to astound me. Vaccination ranks as one of the all-time greatest medical breakthroughs, along with the discovery of antibiotics, statins and other innovative medical accomplishments. Yet, many people fail to take advantage of this simple life-saving technique Edward Jenner discovered in 1796. How parents can risk their children’s health and lives by refusing to have them vaccinated is beyond my comprehension. The myth that vaccination increases the risk of autism has long been disproven. Failure to vaccinate exposes the population to the threat of contracting measles, mumps, and other preventable diseases, as recent experience has shown.

Sadly, in many parts of the world and for many infections, preventive measures such as vaccinations don’t exist. Poorer countries often cannot adequately contain some infections because they lack basic primary health care or health infrastructure or have deep-seated distrust of health care services. These deficiencies raise the specter of a global pandemic; i.e., a disease that could spread from one country to many or even worldwide.