The Premier Pantomime Cartoonist

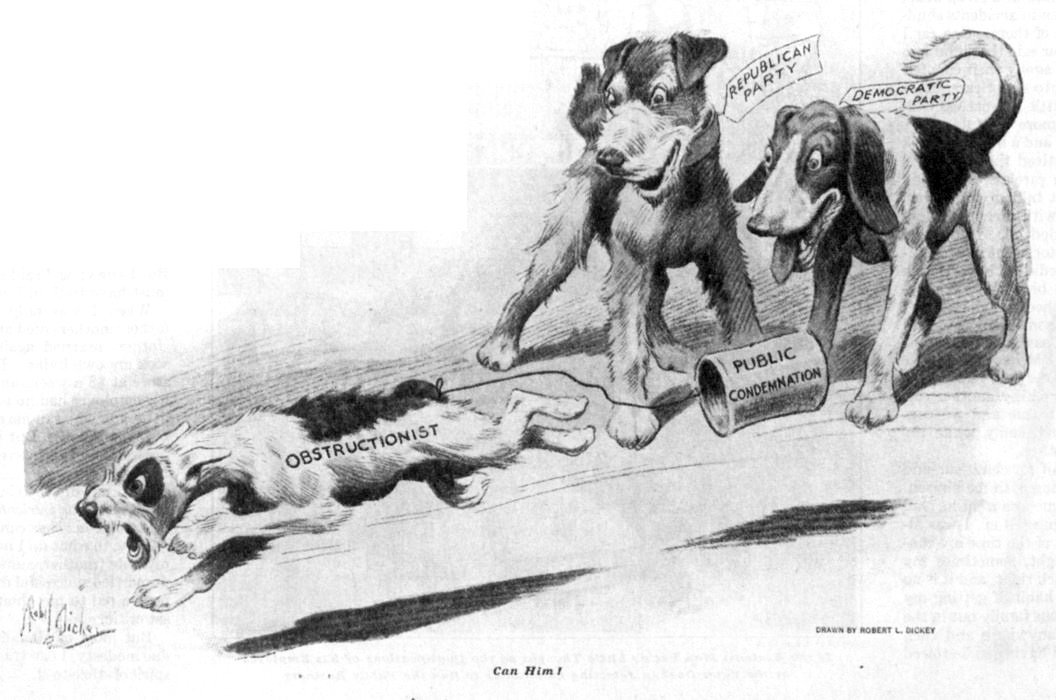

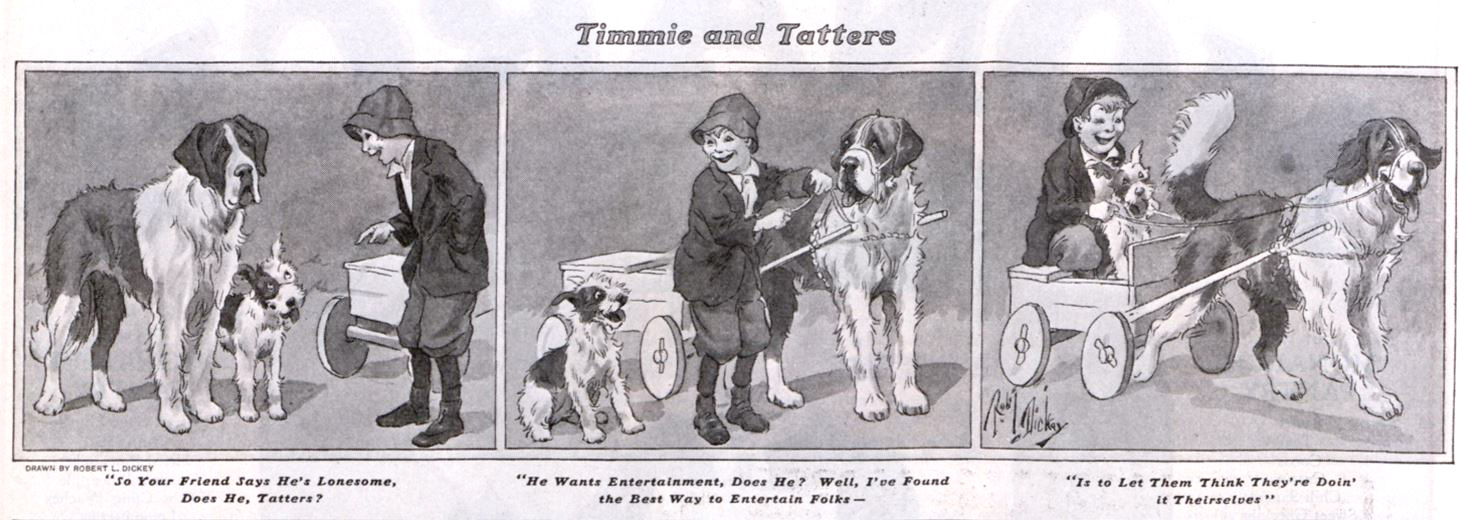

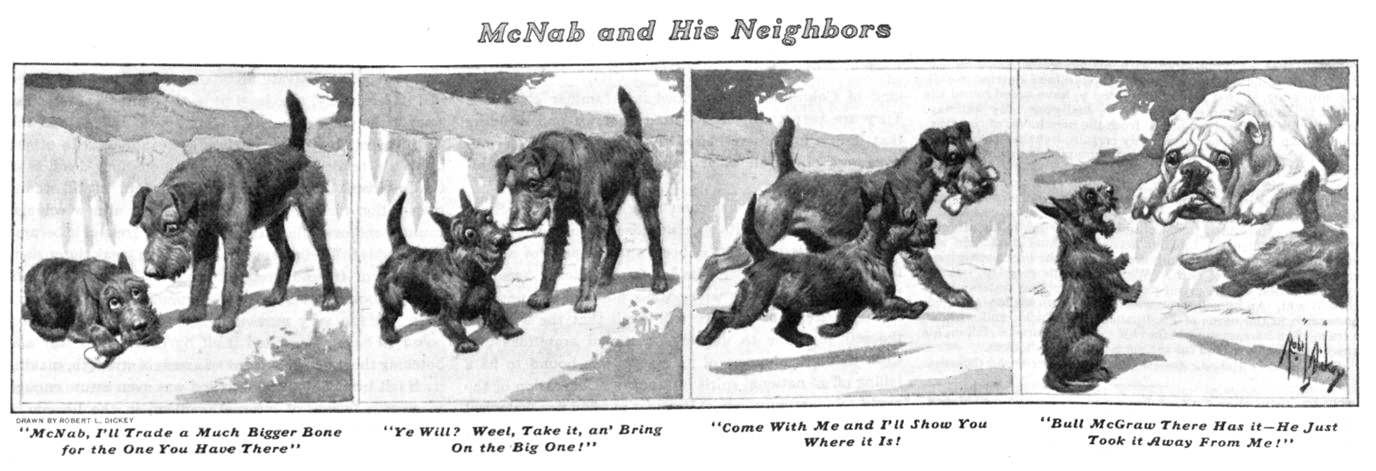

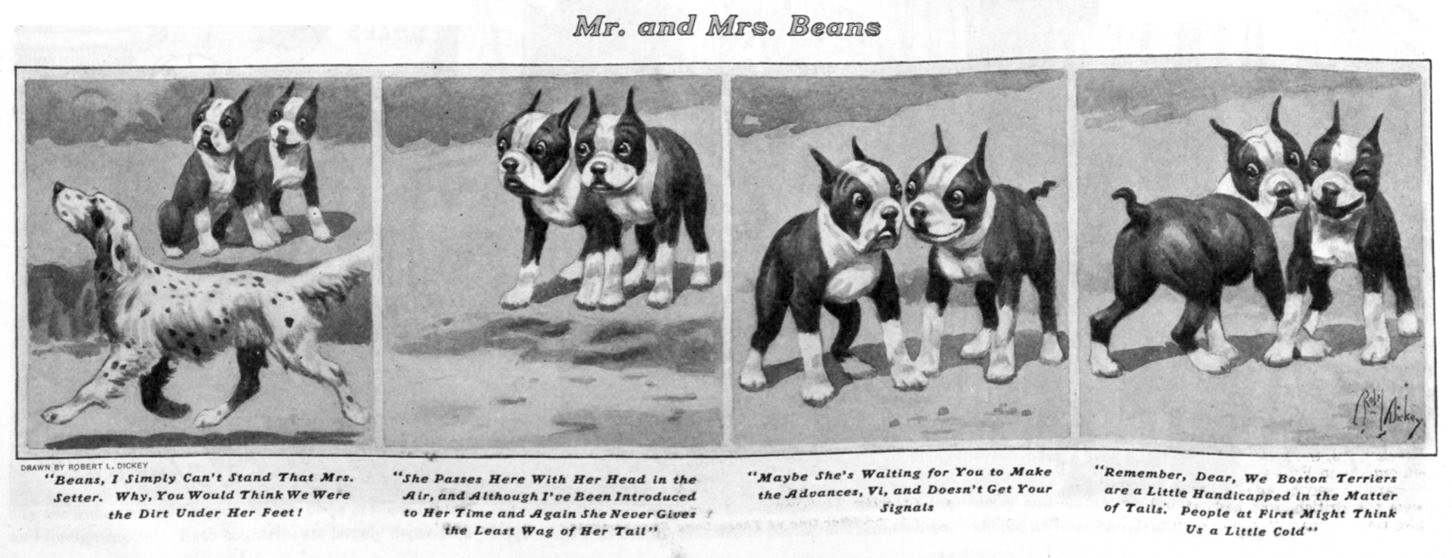

If you looked at a newspaper or magazine cartoon in, say, the 19th century, it might seem a little … off. The illustrations were packed with pen strokes, and captions were often comprised of two to four lines of wordy dialogue, resulting in the effect of a short conversation between two sketched characters.

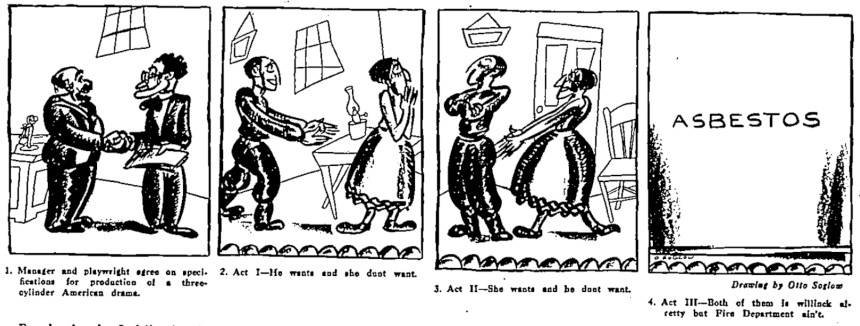

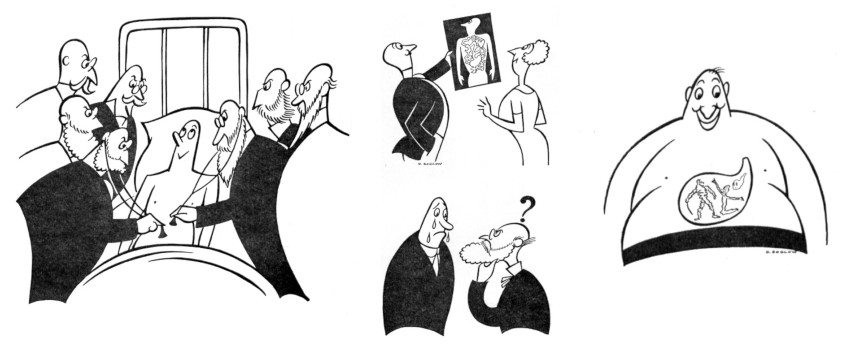

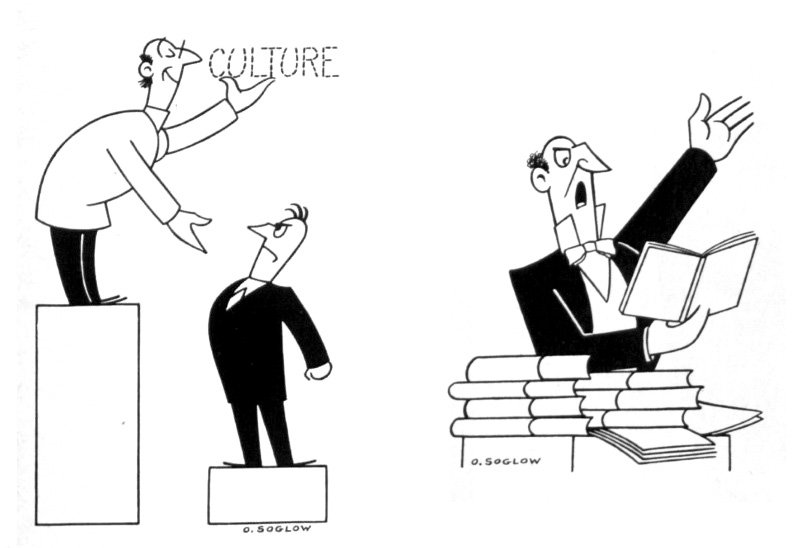

One of the cartoonists responsible for upending this style — and pioneering the kinds of strips we know today — was Otto Soglow, born on this day in 1900. At The New Yorker and, later, in this magazine and newspapers across the country, Soglow pared down lines in his illustrations, presenting a clean, minimalist rendering of whimsical characters. In the way of captions, uniquely, he often used very few or none at all, making a name for himself as a pantomime cartoonist with his popular strip The Little King, which ran for almost 40 years.

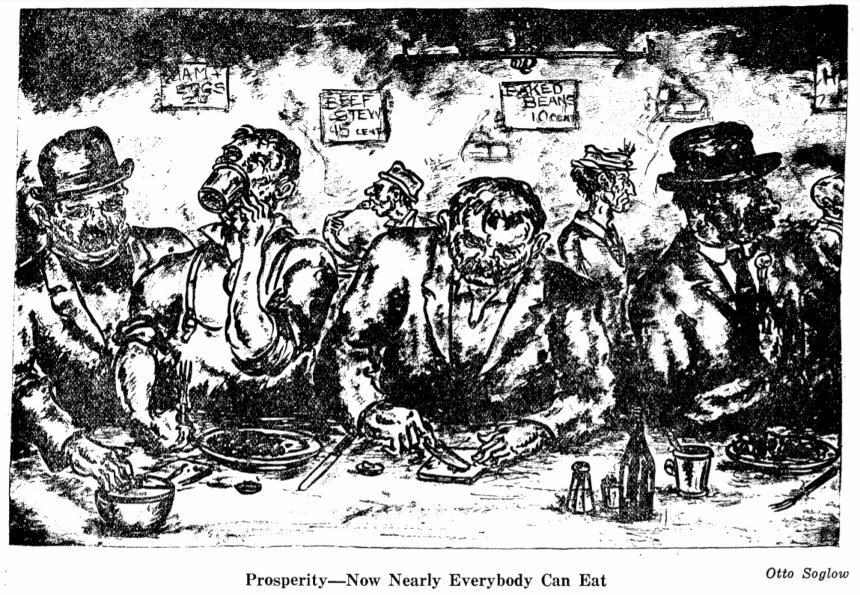

Soglow didn’t set out to become a cartoonist. A passionate performer, he dropped out of high school to pursue a career in acting. He worked as a shipping clerk, a packer, and even as a baby rattle painter before taking up illustrating professionally. In the 1920s, Soglow drew toons for the pages of radical New York publications like The New Masses and The Liberator. Influenced by the politics and aesthetics of the Art Students’ League, his work during this time depicted gritty cityscapes, working-class scenes, and socially-conscious themes.

In the August 1922 issue of The Liberator, which had published one of Soglow’s earliest illustrations the month before, the editors apologized for neglecting to credit him, saying “Soglow is to give the Liberator more of his strong work, so full of atmosphere, poetry, and sensitive observation.”

By the late ’20s, he was publishing toons and small illustrations in The New Yorker, alongside names like Peter Arno, Helen Hokinson, and James Thurber. In the magazine’s obituary for Soglow, the author noted that while his style was once busy with ink, it became purer over the years, eventually omitting all details except the most necessary: “There was nothing to distract the eye or the mind.” The New Yorker was also where Soglow introduced his most famous and enduring character: the little king.

In various weekly adventures for more than 40 years, Soglow’s “cartoon monarch” stumbled through silent, playful scenarios at the perplexity of his royal court. Far from a stereotypical depiction of a severe ruler, Soglow’s childlike king displayed no interest in power, but rather enjoyed simple pleasures like ice cream and zoo animals. While his barrel-chested guards smoked cigars, the short stubby sovereign blew bubbles out of a toy pipe. Soglow’s sight gags in his Little King strips — which were syndicated in papers around the country from 1934 to 1975 — were endearing nods to our better, more innocent, angels.

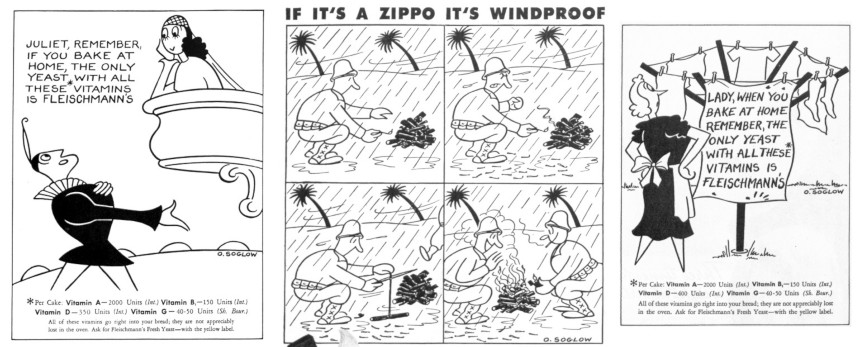

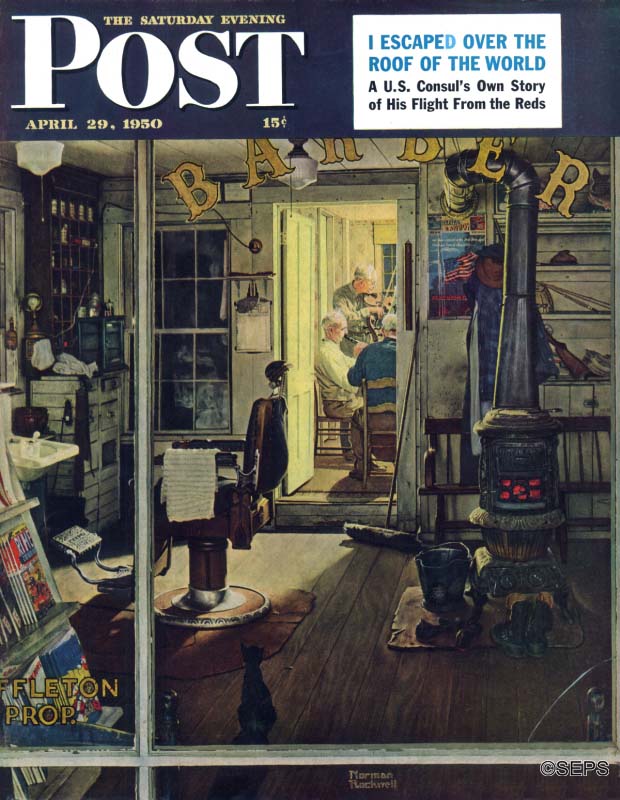

In taking his cartoons to a larger audience, the once-socialist Soglow struck a deal with newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst. If this move wasn’t quite contradictory, his career quickly took a commercial turn as he began illustrating ads for Realsilk socks, Mutual Life Insurance Company, Fleischmann’s Yeast, Pepsi-Cola, oil companies, and others. His ads — of course, lacking the quaint charm of his other work — appeared in The Saturday Evening Post for decades. Soglow was also a staunch supporter of the war effort, designing propaganda posters and supporting art programs for soldiers.

Although he likely made a great deal of money illustrating and cartooning, Soglow never lost his desire to perform. New York newspapers in the ’30s and ’40s described him as a hit at parties, giving impersonations and magic tricks that rivalled Chaplin’s. Given his earlier penchant for the poetic and the critical, discerning audiences might be tempted to read some semblance of subtle geopolitical commentary into The Little King, but Soglow said that was baseless and “just plain silly.” As for the origin of the beloved character that graced funny pages for decades, he gave no deep, revelatory explanation; “He just happened.”

Soglow drew The Little King until he died in 1975. Although he isn’t remembered widely by the populace, the cartoonist is decidedly among the ranks of important New Yorker illustrators, and the magazine still uses his artwork in print and online. In a review of a new Little King coffee table book in 2012, Jeet Heer called Soglow “one of the central cartoonists of mid-century America.” Flipping through the comics of any paper in the country before and after Soglow, it would be difficult to disagree.

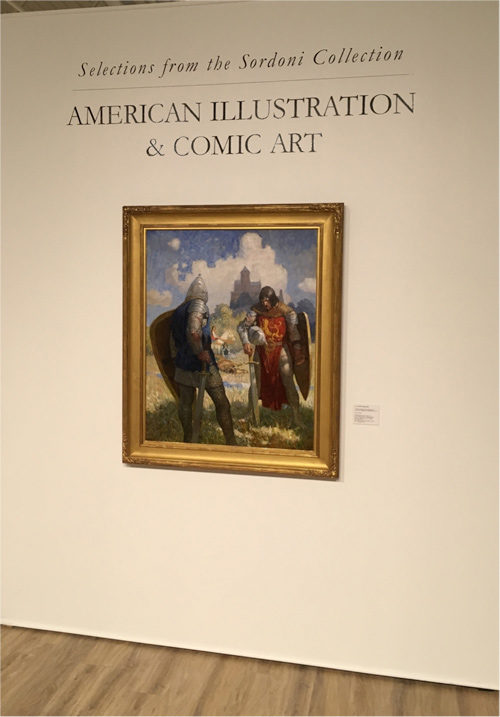

“Who Says I’m Uncultured?”/ “Let’s Keep the Filibuster,”The Saturday Evening Post, June 16, 1962, July 14, 1962

“The Art Movement in Real Estate” by Lucian Cary

Over the course of his career, Lucian Cary contributed more than 60 short stories to publications such as Collier’s, Ture Magazine, and, of course, The Saturday Evening Post. He was also a notable spokesperson for rifles and firearms, but assured Post readers in 1935 that his passion was but a “reasonable enthusiasm.” In “The Art Movement in Real Estate,” Cary tells the relatively peaceful tale of a peculiar group of artists living together in a picturesque Long Island town.

Published on October 30, 1920

Deep Harbor is a village of white houses with green blinds fifty-two miles from New York. Fifty-two miles has always been too far for any but the hardiest commuters. Fifty-two miles means getting up in the dark of wintry mornings to catch the six-fifty-five train. The price of real estate reflects the fact. A piece of land on the Sound big enough for a country estate has always been priceless, but a house in the village has long been cheap. Indeed, houses have often sold of late years in Deep Harbor for a good deal less than it cost to build them. And the highest known rental was thirty dollars a month, which secured a colonial mansion of fourteen rooms set in five acres of park with trees older than the town debt.

Ten years ago an impecunious illustrator discovered this delectable village. His visits to art editors called him to New York only once in ten days, even in his luckiest months. The fifty-two miles did not so much matter: The white houses with the proportions of Greek temples, with small-paned windows, with real fireplaces did matter. Steve Laidlaw loved them, and so did his wife. Those white houses awoke some desire in them that the most elegant of studio apartments in New York did not so much as stir. Besides, a white house with a barn and four apple trees and a place for a garden was actually within their reach. They bought it with what cash they could scrape up, put a studio light in the barn, and settled down to raise a family, with Rhode Island Reds on the side.

The next spring Arthur Millingham, who does those humorous drawings in color for magazine covers, and Bill Montaigne followed the Laidlaws to Deep Harbor. A landscape painter, passing through when the apple trees were in blossom, dropped off to stay a week and remained to buy a white house with lilacs in the dooryard. Another year Joe Hartley moved from Brooklyn to Deep Harbor with his whole retinue of satellites and pupils, a veritable school of illustration.

In time the village acquired a curious flavor — a piquancy. The original New Englanders possessed their full share of that strange power which enables them to take in the outlander without being themselves modified. They ran the town as they had run it since 1674; they elected the selectmen; they owned the bank; they made the roads as they had always made them, exactly as if the automobile and the motor truck had not been invented. But they, whose ancestors had admired the Greek, were tolerant of art. The illustrators found themselves free to wear their old clothes every day, to turn barns into studios of a spaciousness known only to millionaires in New York, free even to argue in the village square whether Gaugin was the most sophisticated or the most primitive of painters, or no painter at all.

As they learned more of the country of their adoption they complained bitterly among themselves of the schools and the roads and the fact that when one of them bought a house from a native and put a bathroom in it the assessment was promptly doubled on the tax list. But their complaints were only proofs of their affection. They liked Deep Harbor, and felt that they owned it, or at least that it had been created for their especial benefit. As Bill Montaigne always said when he broke a spring going over the bumps in the road that led from his house to the village center: “Anyhow, it isn’t suburban.” And Steve Laidlaw, who had been born in the Dakotas and gone to art school in San Francisco, and wandered from Yucatan to Nome, and from Honolulu to Valladolid, and never stayed more than a year in one place before, called it “home.”

II

To this Arcadia came Jimmy Dowling one blustery afternoon in November. Jimmy presented himself at Steve Laidlaw’s studio about the time the daylight failed and Steve turned on the powerful electric lamp above his drawing table. Steve was engaged in finishing the second of three drawings he had promised to deliver the next morning to an art editor in New York. He had figured that he could finish the third before eleven o’clock that night and drive to Bridgeport in time to catch the midnight mail train. He did not intend to be interrupted by anybody. He did not get out of his chair when Jimmy knocked; he yelled “Come in!” and went on drawing. But when he saw Jimmy he instantly laid down his pencil and kicked a chair nearer the big stove and hunted for the cigarettes. Jimmy was a boy of perhaps twenty-two or twenty-three with the look of one who hasn’t had a good meal for two days. He sat down abruptly and lighted a cigarette with fumbling fingers and looked at Steve with eyes like those of a setter pup who has wandered from home and been kicked and lost his illusions. Steve told Ann afterward that he guessed Jimmy’s story in that first minute. He had met it before. Jimmy had spent a season or two at the Art Students’ League and now he had come to the end of his father’s patience.

“I haven’t any excuse for interrupting you at your work, Mr. Laidlaw,” Jimmy said. “I don’t know why I came — except that I’ve always admired your stuff — and imitated it as much as I could. I just thought I’d have to see a real illustrator once before I — before I went back to Dayton, Ohio, and my father.”

“That’s all right,” Steve said. “Is your father a businessman?”

“Yes,” Jimmy said.

Steve grinned.

“My father was a farmer.”

Jimmy grinned back at Steve.

“That’s just as bad, isn’t it?”

Steve laughed.

“It was pretty bad,” he confessed. “I had to farm or else get out. So when I was seventeen I got out.”

“How did you get along?”

“I don’t know, but I did — somehow. You can if you have to.”

“That’s just it,” Jimmy admitted. “I don’t know that I have to be an artist. I don’t know but I ought to go back to my father’s office.”

Steve reflected that Jimmy was hardly the type to fight his way up. He looked intelligent but he didn’t look strong. He himself had stood six feet at seventeen and done a man’s work in the threshing field and on the San Francisco docks.

“Have you got any money at all?” Steve asked.

“I’ve got the price of a ticket to Dayton,” Jimmy said.

“H’m,” said Steve thoughtfully.

“I know I’m interrupting you,” Jimmy said. “I wish you’d go on with your drawing. I’d like to sit here and watch you work for a few minutes — and then I’ll go.”

Steve picked up his pencil.

“I am in a rush,” he admitted. “But you’re going to stay to dinner with us, and spend the night, and in the morning when I’m through with this job we’ll talk.”

“Gee!” said Jimmy Dowling, and somehow managed to put into that small word a great deal of the gratitude he felt at being thus accepted by Steve Laidlaw.

The next morning Steve led Jimmy round to Hartley’s place and introduced him to Joe and the three young chaps who were working under his tutelage. Hartley had worked out a system suggested by a reading of Vasari’s lives of the painters. His own work was in great demand but it pleased him to spend a great deal of his time in trying to teach young men his own skill. He was an entirely self-taught draftsman himself. He did not call his establishment a school, but a shop, and his young men were anything you pleased except pupils. He was always plugging for them with art editors, and when one of them got a commission he saw to it that the commission was satisfactorily executed even if he had to go over every square inch of the drawings with his own masterly hand.

“Want to join my gang here?” Hartley asked. He was a small man with a big voice, a voice that rather overawed Jimmy.

“Why,” said Jimmy, stammering and blushing, “II-I’d1-1-like t-to. But I haven’t got any money.”

“Who said anything about money?” roared Hartley. “If you have any talent I’ll show you how to make money.”

“I d-d-don’t know if I’ve g-g-g-got any talent,” Jimmy stammered. “The Art Students’ League said I hadn’t.”

“What do they know about talent? “ roared Hartley. “I-I-I-I d-d-don’t know,” Jimmy said.

“They don’t know anything!” said Hartley. “You come round here tomorrow morning and we’ll find you a table and you go to work.”

Afterward Jimmy admitted to Steve Laidlaw that he wished he had the nerve to accept Hartley’s offer.

“Why don’t you?” Steve asked.

“I’ve only got fifty dollars.”

“I’ll lend you another fifty,” Steve said. “Be glad to. And in time Hartley’ll get you jobs to do. You might make a go of it, you know.”

“Think I might?” Jimmy asked. “Of course. Why not?”

“I don’t know,” Jimmy said. “I just can’t see myself making a living out of art.”

Steve couldn’t see Jimmy making a living at anything but, as he said afterward to Ann, “You never can tell.”

Jimmy stayed on with the Laidlaws a week, and after a day or two he joined Hartley’s gang, and after a week he insisted on finding a place of his own to live in. Steve knew a little old house of the sort that the early Connecticut farmer built round a chimney and that he thought might be cheap. He took Jimmy to see it. Jimmy was entranced at the idea of having a house of his own. But the owner did not wish to rent. She wished to sell.

“How much do you want for it, Mrs. Thorpe?” Jimmy asked.

“I’m asking fourteen hundred dollars,” Mrs. Thorpe said.

“I’ll tell you what,” Jimmy said, “I’m short of cash just now. But I’d like to buy it. Suppose you give me an option for six months at fourteen hundred dollars.”

Mrs. Thorpe nodded.

And in the meantime,” Jimmy continued, “you rent it to me for ten dollars a month.”

“Would you pay ten dollars a month?” Mrs. Thorpe asked.

“I would if you’d let me use the furniture,” Jimmy assured her.

So it was settled by the magic of Jimmy’s phrase, “option for six months.”

Everybody in the Deep Harbor crowd kept an eye on Jimmy and saw that he got a good dinner occasionally and never went really hungry.

And if Jimmy had had just enough talent for drawing to hang on in Hartley’s shop he might have become an illustrator and even have earned his living at it. But he hadn’t any gift for drawing. Hartley hated to admit it, but the Art Students’ League had been entirely right in its estimate of Jimmy. It was in January that he told Jimmy the truth.

And if Jimmy had been the unhappy young vagabond he looked he might have gone on, leaving his several debts behind him, and Deep Harbor would have known him no more, and nothing would have happened.

But Jimmy wasn’t that sort.

He couldn’t bear to treat Steve Laidlaw and his wife thus, nor Bill Montaigne, nor Joe Hartley, nor the Russells.

He spent three days pacing the floor of the little house, and thinking out a scheme by which he could repay them not only the money he had borrowed but the kindness he had received; and in the end he evolved a plan, which he mightily resolved to execute.

III

On Sunday morning Ann Laidlaw addressed her husband.

“Now what do you suppose this means, Steve?”

“What?” said Steve.

He did not even look up from the sporting page. “Listen.” And she read aloud from the classified columns in the Times:

“’For sale: Colonial house of six rooms with studio; more than a hundred years old. Four fireplaces, original quaint iron latches, and small-paned windows; the home of a painter; charming Connecticut village; unspoiled; artist colony; fifty miles from New York, on the Sound and river. $3,000. Golf club, express stop, peace.”’

“What’s that?” Steve asked.

“You didn’t listen.” Mrs. Laidlaw read the advertisement aloud again.

“Whose ad is it?” Steve asked.

“I don’t know. It says: ’Address RX2, The Times..’ But it must be somebody in Deep Harbor. We’re the only town fifty miles from New York on the Sound. But whose house is it?”

“Might be Millingham’s. He was talking last fall about moving nearer New York.”

“The Millinghams have talked about moving nearer New York every winter for six years. Besides, they’ve got seven rooms and two fireplaces. It might be the Binghams’.”

“Their house isn’t a hundred years old.”

“Well, whose is it?”

Steve got up and leaned over Ann’s shoulder and read the advertisement with his own eyes.

“Damned if I know,” he said.

“But, Steve,” Ann said, “we know every house in town that’s got a studio. We ought to be able to figure out what house this is.”

“And what if we could?” he said. “What difference does it make?”

“But, Steve, aren’t you interested?”

“No,” said Steve, “I’m not interested in any ad that calls Deep Harbor an artist colony. Deep Harbor is a Connecticut village.”

In the afternoon Steve got into his rubber boots and started out to find somebody to talk to. It had been a real winter and there was still enough snow to make walking necessary. Steve wandered down the road with no very definite objective. At the corner where the village street joined the Post Road it occurred to him that he hadn’t seen Jimmy Dowling for a week. He crossed the road and walked on toward the Thorpe house. As he approached it he noticed that the woodshed had been moved from its position behind the house and now stood almost beside it, one corner touching the northeast corner of the house.

“That’s funny,” Steve said to himself.

He knocked on the door. He waited three minutes without getting an answer. He had turned to walk on when Jimmy Dowling opened the door. He was wearing a fresh, not to say new, painter’s smock. Now whatever may be the convention in their illustrations, it is not the custom of illustrators to wear painters’ smocks in their houses. Indeed, the smock which incased Jimmy Dowling was the only garment of the sort that Steve had ever seen in real life. Steve eyed Jimmy with a growing disfavor. He shook his head.

“Take it off, Jimmy,” he said. “Take it off before anybody else sees you. It won’t go.”

Jimmy grinned uncomfortably. “I wouldn’t have put it on if I’d known it was you, Steve,” he paid.

He seized his skirt with both hands and, lifting them high above his head, removed the smock with a single gesture.

“Come into the studio and I’ll tell you about it.”

“Studio?”, said Steve. “I didn’t know you had a studio.”

“Well,” said Jimmy, “it was the woodshed, but I’m learning to call it a studio. I’m using it for a studio, and so I guess it’s perfectly honest to call it the studio.”

James led the way to the woodshed and Steve followed him.

“How’d you get this shed over here?” Steve asked as he entered.

“I got a couple of men to help me move it last week.”

Steve looked round. The most conspicuous object in the room was an enormous wooden easel with a canvas in place. The canvas had been painted black. There was a great shapeless splash of vermilion near the middle of it, but no man could have guessed what it was going to be. At least Steve couldn’t.

“What is it?” he asked Jimmy.

“Well,” said Jimmy, “I haven’t decided. It’s anything you please. Of course it isn’t finished.”

Steve looked at the painting with narrowed eyes. “No,” he said; “no, it isn’t finished.”

Against one wall was a stack of canvases. Steve advanced toward them.

“Those aren’t mine,” Jimmy said. “I just borrowed them.”

Steve paused. In the middle of one wall was a large Franklin stove. One leg had been replaced by a couple of bricks.

“Where’d you get that?” Steve asked.

“I found it in the attic.”

Steve sat down in one of those straight chairs that had once had a rush bottom, the sort of chair that is characteristic of New England kitchens.

“What’s the big idea?” he asked.

“Well,” said Jimmy Dowling, “I decided I’d just have to make some money.” He waved his hand at the room. “I’m going to sell this place.”

Steve looked puzzled. He didn’t understand how Jimmy could sell a house he didn’t own.

“I’ve been setting the stage a bit,” Jimmy explained, “but it’s perfectly legitimate, don’t you think?”

“But you don’t own it.”

“I’ve got an option on it until May first,” Jimmy said. “Don’t you remember?”

“Yes,” Steve said, “but I thought you had to pay about fourteen hundred dollars for it.”

“Yes,” Jimmy said. “Fourteen. hundred.”

“ Don’t you know that you will have to sell it for more than that to make any money?”

“Yes,” said Jimmy Dowling. “I intend to sell it for more than that. I intend to sell it for twice that. I’ve advertised it for sale at three thousand dollars.”

“Was that your ad in the Times this morning — that guff about a colonial house more than a hundred years old in an artist colony, the home of a painter?”

Jimmy blushed and squirmed.

“Well,” he protested, “I didn’t say a good painter, did I?”

Steve deliberately lit a cigarette; He didn’t know just why he resented that advertisement but he did resent it

“Was there anything the matter with that ad?” Jimmy asked. “Every word of it was true, wasn’t it?”

“That may be,” Steve said. “But if anybody comes all the way out here from New York on the strength of that ad and finds that there isn’t a plumb wall in the house and that your floors run up and down hill, and that you haven’t got running water, let alone a bathtub, they’ll be sore. ’

“I didn’t say the house had a bath, did I?”

“No,” Steve admitted; “you didn’t mention it.”

“I didn’t say the walls were plumb either. I said the house was more than a hundred years old. If it isn’t plumb that just proves how old it is.”

“Yes,” Steve said. “But you said the price was three thousand dollars. Do you think that anybody who sees this house is going to pay three thousand dollars for it?”

“Well,” said Jimmy, “that’s an asking price.”

“Asking!” said Steve. “Asking! Asking is good.”

“Steve,” said Jimmy, “you’re a corking illustrator. If I could draw the way you can for one year I’d give away the rest of my life and die happy. But on this real estate thing you just aren’t there. You don’t understand what makes real estate valuable.”

“No,” Steve admitted; “if this shack is worth three thousand dollars I don’t understand — I don’t understand it at all.”

“Let me explain it’ to you,” Jimmy said briskly. “You know how rents have gone up in New York, and all over the country, for that matter?”

“Yes, I have heard about that. I read the papers.”

“You know that there are thousands of people in New York who can’t afford to live there. They’re moving farther and farther out every year.”

“Yes,” Steve said. “But they aren’t moving to Deep Harbor. It’s too far.”

“It has been too far. But it won’t be too far much longer, the way rents are going in New York. Property in this neighborhood is going up.”

“Sure,” Steve said, “it’s going up. It’s worth ten per cent more than it was when we came here ten years ago, maybe twenty per cent, but not a hundred per cent. And a place like this is deteriorating. In ten years it’ll fall down. Why, fourteen hundred dollars is a high price for it. I wouldn’t pay that much.”

“But there are people nowadays who will pay more than that. You don’t seem to realize that there’s been a boom in old colonial. People go crazy over anything a hundred years old. Why, they’ll pay more money for a house like this than they would for a new one.”

“I know all about the old-colonial kind of thing,:’ Steve said. “Of course a piece of furniture that’s antique is worth money, even if it’s in rather bad shape. But it must be something that was elegant to begin with.

“A real old-colonial highboy may be worth a thousand dollars. We’ve got ourselves that we wouldn’t take three hundred for, even if Ann did get it for fifty. But you can’t get any more for a rickety old kitchen table than you can for a new one — not so much. And this house is in the kitchen-table class.”

“Surely — and it’s only three thousand dollars. Nobody expects to get a colonial mansion for that price.”

“No,” Steve said, “but he expects to get a roof that will shed rain, and windows that will open and shut, and floors he can walk across without going into low gear.”

Jimmy waved a tolerant hand.

“There’s another thing you don’t understand, Steve, and that’s what art does to real-estate values.”

“Art?” said Steve.

“Art,” said Jimmy. “Do you know the history of Greenwich Village in New York?”

“What about it?”

“You know that it was once a fine residence district, and then everybody moved uptown and values dropped and dropped and dropped, until it became almost a slum. And then artists went in there because they could get a whole floor in an old red-brick mansion for twenty-five dollars a month. Gradually they revived the old district, and the Sunday papers played up the story, and Greenwich Village became Bohemia.”

“Yes,” Steve said, “and all the nuts in the country flocked to it and ruined it.”

“That may be,” Jimmy Dowling said. “The point I’m making is that rents doubled and tripled and quadrupled.”

“Rents have gone up all over New York since the war,” Steve said.

“They doubled and tripled in Greenwich Village before the war, “ Jimmy countered. “And it was artists that did it. Just give any place in the world a name for being an artist colony and people will go there — people with money.”

Steve shook his head.

“That’s all very well, and it makes a good story, but I don’t believe it. I don’t think it was the artists who were the attraction. I think it was the houses. While Manhattan Island was getting more and more crowded the artists were improving those old houses; and when they were improved the pressure for a place to live had got too strong. People with more money gobbled up those houses.”

“Well,” said Jimmy Dowling, “why couldn’t that happen in Deep Harbor?”

“I dunno,” Steve admitted. “I just don’t think it will. And I think you had better be drawing than wasting your time on these childish schemes.”

“Hartley has fired me,” Jimmy said. “Fired you?”

“Yes; he said it was simply no use for me to keep on.”

“I see,” Steve said.

“And so don’t you think it’s perfectly legitimate for me to try to sell this house?” “Legitimate? Of course it’s legitimate. If you can get anybody to pay three thousand dollars for this house after he has seen it nobody has the slightest objection to your doing it. All I was trying to make you see is that you can’t.”

“Well,” Jimmy said, “I’m going to have a try at it anyway.”

Steve stopped at Hartley’s place on the way home.

“He can’t draw anything,” Hartley said.

“He just hasn’t got the stuff; he’s got all the will in the world but he just can’t draw. He’ll never be able to draw.”

“I suppose you’re right,” Steve admitted. He trusted Hartley’s judgment in this matter.

“It’s too bad,” Hartley said.

“Yes,” Steve said. “And the worst of it is that he can’t do anything else. He’s full of the wildest ideas.”

“He ought to be driving a truck.”

“He’s too much of a dreamer.” Steve laughed. “He’d be running into things.” Steve went home and told Ann all about it and when they had laughed over Jimmy’s absurd scheme for selling Mrs. Thorpe’s little house, so much the worse for age, for three thousand dollars, they fell suddenly sober.

“Steve,” Ann said, “I think we ought to do something for that poor boy. He must be terribly hard-up.”

“He’s so hard up that he’s gone a little bit crazy thinking about money.”

“Yes,” Ann said. “He probably hasn’t had enough to eat. People who go hungry get lightheaded.”

Steve was very thoughtful.

“Poor little devil. Hartley says he can’t draw. He’s never sold a picture in his life and he never will.”

“I’m going to get Katy to bake meat pies tomorrow,” Ann said, “and you can take two or three of them round tomorrow noon. That’ll mean he will get one good meal tomorrow, and I think you’d better give him some money.”

“I will,” Steve said.

Steve went round the next day. He paused as he approached Jimmy’s house. Steve wondered whether it had ever been painted. He decided that it had once been whitewashed. But it had now the color of wood that has been exposed to fifty years of New England weather.

Jimmy Dowling came to the door in his painter’s smock. It was no longer fresh. Indeed it looked as if it had been painted in for months.

“Hello,” Jimmy said. He took off the smock. “I put this damn thing on,” he added, “whenever anybody knocks, in case it might be a customer from New York. But of course as long as it’s you I’m glad to take it off.”

“How’d you get all the paint on it?” Steve asked.

Jimmy Dowling blushed.

“With a brush,” he said. “I thought it wasn’t realistic enough before.”

“I’ve got a meat pie Ann sent you,” Steve said.

“Fine,” said Jimmy Dowling.

“And,” Steve continued, “I — I — happen to be flush right now, and I thought if fifty dollars would help out.”

“Why,” Jimmy said, “I owe you fifty dollars now.”

“That’s all right,” Steve said. “I don’t need it.”

“Well,” said Jimmy Dowling, “I’ll give you a note for it — thirty days.”

“No,” Steve said. “You can pay me back when you sell your house.”

“All right,” said Jimmy Dowling. “I’ll be glad to get your fifty. I know where I can get a roomful of old furniture for that.”

“A roomful of old junk,” said Steve.

“You wait and see,” said Jimmy Dowling.

Steve took a small wad of bills from his pocket. He wished Jimmy Dowling were going to spend it for food, but it was not for him to say.

“There’s another fifty where that came from,” he said to Jimmy Dowling. “Just you let me know if you need it.”

“That’s awfully good of you, Steve, but I don’t think I shall need it — not if I sell the house anyway.”

Steve went home to discuss with Ann the possibility of finding a job for Jimmy Dowling.

“Do you think he’d take a job?” Ann asked.

Steve looked thoughtful.

“Maybe not now,” Steve admitted, “but he’ll have to do something pretty soon.”

IV

“For two weeks Steve was so busy with a rush job, illustrating a serial against time, that he thought very little about Jimmy Dowling. Ann noticed that Jimmy’s ad appeared in the Times on the first Sunday, but not on the second. She drew Steve’s attention to the fact.

“I suppose,” Steve said, “he didn’t have enough money to put it in again. An ad like that must cost five or ten dollars.”

Ann turned to the rate card and did some figuring.

“It cost at least nine dollars,” she said to Steve.

“Poor little devil.”

“We’ve got to find him a job,” Ann said. “Think what a state of mind he must be in, not knowing where his next meal is coming from.”

“Yes,” Steve said, “I know what state of mind he’s in. I’ve been there myself. I’ll look round and see if I can’t turn up something. The only thing is I hate to tell him I’ve found him a job. It’s just the same as saying that I think he can’t be an artist. And of course he thinks he can.”

“I thought Hartley told him he couldn’t draw.”

“I know,” Steve said. “But by this time he’s just persuaded himself that Hartley didn’t know what he was talking about. I know how it is. Lots of people told me I couldn’t draw.”

One evening just before dinner Jimmy came over. Steve sat down to talk while Ann went out to tell Katy to set another place at the table.

“Steve,” said Jimmy Dowling, “how much would you take for your place?”

“I don’t want to sell. It’s my home.”

“I know,” Jimmy said. “I didn’t ask you how cheap you would sell it. But suppose somebody came along and asked you to name your price?”

“ Why, I wouldn’t take ten thousand dollars for this place.”

“Well,” said Jimmy Dowling, “would you take twelve thousand dollars for it?”

Ann came in just then.

“You bet I would!” she said.

“Well,” said Steve slowly, “if I could actually get twelve thousand dollars I might fall. I hope I wouldn’t. But there isn’t any more chance of that than there is of your getting three thousand for the place you’re in.”

“I’m not in it anymore,” said Jimmy. “I sold it.”

“When?” said Steve Laidlaw.

“This week.”

“How much?” Ann asked. “Twenty-eight hundred.”

“What!” Steve cried.

“Twenty-eight hundred,” Jimmy repeated. “I made an even fourteen hundred dollars — less eighteen dollars and fifty-four cents for advertising.”

Jimmy produced a check book and a fountain pen.

“Here’s that hundred dollars I owe you,” he said, and tore a check out of the book. “I can paint for a year now, and nobody can stop me. I’ll have over a thousand dollars left after I’ve paid up everybody I owe.”

Steve and Ann stared at Jimmy Dowling.

“Who bought it?” they both asked at once.

“The nicest old maid you ever saw,” Jimmy said. “She told me it was the kind of place she’d dreamed about all her life. She’s going to put in a bath and a one-pipe furnace and flower boxes and live there the rest of her life.”

“I hope she’s going to put on some paint,” Steve said.

“No,” Jimmy said. “That’s one of the things she was most enthusiastic about. I hadn’t ruined the place with a coat of nasty fresh paint — it had the color that no painter could mix — the color that only Nature could give.”

Steve considered.

“Jimmy,” he said, “I hope you realize that you’re just plain lucky. You happened to find a woman who was crazy enough to want that house and who had the money to pay your price for it. Don’t gamble on finding crazy people with money.”

“Well,” Jimmy said, “I know I can’t draw but I do love to paint. If I can dabble in real estate enough to keep going, and spend most of my time painting, I’ll be happy.”

“Lightning,” said Steve cleverly, “never strikes twice in the same place.”

“Well,” said Jimmy Dowling, “I’ve rented another house, with an option to buy, and — well, you wait and see. I’ve got several things up my sleeve. And I do wish you two would keep this thing under your hats until I get a chance to spring my little stunt.”

“We won’t talk,” Steve assured him. “But I do wish you knew when to quit.”

On succeeding days there was a series of small teasing advertisements in the classified columns of the Times. They held out to the harassed rent payers of Manhattan the prospect of a happier way of life. They began with the time-honored question, “Why pay rent?” and concluded with alluring references to white houses and apple trees, but without describing any particular house.

Ann would not ordinarily have noted them. She read them now because her interest was up and she suspected Jimmy Dowling.

The last ad specifically described a house of nine rooms, in the colonial fashion, with a large studio and a view of the Sound, in an artist colony, at thirteen thousand dollars. Ann showed it to Steve on Sunday afternoon.

“Who has the nerve to put that price on his house?” Steve asked.

“It must be somebody we know,” Ann argued. “It says there’s a studio and it’s fifty miles from New York. Do you suppose it’s the Williamses?”

“They haven’t got any more view of the Sound than we have,” Steve said.

“We’ve got a view of the Sound,” Ann said roundly. “You can see the Sound from the hill back of the studio.”

“When there aren’t any leaves on the trees.”

“You can see it from our room, even in summer.”

“You don’t call catching a glimpse of the Sound from a second-story window having a view of the Sound, do you?”

“It is a view of the Sound just the same,” Ann said.

Steve got up and looked out of the window.

“You can’t see it from here anyhow,” he said.

Ann joined him at the window. As they gazed an automobile came to a plunging halt in the snow.

“Who’s that?” Steve asked.

Jimmy Dowling got out of the car. He was followed by a well-dressed man and woman of middle age. They began slowly to ascend the hill toward the Laidlaws’ front door.

“Good Lord!” Ann said. “They’re coming here, and you in corduroy pants and a blue flannel shirt, and me in a kitchen apron and the Sunday paper all over the living room!”

She flew at the room, piling up the Sunday paper, straightening the furniture, capturing a child’s toy. When the doorbell rang she disappeared upstairs.

“Hello, Steve,” said Jimmy Dowling. “Mr. and Mrs. Whittaker have come out from New York to look at your house.”

“Why — uh,” Steve gulped. “All right,” he said. “Come in, won’t you?”

They came in, they shook hands, they beamed upon Steve.

“I know your illustrations in the magazines,” Mr. Whittaker assured him.

“Yes, indeed,” said Mrs. Whittaker. “I think they’re perfectly lovely, but I never dreamed that I’d actually meet you. I’ve never met a real live artist before in my life. But even I can see you’re an artist just by looking at you.”

Steve stood on the other foot. He was not easily embarrassed among his own kind but he hadn’t learned how to accept the lay compliment gracefully, and he was entirely aware that he hadn’t. The fact that he realized his own ineptitude made it harder for him to think of something to say. But he found it didn’t greatly matter. It was unnecessary for others to hunt for words while Mrs. Whittaker was present.

She went into ecstasies over the fireplace with its warming oven; over the latches on the doors; over the wide oak boards of the floors in the second story. And then she insisted on seeing Steve’s studio. Steve hesitated. He was afraid Mrs. Whittaker was the sort who expected a place of Turkish rugs and old armor and Chinese curios. Steve’s studio suited him, but there was nothing arty about it, no more than there is in a carpenter’s shop. He was keenly aware of the pile of galley proofs containing the short stories he had illustrated and which he was accustomed to throw under the table as fast as he read them; of the rusty iron stove that heated the room; of the place about his chair, littered with pencil shavings and cigarette butts. Steve told himself he didn’t care what Mrs. Whittaker thought of his studio. He didn’t want to sell her his house.

But Mrs. Whittaker VMS not to be daunted by the studio’s want of elegance. “A-a-ah!” she said. “Now I have found a real studio — the workshop of a real artist. I’ve always wanted to know a real artist. I’ve always wanted to have a home that was an artist’s home. I’ve always wanted to sit in a studio in which real beauty had been born.”

Mrs. Whittaker turned to her husband.

“This is what I want,” she said. “Mr. Whittaker smiled amiably.”

“She usually gets what she wants,” he said to Steve.

Steve grinned weakly. Did these people really mean what they said or were they just talking? As they left, Steve reached out and collared Jimmy Dowling.

“What does this mean?” he whispered.

“Well,” said Jimmy Dowling, “I think they’re going to buy, don’t you?”

“Buy!” said Steve.

“Yes,” said Jimmy Dowling.

“But I don’t want to sell. Where would I go if I did? What did you tell them?” “Didn’t you read my ad — nine-room house with a view of the Sound for thirteen thousand? Of course my commission of five per cent has to come out of that, but if they buy you’ll get more than twelve thousand, and you told me you’d sell for twelve.”

“I hadn’t any idea that anybody would buy at that price. Didn’t I tell you I didn’t want to sell?”

“I’ll talk to you later,” Jimmy said.

“I’ve got to go along now.”

Steve stood watching Jimmy Dowling chaperon his clients into the car.

“Oh, Steve!” Ann cried.

Steve turned to her. Her face was aglow with hope. Steve regarded her glumly. “Ann,” he said, don’t understand you. I thought you loved this place — the thing we’ve spent ten years making. This house means more to me than any picture I’ve ever made or ever shall make. And

I thought you cared — too.”

Ann stood beside him and put her around his neck.

“You know I care, Steve. You know I love this place. You know I’m proud of it — busting proud.”

“Then why do you want to give it up?” “I don’t want to give it up.”

“Ann,” he said, “don’t lie to me. I could see it in your face — you want that thirteen thousand dollars.”

“Yes, I do — don’t you?”

“No,” Steve said grandly; “thirteen thousand dollars is nothing to me beside this house.”

“Steve dear,” said Ann patiently, “have you forgotten the Arkwright house?”

Steve sat down. Presently he lit a cigarette. Ann sat on the arm of his chair. Their eyes took on the gaze of those who see visions.

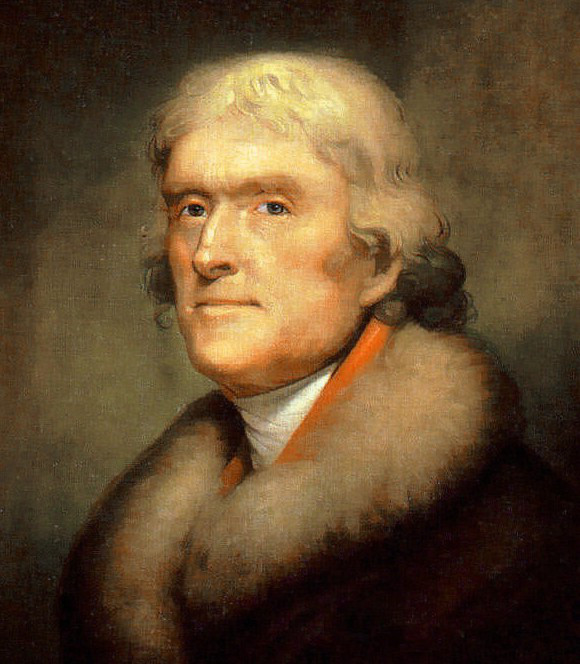

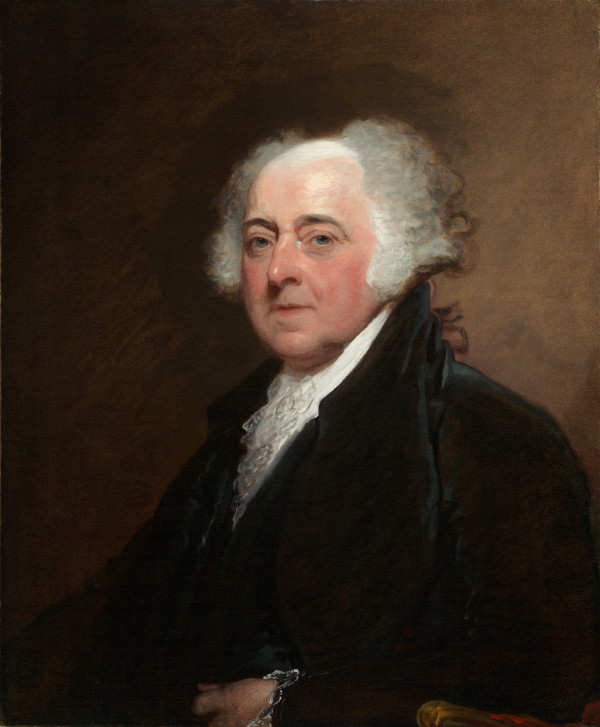

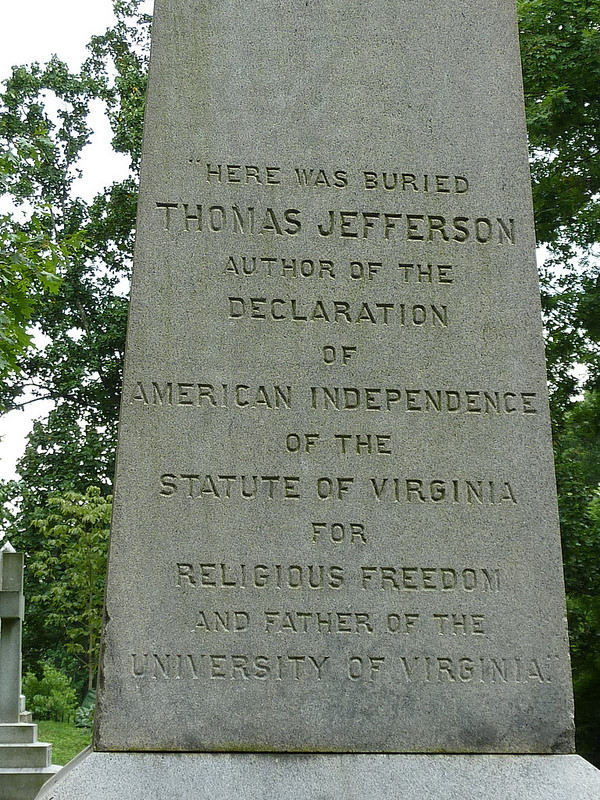

The Arkwright house had been built about the time George Washington entered on his second term as President. It was the perfect example of the colonial tradition — a large house-of beautiful proportions and matchless simplicity. You entered a hall baronial in size but intimate in feeling, a hall with its original floor of wide oak planks, its great fireplace set in a wall entirely composed of exquisitely made paneling. The rest of the house was like that, with a bedroom forty feet long, designed for use on occasion as a ballroom. And the setting was most perfect.

“Of course I haven’t forgotten it,” Steve said at last. “We talked about it for two years, but we knew all the time we couldn’t afford it.”

“We could afford it if we sold this place for thirteen thousand dollars.”

“Arkwright wants eleven thousand, doesn’t he?”

“Exactly,” said Ann. “Now do you see why I was excited over the idea of selling the place?”

Steve saw. What was more he began to feel Ann’s excitement. He wished he had been more gracious to Jimmy Dowling’s clients. He wished he had expatiated on the merits of his house. He could have told them about the garden. He could have shown them photographs taken the previous summer.

“Ann,” he said judicially, “they won’t do it.”

“How do you know?”

“It isn’t reasonable — thirteen thousand dollars for this house.”

“Why not?”

“Do you remember what we paid, Ann? Three hundred down and a mortgage for three thousand!”

“Oh, well,” Ann said, “we’ve practically rebuilt the place since then. What about the new wing, and the studio, and all the planting we’ve done? We’ve put in three thousand in improvements — at least.”

“At most,” Steve said.

“What about our work?”

“We did that for fun.”

“Of course. But we didn’t do it for the Whittakers. There’s no reason why they shouldn’t pay for it.”

They argued the worth of their house for half the afternoon, and discussed the possibilities of the Arkwright place for the other half.

About dusk Jimmy Dowling came in.

“They want to buy,” he said. He fumbled in his wallet. “Here, Steve,” he continued, “is his check for five hundred to bind the bargain pending the search of the title and that sort of thing.”

Steve looked at Ann and Ann looked at Steve and with a common impulse they both looked round their pleasant living room, with the mantel they had discovered on an abandoned farm in the back country, and the corner cupboard with its handwrought “H” hinges that they had found in a junk shop, and the oak settle that Steve had made out of planks from an old barn.

Jimmy Dowling shook the small strip of paper which meant so much more than the five hundred dollars it stood for — which meant giving up all this to a stranger.

“Here’s your check,” Jimmy repeated.

And into Steve’s mind there floated a picture of the Arkwright house, with the three great elms that shaded it, with its beautiful old living hall, with its bedroom that was a ballroom. He took the check, folded it without looking at it, thrust it into his pocket.

“All right,” he said grimly.

Jimmy Dowling rose.

“I’ve got to be on my way,” he said.

“But I hope you’ll come over and see my new house — it’s the old Wilkinson place.” Jimmy left. Steve paced back and forth.

Ann sat silent beside the fire.

“Are you sorry, Steve?” she asked. “Aren’t you?” he challenged.

“A little — but I know we’ll like the Arkwright house a thousand times better.”

“Sure we will,” Steve said. “And I’ll go down tomorrow morning and clinch the deal with old John Arkwright.”

“Let’s go over and see the Montaignes,”

Ann said.

The Laidlaws always went to see the Montaignes when anything happened. But on this night of nights the Montaignes weren’t at home.

V

On Monday morning Steve Laidlaw went down to Arkwright’s.

“I hear you sold your place,” John Arkwright said.

“Why, yes,” Steve said. “And I’ve come in to see you about yours. We want a place to live and we’ve always liked that place of yours.”

“I know it and I sort of felt I oughtn’t to do anything without letting you know. But it’s been three or four years since you and I were sort of dickerin’, and this chap sort of talked me off my feet.”

Steve sat down heavily.

“Have you sold it?” he asked.

“Well, now,” John Arkwright began, “I

wouldn’t say as I’d sold it. But I did give him an option.”

“Who?”

“Dowling,” said Arkwright. “He come in here a week or two ago with a story as how he thought he could sell it for a good price. He offered me a hundred dollars for a thirty days’ option at twenty thousand dollars.”

“Twenty thousand dollars?”

“Yep; twenty thousand dollars.”

“But you were going to sell it to me for eleven thousand dollars, John.”

“I know I was,” John Arkwright admitted, “and I would have, too; but this Dowling says property has gone up from fifty to a hundred per cent hereabouts.”

“It has, has it?’ said Steve.

“So he says. What did you get for your place, Steve?”

“Thirteen thousand.”

“So I heard,” said old John Arkwright. “And “ — he paused and lit his pipe and pressed the coals with a horny thumb” ain’t .that just about twicet what it was worth?”

Steve glowered.

“It’s more than I thought it was worth or I wouldn’t have sold.”

“’Course, ’tain’t your lookout what some fellah from New York pays,” old John Arkwright continued. “I suppose it’s worth it to him or he wouldn’t buy. Pshaw, I c’n remember when that house of yours sold for sixteen hundred.”

Steve walked slowly home. He was in no hurry to see Ann. Of course he had been a damn fool to suppose it was only his house that had risen in value as a result of Jimmy Dowling’s efforts. What would Ann say? He tried to think of a house in Deep Harbor that Ann would like. He was in a mood to buy anything that was for sale on the old Deep Harbor scale of prices. The Sherrill house might be for sale. It wasn’t such a beauty as the Arkwright

house but it was a fine old house. He decided to stop and have a look at it on the way home.

Steve had gone perhaps a hundred yards in the direction of the Sherrill place when he saw Bill Montaigne’s car coming down the road. Bill drew up.

“We were over to see you last night, Bill,” Steve said, “but you weren’t at home.”

“I wish I had been,” Bill said. “I might not have made such an ass of myself if I’d talked to you first. I sold our house.”

Steve flushed. “What?” he said.

“Yep. Twelve Thousand Dollars, cash.” Bill could not speak the words without a certain pride. But his face fell the moment he had spoken them. “We thought we’d take it and just go up the street and buy the Sherrill place. We’ve always liked it, only we never felt we could afford it.”

“And you found the price of the Sherrill place had gone up just as much as yours had?”

“They want eighteen thousand for it now!” Bill said.

“Didn’t you know that if your house was worth twelve thousand the Sherrill place would be worth eighteen thousand?”

“I didn’t think at all, Steve,” Bill admitted. “I wish I’d talked to you first. But I didn’t really have a chance. That young Dowling did it. He just brought some people out and I was sort of dazzled, I guess”

“I know how it is, Bill,” Steve said grimly. “I sold too.”

He repeated the details of the Whittakers’ visit and his talk with old John Arkwright.

Bill laughed.

“It’s nothing to laugh at, Bill,” said Steve soberly.

“No,” Bill admitted. “I’d like to wring young Dowling’s neck.”

“I’d like to have my house back,” said Steve. “I don’t dare go home and tell Ann the news.”

Of course he did go home and tell Ann the news. Ann burst into tears.

“It looks to me,” Steve said, “as if we’d have to leave Deep Harbor for good.” “Where’ll we g-g-go?” Ann sobbed.

The telephone interrupted Steve’s reply. It was Hartley.

“Do you know what has happened?” he roared. “That little shrimp of a Dowling has set this town crazy. Greenwood won’t renew my lease. He says he’s put the place on the market.”

“Why don’t you buy it?” Steve asked wickedly.

“He wants twenty-one thousand dollars for it.”

“It isn’t worth it,” Steve assured him.

“Worth it!” Hartley’s voice rose to a point that made the next sentence unintelligible over the telephone.

“Hartley,” Steve said, “I’m in the same boat. I’ve sold my house.”

“For how much?”

“Thirteen thousand.”

“You ought to be indicted!” roared Hartley.

During the week it developed that the

Millinghams and the Wilkies had given Jimmy Dowling options on their places, that Jimmy had already sold the Russells’ house, and the Binghams’, and the Williamses’. Real estate had jumped from one hundred to two hundred per cent in Deep Harbor. And even if the illustrator crowd had been willing to pay the new prices there weren’t enough houses to go round. The influx of half a dozen New Yorkers had created an actual shortage of desirable houses.

“I don’t understand it,” said Bill Montaigne. “How could prices change so much in two or three weeks?”

“The thing would have come sooner or later anyway,” Steve said. “Jimmy just happened to see it coming before anybody else did.”

“See it coming!” Hartley roared. “He hornswoggled us.”

Hartley was for. running Jimmy out of town on a rail. Bill Montaigne was for exploring the country three or four miles inland in search of cheaper houses.

“You know what the back-country roads are, Bill,” Ann said.

“We’ll improve them,” Bill announced. “We can go to town meeting and vote, can’t we?’

But a couple of trips into the back country over March roads disillusioned Bill. He dropped into the Laidlaws’ one night to report that he had to hire a team to haul out his car on three different occasions.

“You know,” he added, “this situation is really serious. We’ve got to give possession on May first and I can’t find a place to go. What are we going to do?”

“Let’s go and see Jimmy,” Steve suggested. “Let’s get everybody he has sold out,” Ann said. “I think we ought to put it up to him.”

“What can he do?” Bill asked.

“He can’t do anything,” Ann admitted. “But he acts as if he had done us all a favor. I think he ought to know what he has done to us.”

They started out in Bill Montaigne’s car. On the way they stopped for Ethel. The Wilkies were out, but they collected Hartley and the Millinghams and the Russells and the Williamses, and, a party of a dozen in their cars, they drove over to the old Wilkinson place.

A colored maid in a white cap and apron opened the door. Jimmy wasn’t at home, but he was expected momentarily.

“Let’s wait for him,” Mrs. Montaigne suggested.

They filed into Jimmy’s living room and found chairs and examined Jimmy’s stage setting.

There was an ancient spinning wheel beside the fireplace; a pair of whale-oil lamps on the mantel; and a sea chest in the corner.

Ann Laidlaw pointed to the open doorway.

“Look at that,” she said. In the room beyond was the big easel that Jimmy had brought with him from the Thorpe house. Beside it, on a stand, lay a palette laden with all the colors that come in tubes. On a chair lay Jimmy’s smock. By these simple devices the Wilkinson back parlor had become a painter’s studio.

“You know,” said Bill Montaigne, “I think he’s clever. We’ve got to hand it to him.”

“I’ll call him clever if he can undo the harm he’s done,” said Hartley. “Can’t draw,” he muttered. “Never will be able to draw.”

Jimmy Dowling dashed in a few minutes later.

“Hello,” he said. “Won’t you all have tea?”

“We’ve come,” said Hartley, “to hear what you’ve got to say for yourself — and not for any tea.”

“Oh, come,” said Jimmy, “do have tea!” He shot out of the living-room into the kitchen to consult the maid.

“Now,” he said, when he had given his orders, “what can I do for you?”

Steve cleared his throat.

“You can tell us where we can get places to live — that we can afford,” he said. “None of us can stand the pace in this town since you began to advertise it.”

Jimmy leaned against the mantel and smiled engagingly at the dozen who confronted him. Steve observed that he was not the same Jimmy who had knocked at the studio door a few months back. He was no longer an unhappy boy looking for sympathy. He was a man who had found himself. And it wasn’t the new suit he was wearing, either.

“I’ve been thinking about your problem,” Jimmy said. “In fact I’ve found the answer.”

“What is it?” barked Joe Hartley.

“Old Port Orchard,” said Jimmy. He paused a moment. They must all know Old Port Orchard.

“Go on, son,” said Hartley. “What about Old Port Orchard?”

“Old Port Orchard,” Jimmy said impressively, “is probably the loveliest old village in New England. It’s thirty miles farther from New York. But it’s on the Sound, and it’s quite unspoiled. Real estate values are lower than they were in Deep Harbor before the — er — present boom.’

“Thirty miles farther!” said Bill Montaigne.

’What’s thirty miles to you?” Jimmy asked. “You don’t go to New York more than once a month.”

“But — “ Steve began.

“In my opinion,” Jimmy interrupted, “Old Port Orchard is a more charming place than Deep Harbor ever was. And if you’ll appoint a committee of one to go up there with me and look the place over I’ll undertake to manage the business end of it so quietly that there won’t be a tremendous jump in values.”

The white-capped maid brought in tea then, and Jimmy answered questions, and within an hour it had been agreed to send Ann Laidlaw with him to see Old Port Orchard. Only Hartley was unappeased.

“Look here, Dowling,” he growled, “what are you going to do? Are you going to settle in Old Port Orchard and pull this same stunt over again?”

“No,” said Jimmy Dowling. “I’m going to Massachusetts as soon as I’ve cleaned up here. I hesitate to mention it in this company, but there’s a man there who thinks he can make a painter out of me. He admits I can’t draw, but — well, he likes my color. Anyhow, whether I can paint or not I’m going to paint. I’ve got money enough to last me for two or three years. And when it’s gone I’ll make some more.”

It was Steve Laidlaw who asked the last question. He hung back as the rest said good-by to Jimmy Dowling, in order to ask it.

“Jimmy,” he said, “you told me that day you came to my studio how you hated your father’s business. What is his line?”

“Real estate,” said Jimmy Dowling.

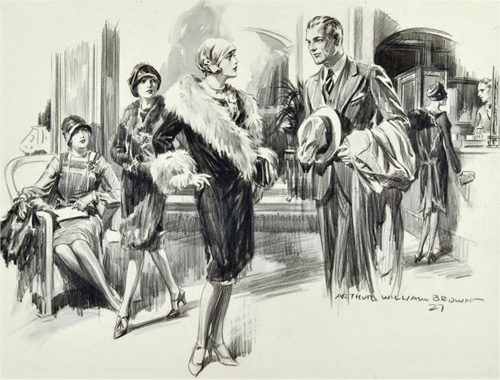

Illustrations by Leslie L. Benson/ SEPS

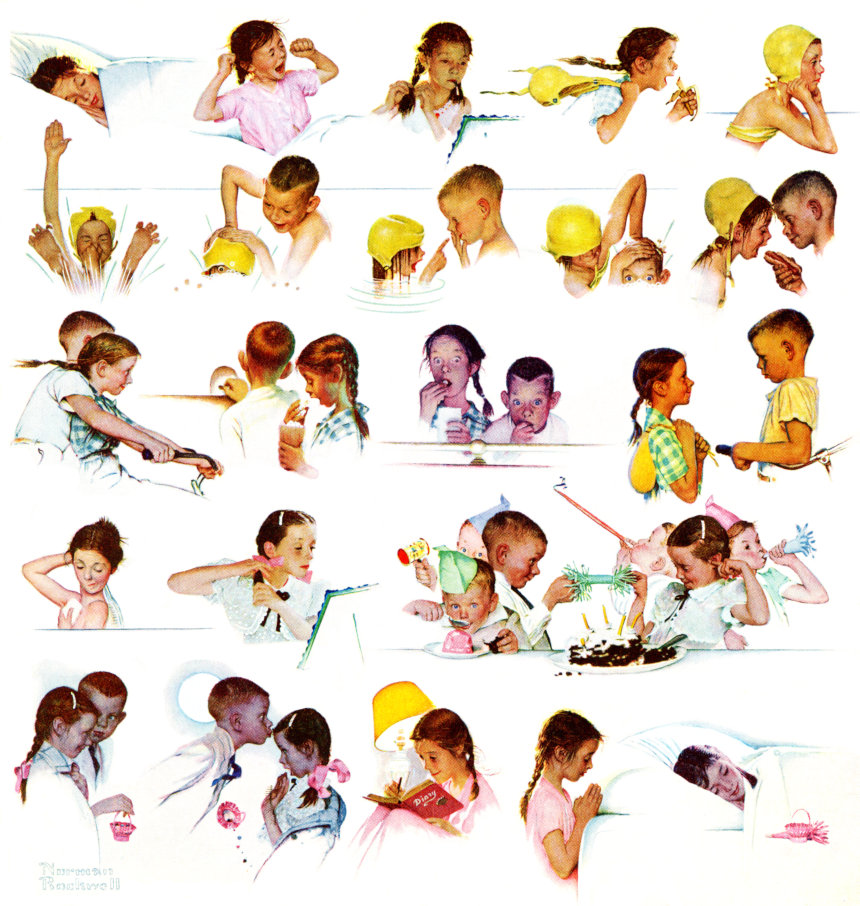

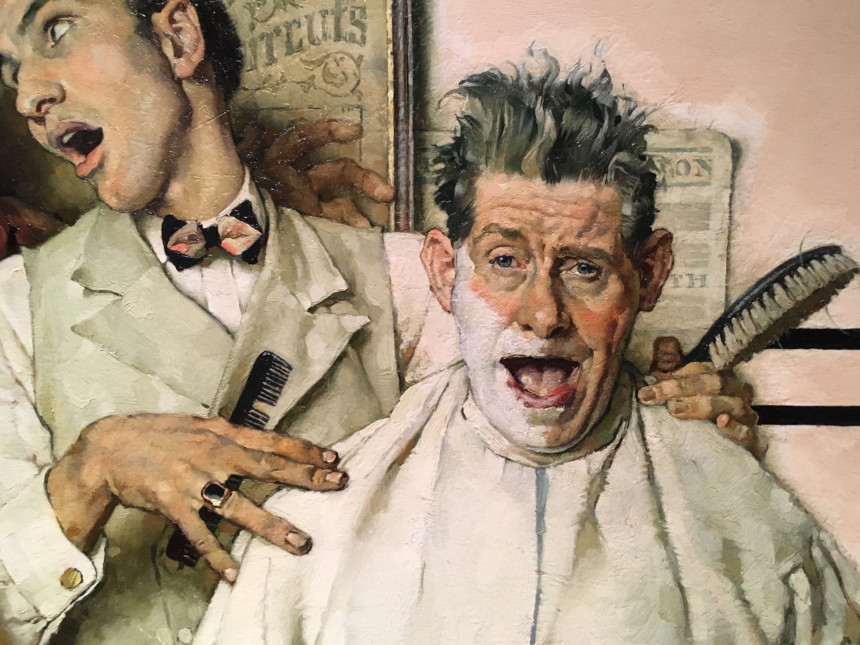

Rockwell Video Minute: Cousin Reginald

See all of the videos in our Rockwell Video Minute series.

Featured image: Norman Rockwell / SEPS

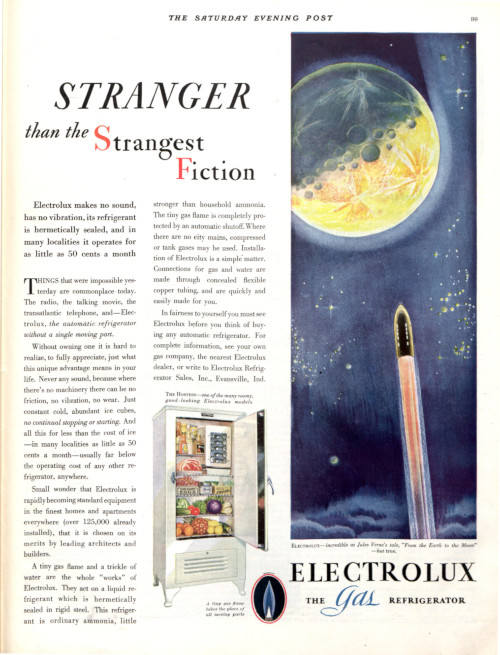

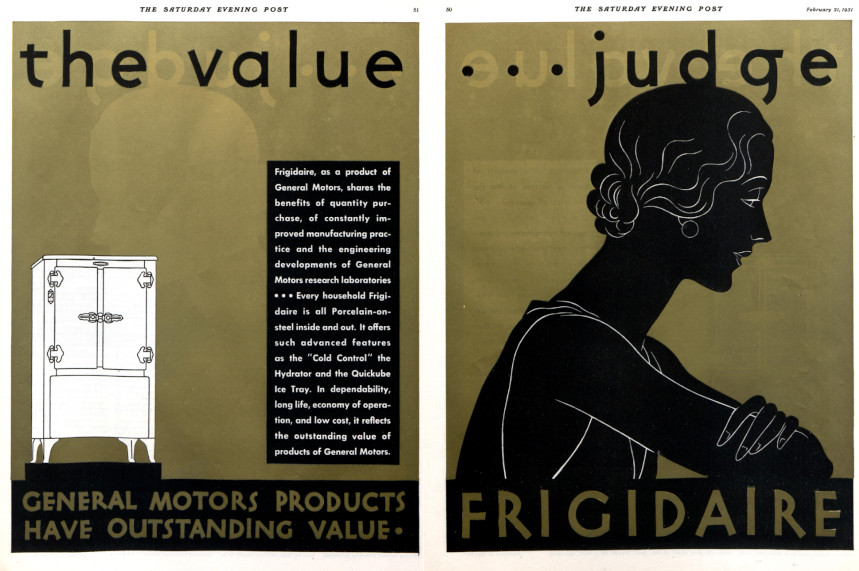

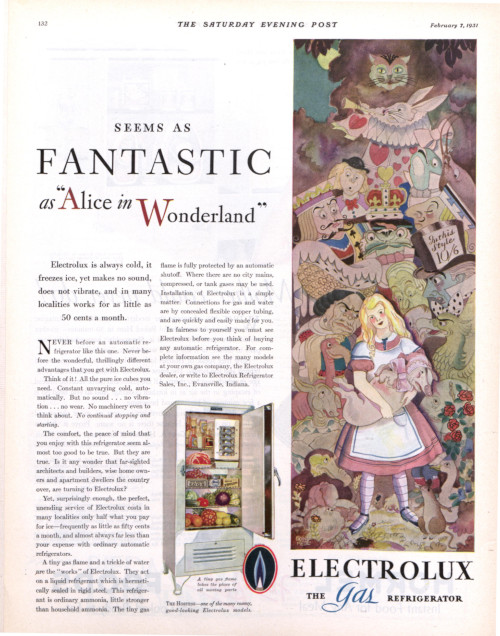

The Art of the Post: The Art of…the Refrigerator?

Read all of art critic David Apatoff’s columns here.

The first practical refrigerators were invented a century ago and instantly transformed American domestic life. The Saturday Evening Post was flooded with advertisements for the strange new devices. Illustrators were hired to help the public imagine how refrigerators would fit into a home and envision the role they could play. Some were more successful than others.

Inventor Fred Wolf of Ft. Wayne, Indiana started the rush in 1913, with the announcement of the first refrigerator for home and domestic use. A year later, an engineer in Detroit jumped in with his suggestion for an electric refrigerator, the predecessor of the famous Kelvinator. By 1918, the demand for the new invention had become clear, and the Frigidaire company was founded to mass produce refrigerators.

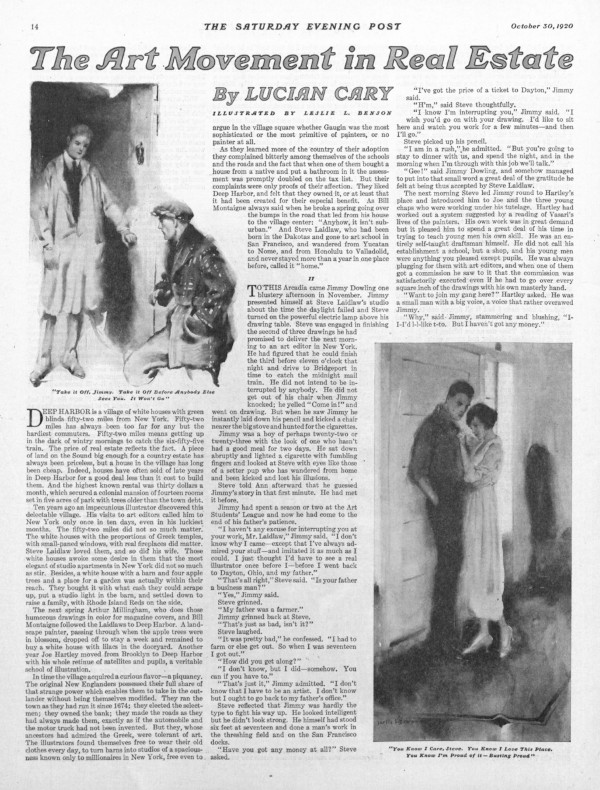

Rival companies popped up, each trying to outdo the others with features they thought the public might like. For example, Kelvinator touted the first refrigerator with an automatic control. Electrolux offered what it called the first “absorption refrigerator.” Inventors and engineers battled over the science. Here is a two-page ad from the Post bragging about the factory where the “hermetically sealed refrigerating unit” is contained within the “steel monitor top.”

But it took art, not science, to humanize the strange new invention. Refrigerator companies faced a big challenge selling the new invention to everyday Americans; in 1922 a refrigerator could cost over $700 while a new car (the Model T Ford) cost only $450. The public wouldn’t buy refrigerators without a vision for how they would fit into the American lifestyle.

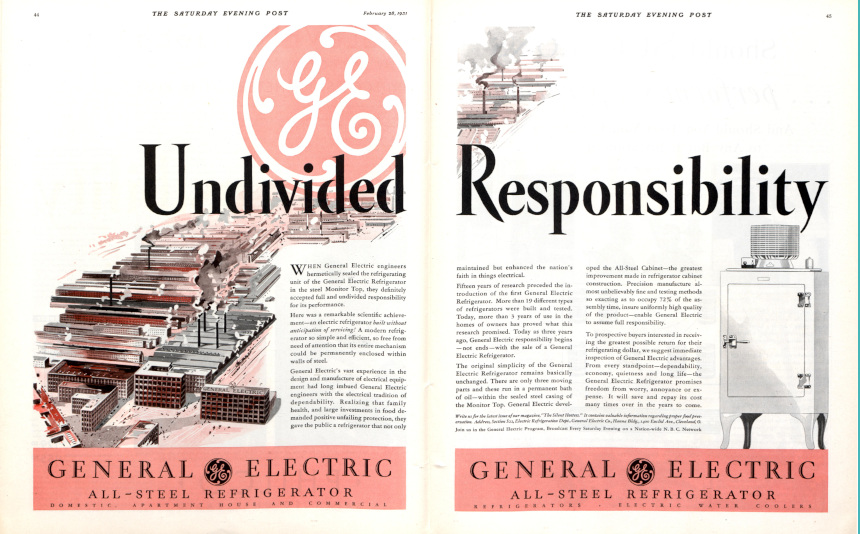

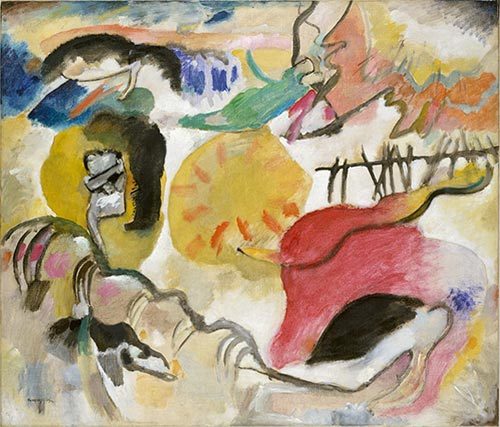

Here we see a 1929 painting by Walter Biggs of a high-class social event:

The men are wearing tuxedos and the women dressed in fashionable gowns. They smile as they exchange witty banter about cultural events. But the real star of the party—and the whole reason for the painting—is that brand new refrigerator in the far right hand corner.

Right smack dab in the center of the painting is the modern miracle… glasses filled with ice! Ice was readily available for guests for the first time with the invention of the refrigerator. Today we wouldn’t think of keeping our refrigerator in the middle of our dining room with the guests, but this picture tells us that it was a mark of prestige.

Next, this enterprising artist tries to portray the refrigerator as a springboard to romance. (Hah! Good luck with that!)

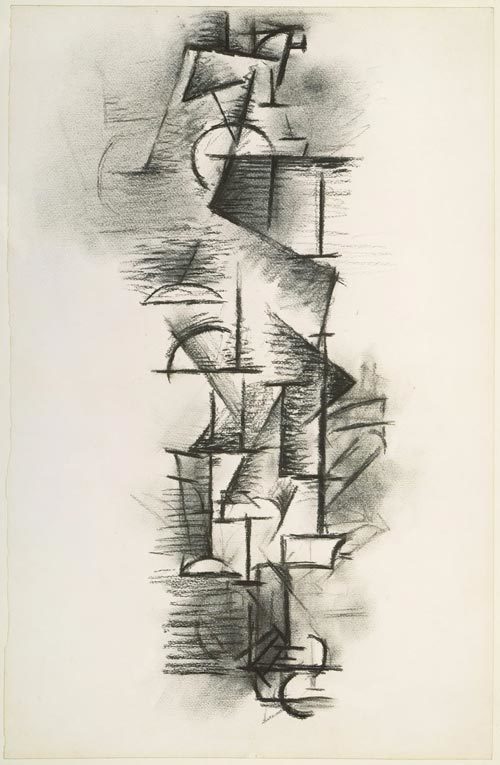

Another artist felt he could make the new invention popular with a “science fiction” approach:

This artist does his best to make a white metal cube look stylish by making it a tiny element in a large, black and gold art deco picture. Note that Al Dorne’s harried, overworked housewife has become an elegant young woman of leisure in an evening gown.

There were even illustrations for consumers who felt that a refrigerator was “like magic.”

Today many of these approaches seem silly to us, but in the beginning before the identity of the refrigerator had been firmly established, artists could let their imaginations run wild.

It always takes a while for people to figure out the proper role for the new invention; when trains first arrived on the scene, they were noisy and frightening. They spooked horses and polluted the environment with smoke and cinders. But artists and musicians and storytellers began to humanize the new machine, singing folk songs and telling tales, and pretty soon we welcomed trains into our cultural heritage.

We rely upon the artistic imagination to help us view our strange new inventions and assimilate them into our natural world. Nothing like the refrigerator had ever existed before, so there were no precedents for artists to rely on. Some of the earlier efforts make us laugh today, but eventually illustrators found their footing.

Featured image: Courtesy of the Kelly Collection of American Illustration

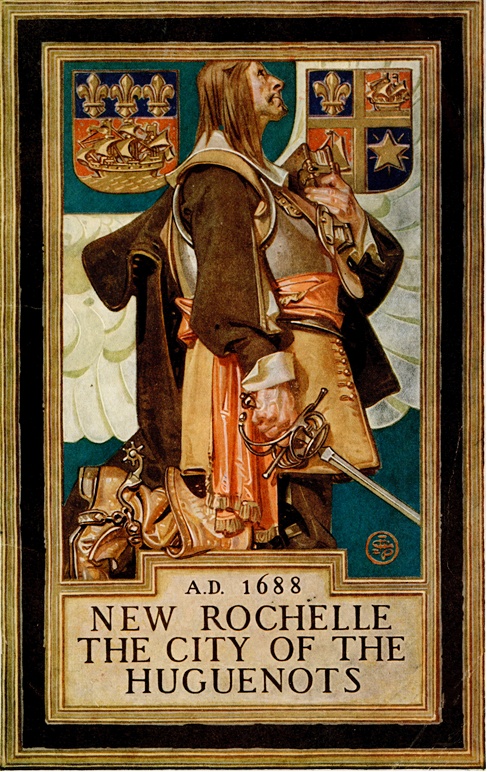

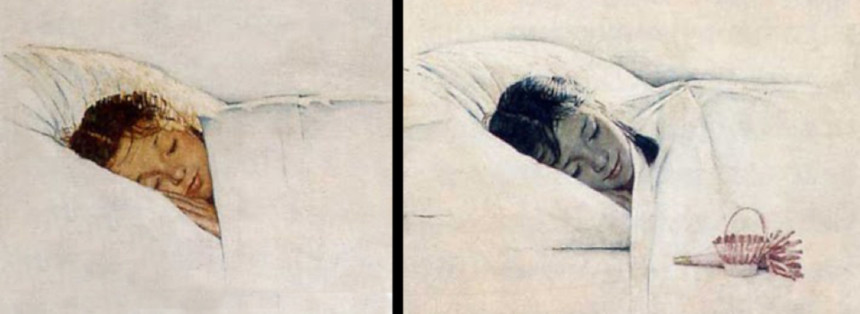

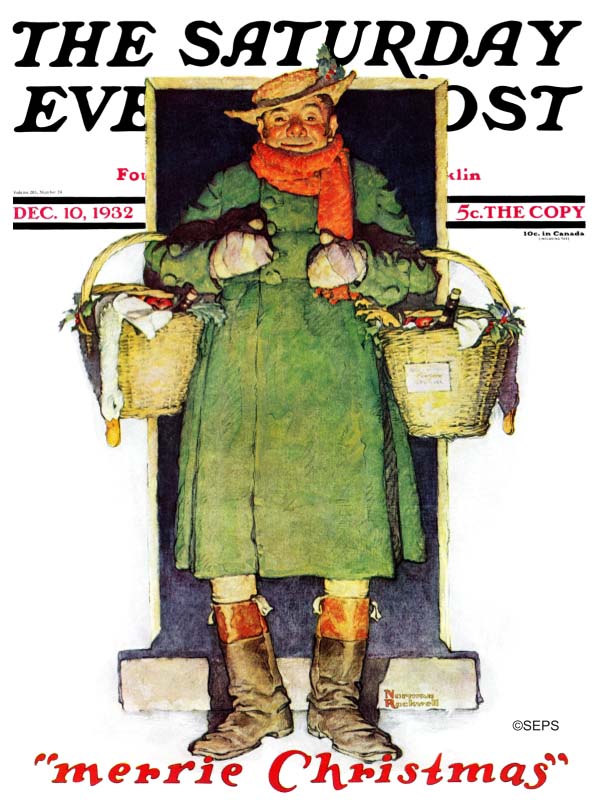

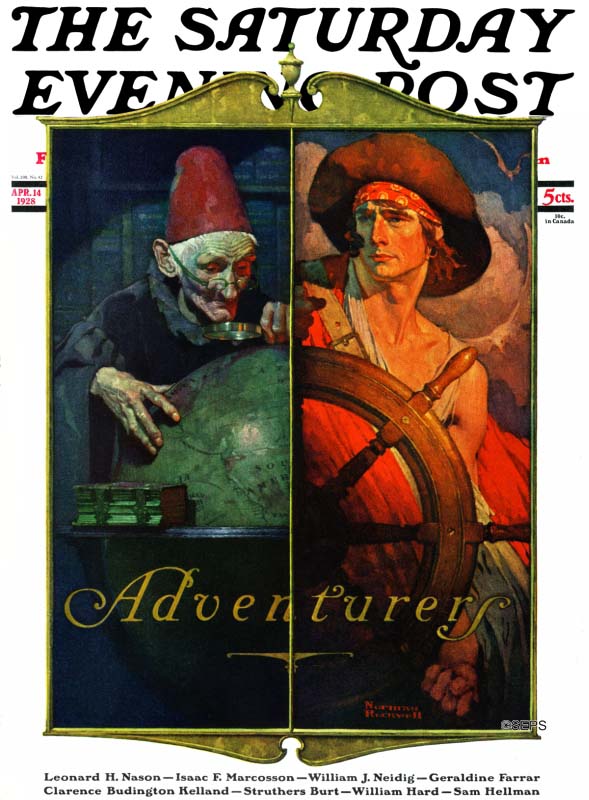

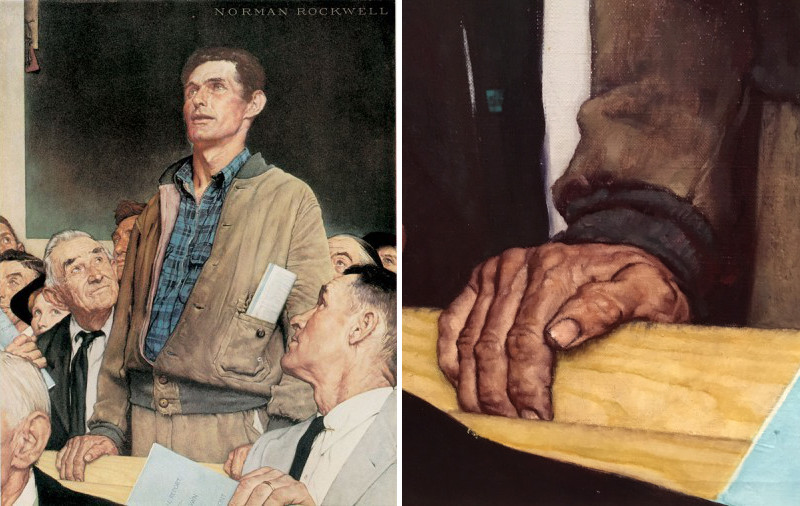

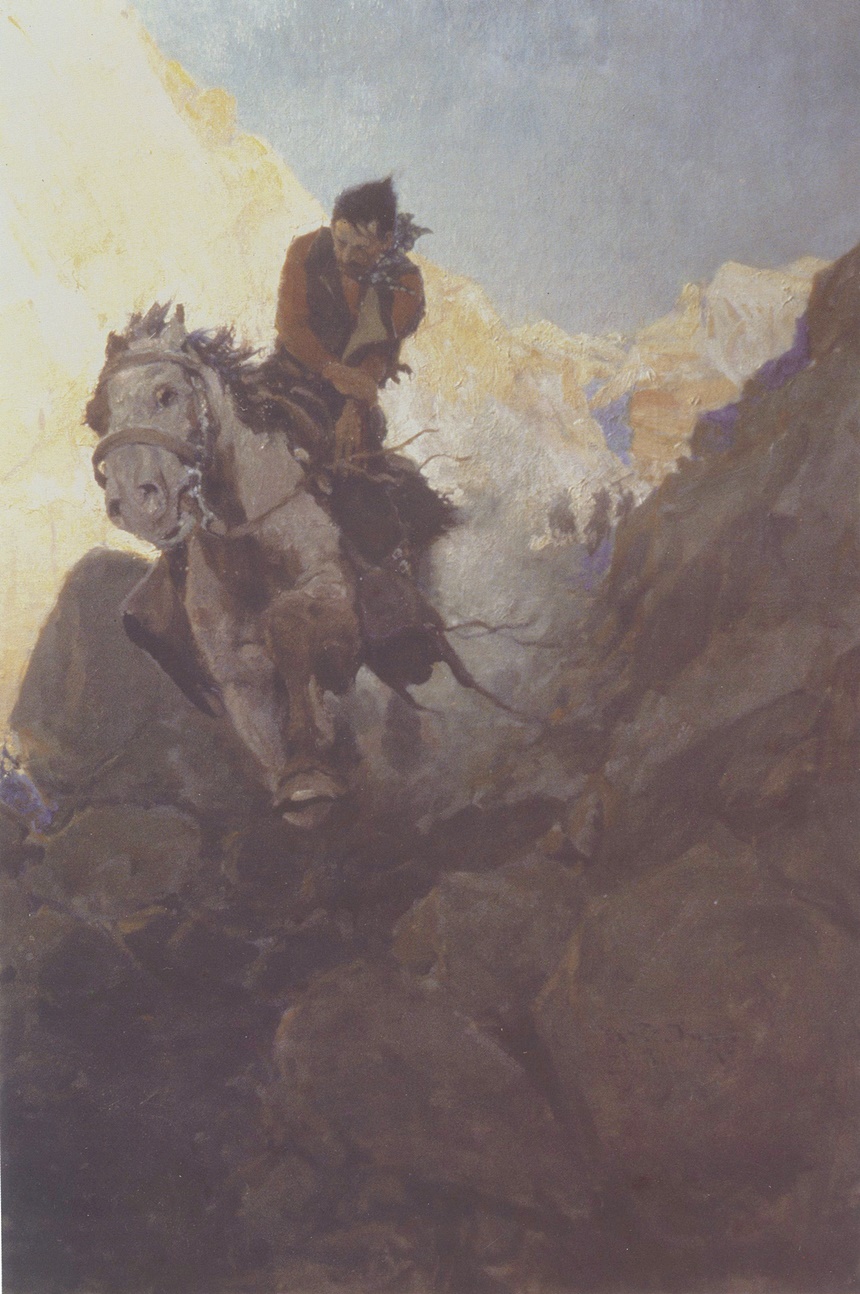

The Art of the Post: Norman Rockwell’s Most Important Art Lesson

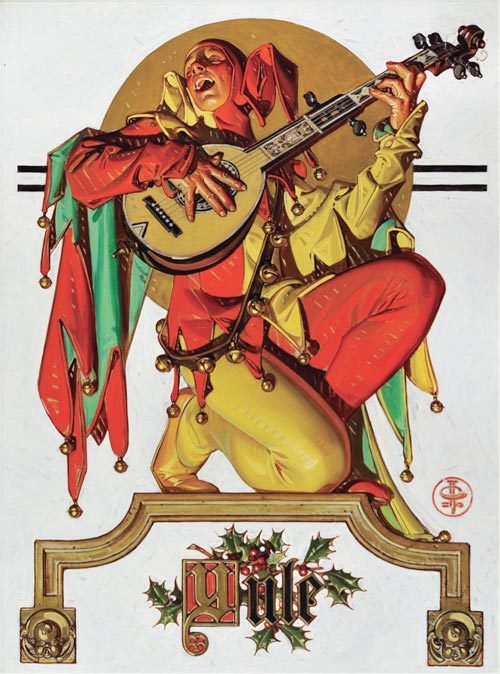

Read all of art critic David Apatoff’s columns here.

When Norman Rockwell was a young art student, he idolized Joseph Leyendecker, who he called “the most famous illustrator in America.” Leyendecker was a cover artist for The Saturday Evening Post, and painted more than 300 covers between 1903 and 1943. Rockwell dreamed of becoming a cover artist too, but didn’t know how he could ever paint as well as the great Leyendecker.

In his autobiography, Rockwell recounted how he spied on Leyendecker, trying to learn his artistic secrets:

I’d followed him around town just to see how he acted…I’d ask the models what Mr. Leyendecker did when he was painting. Did he stand up or sit down? Did he talk to the models? What kind of brushes did he use? Did he use Winsor & Newton paints?

Unfortunately, none of this information seemed to make Rockwell a better painter.

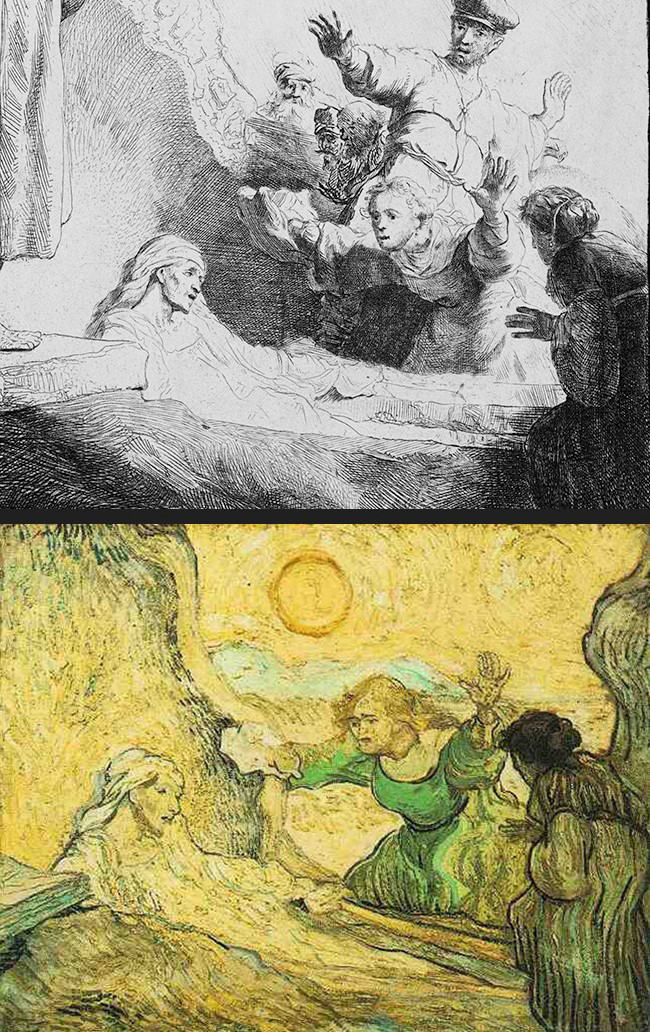

A few years later, Rockwell finally got to visit Leyendecker in his studio and watched first-hand the master working on a painting. It turned out that Leyendecker’s secret had nothing to do with his brand of brushes or paint. Rockwell recalled:

New Rochelle published a brochure illustrated with reproductions of paintings by all the famous artists who lived in the town. Joe worked on his painting for months and months, starting it over five or six times. I thought he’d never finish it.

The painting that Rockwell saw on Leyendecker’s easel was beautiful, with many fine touches.

The painting was 95 percent finished and the client would have been happy to pay for it. All Leyendecker needed to do was finish this hand and a few other touches.

Yet, Leyendecker remained unsatisfied. The painting didn’t meet his high personal standards.

Rather than correct the parts he wanted to improve, Leyendecker set the entire painting aside and started all over again, searching for the exact image he envisioned.

Later, when Rockwell saw the final version published by New Rochelle, it looked like this:

This gave young Rockwell a lot to think about: Leyendecker’s first version was perfectly acceptable; it just wasn’t 100 percent what it could have been. Leyendecker seemed to spend a lot of time starting over in search of that elusive missing five percent.

Leyendecker’s high standards made Rockwell nervous about showing his own work to the master. Rockwell wrote, “You never asked Joe…what he thought of your painting unless you wanted a real critique; he thought nothing of starting a picture over again.”

But when it was Rockwell’s turn to become a professional illustrator, it seems he had learned the lesson. He painted “100%” in gold at the top of his easel to remind himself never to give anything less. That philosophy kept Rockwell at his easel seven days a week painting countless studies in order to get the details right. If he’d been willing to accept 95 percent, Rockwell could’ve worked faster, made more money and spent more time with his family. But he learned the lesson of Leyendecker, and that’s why people still remember him and admire his work today.

Featured image: Painting by J.C. Leyendecker. Photo courtesy of David Apatoff

“Home-Brew” by Grace Sartwell Mason

With more than 80 short stories and eight novels, Grace Sartwell Mason’s thematically diverse work found many publications in the period before and after World War I. Though her fiction and criticism has slipped through the cracks of familiarity over the years, her story “Home-Brew,” about the secretive and adventurous family of a budding New York writer, was an O. Henry Award finalist.

Published on August 18, 1923

Content Warning: Racial slurs

“Of course, they’re all dears, my family,” said Alyse; “but as fiction material there is nothing to them; no drama, you know; no color; just nice, ordinary, unimaginative dears. They’re utterly unstimulating. That’s why I can’t live at home, and create. They don’t understand it, poor dears; but what could I possibly find to write about at home?”

She crushed down upon her hair, with its Russian bob, a sad-colored hat of hand-woven stuff, and locked the door of a somewhat crumby room over the Rossetti Hand-Loom Shop, where she worked half time for a half living. A secondhand typewriter accounted for the other half; or, to be quite truthful, for a fraction of the other half. For her father, plain George Todd, helped out when the typewriter failed to provide.

She then betook herself on somewhat reluctant feet to the nearest Subway. For this was her evening at home with her unstimulating family; and though she was fond of them all, her predominating feeling for them was a mixture of amusement, tender tolerance and boredom. Moreover, they lived in Harlem, which was a deplorable wilderness, utterly lacking in atmosphere and a long, long way from the neighborhood of the hand-loom shop.

In the Subway, miraculously impelled through the bowels of the earth, Alyse — or Alice, as she had been christened — refrained from looking at the faces opposite her. The Subway does something curious to faces. It seems to drain all life out of them; it strips from them their defensive masks and exposes the deep and expressive scars of existence. A secret and hidden soul comes out in each Subway face. But Alyse averted her eyes.

“Dear me,” she sighed, “how dull they are! Isn’t there any beauty left in the world?”

Her father and his chum, Wally, were just ahead of her as she came up from the Subway depths. They were wending their way to their respective homes, having come up from downtown together, as was their invariable custom. Alyse gazed at their middle-aged backs without seeing anything unusual about them. Just two plodding men, getting tubby about the waist, with evening papers under their arms, walking along, not saying much. But when they reached George Todd’s door they would look at each other, and the passerby might well have stopped and taken off his hat, as before something rare and soul-satisfying. For here was perfect peace in friendship.

But all they said was: “S’long. See you tonight, ol’ hoss.” Or, “See you t’morrow mornin’, Georgie.”

Alyse had heard the tale of her father’s miraculous reunion with Wally so many times that it meant nothing to her. It seemed that as boys they had lived within two doors of each other in a small New England town, and they had been inseparable. First thing in the morning and last thing at night they were whistling outside each other’s windows; they owned a dog in common; and when George had scarlet fever, Wally nearly died from anxiety. Then, at sixteen, life had borne them in different directions. Wally drifted finally to Alaska and George got a job in New York. For a time they corresponded, but after a while letters began to come back to George marked Not Found, and then in a roundabout way he heard of Wally’s death.

Although George Todd was happily married, with a growing family, he admitted that the world would never seem quite the same to him with Wally out of it. Then came the happening that convinced him there are mysterious and unexplainable things in the world, say what you like. He was coming home from work one night, walking from the Subway rather more slowly than usual and enjoying the spring twilight, when in some strange way his heart stirred. He remembered how on evenings such as this he and Wally used to play a game in which one tossed a ball over the house to the other and gave a peculiar call. The middle-aged George declared that all of a sudden he could hear this call, and wanting to fix it in his memory, he endeavored to imitate it by whistling its rather melancholy intervals.

And at his whistle a man walking in front of him suddenly whirled and stared at him. It was Wally — Wally, with a newspaper in his pocket and a bundle of shirts from the laundry under his arm. He had been living within half a block of George for two years.

When her father told this story to Alyse he always at this point gave her an affectionate poke.

“Now there’s a story for you, Allie. You write up about Wally being washed out to sea and given up for dead and working his way around the world, and finally settling down in Harlem right next door to his old chum. And that about the whistle. What was it made me think of that old call?”

Alyse would explain that it was coincidence, and coincidence was the lowest form of literary life. She was patient about it, but there was nothing stimulating to her creative imagination in Wally and that come-and-find-me voice he had listened to half his life. Still less was she stimulated by her father, George Todd, owner of a feed and grain business of the most eccentric instability. He was a dear, and she loved him; but she hoped as they all sat down to supper that he wouldn’t begin to joke her about her work or offer her the plot for a story.

It was a spring evening and the dining room windows were open to the two lilac bushes which Alyse’s mother had nursed for years in the narrow, sooty backyard. The room was filled with an unreal light, as if the air was full of golden pollen dust. And something else, invisible and palpitant, was in the air of the homely room, something not to be seen but only sensed. Some intense preoccupation a sympathetic eye could have noted in three of the faces around the table.

“Well, well, we’re all dressed up tonight,” said George Todd, unfolding his napkin. “Look at Miggsy, Allie. Won’t she knock somebody’s eye out tonight?”

Alyse looked at her young sister, Mildred, aged sixteen. Mildred blushed, fidgeted, pouted entreatingly at her father. She was a thin little beauty, with a soft cloud of corn-silk hair about her face. In her red mouth desire and wistfulness mingled. Tonight her eyes were stretched and brilliant. She twitched at the table silver and appeared to have no appetite.

“Eat your spinach, dearie.” Her mother’s eyes brooded over her tenderly. “I thought you liked it creamed.”

“I do, but — Goodness, mother, is that clock right? I must fly!”

“But there’s chocolate pudding for dessert, dear.”

“Now, Miggs, finish your dinner. Why be so fidgety?”

Mildred looked in desperation from her father to her mother.

“But I don’t want any dinner, please! I — I have to be there early. Please let me go now, mother.”

She danced from one foot to the other, the secret excitement in her eyes threatening to change to anger. She had spent most of the time since she came home from school that afternoon in front of her mirror, and she was now exquisitely polished, powdered and perfumed. From under the fluff of hair over each ear an earring of blue to match her eyes dangled.

Alyse disapproved of the earrings and of the general effect of Milly tonight. She made a mental note to speak to her mother about letting the child go out so many evenings. But beyond the earrings and the general overstrung and overdressed effect she did not penetrate. She made no attempt to interpret the secret excitement in her young sister’s eyes. The affairs of a girl of sixteen were too inane and foolish to be taken seriously.

At the table when Milly had gone flying up the stairs there remained Alyse, her father and mother, Eddie, twenty-one, and Aunt Jude. Alyse glanced around the table and suppressed a sigh. The monotony of the lives of her family sometimes oppressed her. Take her mother, for instance. She seldom went outside the house except to church or to an occasional motion picture with Wally and George. All day she did housework or looked after Grandma Todd when Aunt Jude was at work. She did not have a cook because of a queer passion for feeding her family herself. But when she had them all there in front of her, ranged around the long table, and she had put onto their plates the well-cooked, savory dishes they liked, she would sit, eating little herself, looking from one to the other with her slightly anxious, tender glances, while gradually an expression of peace and satisfaction stole into her face; and Alyse wondered what her mother was getting out of life.

Take Eddie, also. No one, except perhaps his mother in odd moments, ever got a peep-in at Eddie’s thoughts. Alyse was of the opinion that he didn’t have any. There had been a time when she had tried to bring Eddie out by coaxing him down to her rooms over the hand-loom shop and introducing him to some of the girls she knew. But those clever and voluble maidens had abashed Eddie unspeakably, and Alyse had let him lapse back into his own plodding life. He apparently had no imagination. Soon after he left high school he had gone to work for a seed house downtown — George Todd badly needing help that year with the family expenses — and there he still was. Alyse hadn’t the slightest idea what were his amusements. Saturday and Sunday afternoons he generally disappeared, and when asked what he had been doing, he had been to a ball game or just taking a stroll around. He subscribed to a marine journal, which seemed strange reading for a packer in a seed house.

Take Eddie, also. No one, except perhaps his mother in odd moments, ever got a peep-in at Eddie’s thoughts. Alyse was of the opinion that he didn’t have any. There had been a time when she had tried to bring Eddie out by coaxing him down to her rooms over the hand-loom shop and introducing him to some of the girls she knew. But those clever and voluble maidens had abashed Eddie unspeakably, and Alyse had let him lapse back into his own plodding life. He apparently had no imagination. Soon after he left high school he had gone to work for a seed house downtown — George Todd badly needing help that year with the family expenses — and there he still was. Alyse hadn’t the slightest idea what were his amusements. Saturday and Sunday afternoons he generally disappeared, and when asked what he had been doing, he had been to a ball game or just taking a stroll around. He subscribed to a marine journal, which seemed strange reading for a packer in a seed house.

And there was Aunt Jude. Really, when you considered everything, what had Aunt Jude to live for?

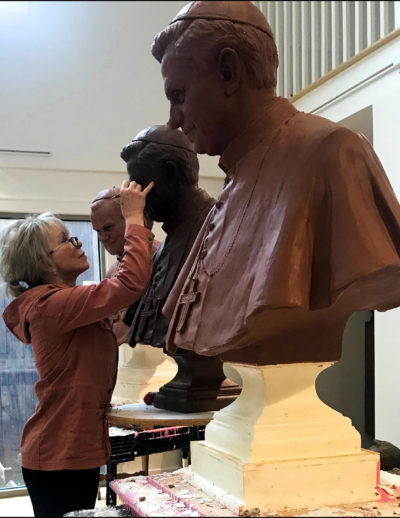

Judith Todd was at that moment preparing a tray for Grandma Todd, who was having one of her faint spells and declined to come down to supper. With her long, slender fingers moving deftly, Judith made the tray inviting with the china she had bought especially for it. She had hurried her own supper so as to have plenty of time for the tray, and she moved from the table to the sideboard with the air of detached and ironic competence she sometimes wore when she was, as Alyse said, spoiling Grandma Todd. She was George Todd’s younger sister, thirty-eight, a spinster with the reputation of having been in her youth very high-spirited, adventure-loving, and moreover with a streak of queerness about her. As, for instance, her ambition to be a sculptor. In those days and in the Todds’ native village a girl might as becomingly have wanted to be a circus rider. It was said there had been some stormy scenes over days wasted in the attic with messy clay. But finally life itself had put a bit between her teeth — life and her mother’s well-timed heart attacks. Her father had failed in business and died, George had married early, and the brunt of taking care of her mother had fallen to Judith.

After a while she had brought her mother to George’s house, which helped George out with expenses and enabled Judith to make a living for herself. It was the nature of her job that convinced Alyse there couldn’t be anything in that old story about Aunt Jude’s having wanted to be an artist. It was such an absurd job. She worked for one of those concerns that produce novelties — favors, table decorations, boudoir dolls — designing many of these silly fripperies, often making them with her own hands. She had remarkable hands.

If she had an ounce of talent, Alyse decided, how could Aunt Jude go on, year after year, squandering herself on these silly and often grotesque objects? Alyse felt that it would have killed her to have so degraded her talent.

But Judith actually appeared to get a certain amount of fun out of the dreadful things. She would bring home samples of her handicraft and bedeck the supper table with tiny fat dolls in wedding veils, droll birds and beasts in colored wax, and so on. And in one of her high moods she could set the family to laughing with a single tweak at one of these grotesqueries. On these occasions a gay and malicious sparkle would come into her dark eyes, and her laugh would be high and reckless, rather like a person who has taken a stiff drink to ease up an ancient misery.

Two evenings a week she went out, no one knew where. Alyse had seen her once at the opera, leaning far out from the highest gallery, a frown between her brows, seeming to watch rather than to listen, with a wild brightness in her dark eyes. The general impression of the family was that these regular evenings away from home had something to do with her work. On these particular evenings there was always a breathless air about her. She would hasten in from the street, and as she climbed the stairs to her mother’s room her face would stiffen as if for conflict. For Grandma Todd resented these evenings.

“Traipsin’ off,” she called it. “Lord knows where. Something will happen to you, coming home alone after ten o’clock. I don’t think you’d better go out tonight, Judith. My heart has been fluttering this afternoon. If I have to lie here worrying all evening I shall probably have a bad spell.”

And then into her daughter’s face would come the expression of a person swimming painfully against the tide. Love and pity had overcome her at every turn of her life, until at last she had almost nothing of herself left, except her freedom for these two evenings. As if the call of them was more imperative even than her long habit of abnegation, she fought for them with a sort of desperation.