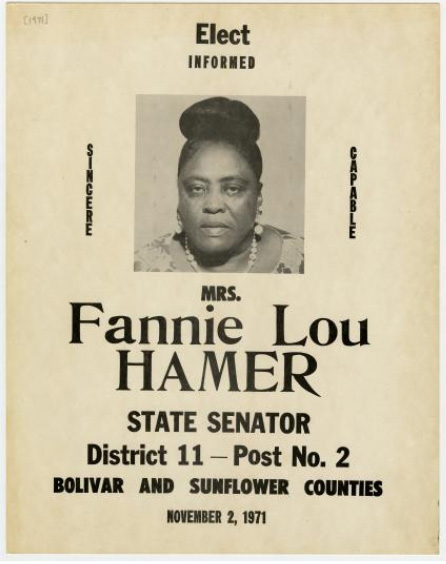

Fannie Lou Hamer’s War on Voter Suppression

Lyndon B. Johnson was distressed a few days before the start of the 1964 Democratic National Convention. In a presentation to the party’s Credentials Committee in an Atlantic City hotel ballroom, a Black Mississippi woman named Fannie Lou Hamer was giving a disturbing account of her various past attempts to exercise her right to vote. She was “sick and tired of being sick and tired.”

Hamer, then 46 years old, had been the youngest of 20 children in her family, leaving school in sixth grade to work on Mississippi plantations. She had been poor her entire life, and suffered from polio as a young girl. Just three years earlier, she had been sterilized against her will while hospitalized for a minor surgery. But her address to the 108 committee members that day recounted, in sickening detail, numerous instances of violent institutional repression that had prohibited Hamer from participating in her country’s — and the Democratic Party’s — democratic process.

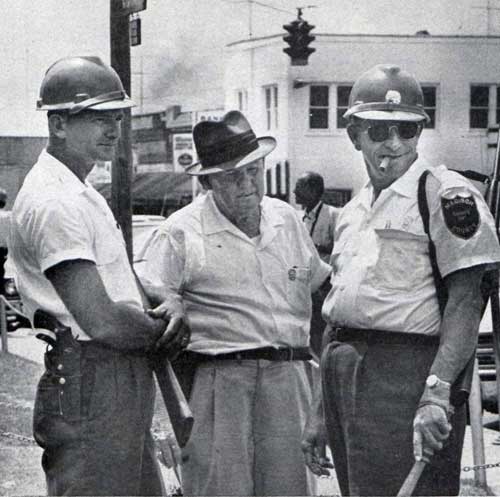

She first failed the arcane and discriminatory literacy test that was administered to African Americans in 1962. Then, she was on a busload of hopeful Black voters that was pulled over for being the wrong color (too yellow). Then, the plantation owner kicked her off the land she sharecropped (for attempting to register to vote). Then, in 1963, she was arrested with several others after attending a voter registration workshop. While in jail, she was brutally beaten with a blackjack by other prisoners at the orders of a state trooper who told them to, according to this magazine, “Make the bitch wish she was dead.”

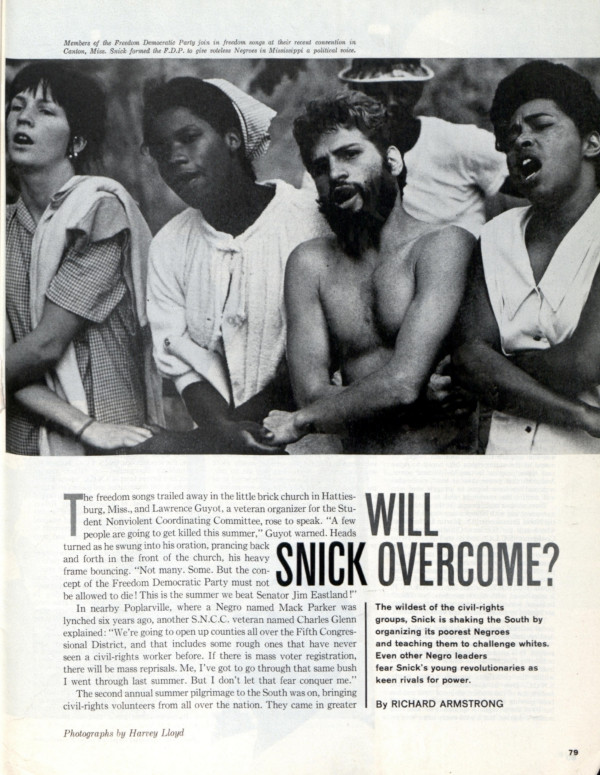

At the Democratic Convention, Hamer was speaking on behalf of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, a grassroots political project that aimed to replace the state’s elected delegation on the premise that it was illegally selected with a segregated vote — a “white primary.” Less than seven percent of eligible Black adults were registered to vote in Mississippi in 1964. With the cooperation of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC or “Snick”), NAACP, Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and the Congress of Racial Equality, activists in the South organized tens of thousands of mostly Black, poor and working-class people in a precinct-level effort to subvert the all-white Democratic stronghold in the state.

President Johnson worried that the MFDP — and a potential interracial delegation — would alienate the South’s white Democratic voters, sending them into the arms of the Republicans. During Hamer’s speech, he called an impromptu press conference, leading many to think he was about to announce his running mate. Instead, he gave a commemoration of President Kennedy, who had been assassinated nine months earlier. The television networks still played Hamer’s speech, though, during their primetime broadcasts. Their viewers saw the poor Black sharecropper’s impassioned indictment of her country: “Is this America, the land of the free and the home of the brave, where we have to sleep with our telephones off the hooks because our lives be threatened daily, because we want to live as decent human beings, in America?”

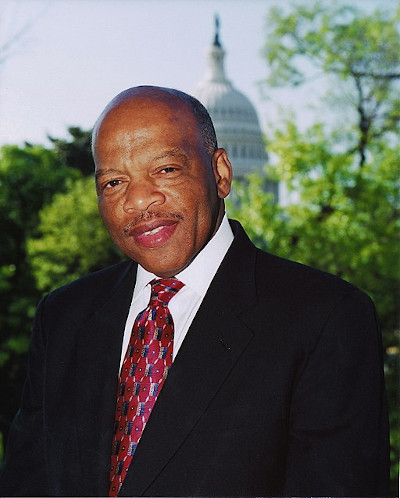

Hamer’s testimony was an uncomfortable dose of reality for liberal America. Even today, her story teaches largely unexamined lessons regarding the background work of the civil rights movement and its many proponents. As scholar Maegan Parker Brooks wrote in her recent biography of Hamer, “The life story of a disabled, impoverished, middle-aged black woman from the rural Mississippi Delta challenges widespread perceptions of who participated in — as well as how they influenced — mid-twentieth century movements for social, political, and economic change.” Hamer is not a household name like Martin Luther King, Jr. or John Lewis, but her role in this transformational period of American history shows us what was at stake, and indeed still is.

Hamer didn’t appear at the 1964 Democratic National Convention out of thin air. Along with three other Black candidates in the state, she ran a primary campaign against the longtime Mississippi representative Jamie Whitten. The Freedom Democrats had been working since the previous fall to both register Black Mississippians and hold straw votes in their own “freedom-registration books” to show what electoral participation could look like in the state where African Americans made up 42 percent of the population. That summer, a profile of Hamer in The Nation posited that “The wide range of Negro participation will show that the problem in Mississippi is not Negro apathy, but discrimination and fear of physical and economic reprisals for attempting to register.”

During the Freedom Summer of 1964, the civil rights groups that made up the Council of Federated Organizations undertook a statewide organizing effort to account for Black non-voters and register as many as possible. They also established Freedom Schools, community centers, and a Freedom Labor Union. At the heart of this undertaking was the oversized contribution of SNCC, the activist group Hamer had worked with diligently since attending a mass meeting in 1962. Hamer traveled around the state, stirring Black audiences with speeches that motivated them to act for their own liberation. (“It’s a shame before God that people will let hate not only destroy us, but it will destroy them. Because a house divided against itself cannot stand and today America is divided against itself because they don’t want us to have even the ballot here in Mississippi.”) At the same time, SNCC’s army of volunteers — largely white college students from the North — were moving around Mississippi organizing for participatory democracy at every level.

In 1965, this magazine covered the student group (“Will Snick Overcome?”), pointing out the markedly more radical approach SNCC employed compared to a group like the NAACP. Arising from the sit-ins of 1960, SNCC was an early opponent of the Vietnam War and decidedly non-hierarchical. While it claimed manpower from the country’s college students, SNCC aimed to cultivate leadership at the community level in its campaigns. The Post recognized this unique tactic of SNCC’s “shock troops,” even if it seemed tedious: “The whole concept of building a political force out of tenant farmers, slum-dwellers and the unemployed is a radical departure from American political norms.”

In response to claims that communists and Marxists — perhaps even foreign ones — were stirring up all of the trouble in the South, Hamer gave a simple response in a speech at a mass meeting in 1964: “People will go different places and say, ‘The Negroes, until the outside agitators came in, was satisfied.’ But I’ve been dissatisfied ever since I was six years old.” Hamer’s lifelong dissatisfaction steered her toward a fight for voter enfranchisement, and later, as Brooks puts it in her biography, fights “against white supremacy, police brutality, sexual assault, segregated education, food insecurity, and health care access” among others.

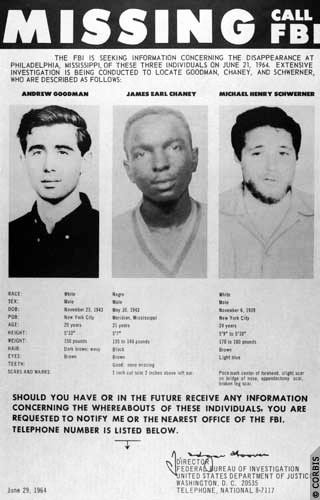

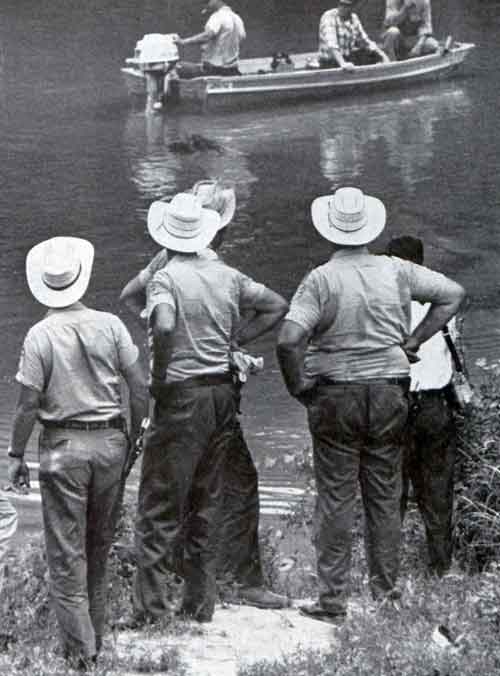

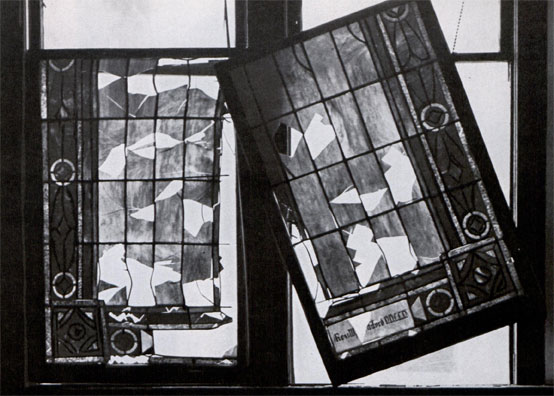

In June, before the convention, three Freedom Summer organizers — James Earl Chaney, Michael Schwerner, and Andrew Goodman — were murdered near Philadelphia, Mississippi. The Ku Klux Klan had grown its numbers in the area and burned down 20 black churches that summer, many of which were hubs for civil rights activity. The three men had been involved with a church that housed a Freedom School, and several Klansmen, policemen, and a minister conspired to shoot them and hide their bodies. The case was a national outrage, but over the course of the federal investigation eight bodies of Black men were found, several of them civil rights workers as well.

After Hamer made the MFDP’s case to the Credentials Committee at the convention, the Johnson administration countered with a negotiation offer: the MFDP could have two at-large seats (picked by Johnson) without unseating any of the Mississippi delegation, and the party would ban segregated delegations in 1968. Hamer and other Freedom delegates were fuming at the prospect of accepting such a paltry deal, but leaders from the NAACP and SCLC, including Martin Luther King, Jr., advised them to take it. The MFDP unanimously voted against accepting the offer, in an outright rejection of the legitimacy of the Mississippi delegation.

That repudiation is an important aspect of Hamer’s legacy in that it refuses to conform to what author Jeanne Theoharis calls the “national fable” of the civil rights movement: the idea that this era of our history can be represented as a settled legislative triumph featuring a small cast of iconic heroes instead of as a disruptive, radical mass movement against institutional white supremacy. Hamer was not interested in a reassuring narrative for white folks; she wanted liberation.

The next month, Harry Belafonte took a group from the MFDP — including John Lewis and Fannie Lou Hamer — on a trip to Guinea. They were received with a warm welcome, meeting President Ahmed Sékou Touré and touring his palace. On the trip, Hamer wrote in her autobiography, she felt she was treated much better in Africa than in America, and she noticed many of the negative stereotypes she had been led to believe about Africans were incorrect. “So when they say, ‘Go back to Africa,’” she wrote, “I say, ‘When you send the Polish back to Poland, the Italians back to Italy, the Irish back to Ireland and you get on that Mayflower from whence you came and give the Indians their land back.’ It’s our right to stay here and we stay and fight for what belongs to us.”

Featured Image Courtesy of the Archives and Records Services Division, Mississippi Department of Archives and History

The Voting Rights Act: Passed, but Present

The Department of Justice called it “the single most effective piece of civil rights legislation ever passed by Congress.” It’s played a role in 22 Supreme Court cases. It’s been subject to five major amendments since it originally passed. And yet, there are still those that would try to undermine it. It is the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and it has proven absolutely essential to the advancement of the country.

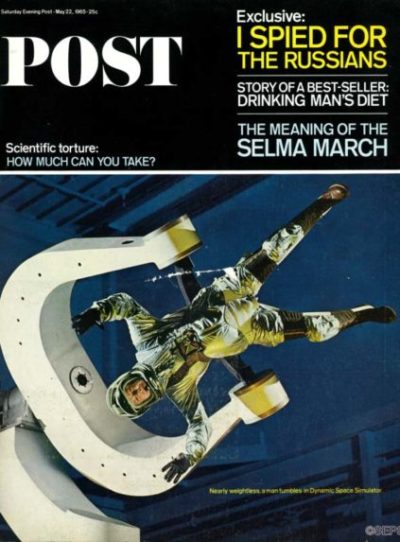

Writ large, the Voting Rights Act is there to prevent racial discrimination against voters. It was signed into law by Lyndon B. Johnson 55 years ago this week after a particularly contentious and violent few months in America. March of 1965 saw the marches from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, three events that The Saturday Evening Post covered at the time. The recently deceased Congressman John Lewis led the first march, an occasion that would be become known as “Bloody Sunday,” after many marchers were attacked by police. President Johnson had called for voting rights action in February, but the focus that the marches put on the issue enabled Johnson to push for such legislation during a televised address to Congress on March 15.

Voting rights had been enumerated in the U.S. Constitution and solidified for all citizens by the so-called Reconstruction Amendments (the 13th, 14th, and 15th). These three amendments also carry language that allows Congress to pass further legislation in the future, should the need arise to provide additional enforcement. The appropriately named Enforcement Acts followed in 1870, making it a criminal offense to interfere with voting rights while also establishing federal oversight for voter registration and elections. However, two Supreme Court decisions in 1875 defanged the Enforcement Acts, meaning that while these new rules were on the books, they were not uniformly interpreted or enforced throughout the country.

After the advent of the modern civil rights movement in the 1950s, Congress would pass three sets of legislation aimed at leveling the playing field in America. Civil rights acts passed in 1957, 1960, and 1964. The broad aim of the 1964 Act was to prohibit discrimination on the basis of color, race, sex, or national origin by state and federal governments, as well as most public places . However, there weren’t enough specifics on voting protections. After the election of 1964, Johnson directed Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach to write a functionally bulletproof act on voting rights; Katzenbach would get input from both Senator Mike Mansfield, the Democratic majority leader, and Senator Everett Dirksen, the Republican minority leader. Mansfield and Dirksen jointly sponsored the Act, and introduced it on March 17, 1965. For his part, Dirksen had been moved to co-sponsor the bill after seeing the violence unfold on Bloody Sunday.

When the bill was formally introduced, a total of 64 more Senators joined as co-sponsors. The House and Senate voted on the Act on August 3 and 4, respectively. It passed the House 328-74, and did the same in the Senate 79-18. Two days later, Johnson signed it into law.

The Act covers two sets of provisions; one set is general, which covers the entire country, and the others are “special,” designated for particular states and local government structures. The Act specifically prohibits discrimination based on race, color, or the spoken language of the voter. Literacy tests, once used in many states to disqualify voters, were banned under Section 2. Section 5 targeted areas that were notorious for a history of illegally disenfranchising voters by specifically noting that they couldn’t make changes to law that countermanded any part of the Act without federal consent.

Of course, very few laws or acts are perfect on the first go-round, so amendments have been applied in subsequent acts. The 1970 and 1975 Acts bolstered discrimination protections for voters with language issues. The biggest 1982 change made it easier to determine if discrimination had happened not just in person, but by the wording used in state laws. The Voting Rights Language Assistance Act of 1992 extended protections that were to expire and expanded support for bilingual voters, including Native Americans. The 2006 Act, properly called the Fannie Lou Hamer, Rosa Parks, and Coretta Scott King Voting Rights Act Reauthorization and Amendments Act of 2006, extended the special provisions for another 25 years.

If there’s a battleground for the Act in the future, it’s likely on the field of gerrymandering; in fact, the Act has already figured into Supreme Court decisions on the topic. Sections 2 and 5 forbid the creation of voting districts that are made in such a way as to intentionally split up the votes of minorities protected by the Act. However, the Supreme Court has held that you also can’t draw districts to favor particular racial composition. It’s a balancing act that will likely result in more challenges going forward.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 represented an important step in the United States. Whether or not it was perfect is beside the point. It was attempt to, for lack of a better phrase, get it right. The great contradiction of America is that it rose under the specter of slavery and has to contend with a Constitution that once called Black people 3/5 of a person. The Act itself represented a long overdue shift, a change that attempted to acknowledge and redress systemic problems in the country. While it’s certain that we have many miles to go, the Act remains a crucial lever in the machine of positive change.

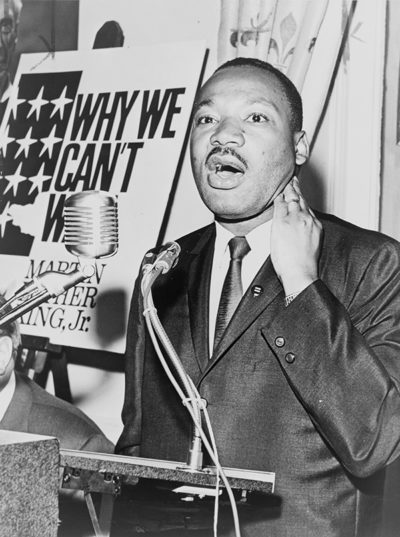

Featured image: President Johnson gave Martin Luther King, Jr. one of the pens used to sign the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (Photo by Yoichi Okamoto; Lyndon Baines Johnson Library and Museum. Image Serial Number: A1030-17a. Public Domain.)

The Unknown Architect of the Civil Rights Movement

When an individual is protesting society’s refusal to acknowledge his dignity as a human being, his very act of protest confers dignity on him.

-Bayard Rustin

In 2013, while awarding a posthumous Presidential Medal of Freedom to civil rights activist Bayard Rustin, President Obama told a story about the organizer on the day of the 1963 March on Washington:

Early in the morning the day of the March on Washington, the National Mall was far from full, and some in the press were beginning to wonder if the event would be a failure. The march’s chief organizer, Bayard Rustin, didn’t panic. As the story goes, he looked down at a piece of paper, looked back up, and reassured reporters that everything was right on schedule. The only thing those reporters didn’t know was that the papers he was holding were blank.

Obama praised Rustin’s “unshakeable optimism” and “nerves of steel,” crediting him for living a life spent on a march toward equality. But he also recognized that the organizer’s story has been relegated to obscurity because he was openly gay.

Just last month, California governor Gavin Newsom pardoned Bayard Rustin, overturning a 1953 conviction in which he was targeted for “lude vagrancy” and marked a sex offender.

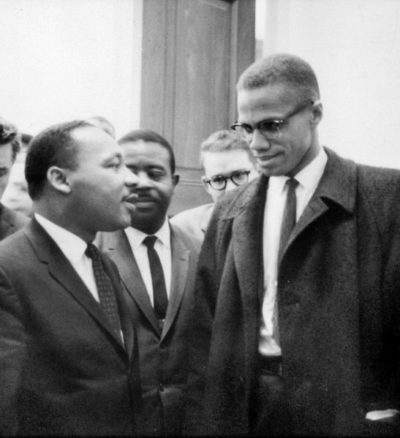

The renewed attention to Rustin’s legacy and unfair treatment comes decades after his death, but it proves the progress that he fought for is closer than ever. As a Quaker, communist, African American, homosexual, pacifist, and leading architect of the civil rights movement, Rustin’s identity and convictions afforded him the perspective to see clearly the country’s societal ills. Unlike Martin Luther King, Jr. or Malcolm X, his contributions to sweeping social justice reform were largely forgotten. Without him, it might not have been possible.

Rustin’s path to activism wound through stints with various radical groups and people. He joined the Young Communist League in 1936, but then severed ties after the Communist Party turned its attention to World War II upon Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union. Rustin refused to serve in the U.S. military during the war and spent two and a half years in federal prison.

Rustin saw around him people objecting to war and injustice in strokes either too violent and radical or too passive and liberal. He found the perfect mentors in pacifist activists A.J. Muste and Asa Philip Randolph, and he went to work for the Fellowship of Reconciliation. As leaders in the labor movement, Muste and Randolph instilled in Rustin both the importance of nonviolent protest and the power of mass action. He believed these could be used to challenge discriminatory laws and economic inequality that oppressed African Americans.

After organizing the first Freedom Rides on interstate buses in the South in the 1940s (and spending 22 days on a chain gang for his civil disobedience), Rustin traveled to India to meet Mohandas Gandhi. Unfortunately, by the time he made it there, Gandhi had been assassinated. Still, the Mahatma’s teachings on combatting injustice stuck with Rustin as he continued his efforts in the U.S.

Rustin began advising a young Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. on nonviolent campaigns during the successful Montgomery bus boycott in the ’50s. He had learned about the effectiveness of strikes and boycotts from the labor movement. “Our power is in our ability to make things unworkable,” he said in a speech in 1956. “The only weapon we have is our bodies, and we need to tuck them in places so wheels don’t turn.”

In 1963, the two worked together again to organize the historic March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. A. Philip Randolph had first conceived of a mass protest in Washington, D.C. for African Americans in 1941, but his event was canceled. With Rustin at the helm, they would attempt to bring thousands of people to the city in the largest demonstration for civil rights in the country’s history.

As the date of the march approached, South Carolina senator Strom Thurmond attacked Rustin’s history of “sexual perversion,” draft dodging, and his affiliation with the Communist Party, but King defended Rustin’s invaluable place in the movement. His experience with organizing groups of people for various causes would prove instrumental in the success of the March on Washington.

Video footage from the march shows Bob Dylan and Joan Baez singing “When the Ship Comes In” as Rustin walks behind them, dragging from a cigarette. When he took the stage, Rustin began, “Ladies and gentlemen, the first demand is that we have effective civil rights legislation; no compromise, no filibuster, and that it include public accommodations, decent housing, integrated education, FAPC, and the right to vote. What do you say?” The crowd answered with a thunderous roar. The iconic event gathered more than 200,000 people in the National Mall and permanently altered the struggle for racial justice.

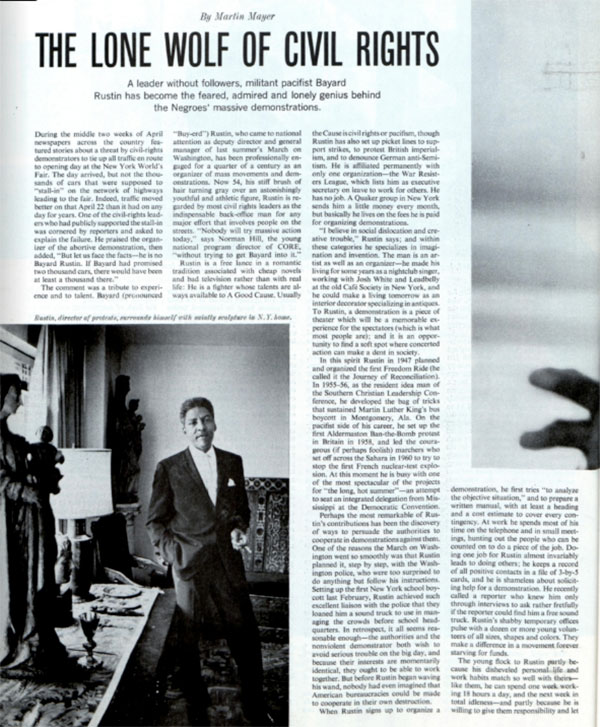

The spring after the March on Washington, this magazine published a profile of Rustin (“The Lone Wolf of Civil Rights”), calling attention to his long career in troublemaking. Rustin was decidedly nonviolent, but his approach to public protest was strictly tied to results: “Rustin insists that every demonstration he runs will be related immediately to a specific objective. Freedom rides and lunch-counter sit-ins are ideal, because they call attention directly to the evil being fought and at the same time establish a strong bargaining position for the negotiations which must be the result of any successful demonstration.”

In the Post’s report, author Martin Mayer notes Rustin’s apparent outsider status in many organizations fighting for civil rights in the ’60s. Mayer claims Rustin’s independence at the time was an organizing strategy or, perhaps, a consequence of his difficult personality, only once mentioning his “morals charge” in California. In hindsight, Rustin’s living openly as a gay man for most of his life (as anyone who met him would attest to) cost him dearly in his relationships and his ability to lead organizations. He broke off with the Fellowship of Reconciliation after several years of defending his sexual orientation to Reverend A.J. Muste, and he faced a short stint of dissociation from Dr. King for fear of sullying the leader’s reputation.

After King was assassinated, Rustin found himself at odds with the more radical Black Power movement (particularly the gun-wielding Black Panthers) as he stayed the course of marrying the civil rights movement to trade unions. Rustin became interested in moving from “protest to politics,” as far as civil rights were concerned, but he took on new issues around the world, like the plights of Soviet Jews and Thai refugees. In a 1986 speech called “From Montgomery to Stonewall,” Rustin drew comparisons between the new gay rights movement and the civil rights movement he had orchestrated:

Our job is not to get those people who dislike us to love us. Nor was our aim in the civil rights movement to get prejudiced white people to love us. Our aim was to try to create the kind of America, legislatively, morally, and psychologically, such that even though some whites continued to hate us, they could not openly manifest that hate. That’s our job today: to control the extent to which people can publicly manifest antigay sentiment.

Rustin died the year after giving that speech to a gay student group at University of Pennsylvania. In it, he assured the students that they must continue fighting for their cause no matter how difficult it was. He said that fighting for legislation was crucial, but noted that often liberation emerged from the culture influenced by the movement itself. “We never got an antilynch law,” he said, “and now we don’t need one.”

Featured image by Bert Shavitz

Considering History: “There’s Time Enough, but None to Spare” — A Black History Month Lesson in Critical Optimism

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

If you’re like me, much of the news has felt pretty close to apocalyptic for some time now, but the first month of 2020 has taken things to another level. The assassination and reprisal that pushed the U.S., Iran, and perhaps the world to the brink of war. The raging Australian wildfires that killed billions of animals, sent smoke as far away as New Zealand, and (along with the seemingly constant Puerto Rican earthquakes) foreshadowed a year of accelerating climate catastrophes. The deadly mega-virus that is sweeping China and Southeast Asia and has led the World Health Organization to declare a global emergency for only the sixth time in its history. The impeachment debates in which a prominent Republican Senator admitted in an extended Twitter thread that the president illicitly sought foreign interference in the 2020 election and illegally covered it up — and then that Senator voted not to have witnesses at the trial.

In light of all these and so many other stories, it can feel difficult, if not downright impossible, to maintain hope for the future. But there’s a corollary concept to the critical patriotism I discussed in my Martin Luther King Day column: critical optimism. This form of optimism, which I defined and advocated as part of my book History and Hope in American Literature: Models of Critical Patriotism (2016), recognizes and engages with the hardest and worst of our world, yet seeks to find reasons for hope nevertheless, not despite those realities but through and beyond them. And as we begin Black History Month, it happens that one of the most critically optimistic texts I know was authored by an African-American author and focuses on an act of racial terrorism: Charles W. Chesnutt’s The Marrow of Tradition (1901), a historical novel inspired by the horrific 1898 Wilmington (North Carolina) white supremacist coup and massacre.

Chesnutt’s life and career themselves modeled critical optimism in response to some of America’s bleakest realities. The grandson of enslaved people and son of two free African Americans who moved their family from North Carolina to Ohio just before the Civil War, Chesnutt chose to return to North Carolina after the war and work as an educator and principal during Reconstruction. Both of his grandfathers were likely white slave owners and he was light-skinned enough to be mistaken for white many times in the course of his life, but Chesnutt consistently and publicly defined himself as African American and dedicated his writing career to (as he wrote in his journals) “exalt my race.” And when editors and publishers sought to pigeon-hole his writing into the late 19th century’s “plantation tradition” genre, he both exploded that genre’s conventions (in his book of “conjure tales”) and wrote socially realistic and politically activist novels that defied such categorizations altogether.

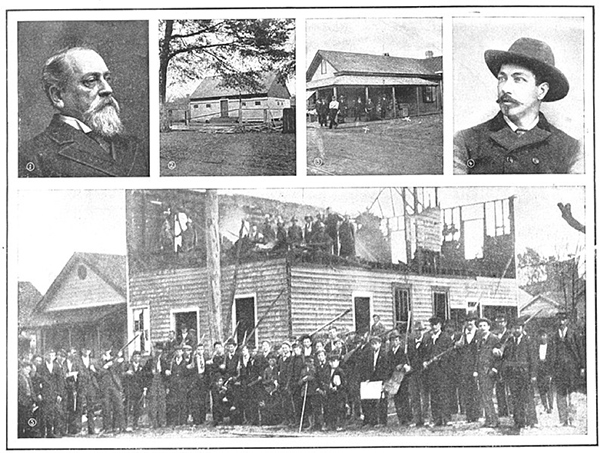

The best of those novels, and one of American culture’s most vital representations of both horrific histories and critical optimism, is The Marrow of Tradition. Chesnutt’s North Carolina roots and life were in Fayetteville, about 90 miles northwest of Wilmington, but he had many relatives and friends in the Wilmington area and knew the city well. As of 1898, Wilmington was one of the few cities in the state (and indeed throughout the South) in which the region’s resurgent white supremacists had not taken power; the city’s mayor and most other elected officials were at the time part of the Fusion Party, a progressive North Carolina political movement that brought together African Americans and radical white allies. White supremacists were frustrated by that state of affairs and angered by a newspaper editorial in which Alexander Manly, the African-American owner and editor of the Wilmington Daily Record (perhaps the only black-owned daily paper in the nation), highlighted the horrific truths of the lynching epidemic. As a result, the white supremecists spent months planning a domestic terrorist attack on the city.

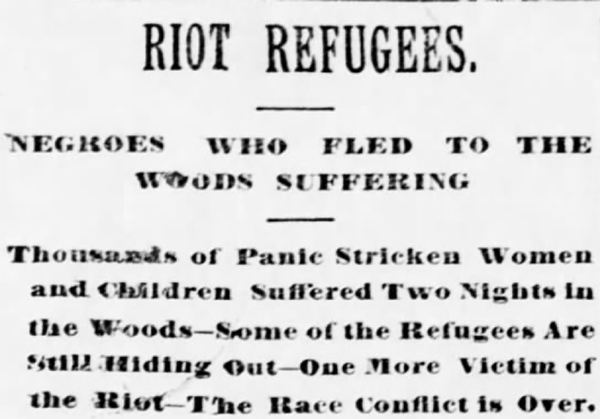

That attack unfolded on election day, November 10th, 1898. It included the only coup d’etat in American history, as the city’s elected officials were violently forced out and replaced by hand-picked white supremacist leaders. It also featured the massacre, an orgy of violence targeting the city’s African-American community. White supremacist militias traveled from around the state to take part in the attacks, bringing with them, among many other weapons, a Gatling gun that rolled through town on a cart firing indiscriminately. By the time the day was done they had burned down the Daily Record and many other buildings, killed hundreds of African-American residents and injured many more, and essentially destroyed the city’s black community for generations. The newly installed white supremacist “Revolutionary Mayor,” Alfred Waddell, would two weeks later write a story for Collier’s Magazine, designating the event a “race riot” and blaming its violence on a mythical African-American mobs and its supporters.

Both those horrific histories and that media misrepresentation inspired Charles Chesnutt to write a novel about the massacre. Set in the fictionalized city of Wellington, Chesnutt’s sweeping historical novel depicts many elements of the late 19th century South and nation, including the aftermath of slavery and the Civil War, the rise of both the KKK and Jim Crow segregation, the lynching epidemic, and life for mixed-race individuals in a society organized so thoroughly around the color line. But the novel builds to a multi-chapter depiction of the massacre and coup, a bracing portrayal that delves into the heart of that day’s violence and ends with one of the bleakest and most biting sentences in American literature. The white supremacist mob has burned down the city’s African American hospital, and Chesnutt’s narrator observes, “The flames soon completed their work, and this handsome structure, … a promise of good things for the future of the city, lay smoldering in ruins, a melancholy witness to the fact that our boasted civilization is but a thin veneer, which cracks and scales off at the first impact of primal passions.”

No line could better sum up the worst of American history, exemplified by Wilmington but present in so many moments. Yet Chesnutt does not end his novel there, and instead creates a pair of final chapters that offers an example of critical optimism in the face of these horrors. Without spoiling all of their details (this is a novel that all Americans should read, now more than ever), I will note that Chesnutt puts two of his central African-American protagonists in a position to exact a small but significant moment of justice and retribution for the day’s and their society’s brutalities, one that they have deeply personal reason to desire. Yet that deserved justice would target a white infant, innocent of all these horrors and a potent symbol of the uncertain future facing the city and the nation. And the two characters choose instead to be closer to the ideals — national, spiritual, human — that their white counterparts have so thoroughly forgotten.

As the novel closes, it seems likely but not inevitable that this moment of critical optimism will succeed, that the infant will live, that a better future than this horrific present remains possible. The novel’s final line is, “There’s time enough, but none to spare.” Here in February 2020, I can’t imagine a more important pair of lessons than those provided by Charles Chesnutt and The Marrow of Tradition: the desperate need to confront the worst of our histories, of what white supremacy has been and done and remains in America; and the equally urgent possibility of seeking a better future, not despite but through and beyond our histories. Now more than ever, we need the critical optimism of this vital American novel.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Considering History: Martin Luther King Jr. and the Legacies of Critical Patriotism

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

Over the half-century since his tragic assassination, Martin Luther King Jr. has gradually become one of those figures whose legacy is claimed on behalf of numerous positions and perspectives. Whatever the goals of those competing contemporary claims, it’s fair to say that any of them risks turning King and the Civil Rights Movement into images and icons rather than a multi-layered historical figures and events. The Martin Luther King Day holiday offers an important moment to step back from those trends and remember the histories themselves and the lessons they provide.

One of the most important such historical lessons is the central role of civil disobedience in King’s actions throughout the Civil Rights Movement. King’s emphasis on civil disobedience was inspired in part by his engagement with earlier models of that form of activism, including Henry David Thoreau’s war tax resistance and his essay “Resistance to Civil Government” (1849) and Mahatma Gandhi’s leadership of the movement for Indian independence.

But his emphasis on civil disobedience also locates King within the long tradition of African-American critical patriots. Critical patriotism as a concept challenges traditional definitions of patriotism as simply a celebration of the nation and support of the government.

Earlier this month, the tagline for a Washington Post article on the role of the journalist in times of war succinctly illustrated that narrative of traditional patriotism: “Are you a journalist first or an American first? With conflict looming, an old question about patriotism is raised anew.” In this vision, to be a patriotic American is to support the nation and express that support by participating in shared communal celebrations such as the national anthem and the Pledge of Allegiance.

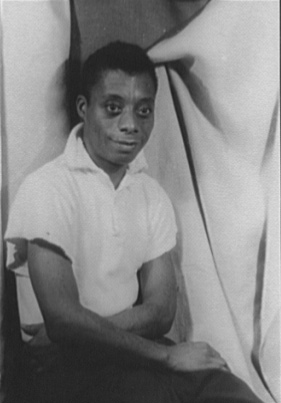

That celebratory form of patriotism is often associated with phrases like “Love it or leave it,” with the idea that if one does not share such a perspective, one is both unpatriotic and undeserving of being part of the national community. But in a striking quote from his essay collection Notes of a Native Son (1955), James Baldwin, King’s contemporary and one of the era’s most eloquent and vital literary and cultural voices, models a contrasting vision of both the love of one’s country and patriotism. “I love America more than any other country in the world,” Baldwin writes, “and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.”

That critical form of patriotism has been exemplified by many figures throughout American history, but African Americans have a particularly rich legacy of critical patriotism. “It is black people who have been the perfecters of this democracy,” argues journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones in the introductory essay for the 1619 Project, the August 2019 New York Times Magazine public scholarly work she initiated and directed. Seen through this lens, for example, histories of slave resistance and revolt comprise not just quests for individual and collective freedom, but efforts both to force the nation to grapple with its failings and to move it closer toward its ideals of “liberty and justice for all.”

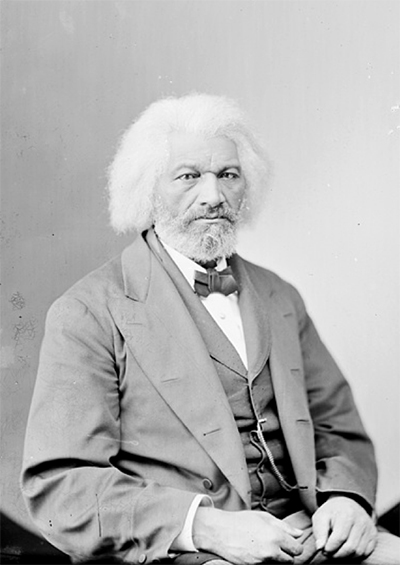

One of the most influential voices of critical patriotism, Frederick Douglass, modeled those efforts in his speech “What to the Slave is the 4th of July?” (1852). Invited to speak at a Rochester, New York celebration of that holiday, Douglass offers instead a potent critique of that occasion:

Fellow-citizens, pardon me, allow me to ask, why am I called upon to speak here today? What have I, or those I represent, to do with your national independence? Are the great principles of political freedom and of natural justice, embodied in that Declaration of Independence, extended to us? … This Fourth of July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn. (Douglass’ emphasis).

Douglass goes further, arguing that it is precisely such critique which is required:

At a time like this, scorching irony, not convincing argument, is needed. O! had I the ability, and could I reach the nation’s ear, I would, today, pour out a fiery stream of biting ridicule, blasting reproach, withering sarcasm, and stern rebuke. For it is not light that is needed, but fire; it is not the gentle shower, but thunder. We need the storm, the whirlwind, and the earthquake. The feeling of the nation must be quickened; the conscience of the nation must be roused; the propriety of the nation must be startled; the hypocrisy of the nation must be exposed; and its crimes against God and man must be proclaimed and denounced.

And he ends by making clear his patriotic purpose:

Allow me to say, in conclusion, notwithstanding the dark picture I have this day presented of the state of the nation, I do not despair of this country…I, therefore, leave off where I began, with hope.

The 1619 Project levies its own critiques of 1776 and our celebration of the Revolution, and as a result has become in recent months the subject of extended critiques in its own right, including attacks that have labeled it “unpatriotic” and “anti-American.” But like Douglass, King, and so many others, the Project expresses the two interconnected layers to critical patriotism:

- highlighting the manifold historical moments in which the nation has failed to live up to those ideals

- remembering and carrying forward the work of the figures and communities that have challenged those shortcomings and sought to move the nation closer toward the “more perfect union” envisioned in the Constitution’s Preamble

Another contemporary figure who has been frequently labeled as unpatriotic is Colin Kaepernick. In an August 2016 ESPN piece published shortly after Kaepernick began his controversial national anthem protests, his fellow NFL quarterback Drew Brees argued, “I disagree. I wholeheartedly disagree…it’s an oxymoron that you’re sitting down, disrespecting that flag that has given you the freedom to speak out.” Brees’s comments concisely illustrate how many Americans equate patriotism with demonstrating “respect for the flag” (and often, in critiques of Kaepernick, “support for the troops”) by participating fully and unequivocally in communal celebrations like standing for the national anthem.

Yet Kaepernick chose to kneel after consulting with former NFL player and Green Beret Nate Boyer over what form of protest would be most respectful to American veterans and servicemen and women. And in his public statements he linked that protest to both layers of a critically patriotic perspective mentioned above: highlighting the nation’s shortcomings (“That’s something that this country stands for: freedom, liberty, justice for all. And it’s not happening for all right now”); and seeking to move the nation closer to its ideals (“To me this is something that has to change and when there’s significant change and I feel like that flag represents what it’s supposed to represent in this country, is representing the way that it’s supposed to, I’ll stand”).

Kaepernick’s protest, like the 1619 Project, are open to response and debate. But labeling such efforts as unpatriotic reveals a limiting vision of patriotism as simply and solely the celebratory form. On Martin Luther King Jr. Day, let’s remember an alternate, critical form of American patriotism, one carried forward by both King and these contemporary voices.

Featured image: Martin Luther King Jr. (Library of Congress)

Considering History: Emmett Till’s Casket and the Worst and Best of America

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

In the early morning hours of August 28, 1955, Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam abducted and lynched Emmett Till near the small town of Money, Mississippi. Till, who had just turned 14 years old a month earlier, lived in Chicago with his single mother Mamie; Mamie’s parents had left Mississippi as part of the Great Migration when she was just two years old, and in the summer of 1955 Emmett returned to the area for the first time, staying with Mamie’s uncle Mose Wright and his family. On the morning of August 24 Emmett and his cousin Curtis visited Bryant’s Grocery and Meat Market, where 21-year-old Carolyn Bryant was working by herself; according to Bryant’s testimony at the time, Emmett accosted her both verbally and physically. When her husband Roy returned from a fishing trip on August 27, Carolyn told him her version of the encounter, and he and his half-brother J.W. set out on a mission of revenge and racial terrorism that ended with the brutalizing and murder of Emmett.

Virtually every detail of Till and Bryant’s initial encounter remains in dispute, not least because Carolyn Bryant herself has in recent decades recanted some crucial aspects of her testimony (such as the physical side to the altercation). Roy and J.W.’s lynching of Emmett was never in dispute, yet the two men were acquitted on all charges by an all-white jury in a high-profile September 1955 trial. All those histories tell us a great deal about Mississippi, the South, and America, in 1955 and in our own moment. Yet there is another vital side to our collective memories of Emmett Till, one captured by his moving memorial at the National Museum of African American History & Culture.

The centerpiece of the NMAAHC’s Till memorial is his casket — not a replica, but the actual casket in which Till was buried after his early September funeral in Chicago. The Department of Justice exhumed Till’s remains as part of a 2005 investigation into his kidnapping and murder, and he was re-buried in a new casket; the old casket was stored at the cemetery and discovered in 2009. The NMAAHC, still in development at the time, acquired the casket soon after; as Director Lonnie Bunch III put it, “It is an object that allows us to tell the story, to feel the pain and understand loss. I want people to feel like I did. I want people to feel the complexity of emotions.”

When I visited the NMAAHC with my sons and my parents a couple weeks ago, it was indeed the Till memorial that most affected us all (which is no slight on the whole of this must-visit museum). We did feel that pain and understand that loss, as it’s impossible not to contrast the exhibit’s photos of young Emmett (as a baby, as a young boy alongside his mother, and as a smiling teenager just months before his murder) with the photos and stories of his lynching and, most potently, with that adolescent-sized casket, past which visitors to the memorial walk as if at a funeral service.

As that casket reminds us, the pain and loss of Emmett’s lynching was felt with particular force by Mamie. She had already lived through more than her share of struggle, including her family’s migration, her parents’ divorce when she was 13, and, especially, her abusive marriage with Emmett’s father Louis Till. They were only 18 when they married in 1940, and he was consistently abusive, culminating in his choking Mamie to unconsciousness in 1942 (when Emmett was about 1). After that assault she took out a restraining order on Louis, and when he violated it repeatedly he chose enlistment in the army rather than prison. In July 1945 Louis was court-martialed and executed in Italy for murder and rape, leaving Mamie and Emmett as a pair of survivors, a tight family unit on Chicago’s South Side.

For a parent to lose their child in any way is a tragedy; for Mamie to lose her only child in this sudden and brutal manner is a trauma too horrific to imagine. Yet as the museum’s open casket likewise reminds us, Mamie responded to that trauma with a pair of stunning and crucial choices: making Emmett’s funeral service public and, most potently, insisting on an open-casket service. “I wanted the world to see what they did to my baby,” she argued, and tens of thousands of mourners did see Emmett’s brutalized young body (with photographs being seen by millions more). Mamie then embarked on an NAACP-organized speaking tour, sharing her loss and trauma and son and voice with audiences around the country.

As the NMAAHC’s exhibit highlights in depth, Mamie’s choices became hugely inspirational for the nascent Civil Rights Movement and some of its most significant figures and actions. As Myrlie Evers put it, “Somehow [it] struck a spark of indignation that ignited protests around the world. … It was the murder of this 14-year-old out-of-state visitor that touched off a world-wide clamor and cast the glare of a world spotlight on Mississippi’s racism.” Or, as Rosa Parks put it more succinctly, when describing to Mamie Till herself the moment when Parks refused to move to the back of that Montgomery bus, “I thought of Emmett Till and I just couldn’t go back.”

The recent launch of the New York Times’s 1619 Project has prompted renewed debate about whether and how to remember our nation’s most violent and oppressive histories. Critics of the project (those not blatantly advancing white supremacist talking points) argue that dwelling on these painful histories is divisive and destructive to our present and future. Yet until we can feel the pain and understand the loss, how we can possibly grapple with not only the histories themselves, but the nation that has featured them so consistently and centrally? We can only do so by standing before the casket — and when we do, we can also remember the ways in which figures like Mamie Till, Rosa Parks, and so many more have experienced and yet transcended our worst, modeling the best of what we might still become.

Featured image: Emmett Till with his mother, Mamie Bradley, ca. 1950 (Alamy)

5 Ways Your Vote Might Not Count

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 was meant to break down obstacles to voter registration that had kept minority groups out of the polls for most of American history. Besides outlawing literacy tests, the act allowed the U.S. attorney general to investigate poll taxes, which had been banned for federal elections in 1964, and state elections in 1966. Section 5 of the act required federal oversight of 11 states where at least 50 percent of the non-white population was not registered to vote.

The Voting Rights Act was seen as a major victory of the civil rights movement and was considered a breakthrough in making sure every citizen had access to one of their most basic rights.

Half a century later, having a voice in American government is not as simple as showing up to the polls on election day. Here are five reasons your political voice may go unheard.

1. Use-it-or-lose-it Registration Laws

It’s impossible for your vote to count if you never get to cast it. Some states have instituted strict registration laws that make it harder for potential voters to stay registered. One example is Ohio’s “use-it-or-lose-it” law that allows the state to unregister voters who have not cast a ballot in a set amount of time. If you go two years without voting the state sends you a warning in the form of a post card. If you go a further four years (missing one presidential election) without responding or voting, the state removes you from voter rolls.

This law was upheld by the Supreme Court case Husted v. A. Philip Randolph Institute in 2017. It has contributed to the removal of two million voters between 2011 and 2016. And, as Justice Sonia Sotomayor noted in her dissenting opinion, “has disproportionately affected minority, low-income, disabled, and veteran voters.”

2. Exact Match System

The exact match system also presents an obstacle in voter registration. This Georgia law requires the name on your ID to exactly match the name on your registration form. Using “Jim” on the form and having “James” on your ID, for example, would result in disqualification. Even one hyphen or letter out of place will prevent you from voting.

Critics of this system also argue that the exact match system unfairly affects communities of color, as their names would be less familiar to workers entering names into voter registration systems. As such the exact match system has come to be known as “disenfranchisement by typo.”

3. Mailing Address Required

North Dakota requires a current street address as voter identification. This policy prevents voters without a residential street address from registering to vote.

More specifically, most Native Americans living on reservations, (more than 18,000 in North Dakota), use P.O. boxes instead of residential addresses. The policy dictates that the address must be a street address and does not accept P.O. boxes, keeping those living on reservations from the polls. The Supreme Court upheld this law in 2018.

4. Felons Can’t Vote

All but two states (Maine and Vermont) revoke your right to vote upon conviction of a felony. In 14 states and Washington, D.C., this right is automatically restored upon release. In 22 states the right to vote is restored after a waiting period, completion of parole, or independent action of voters. The remaining 12 states require further action to restore the right (such as longer waiting periods or a governor’s pardon) and for some crimes the right to vote is never restored.

In 2018 Florida passed a law that would restore the right to vote to former felons who have already paid their debt the society. This law gave voting rights to 1.4 million people, the largest mass enfranchisement since the Voting Rights Act. This brief moment of victory was quickly followed with a law passed in May of 2019 that required all former felons to pay off back fines and fees to the court before they can vote again. Similar laws exist in four other states, and three states require former felons to personally apply to state legislatures for their voting right to be restored (Arizona requires this only for second-time offenders).

5. Finding a Polling Place

The Voting Right Act’s Section 4 was ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 2013. The Shelby County v. Holder decision stated that times have changed and states with a long history of voter suppression no longer needed voting policies monitored by the Attorney General or a Washington, D.C. district court. A 2016 study by the Leadership Conference Education Fund found that “Out of the 381 counties [formerly under federal supervision], 165 of them — 43 percent — have reduced voting locations.” At the time of the study, 868 polling locations had closed across the previously monitored states. The closures have continued since 2016.

In Georgia, specifically, over 200 polling places have closed in recent years. The Leadership Conference study claims that the lack of polling places and early voting locations “place[s] an undue burden on minority voters, who may be less likely to have access to public transportation or vehicles, given continuing disparities in socioeconomic resources.”

Voting is much more complicated than simply showing up. The Voting Rights Act aimed to include more Americans in the political discussion. but there is still more that needs to be done. As Lyndon B. Johnson said when introducing the Voting Rights Act “There is no moral issue. It is wrong–deadly wrong–to deny any of your fellow Americans the right to vote in this country.”

Featured image: Shutterstock

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 Still Works for You

Rights can be precarious things. In the political present, states pass laws that conflict with Supreme Court decisions, and issues of individual rights come into question at traffic stops and borders. Remarkably, rights were even less certain in the 1960s. That’s one reason that we stop to remember that President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Acts into law 55 years ago today. Despite this being a monumental piece of legislation, people are often confused about what it means and what protections it affords. The Act impacts everything from voting to schools to where court cases are heard and beyond. Let’s take a look at some of the most important pieces of the act, as well as the updates made in 1968 and 1991.

President Kennedy’s 1963 Civil Right Address (Uploaded to YouTube by JFK Library)

President John Kennedy had proposed the act in 1963, and Representative Emanuel Celler of New York introduced it, but a filibuster in the Senate ground its passage to a halt. After Kennedy was assassinated, Johnson made it a priority to drive the bill forward, and signed it upon its passage on July 2, 1964. The broad idea of the 1964 Act is fairly simple to grasp: It aims to prohibit discrimination on the basis of color, race, sex, or national origin by state and federal governments, as well as most public places. This larger concept is tackled in 11 titles under the act. In simple terms,

- Title I requires that voting rules and procedures be applied equally to all eligible voters.

- Title II forbids discrimination in “public accommodations” like movie theaters, hotels, and restaurants (though it didn’t go so far as to include private clubs).

- Title III enshrines access for all to public facilities.

- Title IV desegregated public schools and also empowers the Attorney General to file suits to enforce desegregation.

- Title V expanded the S. Commission on Civil Rights, which had been created by the earlier Civil Rights Act of 1957.

- Title VI bans any discrimination by programs that receive federal funds.

- Title VII was constructed to create equal opportunity practices for employment.

- Title VIII was geared toward statistics, making it mandatory to track both voter registration and voting data in places decided upon by the Commission on Civil Rights.

- Title IX (not to be confused with the more-famous Title IX of the Education Amendments Act, which pertains to college sports and beyond) eases the movement of civil rights cases from state courts to federal courts, a rule that was applied because discrimination-based proceedings had a difficult time getting heard in certain states.

- Title X authorized the creation of the Community Relations Service, which is part of the Department of Justice; the service works to mollify community tension and conflicts brought out by acts related to discord between groups in which race, etc. may have played a part.

- Title XI affords protection for defendants of criminal contempt in certain permutations of cases arising from any of the other articles.

No piece of legislation is perfect, but overlooked or unexpected divergences from earlier laws can be corrected or updated in later bills. The Civil Rights Act of 1968 made efforts to address civil rights for Native Americans, as well as tackling housing discrimination in the Fair Housing Act (which is composed of Titles VIII and IX in the text). Labor was addressed in the Civil Rights Act of 1991, guaranteeing the right to a jury trial in cases of discrimination claims while also strengthening the ability of women to sue for sexual harassment or discrimination at work.

Today, inequalities still exist, but the 1964 Civil Rights Act remains one of the most comprehensive attempts to address them. Its passage made possible subsequent legislation, like the Americans with Disabilities Act and the more recent protections afforded to LGBTQ citizens. Our current cultural moment finds us still dealing with fractured communities and the pains of the past. By recognizing these inequities and attempting in some small way to mitigate them, steps like the Civil Rights Act keep us on the path that Kennedy envisioned when he said, “We cannot say to 10 percent of the population that you can’t have that right; that your children cannot have the chance to develop whatever talents they have; that the only way that they are going to get their rights is to go in the street and demonstrate. I think we owe them and we owe ourselves a better country than that.”

Featured image: President Lyndon B. Johnson signs the Civil Rights Act of 1964 as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and others observe. (Photo by Cecil Stoughton of the White House Press Office; Wikimedia Commons)

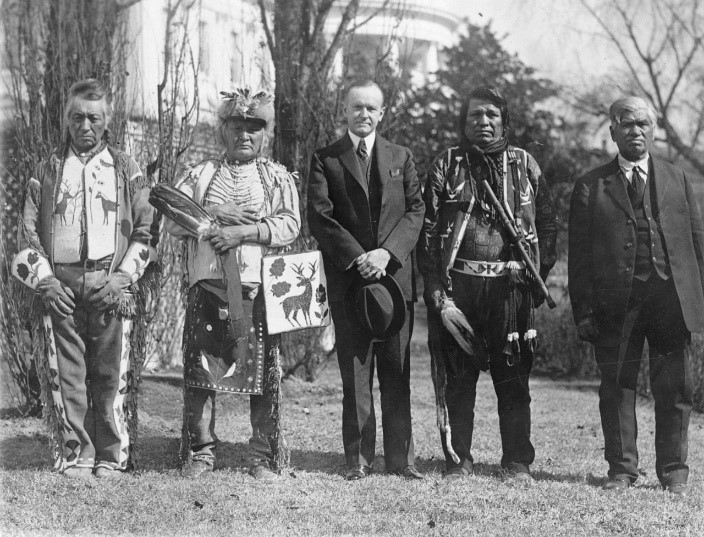

Considering History: The Fight for Native American Citizenship and Voting Rights

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

Native American issues and identities have taken center stage in our political conversations over the last two weeks. On October 9, the Supreme Court issued a last-minute ruling upholding North Dakota’s controversial voter ID act, a law that by requiring voters to have a residential address effectively disenfranchises Native Americans living on the state’s many reservations. And on October 15, Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren responded to Donald Trump’s longstanding attacks on her claims to Native American ancestry by releasing the results of a DNA test featuring “strong evidence” of native heritage.

The Warren story has dominated much of these recent political and media conversations. While that story does offer a potential opening for important discussions of how we define Native American identity and community, it also serves as an unfortunate distraction from the unfolding battle over the North Dakota law and what it means for 21st century Native American rights and communities. And this contemporary battle becomes even more meaningful when placed in the context of the complex and contested history of Native American citizenship and voting rights.

These debates over native sovereignty are longstanding and ongoing. To many scholars and activists, Native American tribes exist outside of (and equal to) the United States. Viewed through that lens, Native Americans should, one day, be able to seek dual citizenship from both their tribe as well as from the United States; their voting rights would, therefore, be tied to that legal and political status.

Despite this status, native citizenship has been tenuous and hard-won. The 14th Amendment to the Constitution, passed by Congress in June 1866, was a watershed moment in the expansion of American citizenship — but not for Native Americans. While it extended protections to all former slaves and their descendants and enshrined into law the concept of “birthright citizenship” for all those born in the United States, this amendment did not apply to all Americans. As a number of subsequent court cases reiterated, the law defined Native Americans as “wards” of the state instead, leaving them outside of this otherwise all-encompassing revision of the national community.

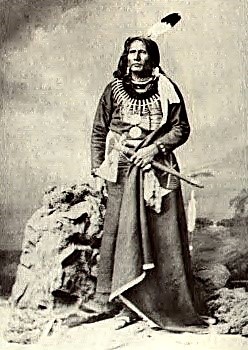

Late 19th century native activists and their allies, however, did not allow this discriminatory exception to go unchallenged. In 1879, Ponca Chief Standing Bear, who had undertaken an extensive protest and speaking tour in order to raise awareness of his tribe’s unlawful and violent treatment at the hands of the U.S. government and military, sued General George Crook. Standing Bear’s suit challenged both the Ponca tribe’s displacement from their Nebraska homeland to an Oklahoma reservation and his personal imprisonment by General Crook (for illegally leaving that reservation in order to stage his protests). After a lengthy and highly public trial, Judge Elmer Dundy ruled in Standing Bear’s favor, noting in his decision that “an Indian is a person” and that “[Indians] have the inalienable right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

The actions of Chief Standing Bear, along with other victories such as the new (if still circumscribed) opportunities for native citizenship granted by the 1887 Dawes Act, helped push the nation toward a slow, but full recognition of Native American citizenship. This recognition came, mostly, in the form of the 1924 Indian Citizenship Act, which declared “all non-citizen Indians born within the territorial limits of the United States…to be citizens of the United States,” so long as “the granting of such citizenship shall not in any manner impair or otherwise affect the right of any Indian to tribal or other property.”

Yet as many other groups of Americans throughout our history have long known, full citizenship does not necessarily entail equal voting rights (despite the 15th Amendment’s guarantee that it does). Indeed, through at least the late 1950s, many states maintained laws that prohibited Native Americans from voting. In New Mexico, for example, the state constitution explicitly barred Native Americans living on reservations (the vast majority of the state’s native population) from voting in either state or federal elections. That constitutional discrimination was challenged by native and civil rights activists as early as 1948, but wasn’t amended until 1962.

Even with such changes to state law, coupled with the nationwide protections afforded by the 1965 Voting Rights Act, the battle to ensure and protect Native American voting rights has persisted throughout the 20th century and into the present day. The American Indian Movement (AIM) — too often known only for its controversial occupations and legal cases, such its ongoing fight to free Leonard Peltier from prison — has pursued Standing Bear’s legacy, pushing the struggle for voting rights into our present century. The most recent challenges to the Voting Rights Act and voting access have likewise drastically affected native communities, and are the subject of continued challenges from native activists and their allies, such as the efforts by a number of Arizona tribes to contest that state’s new, labyrinthine Voter ID requirements.

In North Dakota, Arizona, and elsewhere, voting rights and voter suppression efforts have become a central story in the final weeks before the crucial 2018 midterm elections, and rightly so. But the more we can engage with the longstanding debates over and battles for citizenship and civic participation, the more we can recognize the true significance and stakes of these 21st century conflicts.

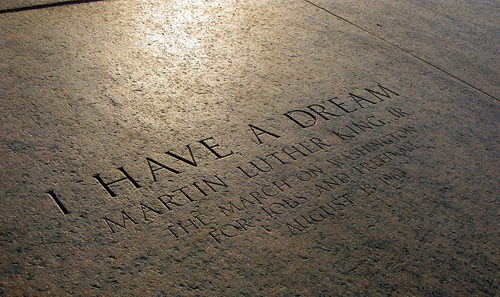

Five Things You Didn’t Know About the “I Have a Dream” Speech

Few words echo through history with the conviction and power of the “I Have a Dream” speech, given by Martin Luther King, Jr. 55 years ago today. Frequently ranked as the top speech in American history by polls and scholars, the address served as the defining moment of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. King and other organizers mounted the march in support of civil rights legislation initiated by President John F. Kennedy. All of that could be considered common knowledge; here are a few things that you might not know about the speech and the events surrounding it.

The Speech.

1. It Wasn’t King’s First “Dream” Speech

When you look back at Dr. King’s oratorical history, it’s obvious that he liked to use dream allusions and imagery. It’s not difficult to understand why, as the civil rights struggle is essentially a dream of equality. King used that theme in a speech he gave to the NAACP in 1960 called “The Negro and The American Dream” in which he called America “a dream yet unfulfilled.” The speech emphasized that contributions that black Americans had already made and could continue to make and decried institutional racism, noting, “The primary reason for uprooting racial discrimination from our society is that it is morally wrong. It is a cancerous disease that prevents us from realizing the sublime principles of our Judeo-Christian tradition. It relegates persons to the status of things.” King would use the “dream” concept in further speeches in North Carolina in 1962 and Detroit in 1963, among other occasions.

2. The Speech Caught the Attention of the FBI

From 1956 to 1971, the FBI ran a series of operations that sought to dismantle domestic political groups. The umbrella name was COINTELPRO, which was derived from Counter Intelligence Program. Although the projects began by targeting the Communist Party in the United States, they expanded widely and involved infiltration, harassment, and, at times, violence directed against groups as diverse as the civil rights movement, feminist organizers, the Black Panther Party, the KKK, Puerto Rican independence activists, and more. King himself was a specific and frequent target of investigations and wiretaps as some people inside the Bureau viewed him as subversive. In Tim Weiner’s 2012 book, Enemies: A History of the FBI, Weiner offers a quote from FBI director J. Edgar Hoover in the wake of the “Dream” speech in which he says, “We must mark [King] now if we have not done so before, as the most dangerous Negro of the future in this nation from the standpoint of communism, the Negro, and national security.” The operation was overtly halted in 1971 after it was exposed by the activist group the Citizens’ Commission to Investigate the FBI.

3. It Made History in 17 Minutes

The speech itself took King 17 minutes to deliver. It has an official count of 1,667 words. That’s just over six times longer than Lincoln’s “Gettysburg Address,” which is widely considered King’s model for “I Have A Dream.”

4. The Speech Had Other Unshakable Lincoln Connections

The opening of the “I Have A Dream” speech includes the words “Five score years ago,” followed by a direct reference to the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation, the document that freed all the enslaved people in the south. Slavery officially ended in the United States with the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865. Of course, the speech was delivered at the incredibly appropriate location of the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. Today, a marble marker on the steps memorializes the occasion.

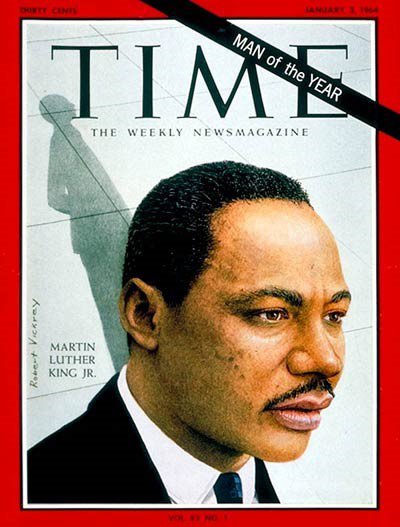

5. The Speech Immediately Changed King’s Life

Scholars, journalists, and politicians have long discussed what the speech meant for the overall civil rights movement and what it continues to mean to people today. The immediate aftereffect for King is that it launched him into the stratosphere of political leadership in America. Not that he hadn’t already made an enormous reputation for himself, but in the time that followed, King became Time’s Man of the Year for 1963 and the youngest person awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964. Though his life was unfortunately ended less than five years after delivering the speech, his legacy has proven immortal. The man is gone, but his dream lives.

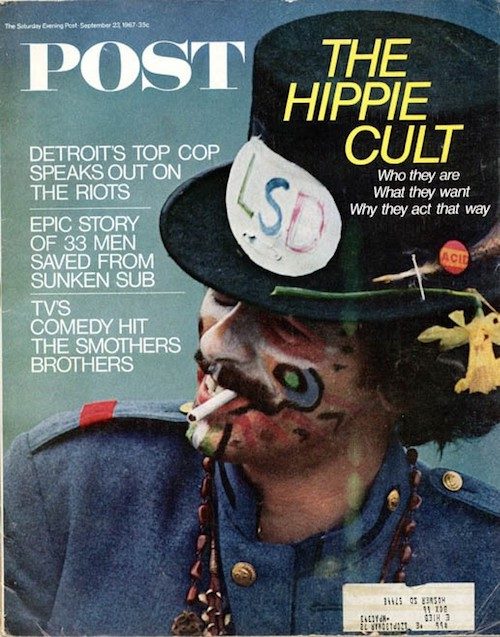

North Country Girl: Chapter 20 — The 60s Arrive in Duluth

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

In 1967, my eighth grade summer, the sixties finally trickled up to northern Minnesota. Up till then, we had existed in our own little insulated pocket of intact families, nosy neighbors, regular church-going, casual drunkenness, and a sincere belief in the virtue of conformity. Children were seen but not heard, teens were just big kids waiting to become adults, God was in his heaven, and all was right with the world.

Somewhere in the South people were marching for civil rights. Duluth had virtually no black people. We had a few grizzled Indians hanging around the liquor stores, waiting to buy booze for teen-agers in exchange for a few bucks or a can of beer. We had a handful of Jewish families, who were regarded suspiciously by my mother, although she had jumped at the chance to dump her two youngest kids in a half-day preschool at the Jewish Educational Center, where Lani, and later Heidi, learned to play the dreidel and build Sukkot tents.

Men were burning their draft cards in Berkeley and New York City; Walter Cronkite led off the news with stories of the war in Vietnam. But the college deferment was still in place, which meant that no boys who grew up in my neighborhood were at risk of being shot at by those awful Viet Cong.

Teen culture had started to seep in with the Beach Boys. But the California world of surfing and woodies seemed as exotic to us as an Indonesian dance troupe on Ed Sullivan. Our one and only radio station, WEBC (AM of course), played Top 40 music in an indiscriminate scramble: on a 15-minute drive to the store, we would hear “Ballad of the Green Berets,” “Monday, Monday,” and “Born Free.” When the Rolling Stones’ “Let’s Spend the Night Together” came out, WEBC beeped out the title line every time, in the interest of public morality.

But cracks were opening up. Time and The Saturday Evening Post, which arrived weekly at our house, increased their coverage of civil rights and anti-war protests, and I began to tilt left. The TV shows Hullabaloo and Shindig! moved away from Petula Clark and Bobby Darrin and towards the Doors (sex!) and Jefferson Airplane (drugs!).

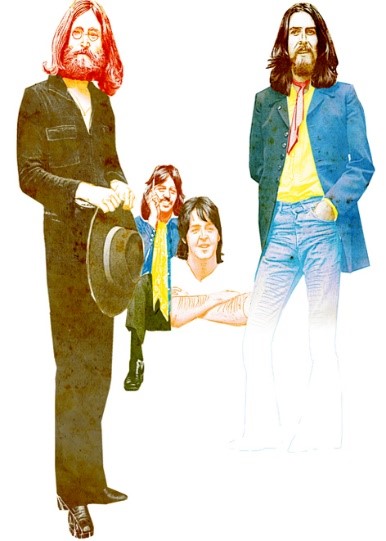

Drug culture took longer to reach us, too damn long as far as I was concerned. I had never succumbed to Beatlemania; the unwashed, sneering Rolling Stores were much more exciting. But it was mandatory that if you were between the ages of 13 and 21, you went gaga over the release of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. I happily joined in, hoping that by listening to “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” I could get an aural contact high.

Somewhere, out in the real world, people were smoking marijuana and banana peels, ingesting morning glory seeds and LSD, expanding their consciousness in all kind of ways. But I was in a basement in International Falls, sitting around a tinny hi-fi system, with Sgt. Pepper on repeat and repeat, the record coming to a scratchy end and then flipped over, while the boy who lived there was dissolving Bayer aspirin in bottles of Coca-Cola, in an attempt to get himself and his pals, which included me but not my disapproving best friend, Wendy, high. We all claimed to feel something, although what I mostly felt was sick to my stomach.

I was huddled on that basement floor because that summer I was a long-term guest at Wendy’s grandma’s house. I had outgrown camp and the Northland Country Club pool. After the mandatory visit to Aberdeen, where I spent two weeks reading and sulking, my mother gratefully sent me north and out of her hair. International Falls was a small town, a lot like Aberdeen, but smellier, thanks to the paper mill. Wendy and I were regarded as sophisticated big city girls — “Wow, you live in Duluth!” —and welcomed everywhere. The day after the aspirin experiment, we were invited to a taffy pull at a neighbor’s, something I thought existed only in the pages of a Laura Ingalls Wilder book. My hands were buttered to the wrist, as if I were to be part of an adolescent orgy. The taffy was white and ropy and smelled of vanilla, and when finished was tooth-achingly sweet and tooth-shatteringly brittle. My father would have been horrified. I was annoyed at this wholesome party activity; I wanted to be back down in that basement, listening to records with boys and figuring out ways to get high.

I also participated in a bizarre experiment in reversing Down Syndrome. Wendy’s best friend before me had a baby sister with Down’s. I didn’t quite understand what was going on with this big-headed kid who couldn’t talk. The mom, searching for a cure, had fallen under the influence of a crack-pot theory that held that crawling was the basis of all subsequent learning. The mom spent hours manipulating her baby’s arms and legs in a swimming/crawling motion. When she got too tired she recruited anyone within shouting distance to take her place. I have no idea whether it helped or not. It was horribly creepy, moving the baby’s right arm and left leg for ten minutes, then switching to the left arm and right leg, while the kid made noises somewhere between a chortle and a howl. I hated going over to that house of sadness and madness.

The kid with the basement and the aspirin and the Sgt. Pepper’s album was International Fall’s leading Bad Boy. Wendy and I adored him. Several weeks into my visit, all of us 13-year-old aspiring juvenile delinquents were hanging out on a street corner, trying to be much cooler than we actually were. Bad Boy was smoking a cigarette (oooh!) and started lighting matches and tossing them into a red and blue mailbox. Of course, we found this, as everything Bad Boy did, hysterical. At about the twentieth match, smoke began seeping through the mailbox slot. All of us stood gazing horrified as the wisp became a serious plume, a “Yeah something is really burning” smoke signal. One of Bad Boy’s friends helpfully noted that we had probably committed a federal crime, setting the U.S. mail on fire. As the smoke darkened and streamed out of the mailbox, we fled in all four directions. Wendy and I bamboozled her poor grandma with some story about why we had to be back in Duluth immediately, and pooled our money for bus tickets, hoping to stay one step ahead of the law.

***

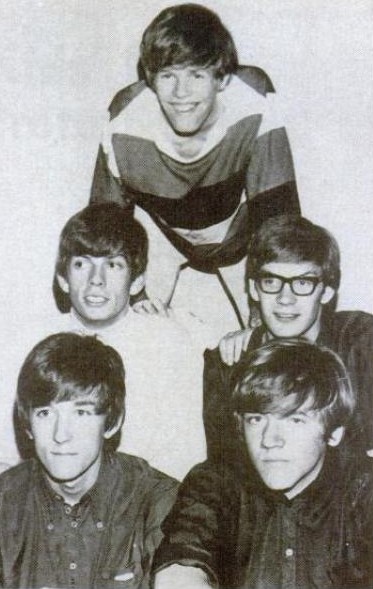

I got back to Duluth to find the entire teen universe abuzz. The Duluth auditorium, which had opened in 1966 and been home to hockey games, Ice Capades, and the Ringling Brothers Circus, was to have its first rock concert: Herman’s Hermits.

Wendy and I were speechless with joy. While Herman, aka Peter Noone, the lead singer, was almost a little too preciously adorable for my tastes (always a smile, never a sneer), he was undeniably cute. And I, like everyone under 25 in the country, had fallen under the perky, head-bobbing spell of “I’m Henry the Eighth, I Am,” which was played by the radio station at least once every hour, causing pre-teen girls to squeal, hop on one foot, and shout out “Second verse, same as the first!”

For weeks before the concert, I was lost in a whirl of daydreams where Peter Noone looked out in the audience, saw my adoring face, and fell madly in love. He would send someone out to escort me backstage, take me in his arms, kiss me, gently remove my clothes…and then stuff would happen that I was still having a difficult time imagining. I would get to that crucial point, sigh, and rewind my daydream back to the beginning.

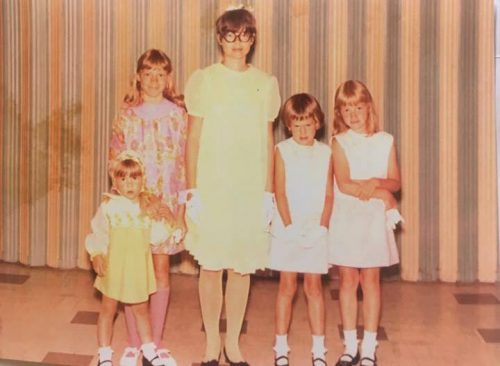

There was only one problem. I wore glasses, thick, hideous glasses which could kill the sex drive of any boy at ten paces. I could go to the concert without wearing my brown cat’s eye with sparkles (an improvement over the baby blue ones I had worn for years) but then I wouldn’t be able to see a thing onstage. How could I catch Peter Noone’s eye if he were just a fuzzy object? I wouldn’t even be able to tell him from the lesser, unnamed Hermits.

Shindig!, the TV music show, saved me. It was on during a school night, so Wendy and I had to watch it at our own homes, one ear glued to the phone, discussing which bands and boys we liked. Shindig! had a troupe of cute girl dancers (now there was a career!). One of these dancers wore, along with her mini skirts, Mondrian-inspired dresses, and go-go boots, a pair of perfectly round tortoise shell glasses. Thanks to some mysterious seismic movement or an alignment of the stars, a pair of those exact glasses showed up at my eye doctor’s, where before my choice had been between the baby blue or shit brown cat’s eyes with sparkles. My mother, the slave to fashion, was always delighted when I paid attention to what I wore and how I looked — which was still, with my badly cut mousy blonde hair, not good. But at least with my outrageously stylish new glasses, I commanded some attention from boys, most of it a startled reaction of “Weird.”

With my Shindig glasses and my own Mondrian color block mini dress, I was ready for Peter Noone to sweep me off my feet. I don’t remember what Wendy was wearing. It didn’t matter, she was only there to report back to all of Woodland Junior High that I was not in ninth grade because I had eloped with Herman.

My dad, who had been known to whistle “Henry the Eighth” himself occasionally, scored us seats a few rows from the stage. We had to sit through an opening act before Herman’s Hermits came on. That band was The Who. I had heard “I Can See for Miles” on WEBC a few times the winter before, enjoyed it, but relegated The Who to the category of British Bands I Kinda Liked: The Kinks, The Animals, The Zombies.

Seeing The Who live rocked my little Duluthian world. There I was, nicely dressed, waiting to see that sweet young man who politely told Mrs. Brown she had a lovely daughter. I got Roger Daltrey’s unhinged vocals (ooh, he was really cute!), Keith Moon’s spastic flailing over his drums, and Pete Townsend smashing his guitar on the stage floor over and over (and John Entwhistle noodling about in the background). The Who killed off any residual Minnesota nice girl in me and I was pitched head first into full-fledged Youth in Revolt. At the end of “I Can See for Miles” Townsend stomped offstage with the splintered neck of his guitar in hand while everyone around me politely applauded while muttering “Were they on drugs? What was that all about?” I knew what it was about, it was about smashing the old to make way for something completely new, whether the world or Duluth or Woodland Junior High was ready for it or not.

The crowd stood and roared when Herman’s Hermits took the stage; I was still in a daze; sorry Peter Noone, you are no longer my type.

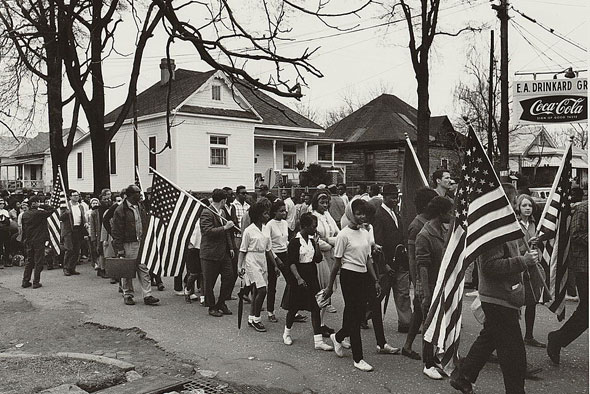

Selma and the Fight to Vote

(Image courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Last year marked a new low for voter participation in a national election. Normally, less than half of America’s voters cast ballots in the midterm elections, but the 2014 turnout was the lowest in 73 years: 36 percent. It would seem that most Americans believe their right to vote isn’t worth the effort to exercise it.

We’ve come a long way in 50 years, when Americans were ready to die just to get their names on the voter rolls — and others were willing to kill to deny them that right.

In the early 1960s, civil rights advocates traveled through the Southern states to encourage African Americans to vote. They believed the ballot would give people the power to throw out racist government officials and elect leaders who would end discrimination.

But they soon discovered that office-holders across the country had installed a number of obstacles to prevent black people from reaching the polling booths. The obstacles proved especially effective in Selma, Alabama, where only 2 percent of black residents were registered to vote.

In March 1965, activists announced they would march from Selma to Montgomery, the state capitol, and demand the state government end voter suppression. They had little hope that Governor George Wallace would change the state’s racist policy, but they knew the national attention from the march would pressure him to respond.

When marchers sets off on Sunday, March 7, the country saw how firmly some white officials opposed voting rights for black people. Sheriff’s deputies fired tear gas into the crowd, then attacked the marchers with whips and clubs. Fifty marchers were hospitalized. The marchers set out again on March 21, led by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and with protection from the National Guard and U.S. Army sent by President Johnson.

On the second day, the marchers passed through Trickem Fork, an impoverished hamlet in Lowndes County, Alabama, that represented much of what the protestors were trying to change. The Saturday Evening Post reporters W. C. Heinz and Bard Lindeman noted, “The Negroes outnumber the whites almost four to one, but until the week before the Freedom March not one Negro voter had been registered in Lowndes County in 65 years.” (“The Meaning of the Selma March: Great Day at Trickem Fork,” May 22, 1965)